The live birth rate improved when the endometrial thickness decreased from the HCG day to the embryo transfer day. A retrospective cohort study of 9572 fresh embryo transfer cycles

Miao Wang1, Xinglin Wang1, Ying Meng1, Fang Wang1, Hong Ye1*

1 Chongqing Health Center for Women and Children, Women and Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical

University, Chongqing, China

*Corresponding Author: Hong Ye, Chongqing Health Center For Women and Children, Women and Children's Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China

Received: 13 February 2023; Accepted: 16 February 2023; Published: 08 March 2023

Article Information

Citation: Miao Wang. The live birth rate improved when the endometrial thickness decreased from the HCG day to the embryo transfer day. A retrospective cohort study of 9572 fresh embryo transfer cycles. Obstetrics and Gynecology Research. 6 (2023): 100-106

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Aim:

To investigate whether decreased endometrial thickness from the HCG trigger day to the embryo transfer day affects the pregnancy outcomes of IVF/ICSI cycles.

Methods:

A retrospective single-center cohort study was conducted. In total, 9572 first IVF/ICSI embryo transfer cycles involving the long protocol at Chongqing Reproductive and Genetic Institute from January 1, 2016, to June 30, 2020were included. The 9572 cycles were divided into 2 groups based on whether the endometrial thickness decreased from the HCG trigger day to the embryo transfer day. The outcomes of the two groups were compared. The primary outcome was live birth rate (LBR). The secondary outcomes were clinical pregnancy rate (CPR), pregnancy loss rate (PLR) and ectopic pregnancy rate (EPR).

Results:

The LBR of participants in the decreased endometrial thickness group was higher than that in the non-decreased group (54.26% vs. 51.67%, P=0.023, after adjusting the confounding factors P=0.032), and the CPR in the decreased group was also higher than that in the non-decreased group (61.36% vs. 58.88%, P=0.027, after adjusting confounding factors P=0.037). There was no significant difference in the EPR (1.65%vs. 1.82%, P = 0.513) or pregnancy loss rate (6.85%vs. 7.42% P = 0.771) between two groups.

Conclusions:

A properly decreased of endometrial thickness from the HCG trigger day to the embryo transfer day in IVF/ICSI cycles will increases the LBR and CPR. Therefore, the decreased endometrial thickness from the HCG trigger day to the embryo transfer day cannot be the determined factor of cancelling embryo transfer.

Keywords

<p>In Vitro Fertilization; Endometrial Thickness, Ultrasound, Progesterone</p>

Article Details

Abbreviations

HCG: Human Chorionic Gonadotropin; IVF: In Vitro Fertilization; ICSI: Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection; LBR: Live Birth Rate; CPR: Clinical Pregnancy Rate; PLR: Pregnancy Loss Rate; EPR: Ectopic Pregnancy Rate; GnRH-a: Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone Agonist; AMH: Antimullerian Hormone; BMI: Body Mass Index; OHSS: Ovarian Hyperstimulation Syndrome; VEGF: Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor

INTRODUCTION

Previous studies suggested that pregnancy outcome is closely related to endometrial thickness [12]. KE Liu reported that the clinical pregnancy rate declined with the poor endometrial thickness within a certain range [3]. Therefore, we often measured endometrial thickness using transvaginal ultrasound before embryo transfer. Most of doctors decided to cancel the embryo transfer when endometrial thickness is less than 7 or 8 mm. However, we found that endometrial thickness changed between the HCG trigger day and embryo transfer day in this study. In some cases, the endometrial thickness decreased after the HCG trigger, while in others, it remained the same or continued to thicken. Does this mean that the current embryo transfer cycle should be cancelled for patients with decreasing endometrial thickness? Jokubkiene reported that sub-endometrial vascularization changes markedly during the normal menstrual cycle. It increased throughout the follicular phase, decreased to a nadir 2 days after ovulation and then increased again during the luteal phase [4]. Does a slight decrease in endometrial thickness during the stimulation cycle means changes in sub-endometrial blood vessels, and does this change affects the outcomes of embryo implantation? With these questions, we explored in this study whether the decreasing endometrial thickness from the HCG trigger day to the embryo transfer day would affect pregnancy outcomes.

Materials and methods

Data preparation

The data of 9572 IVF/ICSI embryo transfer cycles carried out with long gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) protocol stimulation at Chongqing Reproductive and Genetics Institute were obtained from January 1, 2016, to June 30, 2020. Trials were considered for inclusion with the following criteria: (1) participants who underwent controlled ovarian stimulation (COS) with the long GnRH-a protocol; (2) patients who registered for fresh embryo transfer cycles; and (3) cases who had their first IVF/ICSI cycles. Exclusion criteria: (1) age over 40 years; (2) endometrial thickness <7 mm on embryo transfer day; and (3) blastocyst transfer cycles.

Ovarian stimulation protocol and embryo transfer strategy

Patients with long protocol were treated with GnRH-a to downregulate the functions of the pituitary gland on the day 21 of the previous menstrual cycle. After downregulation of the pituitary gland, gonadotropin was initiated with a starting dose of recombinant FSH ranging from 112.5 to 300 IU, and gonadotropin was modulated according to the patient’s ovarian response. Recombinant HCG (250 µg, Merck Serono) were used to trigger ovulation in all cases after at least two mature follicles were observed to reach 18 mm. The oocytes were retrieved 34-36 hours after the HCG trigger, and progesterone gel (90 mg, Crinone 8%, Merck Serono) was administered vaginally on the day of egg collection. Embryo transfer was performed 3 days after oocyte retrieval and the usual IVF or ICSI procedure. Endometrial thickness was measured in the morning on both the HCG day and the transfer day. In our center, three doctors specializing in vaginal ultrasound measurement performed this work. They underwent unified ultrasonic measurement training. The coefficient variation of the measurement results obtained by the different doctors was less than 5%.After embryo transfer , the vaginal progesterone gel was continued for luteal support. Venous blood-HCG levels were measured 14 days after embryo transplantation. Transvaginal ultrasonography of the uterus was performed 4 weeks after embryo transplantation.

Outcomes and definitions

The primary outcome was live birth rate. The secondary outcomes were clinical pregnancy rate, pregnancy loss rate and ectopic pregnancy rate. Live birth was defined as delivery of any neonate after 28 weeks of gestation. Clinical pregnancy was defined as a viable pregnancy with fetal heart activity under ultrasonography. Ectopic pregnancy was defined as the detection of a gestational sac outside the uterus. Pregnancy loss was defined as the spontaneous loss of the embryo or fetus before 28 weeks of gestation.

Statistical analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Science software (version 24, SPSS Inc., Chicago. IL, USA) was used to analyze data in this study. Continuous variables are expressed as the mean ± SD. The 9572 cycles were divided into two groups based on whether their endometrial thickness was decreased. Decreased group: the endometrial thickness on embryo transfer day was thinner than that on the HCG day (n = 2663).Non-decreased group: the endometrial thickness on the embryo transfer day was equal to or thicker than that on the HCG day (n = 6909). Student’s t-test was used to detect differences between continuous variables, and the chi-square test was used for categorical variables. Categorical variables are presented as the number of cases (n) and the percentage (%). Binomial logistic regression analysis was used to adjust for the baseline characteristics between the two groups. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

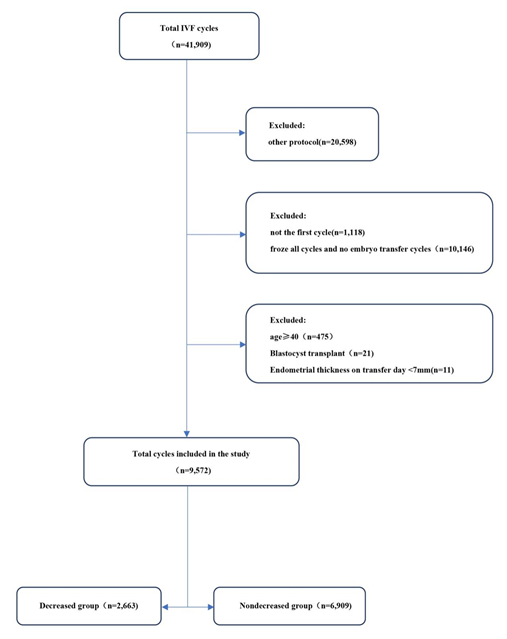

A total of 41,909 cycles were screened and assessed. Finally, a total of 9572 patients with the first IVF/ICSI cycle and met the study eligibility criteria, among that, 2663 patients in the decreased group and 6909 patients in the non-decreased group (Figure 1). The demographic characteristics were shown in Table 1. There were significant differences in patients' age (30.87±3.82 vs. 31.05±3.79 years, P=0.044), and AMH was higher in the decreased group (3.07±2.45 vs. 2.96±2.27, P=0.039). There was no significant difference in BMI, infertility type or infertility reason between the two groups.

The duration of ovarian stimulation (days) in the decreased group was greater than that in the non-decreased group (10.84± 1.33 vs. 10.70±1.34, P< 0.001). There was no significant difference between the two groups with regard to estradiol on the trigger day, progesterone on the trigger day, total dose of gonadotropin, number of oocytes retrieved, fertilization type or top-quality embryos (Table 2).

The clinical outcomes in the two groups are shown in Table 3. After adjusting for potential confounders, including age, anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH), duration of ovarian stimulation (days), binomial logistic regression analysis demonstrated that there was significant difference in the live birth rate (54.26% vs. 51.67%, P=0.023, after adjusting for confounding factors P=0.032) and the clinical pregnancy rate (61.36% vs. 58.88%, P=0.027, after adjusting for confounding factors P=0.037). However, there were no significant difference in the ectopic pregnancy rate (1.65%vs. 1.82%, P=0.569, after adjusting for confounding factors P= 0.513) or the pregnancy loss rate (6.85%vs. 7.42%, P= 0.722, after adjusting for confounding factors, P = 0.771) (Table 3).

Figure 1: Flow chart of the patients’ allocation

Discussion

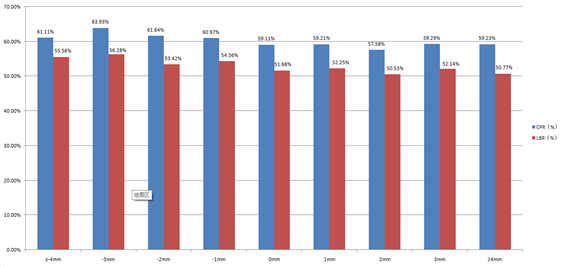

In this study, we found that the endometrial thickness after HCG trigger is not invariable. It can also be seen from Figure 2 that the pregnancy outcome changed with the reduction of endometrial thickness. It seems that when endometrial thickness reduction, the CPR and LBR do not decrease but tend to increase.This conclusion is consistent with that of study conducted by Jigal Haas [5].

Figure 2: CPR and LBR among groups with different endometrial changes

|

|

Decreased group (n=2663) |

Nondecreased group (n=6909) |

P |

|

Age(years) |

30.87±3.82 |

31.05±3.79 |

0.044* |

|

Infertility years(years) |

5.091±3.66 |

5.03±3.57 |

0.453 |

|

BMI |

22.01±2.75 |

22.01±2.80 |

0.951 |

|

AMH |

3.07±2.45 |

2.96±2.27 |

0.039* |

|

Infertility type |

|

||

|

Primary infertility%(n) |

44.09% (1174) |

43.80% (2998) |

0.540 |

|

Secondary infertility%(n) |

55.91% (1489) |

56.20% (3911) |

0.540 |

|

Infertility reason |

|

||

|

Tubal factor%(n) |

78.67% (2095) |

79.42% (5487) |

0.419 |

|

Endometriosis%(n) |

0.86%(23) |

0.91%(63) |

0.823 |

|

Male factor%(n) |

9.13%(243) |

8.57%(592) |

0.387 |

|

Multiple factors%(n) |

6.27%(167) |

6.37%(440) |

0.861 |

|

Unexplained infertility%(n) |

5.07%(135) |

4.73%(327) |

0.491 |

*Statistically significant P-value < 0.05

Table 1: Characteristics of the basic parameters of patients in the two groups

Jokubkiene studied the changes in endometrial blood flow in 14 volunteers during the natural cycle and found that during the follicular phase, the sub-endometrial blood vessel index increased with follicular growth and that the thickness and volume of the endometrium increased rapidly. The sub-endometrial blood vessel index decreased to the lowest point 2 days after ovulation and then increased again during the luteal phase [4]. This finding seems to explain the decrease in endometrial thickness during the stimulation cycle between the HCG trigger day and the embryo transfer day. We hypothesize this endometrial change is very similar with that of in the natural cycle, which might contribute to improving endometrial receptivity. Sarani SA proposed that 1 to 5 days after ovulation is the period of the menstrual cycle when endometrial vascularization is at its lowest, and it is also the period when endometrial receptivity is thought to be at its maximum in terms of hypoxia [6]. It has been demonstrated in animal studies that near-atmospheric oxygen concentrations reduce embryo viability and compromise embryo development and that oxygen tension in the uterus is lowest during the implantation period [7-8]. Popovici RM suggested that endometrial hypoxia stimulates the production of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) in endometrial stromal cells [9]. Tsuzuki T reported that hypoxic stress stimulates the generation of VEGF through hypoxia-inducing factor-1 [10]. The increase in VEGF in turn regulates the angiogenesis of the endometrium and stimulates further growth of the endometrium [11]. In a single-center retrospective control study, Zhiqin Bu found that an increased endometrial thickness after progesterone administration was associated with better pregnancy outcomes for thawed blastocyst cycles [12]. The possible reason for this conflicting result is that all of our research objects involved cleavage-stage embryo transfer, with the transfer period being in the early luteal phase, in contrast to that of the blastocyst transfer, which is closer to the middle luteal phase. In addition, the effects of high estrogen levels on the endometrium during stimulation cycles may lead to different results.

We assume that the transformation of the endometrium from the hyperplasia stage to the secretion stage is accompanied by a decrease in the vascularization degree and uterine thickness, which leads to a decrease in the endometrial oxygen concentration. Hypoxic stress stimulates the expression of VEGF through hypoxia-inducing factor-1, which leads to an increase in the endometrial vascularization degree and further stimulates the endometrium to thicken again. The reason why this change is not obvious on ultrasound is that the endometrial thickness during the luteal phase changes within a small range. Even so, different patterns of changes in endometrial thickness within a small range were associated with different pregnancy outcomes. In addition, in our study, we found that the endometrium continued to thicken in some patients from the HCG trigger day to the embryo transfer day. Does the endometrium in this population continue to thicken due to exogenous progesterone deficiency or endogenous progesterone deficiency? According to Usadi et al., this process is independent of the actual circulating progesterone concentration; whether serum progesterone levels are normal or abnormally low, secretory endometrial development is similar [13]. According to Yoo J, some infertile women have defects in progesterone receptor or endometrial resistance, and the related reasons include overexpression of bcl-6 and sirt-1[14], chronic endometrial inflammation, progesterone receptor gene polymorphism, altered microRNA expression, and epigenetic modification of the progesterone receptor [15,16]. Another theory is that the ratio of estrogen to progesterone plays a role, with too much estrogen causes the endometrium to continue to grow. This conjecture may also explain why the endometrial receptivity of fresh embryo transplantation during the ovulatory cycle is lower than that during freeze-thaw embryo transplantation [17]. Since patients who retrieved more than 20 oocytes in our center would receive whole embryo cryopreservation, we cannot analyze the pregnancy outcome after fresh embryo transfer for patients with this type of super-estrogen level, so we cannot confirm its hypothesis. However, our data revealed that there was no significant difference between the two groups in terms of estrogen levels on the HCG trigger day and progesterone levels on the HCG trigger day. It may be suggested that the levels of estrogen and progesterone in cycles are not the main factors determined whether the endometrial thickness decreases. However, the expression of estrogen and progesterone receptors and related inflammatory factors may be the key factors.

|

|

Decreased group (n=2663) |

Non-decreased group (n=6909) |

P |

|

Estradiol on the trigger day(pmol/L) |

3106.31±1188.04 |

3067.96±1282.35 |

0.166 |

|

Progesterone on the trigger day(ng/mL) |

0.518±0.280 |

0.522±0.284 |

0.492 |

|

Duration of ovarian stimulation (days) |

10.84±1.33 |

10.70±1.34 |

0.000* |

|

Total dose of gonadotropin (IU) |

2386.83±762.37 |

2369.21±738.80 |

0.3 |

|

No. of oocytes retrieved |

10.05±3.90 |

9.97±3.93 |

0.329 |

|

Endometrial thickness on HCG day |

11.11±1.53 |

9.62±1.49 |

0.000 |

|

Endometrial thickness on transfer day |

9.63±1.41 |

10.58±1.65 |

0.000 |

|

Endometrial thickness change from HCG day to transfer day |

-1.48±0.76 |

0.96±1.03 |

0.000 |

|

Fertilization type |

|

||

|

IVF%(n) |

83.59%(2226) |

84.05%(5807) |

0.583 |

|

ICSI %(n) |

12.65%(337) |

12.64%(873) |

0.979 |

|

IVF+ICS I%(n) |

3.76%(100) |

3.31%%(229) |

0.289 |

|

No. of implanted embryos |

1.94±0.25 |

1.93±0.26 |

0.274 |

|

Top-quality embryos |

1.77±1.21 |

1.84±1.20 |

0.140 |

T-tests and chi-square tests were used* Statistically significant P-value < 0.05

Table 2: Treatment characteristics in the two groups

Top-quality embryos: All transferable embryos were assessed on day 2 or 3 for blastomere number and regularity as well as for the presence and volume of cytoplasmic fragmentation. Day 3 embryos with eight equal size cells,no cytoplasmic fragments, from Day 2 embryos with four equal size cells, no cytoplasmic fragments.

|

|

Decreased group (n=2663) |

Non-decreased group (n=6909) |

Before adjustment |

After adjustment |

||

|

95%CI |

P |

95%CI |

P |

|||

|

LBR%(n) |

54.26% (1445) |

51.67(3570) |

1.014~1.214 |

0.023* |

1.009~1.209 |

0.032* |

|

CPR %(n) |

61.36%(1634) |

58.88% (4068) |

1.109~1.012 |

0.027* |

1.006~1.210 |

0.037* |

|

EPR%(n) |

1.65%(44) |

1.82%(126) |

0.640~1.279 |

0.569 |

0.630~1.260 |

0.513 |

|

PLR%(n) |

6.85%(112) |

7.42%(302) |

0.770~1.199 |

0.722 |

0.775~1.209 |

0.771 |

*Statistically significant P-value < 0.05

Table 3: Clinical outcomes in the two groups

The advantage of this study lies in it’s the first relevant report on the effect of endometrial changes on live birth rate from HCG day to embryo transfer day. At the same time, this study has a large sample size and reliable results. In order to reduce the deviation of results caused by different ovulation stimulation program, we only studied long gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRH-a) protocol. At the same time, we conducted a logistic regression to adjust the confounding factors that may affect the pregnancy outcome. The results of this study are consistent with previous studies, indicating that endometrial thickness is an important factor affecting pregnancy outcome. Its innovative discovery is that, contrary to our previous conjecture, the reduction of endometrium in a few days from the HCG day to the embryo transfer day will not adversely affect the pregnancy outcome

The limits of this study include that above conclusions were obtained in the long protocol, and it is unknown whether the same conclusions were obtained in other protocol. As mentioned in Figure 1, we conducted a retrospective analysis of 41,909 cycles, and 20,598 of them were other protocol than the long protocol, so the long plan was not the only plan we used. And we found that the Cumulative live birth rates of GnRH-a group was higher than that of GnRH-ant group in suboptimal responders; no significant difference was observed in other patients between different protocols[18], which was the reason the long protocol become the mainstream program in our center. In addition, blastocyst embryos were not included in our study. Some studies suggested that extended culture may impact offspring via differences in gene expression and epigenetic mutations, particularly regarding the blastocyst stage [19-24]. Extending the duration of embryo culture to the blastocyst stage for assisted reproduction may decrease the number of embryos transferred. Patients who received assisted reproduction treatment in China pay for themselves and did not receive any government subsidies, so most of them were not willing to risk a reduction in the number of embryos transferred after blastocyst culture. Since there were few patients with blastocyst transplantation during the egg retrieval cycle in our center, which could not be analyzed as a single group, therefore, the study with the relevant population could be considered in the future. Meanwhile, it also remains to be seen that whether this hypothesis could be applied to freeze-thaw embryo transfer.

Conclusion

In summary, the endometrial thickness from the HCG trigger day to the embryo transfer day is not static in fresh embryo transfer cycle, and we cannot use the decreased endometrial thickness as determined factor to cancel the embryo transfer. In contrast, the decreased endometrial thickness may indicate a better pregnancy outcome.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The study has been approved by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing Maternal and Child Health Hospital. Approval reference number:(No.2019-1206) for retrospective analysis and clinical data reporting. Since the anonymous data were respectively extracted from the electronic record without any information that could identify particular individual, A waiver of informed consent was granted by the Institutional Review Board of Chongqing Health Center for Women and Children. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations (accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

The data sets analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Authors’ contributions

Miao W designed the study and drafted the manuscript. Xinlin W collected the data. Ying M contributed to the analysis and interpretation on data. Fang W contributed to the statistical analysis. Hong Y give the critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dr. Xiaodong Z and Jinwei Y for their assistance in the data analysis.

References

- Zhang Q , Li Z , Wang Y , et al (2021) The relationship and optimal threshold of endometrial thickness with early clinical pregnancy in frozen embryo transfer cycles[J]. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics..

- Fang T , Chen M , Yu W , et al (2021) The predictive value of endometrial thickness in 3117 fresh IVF/ICSI cycles for ectopic pregnancy. Journal of Gynecology Obstetrics and Human Reproduction 50(4): 102072.

- Liu K, Hartman M, Hartman A, Luo Z, Mahutte N (2018) The impact of a thin endometrial lining on fresh and frozen–thaw IVF outcomes: an analysis of over 40 000 embryo transfers. Hum Reprod33:1883-1888.

- Jokubkiene L, Sladkevicius P, Rovas L, Valentin L (2006) Assessment of changes in endometrial and subendometrial volume and vascularity during the normal menstrual cycle using threedimensional power Doppler ultrasound. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecology 27: 672-679.

- Haas J, Smith R, Zilberberg E, Nayot D, Meriano J, Barzilay E, Casper R (2019) Endometrial compaction (decreased thickness) in response to progesterone results in optimal pregnancy outcome in frozen-thawed embryo transfers. Fertility and Sterility 112: 503-509.e1.

- Sarani S, Ghaffari-Novin M, Warren M, Dockery P, Cooke I (1999) Morphological evidence for the `implantation window' in human luminal endometrium. HumReprod14: 3101-3106.

- Karagenc L, Sertkaya Z, Ciray N, Ulug U, Bahçeci M (2004) Impact of oxygen concentration on embryonic development of mouse zygotes. ReproductiveBioMedOnline 9:409-417.

- Fischer B, Bavister B (1993) Oxygen tension in the oviduct and uterus of rhesus monkeys, hamsters and rabbits. J ReprodFertil99: 673-679.

- Popovici R, Irwin J, Giaccia A, Giudice L (1999) Hypoxia and cAMP Stimulate Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) in Human Endometrial Stromal Cells: Potential Relevance to Menstruation and Endometrial Regeneration. JClin EndocrinolMetab84: 2245-2245.

- Tsuzuki T, Okada H, Cho H, Tsuji S, Nishigaki A, Yasuda K, Kanzaki H (2011) Hypoxic stress simultaneously stimulates vascular endothelial growth factor via hypoxia-inducible factor-1and inhibits stromal cell-derived factor-1 in human endometrial stromal cells. Hum Reprod 27: 523-530.

- Moller B, Lindblom B, Olovsson M (2002) Expression of the vascular endothelial growth factors B and C and their receptors in human endometrium during the menstrual cycle. Acta ObstetGynecolScand81: 817-824.

- Bu Z, Yang X, Song L, Kang B, Sun Y (2019) The impact of endometrial thickness change after progesterone administration on pregnancy outcome in patients transferred with single frozen-thawed blastocyst. ReprodBiol Endocrinol17(1): 99.

- Usadi R, Groll J, Lessey B, Lininger R, Zaino R, Fritz M, Young S (2008) Endometrial Development and Function in Experimentally Induced Luteal Phase Deficiency. J Clin Endocrinol &Metab93: 40584064.

- Yoo J, Kim T, Fazleabas A, Palomino W, Ahn S, Tayade C, Schammel D, Young S, Jeong J, Lessey B (2017) KRASActivation and over-expression of SIRT1/BCL6 Contributes to the Pathogenesis of Endometriosis and Progesterone Resistance. Sci Rep28;7(1): 6765.

- Hu M, Li J, Zhang Y, Li X, Billig,H, et al (2018) Endometrial progesterone receptor isoforms in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Am J Transl Res10: 2696–2705.

- Patel B, Rudnicki M, Yu J, Shu Y, Taylor R. (2017) Progesterone resistance in endometriosis: origins, consequences and interventions. Acta Obstetricia et GynecologicaScandinavica96:623-632.

- Pandit R, Biliangady R, Tudu N, Kinila P, Maheswari U, Gopal I, Swamy A (2019) Is it time to move toward freeze-all strategy? – A retrospective study comparing live birth rates between fresh and first frozen blastocyst transfer. J hum Reprod Sci12: 321-326.

- Yang J , Zhang X , Ding X , et al. (2021) Cumulative live birth rates between GnRH-agonist long and GnRH-antagonist protocol in one ART cycle when all embryos transferred: real-word data of 18,853 women from China. Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology, 19(1).

- Dar S, Lazer T, Shah PS, Librach CL.( 2014) Neonatal outcomes among singleton births after blastocyst versus cleavage stage embryo transfer: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Hum Reprod Update20: 439–448.

- Cox GF, Burger J, Lip V, Mau UA, Sperling K, Wu BL, et al. (2002) Intracytoplasmic sperm injection may increase the risk of imprinting defects. Am J Hum Genet71: 162–164.

- DeBaun MR, Niemitz L, Feinberg AP. (2003) Association of in vitro fertilization with Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome and epigenetic alterations of LIT1 and H19. Am J Hum Genet 72: 156–160.

- Gicquel C, Gaston V, Mandelbaum J, Siffroi JP, Flahault A, Le Bouc YL. (2003) In vitro fertilization may increase the risk of Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome related to the abnormal imprinting of the KCNQ10T gene. Am J Hum Genet72:1338–1341.

- Maher ER, Brueton LA, Bowdin SC, Luharia A, Cooper W, Cole TR, et al. (2003) Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome and assisted reproductive technology (ART). J Med Genet40: 62–64.

- Moll AC, Imhof SM, Cruysberg JR, Schouten-van Meeteren AY, Boers M, van Leeuwen FE. (2003) Incidence of retinoblastoma in children born after in vitro fertilisation. Lancet36: 309–310.

Impact Factor: * 3.2

Impact Factor: * 3.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.63%

Acceptance Rate: 76.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks