Pattern and Predictors of Cardiac Rhythm Disturbances in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis

Md. Saiful Ahammad Sarker1*, Asia Khanam2, Md. Fakhrul Islam Khaled3, S. M. Remin Rafi4, Afrin Akter5, Anjuman Ara Daisy5, SK Afsana Hossain5, H. M. Mohiuddin Alamgir5, Mohammad Kamrul Hasan6

1Transplant Coordinator, National Institute of Kidney Diseases & Urology, Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, Dhaka, Bangladesh 2Professor, Department of Nephrology, Bangladesh Medical University (BMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh

3Associate Professor, Department of Cardiology, Bangladesh Medical University (BMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh

4Medical Officer, Department of Nephrology, Bangladesh Medical University (BMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh

5Medical Officer, Officer on Special Duty (OSD), Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Dhaka, Bangladesh

6Assistant Professor, Department of Nephrology, Monno Medical College and Hospital, Manikganj, Bangladesh

*Corresponding Author: Md. Saiful Ahammad Sarker, Medical Officer, Upazila Health Complex (UHC), Hajiganj, Chandpur, Bangladesh.

Received: 13 August 2025; Accepted: 25 August 2025; Published: 13 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Md. Saiful Ahammad Sarker, Asia Khanam, Md. Fakhrul Islam Khaled, S. M. Remin Rafi, Afrin Akter, Anjuman Ara Daisy, SK Afsana Hossain, H. M. Mohiuddin Alamgir, Mohammad Kamrul Hasan. Pattern and Predictors of Cardiac Rhythm Disturbances in Patients on Maintenance Hemodialysis. Archives of Nephrology and Urology 8 (2025): 126-134.

DOI: 10.26502/anu.2644-2833106

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

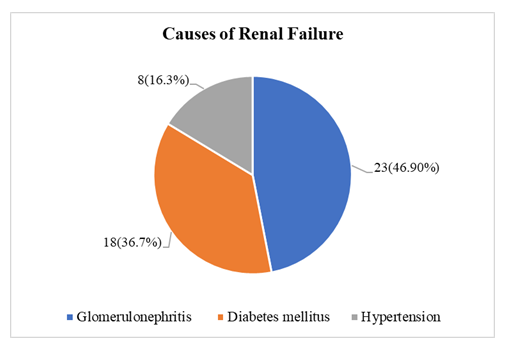

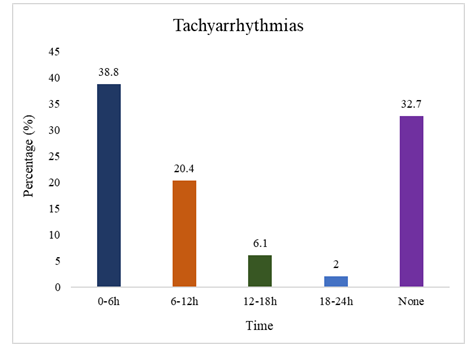

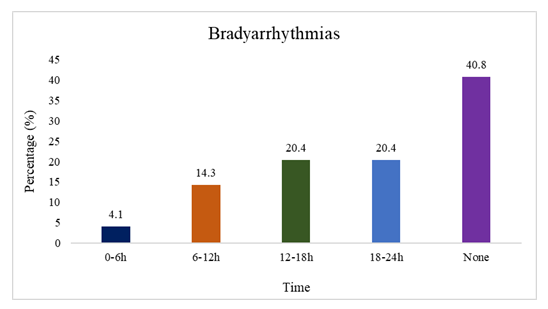

Background: Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the major cause of death among patients on maintenance hemodialysis. It is closely associated with cardiovascular and metabolic changes occurring in patients undergoing hemodialysis. Cardiac arrhythmias were frequently observed in these dialysis patients. Aim of the study: To detect the pattern and predictors of cardiac rhythm disturbances in maintenance hemodialysis patient. Methods: This cross-sectional study was conducted in the Department of Nephrology at BSMMU, Dhaka. A total of 49 patients on maintenance hemodialysis were included based on selection criteria. After inclusion, ECG & echocardiogram were performed on non-dialysis day. On dialysis day, 24-hour Holter ECG monitoring, selective pre & post dialytic laboratory investigations were carried out. The sampling method used was purposive sampling. Data were collected using a predesigned data collection sheet, including patient history and clinical examination. Statistical analyses of the results were performed using software with SPSS-26. Result: The mean age of the study cohort was 42.1 ± 12.3 years, with a predominance of male patients (73.5%). The primary etiology of renal failure was glomerulonephritis (46.9%), followed by diabetes mellitus (36.7%) and hypertension (16.3%). Echocardiographic assessment revealed a mean left ventricular mass index (LVMI) of 130.6 ± 43.7 g/m². Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) was significantly elevated in patients with tachyarrhythmia (37.7 ± 15.1 mmHg) compared to those without (29.4 ± 13.3 mmHg, p<0.05). Supraventricular arrhythmias were frequent, with premature atrial contractions (PACs) observed in 77.6% of patients; PAC burden averaged 2.49 ± 8.60 per hour, and 8.2% had >70 PACs/day. Ventricular arrhythmias, predominantly premature ventricular contractions (PVCs), occurred in 71.4%, with a mean rate of 0.61 ± 1.22 per hour; 5.7% exhibited a PVC burden between 5–10%. Bradyarrhythmias and tachyarrhythmias were present in 59.2% and 65.3% of patients, respectively. Logistic regression identified significant associations of PACs with post-dialysis magnesium levels, and PVCs with post-dialysis potassium, magnesium, LVMI, and PASP. No correlation was found between arrhythmias and dialysis access type or frequency. Conclusion: Arrhythmias including significant abnormal rhythms, were common but their burden was less. Tachyarrhythmias occurred more often during and immediately after dialysis where bradyarrhythmias were less prevalent in initial period & increased with time. Further study is needed to determine their impact on clinical outcomes.

Keywords

<p>Cardiac rhythm disturbances, Maintenance hemodialysis, Chronic Kidney Disease Stage 5 (CKD-5), Arrhythmias, Holter monitoring</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is a global public health concern characterized by a progressive decline in renal function, defined by structural or functional kidney abnormalities persisting for over three months [1]. As CKD advances, it often culminates in End-Stage Renal Disease (ESRD), necessitating Renal Replacement Therapy (RRT) for patient survival [2]. Among the modalities of RRT, hemodialysis (HD) remains a cornerstone treatment, facilitating the removal of excess fluid, metabolic waste, and toxins from the bloodstream using an extracorporeal circuit [3]. Despite its life-sustaining benefits, HD is strongly associated with significant cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) remains the leading cause of death in ESRD patients, accounting for over 50% of all deaths according to the 2016 US Renal Data System (USRDS) report [4]. Notably, sudden cardiac death (SCD), often due to arrhythmias, contributes to nearly 37% of these fatalities. The mortality rate among patients undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) for more than three months is 10–15 times higher than that of the age- and sex-matched general population [5]. Ventricular arrhythmias are particularly prevalent and are considered a major risk factor for SCD in this population [6,7]. Studies utilizing 24-hour Holter monitoring have shown that ventricular arrhythmias affect 13% to 50% of HD patients [7]. These arrhythmias are frequently linked with structural heart disease, such as left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH), left ventricular (LV) systolic and diastolic dysfunction, and vascular calcification [8]. Moreover, atrial fibrillation (AF), another common arrhythmia in ESRD, affects 13% to 23.4% of patients on HD and is associated with a heightened risk of thromboembolic events, including stroke [9]. Cardiac arrhythmias in CKD patients arise from a complex interplay of arrhythmogenic substrates, triggering factors, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction [10]. Electrocardiography and echocardiography play pivotal roles in identifying structural abnormalities, while heart rate variability (HRV) offers insights into autonomic regulation. Reduced HRV, indicative of autonomic dysfunction, has been linked with ventricular arrhythmia and increased SCD risk in HD patients [11]. LVH, a prevalent complication in CKD, results from volume overload, hypertension, sympathetic overactivity, and renin-angiotensin system activation [12]. Non-hemodynamic contributors include anemia, mineral bone disorders, inflammation, and dysregulated calcium-phosphorus metabolism, all of which promote myocardial fibrosis and dysfunction [13]. Similarly, systolic dysfunction and reduced ejection fraction predispose patients to arrhythmias via sympathetic neurohumoral activation [14]. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), seen in up to one-third of MHD patients, also correlates with arrhythmic events in about 16% of cases [15]. Furthermore, electrolyte imbalances—such as hyperkalemia, hypocalcemia, and hyperphosphatemia—are common in ESRD and contribute to the development of fatal arrhythmias [16]. Hemodialysis procedures themselves can provoke arrhythmogenic events, particularly AF [17]. However, data on the patterns and predictors of cardiac arrhythmias in HD patients in Bangladesh remain sparse. This study aims to explore the prevalence, types, and associated factors of cardiac rhythm disturbances among MHD patients in Bangladesh, thereby contributing valuable insights for risk stratification, monitoring, and preventive strategies in this high-risk population.

2. Methodology and Materials

This cross-sectional observational study was conducted at the Department of Nephrology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University (BSMMU), and Dhaka, Bangladesh. The study was carried out over a period of 18 months, from April 2023 to September 2024. Participants were recruited from both the inpatient and outpatient hemodialysis (HD) units under the Department of Nephrology.

2.1 Study Population

The study included adult patients (≥18 years) with end-stage renal disease (CKD Stage 5) undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (MHD) for a minimum duration of 3 months. Purposive sampling was employed. A total of 50 patients were enrolled, of which one patient was excluded due to incomplete Holter ECG data, resulting in a final analyzed cohort of 49 patients.

2.2 Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

- • Age ≥ 18 years

- • On maintenance hemodialysis for ≥ 3 months

Exclusion Criteria

- • Structural or congenital heart disease

- • Known arrhythmia or previous diagnosis of paroxysmal atrial fibrillation, WPW syndrome, Brugada syndrome, or long QT syndrome

- • Ischemic heart disease or history of sudden cardiac arrest

- • Thyroid dysfunction, COPD, bronchial asthma

- • Use of arrhythmogenic drugs (e.g., salbutamol, theophylline, amphetamine, caffeine, alcohol)

2.3 Data Collection Procedure

After obtaining ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of BSMMU and informed written consent from participants, detailed demographic, clinical, dialysis-related, echocardiographic, and laboratory data were collected using a structured data collection form. Information included age, sex, BMI, smoking history, comorbidities (diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia), and current medications (e.g., β-blockers, CCBs, α-blockers). Dialysis data encompassed frequency, duration, interdialytic weight gain, and access type. All patients received standard bicarbonate dialysis using synthetic dialyzers (Fresenius 4008, dialyzer size 1.6–1.8 m², blood flow rate 200–400 mL/min, dialysate flow 500 mL/min).

2.4 Laboratory and Echocardiographic Evaluation

Venous blood samples were drawn before and after dialysis for hematologic and biochemical analysis, including hemoglobin, electrolytes, albumin, calcium, magnesium, phosphate, bicarbonate (TCO2), and intact parathyroid hormone (iPTH). Laboratory analyses were performed in respective departments at BSMMU using standard techniques and reagents. Transthoracic echocardiography was conducted on interdialytic days using GE Vivid E9 equipment. Parameters assessed included left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF, Teicholz method), left ventricular mass index (LVMI), left ventricular internal diameter (LVIDD), and pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP, Bernoulli equation).

2.5 Holter ECG Monitoring

All patients underwent continuous 24-hour Holter ECG monitoring using the DMS 300–4A recorder. Monitoring began just prior to the dialysis session and continued throughout the day and night. Patients were instructed to maintain regular activities while avoiding showers. Data were extracted and analyzed by a cardiologist blinded to clinical and laboratory information. Arrhythmia types, burden, and patterns—including PACs, PVCs, bradyarrhythmias, and tachyarrhythmias—were recorded and quantified.

2.6 Statistical Analysis

All data were entered, verified, and analyzed using IBM SPSS version 26. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables were presented as frequencies and percentages. Comparisons between groups were performed using unpaired or paired t-tests as appropriate. Chi-square tests were used for categorical associations. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent predictors of specific arrhythmia types. A two-tailed p-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

2.7 Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) for human research ethics. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of BSMMU. Informed consent was obtained in both English and Bangla from each participant. Confidentiality of data was maintained throughout, and participation was voluntary with full rights to withdraw at any time without consequences. No financial compensation was provided, and there was no conflict of interest.

3. Result

The study population had a mean age of 42.1 ± 12.3 years, with 53.06% over 40 and a male predominance (73.47%). The average weight was 63.0 ± 11.3 kg and BMI 23.6 ± 4.8 kg/m², with most patients having normal BMI. Hypertension was the most common comorbidity (95.92%), followed by diabetes (36.73%) and dyslipidemia (12.24%). Most patients were on DHP-CCBs (75.51%), β-blockers (67.35%), and α-blockers (32.65%). Only 4.08% reported current smoking (Table 1). The average dialysis duration was 15.6 ± 14.4 months. 79.59% underwent two hemodialysis sessions per week. The predominant vascular access was an arteriovenous fistula, used by 91.84% of patients, with only 8.16% relying on a permanent catheter. On dialysis days, the average session duration was consistently 4 hours. The mean ultrafiltration volume was 2.34 ± 0.92 liters, and the average interdialytic weight gain was 2.39 ± 0.95 kg. 82.4 ± 7.13 beats per minute was the mean pulse rate, whereas 143.7 ± 16.1 mmHg and 84.8 ± 11.1 mmHg were the mean systolic and diastolic blood pressures, respectively (Table 2). The most common cause of renal failure in the study population was glomerulonephritis (46.9%), followed by diabetes mellitus (36.7%) and hypertension (16.3%) (Figure 1). Among all hemodialysis patients, 95.92% had preserved ejection fraction (mean LVEF 60.5 ± 5.5%), while 4.08% had reduced EF. The mean LVMI was 130.6 ± 43.7 g/m² and LVIDD was 52.2 ± 5.16 mm. Diastolic dysfunction was observed in 28.57% of cases, mostly Grade 1. Aortic sclerosis was found in 8.16%, and the mean PASP was 32.3 ± 14.3 mmHg (Table 3). While sodium levels remained unchanged (137.4 mmol/L; p=1.0), significant reductions were seen in potassium (4.67 ± 0.64 to 4.16 ± 0.55 mmol/L; p<0.001), inorganic phosphate (4.51 ± 1.09 to 4.14 ± 1.07 mg/dL; p=0.014), and magnesium (non-significant). Bicarbonate (TCO2) increased significantly post-dialysis (20.53 ± 3.39 to 25.45 ± 2.68 mmol/L; p=0.001), along with calcium (8.85 ± 1.15 to 9.28 ± 1.73 mg/dL; p=0.023) (Table 4). Holter monitoring showed a high incidence of arrhythmias, with PACs in 77.55% and PVCs in 71.43% of patients. Bradyarrhythmia was seen in 59.18%, and tachyarrhythmia in 65.31% (Table 5). Tachyarrhythmias were most frequently observed within the first 0–6 hours (38.8%). Incidences declined sharply thereafter, with 6.1% between 12–18 hours, and only 2% between 18–24 hours. No tachyarrhythmias were detected in 32.7% of patients (Figure 2). Figure 3 shows that Bradyarrhythmias were most commonly observed during 12–18 hours and 18–24 hours (each 20.4%). A smaller portion (4.1%) occurred during 0–6 hours, while 40.8% of patients exhibited no bradyarrhythmias during the monitoring period. Logistic regression analysis revealed that lower post-dialysis magnesium levels were significantly associated with premature atrial contractions (PACs) (p=0.004). Low post-dialysis potassium (p=0.033) and magnesium (p=0.039), along with higher LVMI (p=0.008) and PASP (p=0.026), were significant predictors of premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). Diabetes mellitus showed a protective effect against bradyarrhythmia (p=0.028), and higher PASP was significantly associated with tachyarrhythmia (p=0.042) (Table 6). Comparison between patients with and without tachyarrhythmia showed that those with arrhythmia had significantly higher PASP (37.7 ± 15.1 vs. 29.4 ± 13.3 mmHg; p=0.042) and lower ejection fraction (59.3 ± 5.4% vs. 62.6 ± 5.2%; p=0.044). No significant differences were observed in demographic, comorbidity, or dialysis access and frequency variables (Table 7). Β-blocker use was significantly associated with a lower overall arrhythmia rate (p=0.018) and specifically with fewer PVCs (p=0.021), though no significant associations were found with PACs, tachyarrhythmia, or bradycardia (Table 8).

Table 1: Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study population (N = 49).

|

Variable |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Age group (years) |

||

|

<40 |

23 |

46.94 |

|

>40 |

26 |

53.06 |

|

Mean ±SD |

42.1±12.3 |

|

|

Gender |

||

|

Male |

36 |

73.47 |

|

Female |

13 |

26.53 |

|

Weight (kg) |

||

|

Mean ±SD |

63.0±11.3 |

|

|

BMI (kg/m2) |

||

|

Underweight (<18.5) |

5 |

10.20 |

|

Normal (18.5- 24.9) |

31 |

63.27 |

|

Overweight (25- 29.9) |

11 |

22.45 |

|

Obese (>30) |

2 |

4.08 |

|

Mean ±SD |

23.6±4.8 |

|

|

Current smoking |

2 |

4.08 |

|

Comorbidities |

||

|

Diabetes mellitus |

18 |

36.73 |

|

Hypertension |

47 |

95.92 |

|

Dyslipidemia |

6 |

12.24 |

|

Antihypertensive medication |

||

|

DHP-CCB |

37 |

75.51 |

|

β-blocker |

33 |

67.35 |

|

α-blocker |

16 |

32.65 |

Table 2: Hemodialysis parameters and On-Dialysis physiological parameters in the study cohort (N = 49).

|

Dialysis variables |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Dialysis Duration (months) (mean ±SD) |

15.6 ± 14.4 |

|

|

HD Sessions per Week |

||

|

2 |

39 |

79.59 |

|

3 |

10 |

20.41 |

|

HD Access Type |

||

|

Arteriovenous Fistula |

45 |

91.84 |

|

Permanent Catheter |

4 |

8.16 |

|

Measurement on Dialysis Day (mean ±SD) |

||

|

Dialysis Duration (hours) |

4.0 ± 0.0 |

|

|

Ultrafiltration (L) |

2.34 ± 0.92 |

|

|

Interdialytic Weight Gain (Kg) |

2.39 ± 0.95 |

|

|

Pulse (beats/min) |

82.4 ± 7.13 |

|

|

Systolic BP (mmHg) |

143.7 ± 16.1 |

|

|

Diastolic BP (mmHg) |

84.8 ± 11.1 |

|

Table 3: Comprehensive echocardiographic findings in patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis (N = 49).

|

Echocardiographic findings |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Ejection fraction |

||

|

<50% |

2 |

4.08 |

|

>50% |

47 |

95.92 |

|

Mean±SD |

60.5±5.5 |

|

|

LVMI (g/m2) |

130.6±43.7 |

|

|

LVIDD (mm) |

52.2±5.16 |

|

|

Diastolic dysfunction |

||

|

Grade 1 |

8 |

16.33 |

|

Grade 2 |

3 |

6.12 |

|

Grade 3 |

1 |

2.04 |

|

Aortic sclerosis |

4 |

8.16 |

|

PASP (mmHg) |

32.3±14.3 |

|

Table 4: Pre- and post-dialysis laboratory measurements and biochemical changes (N=49).

|

Parameter |

Before Dialysis |

After Dialysis |

p-value |

|

Hemoglobin (g/dL) |

10.0 ± 1.23 |

- |

- |

|

Sodium (mmol/L) |

137.4 ± 3.65 |

137.4 ± 3.28 |

1 |

|

Potassium (mmol/L) |

4.67 ± 0.64 |

4.16 ± 0.55 |

<0.001* |

|

TCO2 (mmol/L) |

20.53 ± 3.39 |

25.45 ± 2.68 |

0.001* |

|

Calcium (mg/dL) |

8.85 ± 1.15 |

9.28 ± 1.73 |

0.023* |

|

Magnesium (mg/dL) |

2.55 ± 2.77 |

2.25 ± 0.54 |

0.49 |

|

Inorganic Phosphate (mg/dL) |

4.51 ± 1.09 |

4.14 ± 1.07 |

0.014* |

|

Albumin (g/L) |

35.8 ± 6.01 |

35.60 ± 6.19 |

0.798 |

|

PTH (pg/mL) |

294.6 ± 212.8 |

- |

- |

Table 5: Distribution and characteristics of arrhythmias detected by 24-hour Holter monitoring.

|

Variable |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Holter Monitoring Parameters (Mean ± SD) |

||

|

Duration of recording (hours) |

22.9 ± 2.01 |

|

|

Mean heart rate (beats/min) |

78.1 ± 11.21 |

|

|

Supraventricular Arrhythmias |

||

|

Patients with PACs |

38 |

77.55 |

|

PACs (total count) |

58.8 ± 167.0 |

|

|

PACs per hour |

2.49 ± 8.60 |

|

|

PACs <70 per day |

34 |

89.47 |

|

PACs >70 per day |

4 |

10.53 |

|

Ventricular Arrhythmias |

||

|

Patients with PVCs |

35 |

71.43 |

|

PVCs (total count) |

18.6 ± 27.4 |

|

|

PVCs per hour |

0.61 ± 1.22 |

|

|

PVCs <5% of total beats |

33 |

94.29 |

|

PVCs 5-10% of total beats |

2 |

5.71 |

|

Bradyarrhythmias |

||

|

Patients with sinus bradycardia (<60 bpm) |

29 |

59.18 |

|

Tachyarrhythmias |

||

|

Patients with tachyarrhythmia (>100 bpm) |

32 |

65.31 |

Table 6: Logistic regression analysis of predictors of premature atrial and ventricular contractions, bradycardia, and tachyarrhythmia.

|

Arrhythmia Type |

Predictor Variable |

OR (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

PACs |

Age > 40 years |

0.416 (0.104–14.66) |

0.208 |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

3.27 (0.62–17.20) |

0.147 |

|

|

Hypertension |

3.70 (0.212–64.50) |

0.34 |

|

|

Potassium (post-dialysis) |

0.150 (0.01–2.11) |

0.159 |

|

|

Calcium (post-dialysis) |

0.854 (0.41–1.76) |

0.671 |

|

|

Magnesium (post-dialysis) |

0.000 (0.000–0.031) |

0.004* |

|

|

Bicarbonate (TCO2) |

0.869 (0.62–1.22) |

0.423 |

|

|

Ejection Fraction (%) |

1.03 (0.89–1.17) |

0.712 |

|

|

LVMI (g/m²) |

0.989 (0.97–1.01) |

0.269 |

|

|

PASP (mmHg) |

0.992 (0.94–1.05) |

0.784 |

|

|

PVCs |

Age > 40 years |

0.370 (0.102–1.34) |

0.124 |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

1.67 (0.44–6.38) |

0.453 |

|

|

Hypertension |

2.62 (0.15–44.90) |

0.493 |

|

|

Potassium (post-dialysis) |

0.110 (0.01–0.84) |

0.033* |

|

|

Calcium (post-dialysis) |

0.498 (0.25–1.00) |

0.051 |

|

|

Magnesium (post-dialysis) |

0.007 (0.000–0.772) |

0.039* |

|

|

Bicarbonate (TCO2) |

0.920 (0.71–1.20) |

0.538 |

|

|

Ejection Fraction (%) |

1.01 (0.87–1.17) |

0.933 |

|

|

LVMI (g/m²) |

1.15 (0.91–2.99) |

0.008* |

|

|

PASP (mmHg) |

1.103 (0.83–1.99) |

0.026* |

|

|

Bradyarrhythmias |

Age > 40 years |

1.61 (0.51–5.09) |

0.419 |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

0.260 (0.07–0.886) |

0.028* |

|

|

Tachyarrhythmias |

Age > 40 years |

1.43 (0.43–4.69) |

0.556 |

|

Diabetes Mellitus |

0.75 (0.22–2.51) |

0.638 |

|

|

PASP (mmHg) (comparison group) |

– |

0.042* |

Table 7: Association of tachyarrhythmia with clinical and echocardiographic parameters in MHD patients (N = 49).

|

Variable |

With Arrhythmia(n = 32) |

Without Arrhythmia(n = 17) |

p-value |

|

Demographics & Comorbidities |

|||

|

Age (years), Mean ± SD |

40.8 ± 12.5 |

44.6 ± 11.8 |

0.300 ‡ |

|

Male sex |

23 (71.88) |

13 (76.47) |

0.729 † |

|

Diabetes mellitus |

11 (34.38) |

7 (41.18) |

0.638 † |

|

Hypertension |

30 (93.75) |

17 (100.00) |

0.293 † |

|

Echocardiographic Parameters |

|||

|

LVMI (g/m²), Mean ± SD |

126.8 ± 44.4 |

134.1 ± 48.4 |

0.601 ‡ |

|

PASP (mmHg), Mean ± SD |

37.7 ± 15.1 |

29.4 ± 13.3 |

0.042* ‡ |

|

Ejection Fraction (%), Mean ± SD |

59.3 ± 5.4 |

62.6 ± 5.2 |

0.044* ‡ |

|

Hemodialysis Parameters |

With Arrhythmia(n = 42) |

Without Arrhythmia(n = 7) |

p-value |

|

HD Access: AV Fistula |

39 (92.86) |

6 (85.71) |

0.523 † |

|

HD Access: Perm. Catheter |

3 (7.14) |

1 (14.29) |

|

|

HD Frequency: 2/week |

33 (78.57) |

6 (85.71) |

0.664 † |

|

HD Frequency: 3/week |

9 (21.43) |

1 (14.29) |

|

Table 8: Association between β-blocker use and occurrence of arrhythmias and bradycardia in the study population.

|

Variables |

β-Blocker |

p-value |

|

|

Yes |

No |

||

|

Any Arrhythmia (n = 42) |

31 (73.81) |

11 (26.19) |

0.018* |

|

PAC (n = 38) |

27 (71.05) |

11 (28.95) |

0.304 |

|

PVC (n = 35) |

27 (77.14) |

8(22.86) |

0.021* |

|

Tachyarrhythmia (n = 32) |

22 (68.75) |

10 (31.25) |

0.774 |

|

Bradycardia (n = 29) |

21 (72.41) |

8 (27.59) |

0.362 |

4. Discussion

Cardiac rhythm disturbances are a major cause of morbidity and mortality among patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) undergoing maintenance hemodialysis (MHD). These disturbances are driven by complex interactions among electrolyte imbalances, fluid overload, uremic toxins, and cardiac structural abnormalities. As these arrhythmias often remain asymptomatic, early identification and assessment of predictive factors are crucial for improving outcomes in this vulnerable population [18]. This study evaluated 49 patients on MHD and found a mean age of 42.1±12.3 years, with 53.06% being older than 40. This aligns with evidence suggesting that advancing age is linked to increased cardiovascular risk due to prolonged exposure to hypertension, diabetes, and uremia [19]. A male predominance (73.47%) was observed, in line with global trends indicating a higher burden of CKD progression in males [20]. Most patients had a normal BMI (mean 23.6±4.8 kg/m²), but 10.2% were underweight and 26.5% were overweight or obese. Although BMI was within acceptable limits for the majority, CKD-related metabolic alterations may still predispose patients to arrhythmias [21]. Only 4.08% of patients were current smokers, which may reflect sociocultural factors or successful public health interventions in Bangladesh [22]. Hypertension was the most prevalent comorbidity (95.92%), underscoring its etiological and pathophysiological role in CKD and its complications [23]. Diabetes mellitus was present in 36.73% of patients, while dyslipidemia was noted in 12.24%, possibly reflecting local dietary habits [24]. Antihypertensive usage was high, with 75.51% of patients on dihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (DHP-CCBs), 67.35% on β-blockers, and 32.65% on α-blockers, consistent with treatment practices for CKD-associated hypertension and cardiovascular protection [30]. Patients had been on dialysis for a mean of 15.6±14.4 months, with the majority (79.59%) receiving dialysis twice weekly, suggesting resource limitations compared to international recommendations. Arteriovenous fistula (AVF) was the access of choice in 91.84% of patients, favoring long-term dialysis outcomes [26]. On dialysis days, patients experienced a mean ultrafiltration volume of 2.34±0.92 L and interdialytic weight gain of 2.39±0.95 kg. Blood pressure readings remained elevated (143.7±16.1 / 84.8±11.1 mmHg), indicating residual fluid overload [27]. Echocardiographic assessment revealed preserved ejection fraction in 95.92% (mean EF: 60.5±5.5%), but structural abnormalities were prevalent. The mean left ventricular mass index (LVMI) was 130.6±43.7 g/m², and LVIDD averaged 52.2±5.16 mm. Diastolic dysfunction was present in 24.5% (Grade 1 in 16.3%, Grade 2 in 6.1%, Grade 3 in 2%). Pulmonary artery systolic pressure (PASP) was elevated at 32.3±14.3 mmHg, reflecting increased cardiovascular strain and pulmonary hypertension risk [15]. Dialysis significantly improved several biochemical markers. Potassium levels declined from 4.67±0.64 to 4.16±0.55 mmol/L (p < 0.001), while TCO2 rose from 20.53±3.39 to 25.45±2.68 mmol/L (p = 0.001), indicating effective electrolyte and acid-base regulation. Calcium increased (p = 0.023), and phosphate decreased significantly (p = 0.014). Serum magnesium decreased slightly but nonsignificantly (p = 0.49); however, post-dialysis magnesium was a significant predictor of PACs and PVCs, supporting its arrhythmia-protective role [31]. Holter monitoring identified a high prevalence of arrhythmias. PACs were observed in 77.55% of patients, with 10.53% exceeding 70 PACs/day. PVCs were present in 71.43%, though 94.29% had a burden <5% of total beats. Sinus bradycardia was found in 59.18%, and tachyarrhythmias in 65.31%, often occurring within the first six hours post-dialysis, suggesting a strong physiological trigger related to the dialysis procedure [35]. Multivariate logistic regression showed that post-dialysis magnesium was significantly associated with both PACs (p = 0.004) and PVCs (p = 0.039), and post-dialysis potassium was also a predictor of PVCs (p = 0.033). This underscores the importance of electrolyte stability in arrhythmia prevention [20, 31]. Increased PASP (OR = 1.103, p = 0.026) and LVMI (OR = 1.15, p = 0.008) were also significantly associated with PVCs, highlighting the contribution of structural heart changes to arrhythmogenic risk [37]. Diabetes mellitus was significantly associated with bradyarrhythmias (OR = 0.260, p = 0.028), reinforcing the role of autonomic dysfunction in diabetic patients [19]. In patients with tachyarrhythmia, PASP was significantly higher (37.7±15.1 mmHg vs. 29.4±13.3 mmHg; p = 0.042), and mean ejection fraction was significantly lower (59.3±5.4% vs. 62.6±5.2%; p = 0.044), further confirming cardiovascular remodeling as a driver of rhythm abnormalities. Beta-blocker use was significantly associated with an increased incidence of overall arrhythmias (p = 0.018) and PVCs (p = 0.021). This paradoxical finding may be related to the timing of administration relative to dialysis sessions or inadequate dosage titration, rather than a lack of efficacy [38]. No significant associations were found between arrhythmia prevalence and HD access type or frequency, suggesting that internal cardiovascular and metabolic factors may outweigh dialysis procedural aspects in arrhythmogenesis [39].

Limitations of the study:

This study has several limitations. Dialysis adequacy was not individually assessed despite using the same dialyzer and solution. A more homogeneous population receiving thrice-weekly dialysis might yield more consistent results. Holter monitoring was limited to 24 hours, potentially underestimating arrhythmia burden. The study population was relatively young, which may not reflect the typical arrhythmia-prone demographic. Additionally, strict exclusion of patients with structural heart disease, regional wall motion abnormalities, and left ventricular dysfunction likely contributed to the lower incidence of detected arrhythmias.

5. Conclusion

This study was undertaken to evaluate the pattern and factors associated with cardiac rhythm disturbances in maintenance hemodialysis patients. In conclusion, maintenance hemodialysis patients experienced a high prevalence of both supraventricular and ventricular arrhythmias but their burden was very low. Premature atrial contractions (PACs) were more common than premature ventricular contractions (PVCs). While tachyarrhythmias occurred more often during and immediately after dialysis, bradyarrhythmias were found more in post dialytic period and increased with time. Patients with rigorous clearance of post dialysis potassium & magnesium were significantly associated with PACs & PVCs. Arrhythmias also found significantly associated with increased left ventricular mass index & pulmonary arterial systolic pressure.

6. Recommendations

Routine Holter monitoring is not necessary in asymptomatic hemodialysis patients without cardiac disease. Regular monitoring of serum magnesium and timely correction may reduce arrhythmia risk. Hemodialysis can be safely conducted in most patients with standard precautions. Further longitudinal studies are needed to evaluate the protective role of β-blockers.

Funding:

No funding sources

Conflict of interest:

None declared

Ethical approval:

The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

References

- Francis A, Harhay MN, Ong AC, et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nature Reviews Nephrology 20 (2024): 473-485.

- Taiwo A. Chronic and End-Stage Renal Disease. Psychosocial Care of End-Stage Organ Disease and Transplant Patients (2018): 63.

- Nalesso F, Cacciapuoti M, Bogo M, et al. Overview, technical aspects, and safety of RRT modalities in critical care. Nutrition, Metabolism and Kidney Support: A Critical Care Approach (2024): 493-520.

- Samanta R, Chan C, Chauhan VS, et al. Arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death in end stage renal disease: epidemiology, risk factors, and management. Canadian Journal of Cardiology 35 (2019): 1228-1240.

- Bozbas H, Atar I, Yildirir A, et al. Prevalence and predictors of arrhythmia in end stage renal disease patients on hemodialysis. Renal Failure 29 (2007): 331-339.

- Genovesi S, Pogliani D, Faini A, et al. Prevalence of atrial fibrillation and associated factors in long-term hemodialysis patients. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 46 (2005): 897-902.

- Adebayo RA, Ikwu AN, Balogun MO, et al. Heart rate variability and arrhythmic patterns of 24-hour Holter electrocardiography among Nigerians with cardiovascular diseases. Vascular Health and Risk Management (2015): 353-359.

- Jameel FA, Junejo AM, ul ain Khan Q, et al. Echocardiographic changes in chronic kidney disease patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Cureus 12 (2020).

- Vázquez E, Sánchez-Perales C, Lozano C, et al. Comparison of prognostic value of atrial fibrillation versus sinus rhythm in long-term hemodialysis patients. American Journal of Cardiology 92 (2003): 868-871.

- Kiuchi MG, Ho JK, Nolde JM, et al. Sympathetic activation in hypertensive chronic kidney disease: a stimulus for cardiac arrhythmias and sudden cardiac death? Frontiers in Physiology 10 (2020): 1546.

- Kida N, Tsubakihara Y, Kida H, et al. Usefulness of measurement of heart rate variability by Holter ECG in hemodialysis patients. BMC Nephrology 18 (2017): 8.

- Arodiwe EB. Left ventricular hypertrophy in renal failure review. Nigerian Journal of Clinical Practice 10 (2007): 83-90.

- Zanib A, Anwar S, Saleem K, et al. Frequency of left ventricular hypertrophy among patients on maintenance hemodialysis. Cureus 12 (2020).

- Bleyer A, Hartman J, Brannon PC, et al. Characteristics of sudden death in hemodialysis patients. Kidney International 69 (2006): 2268-2273.

- Engole YM, Lepira FB, Nlandu YM, et al. Pulmonary arterial hypertension in maintenance hemodialysis patients: a cross-sectional study. BMC Nephrology 21 (2020): 460.

- Ganesh SK, Stack AG, Levin NW, et al. Association of elevated serum PO4, Ca × PO4 product, and parathyroid hormone with cardiac mortality in chronic hemodialysis patients. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 12 (2001): 2131-2138.

- Korantzopoulos PG, Goudevenos JA, et al. Atrial fibrillation in end-stage renal disease: an emerging problem. Kidney International 76 (2009): 247-249.

- Echefu G, Stowe I, Burka S, et al. Pathophysiological concepts and screening of cardiovascular disease in dialysis patients. Frontiers in Nephrology 3 (2023): 1198560.

- Rantanen JM, Riahi S, Schmidt EB, et al. Arrhythmias in patients on maintenance dialysis: a cross-sectional study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 75 (2020): 214-224.

- Sacher F, Jesel L, Borni-Duval C, et al. Cardiac rhythm disturbances in hemodialysis: early detection using an implantable loop recorder. JACC Clinical Electrophysiology 4 (2018): 397-408.

- Khanna D, Peltzer C, Kahar P, et al. Body mass index: a screening tool analysis. Cureus 14 (2022).

- Dai X, Gakidou E, Lopez AD, et al. Evolution of the global smoking epidemic over the past half century. Tobacco Control 31 (2022): 129-137.

- Verde E, de Prado AP, Lopez-Gomez JM, et al. Asymptomatic intradialytic supraventricular arrhythmias and outcomes in hemodialysis patients. CJASN 11 (2016): 2210-2217.

- Oliveira Bastos Bonato F, Watanabe R, Montebello Lemos M, et al. Asymptomatic ventricular arrhythmia and outcomes in chronic kidney disease: a pilot study. Cardiorenal Medicine 7 (2016): 66-73.

- Blankestijn PJ, Vernooij RW, Hockham C, et al. Hemodiafiltration or hemodialysis and mortality in kidney failure. New England Journal of Medicine 389 (2023): 700-709.

- Kaller R, Russu E, Arbănaşi EM, et al. Intimal CD31-positive surfaces and inflammation in arteriovenous fistula maturation. Journal of Clinical Medicine 12 (2023): 4419.

- Miyasato Y, Hanna RM, Miyagi T, et al. Interdialytic weight gain in long intervals and mortality. Hemodialysis International 27 (2023): 326-338.

- Parati G, Bilo G, Kollias A, et al. Blood pressure variability: methodological aspects, relevance and management. Journal of Hypertension 41 (2023): 527-544.

- Rashid HU, Alam MR, Khanam A, et al. Nephrology in Bangladesh. Nephrology Worldwide (2021): 221-238.

- Kang SH, Kim BY, Son EJ, et al. Influence of β-blockers on mortality in hemodialysis patients. Biomedicines 11 (2023): 2838.

- Chrysant SG, Chrysant GS, et al. Association of hypomagnesemia with cardiovascular diseases and hypertension. International Journal of Cardiology Hypertension 1 (2019): 100005.

- Rantanen JM, Riahi S, Schmidt EB, et al. Arrhythmias in patients on maintenance dialysis: a cross-sectional study. American Journal of Kidney Diseases 75 (2020): 214-224.

- Sacher F, Jesel L, Borni-Duval C, et al. Cardiac rhythm disturbances in hemodialysis patients: early detection using an implantable loop recorder. JACC Clinical Electrophysiology 4 (2018): 397-408.

- Wong MC, Kalman JM, Pedagogos E, et al. Bradycardia and asystole as mechanisms of sudden cardiac death in chronic kidney disease. JACC 65 (2015): 1263-1265.

- Compagnucci P, Casella M, Bianchi V, et al. Implantable defibrillator-detected heart failure status predicts ventricular tachyarrhythmias. Journal of Cardiovascular Electrophysiology 34 (2023): 1257-1267.

- Fairley JL, Zhang L, Glassford NJ, et al. Magnesium status and magnesium therapy in cardiac surgery: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Critical Care 42 (2017): 69-77.

- Ishii S, Minatsuki S, Hatano M, et al. TAPSE-to-PASP ratio predicts prognosis in lung transplant candidates with PAH. Scientific Reports 13 (2023): 3758.

- Mazzanti A, Kukavica D, Trancuccio A, et al. Outcomes of patients with catecholaminergic polymorphic ventricular tachycardia treated with β-blockers. JAMA Cardiology 7 (2022): 504-512.

- Laboyrie SL, de Vries MR, Bijkerk R, et al. Building a scaffold for arteriovenous fistula maturation: the role of extracellular matrix. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24 (2023): 10825.

Impact Factor: * 3.3

Impact Factor: * 3.3 Acceptance Rate: 73.59%

Acceptance Rate: 73.59%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks