Methods and Safety of Exercise Testing in Older Adults: A Narrative Review

Singhasha Mog Choudhury*

Assistant Professor, Department of Physiotherapy, Techno India University

*Corresponding Author: Singhasha Mog Choudhury, Assistant Professor, Department of Physiotherapy, Techno India University

Received: 29 January 2026; Accepted: 03 February 2026; Published: 06 February 2026

Article Information

Citation: Singhasha Mog Choudhury. Methods and Safety of Exercise Testing in Older Adults: A Narrative Review. Archives of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation. 9 (2026): 20-25.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

For almost fifty years, clinical exercise testing has been a mainstay of cardiovascular evaluation, especially for ischemic heart disease (IHD) diagnosis, functional assessment, and prognostic stratification. Exercise testing for older adults has become more crucial in both clinical and preventive healthcare settings due to the world's rapidly growing senior population. However, aging is linked to progressive physiological changes, a higher burden of comorbidities, frailty, and functional limitations, all of which call for more stringent safety precautions, protocols, and testing modalities. The methods, indications, contraindications, risk stratification, protocol selection, and safety principles of exercise testing in older adults are all thoroughly examined in this narrative review. Submaximal, functional, and field-based evaluations, as well as customized protocol design, are given special attention.

Keywords

Exercise testing; Older adults; Cardiopulmonary exercise testing; Risk stratification

Article Details

1. Introduction

Clinical exercise testing has been utilized for more than 50 years as a diagnostic and prognostic modality in individuals with suspected or established cardiovascular disease, particularly ischemic heart disease (IHD). Although exercise testing serves multiple clinical purposes, its predominant application remains the detection of myocardial ischemia and the evaluation of functional capacity. Commonly used terms include graded exercise testing (GXT), exercise stress testing, and exercise tolerance testing (ETT). When exercise testing incorporates the measurement of expired gases, it is referred to as cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET), also known as exercise metabolic testing [1]. The ongoing demographic transition toward a globally aging population poses both significant challenges and important opportunities for healthcare systems worldwide. In 2019, approximately one billion individuals were aged 60 years or older, and this number is projected to increase to 2.1 billion by 2050. Likewise, the population aged 65 years and above is expected to grow from 770 million in 2022 to nearly 1.6 billion by 2050. Older adults exhibit a high prevalence of cardiovascular disease, frailty, multimorbidity, and functional impairment, which makes exercise testing clinically valuable yet methodologically complex. As a result, exercise testing in elderly populations necessitates careful protocol selection and enhanced safety considerations to ensure accurate, feasible, and safe assessment [2,3]. This narrative review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of exercise testing methods and safety considerations in older adults, with particular attention to clinical indications, contraindications, risk stratification, physiological monitoring, protocol selection, and functional applicability.

2. Clinical Indications for Exercise Testing

Exercise stress testing is a well-established diagnostic tool for evaluating coronary artery disease (CAD) in symptomatic individuals and for prognostic risk stratification in patients with known cardiac conditions. In elderly populations, exercise testing is particularly useful for assessing functional capacity, guiding clinical decision-making, evaluating therapeutic interventions, and determining prognosis.

2.1. Diagnostic Indications

- • Evaluation of chest pain in individuals with an intermediate pretest probability of CAD.

- • Detection and assessment of exercise-induced arrhythmias.

- • Investigation of exertional symptoms such as dizziness, presyncope, and dyspnea.

2.1.2. Prognostic Indications

- • Risk stratification following myocardial infarction.

- • Prognostic evaluation in hypertrophic and dilated cardiomyopathies.

- • Assessment of treatment effectiveness following revascularization or pharmacological therapy.

- • Evaluation of exercise tolerance and overall cardiac function.

- • Assessment of cardiopulmonary limitations in patients with heart failure.

Routine exercise testing is not recommended for screening asymptomatic individuals. Furthermore, exercise testing is generally not indicated in patients with stable coronary artery disease who remain asymptomatic within two years of percutaneous coronary intervention or within five years of coronary artery bypass grafting [1].

3. Risk Stratification Prior to Exercise Testing

Appropriate risk stratification is fundamental to minimizing adverse events and optimizing the diagnostic and prognostic value of exercise testing. The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) classifies individuals into low-, moderate-, and high-risk categories based on clinical presentation and cardiovascular risk factors.

4. Low-Risk Individuals

Low-risk individuals are asymptomatic and have no known cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic disease, with no more than one cardiovascular risk factor. These individuals may participate in physical activity and undergo exercise testing without mandatory medical clearance.

5. Moderate-Risk Individuals

Moderate-risk individuals are asymptomatic but possess two or more cardiovascular risk factors. Although low- to moderate-intensity exercise is generally safe, medical evaluation and exercise testing are recommended prior to initiating vigorous-intensity activity.

6. High-Risk Individuals

High-risk individuals have known cardiovascular, pulmonary, or metabolic disease or exhibit signs and symptoms suggestive of such conditions. In these cases, a comprehensive medical examination and physician-supervised exercise testing are mandatory before initiating any exercise program. Risk stratification is particularly critical in older adults due to the increased prevalence of subclinical disease, reduced physiological reserve, and a higher incidence of exercise-induced arrhythmias [1].

7. Contraindications to Exercise Testing

Careful consideration of absolute and relative contraindications is essential prior to exercise testing in elderly individuals. Absolute contraindications include:

- • Recent acute myocardial infarction (within 4–6 days).

- • Unstable angina.

- • Uncontrolled heart failure.

- • Acute myocarditis or pericarditis.

- • Acute systemic infections.

- • Severe uncontrolled hypertension.

- • Severe aortic stenosis

- • Life-threatening arrhythmia.

- • Recent major vascular surgery.

Strict adherence to these contraindications is essential to ensure patient safety during exercise testing [1].

8. Principles and Preparation for Exercise Testing

Exercise testing involves systematic and progressive increase of workload through adjustments in treadmill speed and grade or cycle ergometer resistance. Important principles include:

- • Selection of a low initial workload appropriate to the individual’s aerobic capacity.

- • Maintenance of each workload stage for at least one minute.

- • Continuous monitoring of electrocardiogram (ECG), blood pressure, and patient-reported symptoms.

- • Immediate test termination upon the development of significant symptoms, abnormal hemodynamic responses, or ECG changes.

All individuals should undergo a pre-test physical examination, provide informed consent, and receive continuous monitoring throughout both the exercise and recovery phases [1].

9. Physiological Monitoring and Safety Considerations

Exercise testing elicits predictable cardiopulmonary responses that require vigilant monitoring in older adults. Heart rate and blood pressure typically increase proportionally with exercise intensity, with systolic blood pressure rising by approximately 7–10 mmHg per metabolic equivalent (MET). Abnormal responses, excessive blood pressure elevations, abnormal ventilatory patterns, or symptoms such as angina and severe dyspnea necessitate immediate test termination. Continuous ECG monitoring is strongly recommended in adults over 65 years of age due to the increased prevalence of exercise-induced dysrhythmia. Large-scale studies have demonstrated that, when standardized safety protocols are followed, the incidence of serious adverse events during Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) in older adults remains low and comparable to that observed in younger populations [1].

10. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET)

(CPET) is the gold standard for assessing integrated cardiovascular, pulmonary, and metabolic responses during exercise. By analyzing breath-by-breath gas exchange, CPET provides direct measurement of peak oxygen uptake (VO2 peak), ventilatory thresholds, and gas exchange efficiency, offering superior diagnostic and prognostic value compared with conventional exercise testing, particularly in older adults with multisystem disease. CPET is especially valuable for identifying the primary contributors to exercise intolerance—cardiac, pulmonary, peripheral, or deconditioning-related—and for informing risk stratification, preoperative evaluation, and individualized exercise or rehabilitation planning. In older adults, CPET is feasible and safe when conducted under tailored supervision, with studies showing low adverse event rates comparable to younger populations. Treadmill testing typically elicits higher VO2 peak, while cycle ergometry provides greater stability and ease of monitoring for frail individuals. Overall, CPET offers comprehensive physiological insight and supports clinical decision-making, though its use should be guided by functional capacity, clinical indication, and available expertise [4].

11. Maximal Versus Submaximal Exercise Testing

Maximal exercise testing provides superior diagnostic sensitivity and enables direct measurement of maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max) and anaerobic threshold. However, it requires exercise to volitional fatigue and often necessitates physician supervision and immediate access to emergency equipment. Submaximal exercise testing is more frequently employed in elderly populations due to its lower physiological demand and reduced risk. These tests estimate VO2 max based on heart rate responses to predetermined workloads and are particularly useful in health, rehabilitation, and community settings where maximal testing may not be feasible [1,5].

12. Modes of Exercise Testing

12.1 Treadmill Testing

Treadmill testing is commonly used in clinical practice because it closely resembles normal ambulation. Older adults generally achieve higher peak oxygen consumption and heart rate on treadmills compared with cycle ergometers. However, balance limitations and challenges in obtaining accurate blood pressure measurements may restrict its use in frail individuals [1,5].

12.2 Cycle Ergometry

Cycle ergometers provide a stable, non–weight-bearing alternative that allows precise ECG and blood pressure monitoring. Although cycle testing may underestimate aerobic capacity due to early localized muscle fatigue, it is often preferred in elderly individuals because gait instability during treadmill testing may compromise safety and test validity. Protocols with modest workload increments, such as the Naughton protocol, are recommended, particularly in elderly individuals recovering from conditions such as COVID-19 [1,7].

12.3 Step Testing

Step tests offer an inexpensive method for estimating cardiovascular fitness but may be unsuitable for individuals with balance impairments or severe deconditioning. Recovery heart rate following step tests provides a simple indicator of cardiovascular fitness [1].

12.4 Field and Functional Exercise Tests

Functional exercise tests reflect activities of daily living and are particularly well tolerated in elderly populations. Some of the field and functional tests are as follows.

13. Canadian Aerobic Fitness Test (CAFT) and Modified CAFT

The CAFT can be administered in home, clinic, or are as follows. Things using minimal equipment, including a double 20.3-cm step, heart rate monitor, prerecorded audiotape, sphygmomanometer, stethoscope, and stopwatch. The protocol involves progressive stepping stages guided by age-specific cadence, with heart rate measured post-stage and test termination based on ceiling heart rate values. Post-exercise blood pressure and heart rate recovery are also assessed [5].

14. Rockport Walk Test

The Rockport Walk Test involves walking one mile as fast as possible and estimating VO2max using age, weight, walk time, and heart rate. It is suitable for individuals of low fitness across all age groups, including the elderly, and requires minimal equipment [8].

15. Self-Paced Walking Test (SPWT)

The SPWT was developed for elderly and frail individuals and consists of free walking at three self-selected speeds over a 250-m corridor. Variables assessed include walking speed, stride characteristics, heart rate, and predicted VO2max [5].

16. Modified Shuttle Walking Test (MSWT)

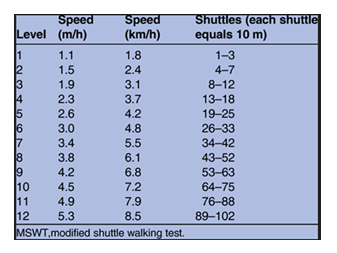

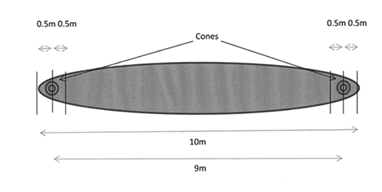

Originally designed for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, the MSWT has been validated in older and symptomatic populations, including cardiac patients, coronary artery bypass graft recipients, pacemaker patients, and individuals with heart failure. Distance covered during the MSWT correlates strongly with directly measured VO2peak [9].

Modified Shuttle walking test protocol

17. The incremental modified shuttle walking test (MSWT)

Originally developed for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients, is now recommended for older and symptomatic individuals, such as cardiac patients,including coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) patients,those with pacemakersand heart failure.Distance covered during MSWT has been found to correlate highly with direct measures of VO2max in CABG patients as well as distance walked and VO2peak during treadmill walking in patients with heart failure.MSWT, therefore, offers a practical, economic and valid assessment of the VO2peak without resorting to complex physiological measures of gas analysis [9].

Layout of modified shuttle walking test

18. Bag and Carry Test (BCT)

The BCT assesses combined endurance and muscle strength by requiring participants to walk a circuit while carrying progressively heavier loads. The test is easy to administer and suitable for higher-functioning older adults [5].

19. Timed Up and Go (TUG) Test

The TUG assesses functional mobility by timing the task of standing from a chair, walking 3 m, turning, returning, and sitting. It is widely used in geriatric assessment [5].

20. 6-Minute and 12-Minute Walk Tests

Both tests assess submaximal functional capacity by measuring distance walked over a defined time. Standardized encouragement and monitoring protocols are recommended to ensure consistency and safety.

- • For the 12-MWT, the individual is instructed to cover as much ground as possible on foot in 12 minutes and to keep going continuously if possible but not to be concerned if you have to slow down or rest at the end of the test, subjects should feel they could not have covered more ground in the time

- • For the 6-MWT, the individual is instructed to walk from end to end, covering as much ground as possible in 6 minutes at the end of the 6 or 12 min, the individual is instructed to stop; the total distance is recorded

- • If encouragement is given, predetermined phrases should be delivered every 30 s while facing the individual Report the total distance covered (in meters).

- • On completion of the test, the individual should continue walking to cool down [5].

21. Two Chair Test (2CT)

The Two Chair Test (2CT) was developed as a space-efficient alternative to the 6-Minute Walk Test. It involves repeated transitions between two chairs placed 5 feet apart, with post-exercise monitoring of pulse rate and oxygen saturation. Studies demonstrate excellent reproducibility, strong correlation with physiological responses observed in the 6MWT, and high cardiopulmonary reserve specificity, making it a practical submaximal assessment tool for settings with space constraints [11].

22. Exercise Protocol Selection

Exercise protocol selection should be individualized according to functional capacity, clinical objectives, and safety considerations. The standard Bruce protocol incorporates relatively large and unequal increments in workload, which may be poorly tolerated and can result in premature test termination in older adults. Although the modified Bruce protocol reduces initial exercise intensity through the inclusion of warm-up stages, it still follows a stepwise workload progression that may be challenging for some elderly or markedly deconditioned individuals. Consequently, protocols employing smaller and more continuous increases in workload—such as ramp, Naughton, and Balke-Ware protocols—are often preferred in these populations. In the standard Bruce protocol, testing begins at stage 1 with a treadmill speed of 1.7 mph and a 10% grade, corresponding to approximately 5 metabolic equivalents (METs). Workload is increased every 3 minutes by progressively raising both speed and incline, with stage 2 at 2.5 mph and a 12% grade (≈7 METs) and stage 3 at 3.4 mph and a 14% grade (≈9 METs). The 3-minute stage duration allows sufficient time for the achievement of a steady-state physiological response before advancement to higher workloads.

The modified Bruce protocol incorporates two initial low-intensity warm-up stages, each lasting 3 minutes, performed at 1.7 mph with 0% and 5% grades, respectively. These preliminary stages improve test tolerability and safety compared with the standard Bruce protocol and make the modified Bruce protocol suitable for many older adults and individuals with limited exercise capacity due to cardiovascular disease. However, in very frail or severely deconditioned patients, protocols with more gradual and continuous workload progression may be more appropriate [4].

23. Balke & ware treadmill exercise test

The balke & ware treadmill test is another common treadmill test used in both clinical and fitness settings to assess cardiorespiratory fitness. The test is administered in one- to three-minute stages until the desired HR is achieved or symptoms limit test completion. In a clinical setting, the test is typically performed to maximal effort, to evaluate cardiac function in addition to fitness. When performed in a fitness setting, this test should be terminated when the client achieves 85% of his or her age-predicted MHR. Since speed is held constantly, this test is more appropriate for deconditioned individuals, the elderly, and those with a history of cardiovascular disease [12].

Balke and ware treadmill exercise protocol

24. Ramp Protocol Procedure

Every participant inthe study by Kozlov andcolleagues(40 patients aged ≥70 years withouta history ofconfirmedheart failure orcoronary arterydisease) had two days oftreadmill exercise testing using both the modified Bruce protocoland anindividualized rampprotocol. Participants startedwalking on an Inter Track treadmill at a speed of 1.6 km/h withno inclination as part of the customized ramp protocol. Thelowinitialworkload wasselectedtoaccount forthe functional capacity and balanceissues that are common among older participants. Throughout the test,treadmill speed and incline werebothincreased linearly and continuously until maximum values wereattained, resultingina gradual, smooth increase in workload. The maximumtreadmill incline was also age- andsex-specific: o4.0 km/h for men aged 70–79 years and 3.2 km/h for men aged ≥80 years, as well as for all women [4].

25. Pharmacological Stress Testing

In elderly individuals unable to perform adequate physical exercise, pharmacological stress testing may be employed using vasodilators or inotropic agents. Approved vasodilators include adenosine, dipyridamole, and regadenoson, which induce coronary steal phenomena rather than true myocardial stress. Regadenoson is most used due to its receptor selectivity and favorable side-effect profile. Dobutamine may be used in selected patients with contraindications to vasodilators.

26. Indications

- • Patients who are unable to tolerate exercise stress test due to abnormalities involving the respiratory system (severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)), provoked angina, hypotension during exercise, chronotropic incompetence. These patients are suitable candidates for testing involving pharmacologic agents.

- • Patients who have baseline abnormal electrocardiogram which include the presence of left bundle branch block at baseline, left ventricular hypertrophy, paced rhythm, Wolf Parkinson White syndrome, and greater than 1 mm ST-segment depression. These patients can have false-positive results on an exercise stress test.

- • Symptomatic aortic stenosis.

27. Contraindication

|

Stress Agent |

Main Contraindications |

|

Adenosine |

Reactive airway disease, AV block, sinus node disease, hypotension, severe hypertension, caffeine intake, hypersensitivity, recent ACS |

|

Dipyridamole |

Bronchospasm, uncontrolled hypertension, hypotension |

|

Regadenoson |

AV block/sick sinus syndrome, allergy to agent, hypotension, uncontrolled hypertension, recent dipyridamole, recent ACS |

|

Dobutamine |

Recent ACS, LV outflow obstruction, uncontrolled arrhythmias, severe hypertension, aortic dissection [1,13]. |

28. Conclusion

Exercise testing in older adults should focus on assessing functional capacity rather than maximal performance. Combining laboratory-based evaluations with functional and field-based tests enhances safety, adherence, and clinical relevance. When appropriately selected, supervised, and tailored to the individual, exercise testing is a safe and valuable tool for evaluating cardiovascular function, exercise tolerance, and overall functional capacity. Advances in protocol design, personalized risk assessment, and safety monitoring have made exercise-based assessments more feasible in older populations. A function-centered, patient-specific approach enables clinicians to minimize risk while obtaining meaningful diagnostic and prognostic information. Integrating laboratories, field, and functional testing will be essential for optimizing cardiovascular care, guiding rehabilitation, and improving quality of life as the older adult population continues to grow.

References

- Walter R. Thompson. American college of sports medicine. ACSM’s Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription eighth edition. (2019).

- “Ageing.” Accessed January 22, (2026).

- Zhou, Mengge, Guanqi Zhao, et al. “Aging and Cardiovascular Disease: Current Status and Challenges.” Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine 23 (2022): 135.

- Kozlov, Sergey, Martin Caprnda, et al. “Peak Responses during Exercise Treadmill Testing Using Individualized Ramp Protocol and Modified Bruce Protocol in Elderly Patients.” Folia Medica 62 (2020): 76-81.

- Submaximal Exercise Testing: Clinical Application and Interpretation. (2026).

- Vilcant, Viliane, and Roman Zeltser. “Treadmill Stress Testing.” (2025).

- Venturelli, Massimo, Emiliano Cè, et al. “Maximal Aerobic Capacity Exercise Testing Protocols for Elderly Individualsin the Era of COVID-19.” Aging Clinical and Experimental Research 33 (2021): 1433-1437.

- Topend Sports. “Topend Sports | Sports Science, Fitness Testing & Event Analysis.” (2026).

- Woolf-May, Kate, Steve Meadows. “Exploring Adaptations to the Modified Shuttle Walking Test.” BMJ Open 3 (2013): e002821.

- Matos Casano, Harold A, Intisar Ahmed, et al. “Six-Minute Walk Test.” In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing (2025).

- Bhattacharyya, Parthasarathi, Dipanjan Saha, et al. “Two Chair Test: A Substitute of 6 Min Walk Test Appear Cardiopulmonary Reserve Specific.” BMJ Open Respiratory Research 7 (2020).

- “TreadmillExerciseTesting.Pdf.” (2026).

- Lak, Hassan Mehmood, Sagar Ranka, et al. “Pharmacologic Stress Testing.” (2025).

Impact Factor: * 1.3

Impact Factor: * 1.3 Acceptance Rate: 73.39%

Acceptance Rate: 73.39%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks