A Digital Dashboard for Visual Representation of Child Health Information: Results of A Mixed Methods Study on Usability and Feasibility of A New CHILD-Profile

Miriam Weijers1*, Jonne Van der Zwet2, Nicolle P.G. Boumans2, Frans J.M. Feron3, Caroline H.G. Bastiaenen4

1MSc,MD. Department of Child Health Care, Municipal Health Services, Southern Limburg, Heerlen, The Netherlands & Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Care and Public Health Research Institute, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

2PhD, MD. Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

3PhD, MD. Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Care and Public Health Research Institute, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

4PhD. Department of Epidemiology, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Care and Public Health Research Institute, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands

*Corresponding Author: Miriam Weijers, MSc, MD. Department of Child Health Care, Municipal Health Services, Southern Limburg, Heerlen, the Netherlands & Department of Social Medicine, Faculty of Health, Medicine and Life Sciences, Care and Public Health Research Institute, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Received: 15 February 2023; Accepted: 22 February 2023; Published: 09 March 2023

Article Information

Citation: Miriam Weijers, Jonne Van der Zwet, Nicolle P.G. Boumans, Frans J.M. Feron, Caroline H.G. Bastiaenen. A Rare Case of Childhood Hepatitis A Infection with Bilateral Pleural Effusion Acalculous Cholecystitis and Massive Ascites. Journal of Pediatrics, Perinatology and Child Health. 7 (2023): 29-44.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: A digital 360°CHILD-profile, developed within Dutch preventive Child Health Care, visualizes and theoretically orders relevant health information in line with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health. This comprehensible dashboard is designed make electronic health data accessible and facilitate transformation towards Personalized Health Care.

Methods: In a pragmatic Mixed Methods study, 360°CHILD-profile’s usability and feasibility was evaluated. The level of use was measured quantitatively, as well as determinants for implementation at the level of the CHILD-profile itself, its users and the organisational context. Qualitative methods were used to gain understanding of quantitative findings and explore CHILD-profile’s potential benefits.

Results: Participating professionals (n=17) discussed personalized CHILDprofiles with parents (n=27). Twelve interviews (parents and professionals) and two focus groups were performed. After integrating quantitative and qualitative data, the overall theme “readiness for implementation” emerged. Participants reacted enthusiastically about discussing the CHILD-profile and appreciated the quick overview on holistic health information. Hindering organisational issues were mentioned, including the non-structured electronic medical dossier.

Conclusions: This study demonstrated the 360°CHILD-profile to be useful and efficient for CHC-practice. Users seem competent in handling and using the CHILD-profile within the CHC-context. Knowledge on how to get ready for implementation was generated.

Keywords

Child Health Services, Personalized Health Care, International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Patient Access to Records, Implementation

Child Health Services articles, Personalized Health Care articles, International Classification of Functioning articles, Disability and Health articles, Patient Access to Records articles, Implementation articles

Article Details

Key messages:

- A new 360°CHILD-profile visualizes theoretically ordered health information in one image.

- The 360°CHILD-profile enables to digitally disclose a manageable résumé of medical records.

- This dashboard is a useful and efficient tool for CHC-practice.

- The quick overview on holistic health data accurately represents a child’s health situation. This Mixed Methods study generated theory on how to target the implementation strategy.

Trial registration: NTR 6909; https://www.trialregister.nl/trial/6731

Introduction

The Dutch preventive Child Health Care (CHC) pro-actively monitors children’s health from birth until the age of 18. Since the CHC focuses on protecting and promoting children’s health, it is a potentially suitable platform for adopting Personalized Health Care (PHC) [1,2]. PHC is said to be indispensable for addressing increasing burden and costs of chronic diseases [3,4]. PHC includes personalized prevention, prediction and active participation of care-receivers [5]. An essential condition for fully integrating these PHC-concepts is access to high-quality information on children’s health. Although CHC collects and registers longitudinal, holistic health data in an electronic medical dossier (EMD), access to representable data is currently hindered, due to EMD’s non-theoretical structure and lack of overview [6-10].

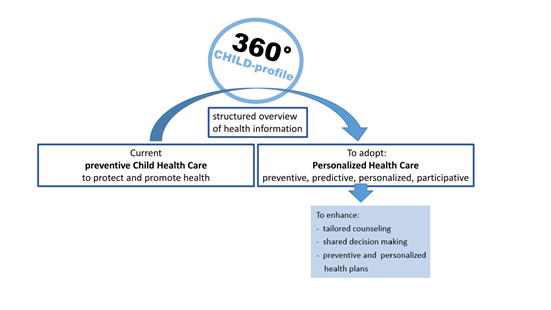

Therefore, a dashboard named 360° CHILD-profile was developed to visualize all relevant health information retrieved from the EMD, in one image. In this dashboard, data are theoretically ordered in line with the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Children and Youth version (ICF-CY). It displays the biopsychosocial concept of health in a cohesion of different health domains (body structures/functions, activities, participation, environmental and personal factors) [11]. The design of this dashboard offers a comprehensible overview on multidimensional and complex health data (Weijers et al., 2021a) and provides professionals and parents with direct access to a manageable résumé of a child’s medical record. The 360° CHILD-profile aims to facilitate clinical reasoning processes in line with PHC and enhance tailored counselling and shared decision making toward preventive, personalized health plans (see Figure 1).

During the iterative design process, international standards for representing health information were applied. Professionals and parents were actively involved to increase usability and likelihood of reaching CHILD-profile’s goals [12,6]. A pilot study showed positive results on validity and reliability of the CHILD-profile [13]. Next, several tests revealed the CHILD-profile was comprehensible for communication between professionals and parents [12]. However, it was not known yet whether the CHILD-profile might be useful within real life CHC-practice, nor whether implementation and evaluation of its effectiveness would be feasible.

Therefore, while introducing this CHILD-profile within practice, a pragmatic Mixed Methods feasibility research project [14,15] was carried out, which comprised of two studies. The first study entailed an evaluation of CHILD-profile’s usability and feasibility. The second study concerned a parallel evaluation of executing a randomized trial within this setting, of which the results will be reported in a separate paper. The protocol of the entire research project is described in detail elsewhere [16].

The present paper presents the evaluation of CHILD-profile’s usability and feasibility. In this evaluation, usability was defined as “usable for presenting children’s health situations” and “users expect it to be useful”. Feasibility was defined as “potential attainability for implementation within CHC” [17].

This study was performed in line with the theoretical framework of Fleuren et al. [18]. This framework focuses on how to systematically introduce and evaluate an innovation in a preventive health care setting. At the same time, it brings to surface the broad variety of determinants that potentially influence the implementation process. These determinants relate to the level of the CHILD-profile itself, its users, and the organisational and socio-political context.

To evaluate the CHILD-profile’s usability and feasibility, the following research questions were formulated:

- What is the attainability of implementing the CHILD-profile, regarded as its level of use and related key determinants?

- How do parents and professionals experience the use of the CHILD-profile and what are their perspectives on its usefulness and implementation within CHC?

- What is the view of policy-makers on the CHILD-profile’s usefulness and future implementation within CHC?

Methods

Study design: This study comprises two parts with equal priority: a quantitative part, with a structured questionnaire in line with the framework of Fleuren (research questions 1), followed by a qualitative part, with semi-structured interviews and focus group meetings (research questions 2 and 3) [14-16, 19].

Quantitative and qualitative data were integrated by utilising quantitative data to select participants for the interviews, refine topic lists and by comparing overarching themes for both types of data-sources.

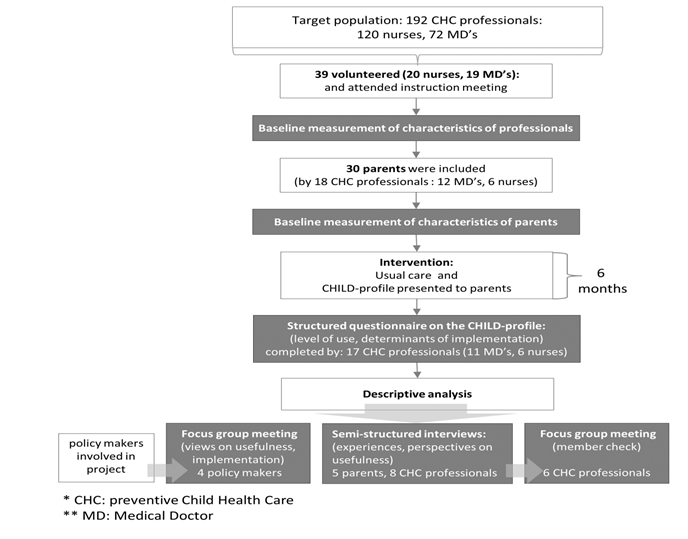

Study population and recruitment: All nurses (n=120) and medical doctors (n=72) from the CHC-departments in the South of the Netherlands were invited to participate. Volunteering professionals attended an instruction meeting and were expected to recruit one or two parents who visit their consultation hours. The only exclusion criterion for parents was a substantial language barrier that hindered the profile’s readability.

For the interviews, a sub-sample of all included CHC-professionals and parents was purposefully selected to obtain a heterogeneous subgroup [20] with contrasting characteristics (parental stress, educational level, native country, their child’s age and functioning and professionals’ discipline and experience) and contrasting quantitative outcomes (parent’s opinion on CHC, professional’s satisfaction regarding the EMD). Policymakers (two managers of the CHC-organisation, a representative of local municipalities and a member of the national CHC’s knowledge centre) were invited for a separate focus group meeting. In the final phase, all interviewed CHC-professionals were invited for a member check focus group meeting. All participants gave written informed consent. Figure 2 displays recruitment and flow of all participants.

Intervention period

The CHC-professionals provided care as usual and presented and discussed a personalized CHILD-profile with all parents during a CHC-consultation. Randomly [12], a personalized CHILD-profile was offered for 50% of the parents shortly after recruitment and baseline measurement. This CHILD-profile remained available during the six-month intervention period via an online portal (for parents) and the EMD (for CHC-professionals). The other half of the parents received a personalized CHILD-profile during a CHC-consultation at the end of the study, after completing the RCT’s intervention period and follow-up measurements of the parallel executed study [12].

Measurements

Measurement of characteristics at baseline: Baseline measurements assessed professionals’ characteristics, and those of parents and children for whom parents participated (see Table 1 and 2). The protocol article describes the baseline measurements in more detail [12].

Quantitative measurements: To address research question 1, professionals who succeeded in including at least one parent and thus experienced working with a CHILD-profile, received a questionnaire based on the Measurement Instrument for Determinants of Innovations (MIDI) after the intervention phase [18].

To measure CHILD-profile’s level of use, the MIDI questionnaire included questions on if (yes/no) and how profoundly (4-point scale) CHC-professionals discussed the personalized CHILD-profiles with parents and/or spontaneously used it for other CHC-tasks (preparing visits, assessing child functioning, exploring parent’s perspective, collaborating with colleagues and other caregivers). Additionally, professionals indicated their opinion (on a 5-point scale) on determinants that may affect the level of use (and thus implementation) at three levels: the level of the innovation (procedural clarity, completeness, relevance, correctness, compatibility with CHC); the users (self-efficacy, personal benefits (i.e. quickly gaining overview and added value for consultations, clinical reasoning, communication, empowerment and participation of parents), personal drawbacks (i.e. cost of extra time, if it is confronting)); the organisation (formal ratification and facilitation (i.e. time, staff and level of turbulence)) [18].

Qualitative measurements: To answer research questions 2 and 3, semi-structured interviews were performed by MW, as well as focus group meetings (guided by MW, CB and FF).

Topic lists for semi-structured interviews with CHC-professionals and parents included questions regarding their perspectives on and experiences with CHC in relation to the development and upbringing of children, and their experience with the CHILD-profile (including potential benefits/drawbacks, requirements for implementation). Topic lists for individual interviews were slightly customized, considering already collected quantitative outcomes (individual and preliminary group findings) [21].

During the member check focus group meeting, the most relevant findings and preliminary interpretations were presented and professionals were asked whether these findings and interpretations reflected their experiences, and to further elaborate on and/or explain the findings [22,23].

The topic list for the separate focus group meeting with policy-makers, included questions about their perspectives on the CHILD-profile (relevance, strengths, weaknesses, its implementation) in relation with their vision on future care for children.

All interviews and focus group meetings, were audio recorded (after explicit informed consent) and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Baseline characteristics

Descriptive analyses were performed (means, standard deviations, frequencies and percentages) on data of parents and professionals. Characteristics of CHC-professionals are presented for the total group of initial volunteers and sub-group that actually recruited parents and discussed CHILD-profiles. Participant characteristics of the qualitative sub-sample are presented separately.

Main quantitative analyses

For quantitative measurement of CHILD-profile’s level of use and determinants of implementation by professionals, descriptive analyses were performed.

Qualitative analyses

Qualitative analyses were performed by a team of multidisciplinary researchers (MW, FF, CB, JZ, NB) with experience in quantitative and/or qualitative research. Three researchers have experience as a Medical Doctor in CHC-practice (MW, FF, JZ).

Transcripts were analysed using the software program NVivo 12 Pro [24].

First, data retrieved from each interview/focus group were explored and analysed by the first author (MW) and one other researcher, independently. Then, findings were discussed to reach consensus. After each round of analysing 3-5 interviews, findings were discussed in the whole team to reflect on data and analyses, broaden the analytical scope, and decide on further sampling and adapting topic lists.

During several phases, constant comparative analysis was performed and MW wrote reflective memos. The first inductive phase, included open coding of relevant text fragments. After analysing three interviews, codes were arranged, renamed and/or related to each other to identify and pragmatically structure categories (axial coding). In the last, more abductive phase, the team related data to quantitative findings and knowledge from literature to identify core concepts and themes (selective coding) [25, 26]. Codes and categories then were restructured in line with the conceptual framework that seemed most appropriate within the given context; the framework of Fleuren [18, 21]. After the team concluded no new, relevant elements were generated anymore, interpretations were described and validated during the “member check” focus group meeting [25, 26].

Results

Recruitment and baseline characteristics of all participants

Of the CHC-professionals, 46% included at least one parent and discussed a personalized CHILD-profile. Almost all invited CHC-professionals completed the MIDI-questionnaire. In total, 30 parents were included. Due to loss to follow up, 27 personalized CHILD-profiles were discussed with parents (see Figure 2).

Baseline characteristics of participating CHC-professionals were heterogeneous regarding discipline, target group (age of children), educational level and experience (see Table 1). Most professionals were rather satisfied with the EMD, rather known with the CHILD-profile, had positive expectations regarding the CHILD-profile’s usability but had little to no prior experience with it.

Participating parents were rather heterogeneous regarding educational level, experienced problems, parental stress and level of their child’s functioning (moderate to high functioning, as indicated by CHC-professionals) (Table 1).

|

Characteristics CHC*-professionals |

Total group of CHC-professionals (n=38) Number (%) |

CHC-professionals who successfully included parents (n=18) Number (%) |

|

Discipline: nurse medical doctor |

20 (53) 18 (47) |

6 (33) 12 (67) |

|

Target group: children age 0-4y. children age 4-18y. |

18 (47) 20 (53) |

10 (56) 8 (44) |

|

Educational level: no specific CHC-education introduction course CHC specialist CHC |

18 (47) 4 (11) 16 (42) |

6 (33) 3 (17) 9 (50) |

|

Experience within CHC*: < 5 years 5-10 years > 10 years |

10 (26) 0 28 (74) |

4 (22) 0 14 (78) |

|

Satisfaction with current EMD satisfied rather satisfied rather unsatisfied unsatisfied |

3 (8) 25 (66) 9 (24) 1 (3) |

0 13 (72) 5 (28) 0 |

|

Known with 360°CHILD-profile very known rather known little known not known |

4 (11) 26 (68) 7 (18) 1 (3) |

2 (11) 13 (72) 2 (11) 1 (6) |

|

Experience with 360°CHILD-profile much rather much little no experience |

0 3 (8) 11 (29) 24 (63) |

0 1 (6) 9 (50) 8 (44) |

|

Opinion about possibility to positive use 360°CHILD-profile rather positive rather negative negative |

23 (61) 14 (37) 1 (3) 0 |

12 (67) 6 (33) 0 0 |

|

Number of parents recruited/included: one two-three > four |

Recruited 13 (34) 8 (21) 3 (8) |

Included 11 (61) 5 (28) 2 (11) |

Table 1: Baseline characteristics of participants.

Eight out of ten invited CHC-professionals, participated in an interview. Five parents were invited for an interview and participated in it. See Table 2 for characteristics of parents and professionals.

|

Parents |

Child’s age group |

Child functioning (STEP a) 6-30 (high-low) |

Parental stress (NOSIK b) |

Educational Level |

Birth country |

Score for CHC 0-10 |

|

1 |

4-18 |

11 |

< average |

intermediate |

non-Dutch |

8 |

|

2 |

0-4 |

21 |

< average |

high |

Dutch |

10 |

|

3 |

0-4 |

19 |

> average |

intermediate |

Dutch |

8 |

|

4 |

0-4 |

6 |

average |

high |

Dutch |

8 |

|

5 |

4-18 |

- |

- |

intermediate |

Dutch |

- |

|

Professionals |

Target age group |

Discipline |

Experience in CHC |

Satisfaction with EMD |

||

|

1 |

0-4 |

medical doctor |

>15y |

rather satisfied |

||

|

2 * |

4-18 |

nurse |

0-5y |

rather unsatisfied |

||

|

3 * |

0-4 |

nurse |

>15y |

rather satisfied |

||

|

4 * |

4-18 |

medical doctor |

>15 |

satisfied |

||

|

5 * |

4-18 |

medical doctor |

0-5 y |

rather satisfied |

||

|

6 * |

0-4 |

medical doctor |

>15y |

satisfied |

||

|

7 * |

0-4 |

nurse |

5-10y |

- |

||

|

8 |

4-18 |

medical doctor |

>15 y |

satisfied |

||

a STEP functioning score: Dutch standardized professional's rating of child's functioning on a (reversed) continuous scale (Van Yperen et al., 2010)

b NOSIK: Dutch short version of parenting Stress Index; parents’ perspective on an ordinal scale (Brock at al., 1992)

*also participated in member check focus group meeting.

Table 2: Characteristics of parents and CHC professionals, who participated in the semi-structured interview.

All interviewed CHC professionals were invited for the member check focus group meeting, of whom six participated. During a separate focus group meeting, four policy-makers participated: two managers of the CHC-organisation, two advisors (one of the regional municipality and one of the CHC’s national knowledge centre).

Level of use of the 360° CHILD-profile: An overview of results regarding the level of use is presented in table 3. In total, 27 of the 30 CHILD-profiles were discussed by 14 professionals. Less than half of the professionals discussed the profiles profoundly. The majority used them to prepare for CHC-consultations/visits, show promoting factors for children’s health and/or assess children’s functioning. The profile was less often and/or profoundly used to gain insight in parents’ perspectives, empower parents, or collaborate with colleagues and other caregivers.

|

Reported use of the CHILD-profile. Questions: |

Yes Nr. (%) (N=17) |

Extensively * Nr./N used (%) |

Reasons why; Reactions on open questions: |

|

|

Why did you use and/or extensively use it? |

Why did you not use or not extensively use it? |

|||

|

Did you present the CHILD-profile to parents? |

14 (82%) |

6/14 (43%) |

- “In context of the study”. - “To check if data were correct”. - “There was time and parent was interested”. |

- “Limited time”. - “Other goals of the visit”. - “My colleague did it”. |

|

If presented, did you also use the CHILD-profile to: |

(applicable for n=14) |

Why did you not use or not extensively use it for other purposes: |

||

|

Show what goes well? |

11 (79%) |

2/9 (22%) (2 missings) |

- “This was already addressed in other visits”. - “The profile is a résumé, so it offers overall guidance. Beyond that, we addressed other goals of the visit”. - “There were no particulars we had to extensively dive into”. - “The profile was not optimally filled due to missing data in the EMD”. |

|

|

Assess child’s functioning? |

9 (64%) |

5/9 (56%) |

||

|

Prepare a visit? |

9 (60%) |

5/9 (56%) |

||

|

Explore parent’s perspective? |

7 (50%) |

3/7 (43%) |

||

|

Collaborate with caregivers? |

4 (29%) |

1/4 (25%) |

||

|

Collaborate with school? |

3 (21%) |

0 /3 (0%) |

||

|

Collaborate with colleague’s? |

1 (7%) |

0 /1 (0%) |

||

Table 3: Level of use of the 360°CHILD-profile, including professionals’ short explanations for the reported use.

Readiness for implementation

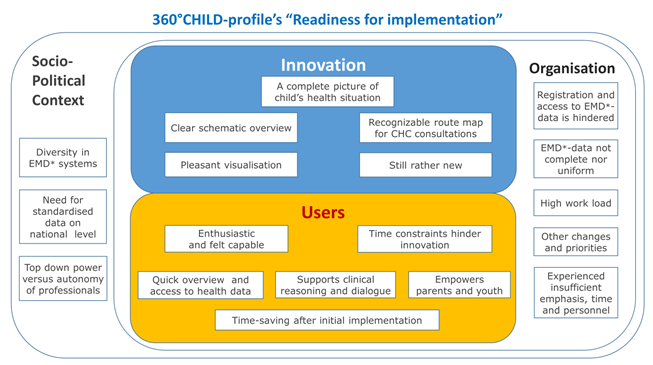

With regard to key determinants of the level of use and the context of research questions 2 and 3, integration of quantitative and qualitative data during qualitative analyses led to a repeatedly emerging theme: “readiness for implementation” (Figure 3). This theme provided insight in the current situation, future possibilities, and needs for further implementation regarding the CHILD-profile itself, the people using it, the organisation and the socio-political context.

Therefore, Fleuren’s theoretical framework (Fleuren et al., 2014a, 2014b) was used to structure findings regarding the readiness for implementation. Table 4 provides an integrative summary of qualitative and quantitative findings, including participants’ quotes and original Fleuren’s determinants. Figure 3 provides an overview of key findings based on both types of data.

* EMD: Electronic Medical Dossier

Determinants at the level of the innovation:

Quantitative results showed that most professionals stated that the CHILD-profile offers sufficient and relevant information, fits CHC’s working methods and clients, is based on adequate knowledge, and it was clear how to present it.

Integrating quantitative and qualitative data led to the following subcategories with respect to the CHILD-profile itself (see table 4 for underlying quotes):

- A summative recap of a child’s health situation.

Parents appreciated that the CHILD-profile displays all essential information in one image. Professionals and policy-makers believe it offers a model to generate a complete picture of a child’s health situation. However, professionals mentioned the need for a direct link to the EMD for viewing more detailed information as the CHILD-profile entails a compact, overall summary. Moreover, it appeared that not all profiles were complete (some data fields were empty) due to missing data in the EMD.

- Schematic overview and neutral visualisation.

Both parents and professionals stated the neutral visualisation of data was pleasant and the overview with ordering in subcategories was clear, as well as the provided instructions. The CHILD-profile made the health information manageable and easy to find.

- Route map for CHC-consultations

Professionals mentioned that discussing the profile with parents fitted their regular CHC-visits and their longitudinal monitoring of development and health. The profile offers a recognizable route map for their dialogues with parents and adolescents, and displays for which topics and questions the CHC can be consulted.

- Experience

Professionals and parents felt they did not yet gain full insight in all potential benefits as this was their first, brief real-life experience with the profile. They expected that after full implementation and insight in benefits, an evaluation would generate even more positive results on usability. Professionals were eager to become more familiar with the profile and would appreciate possibilities to exercise in dialogue with colleagues.

Determinants at the level of the users:

Quantitative data showed that most professionals felt capable to use the CHILD-profile for describing and discussing a child’s health situation. They agreed on the following benefits: it offers a quick overview on relevant health data and supports their medical reasoning. More than half of the professionals indicated that the CHILD-profile supports their consultations and communication with parents. Less than half of the professionals agreed it stimulates empowerment and participation of parents. Half of the professionals indicated it costs extra time. One professional indicated the CHILD-profile offers information which might be rather confronting for parents.

Integrating quantitative and qualitative data, revealed the following qualitative subcategories with respect to the users (see table 4 for underlying quotes):

- Self-Efficacy

CHC-professionals were enthusiastic about their own profession and providing care for children and supporting parents. Parents acknowledged CHC-professionals as driven, competent caregivers who support and reassure concerned parents.

Parents and professionals were enthusiastic and interested in the CHILD-profile. Most professionals felt capable to discuss the profile to parents. A few professionals contacted the researcher before discussing the profile with parents but stated that a short phone call was enough for reconfirmation of instructions.

- Access to health data

Parents said the CHILD-profile showed them what data professionals register in the EMD and enabled them to easily consult background information between visits. Professionals appreciated the quick access to relevant holistic health data and the possibility to provide parents with relevant health information via the online portal. The importance of guaranteeing privacy protection was mentioned by both professionals and parents.

- Clinical reasoning and dialogue.

During visits, parents felt supported by the profile by reminding them about their child’s upbringing and relevant issues and events in the past. Professionals stated that the ordering of data provides insight in the cohesion between different items. It supports the transfer of this insight to parents, and supports sharing visions on how imbalances between protective- and risk factors emerged. The profile could further support consulting colleagues and other caregivers and ease conversations with adolescents by creating a setting in which professional and adolescent share the same screen with information.

Some professionals wondered if it would benefit parents of children without evident developmental and/or health problems, while others emphasized the importance of having insight in every child’s health information, including what goes well.

- Empowerment

Parents and professionals appreciated the display of positive aspects of a child and their family and the possibility to share data with other caregivers. During a consultation with several caregivers, the profile enabled a parent to formulate her family’s needs and to take an active role during shared decision making. Some professionals expected the profile might be confronting for low educated parents who experience severe problems, while others thought the neutral display of both facilitating and hindering factors makes it less confronting.

- Time investment

Most professionals experienced that, due to time constraints, it was hard to find time for their study tasks. At the end of a working day, they felt the urge to choose between tasks regarding actual daily care and the study. The majority tend to prioritize daily care tasks.

Most professionals think that CHILD-profile’s implementation and evaluation will cost some extra time. However, they believed that, after implementation, the quick access to health information will lead to efficiency and the CHILD-profile will become timesaving.

Determinants at the level of the organisation: Quantitative results showed that the majority of CHC-professionals indicated that, apart from this study, more changes within the organisation took place, such as a merger and other innovations. The minority of professionals indicated their management sufficiently facilitated the innovation, stressed the importance of it, and that there was sufficient time and personnel available.

With respect to the organisation, the following subcategories emerged after integrating quantitative and qualitative data (see table 4 for underlying quotes):

- Aspects of work load and emphasize

Professionals, for a long time already, experienced a high workload in completing their daily tasks. During the study period, other organisational changes were prioritized.

Professionals indicated that staff capacity was low and felt there was not enough time for testing this new tool. Professionals said that only the researcher (MW) communicated about the project. They were hardly informed by their managers about the project and the importance of the innovation.

- Registration and access to EMD-data

All professionals mentioned that registration and retrieval of data from the EMD is time consuming due to a lack of structure and overview of registered data. According to them, the CHILD-profile provides better overview and support for executing their CHC-tasks.

Professionals stated that currently, EMD-data are registered inconsistently and not always complete. The CHILD-profile can create awareness about which relevant information is missing within EMD-registries and could help to achieve more complete and structured registries.

Determinants on the level of the socio-political context: Determinants at the level of the socio-political context were not measured quantitatively. During the focus group meetings and some interviews, the national CHC-context was discussed. Qualitative analysis revealed the following subcategories (Table 4 includes underlying quotes):

- EMD systems and standardized data on national level

Policy-makers regard the presentation of health information on a population level (regionally and nationally) as an important CHC-task. They mentioned serious constraints in current CHC-data registries, such as the diversity in EMD systems and a common lack of theoretically structuring of data. Policy-makers referred to the CHILD-profile as “a golden egg”. They stated that it is built on a solid vision and scientific background, and has great potential: a multifunctional tool for reaching standardized registration, stimulating ICF-thinking, optimising prevention and prediction, and empowering parents.

- Top down power versus professional autonomy

To solve problems concerning the electronic health-data registries and to enable the delivery of data on a population level, policy-makers stated the need for more top-down policy. At the same time, they realized that a certain level of autonomy is essential for health care professionals.

Policymakers listed several steps needed for preparing national implementation: to secure intellectual property, to collaborate with national stakeholders (i.e. knowledge centre CHC, association for Public Health), to build a sound marketing strategy, and to describe how the CHILD-profile could support other developments in the health domain in the Netherlands, such as Positive Health.

|

Key findings (qualitative subcategories) |

Qualitative quotes parents, professionals, policy-makers |

Quantitative results professionals * |

Original Fleuren determinants |

||

|

Determinants at the level of the innovation: |

|||||

|

A complete picture of child’s health situation (A summative recap of child’s health situation) |

Parents: Nr.1: “All information from birth on is documented on the profile.” Nr.4: "You see all essentials at a glance in a comprehensible way. You do not need to flip through many pages." Nr.5: “It would be easy if you could link back to the information behind it, like the growth chart in the EMD.” Professionals: Nr.2: “It provides me with a complete picture.” Nr.6: “It includes all elements that we, as CHC professionals, take into account. A synthesis of all EMD domains." Nr.6: “As some profiles were incomplete, I wondered if I registered all data well in the EMD.” Nr.5: "The profile offers a résumé, shows a global picture. For detailed information you still need a link to the EMD” |

It contains sufficient relevant information. - Agree: 15 (88%) - Neutral: 2 (12%) - Disagree 0 |

Completeness and Relevance |

||

|

It is based on adequate knowledge. - Agree: 11 (65%) - Neutral: 6 (35%) - Disagree 0 |

Correctness |

||||

|

Clear schematic overview and pleasant visualisation (Schematic overview and neutral visualisation) |

Parents: Nr.2: “It is schematic with categories, which makes it very clear how and where to find information.” Nr.5: "I think it has a very pleasant, calm look. Professionals: Nr.4: “It offers a clear overview and it would be beneficial if you can go, by clicking on a domain within the overview, to more detailed information about that domain.” Nr.6: "I found it very pleasant to present the profile and the parents thought so too.” Nr.7: "It looks clear and joyful. The EMD contains much more letters and needs much more reading, doesn’t it?" Nr.8: “The instructions given during the instruction meeting were loud and clear as well as the written information.” |

It is clear how to present it. - Agree: 14 (82%) - Neutral: 3 (18%) - Disagree 0 |

Procedural clarity |

||

|

Recognizable route map for CHC consultations (Route map for CHC- consultations) |

Parents: Nr.4: “I think it would be fit for all parents, from all different layers of the population and would be comprehensible and clear for all levels of intelligence.” Professionals: Nr.8: “It fits the CHC very well, it shows what we take into account when checking the balance between protecting and risk factors.” Nr.5: “The profile supports my usual approach and offers a route map for my consultations with parents.” Nr.6: “It shows for what questions/topic parents can consult the CHC.“ Nr.7: “I think I could start with the CHILD-profile right away in regions where not too many parents live who experience a lot of problems, have low educational level or with a language barrier.” |

It fits CHC’s: -Working method. - Agree:13 (77%) - Neutral: 4 (23%) - Disagree 0 -Clients. - Agree: 12 (71%) - Neutral: 5 (29%) - Disagree 0 |

Compatibility |

||

|

Still rather new (Experience) |

Parents: Nr.2: “As it is new, it is important that parents know what the added value is. Then I think they will be up for it.” Professionals: Nr.1: “It is still new for me. That’s why I found it hard to explain what the benefits for parents are.” Nr.3: “I filled in the questionnaire while having only litle experience with the CHILD-profile. If we would work with it more extensively, I think the outcome of the questionnaires would be even more positive.” Nr.2: “I find it hard to do something new immediately in the face of parents. I would firstly like to practice with colleagues to get more acquainted with it.” |

||||

|

Determinants at the level of the users: |

|||||

|

Enthusiastic and felt capable (Self-Efficacy) |

Parents: Nr.3: “I found it very interesting so I would make it very big, this project, because I think you can do a lot with it.” Nr.2: “The CHC-professionals are friendly and competent and supports parents very well.” Professionals: Nr.4: “CHC-professionals know what domains are important and we are used to try to gain an overall picture of the child. So, I think we are all capable to work with this clear and insightful overview.” Nr.8: “I always work with mind maps to support my overall view on children’s health. As the CHILD-profile perfectly fits my way of thinking, it did not feel new working with it.” Nr.5: “It works itself out. Well the first time, I did call the researcher to ask her how to discuss the profile with parents but it became clear that it did not really differ from how I usually approach consultations.” |

Felt capable to: -Present the profile - Agree:13 (76%) - Neutral: 3 (18%) - Disagree: 0 (1 missing) -Assess functioning - Agree: 12 (71%) - Neutral:4 (23%) - Disagree 0 (1 missing) |

Self-efficacy |

||

|

Quick overview and access to health data (Access to health data) |

Parents: Nr.4: "During consultations, many questions are asked and information is registered in the EMD and we look at the graphic of growth together. With the profile, the professional can show me on one digital image all EMD-data.” Nr.1: “The availability on the online CHC portal, offers me the opportunity to consult information between CHC visits and to provide access to other persons for whom the information is important.” Professionals: Nr.3: “Added value, in comparison with EMD, is that you can quickly show summary of information to parents and colleagues.” Nr.6: “It would be very nice to make this overview accessible for parents via the online portal.” |

It provides quick overview - Agree: 5 (88%) - Neutral: 1(6%) - Disagree 1 (6%) |

Personal benefits and/or drawbacks |

||

|

Supports clinical reasoning and dialogue (Clinical reasoning and dialogue) |

Parents: Nr.2: "It is like a medicine list, visible for anyone. If you must go to the emergency room and you don’t remember it all, you can easily find back all information." Nr.4: “It is nice to be able to look back at how I was doing then and see how I am doing now.” Professionals: Nr.4: “The CHILD-profile offers the opportunity to also show adolescents the whole picture; how different health domains are connected and how imbalances did occur.” Nr. 5: “It is nice and clear for health literacy and consultations with colleagues and other care givers” Nr.2: “I do not know if it has added value if all goes well.” Nr.6: “I think it would be a good idea to use the profile for all children as it is nice and beneficial for all parents to see what goes well. And that the child is our central interest and that the features of the child are connected with the environment in which the child grows up.” |

It supports: * Your thought processes. - Agree: 14 (84%) - Neutral: 3 (18%) - Disagree 0 * CHC consultations. - Agree: 10 (59%) - Neutral: 7 (41%) - Disagree 0 * Communication. - Agree: 10 (59%) - Neutral: 7 (41%) - Disagree 0 |

|||

|

Empowers parents and youth (Empowerment) |

Parents: Nr. 4: "The compact information makes me analyse much better what is going on and formulate my question.” Nr.1: “It will support me during the intake consultation I will have with a caregiver. As all information is available on the profile, so that I do not forget to mention things.” Professionals: Nr.5: “I used the profile during a care match consultation with other caregivers who did not know anything about the child yet. The mother used the profile to guide her in describing her child and her family, what the history looked like and what problems they encounter.” Nr.2: “Reading the information on the profile might be problematic for parents who do not understand Dutch and confronting for parents with low education who experience a lot of problems”. Nr.3: “As it provides an overview, it makes discussing barriers less confronting then in the current situation because the profile also contains information about what goes well”. |

It stimulates: -An integral approach - Agree: 11 (71%) - Neutral: 4 (23%) - Disagree 1 (6%) (1 missing) -To empower parents - Agree: 8 (47%) - Neutral: 8(47%) - Disagree 1 (6%) -Parents’ participation - Agree: 7 (41%) - Neutral: 0 (59%) - Disagree 0 (0%) |

|||

|

Time constraints hinder innovation (Time investment) |

Professionals: Nr.7: “I love my job and do it with much passion. However, it is very busy and at the end of the day I have to prioritize and then I choose to finish urgent tasks related to clients.” |

||||

|

Time-saving after initial implementation (Time investment) |

Parents: Nr.1: "The profile provides me quickly with a summary of my child’s health situation. That is nice and could save time.” Nr.2: “If, during puberty, my child will again experience problems, with one click on the computer, you get information about what happened in the past, who performed earlier psychological examinations and what the outcome was.” Professionals: Nr.3: “After becoming familiar with the profile, it can be time-saving as you can start with showing what has been discussed the last time and how is it going now?” Nr.5: “The profile enables me to form a picture of the family and the child before I see a them for the first time. That will save me much time, as I now have to open a lot of tabs within the EMD to prepare for a visit.” Nr.2: After a while it will make you finish work faster, but during implementation it will costs extra time while we already experience high work load. So, you might encounter some resistance during the first stages.” |

It costs extra time - Agree: 9 (53%) - Neutral: 5 (29%) -Disagree 2 (12%) It is confronting for parents - Agree: 1 (6%) - Neutral:11(65%) - Disagree 5(29%) |

|||

|

Determinants at the level of the organization: |

|||||

|

Experienced insufficient emphasis, time and personnel (Aspects of work load and emphasize) |

Professionals: Nr.4: “All professionals in our team know about the project and expect for it to get implemented but it takes very long” Nr.5: “The only communication about the project comes from the head researcher. Besides that, I hear very little about the project and it does not feel like we are all really going for it.” Nr.4: “I don’t remember how I exactly answered these questions within the questionnaire, it was quite a while ago. But I am not surprized about the overall low scores on ratification and facilitation by the management.” |

Management does: -Stress importance: - Agree (23%) -Facilitate sufficiently - Agree (23%) |

Formal ratification by management |

||

|

There is sufficient: -Personnel - Agree (23%) -Time available - Agree (29%) |

Staff capacity |

||||

|

High workload and other changes and priorities (Aspects of work load and emphasis) |

Parents: Nr.3: “I don’t remember which questionnaire was about this project as I also received another one concerning the new online portal for parents.” Professionals: Nr.5: The workload is very high due to insufficient personnel; it never stops. I like the fact that my job is diverse but I struggle with how to prioritize.” Nr.8: “My agenda was already overloaded due to the high demand for care within area I work in.” Nr.4: “It was a tumultuous time, with the fusion of different CHC-organisations.” Nr.6: “I still discovering what information to provide to parents on the recently introduced online portal for parents.” |

Time available |

|||

|

Other developments took place in organisation - Agree (71%) |

Turbulence within organisation |

||||

|

Registration and access to EMD-data is hindered (Registration and access to EMD-data) |

Parents: Nr.4: “I think the profile has added value for the EMD as information will be better stored." Professionals: Nr.5: ”I hear many colleagues complain about the current EMD. How slow the system works, about the multiple spots where you can register information. And, searching for information in the current EMD is terrible, very time consuming” Nr.2: “I miss structure in the way we register data in the EMD, there are many differences in data registration by professionals. We need to better structure what data we register and where.” Nr.4: “I think the EMD is very unclear and much to extensive and it feels like I have to register data on hundred different places within the EMD.” |

||||

|

EMD-data not complete, nor uniform (Registration and access to EMD-data) |

Professionals: Nr.5: “Not all professionals do consistently fill all data fields. Especially if a child does not experience problems concerning a certain domain, these fields are often empty. We need to create more unity and I think the CHILD-profile can help to standardize data” Nr.2: “Everyone should register information about a certain topic in the same field, otherwise it cannot be shown in the CHILD-profile.” |

||||

|

Determinants at the level of the socio-political context |

|||||

|

Diversity in EMD systems

(EMD systems and standardized data on national level) |

“In the Netherlands, several different EMD’s are in use even when several CHC organisations use the same EMD, every CHC organisation has employed the EMD software differently so we will not be able to generate comparable data. As the Dutch CHC knowledge centre (NCJ) we decide that we want to do something about it.” |

Legislation |

|||

|

Need for standardized data on national level (EMD systems and standardized data on national level) |

NCJ: “It shows the complete picture of a child’s health and intuitively guides professionals to take all domains of the biopsychosocial model of health into consideration as it shows if all components are covered.” Manager: “There is a need for more standardized data. On a national level, a measure is in preparation for the collection of data on a population level.” NCJ: “The current BDS Basic data set to be collected by CHC includes more then 1000 items while this innovation has prioritized about 100 items to display a child’s health situation. That is very interesting and national implementation is important.” Manager: To gain reliable data for policy making, it is better to register a limited number of data well then to register a high number of data while this is not doable and leads to incomplete datasets. Therefore, it is important to present this project on national (governmental) level (GGD GHOR NL/Actiz, Managers CHC, VWS). |

||||

|

Top down power versus autonomy of professionals (Top down power versus professional autonomy) |

Manager: “The need for standardized data require a more top down approach while keeping the balance and leave room for enough autonomy for professionals “It asks for a change in the way professionals think, that is the biggest challenge.” Professionals: Nr.8: “It must be clear for all professionals in what EMD-fields to register the data to get them displayed in the profile.” Nr.6: “If professionals realize their responsibility for providing relevant data for the profile will stimulate better registration.” |

||||

* Percentage of CHC-professionals who agree (indicated they did agree or totally agree), were neutral (indicated they did not agree nor disagree) or disagree (indicated they did disagree or totally disagree). (Total answer options were: totally agree, agree, neutral, disagree, totally disagree.)

Table 4: Integrative summary of the mixed methods findings: qualitative findings, participants’ quotes, quantitative results of the MIDI questionnaire and the original Fleuren’s categories.

Discussion

Study findings demonstrated the CHILD-profile is a useful tool for CHC-practice and promising regarding efficiency. The level of use during the study was satisfactorily, considering this study entailed a first and short introduction of the CHILD-profile within real life practice.

Integrating quantitative and qualitative findings yielded broad insight in the “readiness for implementation”, which appeared to be strongly related to determinants at each of the four levels, described by Fleuren [18].

The CHILD-profile itself, as well as the potential users, seem to be ready for implementation. CHC-professionals and parents received the CHILD-profile very favourably and appeared very well capable in handling and using the CHILD-profile within the CHC-context.

Quantitative and qualitative data supported CHILD-profile’s compatibility to CHC-practice and relevance. Qualitative research provided deeper understanding of its usefulness. Professionals and parents particularly appreciated the schematic and holistic overview on CHC-data as, compared to the EMD, it represents a child’s health situation more accurately and provides quicker access to relevant health data. A potential hindering factor might be that on forehand, one professional thought the overview of data might be confrontational for low educated parents who experience severe problems. However, this individual assumption was in contrast with the actual pleasant and empowering experiences of parents and professionals.

At the level of the organisation, substantial barriers were revealed with regard to the CHILD-profile’s readiness for implementation. The high workload and low staff capacity seem to hinder professionals in investing time in familiarising with the CHILD-profile and adopting it. Another hindering factor is the primary process of data registration within the EMD, CHILD-profile’s data source. This process is time consuming and sometimes leads to incomplete individual health data and consequently to missing data on personalized CHILD-profiles. These missing data and the only short experience with the CHILD-profile might partly explain the variation in the level of use during the study.

The experienced lack of facilitation and prioritisation by CHC-management were in contrast with findings at the level of the socio-political CHC-context: policy makers (including CHC-managers) considered the CHILD-profile to be a promising tool for realizing several relevant goals for the national CHC-context, including stimulating ICF thinking and proper provision of standardized data by the CHC.

This study provided the Dutch CHC-practice with insight in requirements for implementation, in how to target the implementation strategy, and in CHILD-profile’s potential benefits.

The following organisational issues should be prioritized to get ready for local implementation: secure sufficient emphasis on the innovation, facilitate professionals, provide a direct link with the EMD and safeguarding privacy. For implementation on a national level, additional requirements were revealed, like sufficient top down power while maintaining professional autonomy, and a marketing communication plan toward national stakeholders.

Further recommendations for a successful implementation strategy include: clearly display the benefits per target group; offer continuous support to professionals, provide opportunities to exercise with the CHILD-profile in dialogue with colleagues; display which EMD-data are used as data source for the CHILD-profile; and monitor impact of diversity within the target population on usability.

As mentioned earlier, an essential future benefit of the CHILD-profile for CHC is the quick access to structured health data and appropriate representation of child’s health situations. Quick access will save professionals time during child related tasks. Proper representation of health situations facilitates simultaneous thinking processes, which are a prerequisite for the preventive clinical appraisal of a child’s functioning. The segmented EMD-database, which does not display structured health data, currently hinders simultaneous thinking as it forces professionals into a sequential, time-consuming process when retrieving relevant data.

Additionally, and beyond primary expectations, the study revealed points for improving data registration. The CHILD-profile exposes which of the numerous EMD-data entries are relevant for gaining overview on health situations, which are more or less optional for registering detailed background information and which relevant data are currently missing in the EMD. The CHILD-profile stimulated professionals to strive for more consistent data registration and insight in which EMD-data are displayed on the CHILD-profile. This insight could give professionals more control (autonomy) over their access to health data as correct registration of relevant EMD-data would lead to a complete CHILD-profile. Thus, the CHILD-profile can be seen as a motivational tool for setting priorities for EMD-registries and further professionalization toward consistent and structured registrations in accordance with the ICF-CY.

The CHILD-profile would benefit the CHC as well by providing parents online access to a comprehensible summary of the EMD. The CHC currently is not able to commit to their legal duty, since 2020, to provide parents with digital access to EMD’s health data. The recently implemented online CHC-portal for parents merely discloses growth charts and an overall advice. This means that digitally disclosing EMD-registries to parents is rather new for professionals, which might explain the reluctance of some professionals to present the CHILD-profile to certain parents.

The enthusiastic reactions and positive results regarding usability and self-efficacy are in line with results of earlier pilot studies on the CHILD-profile [12, 13]. By introducing the CHILD-profile within real-life practice, this study extended the validation process and generated more profound knowledge, crucial for transitioning from pre-implementation- towards implementation phase [17, 29]. Results reaffirmed the importance of timely mapping determinants at the level of the organisation (as stressed by Fleuren), as well as already known problems like high work load, low staff capacity and time consuming handling of the EMD [10, 21]. In addition to earlier studies, this evaluation provided deeper insight in how time constraints, resulting from these problems, hinder the innovation process and which determinants must be addressed. During previous phases within the longitudinal research project, the focus was predominantly on the determinants of the CHILD-profile itself and its potential users. Much attention was paid on realizing a usable, meaningful visualisation of health data that properly represented the multidimensionality of health, and complied with the standards for human computer interaction [16].

As the practice derived CHILD-profile is unique in providing a holistic and structured display of the complex electronic CHC-data sets in accordance with the ICF-CY framework, results cannot be easily compared to scientific research on other innovations. However, specific findings (e.g. the need for insight in benefits per target group, opportunities to familiarize with the innovation, organisational support, securing data exchange with the existing EMD and safeguarding information transfer) are in line with recently presented guidelines for successful implementation of e-health interventions within health care [30, 31].

This study was a solid and logical step within the multiyear Mixed Methods research project. Integration of complementary quantitative and qualitative data allowed to gain an in depth and broad insight. Triangulation and the opportunity for participants to correct and react on researchers’ interpretations, increased the validity of results.

Purposive sampling of a rather heterogeneous subgroup from the initial study population for the interviews enabled to gain insight in a variety of perspectives, with the limitation that the initial study population was rather small. The limited number of participants and the fact that this study entailed a once-only experience with the CHILD-profile in a pre-implementation phase, were limitations for extensively measuring the level of use. Therefore, it was chosen to focus on measuring the frequency and profundity of use and not yet on evaluating if the CHILD-profile was used as intended and if determinants were associated with the level of use. As it is important for professionals to get acquainted with the CHILD-profile, it might be reasonable to use the profile during regular InterVision group meetings.

The time between experiencing the CHILD-profile and the interviews and focus group was rather long. However, this could have enabled professionals to reflect on findings and preliminary interpretations from a more distant view.

The interviews with parents yielded relatively homogeneous (positive) responses and less in-depth insights. This might be explained by the fact that it was their first and single encounter with the CHILD-profile. During qualitative analysis, it appeared to be essential to put relatively more focus on perspectives of professionals as they must take the first step to integrate the CHILD-profile in practice. Therefore, it was decided to perform a member check focus group with merely professionals. It was anticipated that a member check with parents would not yield substantial new, more in-depth insights for this phase of the innovation process.

This study provided valuable knowledge on how to target the strategy and evaluation of further implementation, as well as on which organisational barriers currently hinder implementation. To appropriately address these barriers, future research is needed to gain better understanding on contrasting findings regarding the experienced insufficient management support versus the positive views of (these) managers on CHILD-profile’s potential and relevance for the CHC-context.

The parallel study on RCT’s feasibility will yield information on recruitment-, response- and retention rates, measure completion and protocol deviations. This information will be used to design future studies on performance and effectiveness of the CHILD-profile within CHC-practice.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated that the 360°CHILD-profile is a useful and efficient tool, compatible with CHC-practice, and that users are competent in handling and using the CHILD-profile within the CHC-context. This study generated valuable knowledge for targeting an implementation strategy and showed which organisational barriers should be addressed to get ready for implementation.

The CHILD-profile, designed according to international standards of human computer interaction for information representation (ISO 9241-12), appears to appropriately represent children’s health situations. The quick overview on holistic health data, provided by the CHILD-profile, is promised to be time saving, to enable a comprehensible transfer of health information to parents, to support clinical reasoning and to stimulate more consistent and structured registry of relevant health data within the CHC. These benefits are essential ingredients for reaching adequate preventive interventions and transformation towards a more predictive, personalized and participative health care.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the participating CHC professionals and parents, as well as the staff of the CHC departments in the Dutch region of South Limburg for their cooperation in designing and conducting the study within their organization.

Funding

This study is supported by ZonMw (grant no. 729410001).

Conflicts of Interest

None declared.

Ethics approval

Approval for conducting this study by was provided by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Maastricht University Medical Centre (no. METC azM/UM 2017-0089; July 2017).

Trial Registration

Netherlands Trial Register NTR6909; https://www.trialregister.nl/trial/6731

Patient consent

All participants gave written informed consent.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [MW], upon reasonable request.

References

- Doove BM, Heller J and Feron FJM (2013) JGZ op de drempel naar gepersonaliseerde zorg. Tijdschrift voor Gezondheidswetenschappen 91, 7:366-7. DOI: 10.1007/s12508-013-0121-5

- Syurina E (2014) Integrating personalized perspectives into Child and Youth Health Care: A long and winding road? PHD thesis, Maastricht University, the Netherlands. ISBN: 978-90-8891-800-1

- Snyderman R, Yoediono Z (2008) Perspective: Prospective health care and the role of academic medicine: lead, follow, or get out of the way. Academic Medicine 83(8):707-14. DOI:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31817ec800

- Snyderman R (2012) Personalized health care: from theory to practice. Biotechnology Journal 7(8):973-9. DOI: 10.1002/biot.201100297

- Pokorska-Bocci A, Stewart A, Sagoo GS et al (2014) 'Personalized medicine': what's in a name? Journal of Personalized Medicine 11(2):197-210. DOI: 10.2217/pme.13.107

- ISO 9241-125 (2017) Ergonomics of human-system interaction — Part 125: Guidance on visual presentation of information.

- Petterson R (2014) Information Design Theories. Journal of Visual Literacy 33(1):1–94. DOI: 10.1080/23796529.2014.11674713

- Greenhalgh T, Potts HWW, Wong G, et al. (2009) Tensions and Paradoxes in Electronic Patient Record Research: A Systematic Literature Review Using the Meta-narrative Method. Milbank Quarterly 87(4):729-88. DOI: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00578.x

- Fragidis LL, Chatzoglou PD (2017) Development of Nationwide Electronic Health Record (NEHR): An international survey. Health Policy Technology 6(2):124-33. DOI: 10.1016/j.hlpt.2017.04.004

- Meuwissen L (2013) E-dossier jgz leidt nog niet tot inzicht [cited 2015 19-06-2015]; Nr. 02:[80-2 pp.]. Available from: http://medischcontact.artsennet.nl/archief-6/tijdschriftartikel/126333/edossier-jgz-leidt-nog-niet-tot-inzicht.htm.

- WorldHealthOrganization (2007) International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, Children and Youth version. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO Press; 289 p. ISBN: 9789241547321

- Weijers M, Bastiaenen C, Feron F et al (2021) Designing a Personalized Health Dashboard: Interdisciplinary and Participatory Approach. Journal of Medical Internet Research; Formative Research 5(2):e24061. DOI: 10.2196/24061

- Weijers M, Feron FJM, Bastiaenen CHG (2018) The 360(0)CHILD-profile, a reliable and valid tool to visualize integral child-information. Preventive Medicine Reports 9:29-36. DOI: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.12.005

- Creswell JW (2018) Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. third edition ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications, Inc. 473 p. ISBN: 9781483344379

- Feilzer MY (2010) Doing Mixed Methods Research Pragmatically: Implications for the Rediscovery of Pragmatism as a Research Paradigm. Journal of Mixed Methods Research 4(1):6-16. DOI: 10.1177/1558689809349691

- Weijers M, Feron F, Van Der Zwet J et al (2021) Evaluation of a New Personalized Health Dashboard in Preventive Child Health Care: Protocol for a Mixed Methods Feasibility Randomized Controlled Trial. JMIR Research Protocols 10(3):e21942. DOI: 10.2196/2194215

- Rothstein JD, Jennings L, Moorthy A et al (2016) Qualitative Assessment of the Feasibility, Usability, and Acceptability of a Mobile Client Data App for Community-Based Maternal, Neonatal, and Child Care in Rural Ghana. International Journal of Telemedicine and Applications 2515420: 14 pages. DOI: 10.1155/2016/2515420

- Fleuren MAH, Paulussen TGWM, van Dommelen P, et al (2014) Towards a measurement instrument for determinants of innovations. International Journal for Quality in Health Care. DOI: 10.1093/intqhc/mzu060

- Arain M, Campbell MJ, Cooper CL, et al (2010) What is a pilot or feasibility study? A review of current practice and editorial policy. BMC Medical Research Methodology 10:67. DOI: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-67

- Moser A, Korstjens I (2018) Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 3: Sampling, data collection and analysis. European Journal of General Practice 24(1):9-18. DOI: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375091

- Fleuren MAH, Paulussen TGWM, van Dommelen P, et al (2014) Measurement Instrument for Determinants of Innovations (MIDI). Leiden, the Netherlands: TNO: https://www.tno.nl/media/6077/fleuren_et_al_midi_measurement_instrument.pdf

- Birt L, Scott S, Cavers D, et al (2016) Member checking: A tool to enhance trustworthiness or merely a nod to validation? Qualitative Health Research 26: 1802-1811. DOI:10.1177/1049732316654870

- Doyle, S (2007) Member checking with older women: A framework for negotiating meaning. Health Care for Women International 28(10): 888–908. DOI: 10.1080/07399330701615325

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018) NVivo (Version 12), https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Boeije H, Bleijenbergh I (2019) Analyseren in kwalitatief onderzoek. Third edition. Utrecht, the Netherlands: Boom. ISBN 978-90-2442-594-5

- Korstjens I, Moser A (2018) Series: Practical guidance to qualitative research. Part 4: Trustworthiness and publishing. European Journal of General Practice 24(1):120-4. DOI: 10.1080/13814788.2017.1375092

- De Brock AJLL, Vermulst AA, Gerris JRM, et al (1992) NOSI, Nijmeegse Ouderlijke Stress Index, Handleiding experimentele versie [NOSI-Nijmegen Parenting Stress Index, Manual experimental version]. Lisse; 21.

- Lundh A, Kowalski J, Sundberg CJ, et al (2010) Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS) in a naturalistic clinical setting: Inter-rater reliability and comparison with expert ratings. Psychiatry Research 177(1-2):206-10. DOI: 10.1016/j.psychres.2010.02.006

- Van Yperen T, Eijgenraam K, Van Den Berg G, et al (2010) Handleiding Standaard Taxatie Ernst Problematiek. Utrecht. Available at: https://www.nji.nl/nl/Kennis/Publicaties/NJi-Publicaties/Handleiding-Standaard-Taxatie-Ernst-Problematiek

- Saldana, L (2014) The stages of implementation completion for evidence-based practice: protocol for a mixed methods study. Implementation Science 9, 43. DOI: 10.1186/1748-5908-9-43

- Cremers HP, Theunissen L, Hiddink J, et al (2021) Successful implementation of ehealth interventions in healthcare: Development of an ehealth implementation guideline. Health Services Management Research. DOI: 10.1177/0951484821994421

Impact Factor: * 4.8

Impact Factor: * 4.8 Acceptance Rate: 69.70%

Acceptance Rate: 69.70%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks