Patterns of Primary Surgical Indications in Laparotomy Cases Following LUCS and TAH

Dr.nur -un-naher nazme1, Dr. Mst. Shorifa Rani2, Dr. Tasnim Mahmud3*

1junior consultant (0bs&gynae), 250bed general hospital. Joypurhat.

2Junior consultant (Obs and Gynae), Upazilla health complex Charghat, Rajshahi.

3Department of Public Health, North South University Dhaka, Bangladesh

*Corresponding authors: Dr. Tasnim Mahmud, Department of Public Health, North South University Dhaka, Bangladesh

Received: 01 December 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Published: 17 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Dr.nur -un-naher nazme, Dr. Mst. Shorifa Rani, Dr. Tasnim Mahmud. Patterns of Primary Surgical Indications in Laparotomy Cases Following LUCS and TAH. Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 8 (2025): 197-202.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background:

Emergency laparotomy is a major surgical procedure performed to address life-threatening intra-abdominal complications such as haemorrhage, sepsis, or organ injury. When required as a re-exploration following obstetric or gynaecological surgery, it represents a serious event associated with increased morbidity and mortality. The growing frequency of caesarean sections and hysterectomies worldwide has contributed to a corresponding rise in postoperative complications that may necessitate relaparotomy.

Objective:

To determine the distribution of indications for primary Lower Uterine Segment Caesarean Section (LUCS) and Total Abdominal Hysterectomy (TAH) among patients who subsequently underwent laparotomy.

Methods:

This retrospective cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2011 to April 2012 in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Rajshahi Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh. Hospital records of 41 patients who underwent laparotomy following primary obstetric or gynaecological surgery were reviewed. Data regarding surgical indication, timing of relaparotomy, hospital stay, and patient outcomes were analyzed using descriptive statistics, and results were expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Results:

Among the 41 relaparotomy cases, 34 (82.93%) followed LUCS and 7 (17.07%) followed TAH. The most common indications for primary LUCS were term pregnancy with previous caesarean section (17.07%) and oligohydramnios (14.64%), while fibroid uterus (42.85%) and bulky uterus (42.85%) were the predominant indications among TAH cases. Most relaparotomies (39.02%) occurred within 15–42 days of the initial surgery. The survival rate was 82.93%, and mortality was recorded in 17.07% of cases.

Conclusion:

Previous caesarean delivery and benign uterine disorders were the leading indications for primary surgeries among patients requiring relaparotomy. Early identification of high-risk patients, meticulous intraoperative technique, and vigilant postoperative monitoring are essential to prevent avoidable re-explorations and improve patient outcomes.

Keywords

<p>Laparotomy; LUCS; surgery; TAH</p>

Article Details

Introduction:

Emergency laparotomy is a major surgical intervention performed to manage life-threatening intra-abdominal conditions such as haemorrhage, sepsis, or organ perforation. It is associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality, especially when carried out as a re-exploration following obstetric or gynaecological procedures [1,2]. Despite improvements in surgical techniques, anaesthesia, and perioperative care, postoperative complications after abdominal operations remain a significant global challenge [3].

In obstetric practice, caesarean section (CS) is one of the most commonly performed major surgeries worldwide. The rising global trend of CS, often exceeding the World Health Organization’s recommended limit of 10–15 %, has been linked to an increased risk of postoperative complications and the need for subsequent surgical interventions such as relaparotomy [4,5]. Factors including uterine rupture, postpartum haemorrhage, wound infection, and bladder or bowel injury contributes to the need for emergency re-exploration following CS [6,7].

Similarly, in gynaecological surgery, total abdominal hysterectomy (TAH) remains a standard operation for benign uterine disorders such as fibroids, dysfunctional uterine bleeding, and bulky uterus [8,9]. Although generally safe, hysterectomy can occasionally lead to postoperative complications such as haemorrhage, pelvic abscess, intestinal obstruction, or urinary tract injury, sometimes necessitating further laparotomy [10,11].

The burden of relaparotomy following obstetric and gynaecological surgeries is particularly concerning in low- and middle-income countries, where limited resources, delayed presentation, and restricted access to advanced perioperative support can worsen patient outcomes [12,13]. Understanding the initial indications that led to these primary surgeries is therefore essential in identifying high-risk cases, improving intraoperative decision-making, and reducing the frequency of re-explorations [14].

This retrospective cross-sectional study aimed to determine the distribution of indications for primary Lower Uterine Caesarean Section (LUCS) and Total Abdominal Hysterectomy (TAH) among patients who subsequently underwent laparotomy.

Study Design:

This study was a retrospective cross-sectional observational study conducted from November 2011 to April 2012, in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology at Rajshahi Medical College Hospital (RMCH), Bangladesh. The study period covered all cases managed during a defined timeframe in which patients underwent laparotomy following a primary obstetric or gynaecological surgery. Hospital records, operative notes, and discharge summaries were reviewed to extract relevant data.

The study population comprised all female patients who underwent relaparotomy (re-exploration of the abdomen) after an initial obstetric or gynaecological operation within the study period. A total of 41 patients were included in the final analysis. Among them, 34 cases had previously undergone a Lower Uterine Segment Caesarean Section (LUCS), and 7 cases had undergone a Total Abdominal Hysterectomy (TAH) as their primary surgery.

Inclusion Criteria

- • Patients who underwent laparotomy following LUCS or TAH.

- • Cases with complete hospital records containing operative and postoperative details.

- • Patients admitted to or referred to RMCH during the study period.

Exclusion Criteria

- • Patients who underwent laparotomy for reasons unrelated to obstetric or gynaecological surgery.

- • Incomplete medical records or missing operative documentation.

- • Patients referred after undergoing laparotomy elsewhere.

Data Collection Procedure

Data were collected retrospectively from hospital case sheets, operative registers, and patient discharge summaries. The following variables were recorded: age, indication of primary surgery, time interval between primary surgery and laparotomy, duration of hospital stay, surgical findings, and patient outcome. Each variable was carefully cross-checked to ensure accuracy and completeness of the data.

Statistical Analysis

All data were entered and analyzed using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 25.0. Descriptive statistics were applied to summarize the data. Frequencies and percentages were calculated for categorical variables such as surgical indication, time interval between surgeries, and outcomes. Results were presented in tabular form for clarity. Quantitative data such as hospital stay were expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) where appropriate.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). Ethical clearance was obtained from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Rajshahi Medical College Hospital prior to data collection. As this was a retrospective study, patient confidentiality was strictly maintained, and no personal identifiers were used in the analysis or reporting.

Result:

This present study resembles that, a total of 13688 patients were admitted in Obs and Gynae Department of Rajshahi Medical College hospital out of which 41 (0.299%) patients underwent relaparotomy.

Table 1 (A): Distribution by Indication of primary surgery (LUCS) who under-went laparotomy (n=41)

Table 1 (A) resembles distribution by Indication of primary surgery (LUCS) who under-went laparotomy. Among the 34 patients who underwent laparotomy following LUCS, the most frequent indication for the primary surgery was term pregnancy with a previous cesarean section (17.07%), followed by term pregnancy with oligohydramnios (14.64%). Other relatively frequent causes included breech presentation, postdated pregnancy with prolonged labour, and labour pain at term (each around 7%). These findings suggest that a history of cesarean section and complications related to amniotic fluid or labour were major contributors to subsequent laparotomy in obstetric patients.

|

Indication |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Term pregnancy with previoas c/s |

7 |

17.07% |

|

Term with obstructed labour 1 |

3 |

70.30% |

|

36 weeks twin with prolong labour |

1 |

2.44% |

|

Term pregnancy with labour pain |

3 |

7032% |

|

38 weeks pregnancy with control placenta previa |

2 |

4.88 |

|

Term pregnancy breech presentation |

3 |

7.32% |

|

Postdated pregnancy with prolong labour |

3 |

7.32% |

|

Term pregnancy with malpresentation |

2 |

4.88% |

|

Term pregnancy with oligohydramnios |

6 |

14.64% |

|

Postdated pregnancy |

3 |

7.32% |

|

36 weeks pregnancy with severe PET |

1 |

2.44% |

Table: 1(B) Distribution by indication of primary surgery (TAH) who under-went laparotomy following gynaecological surgery (n=41)

Table 1 (B) illustrates distribution by indication of primary surgery (TAH) who under-went laparotomy following gynaecological surgery. It is evident that, among the seven patients who underwent laparotomy following TAH, the majority had surgery for fibroid uterus (42.85%) and bulky uterus (42.85%), with a smaller proportion for dysfunctional uterine bleeding (14.30%). These findings indicate that benign uterine pathologies were the leading causes of laparotomy following gynecological surgery.

|

Indication |

Frequency (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

Fibroid uterus |

3 |

42.85% |

|

Bulky uterus |

3 |

42.85% |

|

Dysfunctional uterine bleeding |

1 |

14.18 |

|

Total |

7 |

100% |

Table:2 Distribution of time interval form primary surgery to laparotomy (n=41)

Table 2 shows distribution of time between primary surgery & relaparotomy. Total 16 cases had relaparotomy within 15-42 days. 14 cases had relaparotomy within 24 hours, 3 cases within 24-72 hours, 8 cases within 8 -14 days.

|

Time interval |

Number of cases |

Percentage |

|

0-24 hours |

14 |

34.15 |

|

24-72 hours |

3 |

7.32 |

|

8-14 days |

8 |

19.51 |

|

15-42 days |

16 |

39.02 |

Table:3 Distribution by showing Duration of hospital stay (n=41)

Table: 3 Shows duration of hospital stay. More than 20 days hospital stay needed in case of 11 cases. 10 cases needed 6-10 days hospital stay. 6 cases needed 11-15 days & 6 cases needed 1-5 days.

|

Period (days) |

Number of cases (n) |

Percentage (%) |

|

01-May |

6 |

14.63 |

|

06-Oct |

10 |

24.39 |

|

Nov-15 |

6 |

14.63 |

|

16-20 |

8 |

19.51 |

|

>20 |

11 |

26.83 |

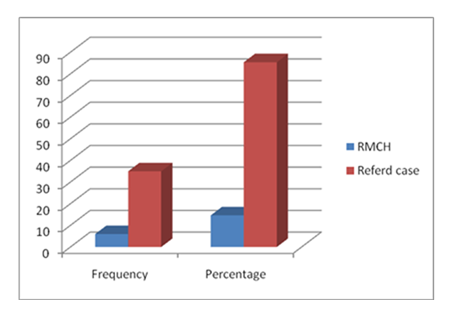

Figure: 1 illustrates distribution by place of operation. It is found that, number of cases done in RMCH is 6 & Referred cases were 35 (85.37%) in number.

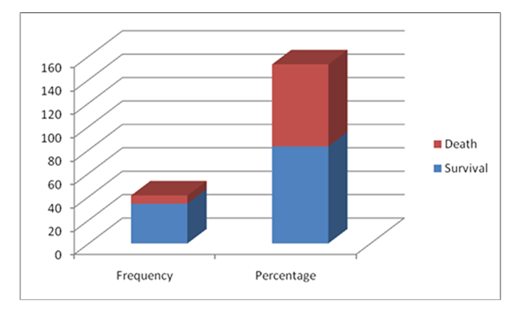

Figure:2, shows distribution by outcome of critically ill patients following relaparotomy. Survival rate 82.93% (34 cases) & death 17.07% (7cases).

Discussion:

In this study, a total of 41 patients underwent laparotomy following obstetric and gynaecological surgeries, accounting for 0.299% of all surgical admissions during the study period. Among these, 34 cases followed Lower Uterine Segment Caesarean Section (LUCS), and 7 followed Total Abdominal Hysterectomy (TAH). This finding indicates that laparotomy as a re-exploration procedure is relatively uncommon but represents a serious complication when it occurs, echoing observations from earlier studies that reported rates ranging between 0.2% and 0.7% after major abdominal operations [15,16].

The most frequent indication for the primary obstetric surgery in this study was term pregnancy with a previous caesarean section (17.07%), followed by oligohydramnios (14.64%). This pattern is consistent with findings by Shan et al. (2023), who identified previous caesarean section and labour complications as major risk factors for subsequent relaparotomy after LUCS [17]. Similarly, Unalp et al. (2006) reported that postoperative haemorrhage and uterine rupture were among the common causes of re-exploration after obstetric surgeries [18]. The predominance of previous scar pregnancies in our series suggests that surgical adhesions and scar dehiscence remain significant contributors to postoperative morbidity in repeat caesarean deliveries, as also noted in studies from India and Ethiopia [19,20].

Among the gynaecological cases, fibroid uterus (42.85%) and bulky uterus (42.85%) were the most common primary indications for TAH in patients who later required laparotomy. This aligns with reports by Kaur et al. (2018) and Uzelac (2021), who found benign uterine pathologies—particularly leiomyomas and dysfunctional uterine bleeding—as the leading causes of hysterectomy and subsequent postoperative complications [21,22]. The recurrence of postoperative haemorrhage, pelvic abscess, and bowel injury has been documented as the main reasons for re-exploration in similar series [23,24].

In our study, the majority of relaparotomies occurred within the first 15–42 days following the initial operation, with 34.15% taking place within 24 hours. These findings are comparable to those of Sahu et al. (2020), who reported that early postoperative haemorrhage and peritonitis were the most frequent reasons for relaparotomy within the first week [25]. Delayed re-explorations, as observed in our cohort, may reflect postoperative infection, adhesion formation, or wound dehiscence developing over time [26].

The overall survival rate of 82.93% in this series indicates a favourable outcome compared with older data from resource-limited settings, where mortality following relaparotomy ranged from 20–40% [27]. The improvement in survival may be attributed to advances in anaesthetic care, better surgical techniques, and earlier recognition of postoperative complications. Nevertheless, the mortality rate of 17.07% remains clinically significant and emphasizes the need for prompt diagnosis, adequate resuscitation, and timely surgical intervention to reduce preventable deaths [28].

Our results reinforce that previous caesarean delivery and benign uterine pathologies are the most frequent underlying causes for laparotomy after primary obstetric and gynaecological surgeries. This observation aligns with global trends indicating an increasing burden of postoperative morbidity due to rising caesarean section rates and a high prevalence of uterine fibroids in women of reproductive age [29,30]. Early identification of at-risk patients, meticulous surgical technique, and strict postoperative monitoring are crucial in reducing the incidence of such complications.

Limitations

The main limitation of this study is its retrospective design and single-centre nature, which may limit generalizability. In addition, detailed intraoperative findings and long-term follow-up data were not available for all cases. Despite these limitations, the study provides valuable insight into the local pattern of surgical indications leading to laparotomy and highlights areas for quality improvement in obstetric and gynaecological surgical practice.

Conclusion

The present study demonstrates that term pregnancy with previous caesarean section and fibroid uterus are the most common primary indications leading to laparotomy following obstetric and gynaecological surgeries. Most relaparotomies occurred within the first few weeks of the initial procedure, with haemorrhage and infection being the predominant causes. Strengthening intraoperative vigilance, early complication detection, and postoperative care can significantly improve outcomes and reduce the need for re-exploration.

References

- Unalp HR, Kamer E, Kar H, et al. Urgent abdominal re-explorations. World J Emerg Surg 1 (2006): 10.

- Abebe K, Geremew B, Lemmu B, Abebe E. Indications and outcome of patients who had re-laparotomy: two years’ experience from a teaching hospital in a developing nation. Ethiopian journal of health sciences 30 (2020).

- Sak ME, Turgut A, Evsen MS, et al. Relaparotomy after initial surgery in obstetric and gynecologic operations: analysis of 113 cases. Ginekologia polska 83 (2012).

- WHO H. WHO statement on caesarean section rates. Geneva, Switzerland. 2015 Apr.

- Shan D, Han J, Tan X, et al. Mortality rate and risk factors for relaparotomy after caesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC pregnancy and childbirth 25 (2025): 269.

- Rouf S, Sharmin S, Dewan F, Akhter S. Relaparotomy after Cesarean section: experience from a tertiary referral and teaching hospital of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 24 (2009): 3-9.

- Chan GJ, Daniel J, Getnet M, et al. Gaps in maternal, newborn, and child health research: a scoping review of 72 years in Ethiopia. medRxiv. 2021 Jan 20: 2021-01.

- Chan YG, Ho HK, Chen CY. Abdominal hysterectomy: indications and complications. Singapore medical journal 34 (1993): 337

- Dorsey JH, Steinberg EP, Holtz PM. Clinical indications for hysterectomy route: patient characteristics or physician preference?. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 173 (1995): 1452-1460.

- Whynott RM, Vaught KC, Segars JH. The effect of uterine fibroids on infertility: a systematic review. InSeminars in reproductive medicine 2017 Nov (Vol. 35, No. 06, pp. 523-532). Thieme Medical Publishers.

- Meltomaa SS, Mäkinen JI, Taalikka MO, Helenius HY. One-year cohort of abdominal, vaginal, and laparoscopic hysterectomies: complications and subjective outcomes. Journal of the American College of Surgeons 189 (1999): 389-396.

- Sharma A, Sahu SK, Nautiyal M, Jain N. To study the aetiological factors and outcomes of urgent re-laparotomy in Himalayan Hospital. Chirurgia (Bucur) 111 (2016): 58-63.

- Sak ME, Turgut A, Evsen MS, et al. Relaparotomy after initial surgery in obstetric and gynecologic operations: analysis of 113 cases. Ginekologia polska 83 (2012).

- Lewi L, Gutvirtz G, Wainstock T, et al. Exploring the risk factors for relaparotomy following cesarean delivery. Archives of Gynecology and Obstetrics 3 (2025): 1-6.

- Unalp HR, Kamer E, Kar H, Bal A, Peskersoy M, Onal MA. Urgent abdominal re-explorations. World J Emerg Surg 1 (2006): 10.

- Ching SS, Muralikrishnan VP, Whiteley GS. Relaparotomy: a five-year review of indications and outcome. International journal of clinical practice 57 (2003): 333-337.

- Shan D, Han J, Tan X, et al. Mortality rate and risk factors for relaparotomy after cesarean section: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 23 (2023): 269.

- Rouf S, Sharmin S, Dewan F, Akhter S. Relaparotomy after Cesarean section: experience from a tertiary referral and teaching hospital of Bangladesh. Bangladesh Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology 24 (2009): 3-9.

- Netsere HB, Miskir Y, Berhie AY, et al. Prevalence and determinants of relaparotomy in East African healthcare institutions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC surgery 25 (2025): 362.

- Srivastava P, Qureshi S, Singh U. Relaparotomy: review of indications and outcome in tertiary care hospital. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 5 (2016): 520-524.

- Sharma S, Kaur K, Sood R, et al. Emerging Trends in Peripartum Hysterectomy: A Retrospective Study in a Tertiary Care Center over 2 Years. AMEI's Current Trends in Diagnosis & Treatment 3 (2019): 8-12.

- Carlson KJ, Nichols DH, Schiff I. Indications for hysterectomy. New England Journal of Medicine 328 (1993): 856-860.

- Litta P, Saccardi C, Conte L, et al. Reverse hysterectomy: another technique for performing a laparoscopic hysterectomy. Journal of Minimally Invasive Gynecology 20 (2013): 631-636.

- Varlas VN, Bălescu I, Varlas RG, et al. Complete Abdominal Evisceration After Open Hysterectomy: A Case Report and Evidence-Based Review. Journal of Clinical Medicine 14 (2025): 262.

- Martínez-Casas I, Sancho JJ, Nve E, et al. Preoperative risk factors for mortality after relaparotomy: analysis of 254 patients. Langenbeck's archives of surgery 395 (2010): 527-34.

- Sharma A, Sahu SK, Nautiyal M, Jain N. To study the aetiological factors and outcomes of urgent re-laparotomy in Himalayan Hospital. Chirurgia (Bucur) 111 (2016): 58-63.

- Devi S, Ratna G. Relaparotomy After Caesarean Section-A Study in Tertiary Care Hospital. IOSR Jou Den Med Sci (IOSR-JDMS) 1 (2019): 5-8.

- Srivastava P, Qureshi S, Singh U. Relaparotomy: review of indications and outcome in tertiary care hospital. Int J Reprod Contracept Obstet Gynecol 5 (2016): 520-524.

- Betran AP, Ye J, Moller AB, et al. Trends and projections of caesarean section rates: global and regional estimates. BMJ global health 6 (2021): e005671.

- Stewart EA, Cookson CL, Gandolfo RA, Schulze-Rath R. Epidemiology of uterine fibroids: a systematic review. BJOG 124 (2017): 1501-1512.

Impact Factor: * 3.2

Impact Factor: * 3.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.63%

Acceptance Rate: 76.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks