Exogenous FSH overrides age-related elevated FSH and can enforce multiple follicle growth in women undergoing IUI, a randomized controlled trial

Tamar Konig1,2*, Lisette van der Houwen3, Sjanneke Beutler4; Annelies Overbeek5; Marja-Liisa Hendriks6, Cornelis Lambalk7

1Haaglanden medisch centrum (HMC), Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The Hague, the Netherlands/

2Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc, division rReproductive mMedicine, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

3Radboud University Medical Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nijmegen, the Netherlands.

4Fertisuisse, fertility center, Olten, Switzerland

5Northwest Clinics, Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Alkmaar, The Netherlands

6Amsterdam UMC, division of General Practise, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

7Amsterdam Reproduction and Development Research Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

*Corresponding authors: Tamar Konig, Haaglanden medisch centrum (HMC), the Hague/ Amsterdam UMC, location VUmc, division Reproductive Medicine, Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

Received: 24 December 2025; Accepted: 05 January 2026; Published: 13 January 2026

Article Information

Citation:

Tamar Konig, Lisette van der Houwen, Sjanneke Beutler, Annelies Overbeek, Marja-Liisa Hendriks, Cornelis Lambalk. Exogenous FSH overrides age-related elevated FSH and can enforce multiple follicle growth in women undergoing IUI, a randomized controlled trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 9 (2026): 01-08.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Purpose:

To determine whether recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone (r-FSH) increases multifollicular development versus natural-cycle management in women with elevated basal FSH (b-FSH) undergoing intrauterine insemination (IUI), and to evaluate predictors (cycle-start FSH, anti-Müllerian hormone [AMH], antral follicle count [AFC], and FSH-receptor polymorphism).

Methods:

Open-label randomized controlled trial at a university center including 48 women allocated to a natural group (n=23; three natural then three stimulated cycles) or a stimulated group (n=25; six stimulated cycles). Stimulated cycles began with 150 IU/day r-FSH, with 75-IU increments in subsequent cycles if multifollicular growth did not occur. The primary outcome was multifollicular growth (≥2 follicles ≥14 mm on hCG day).

Results:

Baseline characteristics were comparable. The stimulated group had a 2.7-fold higher likelihood of multifollicular growth than the natural group (95% CI 1.16–6.11; P=0.02). Lower cycle-start FSH predicted multifollicular growth (odds ratio per IU/L 0.81; 95% CI 0.72–0.91; P=0.0003). Among women with detectable AMH, mean AMH was 0.68 μg/L (natural) and 0.44 μg/L (stimulated). AMH was undetectable in five women. Twelve pregnancies occurred with AMH ≤0.5 μg/L; one pregnancy occurred despite undetectable AMH.

Conclusions:

In women with elevated b-FSH undergoing IUI, r-FSH stimulation increases the probability of multifollicular growth. Controlled ovarian stimulation should be to maximize multifollicular development and potentially ongoing pregnancy. Extremely low or undetectable AMH does not preclude conception and should not alone justify denial of treatment.

The trial was retrospectively registered in the Dutch trial register (ISRCTN14825568) on 13-12-2005.

Keywords

Multifollicular growth; Controlled ovarian stimulation; Anti‑Müllerian hormone; FSH receptor polymorphism; Intrauterine insemination; Recombinant follicle‑stimulating hormone.

Article Details

Introduction:

Female reproductive ageing is a process dominated by the gradual decline of both oocyte quantity and quality [1]. The progressive follicle decline is accompanied by changes in menstrual cycle regularity [2]. A decrease in early cycle inhibin B and in anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels occurs before cycle irregularity marks the onset of the perimenopausal transition [3-4]. The decline in inhibin B results in an increase in early follicular follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) levels. The literature reflects a range of terminology used to describe a reduced ovarian reserve, alongside differing criteria and threshold values for ovarian reserve tests. In clinical practice, baseline early follicular serum FSH level is the most commonly used test to diagnose diminished ovarian reserve [5]. Women with an elevated basal FSH are often considered to be poor responders to ovarian stimulation [6]. Although several studies debate the predictive value of FSH in a subfertile population in terms of pregnancy outcome, a relationship has been found between elevated FSH and poor ovarian response in assisted reproductive technology (ART) [5, 7]. Due to this lack of uniformity in definitions and diagnostic cut-offs, the true incidence of reduced ovarian reserve among women attempting to conceive remains uncertain.

In women diagnosed with an idiopathic reduced ovarian reserve, initiating treatment directly with IVF has been proposed as a way to potentially reduce the time to pregnancy. Nevertheless, some clinicians choose to start a treatment with intrauterine insemination combined with ovarian stimulation, given the anticipated poor ovarian response associated with IVF in this group [8]. In the Netherlands IUI is a common first-line treatment for infertility in women having at least one patent tube and their partner’s sperm is of sufficient quality for IUI treatment. Patients with mild male factors, unknown causes, one sided tubal patency are usually treated with IUI before IVF treatment. Both IUI and treatment with exogenous FSH significantly improve fecundity. In couples with unexplained subfertility, IUI with ovarian stimulation results in significantly higher pregnancy rates when compared to IUI in a natural cycle (odds ratio (OR) 2.3, 95% CI 1.5-3.7). It is thought that this is the result of reaching multifollicular growth in stimulated cycles [9]. van Rumste et al. showed an absolute pregnancy rate of 8.4% with monofollicular growth versus 15% with multifollicular growth (pooled OR for pregnancy after two mature follicles compared to monofollicular growth was 1.6 [99% CI 1.3-2.0]). The risk difference (RD) was 0.05 (99% CI 0.03-0.06), indicating that the pregnancy rate increased by 5% in the multifollicular cycle compared to monofollicular growth [10].

In women with a diminished ovarian reserve multifollicular growth is often observed in a natural i.e. non stimulated cycle, as a result of elevated basal FSH levels [11]. However, to date it remains unclear whether administration of exogenous FSH will lead to additional multifollicular growth in women with elevated basal FSH and subsequently improve pregnancy rates. Therefore, the aim of this study was to examine whether exogenous FSH enhances multifollicular growth in women with already elevated basal FSH levels. Furthermore we investigated the predictive value of measurements like FSH, anti-müllerian hormone (AMH), antral follicle count (AFC) and FSH receptor polymorphism on the occurrence of multifollicular growth.

Methods

Participants

In this randomized controlled trial infertile couples with an indication for IUI treatment based on mild male factor, cervical factor or unexplained subfertility for at least one year were recruited at the VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam. They are routinely screened on day 2-4 of the menstrual cycle for their FSH levels.

Participants were required to meet the following inclusion criteria: (1) an elevated basal FSH of more then 10 IU/L measured on cycle day 2-4 (STRAW 2001); (2) age between 18 and 41 years; (3) a regular ovulatory menstrual cycle varying between 25 and 35 days;

(4) patent fallopian tubes diagnosed by hysterosalpingography; (5) yield of at least 2.0 million motile spermatozoa after semen processing. An ovulatory cycle was determined by a biphasic basal temperature chart or a midluteal progesterone level above 30 ng/L.

Exclusion criteria were (1) untreated endocrinological conditions (eg. thyroid dysfunction or hyperprolactinemia); (2) abnormal vaginal bleeding of unknown origin; (3) contra-indications for the use of r-FSH or hCG; (4) a congenital uterine anomaly or (5) external endometriosis more than grade II (ASRM score).

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board and by the medical ethical committee of the VU University Medical Center. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The trial was retrospectively registered in the Dutch trial register (ISRCTN14825568).

Study design

Women were randomized into two groups. Randomization was performed by computer and the randomly generated numbers were put into sealed opaque envelopes. Because of the apparent design differences in treatment between the two groups, the study was designed as an open-label study.

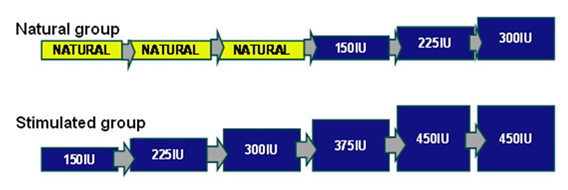

Group 1, further referred to as the “natural group”, was treated with IUI in 3 natural cycles followed by IUI in maximally three stimulated cycles. The starting dose in the first stimulated cycle (cycle four) was 150 IU recombinant FSH (r-FSH) per day. If no multifollicular growth occurred during this stimulated cycle, the dose was increased during the following cycle by 75 IU r-FSH up to a maximum daily dose of 300 IU r- FSH (Figure 1). This was the standard treatment in our center for patients starting with IUI.

Group 2, further referred to as the “stimulated group” received IUI in six subsequent stimulated cycles.

The starting dose in the first stimulated cycle was 150 IU recombinant FSH (r-FSH) per day i.e. cycle 4 in the natural group. If no multifollicular growth occurred during this stimulated cycle, the dose was increased during the following cycle by 75 IU r-FSH up to a maximum daily dose of 450 IU r-FSH (Figure 1).

Natural group: IUI in 3 natural cycles followed by IUI in 3 stimulated cycles.

Stimulated group: IUI in 6 stimulated cycles. Starting dose 150 IU r-FSH/day; if no multifollicular growth occurred, increase by 75 IU r-FSH up to 450 IU/day.

Yellow boxes: natural cycles. Blue boxes: stimulated cycles

In both groups the IUI cycle was monitored by ultrasound. On cycle day 2-4 an ultrasound was done to perform an antral follicle count (AFC) and screen for ovarian cysts and blood samples were taken for measurement of basal FSH. Additionally, at baseline a blood sample was taken for the measurement of anti-müllerian hormone (AMH). When one follicle reached 18 mm in diameter 10.000 IU hCG was administered subcutaneously and 34 to 36 hours later IUI was performed.

The primary endpoint of the study was multifollicular growth defined as ≥2 follicles ≥14 mm on the day of hCG administration. Secondary endpoints were ongoing pregnancy rate, defined as an intact intrauterine pregnancy confirmed by ultrasound after 12 weeks of gestation, cancellation rate and time needed to achieve multifollicular growth.

Laboratory assays

FSH concentrations were measured with an immunometric assay (Amerlite, Amersham, UK). The assay was calibrated against the second International Reference Preparation for FSH (78/549). The intra- and inter-assay coefficients of variation were 9 and 8% for FSH values < 25 IU/l, respectively. Estradiol concentrations were measured with a competitive immunoassay (Amerlite, Amersham, UK), with intra- and inter-assay coefficient of variation of 13 and 11% respectively for estradiol concentrations < 500 pmol/l. All samples were run in duplicate and the average values were used in the analysis.

AMH: An ultrasensitive immunoenzymometric assay kit (Diagnostic Systems Laboratories, Webster, TX, USA) was used for estimation of AMH [12]. The limit of detection (defined as blank + 3SD of blank) was

0.08 µg/L. Intra and interassay coefficients of variation were < 5%.

To define FSH receptor genotype DNA was isolated from EDTA blood samples using the FlexiGene DNA extraction kit (Qiagen, Germany). PCR amplification of the two DNA portions containing single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) at nucleotide positions 919 and 2038 within exon 10 of the FSHreceptor (FSHR) gene were performed according to Gromoll et al. [14]. The detection of the SNP distribution was conducted using an allelic discrimination assay based on TaqMan technology [15]. Homozygous controls for each of the polymorphisms were included in each run.

Transvaginal ultrasound

Transvaginal ultrasound measurements were performed using a 7.5 MHz Transvaginal probe (Aloka SSD- 3500). Follicle size was assessed by taking the mean of three perpendicular measurements. Antral follicle count was calculated by counting the follicles with a diameter of 2-10mm in both ovaries.

Statistical analysis

Statistical tests were carried out using the SPSS software package version 15.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, Illinois). We performed Student’s t-test and Chi-square tests. When the expected count was < 5 per cell Fisher’s exact test was used for the 2x2 tables. Longitudinal analysis (mixed model) was performed with correction for number of cycle and group. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

The primary endpoint of the study was development of multifollicular growth defined as ≥2 follicles ≥14 mm on the day of hCG administration. We assumed that without exogenous FSH, 5% of women would have multifollicular growth, whereas with exogenous FSH this percentage would become 30%. With an α

0.05 and a β of 0.2 the power of the study was calculated on 35 patients per group. Analysis was done by intention to treat. In each individual case the study ended in case of an ongoing pregnancy or when 6 cycles of IUI were completed. As the design of the study was not blinded it became increasingly apparent that considerably more women treated with exogenous FSH developed multifollicular growth. Out of ethical considerations we decided to permit an early closure of the study.

Results

Baseline characteristics

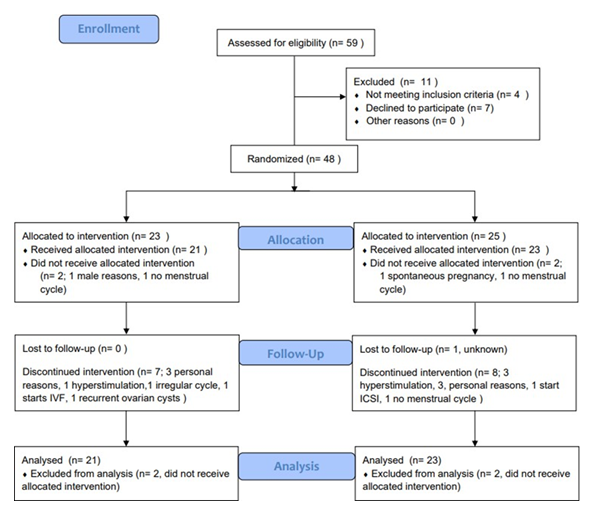

Following randomization, 48 women were included, 23 in the natural group and 25 in the stimulated group (Figure 2). Two patients in each group did not comply with inclusion criteria after randomization and where therefore excluded from analysis.

Eighteen patients did not complete the full study: 9 in the natural group and 9 in the stimulated group. Reasons for drop out are listed in figure 2. Table 1 shows the baseline characteristics. There were no statistical differences between the two groups.

|

Natural group N=23 |

Stimulated group N=25 |

|

|

Age (years) |

36.5 ± 4.2 SD |

36.3 ± 4.2 SD |

|

BMI |

24.4 ± 6.3 SD |

22.8 ± 3.0 SD |

|

Parity |

||

|

0 |

18 |

17 |

|

1 |

4 |

7 |

|

2 |

1 |

0 |

|

3 |

0 |

1 |

|

Time of infertility (months) |

29.1 ± 18.6 SD |

29.6 ± 19.0 SD |

|

Cycle length (days) |

27.7 ± 1.7 SD |

27.7 ± 1.4 SD |

|

Total sperm count (x 106) |

273.8 ± 214.6 SD |

195.0 ± 121.7 SD |

|

AFC (total) |

6.2 ± 3.7 SD |

5.7 ± 3.1 SD |

|

Day 3 FSH (IU/L) |

16.0 ± 5.1 SD |

17.2 ± 6.3 SD |

|

Indication for IUI |

||

|

Idiopathic |

18 |

19 |

|

Male factor |

4 |

5 |

|

Cervical factor |

1 |

1 |

|

FSH receptor |

||

|

NN |

8 |

6 |

|

NS |

9 |

14 |

|

SS |

6 |

5 |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of couples divided by treatment group. There were no statistical differences found between the two groups.

SD = standard deviation. BMI = body mass index. AFC = antral follicle count. FSH = follicle stimulating hormone. IUI = intra-uterine insemination. FSH receptor = Follicle stimulating hormone receptor. NN = homozygous asparagine receptor variant. NS = heterozygous asparagine serine receptor variant. SS = monozygous serine receptor variant

Occurrence of multifollicular growth

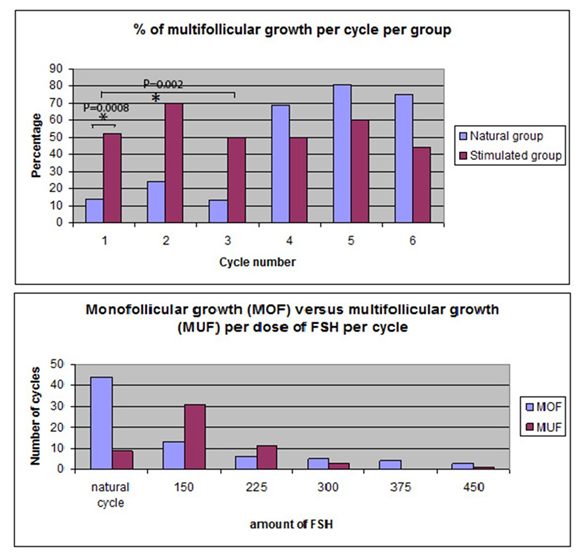

Figure 3 shows the percentage of multifollicular growth per cycle for the natural group and the stimulated group. In the first natural cycle 14% (3 of 21) of the women showed multiple follicle growth versus 52% (12 of 23 women) in the first stimulated cycle (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 - 15.77, P = 0.008).

Evaluating more than one cycle (up to a maximum of 3 cycles) 38% (8/21) of those treated with IUI in the natural cycle had multiple follicle growth at least once compared with 83% (19/23) undergoing a stimulated cycle (95% CI 1.04 - 120.36, P = 0.002).

All women (n = 8) that did not have multifollicular growth in any of 3 subsequent natural cycles showed multifollicular growth in one or more subsequent stimulated cycles. Cox regression analysis showed a hazard ratio of 2.7 for multifollicular growth in the stimulated group compared with the spontaneous group (95% CI, 1.16-6.11, P=0.02).

In the natural group, during the first three natural cycles 17% (9/53) showed multifollicular growth. 70% of these patients showed multifollicular growth in cycle 4 (with 150 IU r-FSH) (16/23) and 8 of the remaining 9 women showed multifollicular growth in cycle 5 with 225 IU r-FSH). Figure 2 shows that most women showed multifollicular growth in a stimulated cycle with either 150 IU r-FSH or 225 IU r-FSH.

With univariate analysis patients with a lower level of FSH in the beginning of a treatment cycle and/or a higher AFC were significantly more likely to have multifollicular growth in that cycle. In a multivariate analysis including age, b-FSH and AMH, only a low FSH level just before a treatment cycle remained predictive of multifollicular growth (OR of 0.81, SE 0.06, 95% CI 0.72-0.91, P=0.0003) (Table 2).

|

Univariate analysis |

Multivariate analysis |

|

|

FSH ↓ |

+ |

+ |

|

AFC ↑ |

+ |

- |

|

AMH ↑ |

- |

- |

|

Basal FSH |

- |

- |

|

Age |

- |

- |

|

FSH receptor variant |

- |

- |

Table 2: Factors that significantly predict the occurrence of multifollicular growth during IUI treatment in the first cycle (natural cycle N=21, stimulated cycle N=23)

FSH = level of follicle stimulating hormone during day 2-4 of the treatment cycle. AFC = antral follicle count. AMH = anti-müllarian hormone. basal FSH = level of follicle stimulating hormone during day 2-4 of the menstrual cycle at the time of inclusion for this study.

AMH

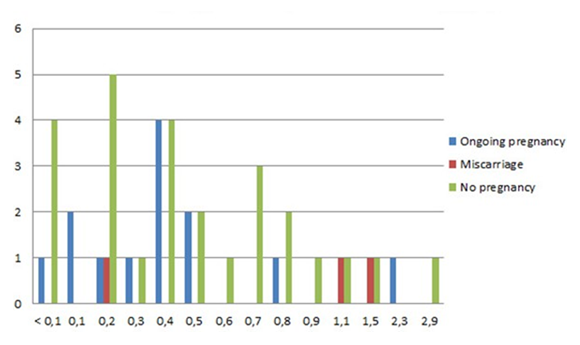

In case of a detectable AMH level, the mean in the natural group was 0.68 µg/L (range 0.1 - 2.9 µg/L) and

0.44 µg/L in the stimulated group (range 0.1 - 1.5 µg/L). In five women, AMH levels in serum were undetectable. Twelve pregnancies occurred in women with an AMH level ≤ 0.5 µg/L, one pregnancy resulted in a fetal loss before 12 weeks of gestation. One pregnancy occurred while the AMH level was undetectable (Figure 4).

Pregnancies

The number of pregnancies per group per cycle is shown in Figure 5. There was no significant difference in the number of pregnancies between the two groups. Most pregnancies occurred during a stimulated cycle therefore after 3 cycles most pregnant women were in the group that started with stimulation. After 6 cycles the number of pregnancies did not differ between the groups. 10 out of 13 ongoing pregnancies occurred during a stimulated cycle of which all 10 women had multifollicular growth. There

were 11 ongoing pregnancies in 96 multifollicular cycles (11.4%) compared to 2 pregnancies in 87 monofollicular cycles (2.3%).

Figure 5: Number of ongoing pregnancies per cycle by group; in the natural group most pregnancies occurred in cycles 4-6 (first 3 stimulated cycles), whereas in the stimulated group most pregnancies occurred in the first 3 stimulated cycles.

Discussion

This study shows that stimulation with exogenous r-FSH in women with already elevated basal FSH levels results in a remarkably higher occurrence of multifollicular growth. Furthermore our longitudinal analysis showed that patients with a lower level of FSH at the beginning of a treatment cycle and those with a higher AFC were more likely to have multifollicular growth. All women who showed monofollicular growth in natural cycles became multifollicular when treated with exogenous r-FSH.

Patients with diminished ovarian reserve represent one of the difficult subgroups of infertility patients to treat. De Koning et al., demonstrated that in women with low ovarian reserve, the intercycle variability of FSH is high. They suggest that when basal FSH normalizes this might predict the presence of a temporary larger follicle cohort [16]. When endogenous FSH is relatively lower when stimulation is used, it can overshoot the threshold for follicular development and multifollicular growth occurs [17]. In our study, incremental r-FSH dose increases when no multiple follicle growth had occurred in the previous cycle was effective up to a dosage of 225 IU. No further increase in the number of multifollicular cycles occurred if the r-FSH dose was increased to 300, 375 or 450 IU. An observation in line with this is by Klinkert et al showing in IVF patients that when AFC is below five, doubling the starting dose of FSH does not influence ovarian response and pregnancy rates in patients undergoing IVF treatment [18].

Many papers have already discussed the limitations of the various available ovarian reserve tests, including FSH in subfertile patients on prediction of an ongoing pregnancy [19]. AMH is said to be a more accurate predictor of follicle pool depletion in young women with elevated FSH [20]. In our study population, a higher AMH value was not a predictor for the occurrence of multifollicular growth. However, the mean AMH value in our study population was 0.57 µg/L, which approximates the value defined as premature ovarian failure (POI): 0.33 µg/mL [20]. In this cohort of women with unfavourable pregnancy prospects due to an elevated FSH level and low mean AMH levels, 13 pregnancies occurred in women with low (≤0.5 µg/L) or undetectable AMH levels. Therefore denial of treatment does not seem to be justified for these women, consistent with earlier reports [21-22].

Some studies have demonstrated a relation between the FSH receptor 680polymorphism and basal FSH levels. The SSvariant is thought to be less sensitive to FSH, thus leading to elevated levels of FSH in women harbouring this variant [23]. Therefore, theoretically in some women with elevated basal FSH, a less sensitive FSH receptor rather than limited ovarian reserve was present. Hence it is plausible that multifollicular growth is more likely to occur in women with an SSvariant when stimulated with exogenous FSH than in women with a limited ovarian reserve. Our study did not support this theory. The distribution of FSH receptors in our group did not differ from a general population of couples treated for infertility: 29% NN, 48% NS and 23% SS [24-25]. In our study the FSH receptor type did not relate to the occurrence of multifollicular growth upon ovarian stimulation.

There is evidence that multifollicular growth in IUI is associated with higher pregnancy rates [9-10]. Aim of our study was to answer the fundamental question whether in expected poor responders with their elevated FSH at least more often multiple follicle growth could be established by administration of even more FSH. Something what on theoretical basis could be questioned. A logical next question with more clinical implications, of course, is if this strategy could lead to more pregnancies provided that indeed multiple follicle growth could be induced more often. Based on our current study, we can only say that the overall pregnancy rate was substantial, and remarkable, most ongoing pregnancies occurring in cycles with multifollicular growth, which would confirm a similar positive effect as in women without indications for limited ovarian reserve. Given those observations our findings serve as support for a future trial investigating the same strategy with pregnancy as the primary endpoint.

Conclusions

We conclude that a stimulated cycle results in significantly more cycles with multifollicular growth and hence has the potential to promote ongoing pregnancy (11.4 vs 2.3% in a natural cycle) in subfertile women with an endogenous elevated basal FSH undergoing IUI treatment. IUI in a stimulated cycle should be considered an option in women with signs of diminished ovarian reserve and at least one patent tube and in case of normal semen parameters. Extremely low or undetectable AMH does not seem to preclude conception and should not alone justify denial of treatment.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not- for-profit sector.

Acknowledgements

Study medication was provided by Merck Serono S.A.- Geneva, Switzerland.

Conflict of interest

There is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

References

- Te Velde ER, Pearson PL. The variability of female reproductive ageing. Hum Reprod Update 8 (2002): 141-154.

- Hansen KR, Knowlton NS, Thyer AC, et al. A new model of reproductive aging: the decline in ovarian nongrowing follicle number from birth to menopause. Hum Reprod 23 (2008): 699-708.

- Burger HG, Hale GE, Robertson DM, et al. A review of hormonal changes during the menopausal transition: focus on findings from the Melbourne Women’s Midlife Health Project. Hum Reprod Update 13 (2007): 559-565.

- Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al.; STRAW+10 Collaborative Group. Executive summary of the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop +10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 97 (2012): 1159-1168.

- Broer SL, van Disseldorp J, Broeze KA, et al. Added value of ovarian reserve testing on patient characteristics in the prediction of ovarian response and ongoing pregnancy: an individual patient data approach. Hum Reprod Update 19 (2013): 26-36.

- Toner JP, Philput CB, Jones GS, et al. Basal folliclestimulating hormone level is a better predictor of in vitro fertilization performance than age. Fertil Steril 55 (1991): 784-791.

- Broekmans FJ, Kwee J, Hendriks DJ, et al. A systematic review of tests predicting ovarian reserve and IVF outcome. Hum Reprod Update 12 (2006): 685-718.

- Deneer JJM, le Cessie S, van Santbrink EJP, et al. Higher pregnancy success rates in patients with diminished ovarian reserve <40 years when initially treated by intrauterine insemination with mild ovarian stimulation compared to in vitro fertilization alone: a pilot study. Reprod Sci 32 (2025): 2010-2018.

- ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. Intrauterine insemination. Hum Reprod Update 15 (2009): 265-277.

- van Rumste MME, Custers IM, van der Veen F, et al. The influence of the number of follicles on pregnancy rates in intrauterine insemination with ovarian stimulation: a metaanalysis. Hum Reprod Update 14 (2008): 563-570.

- Beemsterboer SN, Homburg R, Gorter NA, et al. The paradox of declining fertility but increasing twinning rates with advancing maternal age. Hum Reprod 21 (2006): 1531-1532.

- AlQahtani A, Muttukrishna S, Appasamy M, et al. Development of a sensitive enzyme immunoassay for antiMüllerian hormone and the evaluation of potential clinical applications in males and females. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 63 (2005): 267-273.

- Blumenfeld Z, Halachmi S, Peretz BA, et al. Premature ovarian failure—the prognostic application of autoimmunity on conception after ovulation induction. Fertil Steril 59 (1993): 750-755.

- Gromoll J, Bröcker M, Derwahl M, et al. Detection of mutations in glycoprotein hormone receptors. Methods 21 (2000): 83-97.

- Simoni M, Nieschlag E, Gromoll J. Isoforms and single nucleotide polymorphisms of the FSH receptor gene: implications for human reproduction. Hum Reprod Update 8 (2002): 413-421.

- de Koning CH, McDonnell J, Themmen APN, et al. The endocrine and follicular growth dynamics throughout the menstrual cycle in women with consistently or variably elevated early follicular phase FSH compared with controls. Hum Reprod 23 (2008): 1416-1423.

- de Koning CH, Schoemaker J, Lambalk CB. Estimation of the folliclestimulating hormone (FSH) threshold for initiating the final stages of follicular development in women with elevated FSH levels in the early follicular phase. Fertil Steril 82 (2004): 650-653.

- Klinkert ER, Broekmans FJ, Looman CWN, et al. Expected poor responders on the basis of an antral follicle count do not benefit from a higher starting dose of gonadotrophins in IVF treatment: a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod 20 (2005): 611-615.

- van Rooij IA, Broekmans FJ, Hunault CC, et al. Use of ovarian reserve tests for the prediction of ongoing pregnancy in couples with unexplained or mild male infertility. Reprod Biomed Online 12 (2006): 182-190.

- Knauff EAH, Eijkemans MJC, Lambalk CB, et al. AntiMüllerian hormone, inhibin B, and antral follicle count in young women with ovarian failure. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94 (2009): 786-792.

- Weghofer A, Dietrich W, Barad DH, et al. Live birth chances in women with extremely lowserum antiMüllerian hormone levels. Hum Reprod 26 (2011): 1905-1909.

- Fraisse T, Ibecheole V, Streuli I, et al. Undetectable serum antiMüllerian hormone levels and occurrence of ongoing pregnancy. Fertil Steril 89 (2008): 723.e9-723.e11.

- de Koning CH, Benjamins T, Harms P, et al. The distribution of FSH receptor isoforms is related to basal FSH levels in subfertile women with normal menstrual cycles. Hum Reprod 21 (2006): 443-446.

- Kuijper EAM, Blankenstein MA, Luttikhof LJE, et al. Frequency distribution of polymorphisms in the FSH receptor gene in infertility patients of different ethnicity. Reprod Biomed Online. 2010; 21 (2010): 588-593.

- Perez MM, Gromoll J, Behre HM, Gassner C, Nieschlag E, Simoni M. Ovarian response to folliclestimulating hormone (FSH) stimulation depends on the FSH receptor genotype. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85 (2000): 3365-3369.

Impact Factor: * 3.2

Impact Factor: * 3.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.63%

Acceptance Rate: 76.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks