Is Dienogest More Effective Than Ethinylestradiol/Dienogest or Desogestrel in Reducing Ovarian Endometrioma Size? A Sonographic Retrospective Cohort Study

De Cicco Nardone Carlo1, Sangiovanni Maria Cristina1*, De Luca Cristiana1, Plotti Francesco, Montera Roberto1, Luvero Daniela1, Martinelli Arianna1, Sangiovanni Gian Mario2, Angioli Roberto1, Terranova Corrado1

1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital, Rome, Italy

2Department of Statistical Sciences, Sapienza University of Rome, Rome, Italy

*Corresponding authors: Sangiovanni Maria Cristina, Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Campus Bio-Medico University Hospital, Rome, Italy

Received: 16 December 2025; Accepted: 24 December 2025; Published: 14 January 2026

Article Information

Citation: De Cicco Nardone Carlo, Sangiovanni Maria Cristina, De Luca Cristiana, Plotti Francesco, Montera Roberto, Luvero Daniela, Martinelli Arianna, Sangiovanni Gian Mario, Angioli Roberto, Terranova Corrado. Is Dienogest More Effective Than Ethinylestradiol/Dienogest or Desogestrel in Reducing Ovarian Endometrioma Size? A Sonographic Retrospective Cohort Study. Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 9 (2026): 09-20.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Objective:

To compare the long-term sonographic effectiveness of Dienogest (DNG)2mg, Ethinylestradiol/Dienogest (EE/DNG), and Desogestrel (DSG) 75 μg in reducing ovarian endometrioma (OMA) volume, and to evaluate their performance relative to untreated patients under active follow-up (A-FU).

Methods:

This retrospective monocentric cohort study included women aged 16–55 years with transvaginal ultrasound (TV-US)–confirmed typical OMAs. Patients received DNG, EE/DNG, DSG, or no therapy (A-FU). OMAs’ volume was calculated using the prolate ellipsoid formula at baseline and at 12 and 24 months; 36-month data were included when available. Longitudinal changes in volume were analysed using a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) with random intercepts. A secondary analysis employed log-transformed volumes to account for baseline heterogeneity.

Results:

Sixty-three patients completed at least 12 months of followup (DNG n=14; EE/DNG n=39; DSG n=28; A-FU n=10). At baseline, significant differences in age and cyst size were observed, with the DNG group presenting the largest volumes (87,488 ± 68,211 mm3). All hormonal therapies induced progressive volume reduction, while untreated OMAs tended to increase. The LMM revealed a significant time × treatment interaction for DNG at 24 months (p = 0.020*), indicating a reduction exceeding the natural trajectory despite larger initial cysts. DSG and EE/DNG showed similar downward trends but without statistical significance in absolute-volume models. In contrast, the log-transformed analysis showed that all three hormonal treatments exhibited regression, whereas the A-FU group did not.

Conclusions:

Hormonal therapy effectively reduces OMA volume, with DNG showing the strongest and statistically significant effect. When adjusted for baseline heterogeneity, DSG and EE/DNG demonstrate comparable relative efficacy. Active hormonal therapy should be preferred over observation, while treatment choice should remain individualized. Prospective multicenter studies are needed to confirm these findings.

Keywords

Dienogest; Ovarian endometrioma

Article Details

Introduction:

Endometriosis affects around 10% of reproductive-age women, as a significant cause of pelvic pain and infertility [1]. Endometriosis may be classified into three subtypes: superficial peritoneal endometriosis (SPE), ovarian endometrioma (OMA), and deep infiltrating endometriosis (DIE) [2].

OMA, known as “chocolate cysts” due to the thick dark brown appearance of the fluid contained within them [3], affect up to 44% of women with endometriosis [4], representing the most frequent manifestation of the disease. With a negative impact on ovarian reserve, the management of OMA is particularly relevant in women desiring future fertility [5]. Laparoscopic cystectomy with the stripping technique has traditionally been the first choice for conservative treatment of OMA [6,7]. Nevertheless, concerns about ovarian tissue damage, particularly the potential reduction in ovarian reserve and its negative impact on assisted reproductive outcomes, have highlighted a paradox [8] in infertile women and led to growing interest in conservative medical therapy. Medical therapy, which includes, combined oral contraceptives (COCs)- and progestin-only pills (POPs), is considered a first-line treatment to reduce endometriosis-associated pain, including dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and non-menstrual pelvic pain [9,10].

According to the ESHRE guidelines, COCs are also strongly recommended for long-term prevention of endometrioma recurrence after surgery in women not seeking immediate pregnancy [10]. However, in the literature, there is a lack of evidence regarding the effect of COC therapy on OMA diameter [9]. Among POPS, Dienogest (DNG), a fourth-generation progestin [11], is also considered effective in decreasing the size of endometrioma [12], reducing endometriosis-associated pain with a favourable safety and tolerability profile [10,13]. Moreover, Desogestrel (DSG) [14], a third-generation progestin [15] and a one of the most widely used POPs, is also considered an effective treatment for endometriosis, improving dysmenorrhea in up to 93% of cases [16]. Despite the widespread use of COCs, DNG and DSG in clinical practice, evidence on their comparative effectiveness in reducing OMA size remains inconsistent and limited. Furthermore, existing comparative studies between COCs, DNG and DSG primarily focus only on symptom control, such as pain reduction, without assessing changes in endometrioma volume [17].

To address this issue, the present retrospective cohort study evaluates changes in OMA volume when comparing DNG, ethinylestradiol/dienogest (EE/DNG) and DSG therapy.

Materials and Methods

Study Design and Setting

This retrospective monocentric cohort study was conducted in the Department of Gynaecology and Obstetrics at the University

Hospital Campus Bio-Medico of Rome between November 2018 and October 2025.

Participants

Women aged 16-55 years with a transvaginal ultrasound (TV-US) confirmed typical OMA were eligible for inclusion. Additional criteria were a BMI between 18 and 35, availability of baseline and follow-up scans, and a minimum follow-up duration of 12 months. Exclusion criteria included a history or a suspicion of malignancy in atypical OMA, ovarian surgery performed before or during the study period, pregnancy, any change in hormonal therapy, or incomplete clinical or imaging records.

Treatment Groups

Patients were divided into four groups according to the therapy received:

(A) 2 mg DNG: 1 tablet per day for 28 consecutive days, with the blister pack containing no placebo tablets.

(B) 2mg DNG/30 μg EE: 1 tablet per day for 28 consecutive days, with the blister pack of 28 tablets containing 7 placebo tablets.

(C) 75 mcg DSG: 1 tablet per day for 28 consecutive days, with the blister pack containing no placebo tablets.

(D) Active follow-up (A-FU): control group in which no treatment was administered.

Treatment duration was at least 12 months.

Clinical Evaluation and Ultrasound Assessment

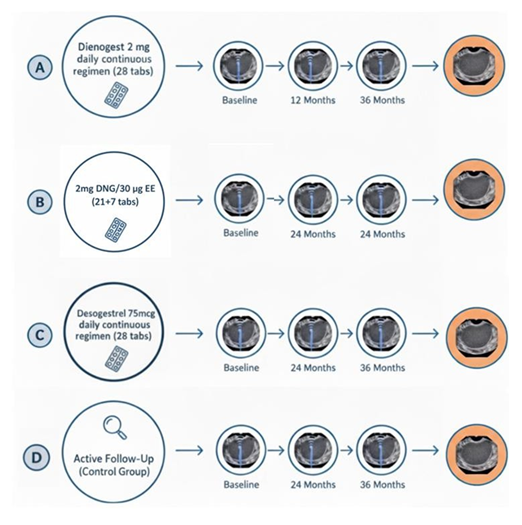

All patients underwent a standard gynaecological evaluation, including medical history, physical examination, and TV-US. Each patient underwent a baseline scan and a follow-up scan after 12 and 24 months of observation or treatment. When available, data from patients who completed a 36-month follow-up were also included, acknowledging that not all participants reached this extended timepoint. A schematic overview of the study design and follow-up schedule is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Study design and TV-US follow-up timeline. Patients were divided into three groups: (A) continuous dienogest 2 mg (28-day regimen without placebo); (B) combined ethinylestradiol 30 μg + dienogest 2 mg (21 active + 7 placebo tablets); (C) continuous Desorgestrel 75 mcg (28-day regimen without placebo); D active follow-up (without medical treatment). Participants underwent TV-US at baseline, 12 and 24 months to assess endometrioma size. Data from patients who additionally reached the 3c-month follow-up were also collected, although not all participants completed this extended time point.

For each patient, the following information was collected: type and start date of hormonal therapy, serial TV-US findings (presence, number of OMAs per patient and their three orthogonal diameters), and changes in treatment during follow-up. All TV-US examinations were performed using a GE Healthcare Voluson E8TM ultrasound system with a RIC 5-9D endovaginal probe (5-9 MHz), by the same senior sonographer with extensive expertise in endometriosis imaging.

OMAs were identified and described according to the International Society of Ultrasound in Obstetrics C Gynecology (ISUOG)18, to the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) [19]. classification and to the Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting Data System Ultrasouns (O-RADS US) [20]: Typical OMA is defined as a < 10 cm unilocular or multilocular (less than five locules) cyst with

homogeneous low-level “ground-glass’’ echogenicity of the cyst fluid, regular smooth walls with no papillary projections, and absence of vascularized solid components.

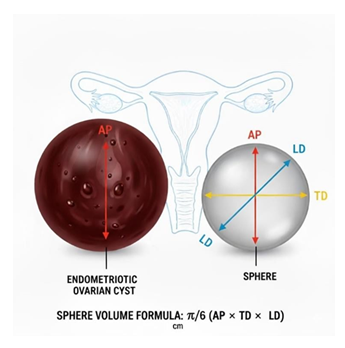

OMAs’ volume can be measured using a prolate ellipsoid formula, where the volume is calculated from the three orthogonal diameters expressed in mm (anteroposterior -AP, transverse-TD, and longitudinal- LD) using the formula π/6 (AP ×TD×LD), as shown in Figure 2. The volume of the cysts is expressed in mm³. This method provides a way to estimate the three- dimensional size of a cyst from bidimensional TV-US measurements.

Figure 2: Schematic representation of the method used to estimate endometrioma volume. The three orthogonal diameters—anteroposterior (AP), transverse (TD), and longitudinal (LD)—are measured on transvaginal ultrasound and used to approximate cyst volume with the ellipsoid formula: π/c × (AP × TD × LD). The illustration compares an endometriotic ovarian cyst with a reference sphere to visualise the dimensional assessment.

Outcomes

The analysis aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of different hormonal treatments in reducing endometrioma size by comparing mean volume changes across treatment groups and against untreated controls (A-FU) at 12, and when available, 24 and 36 months. In fact, data from patients who also reached the 24- and 36-month follow-up were collected, although not all participants completed this extended time point.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (version 4.4.3). Normally distributed continuous variables (e.g., age) were compared across the four groups using one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA), while non-normally distributed variables (e.g., baseline cyst volume) were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test. Categorical variables were evaluated using Pearson’s

Chi-square test.

Given the longitudinal design of the study, in which each patient contributed repeated TV-US measurements at baseline and at 12, 24, and 36 months, a Linear Mixed-Effects Model (LMM) was employed. This approach appropriately accounts for within-subject correlation and accommodates missing data under the Missing at Random (MAR) assumption, allowing the inclusion of all patients with at least one follow-up assessment.

The primary analysis was conducted on absolute endometrioma volumes. Fixed effects included time, treatment group (DSG 75 µg, DNG 2 mg, EE/DNG, and A-FU), and their interaction to determine whether volume trajectories differed among groups. The model estimated: (i) the baseline mean volume (reference: no therapy), (ii) changes at each follow-up relative to baseline, (iii) differences between treatment groups at baseline, and (iv) time × group interactions, representing differential longitudinal responses to treatment.

The statistical significance of fixed effects was assessed using Type III ANOVA with Satterthwaite’s approximation to derive F-statistics and p-values. Random-effects variance components were examined to quantify between-subject variability. Model assumptions (normality and homoscedasticity of residuals) were verified through diagnostic plots.

All tests were two-sided, and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. A secondary analysis using log-transformed volumes [log(volume + 1)] was performed to normalize the distribution, stabilize variance, and reduce the influence of extreme baseline heterogeneity

Ethical Approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee and in adherence to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient data were anonymized; informed consent was waived due to the retrospective design.

Data Collection and Management

Data were retrieved from the institutional electronic medical record system and entered into a password-protected Excel spreadsheet, which was stored on the secure hospital server. All identifiers were removed before analysis, and only anonymized data were used for statistical evaluation.

Results

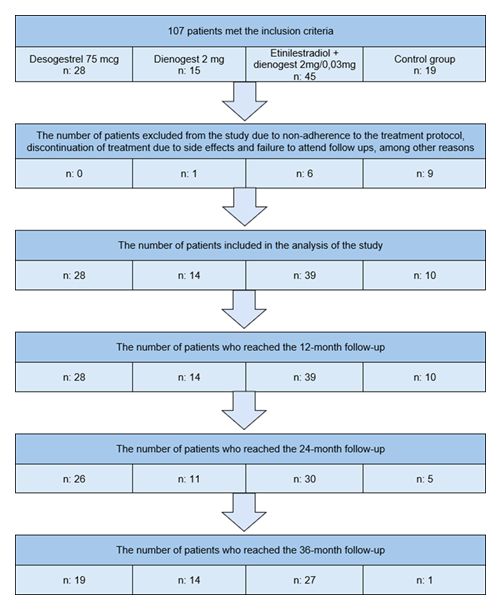

Figure 3 illustrates the study flow diagram, showing the number of patients included in each treatment group and the proportion of who completed the scheduled follow-up assessments at 12, 24, and 36 months. The initial cohort consisted of 108 women (DSG 28, DNG n = 15;EE/DNG n = 45; Control: n = 19).

After exclusions due to non-adherence, treatment discontinuation, or loss to follow-up, 91 patients remained eligible for analysis (DSG 28; DNG: n = 14; EE/DNG: n = 39; Control: n = 10), all of whom reached at least the 12-month evaluation. The number of patients available for volumetric assessment declined progressively at later time points, as detailed in Figure 3.

Table 1 summarises the baseline characteristics of the study population across the three groups. A total of 14 patients (18 cysts) were included in the DNG 2 mg group, 39 patients (54 cysts) in the EE/DNG group, and 10 patients (11 cysts) in the control group. Conversely, a statistically significant difference was observed regarding age (p = 0.026). While the treatment groups (DNG, EE/DNG, DSG) shared a similar mean age (range 35- 37 years), the Active Follow-up group was significantly older (mean 44.1 ± 8.9 years). Clinically, this imbalance is expected in observational studies: women closer to menopause (Group 4) often opt for a "wait and see" monitoring approach, whereas younger women prioritize fertility

preservation or long-term symptom control through active therapy.

|

Treatment group |

N° patients |

N° cysts analyzed |

Mean age (years) |

Mean bmi (kg/m²) |

|

Dienogest 2 mg |

14 |

18 |

37.6 ± 8.5 |

26.0 ± 2.1 |

|

EE 30 µg / DNG 2 mg |

39 |

54 |

35.9 ± 7.5 |

25.4 ± 2.3 |

|

Desogestrel 75 mcg |

28 |

35 |

36.7 ± 7.4 |

25.2 ± 2.3 |

|

Active follow up (no therapy) |

10 |

11 |

44.1 ± 8.9* |

26.5 ± 1.8 |

|

p- value |

0.026* |

0.305 |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the study population by treatment group, including the number of patients and cysts, mean age, and mean BMI.

Table 2 details the cyst multiplicity per patient. The majority of patients presented with a single endometrioma, although multiple cysts were observed, particularly in the EE/DNG and DSG group.

|

Treatment |

n° patients with 1 endometriotic cyst |

||||

|

n° patients with 2 OMA |

n° patients with 3 OMA |

n° patients with 4 OMA |

n° patients with 5 OMA |

||

|

Dienogest 2 mg |

13 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

EE 30 µg / DNG 2 mg |

27 |

10 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

|

Desogestrel 75 mcg |

21 |

7 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Active follow up (no therapy) |

9 |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

Table 2: Number of patients with one or more endometriotic cysts per treatment group. The table shows the distribution of patients according to the number of endometriotic cysts (from one to five) in each treatment arm

Table 3 summarizes the mean endometrioma volume for each group at baseline and during follow-up at 12, 24, and 36 months. At baseline (T0), a statistically significant difference in cyst size distribution was observed among the four groups, reflecting marked heterogeneity within the study population. The DNG 2 mg group had the largest mean baseline volumes, whereas the Active Follow-up (control) group had considerably smaller lesions. Despite these initial imbalances, longitudinal evaluation revealed clearly divergent volumetric trajectories across groups. All three hormonally treated cohorts showed a progressive and substantial reduction in cyst volume over time. The DNG group demonstrated the most pronounced decline, decreasing from 87,488 ± 68,211 mm³ at baseline to 1,597 ± 1,373 mm³ at 36 months. DSG and EE/DNG displayed similar trends of sustained shrinkage. In contrast, the Active Follow-up group exhibited persistence or progression of disease, with mean volumes nearly doubling during the first 12 months and remaining elevated thereafter.

|

Mean (± sd) endometrioma volume (mm³) |

||||

|

Group |

Baseline volume (t0) |

Volume at 12 months (t12) |

Volume at 24 months (t24) |

Volume at 36 months (t36) |

|

Dienogest 2 mg |

87,488 ± 68,211 |

21,071 ± 15,019 |

4,900 ± 3,693 |

1,597 ± 1,373 |

|

EE 30 µg / DNG 2 mg |

14,210 ± 3,538 |

7,578 ± 2,788 |

2,108 ± 708 |

665 ± 261 |

|

Desogestrel 75 mcg |

38,462 ± 11,764 |

10,620 ± 4,917 |

8,643 ± 3,959 |

2,910 ± 1,961 |

|

Active follow up (no therapy) |

6,008 ± 10,040 |

10,890 ± 5,286 |

NS |

NS |

|

P-value* |

0.011* |

< 0.001 |

< 0.001 |

< 0.01 |

Table 3: Mean (± SD) endometrioma volume (mm³) at baseline and at 12, 24, and 3c months in the four treatment groups. P- values refer to overall between-group comparisons at each time point. P-value calculated using Kruskal-Wallis test. NS = Not Significant.

However, cross-sectional comparisons of raw absolute volumes at 12, 24, and 36 months did not reach statistical significance (p > 0.05). This apparent lack of significance is attributable to the very large inter-subject variability and wide standard deviations observed within each group, which dilute the measurable between-group differences in simple unadjusted tests. Moreover, baseline heterogeneity—particularly the substantially larger initial cyst volumes in the DNG cohort—further limits the interpretability of cross-sectional statistics.

To appropriately address this variability and adjust for baseline imbalances, a Linear Mixed- Effects Model (LMM) was performed. The mixed-effects analysis was performed on a longitudinal dataset comprising 392 observations from 91 subjects. Variance component estimates confirmed marked between-subject heterogeneity (random intercept SD = 43,684) and substantial residual variability (residual SD = 58,194), supporting the use of subject- specific random intercepts to model repeated measures appropriately.

Table 4 reports the fixed-effect estimates. Type III ANOVA demonstrated a significant overall effect of Time (F(3, ≈304) = 5.77, p < 0.001), indicating meaningful changes in endometrioma volume across follow-up for the cohort as a whole. In contrast, the main effect of Treatment Group was not statistically significant (p = 0.374), likely reflecting the high inter-subject variability and baseline volume differences among groups.

|

Parameter |

Effect estimate (mm³) |

95% confidence interval |

P- value |

|

Time effects (ref: baseline) |

|||

|

Time: 12 months |

−20,411 |

−66,048 to +28,226 |

0.41 |

|

Time: 24 months |

−11,470 |

−76,117 to +53,178 |

0.73 |

|

Time: 36 months |

−10,810 |

−136,263 to +117,674 |

0.87 |

|

Treatment effects (relative to no control group at t0) |

|||

|

DSG 75 mcg |

+6,765 |

−41,677 to +61,508 |

0.71 |

|

DNG 2 mg |

+73,337 |

+16,563 to +130,081 |

0.01* |

|

EE/ DNG |

−10,864 |

−56,586 to +37,801 |

0.66 |

|

Significant interactions |

|||

|

DNG at 24 months |

−63,670 |

−173,002 to −14,638 |

0.02* |

Table 4: Fixed effects estimate from the Linear Mixed-Effects Model regarding endometrioma volume (mm³). Values are presented as effect estimates with corresponding S5% Confidence Intervals (CI) and p-values. The model reveals that the DNG 2 mg group had a significantly higher baseline volume compared with the control group (p = 0.01) and exhibited a significant negative interaction at 24 months (p = 0.02), indicating a greater rate of volume reduction over time relative to no therapy.

Examination of specific contrasts revealed clinically and statistically relevant differences in treatment trajectories. The DNG 2 mg group had a significantly higher estimated mean baseline volume than the Active Follow-up group (Estimate ≈ +73,337 mm³; p = 0.012). Importantly, this group exhibited a significant negative interaction at 24 months (Estimate ≈ −93,970 mm³; p = 0.020), indicating a greater reduction in cyst volume over time relative to the natural progression observed in untreated patients. Thus, despite larger initial cyst volumes, Dienogest-treated patients demonstrated a more pronounced volumetric decline.

For the DSG and EE/DNG groups, the observed reductions did not reach statistical significance compared with the control group (p > 0.05), a finding consistent with both the smaller baseline cyst dimensions in these groups and the substantial residual variance captured by the model.

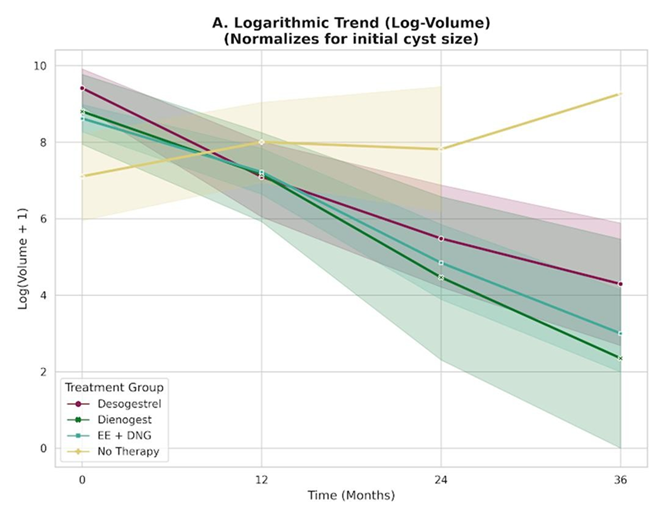

Given the marked baseline heterogeneity and high inter-subject variance demonstrated by the mixed-model analysis of absolute volumes, a secondary analysis was performed using log- transformed volumes [log(Volume + 1)]. This transformation reduces the influence of extreme values and enables a normalized comparison of treatment effects across different initial cyst sizes.

As illustrated in Figure 4A, the logarithmic trajectories showed clear divergence between treated patients and the control cohort. The Active Follow-up group displayed a flat or slightly upward trend, consistent with cyst stability or progression. In contrast, all hormonally treated groups (DSG 75 mcg, DNG 2 mg, and EE/DNG) exhibited similarly steep negative slopes, indicating a consistent rate of volume reduction over time, irrespective of baseline cyst size.

- Longitudinal trajectories of log-transformed endometrioma volumes [log(Volume + 1)], applied to normalize the marked heterogeneity in baseline cyst size. The three active treatment groups (Dienogest 2 mg, Desogestrel 75 mcg, and EE/DNG) display nearly parallel downward slopes, indicating a comparable rate of cyst regression over time. In contrast, the Active Follow-up group shows a flat or slightly upward trend, consistent with cyst stability or progression.

Statistical testing on the transformed data confirmed that all active treatments significantly outperformed the control condition. DSG demonstrated a significant reduction as early as 12 months (p = 0.006), with effects maintained at 24 months (p < 0.001). Likewise, both EE/DNG and DNG showed highly significant reductions at 24 months (p < 0.001).

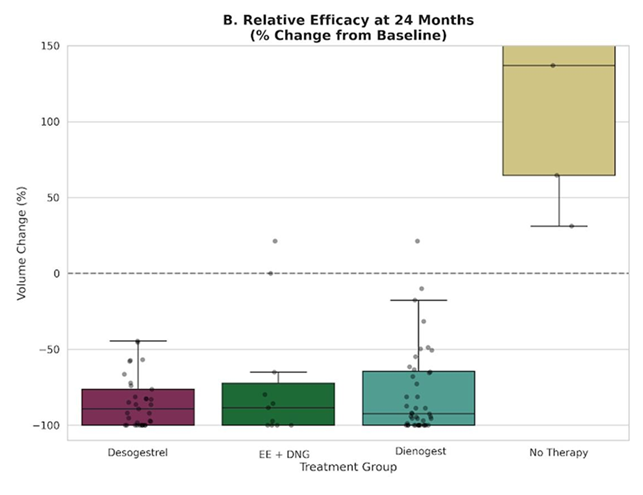

Figure 4B further highlights the relative treatment efficacy by illustrating percentage change from baseline at the 24-month endpoint. While untreated patients exhibited wide variability with a median tendency toward stability or growth, all hormonally treated patients clustered within a pattern of pronounced regression, typically approaching an 80%-100% reduction in volume. When normalized for cyst size, these findings demonstrate that DSG and EE/DNG achieve a therapeutic effect comparable to that of DNG in halting and reversing endometrioma growth.

- Relative efficacy expressed as percentage volume change at 24 months. The box plots illustrate the distribution of volume reduction relative to each patient's baseline. While the Active Follow-up group shows wide variability with a median tendency toward disease persistence (distribution centering around 0% change), all active treatment groups cluster consistently in the range of substantial regression. This confirms that, in terms of relative therapeutic impact, DSG and EE/DNG achieve a magnitude of regression comparable to DNG.

Discussions

OMAs occur in 17-44% patients with endometriosis [21]. Ovaries are the most common sites of endometriosis [22], with an interesting left lateral predisposition [23,24,25]. Vercellini et al. [26] and Sznurkowski et al. [27] attribute this left-sided predominance of OMAS to the mechanical effect of the sigmoid colon, which reduces peritoneal fluid clearance on the left side. Chapron et al. [28]. additionally suggest hormonal and microenvironmental differences between hemipelves. On the other side, Matalliotakis et al. [29] propose the “female varicocele theory,” linking left-sided venous stasis to increased susceptibility to endometrioma formation.

Traditionally, laparoscopy was considered the gold standard for the examination of endometriotic lesions [30]. Nowadays, guidelines [10] have shifted their focus to non-invasive imaging-based diagnosis of deep endometriosis in preference to surgery, with a great attention to TV-US, which should be performed in a standardised manner, as described by the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group [31].

A typical endometrioma on TV-US is described as a unilocular or multilocular (less than five locules) cyst, with homogeneous low-level echogenicity (ground glass echogenicity) of the cyst fluid. Because endometriomas are usually poorly vascularised32. Resonance Magnetic Image (RMI) for OMAs is requested only in selected cases if ultrasound outcome is inconclusive, if malignant transformation is suspected, or both [32].

The therapeutic approach to endometriosis should be individualised, considering the clinical presentation (whether pain or infertility), the patient’s age, ovarian reserve, reproductive desire, and the specific disease phenotype, including the presence of endometriomas, adenomyosis, and the overall extent of the lesions [33].

Volumetric reduction achieved through medical therapy may decrease the need for surgical intervention, thereby supporting ovarian function preservation and improving symptom control34. POPs and COCs are both well-tolerated medical treatments and represent safe, long-term, first-line therapeutic options33, 35. COCs, administered orally, transdermal or via vaginal ring, and POPs are strongly recommended for reducing endometriosis-associated dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea and non-menstrual pelvic pain [10].

Among POPs, DNG, 19-nortestosterone derivative, fourth-generation progestin, used at dosage, 2 mg per day, provides a significant local effect on endometriotic lesions and it is as first-line medical treatment for pain in endometriosis [35].

Moreover, previous studies demonstrated that DNG 2 mg/day also leads to a significant reduction in both the diameter and volume of OMAs36. After six months of therapy, mean cyst volume may decrease by approximately 66%, with reductions exceeding 76.19% after twelve months36. Recent evidence indicates that, in cysts measuring ≥4 cm, the mean diameter can decrease from around 50.5 mm to 34 mm within one year, accompanied by a marked volumetric reduction (from 37.8 mL to 11.8 mL in 12 months) [37]. DNG is also effective in reducing the size of recurrent OMAs38, while maintaining a favourable safety profile, including minimal impact on bone health39 even with treatment durations of up to one year. This is a notable advantage compared with other medical therapeutic options (such as Gonadotropin- Releasing Hormone Antagonists -GnRH- agonist and antagonist) that are associated with substantial bone loss [39].

Also COCs, and in particular 2mg DNG/30 μg EE have also been associated with a significant reduction in OMAs size, particularly when used continuously and over more extended treatment periods exceeding 6-12 months40.

From this perspective, the present study aimed to evaluate and compare the efficacy of continuous DNG, DSG and a COC containing 2 mg DNG/30 µg EE in reducing the sonographic size of OMAs.

The patient flow analysis (Figure 3) clearly outlines the study's retention profile over time. An essential limitation of the longer follow-up period must be acknowledged. The longitudinal evaluation is affected by the fact that not all patients reached the 24- and 36-month assessments. This progressive reduction in sample size (attrition rate) was particularly pronounced in the Active Follow-up group, which, already smaller at baseline compared with the active treatment arms, was substantially eroded over time, resulting in only one evaluable patient at the final follow-up. Consequently, while short-term comparisons (12 months) are reliable, interpretation of long-term trajectories, especially for the untreated group, requires caution, given the limited data available.

A significant demographic finding emerged from the baseline comparison: patient age differed among groups (p = 0.026). Women receiving hormonal therapy had comparable mean ages, whereas the Active F-U cohort was significantly older (44.1 ± 8.9 years). This discrepancy likely reflects a well-recognized observational pattern in clinical practice: perimenopausal women frequently opt for a conservative “wait-and-see” approach, avoiding hormonal treatments in anticipation of the natural decline in ovarian activity. Conversely, younger patients typically require active medical management to preserve fertility and maintain long-term symptom

control. Notably, there were no significant differences in BMI across groups, supporting anthropometric homogeneity of the sample.

Another key aspect concerns the baseline distribution of cyst volume. Patients treated with DNG 2 mg presented with substantially larger cysts at enrolment compared with all other groups, particularly the control group. This imbalance may suggest the presence of “channelling bias” [41]: DNG may be preferentially prescribed to women with more severe disease, higher symptom burden, or larger OMAs. This underscores the importance of employing statistical methods that appropriately account for significant baseline heterogeneity.

The longitudinal raw-volume trends demonstrated divergent behaviours across groups. All hormonal treatments showed progressive reductions in endometrioma volume, whereas the Active F-U group displayed stable or slightly increasing volumes over time. However, high intersubject variability and imbalanced baseline volumes limited the statistical significance of cross-sectional comparisons at each time point, despite a clear clinical signal: untreated endometriomas tend not to regress spontaneously.

The linear mixed-effects model with random intercepts represented the appropriate analytical approach to address both repeated measurements and baseline heterogeneity. The model demonstrated a significant time × treatment interaction for the DNG group at 24 months. The model showed that the volumetric decline in the DNG group diverged significantly from the natural course observed in the untreated cohort. Notably, the interaction at 24 months indicates that, despite initial disadvantage, patients receiving DNG experienced a substantially greater reduction in OMAs’ volume over time, exceeding what would be expected based on baseline size alone.

This result underscores that DNG not only reduces cyst volume but also actively modifies the trajectory of disease progression, a conclusion that could not be reliably inferred from analysis of raw absolute volumes alone.

Other treatments did not reach statistical significance in the absolute-volume model, likely because these groups started with substantially smaller cysts, which diluted the detectable statistical signal.

Overall, the log-transformed analysis effectively normalized baseline size heterogeneity and confirmed a clear therapeutic advantage of all active treatments over observation alone. Compared with the Active F-U group, which showed a flat or slightly increasing trajectory, DNG, DSG, and EE/DNG consistently exhibited a downward trend, indicating progressive and sustained reduction in OMAs’ volume. These findings reinforce the positive impact of hormonal therapy in modifying the natural history of OMAs.

The findings of this study highlight several clinically meaningful aspects of endometrioma management. In the absence of treatment, OMAs generally persist or enlarge over time, reinforcing the chronic, progressive nature of the disease. By contrast, all hormonal therapies evaluated induced substantial regression, both in absolute terms and in relative, size-adjusted analyses. DNG emerged as the treatment that produced the most pronounced effect in the adjusted longitudinal model, significantly altering the natural evolution of the cysts, despite being prescribed to patients with the largest baseline volumes. Yet, when baseline heterogeneity was normalized through log-transformed and percentage-change analyses, DSG and EE/DNG demonstrated a therapeutic impact comparable to that of DNG, suggesting that their efficacy should not be underestimated. Similar to our study, the survey conducted by Angioni et al. [34] demonstrated a greater reduction in OMAs size in patients treated with DNG alone, with mean cyst diameter decreasing from 54± 22 mm to 32 ± 12 mm after six months, a reduction corresponding to approximately 75% of cyst volume. In contrast, combined EE/DNG therapy did not result in a significant dimensional change despite symptomatic improvement, indicating that only DNG monotherapy exerted a meaningful effect on endometrioma shrinkage [34].

The present study has several strengths that contribute to its clinical relevance. It provides one of the few longitudinal evaluations comparing different hormonal regimens for ovarian endometriomas, using repeated sonographic measurements over a follow-up of up to 36 months, thereby capturing both short- and long-term therapeutic trajectories. The integration of absolute, log-transformed, and percentage-change analyses offers a nuanced interpretation of treatment efficacy, overcoming the inherent heterogeneity in baseline cyst volumes and providing a more robust representation of actual clinical effectiveness.

Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the retrospective and monocentric design introduces inherent risks of selection bias and limits the ability to account for unmeasured confounders. Second, the overall sample size remains relatively small, particularly at longer follow-up intervals due to attrition, which reduces statistical power and may affect the stability of subgroup comparisons. Third, unequal baseline characteristics between groups, especially differences in age and initial cyst volume, reflect real-world prescribing patterns and complicate direct comparisons despite statistical adjustment. Finally, the generalizability of these findings remains limited, and larger prospective multicenter studies are warranted to validate these results, refine comparative estimates of treatment effectiveness, and better guide individualized therapeutic decision-making.

Conclusions

This study provides new evidence supporting the role of hormonal therapy in the long-term conservative management of OMAs. Among the therapies evaluated, DNG 2 mg demonstrated the most pronounced therapeutic effect, achieving a statistically significant time × treatment interaction at 24 months, indicating a volumetric reduction that clearly diverged from the natural course of untreated cysts. Notably, this effect emerged despite the DNG group presenting with substantially larger cysts at baseline, suggesting that DNG is remarkably effective even in the context of advanced disease burden. These findings reinforce the drug’s

ability not merely to reduce cyst size, but to modify the trajectory of OMAs progression, a result that would not have been detectable through simple analysis of raw volumes alone.

The secondary log-transformed analysis further demonstrated that all three hormonal regimen, including DSG and EE/DNG, were superior to observation alone, showing a consistent downward trajectory of OMA’s volume regression over time. When baseline heterogeneity was normalized, DSG and EE/DNG achieved a degree of relative regression comparable to DNG, underscoring that multiple medical options can provide meaningful disease control.

Taken together, these findings confirm that active hormonal therapy should be preferred over observation in reproductive-age women with OMAs. Therapy choice, however, should remain individualized, considering patient age, reproductive goals, symptomatology, baseline cyst characteristics, and treatment tolerability.

Given the limitations inherent to the retrospective, monocentric design and the attrition observed at longer follow-up intervals, larger prospective multicenter studies are needed to validate these results, refine comparative effectiveness estimates, and guide evidence-based personalization of medical therapy for ovarian endometriomas.

References

- Taylor, H. S., Kotlyar, A. M. C Flores, V. A. Endometriosis is a chronic systemic disease: clinical challenges and novel innovations. Lancet 3G7 (2021): 839-852.

- Imperiale, L., Nisolle, M., Noël, J.-C. C Fastrez, M. Three Types of Endometriosis: Pathogenesis, Diagnosis and Treatment. State of the Art. J Clin Med 12 (2023): 994.

- Hoyle, A. T. C Puckett, Y. Endometrioma. in StatPearls (StatPearls Publishing, Treasure Island (FL), 2025).

- Billow, M., Sridhar, S. C Mintz, G. Endometrioma: Contemporary Approach to Diagnosis and Management. Semin Reprod Med https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0045-1810430 (2025).

- Perrone, U. et al. Endometrioma surgery: Hit with your best shot (But know when to stop). Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology G6 (2024): 102528.

- Bafort, C., Beebeejaun, Y., Tomassetti, C., et al. Laparoscopic surgery for endometriosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (2020): CD011031.

- Pados, G., Daniilidis, A., Keckstein, J., et al. A European survey on the conservative surgical management of endometriotic cysts on behalf of the European Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy (ESGE) Special Interest Group (SIG) on Endometriosis. Facts Views Vis Obgyn 12, 105-108.

- Dias Jr, J. A. et al. The endometrioma paradox. JBRA Assist Reprod 2G (2025): 145-149.

- Muzii, L. et al. Expectant, Medical, and Surgical Management of Ovarian Endometriomas. Journal of Clinical Medicine 12 (2023): 1858.

- Becker, C. M. et al. ESHRE guideline: endometriosis†. Hum Reprod Open 2022, hoac009.

- Schindler, A. E. Dienogest in long-term treatment of endometriosis. Int J Womens Health 3 (2011): 175-184.

- Huang, Y., Zhang, D., Zhang, L., et al. Clinical efficacy of dienogest against endometriomas with a maximum diameter of ≥4 cm. Ann Med 56 (2024): 2402942.

- Uludag, S. Z., Demirtas, E., Sahin, Y. C et al. Dienogest reduces endometrioma volume and endometriosis-related pain symptoms. J Obstet Gynaecol 41 (2021): 1246-1251.

- in Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) (National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, Bethesda (MD), 2006).

- Scala, C., Leone Roberti Maggiore, U., Remorgida, V., et al. Drug safety evaluation of desogestrel. Expert Opin Drug Saf 12 (2013): 433-444.

- Weisberg, E. C Fraser, I. S. Contraception and endometriosis: challenges, efficacy, and therapeutic importance. Open Access J Contracept 6 (2015): 105-115.

- Yurtkal, A. C Oncul, M. Comparison of dienogest or combinations with ethinylestradiol/estradiol valerate on the pain score of women with endometriosis: A prospective cohort study. Medicine (Baltimore) 103 (2024): e38585.

- Van Holsbeke, C. et al. Endometriomas: their ultrasound characteristics. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 35 (2010), 730-740.

- Cohen Ben-Meir, L., Mashiach, R. C Eisenberg, V. H. External Validation of the IOTA Classification in Women with Ovarian Masses Suspected to Be Endometrioma. Journal of Clinical Medicine 10 (2021): 2971.

- (PDF) O-RADS US Risk Stratification and Management System: A Consensus Guideline from the ACR Ovarian-Adnexal Reporting and Data System Committee. ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/publication/337045294_O- RADS_US_Risk_Stratification_and_Management_System_A_Consensus_Guideline_from_the_ACR_Ovarian-Adnexal_Reporting_and_Data_System_Committee (2018).

- Gałczyński, K., Jóźwik, M., Lewkowicz, D., et al. Ovarian endometrioma - a possible finding in adolescent girls and young women: a mini-review. Journal of Ovarian Research 12 (2019): 104.

- Lee, H. J., Park, Y. M., Jee, B. C., et al. Various anatomic locations of surgically proven endometriosis: A single-center experience. Obstet Gynecol Sci 58 (2011), 53-58.

- Sznurkowski, J. J. C Emerich, J. Endometriomas are more frequent on the left side. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 87 (2008): 104-106.

- Matalliotakis, I. M. et al. Arguments for a left lateral predisposition of endometrioma. Fertil Steril G1 (2009): 975-978.

- Eshkoli, T., Weintraub, A. Y., Erenberg, M., et al. The laterality of endometriosis. Journal of Endometriosis and Uterine Disorders 3 (2023): 100039.

- Vercellini, P. et al. Is cystic ovarian endometriosis an asymmetric disease? Br J Obstet Gynaecol 105 (1998): 1018-1021.

- Sznurkowski, J. J. C Emerich, J. Endometriomas are more frequent on the left side. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica 87 (2008): 104-106.

- Chapron, C. et al. Does deep endometriosis infiltrating the uterosacral ligaments present an asymmetric lateral distribution? BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 108 (2001), 1021-1024.

- Matalliotakis, I. M. et al. Arguments for a left lateral predisposition of endometrioma. Fertil Steril G1 (2009): 975-978.

- Guerriero, S. et al. Addendum to consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group: sonographic evaluation of superficial endometriosis. Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology 66 (2025): 541-547.

- Guerriero, S. et al. Systematic approach to sonographic evaluation of the pelvis in women with suspected endometriosis, including terms, definitions and measurements: a consensus opinion from the International Deep Endometriosis Analysis (IDEA) group. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 48 (2016): 318-332.

- Exacoustos, C., Manganaro, L. C Zupi, E. Imaging for the evaluation of endometriosis and adenomyosis. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology 28 (2014): 655-681.

- Petraglia, F., Vannuccini, S., Santulli, P., et al. An update for endometriosis management: a position statement. Journal of Endometriosis and Uterine Disorders 6 (2024): 100062.

- Angioni, S. et al. Is dienogest the best medical treatment for ovarian endometriomas? Results of a multicentric case control study. Gynecological Endocrinology 36 (2020): 84-86.

- Treatment of endometriosis: a review with comparison of 8 guidelines | BMC Women’s Health | Full Text. https://bmcwomenshealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12905- 021-01545-5.

- Vignali, M. et al. Effect of Dienogest therapy on the size of the endometrioma. https://air.unimi.it/handle/2434/726511 (2020).

- Huang, Y., Zhang, D., Zhang, L., et al. Clinical efficacy of dienogest against endometriomas with a maximum diameter of ≥4 cm. Ann Med 56 (2024): 2402942.

- Aizzi, F. J. Recurrent Endometrioma; Outcome of Medical Management with Dienogest. European Journal of Experimental Biology 7, 0-0.

- Momoeda, M. et al. Long-term use of dienogest for the treatment of endometriosis. J of Obstet and Gynaecol 35 (2009), 1069-1076.

- Carrillo Torres, P. et al. Clinical and sonographic impact of oral contraception in patients with deep endometriosis and adenomyosis at 2 years of follow-up. Sci Rep 13 (2023): 2066.

- Petri, H. C Urquhart, J. Channeling bias in the interpretation of drug effects. Stat Med 10 (1991): 577-581.

Impact Factor: * 3.2

Impact Factor: * 3.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.63%

Acceptance Rate: 76.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks