Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Versus Systematic Lymphadenectomy in Endometrial Cancer: Real-World Evidence from a Propensity Score- Matched European Cohort

Mikel Gorostidi, MD, MSc, PhD1,2,3, Marta Heras*, MD, PhD4, Mª Teresa Iglesias, PhD5,6, Mar Rubio, MD1, Nabil Manzour, MD1, Rubén Ruiz Sautua, MD1, Ibon Jaunarena, MD1,2, Juan Céspedes, MD1, Paloma Cobas, MD1, Arantxa Lekuona, MD (Chief of Department)1,2,3

1Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hospital Universitario Donostia, Osakidetza, 20014 San Sebastián, Spain

2BIOGIPUZKOA Health Research Institute, 20014 San Sebastián, Spain

3Basque Country University (UPV/EHU), 48940 Leioa, Spain

4Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hospital Universitario Santa Cristina, 28009 Madrid, Spain

5Unidad de Epidemiología Clínica e Investigación, Hospital Universitario Donostia, Osakidetza, 20014 San Sebastián, Spain

6Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Deusto, San Sebastián, Spain

* Corresponding authors: Marta Heras, MD, PhD. Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Hospital Universitario Santa Cristina, 28009 Madrid, Spain.

Received: 18 December 2025; Accepted: 24 December 2025; Published: 31 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Mikel Gorostidi, MD, MSc, PhD, Marta Heras, MD, PhD, Mª Teresa Iglesias, PhD, Mar Rubio, MD, Nabil Manzour, MD, Rubén Ruiz Sautua, MD, Ibon Jaunarena, MD, Juan Céspedes, MD, Paloma Cobas, MD, Arantxa Lekuona, MD. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy Versus Systematic Lymphadenectomy in Endometrial Cancer: Real- World Evidence from a Propensity Score-Matched European Cohort. Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 8 (2025): 208-216.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background:

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy has been proposed as a less invasive alternative to systematic lymphadenectomy (LND) in endometrial cancer staging. Robust real-world evidence comparing both approaches with adequate statistical adjustment remains limited.

Methods:

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of patients with histologically confirmed endometrial carcinoma who underwent primary surgical staging at Donostia University Hospital (2014–2023). Patients were classified according to nodal assessment strategy: SLN biopsy alone or SLN biopsy plus LND. Mapping was performed using dual indocyanine green injection and laparoscopic near-infrared detection. Propensity score matching (3:1 nearest neighbor) was applied using demographic, clinicopathological, and FIGO 2009 stage variables. Surgical, pathological, and oncologic outcomes were compared.

Results:

A total of 448 patients were included (116 SLN-alone, 332 SLN+LND). After Propensity Score- Matched (PSM), 439 patients were analyzed (112 vs 327). SLN biopsy alone was associated with shorter hospital stay (–1.05 days; p<0.001) and reduced lymphadenectomy rates (p<0.001), without differences in hemoglobin drop. Detection rates were comparable, with significantly higher three-zone detection in the SLN group (p=0.003). No significant differences were observed in progressionfree survival (HR 1.90, 95% CI 0.89–4.04) or overall survival (HR 1.50, 95% CI 0.57–4.11), including patients classified as preoperative high-risk.

Conclusion:

SLN biopsy provides comparable oncologic outcomes to systematic lymphadenectomy while significantly reducing surgical morbidity. These findings add large-scale European real-world evidence supporting SLN biopsy as a safe staging strategy in appropriately selected patients and may support future European guideline recommendations.

Keywords

<p>Endometrial cancer; Sentinel lymph node; Lymphadenectomy; Ultrastaging; indocyanine green; Near-infrared fluorescence; Propensity score; Survival</p>

Article Details

Introduction:

Endometrial cancer is the most frequent gynecologic malignancy in developed countries. Accurate surgical staging remains pivotal for prognostication and for tailoring adjuvant therapy, so it must include lymph node assessment [1]. Historically, pelvic and para aortic lymphadenectomy (LND) has been incorporated into staging algorithms; however, this approach increases operative time and is associated with clinically relevant morbidity, including lymphocele formation and lower limb lymphedema [2–5]. The completion of lymphadenectomy enables histological analysis of lymph node status, in order to establish a proper tumor staging and the removal of lymphatic tumoral burden in some cases. Nonetheless, a systematic lymphadenectomy has not demonstrated survival benefit in most early-stage settings, since those tumors do not have lymph node involvement [6,7].

Sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping has emerged as a less invasive alternative that preserves staging information while potentially reducing surgical harm [8]. Since the introduction of SLN technique for oncological surgery, effort has been made to extend its applicability to a greater number of tumors [9]. In endometrial cancer, many studies have been developed to prove feasibility of SLN and avoid systematic lymphadenectomy in the absence of lymph node involvement. Initially, evidence was retrospective, mostly in low- risk tumors and using different tracers [10,11]. The SENTI-ENDO trial was the first prospective study to evaluate SLN in endometrial cancer, although it used Tc-99 combined with blue- dye as tracers [12]. The reported detection rate was less than 90%, which led to the use of ICG as the standard tracer for endometrial cancer [13].

Many studies have been made to evaluate the role of systematic lymphadenectomy versus SLN assessment for endometrial cancer, with uneven results [14]. Most of the studies have proven increased detection rate of metastasis when systematic lymphadenectomy was performed, with no increase in survival, as proven in the ASTEC trial [15]. The diagnostic accuracy of SLN—especially when combined with standardized ultrastaging—has been validated in multi institutional studies, demonstrating high sensitivity and negative predictive value for nodal metastases [6,7]. Nevertheless, important questions persist regarding the ability of SLN algorithms to capture extra pelvic (para aortic) disease, the performance in non endometrioid/high grade histologies, and the real world oncologic equivalence of SLN versus systematic LND beyond controlled trial environments [16].

In parallel, technical refinements such as dual site indocyanine green (ICG) injection and near infrared laparoscopy have expanded mapping success and may improve detection in upper pelvic and para aortic basins [17,18]. Yet, comparative effectiveness data from European practice, with adequate control for baseline imbalances between patients selected for SLN alone versus SLN plus LND, remain limited.

Therefore, the present study compares surgical, pathological, and oncologic outcomes of SLN biopsy alone versus SLN plus systematic lymphadenectomy in a large, single center European cohort. To emulate trial conditions and mitigate treatment selection bias, we applied propensity score matching and prespecified subgroup analyses, including patients with preoperative high risk features.

Methods

Study Design and Setting

We performed a retrospective cohort study at Donostia University Hospital (San Sebastián, Spain). Consecutive patients with histologically confirmed endometrial carcinoma who underwent primary surgical staging between January 2014, and December 2023 were included. The study was approved by the institutional ethics committee, and all patients provided written informed consent for data use.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria were: (i) epithelial endometrial carcinoma confirmed preoperatively, (ii) primary surgical staging by a minimally invasive approach, and (iii) at least 12 months of follow-up. Exclusion criteria were non-epithelial histologies (e.g., uterine sarcomas), incomplete surgical staging, or missing essential clinicopathological data.

Risk Stratification and Staging

Preoperative high-risk status was defined according to ESGO–ESMO–ESTRO consensus criteria, including unfavorable histology (serous, clear cell, undifferentiated, carcinosarcoma), grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma, deep myometrial invasion (>50%), cervical stromal involvement, or radiologic/intraoperative suspicion of nodal or extrauterine disease. Patients were staged according to the FIGO 2009 [19] classification system, with stage I to stage III subcategories regrouped as single categories.

Surgical Procedures

In the SLN group, mapping was performed with a dual indocyanine green (ICG) injection prepared at 2.5 mg/mL, administered at the cervix at 3 and 9 o’clock, both superficial and deep (1 mL at each site), plus a transcervical fundal injection of 2 mL, followed by laparoscopic detection using near-infrared fluorescence ) [17], Sentinel nodes were submitted for ultrastaging. SLN detection was assessed in three anatomical regions—right pelvis, left pelvis, and paraaortic (aortocaval)—and categorized as no detection, unilateral pelvic, bilateral pelvic, or three-zone detection (bilateral pelvic plus paraaortic). In the SLN+LND group, the same SLN technique was performed and then followed by systematic bilateral pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy up to the renal vessels according to institutional protocols. In patients classified as low-risk by preoperative stratification, systematic lymphadenectomy was not indicated irrespective of SLN detection, whereas it was performed in all other cases.

Outcomes

- • Surgical: estimated blood loss, length of stay, lymphadenectomy performed

- • Pathological: SLN detection rates.

- • Oncologic: disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS), measured from surgery to recurrence, death, or last follow-up.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were reported as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or median (interquartile range, IQR) and compared using t-test or Mann–Whitney U test, as appropriate. Categorical variables were analyzed using χ² or Fisher’s exact test. Survival outcomes were assessed with Kaplan–Meier curves and compared using the log-rank test. Median follow-up was estimated by the reverse Kaplan–Meier method, both overall and stratified by treatment group, using OS and PFS times to provide unbiased measures of observation time. Multivariable Cox regression was used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

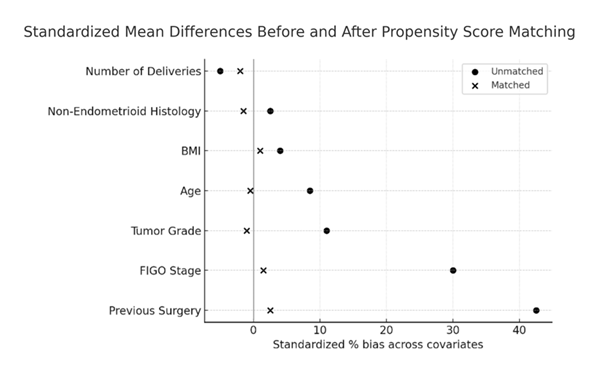

To reduce selection bias, propensity scores for each patient were generated using a multivariate logistic regression model using patient characteristics: age, body mass index (BMI), parity, prior surgery, ASA score, histology, tumor grade, depth of myometrial invasion, and FIGO 2009 stage. These variables were selected based on established prognostic relevance in endometrial carcinoma and on expert consensus. Because the original FIGO 2009 staging subcategories did not allow adequate covariate balance, stage was recoded into broader categories prior to matching. Three matching strategies were tested (nearest neighbor 1:1, caliper 0.2, and nearest neighbor 3:1), as detailed in the Supplementary Material [20]. All three approaches yielded consistent results in terms of reduction of bias, as detailed in the Supplementary Tables, which reinforces the robustness of our findings. The neighbor (3:1) algorithm provided the best covariate balance and so this method was used for the final analysis. The patients were matched using the nearest neighbor (3:1) method without replacement and without caliper for the final analysis. Balance was evaluated using standardized differences to quantify differences in means between the two groups and illustrated with love plots (Figure 1).

Two-sided p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed with Stata/SE v18.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, USA).

Results

A total of 448 patients were included: 332 in the SLN+LND group and 116 in the SLN-alone group. Baseline demographic and clinicopathological characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Prior surgery and final FIGO stage distribution differed significantly between groups (p<0.001), while age, BMI, parity, ASA score, histology, and tumor grade were comparable.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of the control group (SLN+LND) and the experimental group (SLN alone). Continuous variables are presented as mean and standard deviation (SD), while categorical variables are expressed as absolute number (n) and percentage (%).

|

Variable |

SLN + LND (n 332) |

SLN alone (n 116) |

p-value |

||

|

Age (years, mean ± SD) |

62.9 ± 10.3 |

63.8 ± 10.4 |

0.3883 |

||

|

BMI (kg/m², mean ± SD) |

28.7 ± 5.6 |

28.7 ± 6.3 |

0.9529 |

||

|

Number of deliveries |

1.7 ± 1.2 |

1.5 ± 1.2 |

0.3043 |

||

|

Prior surgery, n (%) |

140 (42.3%) |

72 (62.6%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

ASA Score, n (%) |

0.068 |

||||

|

· 1 |

27 (8.2%) |

10 (8.6%) |

|||

|

· 2 |

227 (68.6%) |

64 (55.2%) |

|||

|

· 3 |

72 (21.8%) |

37 (31.9%) |

|||

|

· 4 |

5 (1.5%) |

3 (2.6%) |

|||

|

· missing |

2 (1.7%) |

||||

|

Histology, n (%) |

0.758 |

||||

|

· Endometrioid |

284 (85.5%) |

100 (86.2%) |

|||

|

· Non-endometrioid |

48 (14.5%) |

15 (12.9%) |

|||

|

· missing |

1 (0.9%) |

||||

|

Tumor grade (High), n (%) |

26 (22.9%) |

32 (27.6%) |

0.315 |

||

|

Final FIGO Stage, n (%) |

<0.001 |

||||

|

· I |

301 (90.7%) |

100 (86.2%) |

|||

|

· II |

28 (8.4%) |

8 (6.9%) |

|||

|

· III |

3 (0.9%) |

7 (6.1%) |

|||

|

· IV |

0 |

1 (0.9%) |

Propensity Score Matching (PSM)

After applying nearest-neighbor propensity score matching at a 3:1 ratio, 439 patients were analyzed (327 SLN+LND vs. 112 SLN-alone). Propensity score matching relies on two key assumptions: conditional independence (ignorability) and common support [21]; the latter was verified by confirming overlap of the propensity score distributions between groups (Supplementary Material).

As shown in Table 2, the 3:1 nearest-neighbor approach substantially improved covariate balance, eliminating the pre-matching differences observed in previous surgery and final FIGO stage.

Table 2: Balance of covariates between SLN+LND and SLN alone groups before (unmatched) and after (matched) propensity score matching (neighbor 3:1). Mean values, percentage bias, bias reduction, and corresponding *p*-values from t-tests are shown. Abbreviations: SLN = sentinel lymph node; LND = lymphadenectomy.

|

Variables |

SLN+LND (mean) |

SLN alone (mean) |

% Bias |

% Reduct (Bias) |

p |

|||

|

Age |

Unmatched |

63.76 |

62.87 |

8.4 |

18.5 |

0.438 |

||

|

Matched |

63.76 |

64.48 |

-6.8 |

0.623 |

||||

|

BMI |

Unmatched |

28.49 |

28.63 |

-2.3 |

-58 |

0.828 |

||

|

Matched |

28.49 |

28.27 |

3.7 |

0.776 |

||||

|

Deliveries |

Unmatched |

15.18 |

16.64 |

-11.9 |

51 |

0.28 |

||

|

Matched |

15.18 |

15.89 |

-5.8 |

0.669 |

||||

|

Previous |

Unmatched |

0.634 |

0.422 |

43.3 |

100 |

<0.001 |

||

|

surgeries |

Matched |

0.634 |

0.634 |

0 |

1 |

|||

|

Unfavorable histologies |

Unmatched |

0.134 |

0.147 |

-3.7 |

-62 |

0.738 |

||

|

Matched |

0.134 |

0.155 |

-6 |

0.659 |

||||

|

High tumoral |

Unmatched |

0.268 |

0.226 |

9.6 |

85.7 |

0.373 |

||

|

grade |

Matched |

0.268 |

0.278 |

-1.4 |

0.921 |

|||

|

Final FIGO stage |

Unmatched |

12.05 |

1.104 |

22.1 |

94.1 |

0.022 |

||

|

Matched |

12.05 |

11.99 |

1.3 |

0.931 |

||||

Covariate balance was achieved across all baseline variables, with standardized mean differences <10% (Figure 1).

Table 3 summarizes the sample sizes for each outcome before and after propensity score matching. The loss of cases due to matching was minimal, and only a few missing values were observed. Overall, distributions between SLN+LND and SLN Alone groups remained well balanced, and the small discrepancies in sample size did not materially impact the analyses.

Table 3: Sample sizes for each outcome in both study groups, before and after nearest-neighbor propensity score matching (3:1).

|

OUTCOME |

WITHOUT PROPENSITY |

WITH PROPENSITY |

Missing |

||

|

SLN+LND |

SLN Alone |

SLN+LND |

SLN Alone |

value |

|

|

Continuous Outcome: |

|||||

|

Hospitalization days |

332 |

115 |

327 |

112 |

8 |

|

Hemoglobin drop (Hb) |

323 |

109 |

319 |

106 |

7 |

|

Binary Outcome: |

|||||

|

Lymphadenectomy |

|||||

|

· Yes |

151 |

113 |

148 |

110 |

5 |

|

· No |

181 |

1 |

179 |

1 |

3 |

|

Aortic detection |

|||||

|

· Yes |

226 |

92 |

222 |

89 |

7 |

|

· No |

106 |

21 |

105 |

21 |

1 |

|

Bilateral pelvic detection |

|||||

|

· Yes |

234 |

94 |

229 |

93 |

6 |

|

· No |

19 |

98 |

19 |

17 |

2 |

|

Three-zone detection |

|||||

|

· Yes |

178 |

76 |

174 |

75 |

5 |

|

· No |

154 |

38 |

153 |

36 |

3 |

Surgical, Pathological and Oncologic Outcomes

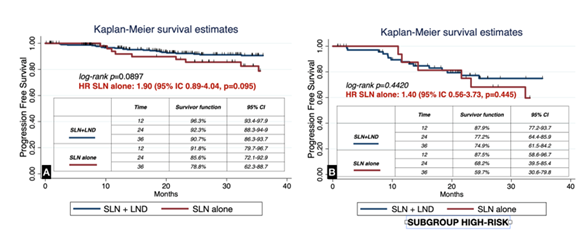

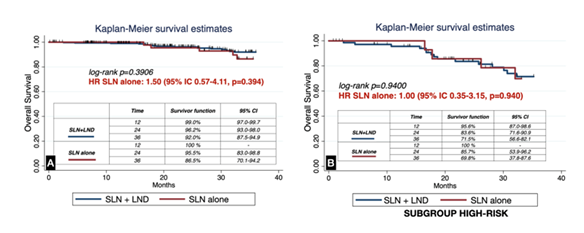

A summary of the main surgical, pathological, and oncologic outcomes after propensity score matching is presented in Table 4. Compared with the SLN+LND group, patients undergoing SLN biopsy alone had a significantly shorter hospital stay (2.1 (SD 1.0) vs 1.1 (SD 0.6), p<0.001) and markedly reduced rates of lymphadenectomy (45.3% vs 0.9%, p<0.001), with no significant differences in perioperative hemoglobin drop (2.05 (SD 0.9) vs 1.84 (SD 0.8), p=0.065) . SLN alone showed higher three-zone detection (67.0% vs 53.2%; p=0.003). Aortic and bilateral pelvic detection were similar or numerically higher with SLN alone (p=0.086 and p=0.050, respectively), without reaching statistical significance in the primary matched analysis. There were no statistically significant differences in PFS (log-rank p=0.0897) or OS (p=0.3906), including among preoperative high-risk patients (p=0.4420 and p=0.9400, respectively). Point estimates favored SLN+LND, a pattern compatible with residual confounding and/or limited power rather than a proven disadvantage of SLN (Table 4).

Table 4: Summary of surgical, pathological, and oncologic outcomes after propensity score matching.

|

Outcome |

SLN + LND (n=327) |

SLN alone (n=112) |

p |

||

|

Continuous (□, σ) |

|||||

|

Hospital stay (days) |

2.1 ± 1.0 |

1.1 ± 0.6 |

0.001 |

||

|

Hemoglobin drop (g/dL) |

2.05 ± 0.9 |

1.84 ± 0.8 |

0.065 |

||

|

Binary (n, %) |

|||||

|

Lymphadenectomy performed |

148 (45.3%) |

1 (0.90%) |

0.001 |

||

|

Aortic SLN detection |

222 (67.9%) |

89 (79.5%) |

0.086 |

||

|

Bilateral pelvic SLN detection |

229 (70.0%) |

93 (83.0%) |

0.05 |

||

|

Three-zone detection (pelvic + aortic) |

174 (53.2%) |

75 (67.0%) |

0.003 |

||

|

Survival 36 months (%; IC95) |

|||||

|

Progression-Free Survival (PFS) |

90.7% (86.3-93.7) |

78.8% (62.3-88.7) |

0.09 |

||

|

PFS, high-risk subgroup |

74.9% (61.5-84.2) |

59.7% (30.6-79.8) |

0.442 |

||

|

Overall Survival (OS) |

92.0% (87.5-94.9) |

86.5% (70.1-94.2) |

0.391 |

||

|

OS, high-risk subgroup |

71.5% (56.6-82.1) |

69.8% (37.8-87.6) |

0.94 |

||

Abbreviations: SLN = sentinel lymph node; LND = lymphadenectomy; PFS = progression-free survival; OS = overall survival; Three-zone detection = bilateral pelvic detection plus para-aortic detection. Data presented after neighbor (3:1) method for propensity score matching.

During follow-up, no significant differences were observed in progression-free survival (PFS) between groups (log-rank p=0.0897; HR for SLN alone, 1.90; 95% CI 0.89–4.04, p=0.095). Similarly, when restricted to patients with preoperative high-risk features, PFS remained comparable (log-rank p=0.4420; HR 1.40; 95% CI 0.56–3.73, p=0.445; Figure 2). Overall survival (OS) was also not significantly different between SLN alone and SLN+LND (log-rank p=0.3906; HR 1.50; 95% CI 0.57–4.11, p=0.394), including in the subgroup of high-risk patients (log-rank p=0.9400; HR 1.00; 95% CI 0.35–3.15, p=0.940; Figure 3). The median follow-up, estimated by reverse Kaplan–Meier, was 36.9 months (95% CI 34.4–39.9) overall for OS and 34.9 months (95% CI 31.5–37.1) for PFS. Stratified by treatment group, median OS follow-up was 36.7 months (95% CI 32.1–40.2) in the SLN+LND cohort and 37.1 months (95% CI 32.9–41.3) in the SLN-alone cohort. For PFS, median follow-up was 34.9 months (95% CI 29.6–37.3) and 35.3 months (95% CI 31.3–38.7), respectively.

Discussion

In this propensity score–matched cohort of 448 patients with endometrial carcinoma, we found that sentinel lymph node (SLN) biopsy alone achieved comparable oncologic outcomes to systematic lymphadenectomy (LND) while significantly reducing surgical morbidity. Patients in the SLN group had a shorter hospital stay and a non-significant trend toward lower perioperative blood loss. Detection rates of sentinel lymph node were at least equivalent among both groups—indeed, three-zone detection was significantly higher in the SLN alone group compared to the SLN+lymphadenectomy. Finally, considering cancer prognosis, no differences in progression-free survival (PFS) or overall survival (OS) were observed, even among patients with preoperative high-risk features. Interestingly, although not statistically significant, PFS estimates were numerically lower in the SLN alone group compared to SLN+LND. This pattern deserves attention, as it might reflect residual confounding or limited sample size rather than true biological differences, and highlights the need for cautious interpretation.

Our results are consistent with the FIRES trial and subsequent studies validating the diagnostic accuracy and negative predictive value of SLN mapping in endometrial cancer. In FIRES, sentinel node mapping achieved an overall detection rate of 86% and bilateral detection of 52%, with a sensitivity of 97.2%, specificity of 99.6%, negative predictive value (NPV) of 99.6%, and a false-negative rate of only 2.8% when compared with systematic lymphadenectomy [6]. Similarly, in our prospective 6-year study using dual cervical and fundal injection, we reported an overall detection rate of 95%, bilateral pelvic detection of 77%, and aortic detection of 67%, with a sensitivity of 96.3%, specificity of 100%, NPV of 99%, and positive predictive value of 100% [18]. These concordant findings across independent cohorts reinforce the robustness of SLN mapping as a staging strategy and support its safety and reproducibility in routine European practice. The SENTOR study and more recent European cohorts have also confirmed that SLN mapping is safe in intermediate- and high-grade histologies [7,16,22]. Not only SLN has proven to be safe, but in some studies its addition to systematic lymphadenectomy has also shown statistically improved overall survival compared to lymphadenectomy alone [23]. More recently, Ignatov et al. reported comparable oncologic outcomes with robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic SLN biopsy, reinforcing its safety profile [24]. Similarly, Makroum et al. found no significant survival differences between SLN and complete LND in a Japanese cohort [25], while Nasioudis et al. showed that SLN sampling may not compromise survival even in stage IIIC disease [26]. Although the numerical trend in our study suggested lower PFS in the SLN-alone group, this finding should be interpreted with caution. In principle, the shorter accrual window of the SLN cohort (2020 onwards) would be expected to underestimate late recurrences and therefore bias results in favor of SLN. The fact that the opposite pattern was observed likely reflects the occurrence of a few early recurrences in a relatively small sample, which can markedly influence survival estimates when the overall number of events is low. In such settings, random variation can generate apparent differences that are not statistically significant and should not be overinterpreted. This underscores the need for larger, adequately powered studies with longer follow-up to definitively clarify oncologic equivalence between both strategies.

The present study adds to this body of evidence by providing one of the largest real-world European cohorts analyzed to date, with standardized ultrastaging protocols and robust statistical adjustment through 3:1 propensity score matching. Importantly, the consistency of our findings across all matching strategies tested further reinforces the robustness of the results. This approach not only reduces treatment-selection bias but also approximates the methodological rigor of a randomized trial, offering clinically meaningful insights in a setting where randomized data remain scarce. By bridging the gap between controlled trials and routine practice, our findings contribute valuable external validity and help define the role of SLN biopsy as a standard staging strategy in endometrial cancer.

The use of dual-site ICG injection in our cohort likely contributed to the high detection rates, particularly in the para-aortic region, aligning with emerging evidence that dual mapping improves upper pelvic and infrarenal nodal identification. Our own prospective series have shown that combining cervical and fundal injection increases para-aortic SLN detection and is reproducible in clinical practice [18]. Similar findings have been reported by Torrent et al., who demonstrated higher para-aortic mapping with dual-site dual-tracer injection [27], and by Gezer et al., who observed significantly improved para-aortic detection with transcervical fundal injection compared to cervical injection alone [28]. Capozzi and colleagues, in their study, highlighted that extending injection beyond the cervix can optimize upper basin mapping [16]. In addition, Kim et al. recently described a two-step approach in a Korean cohort: tracer is first injected into the fundus to identify para-aortic SLNs, and subsequently into the cervix to target pelvic mapping [29]. Collectively, these data suggest that dual-site injection is a simple yet effective refinement that may further strengthen the case for SLN as a stand-alone staging approach.

The strengths of our study include its large single-institution cohort, standardized surgical protocol with lymph node ultrastaging, and rigorous PSM methodology. Nevertheless, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the retrospective, single-center design may limit external validity. Second, although follow-up was adequate and similar across groups, the SLN-alone cohort began in 2020, resulting in a shorter observation window despite comparable reverse Kaplan–Meier estimates for OS and PFS; this may underestimate late recurrences. Third, morbidity outcomes were restricted to length of stay and perioperative hemoglobin drop, without systematic assessment of long-term complications such as lymphedema or lymphocele. Fourth, molecular tumor profiling was not consistently available across the study period, which may have introduced residual imbalances in prognostic subgroups despite adequate matching. In addition, small discrepancies in sample size across outcomes were explained by occasional missing values in some variables; given their low frequency, these missing data are unlikely to have materially affected the analyses. Finally, although PSM achieved good balance (SMD <10% for all covariates), residual confounding from unmeasured variables cannot be excluded.

Taken together, our findings support the use of SLN biopsy alone as a safe and less invasive alternative to systematic LND in patients with early-stage endometrial cancer, including selected high-risk cases. Longer follow-up and prospective randomized trials remain necessary to confirm oncologic equivalence and to define the role of SLN mapping in advanced and high-grade disease. Although our results are consistent with previously published series showing comparable oncologic outcomes between SLN and LND, the trend towards slightly worse PFS in the SLN group—albeit non-significant—aligns with findings reported elsewhere and underscores the urgent need for larger, ideally multicenter prospective trials to definitively clarify these outcomes. Importantly, future studies should also integrate molecular tumor profiling, given its growing impact on risk stratification and treatment tailoring in endometrial cancer. Ongoing randomized trials would greatly benefit from protocol amendments to incorporate molecular classification as a prespecified variable, ensuring that surgical strategies are evaluated within the contemporary framework of molecularly defined subgroups. Moreover, although no formal cost-effectiveness analysis was performed in our study, the reduction in hospital stay and morbidity suggests potential clinical and economic advantages that should be confirmed in future research. Together, these aspects highlight how SLN biopsy, coupled with molecular stratification and economic considerations, should define the next generation of clinical trials and guideline recommendations in endometrial cancer.

Conclusions

Sentinel lymph node biopsy, performed with dual-site indocyanine green injection, offers equivalent oncologic safety to systematic lymphadenectomy while significantly reducing surgical morbidity in endometrial cancer staging. These findings provide strong real-world evidence to support SLN biopsy as a standard staging approach in appropriately selected patients. Prospective studies with longer follow-up are warranted to confirm oncologic equivalence, particularly in high-risk subgroups. Integration of molecular classification will be essential to tailor surgical staging strategies in the contemporary management of endometrial cancer, and these results may support future European guideline recommendations.

Conflicts of Interest:

None declared.

CRediT authorship contribution statement:

MG: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration; MH: Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing; MR: Data curation, Writing – review & editing; MI: Methodology, Formal análisis; NM: Writing – original draft , Writing – review & editing; RRS: Writing – review & editing; JC: Writing – review & editing; IJ: Writing – review & editing; PC: Writing – review & editing; AL: Supervision, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

|

Author |

CRediT Roles |

|

Mikel Gorostidi, MD, MSc, PhD |

Conceptualization; Methodology; Software; Validation; Formal analysis; Investigation; Data curation; Writing – original draft; Visualization; Supervision; Project administration |

|

Marta Heras, MD |

Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing |

|

Mar Rubio, MD, PhD |

Data curation; Writing – review & editing |

|

Mª Teresa Iglesias, MSc, PhD |

Methodology; Formal analysis |

|

Nabil Manzour, MD |

Writing – original draft; Writing – review & editing |

|

Rubén Ruiz Sautua, MD |

Writing – review & editing |

|

Juan Céspedes, MD |

Writing – review & editing |

|

Ibon Jaunarena, MD |

Writing – review & editing |

|

Paloma Cobas, MD |

Writing – review & editing |

|

Arantxa Lekuona, MD (Chief of Department) |

Supervision; Resources; Writing – review & editing |

Funding:

No external funding received for this study.

References

- Amant F, Mirza MR, Koskas M, et al. Cancer of the corpus uteri. Int J Gynecol Obstet [Internet]. 2018 Oct [cited 2019 Apr 1];143: 37-50. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1002/ijgo.12612

- Lindqvist E, Wedin M, Fredrikson M, et al. Lymphedema after treatment for endometrial cancer − A review of prevalence and risk factors. Vol. 211, European Journal of Obstetrics Gynecology and Reproductive Biology (2017).

- Helgers R ~J. ~A., Winkens B, Slangen B ~F. ~M., et al. Lymphedema and Post-Operative Complications after Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy versus Lymphadenectomy in Endometrial Carcinomas—A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med 10 (2021):120.

- Leitao MMJ, Zhou QC, Gomez-Hidalgo NR, et al. Patient-reported outcomes after surgery for endometrial carcinoma: Prevalence of lower-extremity lymphedema after sentinel lymph node mapping versus lymphadenectomy. Gynecol Oncol 156 (2020): 147-153.

- Bjørnholt SM, Groenvold M, Petersen MA, et al. Patient-reported lymphedema after sentinel lymph node mapping in women with low-grade endometrial cancer. Am J Obstet Gynecol 232 (2025): 306.e1-306.e11.

- Rossi EC, Kowalski LD, Scalici J, et al. A comparison of sentinel lymph node biopsy to lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer staging (FIRES trial): a multicentre, prospective, cohort study. Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2017;18(3):384–92. Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30068-2

- Cusimano MC, Vicus D, Pulman K, et al. Assessment of Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy vs Lymphadenectomy for Intermediate- and High-Grade Endometrial Cancer Staging. JAMA Surg 156 (2021): 157-164.

- Glaser G, Dinoi G, Multinu F, et al. Reduced lymphedema after sentinel lymph node biopsy versus lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 31 (2021): 85-91.

- Burke TW, Levenback C, Tornos C, et al. Intraabdominal lymphatic mapping to direct selective pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy in women with high-risk endometrial cancer: results of a pilot study. Gynecol Oncol 62 (1996): 169-173.

- Lopes L ~A. ~F., Nicolau S ~M., Baracat F ~F., et al. Sentinel lymph node in endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 17 (2007): 1113-1117.

- Frumovitz M, Bodurka DC, Broaddus RR, et al. Lymphatic mapping and sentinel node biopsy in women with high-risk endometrial Gynecol Oncol 104 (2007): 100-103.

- Ballester M, Dubernard G, Lécuru F, et al. Detection rate and diagnostic accuracy of sentinel-node biopsy in early stage endometrial cancer: A prospective multicentre study (SENTI-ENDO). Lancet Oncol [Internet]. 2011 May [cited 2019 Nov 12]; 12 (2019): 469-476. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21489874

- How JA, O’Farrell P, Amajoud Z, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping in endometrial cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Minerva Ginecol [Internet]. 2018 Apr [cited 2019 Nov 16]; 70 (2018): 194-214. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/29185673

- Holloway RW, Abu-Rustum NR, Backes FJ, et al. Sentinel lymph node mapping and staging in endometrial cancer: A Society of Gynecologic Oncology literature review with consensus recommendations. Gynecol Oncol [Internet]. 2017 Aug [cited 2019 Nov 16]; 146 (2): 405-415. Available from: https://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0090825817308831

- Kitchener H, Swart AMC, Qian Q, et al. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet (London, England) 373 (2009): 125-136.

- Capozzi VA, Rosati A, Maglietta G, et al. Long-term survival outcomes in high-risk endometrial cancer patients undergoing sentinel lymph node biopsy alone versus lymphadenectomy. Int J Gynecol cancer Off J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc 33 (2023): 1013-1020.

- Ruiz R, Gorostidi M, Jaunarena I, et al. Sentinel node biopsy in endometrial cancer with dual cervical and fundal indocyanine green injection. Int J Gynecol Cancer. (2018).

- Gorostidi M, Ruiz R, Cespedes J, et al. Aortic sentinel node detection in endometrial cancer: 6 year prospective study. J Gynecol Obstet Hum Reprod 52 (2023): 102584.

- Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endmetrium. Vol. 105, International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. United States; (2009): p. 103-104.

- Austin PC. Optimal caliper widths for propensity-score matching when estimating differences in means and differences in proportions in observational studies. Pharm Stat 10 (2011): 150-161.

- Ojeda D, Leiva V, Vidal C, Sanhueza A. ¿Qué son las puntuaciones de propensión? Rev Med Chil [Internet]. 2016; 144 (3): 373-382. Available from: https://www.scielo.cl/scielo.php?pid=S0034-98872016000300012&script=sci_arttext

- Persson J, Salehi S, Bollino M, et al. Pelvic Sentinel lymph node detection in High-Risk Endometrial Cancer (SHREC-trial)-the final step towards a paradigm shift in surgical staging. Eur J Cancer 116 (2019): 77-85.

- Kogan L, Matanes E, Wissing M, et al. The added value of sentinel node mapping in endometrial cancer. Gynecol Oncol 158 (2020): 84-91.

- Ignatov A, Mészáros J, Ivros S, et al. Oncologic Outcome of Robotic-Assisted and Laparoscopic Sentinel Node Biopsy in Endometrial Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 15 (2023).

- Makroum AA, Lee YJ, Lee J-Y, et al. Comparison of oncological outcomes between sentinel lymph node biopsy and complete lymphadenectomy for endometrial cancer. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 49 (2023): 2118-2125.

- Nasioudis D, Byrne M, Ko EM, et al. The impact of sentinel lymph node sampling versus traditional lymphadenectomy on the survival of patients with stage IIIC endometrial cancer. Int J Gynecol cancer Off J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc 31 (2021): 840-845.

- Torrent A, Amengual J, Sampol CM, et al. Sentinel Lymph Node Biopsy in Endometrial Cancer: Dual Injection, Dual Tracer-A Multidisciplinary Exhaustive Approach to Nodal Staging. Cancers (Basel) 14 (2022).

- Gezer S, Tokgozoglu N, Simsek T, et al. Cervical versus endometrial tracer injection for sentinel lymph node detection in endometrial cancer: impact on para-aortic mapping. Int J Gynecol Cancer 34 (2024): 227–234.

- Eoh KJ, Lee YJ, Kim H-S, et al. Two-step sentinel lymph node mapping strategy in endometrial cancer staging using fluorescent imaging: A novel sentinel lymph node tracer injection procedure. Surg Oncol [Internet]. 2018 Sep [cited 2019 Jan 21]; 27 (3): 514-519. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/30217312

Supplementary Data

Supplementary Appendix: Propensity Score Assumptions, Balance Assessment, and Robustness Checks

This supplementary material provides additional methodological details and analyses supporting the propensity score matching procedure. It includes assessment of the common support assumption (overlap), balance diagnostics under different matching strategies and justification for the selection of the 3:1 nearest-neighbor method. These robustness checks confirm the validity and consistency of the main study findings

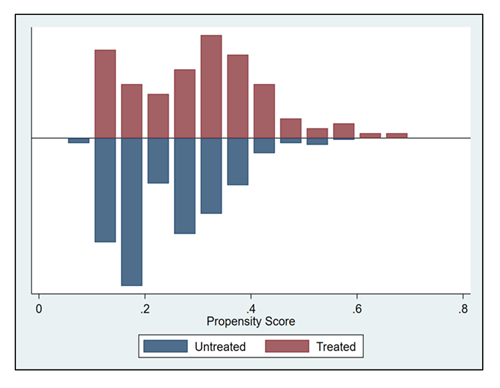

To assess fulfillment of the “area of common support” (overlap) assumption, the figure below depicts the distribution of propensity scores across groups. The x-axis shows the estimated propensity score values. A limited number of patients fall outside the region of common support, which explains the small reduction in the final matched sample. In addition, patients treated with SLN+LND tended to present higher propensity scores compared with those treated with SLN alone.

To select the optimal matching strategy, we compared different methods and evaluated both the mean and median standardized bias across all outcomes. The 3:1 nearest-neighbor method consistently achieved the lowest imbalance, which justified its use as the primary approach in the present study. It is important to note that this procedure does not estimate the treatment effect itself. As required by Stata SE, an outcome variable must be specified when running the command for this calculation. For transparency, we performed the assessment across all outcomes of interest to confirm that the results were consistent regardless of the outcome selected.

Table 1S summarizes the mean and median standardized bias before and after matching for different strategies (1:1 nearest neighbor, caliper 0.2, and 3:1 nearest neighbor). While all methods substantially reduced imbalance compared with the unmatched cohort, the 3:1 nearest-neighbor approach consistently achieved the lowest mean and median bias across all outcomes. These results support the selection of 3:1 nearest-neighbor matching as the primary method in the present analysis.

|

OUTCOME |

Neighbor (1:1) |

Caliper (0.2) |

Neighbor (3:1) |

||||

|

Mean Bias |

Median |

Mean Bias |

Median |

Mean Bias |

Median |

||

|

Bias |

Bias |

Bias |

|||||

|

Hospitalization (days) |

Unmatched |

14.5 |

9.6 |

14.5 |

9.6 |

14.5 |

9.6 |

|

Matched |

6.7 |

5.1 |

6.7 |

5.1 |

3.6 |

3.7 |

|

|

Hemoglobin drop (Hb) |

Unmatched |

14.6 |

11.5 |

14.6 |

11.5 |

14.6 |

11.5 |

|

Matched |

7.1 |

5 |

7.1 |

5 |

3.1 |

2.9 |

|

|

Lymphadenectomy |

Unmatched |

14.8 |

10.8 |

14.8 |

10.8 |

14.8 |

10.8 |

|

Matched |

7 |

5.7 |

7 |

5.7 |

3.5 |

5.1 |

|

|

Aortic |

Unmatched |

15.1 |

10.7 |

15.1 |

10.7 |

15.1 |

10.7 |

|

detection |

Matched |

6.6 |

5.2 |

6.6 |

5.2 |

3.6 |

4 |

|

Bilateral pelvic detection |

Unmatched |

14.7 |

10.5 |

14.7 |

10.5 |

14.7 |

10.5 |

|

Matched |

7.2 |

5.2 |

7.2 |

5.2 |

3.3 |

4.4 |

|

|

Three-zone detection |

Unmatched |

14.8 |

10.8 |

14.8 |

10.8 |

14.8 |

10.8 |

|

Matched |

7 |

5.7 |

7 |

5.7 |

3.5 |

5.1 |

|

Table 1S: Mean and median standardized bias before and after matching using different strategies (1:1 nearest neighbor, caliper 0.2, and 3:1 nearest neighbor). All methods improved balance compared with the unmatched cohort, but the 3:1 nearest-neighbor approach consistently achieved the lowest bias across outcomes.

Impact Factor: * 3.2

Impact Factor: * 3.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.63%

Acceptance Rate: 76.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks