Crèche Toothbrushing Program; Dental Awareness and Perception of Parents and Teachers

Telma Rose*, Leperre S

Dental Public Health Section, Oral Health Services Division, Health Care Agency, Seychelles

*Corresponding Authors: Dr. Telma Rose, Dental Public Health Section, Oral Health Services Division, Health Care Agency, Seychelles

Received: 20 April 2020; Accepted: 28 April 2020; Published: 06 May 2020

Article Information

Citation: Telma Rose, Leperre S. Crèche Toothbrushing Program; Dental Awareness and Perception of Parents and Teachers. Dental Research and Oral Health 3 (2020): 062-073.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

School toothbrushing programs are implemented throughout the world as a means of providing supplementary fluoride to the developing teeth of young children, as prevention against dental caries. Throughout the literature, parental and teacher involvement has been highlighted to be pivotal to the success of school toothbrushing program.

Objectives: the aim of this research is to ascertain parental and teacher awareness and perception of the crèche toothbrushing activity in Seychelles.

Methods: Questionnaire survey of parents and teachers of crèche year two children of the three state schools enrolled in the crèche toothbrushing pilot activity.

Results: 70.2% of parents and 71.4% of teaching staffs of crèche year two children of the three schools completed the respective questionnaire. 72.73% parents stated that their five year old children brush their teeth twice per day but the majority (42.42%) responded that these children brush their teeth by themselves with parental supervision. All parents and teachers participants were aware of the benefits of crèche toothbrushing program and were unanimous that the program should continue, despite differing level of participation by teachers.

Conclusion: Enhanced awareness and motivation for toothbrushing as well as children emerging as positive change agent in the family’s oral hygiene routine emerged as reported positive impacts of the crèche toothbrushing. Co-ordinated effort by all stakeholders is required to address highlighted areas of improvement.

Keywords

<p>Toothbrushing, Awareness, Perception, Knowledge</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Early childhood is recognized as a key period in every child’s development; it is a time of rapid cognitive, emotional, social and physical development, which coupled with the nurturing environment helps to shape the child’s future health and development and the adult that they will eventually become [1, 2]. The same applies to oral health whereby it is now widely accepted that dental behavior and patterns of dental disease during the earlier stages of life is the best predictor of future oral health in adulthood [3]. Henceforth, the primary purpose of dental interventions and programs employed by many countries is to instill positive dental practices in young children earlier in life to help pave the way to a better oral health and related quality of life later in life. Regular toothbrushing is one such positive dental behaviour that the School dental Unit of the Oral Health Services Division has been advocating for as one of the key activities of the National School Oral Health program which was initiated in 1998. Regular toothbrushing is one of the most efficient means of providing the much needed fluoride exposure to the developing teeth of young children. Studies have shown that the long term use of topical fluoride in the form of toothpastes, rinses or varnishes is associated with about 25% lower caries experience [4, 5]. Dental caries is a multifactorial, chronic oral condition affecting people in all parts of the world. Dental caries is by far the most common dental disease affecting young children throughout the world [4, 6-8]. Dental caries has detrimental consequences on children’s quality of life by inflicting pain, premature tooth loss, mal-nutrition and negative influences on growth and development. When the school dental program was initiated, crèche toothbrushing activity was performed as per conventional methods which required wash basin facilities for the children to rinse their mouth after toothbrushing. Since the latter is insufficient in some schools, it led to difficulty and non-sustenance of regular toothbrushing in some schools over the years. As an effort to overcome these constraints and re-vamp this activity, the school dental service, in collaboration with the Institute of Early Childhood Development (IECD), decided to re-introduce a modified dry crèche toothbrushing activity in state schools with lesser requirement of wash basin facilities, whereby the children spat out toothpaste residue in disposable cups or paper napkins rather than rinsing their mouth with water after brushing their teeth. Since beginning of 2019, the modified crèche toothbrushing activity was piloted at three state schools in Seychelles namely Belombre, Au Cap and Grand Anse Mahe schools. It is acknowledged that parents and teachers are key stakeholders of these toothbrushing programs and as such are covered in several evaluative reports. In 2017, 1500 students aged 4-6 years old were enrolled in Dubai’s “MY SMILE” toothbrushing program. According to the evaluation report, 71% of oral health coordinators responded that enforcement from the school administration enhance both teacher and students compliance [9]. The evaluation of a Yorkshire, England toothbrushing program also highlighted that Head Teacher’s role is fundamental to the success of the program and also added on that the involvement of a consistent day-to-day contact person within the schools, is critical to success [10]. However, the literature is slightly conflicted with regards to the importance of direct teaching staffs to the success of toothbrushing programs. In one case, the teachers in Aboriginal communities in Australia perceive their program to be successful because they themselves believed in the program and the long term benefits it entailed [11]. However, other toothbrushing programme facilitators expressed that teachers were not always their contact point and found teaching support workers more able to facilitate the activity [10]. The evaluation also inferred that teachers felt that their role as educators was increasingly being replaced as pseudo-parents with assisted-toothbrushing as another parental responsibility being forced on them. It appears that overall teacher summation of school toothbrushing and their contributory role is most likely dependent on the school dynamic itself including daily school schedule, the age of the targeted children and level of support for the program. In a similar toothbrushing pilot done in a younger school setting targeting 3 to 5 year old children, 95.2% of nursery teachers felt that the activity had enhanced their confidence and knowledge about supervised toothbrushing [12]. The level of flexibility of toothbrushing programs also appears to influence teaching staffs’ perception. In one study, a group of teachers stated that they were able to sustain the toothbrushing program at their school because of the program’s flexibility and adaptability [11] On the other hand, teachers of the “MY SMILE” project reported the ten minute break taken by students to brush their teeth and return back to the class as a disruption to the students’ daily schedule [9] Similarly, facilitators of a school breakfast club toothbrushing pilot also reported time as a limiting factor [13]. But in the case of this amended toothbrushing program which is being piloted in Seychelles, the program facilitators are purposely trying to avoid the busy early morning period or normal classroom hours and have instead proposed that this activity take place during lunch time. Teaching staffs’ perception of school toothbrushing program can also be influenced by the degree of involvement of program facilitators themselves. For example, if the people who have the necessary dental knowledge and skills for the toothbrushing activity are also not actively involved in the program, then this will definitely exert strain on the teaching staffs, who may them resent the program altogether. In the Seychelles context, the program is meant to be implemented by both dental and teaching staffs. This review will be an insight as to what the teaching staffs perceived of this partnership. With regards to parental views, the literature reports that most parents are positive about school toothbrushing programs and suggested that the program be continued [9, 10]. In terms of added benefit, parents also felt that the toothbrushing pilot has rendered the process of toothbrushing less difficult for their child [12]. However, the literature also reported that some parents exhibited concerns about cross infection control relating to storage of toothbrushes in schools [9]. This suggests that precise information about the standards and safety of school toothbrushing may not have been relayed to parents causing these concerns but these could also be inherent. Other school toothbrushing facilitators found that some parents do not necessarily attend the toothbrushing information session or even other health-related sessions, which could enhance non-understanding and concerns of the activity [10]. School toothbrushing program has been implemented in Seychelles for many years but there has never been a formal evaluation exercise done to find out what teachers and parents perceive of the program itself. These perceptions are key influencers of the success of toothbrushing program and therefore need to be evaluated and if required, addressed before full scale implementation of the program in other schools.

1.1 Aims and objectives

The aim of this project was to provide parental and teacher feedback about a crèche toothbrushing activity which was being piloted in three state schools in Seychelles.

Objectives

- To ascertain parental and teacher perception of the crèche toothbrushing pilot activity.

- To understand the home dental hygiene routine of children involved in the crèche toothbrushing pilot activity.

- To assess the level of teacher involvement in the crèche toothbrushing activity.

2. Methods

Research can be conducted according to a qualitative, quantitative or mixed methodology approach. This crèche toothbrushing evaluation project mostly followed a quantitative research approach with a few open-ended questions. The evaluation project was conducted in two phases and targeted all crèche teaching staffs and parents of crèche year two children of the three state schools piloting the crèche toothbrushing program, namely Belombre, Au Cap and Grand Anse Mahe School. Sample frame is the group of individuals that can be selected from the target population given the sampling process used in the study [14]. Usual research protocol requires prospective study participants to be sampled from the sample frame as per selected sampling strategy. However, since the targeted group of crèche teaching staffs is already small, it was decided that an all-inclusion rule will apply. This is similar to the total population sampling scenario whereby the entire population is studied because the size of the population that has the particular characteristics of interest is very small. 14 self-administered teacher questionnaires and research information sheet were given to the crèche teacher-in-charge of the three schools, who in turn distributed the questionnaires to their respective crèche year two teaching staffs All completed questionnaires were sealed in the provided envelopes and forwarded to the teacher-in-charge’s office and was later collected by the main researcher. Questionnaire is one of the most commonly used data collection tool as it facilitate the collection of data from a large number of study participants and at a relatively lesser cost compared to other mode of data collection such as interviews. The teacher questionnaire included demographic questions about age and gender and specific questions about participants’ involvement and views about the crèche toothbrushing activity. Similarly, a total of 94 copies of the parent questionnaires with information sheet and sealing envelopes were also distributed to the three crèche teacher-in-charge. The number of parents targeted reflected the number of crèche year two children in the three schools as at the end of school term two. The crèche teacher-in-charge then distributed the questionnaires to their respective crèche year two teachers who issued one questionnaire to one of the parent of the crèche year two children who attended the school open day. For those children whose parents did not attend the open day, the questionnaire pack was given to the parents when they came to pick up their children after school. Given the possibility of low response rate, it was decided that rather than applying a sampling strategy, all parents of crèche year two children of the piloted schools will be targeted. The parent questionnaire included demographic questions about age and gender and specific questions for parents about their child’s dental hygiene habits at home and their views about the crèche toothbrushing activity. The quantitative data generated from the close-ended questions of the questionnaire was entered into a Microsoft Excel database and analysed through basic descriptive statistics. The qualitative responses from the open-ended questions were entered into a Microsoft Word document and was subsequently analysed for common themes by the main researcher and an associate staff.

3. Results

66 parents and 10 teaching staffs of crèche year two children of the three schools completed the respective questionnaire, corresponding to a response rate of 70.2% and 71.4% respectively.

|

Gender |

Age range |

||||||||

|

Female |

Male |

Unspecified |

20-30 |

31-40 |

41+ |

Unspecified |

Total |

||

|

Au Cap |

24 |

3 |

10 |

9 |

6 |

2 |

27 |

||

|

Belombre |

20 |

2 |

7 |

10 |

4 |

1 |

22 |

||

|

Grand Anse Mahe |

14 |

2 |

1 |

6 |

9 |

1 |

1 |

17 |

|

|

Total |

58 |

7 |

1 |

23 |

28 |

11 |

4 |

66 |

|

Table 1: Demographic information parent participants.

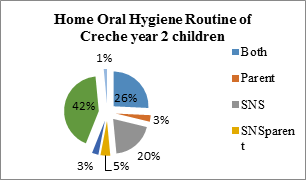

Figure 1: Home oral hygiene routine of crèche year two children participants (Both= child brushes by himself AND then parent brushes child’s teeth once again, SNS= child brushes by himself without supervision, SWS= child brushes by himself with parent supervision, Parent= parent brushes child’s teeth)

|

Toothpaste type |

|||||

|

Frequency of toothbrushing |

Adult toothpaste Fluoride |

Adult toothpaste no fluoride |

Adult Fluoride toothpaste + child toothpaste |

Child toothpaste |

Total |

|

Once |

4 |

1 |

2 |

7 |

|

|

Twice |

21 |

2 |

2 |

23 |

48 |

|

Three times |

5 |

2 |

3 |

10 |

|

|

Never |

1 |

1 |

|||

|

Total |

30 |

3 |

4 |

29 |

66 |

Table 2: Home oral hygiene practice of crèche year two children participants.

|

Yes |

No |

NA |

|

|

Overall participation in crèche toothbrushing activity |

8 |

2 |

|

|

Accompanying children to specific toothbrush area |

5 |

3 |

2 |

|

Apply toothpaste to toothbrush |

6 |

2 |

2 |

|

Brush the teeth of crèche children |

4 |

4 |

2 |

|

Rinse toothbrushes after children has brushed teeth |

4 |

4 |

2 |

|

Supervise crèche children during toothbrushing |

6 |

2 |

2 |

Table 3: Crèche teacher level of participation in selected item of crèche toothbrushing activity.

|

Parent |

Teacher |

|||||

|

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Unsp. (%) |

Yes (%) |

No (%) |

Unsp. (%) |

|

|

Have you received sufficient information on the crèche toothbrushing activity |

86 |

7.6 |

6 |

100 |

- |

- |

|

In your opinion, do you think the Oral Health Services Division should continue with this crèche toothbrushing activity |

100 |

- |

- |

100 |

- |

- |

|

Has this crèche toothbrushing activity made an impact on the oral hygiene routine of your family |

73 |

27 |

- |

90 |

10 |

- |

Table 4: Parental and teacher perception of the crèche toothbrushing activity.

Findings of the open-ended questions about parental and teacher perception of the crèche toothbrushing activity. All the parent participants agreed that the crèche toothbrushing activity should continue. The importance of this activity in terms of encouraging good toothbrushing behaviour and increased awareness of toothbrushing itself were highlighted.

- That activity is a good initiative because it encourages children and the importance of toothbrushing. (Female parent, Belombre)

- Because it makes the small children who don’t like to brush their teeth, get the courage to brush theirs when they see other small friends brushing and it makes them get the good habits at home too. (Female parent, Grand Anse Mahe)

The noticeable positive change in awareness and willingness for toothbrushing amongst crèche children also emerged as a reason why parents believe the crèche toothbrushing activity should continue.

- Compared to earlier, my child has more information and willingness to brush his teeth, he has understood that this needs to be done every day and because it’s good to start this when children are still small. (Female parent, Belombre)

Parents also suggested that the toothbrushing activity should continue as the children progress through primary school

- But it’ll be better if they continue as these children go to primary school. (Female parent, Grand Anse Mahe)

- But not just crèche, other primary school children, what happens to them. If, when my child goes to primary school, are they going to continue with this activity? (Female parent, Au Cap)

A few parents perceived that the crèche toothbrushing activity will make their children achieve independent toothbrushing.

- For children to get more used to continue brushing by themselves (Female parent, Au Cap)

75% of the parent participants responded that the crèche toothbrushing activity has had an impact on their family’s oral hygiene routine. These parents reported that their children are more aware and are communicating the importance of toothbrushing to the other family members and are also more confident in self toothbrushing

- Because he came to show us the way he’s been shown at school for us to do the same also when we’re brushing our teeth (Female, Belombre)

- He talks about it a bit often at home and sometimes he asks the other members of the family if they’ve brushed their teeth. It is something positive for the adults, that sometimes we forget those important information (Female, Belombre)

- My child is more interested in brushing by himself without my supervision (Female, Au Cap)

The parents also reported that the crèche toothbrushing activity has also brought about a change in their own oral hygiene routine

- Because by habit we all brushed our teeth just once, now we find ourselves brushing two times per day (Female, Grand Anse Mahe)

- It helps the family change the way that we were brushing our teeth (Female, Grand Anse Mahe)

A few parents felt that the crèche toothbrushing activity did not have such an impact on the family’s oral hygiene routine.

- When he’s at home, he does the way he’s use to do (brush the teeth and rinse the mouth) (Female parent, Grand Anse Mahe)

- We just been doing what we do. I always make sure my kids’ mouths are clean (Female parent, Au Cap)

Some teachers also responded that they contributed to the crèche toothbrushing activity by informing the children when to go to the dental staffs on site, whilst one teacher stated that she did not participate because the dental staffs did the activity themselves.

- I tell them when it’s time to go to the dentist (Teacher, Grand Anse Mahe)

- The dentist came and did the activity by themselves which is really good (Teacher, Grand Anse Mahe)

All the crèche teaching staffs participants’ were unanimous that the Oral Health Services Division should continue with the crèche toothbrushing activity. The majority of teachers believe that this activity will help children take better care of their teeth and have improved oral health.

- Through that the children have improve a bit because of that program. It gave the children the opportunity to take good care and know the ways to brush the teeth (Teacher, Belombre)

- Because we noticed that children have better oral health since we’ve started this program (Teacher, Au Cap)

However, some teachers felt that crèche toothbrushing should not be the sole responsibility of teachers, and that parents or a designated person should carry out this activity.

- But someone special should come and do this activity with the children. Crèche teachers don’t even get time for tea break (a little moment just for eating) teachers are tired or let their parents show them toothbrushing (Teacher, Grand Anse Mahe)

The majority of crèche teaching staffs responded that the crèche toothbrushing activity has had an impact on their own oral hygiene routine. The main changes commented on by the teachers is that they are now not rinsing their mouth with water after toothbrushing.

- I stopped rinsing after toothbrushing, I just spit out (Teacher, Grand Anse Mahe)

- Put a little bit of toothpaste on the toothbrush, the type of toothbrush that we use, don’t rinse your mouth when you’ve finished brushing to get into the habit (Teacher, Belombre)

4. Discussion and Analysis

The main purpose of this study was to ascertain parental and crèche teaching staffs perception of the crèche toothbrushing activity, which was being piloted at three state schools. There was a gender imbalance with regards to the participants in that 87.88% of the parent participants and all crèche teaching staffs were females. This was expected especially since mothers are the parents who usually take on the role of school-related duties and the teaching staffs’ composition in Seychelles; more specifically at crèche level is predominantly females. As described in the methodology chapter, the number of parents targeted was driven by the actual number of crèche year two children in each of the three schools, which helps to explain the imbalance in number of targeted parents from each school. However, on individual school level, there were differences in parents’ response rate, with Belombre school recording the highest parent participation rate (91.67%), followed by Grand Anse school (73.91%) and Au Cap school yielding the lowest response rate of 57.45%. This could be due to differential parent attitude towards research itself or their existing relationship with their children’s respective schools. The first two questions required parents to comment on their crèche year two children’s’ home oral hygiene routine as well as the specific type of toothpaste used. This was primarily to gauge whether toothbrushing routine established at school through this pilot was being supplemented at home. The majority of parents responded that their crèche year two children brush their teeth by themselves with parental supervision (42.42%) whilst 19.7% responded that this self-toothbrushing is achieved without supervision. These responses should be of great concern to the dental staffs who are providing regular dental care to these children, because this lack of parental involvement could negate all preventive efforts done by the dental therapists, especially if these children’s level of oral hygiene is not ideal or if their dietary routine is leaning towards high caries risk. In Seychelles, the Oral Health Services Division advocate for parents to allow their crèche children to brush their teeth by themselves followed by a subsequent “touch up” toothbrushing by the supervising parent on site. This is because at this age, the child’s manual dexterity and the proper toothbrushing technique are yet to be at the optimum level. In this study, only 25.76% of parents are fulfilling this task. Two parents also stated that they themselves brush their children’s’ teeth. This practice should also not be encouraged because if the parents continue to do this task themselves, the child may be less able to adapt to self-toothbrushing through the correct technique later on and thus be at a disadvantage. The majority of parents (72.73%) reported that their crèche year two children brush their teeth twice a day. Usage of regular adult fluoride toothpaste and child toothpaste seems to be fairly similar. This should serve as a reminder to the Oral Health Services Division (Health Care Agency, Seychelles) of the need to discuss and formalise guidelines on suitability of toothpaste to be used by children of different age groups and how best to promote this message to parents. The fundamental difference between the two types of toothpaste lies in their fluoride content, in that the child toothpaste has a much lower fluoride content level than the adult fluoridated toothpaste. The issue of type of toothpaste used is important in this case, since the essence of this project is to provide maximum fluoride exposure to these developing teeth. It is important that optimum fluoride exposure provided during the school toothbrushing activity be sustained at home. The fluoride content of toothpaste is also important especially since some of these children who are enrolled in the pilot have already experience tooth decay. Another objective of this study was to find out parental perception of the crèche toothbrushing activity. The bulk majority of respondents stated that they are satisfied with the crèche toothbrushing activity and that this activity should be continued. This is synonymous to the studies discussed in the literature review. This shows that parents support this program but nonetheless, need additional guidance from dental staffs especially with regards to the previous findings pertaining to crèche children brushing their teeth by themselves with or without supervision. Some parents suggested that school toothbrushing should not only be limited to crèche level but that it should be continued through primary school. This is a good proposition in a sense that it will help to maintain continuous and good oral hygiene but resources are constrained. For example, dental staffs have other competing clinical and program-related duties which render it difficult for them to be physically on site at the schools and teachers have already pointed out their time limitations. The toothbrushing resources namely toothbrushes and storage racks may also be a limiting factor, if aiming to extend the toothbrushing activity throughout primary school. This proposition can only be implemented through shared responsibility of all parties along with self-sacrifice, motivation and careful balancing of other duties. Aside from dental staffs and teachers, parents and the community itself must be willing to contribute, such as through sponsorship of toothbrushing resources. A few parents also perceived that the crèche toothbrushing activity will make their children achieve independent toothbrushing. This perception is two-fold; on one hand, it will be good if the child can take up toothbrushing in the absence of the parent but on the other hand, this child is not yet at that age for independent toothbrushing and parental supervision and assistance is still necessary. he teachers were also unanimous that the crèche toothbrushing program should continue. However, this response conflicted with some questions that were put to them about their level of participation in this activity. 80% of teachers stated that they participated but with differing level of involvement in each tasks. Five out of the ten teachers stated that they accompanied the children to the designated toothbrushing area whilst 3 participants responded no. These responses may also be attributed to specific school setting and the way the activity was done. For example, at one school it was observed that the toothbrushing activity was done in a separate dental room on the school campus, which required the children to walk from their classroom for toothbrushing, whilst the other schools, toothbrushing was done within the immediate commune area of the crèche itself. However, differing location should not be a barrier to teachers accompanying children for toothbrushing. In this case, the level of motivation of the teachers may have been a contributing factor. Interestingly, some teachers responded further on this by saying that they participated by informing the children when to go to the dental staffs on site for toothbrushing, which a lay observer would disagree and simply label this as a passive undertaking. But in this case, this appears to be due to a lapse of communication or unclear role allocation. There is a possibility that these teachers were not informed that they need to participate fully in this project or it could be that the teachers saw the dental staffs doing the activity themselves and thus decided that their participation is not needed. Additionally, some teachers responded that the crèche toothbrushing activity should not be the sole responsibility of teachers and that parents or a designated person should perform this activity. This response is justifiable to some extent but the teachers should not remove themselves completely out of this role because after all, the crèche toothbrushing activity is being implemented in the school where they work and they will also benefit when these children have improve oral hygiene and overall oral health. This questioning of the role of teachers in school toothbrushing activities is similar to the findings of Woodall et al (2014) study but unfortunately in this study, it was difficult to ascertain whether this response came from the teachers or the teacher assistants themselves. The questions about specific toothbrushing tasks involving more direct contact with children’s saliva such as the actual action of brushing children’s teeth or rinsing of toothbrushes following toothbrushing generated mixed responses. This is understandable given that some people perceive saliva itself or any object that comes into contact with saliva to be dirty. Dental staffs should address this belief and educate the teachers about the cross-infection control guidelines that they should adhere to when conducting this activity. This is crucial because these two tasks are the essence of toothbrushing itself and needs to be fully achieved by whoever is implementing the toothbrushing program. The participants also commented on the adequacy of information provided. All the teachers agree that the information provided was sufficient. 86% of parents responded that they have received sufficient information about the crèche toothbrushing activity. The other parents wanted to know about the specific toothbrushing techniques being used as well as feedbacks on their children’s progress in this activity. This reinforces that dental staffs need to remain in direct communication with the parents and need to agree on the best mechanism to impart information in both clinical and non-clinical settings. When questioned about the impact of the crèche toothbrushing activity, 73% of parents commented that activity has brought about positive change on their family’s oral hygiene. The parents elaborated that the activity has led to noticeable changes in their children, in terms of greater awareness and confidence at toothbrushing but the added bonus is that their children are also bringing other changes to the family by communicating the importance of toothbrushing and motivating other family members to brush. This reinforces the doctrine that instilling positive dental behaviour of toothbrushing at younger age is well-received by these children, who will definitely pass it on to the family. The parents have also reported that the crèche toothbrushing activity has also brought a change in their own oral hygiene routine. This is testament that the toothbrushing program which was initiated in schools has now shifted to the home environment with the crèche children as the primary change agent. Dental staffs should thus consider children in future dental preventive endeavors targeting the family. However, a few parents felt that the crèche toothbrushing activity did not have such an impact on their routine. This could be due to the fact that the family’s oral hygiene routine was already adequate and needed no improvement or it may well be that family support and the environment was not ideal for the child to apply the technique and skills gained at school within the home environment. On the other hand, the majority of teachers reported a change in their own oral hygiene routine, in that they have now adopt the habit of not rinsing the mouth with water following toothbrushing, which is not something to adapt to easily as adults.

5. Conclusion

This study has highlighted that both parents and teachers of crèche children of the three piloted schools are in favour of the crèche toothbrushing activity and wants the program to continue. Enhanced awareness and motivation for toothbrushing as well as children emerging as positive change agent in the family’s oral hygiene routine emerged as reported positive impacts of the crèche toothbrushing. The study has also uncovered some areas of improvement which can only be addressed through coordinated efforts of parents, teachers and dental staffs.

References

- Marmot, M. Fair Society, Healthy Lives: The Marmot review, strategic review of health inequalities in England Post 2010, London (2010).

- Prevention and early intervention in child health services: the foundations of a healthy adult life are laid in early childhood, Policy Paper, Prevention & Early Intervention Network (2019).

- Vargas C, Ronzio, C. Disparities in early childhood caries, BMC Oral Health, 6 (S3) (2006).

- Sheiham A, James WP. A reappraisal of the quantitative relationship between sugar intake and dental caries: the need for new criteria for developing goals for sugar intake. BMC public health 14 (2014): 863.

- Sheiham A. Dietary effects on dental diseases. Public health nutrition 4 (2001): 569-591.

- Jokic NI, Bakarcic D, Jankovic S, et al. Dental caries experience in Croatian school children in Primorsko-Goranska county. Central European journal of public health 21 (2013): 39-42.

- Sheiham A, James WP. A new understanding of the relationship between sugars, dental caries and fluoride use: implications for limits on sugars consumption. Public health nutrition 17 (2014): 2176-2184.

- Petersen PE. The World Oral Health Report 2003: continuous improvement of oral health in the 21st century – the approach of the WHO Global Oral Health Programme. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology 31 (2003): 3-24.

- Almashhadani S. My Smile-Toothbrushing program for school children in Dubai, UAE, Oral Health Database (2017).

- Woodall JR, Woodward J, Witty K, et al. An evaluation of a toothbrushing programme in schools. Health Education Journal 114 (2014): 414-434.

- Dimitropoulos Y, Holden A, Sohn W. In-school toothbrushing programs in Aboriginal communities in New South Wales, Australia: A thematic analysis of Teacher’ perspectives (2019).

- Bennett E. Supervised Toothbrushing Pilot Programme, September-December 2017, review Summary Document (2018).

- Graesser HJ, Martin-Kerry JM, De Silva A, et al. Assessing the feasibility of a supervised toothbrushing program within breakfast clubs in Victorian Primary schools, Australian & New Zealand Journal of dental and Oral Health 7 (2018): 5-10.

- Martinez-Mesa J, Gonzalez-Chica D, Duquia R, et al. Sampling: How to select participants in my research study, Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 91 (2016).

Impact Factor: * 3.1

Impact Factor: * 3.1 Acceptance Rate: 76.66%

Acceptance Rate: 76.66%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks