Isolation, Characterization and Hydrogen Sulfide H2S Sorption Properties at Room Temperature of Magnetite Sludge from Radiator

Panagiotis Ziogas1, Alexios P Douvalis1, Athanasios B Bourlinos1*, Christina Papachristodoulou1, Nikolaos Chalmpes2, Michael A Karakassides2, Aris E Giannakas3, Constantinos E Salmas2*

1Physics Department, University of Ioannina, 45110 Ioannina, Greece

2Department of Materials Science & Engineering, University of Ioannina, 45110 Ioannina, Greece

3Department of Food Science and Technology, University of Patras, 30100 Agrinio, Greece

*Corresponding author: Athanasios B Bourlinos, Physics Department, University of Ioannina, 45110 Ioannina, Greece. Tel: +302651008511

Received: 18 June 2022; Accepted: 24 June 2022; Published: 29 June 2022

Article Information

Citation: Panagiotis Ziogas, Alexios P Douvalis, Athanasios B Bourlinos, Christina Papachristodoulou, Nikolaos Chalmpes, Michael A Karakassides, Aris E Giannakas, Constantinos E Salmas. Isolation, Characterization and Hydrogen Sulfide H2S Sorption Properties at Room Temperature of Magnetite Sludge from Radiator. Journal of Nanotechnology Research 4 (2022): 97-110.

DOI: 10.26502/jnr.2688-85210032

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Radiator sludge is caused by hydrothermal corrosion of ferrous metals that make up the system, with more than 98 % being magnetite Fe3O4 (e.g., magnetite sludge). When hot circulating water reacts with metals such as the steel inside radiator, the build-up of sludge can be costly, leading to heating inefficiency or system breakdown through pipes blockage. Therefore, the sludge must be removed from radiator on a regular basis, ending up as waste to the environment without any further use. Taking into account the numerous applications of magnetic iron oxides, as well as the vast number of installed radiators existing worldwide, it becomes apparent that magnetite sludge makes a considerable yet cheap waste meriting further attention towards practical applications. In this work, we isolate and characterize magnetite sludge from radiator, providing evidence about the magnetic nature of the iron oxide phase for the first time. Following, we exploit the sludge as sorbent material towards hydrogen sulfide H2S removal. Due to trace amounts of catalytic elements in the sample from the steel body of radiator, this shows a high removal capacity of 2.68 mmol H2S per gram of sorbent at room temperature, thus surpassing literature-reported values of synthetic magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles (0.1-1.5 mmol H2S per gram of sorbent in the range 30-120 °C). This finding is important taking into consideration that there is an ever-increasing need towards an efficient removal of hydrogen sulfide H2S at room temperature by low-cost sorbents.

Keywords

<p>Magnetite; Radiator sludge; 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy; Magnetic iron oxides; Hydrogen sulfide sorption</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Magnetite Fe3O4 is a term used in plumbing to describe the black iron oxide sludge often seen in radiator water. The solid derives from hydrothermal corrosion of the steel body of radiator by hot circulating water (3 Fe + 4 H2O à Fe3O4 + 4 H2), and as it builds-up, creates a number of potential problems, such as blockages and reduction in heating efficiency. In order to ensure a steady operation and avoid system breakdown, the sludge has to be removed usually by venting/flushing. In this case, the obtained blackish water containing suspended magnetite Fe3O4 particles is right after discarded without any further use. Although radiator sludge is known among technicians, no report in the literature deals or even discusses on the structural features and application aspects of this inexpensive waste material. This is quite surprising when considering that magnetite Fe3O4 holds numerous applications in magnetic recording, pigments, catalysis, ferrofluids, biomedicine and wastewater treatment [1-6]. In striking contrast, other iron-rich wastes, such as red mud, have been extensively studied and explored instead, as for instance in construction industry, catalysis or environment [7-11]. In the case of red mud one may argue that this is a massive and cheap byproduct of worldwide aluminum production; nevertheless, since there is an enormous number of globally installed radiators in houses, hotels, working places etc., the amount and low cost of magnetite sludge that could be potentially collected should not be neglected, albeit rough estimates are missing from the literature. Hydrogen sulfide H2S is a smelly, irritating and corrosive contaminant present in crude petroleum, natural gas and biogas. It is also found as a pollutant in air due to the hydrolysis of metal sulfides rocks, anaerobic respiration, rotten vegetation and hydrodesulfurization of gasoline. Therefore, the removal of hydrogen sulfide H2S from fuel sources or air has become a great necessity, and to this aim, several inexpensive materials and methods have been developed in this context [12-14]. Among them, nanostructured iron oxides, including magnetite Fe3O4, are potential sorbents for desulfurization, due to their low cost and good sorption properties, the latter based on the surface chemical reaction between hydrogen sulfide H2S and iron oxide towards the formation of iron sulfide FeS. In addition, it is possible to regenerate the sorbent by mild heating of the iron sulfide layer in air (4 FeS + 7 O2 à 2 Fe2O3 + 4 SO2) [15-21]. However, still remains a great challenge to achieve better removal capacities at low temperature, preferably at room temperature. This is mainly due to the fact that the involved chemisorption phenomena between iron oxide and hydrogen sulfide H2S are generally favored at high temperature due to kinetical barriers. Based on these grounds, herein we have isolated and characterized magnetite sludge from radiator for the first time. The structure, composition, size and morphology of the isolated solid were confirmed by X-ray diffraction, X-ray fluorescence, atomic force microscopy, 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy and magnetic measurements. The iron oxide waste was tested in hydrogen sulfide H2S removal, showing much better sorption capacity at room temperature than that of literature-reported synthetic magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the range 30-120 oC. The better performance in this case is mainly ascribed to the catalytic presence of trace elements in the sludge from the steel body of radiator. The low cost and relatively high removal capacity of magnetite sludge make this waste an appealing sorbent towards hydrogen sulfide H2S removal at low temperatures.

2. Materials and Methods

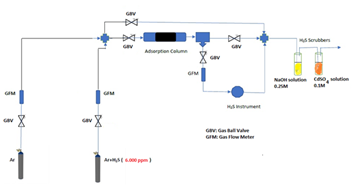

Radiator sludge was isolated from the blackish water collected through venting by centrifugations and washings with water and acetone prior to drying. Every liter of blackish water afforded 0.5-1 g of sludge in the form of a strongly magnetic black solid (N2 BET specific surface area = 10 m2 g-1). It is important to note that the amount of magnetite sludge within radiator is even greater than that isolated by venting, as most of the solid tends to build up at the bottom of the metallic body. The sitting sludge can be fully collected only after disconnecting and draining the whole metallic body or through pump power flushing. A handmade apparatus, the flow chart of which is depicted in Scheme 1, was used for hydrogen sulfide H2S removal evaluation. Adsorption experiments were conducted in a 4 mm inner diameter stainless steel 316 reactor at atmospheric pressure and ambient temperature 25 °C.

Scheme 1: Handmade experimental apparatus for hydrogen sulfide H2S sorption experiments.

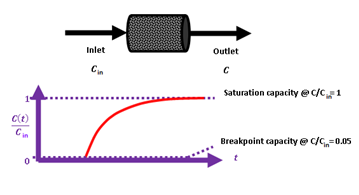

Breakthrough measurements were carried out under the following conditions. The inlet hydrogen sulfide H2S concentration was Cin = 53 ppm in a mixture with high purity argon gas (> 99.999 %). The height of the sorbent bed was 3.3 cm and the contained sorbent mass was 0.5411 g. A schematic illustration of inlet-outlet streams and of a breakthrough curve is illustrated in Scheme 2.

Scheme 2: Schematic illustration of the experimentally developed breakthrough curve.

The volumetric gas flow rate was = 9.43 mL min-1 while the gas hourly space velocity was GHSV = 1853 h-1. The outlet hydrogen sulfide H2S concentration was measured continuously using an Xgard Bright gas detector instrument provided by CROWCON Ltd. and recorded using an akYtec MSD200 data logger provided by akYtec GmbH. The breakpoint time was considered as the time elapsed until the hydrogen sulfide H2S outlet concentration reached 5 % of the inlet concentration. The breakthrough q(tb) and the saturation q(ts) sorption capacity were calculated according to equation 1 which was proposed by Castrillon et al. [22].

where Cin (mgH2S L-1) is the hydrogen sulfide H2S concentration in the inlet stream, mads (g) is the adsorbate mass, (mL min-1) is the gas stream flow rate, C(t) (mgH2S L-1) is the hydrogen sulfide H2S concentration in the outlet stream, t (min) is the time passed since the gas flow started, ε is the sorbent bed porosity, and Vads (mL) is the sorbent bed bulk volume. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) was conducted on background-free Si wafers using Cu Kα radiation from a Bruker Advance D8 diffractometer. Elemental analysis was performed using radioisotope-induced X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) spectroscopy. Annular radioisotopic 109Cd and 241Am sources were used for sample excitation, fixed coaxially above a Si(Li) detector in a 2π geometry. Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) images were obtained in tapping mode with a Bruker Multimode 3D Nanoscope (Ted Pella Inc.) using a microfabricated silicon cantilever type TAP-300G, with a tip radius of < 10 nm and a force constant of approximately 20-75 N m-1. 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum was collected in transmission geometry at 300 K using constant-acceleration spectrometers, equipped with 57Co(Rh) sources kept at room temperature. Velocity calibration of the spectrometers was carried out using metallic α-Fe at 300 K and all Isomer Shift (IS) values are given relative to this standard. The experimentally recorded spectra were fitted and analyzed using the IMSG code [23]. Magnetic measurements in powdered form (e.g., magnetization M versus applied magnetic field H) were carried out at room temperature using a Vibrating Sample Magnetometer (VSM) Lakeshore model 7300.

3. Results and Discussion

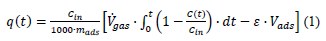

The XRD pattern of radiator sludge is presented in Figure 1. The pattern exhibits well defined and relatively sharp diffraction peaks, indicating high crystallinity for the sample. In particular, the diffraction peaks at 18.4, 30.2, 35.6, 43.2, 57.2 and 62.6 degrees 2θ, correspond to the atomic diffraction planes of the ferrimagnetic spinel-type structure of either magnetite Fe3O4 or maghemite γ-Fe2O3 (ICDD PDF 00-019-0629 or 00-039-1346 respectively) [24], both sharing similar XRD patterns. Nevertheless, by a closer look at the diffraction peaks, these seemed to better match the magnetite Fe3O4 phase. More elucidating information about the exact nature of the iron oxide phase present in the sample is provided below using 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy. Lastly, the average crystalline domain size of the iron oxide spinel-type phase in the sample was approximately estimated via the Scherrer formula [25] to be 34 nm, as derived from the diffraction peaks with the larger intensities.

Figure 1: XRD pattern of radiator sludge. The peak positions of the magnetite and maghemite spinel-type phases taken from the corresponding ICDD pdfs and the Miller indices (hkl) of the corresponding atomic diffraction planes for the magnetite phase are also included.

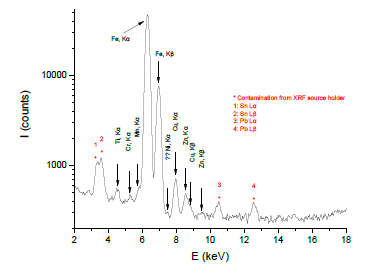

The qualitative elemental composition of radiator sludge was determined by means of XRF spectroscopy. The prevailing characteristic elemental energies that compensate for the displaced electrons from their atomic orbital positions are registered in Figure 2. From this spectrum the element of iron (Fe) possesses the greatest contribution; residual or additive elements from the steel body of radiator, like Copper (Cu), Zinc (Zn), Manganese (Mn), Chromium (Cr) and Titanium (Ti), were additionally observed in the sample, however, to a less extent. Particularly the presence of Cu, Zn and Cr in the sample may assisting its hydrogen sulfide H2S removal capacity at room temperature, as it is discussed below.

Figure 2: XRF spectrum collected from radiator sludge.

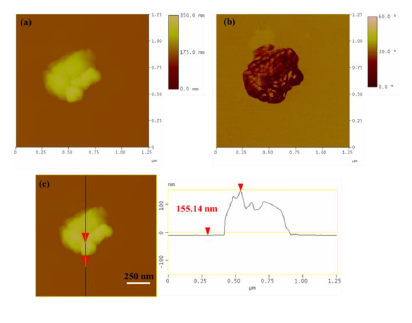

AFM images were also collected in order to study the morphological properties and interconnection of the particles present in the sample (Figure 3). Accordingly, the sludge presented a uniform spatial distribution of roughly spherical shaped particles with a particle size distribution attributed to particles with average diameter of 17 nm. This average particle size was less but comparable to the average crystallite size obtained above from X-rays and the approximate Scherrer formula (34 nm). The observed discrepancy is common in the literature and mainly stems from the fact that XRD does not distinguish between particle and grain sizes, especially when strong aggregation forces occur between particles towards large grains. Indeed, AMF confirmed the presence of such aggregates as a result of strong magnetic interactions between individual particles. Figure 4 characteristically shows a massive cluster of aggregated particles with thickness of 155 nm. Although such extremely large clusters were rarely observed in the sample, this information is indicative of the strong tendency of the magnetic particles to form large agglomerates.

Figure 3: (a) AFM image of single particles in radiator sludge; (b,c) the morphology and size of the particles are more distinguished along with the performed cross section analysis of a particle; (d) particle size distribution based on statistical analysis of several numbers of particles.

Figure 4: (a) AFM image of an aggregated cluster in radiator sludge; (b) morphology and angular position of the cluster; (c) performed cross section analysis of the cluster.

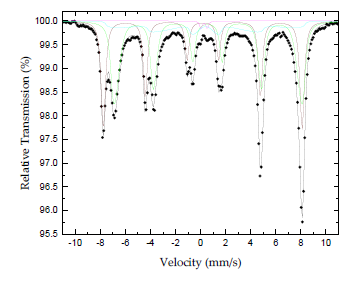

The nature of the iron-containing phase in the sample was conclusively elucidated by means of the atomic-level-probing technique of 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy. The 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of the sample recorded at room temperature (300 K) is shown in Figure 5. The corresponding hyperfine parameters are listed in Table 1. It is well known that magnetite Fe3O4 adopts the inverse spinel-type structure [Fe3+(Fe3+Fe2+)O2-4] yielding a spectrum at room temperature which is composed of a superposition of contributions corresponding to iron ions in different crystallographic sites (A and B), as well as in different electron valence states (Fe3+ and Fe2.5+ respectively) [26]. At temperatures above TVerway = 119 K (for bulk magnetite Fe3O4) the iron ions (Fe3+ and Fe2+) in the B sites of the crystal lattice are in an electron hopping state, making preferable to consider them as Fe2.5+ ions, which could account for a sextet with assimilated intensity in the spectrum [27-29]. Thus, one sextet accounts for Fe3+ ions in the A sites and one sextet corresponds to Fe2.5+ ions in the B sites of the crystal lattice. These components are dominating the spectrum.

Figure 5: Mossbauer spectrum of radiator sludge at room temperature (300 K).

|

Site-Phase |

IS (mm/s) |

Γ/2 (mm/s) |

QS or 2ε (mm/s) |

Bhf (kOe) |

ΔBhf or |

A (%) |

Color |

|

|

Magnetite Fe3+ A-sites |

0.28 |

0.18 |

-0.01 |

498 |

3/0 |

36 |

Brown |

|

|

Magnetite Fe2.5+ B-sites |

0.68 |

0.22 |

0.05 |

478 |

12/0 |

46 |

Green |

|

|

SPM or PM Fe3+ |

0.38 |

0.11 |

0.51 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

Magenta |

|

|

Collapsing Bhf Magnetite |

0.50 |

0.14 |

-0.01 |

488 |

114/0 |

17 |

Cyan |

Table 1: Mossbauer parameters of radiator sludge collected at room temperature (300 K). IS is the isomer shift (relative to α-Fe at 300 K), Γ/2 is the half line-width, QS is the quadrupole splitting, 2ε is the quadrupole shift, Bhf is the central value of the hyperfine magnetic field, ΔBhf is the spreading of Bhf and A is the relative spectral absorption area of each component, assignment and color of which are discussed in the text. Typical errors are ± 0.02 mm/s for IS, Γ/2, 2ε and QS, ± 3 kOe for Bhf and ± 5 % for A.

Analyzing further the Mössbauer parameters of these components, the Fe3+ component acquires an absorption area (A) of 36 % (brown color component) and the Fe2.5+ component of 47 % (green color component). The ratio A(Fe3+)/A(Fe2.5+) = 0.77 is quite different from the nominal 0.5 expected for magnetite Fe3O4, indicating that the corresponding stoichiometry is shifted towards an oxidized version of non-stoichiometric magnetite (Fe3-xO4) for the phase represented by these components. Moreover, the shape of the resonant absorption lines of these components contains an asymmetric broadening with increased spreading towards the inner (regarding the velocity scale) side, or lower hyperfine magnetic fields (Bhf) of the lines, which is characteristic feature for the presence of superparamagnetic relaxation due to the reduced particle sizes of this phase in the sample, in comparison to the narrow and symmetric resonant lines observed for bulk magnetite Fe3O4 [30, 31]. In addition, in the case of magnetite Fe3O4 particles in the nanosized range, there are some features that distinguish the nanodispersed from the bulk crystals. In particular, the contribution from the surface Fe2.5+ ions play a significant role in the case of nanoparticles. This contribution, called the “surface factor” [26, 27, 30], is important and acquires size-dependent characteristics. For example, magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles on the order of 10 nm exhibit TVerway above 300 K and hence no electron hoping of Fe2.5+ ions can be observed in the Mössbauer spectrum. In our case, the observation of Fe2.5+ ions indicates the presence of particles with average size above 10 nm. A third magnetically split component (cyan color component), also with very asymmetrically broadened resonant lines and collapsing Bhf characteristics, as well as a minor quadrupole split component (magenta color component) is required to be included in the fitting model to account for the increased asymmetry of the outer resonant lines and the minor contribution in the center of the spectrum, respectively. The parameters of these components fall in the range of the average values for the corresponding parameters of the A and B site magnetically split components. The features described above reveal a system of magnetite Fe3O4 particles that experience different types of superparamagnetic relaxation effects; the larger in size particles acquire “bulk” characteristics with slow superparamagnetic relaxation, while the smaller one experience faster superparamagnetic relaxation at room temperature.

At this point it should be mentioned that maghemite γ-Fe2O3-which shares a similar XRD pattern with magnetite Fe3O4-presents an entirely different Mössbauer spectrum at room temperature, which is also characterized by two sextets, one for the Fe3+ ions on the tetrahedral A-sites and one for the Fe2.5+ ions on the octahedral B-sites. However, the acquired hyperfine parameters of the two sextets corresponding to the maghemite γ-Fe2O3 phase are IS = +0.23 mm/s, QS = 0.00 mm/s and Bhf = 500 kOe and IS = +0.35 mm/s, QS = 0.00 mm/s and Bhf = 500 kOe, respectively for each sextet. Thus, the Mössbauer hyperfine parameters between maghemite γ-Fe2O3 and magnetite Fe3O4 particles at room temperature differ significantly from each other. Furthermore, at room temperature, magnetite Fe3O4 and maghemite γ-Fe2O3 exhibit well defined magnetic hyperfine splitting (sextets) only for particles with a diameter larger than 15 nm; for smaller ones, low temperatures are needed to slow down the superparamagnetic relaxation of these iron oxide phases [32]. In the present case, the appearance of magnetically split components (sextets) in the 57Fe Mössbauer spectrum confirms the existence of particles with sizes above 15 nm in accordance with the X-ray and AFM results. Magnetite sludge was strongly attracted by Nd-magnet. Quantitative information on the magnetic properties of the sample was unfolded through its magnetization M versus magnetic field H measurement at room temperature. This measurement appears in Figure 6 and reveals, as expected, a material with ferrimagnetic character showing a saturation magnetization of MS = 79.7 emu/g and coercive field of HC = 99 Oe (inset). The typical values of the corresponding parameters for bulk magnetite Fe3O4 are MS = 93 emu/g and HC = 4 Oe, while for magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles the MS value is 85 emu/g and the HC 11 Oe [33, 34].

Figure 6: Hysteresis loop of radiator sludge at room temperature.

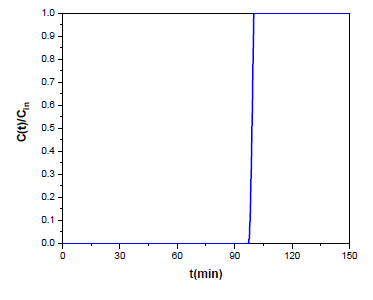

The decreased MS value of the sample is attributed to the shifted stoichiometry and the reduced sizes of the magnetite Fe3O4 particles, as well as the distribution of their sizes, as evidenced by the 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy measurements. Furthermore, the origin of the sample must be considered. Even though radiator sludge is consisted dominantly by magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles, it is important to note that there are also some non-ferrimagnetic residuals that affect the magnetic properties of the sample, such as the non-ferrous elements detected by XRF in Figure 2. In addition, magnetite Fe3O4 is generally prone to surface oxidation towards the formation of a thin γ-Fe2O3 layer that could further decrease the magnetic performance of the sample. On the other hand, the increased coercivity value might be the result of magnetite doping with the non-ferrous elements (e.g., zinc-doped magnetite) [35], which tend to create local structural distortions, such like grain boundaries, twinning or extortions, that induce shape anisotropy through change in the aspect ratio of the crystal structure. The magnetite sludge was following tested in hydrogen sulfide H2S removal as described in the materials and methods section. According to the experimental results shown in Figure 7, the breakthrough time was equal to tb = 97.79 min while the saturation time was equal to ts = 100.02 min. Breakthrough and saturation capacities were calculated using equation 1 at 25 oC and found 90.3 mgH2S/gads (i.e., 2.65 mmolH2S/gads) and 91.4 mgH2S/gads (i.e., 2.68 mmolH2S/gads) respectively. For reasons of comparison, Table 2 indicatively shows the removal capacities of some standard materials from the literature in the temperature range 30-120 oC. Apparently, the performance of magnetite sludge at 25 oC is better than that of synthetic magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles, iron oxides Fe2O3 and iron oxide-modified activated carbon Desorex® in the temperature range 30-120 oC. Considering that magnetite sludge is a raw waste material that has not undergone any further treatment, as well as that sorption experiments have been carried out at 25 oC, the removal capacity of 2.68 mmol H2S per gram of sorbent at room temperature is quite a promising result. Moreover, this value could be further increased by increasing temperature, thus favoring stronger chemical bonding and reaction between the iron oxide sorbent and hydrogen sulfide H2S. As mentioned earlier, magnetite sludge contains residual or additive elements from the steel body of radiator (e.g., Zn, Cu and Cr). These elements can strongly withhold sulfur through the extremely small solubility product (Ksp) constants of the corresponding sulfides. In fact, the Ksp values for ZnS (2.0x10-25), CuS (1x10-36) and Cr2S3 (1x10-20) are orders of magnitude smaller than that of FeS (4.9 x 10-18), thus further assisting hydrogen sulfide H2S retention in the form of highly insoluble metal sulfides. Interestingly, the better catalytic activity of magnetite sludge over synthetic magnetite Fe3O4 (e.g., from Aldrich) was tested by a simple chemical experiment, namely the catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide H2O2. To this aim, 200 mg of magnetite sludge or commercial magnetite Fe3O4 were placed in a test tube and 2 mL 30 % v/v hydrogen peroxide H2O2 (Supelco) were added. It was observed that frothing due to catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide H2O2 into O2 gas was significantly higher in the case of magnetite sludge, thus suggesting its better catalytic activity.

Figure 7: Experimental results for the breakthrough curve of magnetite sludge at 25 oC.

|

Sample |

T |

Breakthrough capac. |

Overall capac. |

SBET |

Ref. |

|

Code |

(°C) |

(mmolH2S/gads) |

(mmolH2S/gads) |

(m2g-1) |

|

|

Fe2O3 |

30 |

0.02 |

- |

5 |

[16] |

|

Fe2O3 |

120 |

0.24 |

- |

5 |

[16] |

|

Fe3O4 |

30 |

0.07 |

- |

26 |

[16] |

|

Fe3O4 |

120 |

1.48 |

- |

26 |

[16] |

|

Desorex K43-BG |

30 |

2.58 |

8.6 |

1005 |

[22] |

|

Desorex K43-Fe |

30 |

0.82 |

1.2 |

952 |

[22] |

|

Desorex K43Na |

30 |

4.58 |

8.2 |

815 |

[22] |

|

Magnetite sludge |

25 |

2.65 |

2.68 |

10 |

[this work] |

Table 2: Breakthrough and overall hydrogen sulfide H2S removal capacities of different materials under various sorption process conditions.

4. Conclusions

Magnetite sludge is an iron oxide waste product formed within radiator body by the reaction of steel metal with circulating hot water. As the sludge builds up over time, it causes a number of technical problems in the operation of the system, such as low heating efficiency and blockage of pipes, leading to system breakdown. Hence, the sludge must be removed from radiator in order to maintain the system; nevertheless, the isolated sludge is often discarded to the environment without any further use. Since magnetite Fe3O4 is an inexpensive yet valuable technological material present in large quantities inside radiator bodies, herein we have acknowledged for the first time that magnetite sludge is an important source of cheap waste that is worth converting to a valuable product. The magnetite sludge isolated from radiator was characterized by XRD, XRF, AFM, 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy and magnetic measurements, providing evidence for the structure and morphology of the iron oxide phase. Following, the performance of magnetite sludge as sorbent for hydrogen sulfide H2S removal was investigated. The sludge exhibited a quite efficient removal capacity of 2.68 mmol H2S per gram of sorbent at room temperature, probably due to the presence of residual or additive elements from the steel body of radiator that might act catalytically in the process. Overall, magnetite sludge appears as an attractive, low cost and efficient sorbent towards hydrogen sulfide H2S removal at 25 oC, thus surpassing synthetic magnetite Fe3O4 nanoparticles in the literature with values of 0.1-1.5 mmol H2S per gram of sorbent at 30-120 °C.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by the project “National Infrastructure in Nanotechnology, Advanced Materials and Micro-/Nanoelectronics” (MIS 5002772) which was implemented under the action “Reinforcement of the Research and Innovation Infrastructure”, funded by the Operational Programme “Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation” (NSRF 2014-2020), and co-financed by Greece and the European Union (European Regional Development Fund). It was also funded by the Greek General Secretary of Research and Technology under the research project “Development and demonstration in pilot plant scale of a novel, efficient, and environmentally friendly process for clean hydrogen and electric power production from biogas” (Eco-Bio-H2-FCs).

References

- Bressan F, Hess RL, Sgarbossa P, et al. Chemistry for audio heritage preservation: a review of analytical techniques for audio magnetic tapes. Heritage 2 (2019): 1551-1587.

- Pfaff G. Iron oxide pigments. Phys Sci Rev 6 (2021): 535-548.

- Theofanidis SA, Galvita VV, Konstantopoulos C, et al. Fe-based nano-materials in catalysis. Materials 11 (2018): 831.

- Scherer C, Neto AMF. Ferrofluids: properties and applications. Braz J Phys 35 (2005): 718-727.

- Laurent S, Forge D, Port M, et al. Magnetic iron oxide nanoparticles: synthesis, stabilization, vectorization, physicochemical characterizations, and biological applications. Chem Rev 108 (2008): 2064-2110.

- Xu P, Zeng GM, Huang DL, et al. Use of iron oxide nanomaterials in wastewater treatment: a review. Sci Total Environ 424 (2012): 1-10.

- Lima MSS, Thives LP, Haritonovs V, et al. Red mud application in construction industry: review of benefits and possibilities. IOP Conf Ser: Mater Sci Eng 251 (2017): 012033.

- Kurtoglu SF, Uzun A. Red mud as an efficient, stable, and cost-free catalyst for COx-free hydrogen production from ammonia. Sci Rep 6 (2016): 32279.

- Du Y, Dai M, Cao J, et al. Fabrication of a low-cost adsorbent supported zero-valent iron by using red mud for removing Pb(II) and Cr(VI) from aqueous solutions. RSC Adv 9 (2019): 33486.

- Joseph CG, Taufiq-Yap YH, Krishnan V, et al. Application of modified red mud in environmentally-benign applications: a review. Environ Eng Res 25 (2020): 795-806.

- Agrawal S, Dhawan N. Evaluation of red mud as a polymetallic source-A review. Miner Eng 171 (2021): 107084.

- Wiheeb AD, Shamsudin IK, Ahmad MA, et al. Present technologies for hydrogen sulfide removal from gaseous mixtures. Rev Chem Eng 29 (2013): 449-470.

- Shah MS, Tsapatsis M, Siepmann JI. Hydrogen sulfide capture: from absorption in polar liquids to oxide, zeolite, and metal-organic framework adsorbents and membranes. Chem Rev 117 (2017): 9755-9803.

- Georgiadis AG, Charisiou ND, Goula MA. Removal of hydrogen sulfide from various industrial gases: a review of the most promising adsorbing materials. Catalysts 10 (2020): 521.

- Huang G, He E, Wang Z, et al. Synthesis and characterization of γ-Fe2O3 for H2S removal at low temperature. Ind Eng Chem Res 54 (2015): 8469-8478.

- Janetaisong P, Lailuck V, Supasitmongkol S. Pelletization of iron oxide based sorbents for hydrogen sulfide removal. Key Eng Mater 751 (2017): 449-454.

- Lincke M, Petasch U, Gaitzsch U, et al. Chemoadsorption for separation of hydrogen sulfide from biogas with iron hydroxide and sulfur recovery. Chem Eng Technol 43 (2020): 1564-1570.

- Cristiano DM, Mohedano RA, Nadaleti WC, et al. H2S adsorption on nanostructured iron oxide at room temperature for biogas purification: application of renewable energy. Renew Energy 154 (2020): 151-160.

- Mrosso R, Machunda R, Pogrebnaya T. Removal of hydrogen sulfide from biogas using a red rock. J Energy 2020 (2020): 2309378.

- Costa C, Cornacchia M, Pagliero M, et al. Hydrogen sulfide adsorption by iron oxides and their polymer composites: a case-study application to biogas purification. Materials 13 (2020): 4725.

- Choudhury A, Lansing S. Adsorption of hydrogen sulfide in biogas using a novel iron-impregnated biochar scrubbing system. J Environ Chem Eng 9 (2021): 104837.

- Castrillon MC, Moura KO, Alves CA, et al. CO2 and H2S removal from CH4-rich streams by adsorption on activated carbons modified with K2CO3, NaOH, or Fe2O3. Energy Fuels 30 (2016): 9596-9604.

- Douvalis AP, Polymeros A, Bakas T. IMSG09: a 57Fe-119Sn Mössbauer spectra computer fitting program with novel interactive user interface. J Phys Conf Ser 217 (2010): 012014.

- Cornell RM, Schwertmann U. The iron oxides: structure, properties, reactions, occurrences and uses. 2nd completely revised and extended edition, Wiley-VCH 2006.

- Cullity BD, Stock SR. Elements of X-Ray diffraction. 3rd edition, Prentice Hall 2001 (664 pages).

- Shipilin MA, Zakharova IN, Shipilin AM, et al. Mössbauer studies of magnetite nanoparticles. J Surf Investig 8 (2014): 557-561.

- Lyubutin IS, Lin CR, Korzhetskiy YV, et al. Mössbauer spectroscopy and magnetic properties of hematite/magnetite nanocomposites. J Appl Phys 106 (2009): 034311.

- Winsett J, Moilanen A, Paudel K, et al. Quantitative determination of magnetite and maghemite in iron oxide nanoparticles using Mössbauer spectroscopy. SN Appl Sci 1 (2019): 1636.

- Cullity BD, Graham CD. Introduction to magnetic materials. 2nd edition, Wiley-IEEE press 2009: 568.

- Dézsi I, Fetzer C, Gombköto Á, et al. Phase transition in nanomagnetite. J Appl Phys 103 (2008): 104312.

- Mørup S, Hansen MF. Superparamagnetic particles. In Handbook of magnetism and advanced magnetic materials. Kronmüller H, Parkin S (Eds.), John Wiley & Sons 4 (2007): 2159-2176.

- Li D, Teoh WY, Selomulya C, et al. Insight into microstructural and magnetic properties of flame-made γ-Fe2O3 J Mater Chem 17 (2007): 4876-4884.

- Ahmadzadeh M, Romero C, McCloy J. Magnetic analysis of commercial hematite, magnetite, and their mixtures. AIP Adv 8 (2018): 056807.

- Özdemir Ö. Coercive force of single crystals of magnetite at low temperatures. Geophys J Int 141 (2000): 351-356.

- Castellanos-Rubio I, Arriortua O, Marcano L, et al. Shaping up Zn-doped magnetite nanoparticles from mono- and bimetallic oleates: the impact of Zn content, Fe vacancies, and morphology on magnetic hyperthermia performance. Chem Mater 33 (2021): 3139-3154.

Impact Factor: * 2.9

Impact Factor: * 2.9 Acceptance Rate: 78.36%

Acceptance Rate: 78.36%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks