Assessment of the Efficacy of a Food Supplement in Subjects Complaining Primary Dysmenorrhea - the Triangirl-feel Good Study

Rita Mocciaro1, Amelia Spina2, Maite Pérez-Hernández3, Roser de Castellar-Sansó3*

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, “SS. Annunziata” Ospedaliera di Cosenza, Italy

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Nutratech S.r.l., Spin-Off of University of Calabria, Rende, Italy

3Department of Medical Affairs, Laboratorios Ordesa SL, Barcelona, Spain

* Corresponding author: Roser de Castellar-Sansó. Department of Medical Affairs, Laboratorios Ordesa SL, Barcelona, Spain.

Received: 25 August 2025; Accepted: 01 September 2025; Published: 03 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Rita Mocciaro, Amelia Spina, Maite Pérez-Hernández, Roser de Castellar-Sansó. Assessment of the Efficacy of a Food Supplement in Subjects Complaining Primary Dysmenorrhea - the Triangirl-feel Good Study. Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 8 (2025): 186-196.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background:

Primary dysmenorrhea, characterized by painful abdominal cramping before and during menstruation without pelvic pathology, significantly affects quality of life (QoL). First-line treatments, such as non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and hormonal contraceptives, have suboptimal efficacy and tolerability in some patients, increasing interest in alternative therapies like dietary supplements.

Objective:

This study assessed the effectiveness and safety of a dietary supplement combining palmitoylethanolamide, ginger root extract, and fennel seed extract in alleviating primary dysmenorrhea symptoms.

Methods:

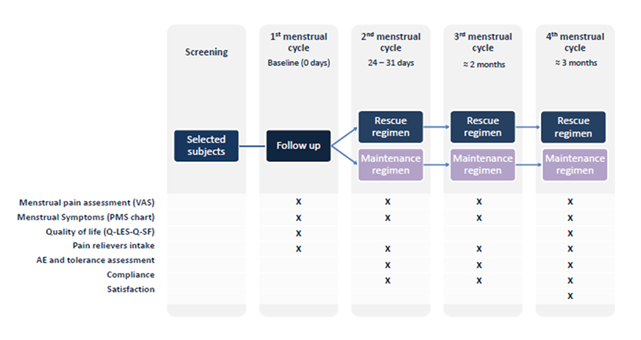

56 women (18–30 years) were randomized into two regimens: the maintenance regimen (supplement taken three days before and two days into menstruation) and the rescue regimen (taken at pain onset). Pain intensity was measured using the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), and QoL was assessed with the Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire - Short Form (Q-LES-Q-SF) questionnaire. The study spanned four menstrual cycles, with one cycle serving as a control group that did not undergo any treatment, and three cycles undergoing treatment. The researchers measured outcomes over the course of three menstrual cycles. In addition, adherence to treatment and the presence of any adverse effects were closely monitored.

Results:

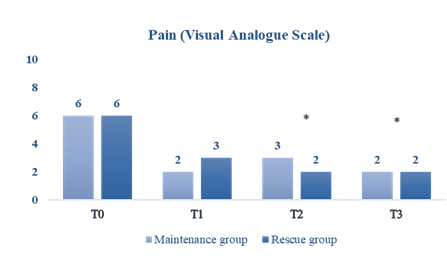

Both regimens effectively reduced pain, with a greater and sustained effect observed in the maintenance group. By the third and fourth cycles, VAS scores decreased from 6 to 2 in both groups, with a more pronounced QoL improvement in the maintenance group (22.8% vs. 19.5%). The supplement reduced analgesic use and was well tolerated, with no reported adverse effects.

Conclusion:

The dietary supplement effectively alleviated primary dysmenorrhea symptoms and improved QoL, particularly with the maintenance regimen. These findings support the potential of dietary supplements as safe, non-pharmacological options for managing menstrual pain.

Keywords

Primary dysmenorrhea; Menstrual pain; Dietary supplement; Palmitoylethanolamide; Ginger; Fennel

Article Details

Introduction

Primary dysmenorrhea is defined as painful, spasmodic cramping in the lower abdomen that occurs just before and/or during menstruation in the absence of pelvic pathology [1]. The underlying mechanism of primary dysmenorrhea seems to involve the increased synthesis and release of prostaglandins, which results in the hypercontractility of the myometrium. This leads to the onset of uterine muscle ischemia and subsequent hypoxic conditions, leading to the sensation of pain [2]. The pain usually persists for 8 to 72 hours and is most severe on the first and second days of menstrual bleeding due to increased prostaglandin release. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, back pain, migraine, dizziness, fatigue and insomnia [3].

Dysmenorrhea affects over 50% of women [4] and its prevalence increases to 60-80% in adolescents [5,6], leading to high rates of school and work absenteeism, as well as decreasing quality of life (QoL) [3]. In a study conducted in Portugal, 8.1% of girls reported missing school or work due to menstrual pain, impacting daily activities in approximately 65.7% of cases [7]. Dysmenorrhea mainly affects academic performance in terms of concentration, sport, socialization, and school achievement. Furthermore, it influences pain tolerance and causes disturbances in sleep patterns, resulting in daytime fatigue and a general sense of lethargy [3].

Therapeutic options for primary dysmenorrhea are aimed at interfering with progesterone production, reducing uterine tone, or inhibiting pain perception by direct analgesia. Generally, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) have largely been established as the first-line therapy for primary dysmenorrhea [8]. However, a Cochrane systematic review suggests that only between 45% and 53% taking NSAIDs achieve moderate or excellent pain relief [9]. Moreover, adolescent girls tend not to follow the maximum recommended dosage on over the counter (OTC) medication labels, as shown in a study which assessed the use of medication by adolescents to manage menstrual discomfort. According to this study, only 31% took the recommended dose of 1–2 pills at the maximum suggested daily frequency (3–4 times per day). More than half (56%) used OTC medications less frequently, which suggests that some adolescents may experience inadequate relief as they switch to less aggressive alternatives [10].

Hormonal contraceptives are also regarded as the primary treatment option for dysmenorrhea, unless precluded by contraindications. They are typically recommended for women experiencing dysmenorrhea who also require contraception, for whom the use of contraceptives is deemed acceptable, or for those who are unable to tolerate or unresponsive to NSAIDs [11]. Nevertheless, the use of oral contraceptives is associated with a range of potential adverse events (AEs), many of which are related to the hormones which are part of their pharmacological composition. While the use of estrogens is associated with nausea, vomiting, headaches, breast tenderness and changes in body weight, the use of progestogens has been linked with the appearance of acne, weight gain, increased hair growth and depression. Furthermore, in high doses, they can induce circulatory disorders and thromboembolic episodes [12].

Beyond the well-established pharmacological therapies, supplementary strategies for dysmenorrhea may be employed in conjunction with or in the absence of pharmacological agents. All pharmacologic interventions may be associated with AEs, leading patients to pursue lifestyle modifications prior to taking medication to avoid unwanted side-effects. In a review that analyzed the most common self-care options for young women, rest, heat therapy, herbal medicine or teas, and exercise were identified as the most prevalent self-care strategies [13]. Among the aforementioned alternatives, dietary supplements comprising components with well-established scientific evidence have demonstrated efficacy and safety in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea.

This study was performed in order to evaluate the efficacy and safety of a dietary supplement formulated with palmitoylethanolamide (PEA), ginger root extract and fennel seed extract in subjects suffering mild/moderate primary dysmenorrhea.

Material and Methods

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set out in the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and in compliance with the ethical principles which apply to medical research. The study protocol was approved by the independent Ethical Committee “Comitato Etico Indipendente per le indagini Cliniche Non Farmacologiche” on December 14th 2023.

The study was carried on 2 groups of subjects. Both were homogeneous for age (60% 16-24 years old; 40% ≥24 years old) and were defined according to the onset of pain (50% the days before the cycle; 50% during the cycle).

Two different aims were foreseen in accordance with a different way of product intake:

- • The maintenance regimen group was instructed to take one tablet twice a day, with a minimum of six hours between doses, for a period of three days prior to the onset of the menstrual cycle and for two days during the initial phase of the menstrual cycle.

- • The rescue regimen group was instructed to ingest one tablet upon the onset of pain. In the event of persistent discomfort, it was recommended that a second tablet could be taken after a period of two hours, with a maximum of two tablets permitted per day.

A total of 56 subjects were enrolled in the study. Efficacy analysis was based on the Per Protocol (PP) Population, which is defined as all subjects who complete the study without any major protocol violations. Subjects were excluded from the PP population if: they missed the one or more evaluation visit; or they did not use the product properly during the study period (as referred by the subject itself). Data were summarized using frequency distributions (number and percentage) for categorical/ordinal variables. For continuous variables the following figures were calculated: i) the mean value, ii) the minimum value, iii) the maximum value, iv) the standard deviation, v) the standard error of the mean (SEM), vi) the individual variation, vii) the mean variation, viii) the individual percentage variation, ix) the mean percentage variation.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were established as shown in Supplemental Material S1.

The study duration took around 4 months (1 month without intervention at T0 and 3 months of product intake: at T1, T2, T3). Following the initial screening visit, the participants were instructed on the proper method for data collection during the first cycle. They were then scheduled for a subsequent visit after this cycle, which was to occur without treatment. Subsequent visits were scheduled after each cycle of treatment.

The primary objective was to evaluate the effectiveness of the nutritional supplement in providing relief from menstrual pain and other discomforts associated with the menstrual cycle. Secondary objectives were the evaluation of the reduction in the regular need for pain relievers (such as NSAIDs, e.g., ibuprofen), the evaluation of the product's safety through the monitoring of AEs and the evaluation of improvement in QoL.

To achieve these objectives, several validated assessment tools were employed. The Quality-of-Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire–Short Form (Q-LES-Q-SF), a 16-item self-administered questionnaire, was used to measure life satisfaction over the past months. The Premenstrual Syndrome Symptoms Scale (PMS Scale) was utilized to assess the severity of premenstrual symptoms, including depressive mood, anxiety, fatigue, irritability, pain, appetite and sleep disturbances, and swelling. Menstrual pain intensity was evaluated using a numerical rating scale from 0 to 10, where 0 indicated no pain and 10 represented the highest level of pain experienced. Additionally, a self-assessment questionnaire was used to gauge participants' subjective perceptions, scored on a scale from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating the worst or total disagreement and 10 representing the best or total agreement.

Results

The mean age of the participants was 23 years (ranging from 18 to 29 years), with a mean body mass index (BMI) within the normal range. Of the participants, 60% were younger than 24 years old (Table 1).

There were three cases of polycystic ovaries in the rescue regimen group and one case in the maintenance regimen group.

Table 1: Study population.

|

|

Rescue |

Maintenance Regimen |

Total |

||

|

Age |

Mean |

23.3 |

23 |

23.1 |

|

|

SD |

3.1 |

3.3 |

3.1 |

||

|

Max |

29 |

29 |

29 |

||

|

Min |

18 |

19 |

18 |

||

|

Heigh (cm) |

Mean |

163.6 |

164.7 |

164.1 |

|

|

SD |

7.3 |

6 |

6.6 |

||

|

Max |

175 |

177 |

177 |

||

|

Min |

149 |

154 |

149 |

||

|

Weight (kg) |

Mean |

60.2 |

60.6 |

60.4 |

|

|

SD |

10.2 |

8.7 |

9.4 |

||

|

Max |

80 |

80 |

80 |

||

|

Min |

40 |

41 |

40 |

||

|

BMI |

Mean |

22.5 |

22.4 |

22.4 |

|

|

SD |

3.2 |

3.3 |

3.2 |

||

|

Max |

28.3 |

28.7 |

28.7 |

||

|

Min |

16.6 |

15.3 |

15.3 |

||

|

Menarche (age) |

Mean |

12.5 |

12.4 |

12.5 |

|

|

SD |

1.2 |

0.9 |

1.1 |

||

|

Max |

16 |

14 |

16 |

||

|

Min |

10 |

11 |

10 |

||

SD: standard deviation; BMI: body mass index

In order to assess the reduction in menstrual discomfort experienced by the female subjects, a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) was employed to evaluate pain, with scores ranging from 0 to 10 (0-1: no pain; 2-3: mild; 4-5: moderate discomfort; 6-7: severe pain; 8-9: very severe pain; 10: most pain possible).

In general, the intensity of the menstrual pain decreased significantly from baseline in both groups (p<0.001) (Figure 2).

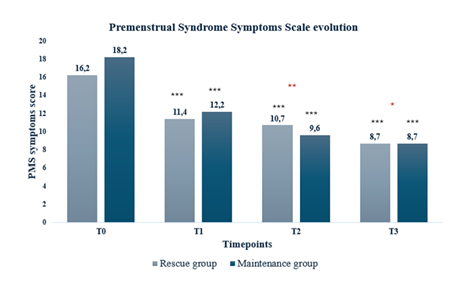

The assessment of menstrual symptoms using PMS Scale revealed a significant decline in both cohorts, with a decrease of the PMS score in cycles 2, 3 and 4 (p<0.001) as compared to the cycle 1. Furthermore, a significantly greater reduction was observed in the maintenance regimen group with respect to the rescue regimen group at T2 (p<0.01) and T3 (p<0.05). Women taking the supplement in a short treatment regimen achieved a mean percentage change at T3 from baseline of 46.7% and those with a long treatment regimen had a change of 53.7%.

The self-assessment questionnaire, based on a 0–10 visual analogue scale (0 = the worst/totally disagree; 10 = the best/totally agree), explored three main aspects: perceived efficacy, ease of swallowing, and adherence to the dosing regimen. With regard to perceived efficacy in alleviating menstrual discomfort, 86% of women treated with the rescue regimen and 96% of those in the maintenance regimen gave scores higher than 5. Concerning ease of administration, 93% of participants in both groups reported that the tablet was easy to swallow. Finally, adherence to treatment was very positively assessed, with 96% of women in the rescue regimen and 100% in the maintenance regimen indicating no difficulties in following the prescribed dosage schedule.

Regarding the use of pain relievers, at baseline (cycle without supplementation) 25% of women in the rescue regimen group and 37% in the maintenance regimen group reported taking analgesics. In the following cycles, these percentages decreased to 11% at T1, 11% at T2, and 14% at T3 in the rescue regimen group, and to 19% at T1, 22% at T2, and 19% at T3 in the maintenance regimen group. When considering the entire study population, the mean number of pain relievers consumed per participant decreased from 0.76 tablets at baseline to 0.25 at T1, 0.29 at T2, and 0.29 at T3.

The QoL, as measured by Q-LES-Q-SF demonstrated a statistically significant improvement with both regimens, resulting in an increase of 19.5% in the rescue regimen group (T0 vs. T3; p<0.01) and an increase of 22.8% in the maintenance regimen group (T0 vs. T3; p<0.05).

In terms of safety, the supplement was found to be safe and well tolerated, as there were no discontinuations or withdrawals and no AEs reported.

Discussion

While NSAIDs and oral contraceptives are typically regarded as the first-line treatment for primary dysmenorrhea, there is an emerging interest in exploring alternative medical resources among both patients and healthcare professionals. The use of non-pharmacological interventions is a common practice among females experiencing dysmenorrhea, as many women attempt lifestyle modifications prior to taking medication in order to avoid the unwanted side effects that may result from such interventions [14]. A recent meta-analysis, which included 12,526 females with dysmenorrhea, revealed that 51.8% of them relied on various non-pharmacological strategies to manage their menstrual discomfort. It is noteworthy that the study revealed a low percentage (11%) of female participants who sought professional medical treatment regarding the alleviation of their symptoms [13].

Among these non-pharmacological alternatives, herbal and dietary therapies represent a growing area of interest in the field of complementary medicine. The administration of a dietary supplement containing PEA, ginger extract, and fennel root extract has proved an effective and safe approach to alleviating menstrual symptoms. This finding is consistent with the results of previous scientific studies and literature on these components.

PEA is an endocannabinoid-like bioactive lipid mediator which is synthesized on demand within the lipid bilayer and acts locally [15]. It has been suggested that PEA is produced as a pro-homeostatic protective response to cellular injury and is usually up-regulated in disease states [16]. Its pleiotropic effects include anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anticonvulsant, antimicrobial, antipyretic, antiepileptic, immunomodulatory, and neuroprotective activities [17-21]. In a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial with 220 women aged 16 to 24 years with primary dysmenorrhea, a greater proportion of those taking PEA supplement experienced improvement in pelvic pain (98.2% of cases compared to 56.36% in the placebo group) [22]. Furthermore, another recent randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled crossover trial evaluated the efficacy and safety of 300 mg of PEA for the management of acute menstrual pain in 80 healthy adult women. Pain intensity was assessed using the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NRS) every 30 minutes for up to 4 hours. The results demonstrated a significant reduction in pain scores with PEA compared to placebo at 1 hour (p = .045), 1.5 hours (p = .009), 2 hours (p = .015), and 2.5 hours (p = .039) post-dose, with reported side effects being mild and infrequent [23].

In another observational study, 610 patients unable to adequately manage chronic pain with conventional therapies were administered PEA (600 mg) twice daily for three weeks, followed by a single daily dose for an additional four weeks, in conjunction with standard analgesic therapies or as a single therapy. The results showed that PEA treatment led to a substantial reduction in mean pain intensity scores across all patients who completed the study, without any discernible influence of the underlying pathological condition on this effect. The PEA-induced decrease in pain intensity was also observed in patients who did not receive concomitant analgesic therapy, and no AEs were reported [24]. Furthermore, despite the lipophilic nature of PEA, which presents a challenge to absorption, the product under assessment represents a form of PEA which has been enhanced through a specific technology, thereby increasing its solubility in aqueous environments. This has resulted in plasma concentrations that are 1.75 times higher than those observed with generic PEA [25]. The supplement used in this study contained 700 mg of PEA with this particular technology.

As for the other components, Zingiber officinale Roscoe, commonly known as ginger root, is utilized globally as a spice, seasoning, and traditional medicine. The pharmacological activities of ginger and its components are pleiotropic, encompassing gastrointestinal, antioxidant, cardiovascular, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory properties (26). Gingerols and shogaols are the main bioactive constituents responsible for ginger's analgesic properties and have been identified as agonists of transient receptor potential cation channel subfamily V member 1 (TRPV1), which is involved in the transduction of physical and chemical stimuli [27]. Prolonged exposure to agonists such as shogaols has been shown to desensitize TRPV1, leading to the alleviation of pain [28]. In the context of ginger's potential analgesic properties, studies have consistently demonstrated its efficacy in the treatment of dysmenorrhea. In a double-blind, comparative trial of 150 women with primary dysmenorrhea, 1,000 mg of ginger was found to be as effective as taking NSAIDs. Upon completion of the study, no discernible difference was observed in the reduction of dysmenorrhea symptoms and pain between the ginger, ibuprofen (400 mg), and mefenamic acid (250 mg) groups [29]. The supplement under examination in this study contains an extract of ginger root (15:1), which is equivalent to a quantity of plant powder ranging from 500 to 1,000 mg.

With regard to fennel, Foeniculum vulgare is a plant with an ancient history of use as a food source, an aromatic agent, and a medicinal remedy. Its chemical composition has been shown to possess antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, hepatoprotective, antimicrobial, and antiviral properties [30]. In particular, the component imperatorin has been identified as the most notable agent in its capacity to impede the synthesis of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor. [31]. As research has shown, fennel can reduce menstrual pains by lowering the level of prostaglandins in blood circulation [32]. Indeed, a meta-analysis of multiple clinical trials provided evidence that it may serve as an efficacious alternative treatment for reducing pain associated with primary dysmenorrhea, comparable to the efficacy of NSAIDs [33]. Moreover, a controlled clinical study of 80 women aged 18 to 23 years which followed an 8-day regimen of 1200 mg of fennel resulted in a significant reduction in the symptoms of primary dysmenorrhea. The group taking fennel demonstrated a notable decrease in the manifestations of menstrual discomfort, pain, and the overall number of days spent bleeding [32]. The supplement assessed in this study contains an extract of fennel seed (4:1), which is equivalent to 500–1,000 mg of fennel powder.

This study presents several strengths that contribute to the robustness of its findings. First, the randomized design and clear distinction between the two dosing regimens (maintenance regimen vs. rescue regimen) allow for a comparative assessment of different administration strategies, providing valuable insights into optimizing the use of the dietary supplement for primary dysmenorrhea. Second, the use of validated tools such as the VAS, the PMS Scale, and the Q-LES-Q-SF enhances the reliability of the reported outcomes. Furthermore, participants completed a self-assessment questionnaire that collected positive feedback regarding the ease of swallowing the tablet and complying with the dosing regimen, thus denoting adequate adherence to the treatment. Moreover, the study spans multiple menstrual cycles, allowing for an evaluation of the sustained effects of supplementation, which is often lacking in similar trials that assess short-term outcomes.

Another key strength is the comprehensive assessment of safety, showing no reported adverse effects, which reinforces the potential role of this supplement as a well-tolerated alternative to conventional pharmacological treatments. The current study offers a novel perspective on the potential synergy of a combined PEA, ginger, and fennel treatment, in contrast to the findings of earlier studies that investigated these compounds in isolation. This approach has the potential to offer a more effective alternative for the management of primary dysmenorrhea.

Despite these strengths, certain limitations must be acknowledged. The relatively small sample size limits the generalizability of the findings, as larger studies are needed to confirm the observed benefits. Additionally, while the study employs a randomized design, the lack of a placebo control group prevents definitive conclusions regarding the extent of the supplement's efficacy beyond potential placebo effects. Future trials incorporating a placebo arm would help strengthen the evidence base.

Another limitation is the self-reported nature of pain and symptom relief assessments. Although validated scales were used, subjective reporting is inherently prone to variability. Lastly, the study did not evaluate potential long-term effects beyond the three-month treatment period. Future research should explore the long-term impact of sustained supplementation and its comparative efficacy against standard pharmacological therapies in larger, more diverse populations.

The unfavorable consequences associated with the utilization of the alternatives identified as the gold standard for primary dysmenorrhea have prompted the exploration of novel non-pharmacological alternatives, such as the dietary supplement evaluated in this study, which has demonstrated encouraging outcomes in alleviating menstrual symptoms. It is evident that menstrual education must be provided in both a healthcare setting and to the individual patient. There are promising lines of study on non-pharmacological therapies in the treatment of primary dysmenorrhea that have the potential to reduce the reliance on pharmaceuticals and enhance the QoL for women who experience this condition. Nevertheless, further research is required in this area, and additional scientific evidence is necessary to substantiate the efficacy of these techniques.

Conclusions

A reduction in the intensity of menstrual symptoms was observed following the consumption of a supplement comprising PEA, fennel, and ginger. Furthermore, the majority of subjects reported an improvement in QoL and expressed overall satisfaction. These findings indicate that the regular consumption of the product at maintenance schedule doses lead to more favorable results. This may be attributed to the fact that the maintenance regimen formulation allows for a cumulative effect of the ingredients to be generated, which may contribute to the observed outcomes. Moreover, the implementation of this strategy may lead to a decrease in the reliance on anti-inflammatory pharmaceutical agents, which ultimately results in a decrease of the potential for adverse reactions associated with these medications.

Ethics approval and informed consent:

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards set out in the Declaration of Helsinki (1964) and in compliance with the ethical principles which apply to medical research. The study protocol was approved by the independent Ethical Committee “Comitato Etico Indipendente per le indagini Cliniche Non Farmacologiche” on December 14th 2023.

Funding:

This research was funded by Laboratorios Ordesa, SL.

Author contributions:

Rita Mocciaro was the Principal Investigator and was responsible for the conceptualization, methodology, supervision, and critical review of the manuscript. Amelia Spina contributed as a Co-investigator, being responsible for investigation, data curation, and formal analysis. Maite Pérez-Hernández participated in the critical review of the manuscript. Roser de Castellar-Sansó, as the corresponding author, contributed to the conceptualization, original draft preparation, and manuscript review and editing. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Acknowledgements:

We would like to thank the Complife Italia and Nutratech staff for their support in the study’s development, and Meisys S.A for their Medical Writing assistance.

Conflicts of interest:

MP-H and R de C-S are Laboratorios Ordesa SL, employees.

References

- Burnett M, Lemyre M. No. 345-primary dysmenorrhea consensus guideline. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 39 (2017): 585–595.

- Iacovides S, Avidon I, Baker FC. What we know about primary dysmenorrhea today: a critical review. Hum Reprod Update 21 (2015): 762-778.

- Guimarães I, Póvoa AM. Primary Dysmenorrhea: Assessment and Treatment. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 42 (2020): 501-507.

- Dawood, M.Y. Dysmenorrhea. Current Obstetrics and Gynaecology 3 (1993): 219-224.

- Burnett MA, Antao V, Black A, et al. Prevalence of primary dysmenorrhea in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 27 (2005): 765-770.

- Vicdan K, Kukner S, Dabakoglu T, et al. Demographic and epidemiologic features of female adolescents in Turkey. J Adolesc Health 18 (1996): 54-58.

- Rodrigues AC, Gala S, Neves Â, et al. Dysmenorrhea in adolescents and young adults: prevalence, related factors and limitations in daily living. Acta Med Port 24 (2011): 383-388.

- Ferries-Rowe E, Corey E, Archer JS. Primary Dysmenorrhea: Diagnosis and Therapy. Obstet Gynecol 136 (2020): 1047-1058.

- Marjoribanks J, Ayeleke RO, Farquhar C, et al. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 7 (2015): CD001751.

- Campbell MA, McGrath PJ. Use of medication by adolescents for the management of menstrual discomfort. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 151 (1997): 905-913.

- Itani R, Soubra L, Karout S, et al. Primary Dysmenorrhea: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Treatment Updates. Korean J Fam Med 43 (2022): 101-108.

- Wong CL, Farquhar C, Roberts H, et al. Oral contraceptive pill for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 4 (2009): CD002120.

- Armour M, Parry K, Al-Dabbas MA, et al. Self-care strategies and sources of knowledge on menstruation in 12,526 young women with dysmenorrhea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 14 (2019): e0220103.

- Kirsch E, Rahman S, Kerolus K, et al. Dysmenorrhea, a Narrative Review of Therapeutic Options. J Pain Res 17 (2024): 2657-2666.

- Clayton P, Hill M, Bogoda N, et al. Palmitoylethanolamide: A Natural Compound for Health Management. Int J Mol Sci 22 (2021): 5305.

- Esposito E, Cuzzocrea S. Palmitoylethanolamide in homeostatic and traumatic central nervous system injuries. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 12 (2013): 55-61.

- Nau R, Ribes S, Djukic M, et al. Strategies to increase the activity of microglia as efficient protectors of the brain against infections. Front Cell Neurosci 8 (2014): 138.

- D'Agostino G, Russo R, Avagliano C, et al. Palmitoylethanolamide protects against the amyloid-β25-35-induced learning and memory impairment in mice, an experimental model of Alzheimer disease. Neuropsychopharmacology 37 (2012): 1784-92.

- Citraro R, Russo E, Scicchitano F, et al. Antiepileptic action of N-palmitoylethanolamine through CB1 and PPAR-α receptor activation in a genetic model of absence epilepsy. Neuropharmacology 69 (2013): 115-126.

- Borrelli F, Romano B, Petrosino S, et al. Palmitoylethanolamide, a naturally occurring lipid, is an orally effective intestinal anti-inflammatory agent. Br J Pharmacol 172 (2015): 142-58.

- Petrosino S, Di Marzo V. The pharmacology of palmitoylethanolamide and first data on the therapeutic efficacy of some of its new formulations. Br J Pharmacol 174 (2017): 1349-1365.

- Tartaglia E, Armentano M, Giugliano B, et al. Effectiveness of the Association N-Palmitoylethanolamine and Transpolydatin in the Treatment of Primary Dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 28 (2015): 447-450.

- Rao A, Erickson J, Briskey D. Palmitoylethanolamide (Levagen+) for acute menstrual pain: a randomized, crossover, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Women Health (2025): 1-9.

- Gatti A, Lazzari M, Gianfelice V, et al. Palmitoylethanolamide in the treatment of chronic pain caused by different etiopathogenesis. Pain Med 13 (2012): 1121-1130.

- Briskey D, Mallard AR, Rao A. Increased Absorption of Palmitoylethanolamide Using a Novel Dispersion Technology System (LipiSperse®). J Nutraceuticals Food Sci 5 (2020): 3.

- Daily JW, Zhang X, Kim DS, et al. Efficacy of Ginger for Alleviating the Symptoms of Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials. Pain Med 16 (2015): 2243-2255.

- Yin Y, Dong Y, Vu S, et al. Structural mechanisms underlying activation of TRPV1 channels by pungent compounds in gingers. Br J Pharmacol 176 (2019): 3364-3377.

- Vyklický L, Nováková-Tousová K, Benedikt J, et al. Calcium-dependent desensitization of vanilloid receptor TRPV1: a mechanism possibly involved in analgesia induced by topical application of capsaicin. Physiol Res 3 (2008): S59-S68.

- Ozgoli G, Goli M, Moattar F. Comparison of effects of ginger, mefenamic acid, and ibuprofen on pain in women with primary dysmenorrhea. J Altern Complement Med 15 (2009): 129-132.

- Diao WR, Hua QP, Zhang H, et al. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity, and mechanism of action of essential oil from seeds of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.). Food Control 35 (2014): 109-116.

- Rafieian F, Amani R, Rezaei A, et al. Exploring fennel (Foeniculum vulgare): Composition, functional properties, potential health benefits, and safety. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 64 (2024): 6924-6941.

- Ghodsi Z, Asltoghiri M. The effect of fennel on pain quality, symptoms, and menstrual duration in primary dysmenorrhea. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 27 (2014): 283-286.

- Lee HW, Ang L, Lee MS, et al. Fennel for Reducing Pain in Primary Dysmenorrhea: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Nutrients 12 (2020): 3438.

Supplemenatry data

S1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

|

Inclusion Criteria |

|

Healthy female subjects aged between 16* and 30 years old. |

|

Reading, understanding and signed approval of the informative consent and the privacy disclaimer. |

|

Women self-reporting menstrual cramp/pain during at least four of the past six menstrual cycles. |

|

Women with no children and no history of pregnancy. |

|

Women who typically use NSAIDs (such as ibuprofen) for menstrual pain treatment. |

|

Willingness to use only the tested product and NSAIDs during the study period.** |

|

Willingness to maintain normal daily routines, including lifestyle, physical activity, diet, and fluid intake. |

|

Subjects must be registered with the National Health Service. |

|

Subjects must certify the truthfulness of the personal data provided to the investigator. |

|

Stability in pharmacological therapy (except for those in non-inclusion criteria) for at least one month, with no expected or planned changes during the study. |

|

Subjects must not have participated in any similar study within at least one month (washout period). |

|

Exclusion Criteria |

|

Acute or chronic diseases that may interfere with the study outcomes or pose a risk to the subject (including blood, cardiovascular, psychiatric, neurodegenerative diseases, diabetes, cancer, liver, gastric, skin, kidney disorders, etc.). |

|

Subjects currently participating or planning to participate in other clinical trials. |

|

Subjects deprived of freedom by administrative or legal decision or under guardianship. |

|

Subjects who cannot be contacted in case of emergency. |

|

Subjects admitted to a health or social facility. |

|

Subjects planning a hospitalization during the study. |

|

Subjects who participated in a similar study without adequate washout. |

|

Subjects under pharmacological treatments deemed incompatible with the study requirements by the investigator. |

|

Known food intolerance or food allergy. |

|

Known hypersensitivity or allergy to one of the active ingredients. |

|

Subjects who are pregnant, breastfeeding, or unwilling to take precautions to avoid pregnancy during the study (for women of childbearing potential). |

|

Consumption of food supplements with similar activity to the study product within four weeks prior to the study. |

|

Subjects suffering from eating disorders (e.g., bulimia, psychogenic eating disorders). |

|

Clinical history with a significant presence of any disorder or administration. |

*For subjects under 18, an informed consent signed by both parents was required.

**Subjects reported their NSAIDs use in the pain relief diary. NSAIDs: Non-Steroidal Anti Inflammatory Drugs

S2:

|

n |

Mean (SD) |

IC 95% |

Range (Min, Max) |

Median (IQR) |

p |

|

|

Rescue group |

||||||

|

Baseline |

28 |

5.86 (1.4) |

(5.3,6.4) |

(3.0,9.0) |

6.0 (5.0,7.0) |

|

|

T1 |

28 |

2.21 (1.3) |

(1.7,2.7) |

(1.0,5.0) |

2.0 (1.0,3.0) |

|

|

T2 |

28 |

2.54 (1.4) |

(2.0,3.1) |

(1.0,6.0) |

2.0 (1.0,4.0) |

|

|

T3 |

28 |

2.18 (1.2) |

(1.7,2.6) |

(1.0,5.0) |

2.0 (1.0,3.0) |

|

|

Change from baseline |

||||||

|

T1 |

28 |

-3.64 (1.2) |

(-4.1,-3.2) |

(-6.0,-1.0) |

-3.5 (-5.0,-3.0) |

<.001 |

|

T2 |

28 |

-3.32 (1.5) |

(-3.9,-2.8) |

(-5.0,0.0) |

-3.5 (-4.5,-2.5) |

<.001 |

|

T3 |

28 |

-3.68 (1.3) |

(-4.2,-3.2) |

(-5.0,2.0) |

-4.0 (-4.0,-3.0) |

<.001 |

|

Maintenance group |

||||||

|

Baseline |

27 |

5.59 (1.2) |

(5.1,6.1) |

(3.0,8.0) |

6.0 (5.0,6.0) |

|

|

T1 |

27 |

3.00 (1.8) |

(2.3,3.7) |

(0.0,6.0) |

3.0 (1.0,5.0) |

|

|

T2 |

27 |

2.44 (1.7) |

(1.8,3.1) |

(0.0,7.0) |

2.0 (1.0,3.0) |

|

|

T3 |

27 |

2.15 (1.7) |

(1.5,2.8) |

(0.0,7.0) |

2.0 (1.0,3.0) |

|

|

Change from baseline |

||||||

|

T1 |

27 |

-2.59 (1.5) |

(-3.2,-2.0) |

(-6.0,1.0) |

-3.0 (-4.0,-2.0) |

<.001 |

|

T2 |

27 |

-3.15 (1.7) |

(-3.8,-2.5) |

(-6.0,1.0) |

-4.0 (-4.0,-2.0) |

<.001 |

|

T3 |

27 |

-3.44 (1.7) |

(-4.1,-2.8) |

(-6.0,1.0) |

-4.0 (-4.0,-3.0) |

<.001 |

Impact Factor: * 3.2

Impact Factor: * 3.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.63%

Acceptance Rate: 76.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks