Re-establishing the Reality of the Women-only Amazon Societies by Integrating the Evidence from the Historical Record

Peter Brecke*

Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America

Corresponding Author: Peter Brecke, Sam Nunn School of International Affairs, Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, Georgia, United States of America.

Received: 14 August 2024; Accepted: 24 August 2024; Published: 24 October 2024

Article Information

Citation: Peter Brecke. Re-establishing the Reality of the Women-only Amazon Societies by Integrating the Evidence from the Historical Record. Journal of Women’s Health and Development. 7 (2024): 89-103.

DOI: 10.26502/fjwhd.2644-288400125

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The Women-only Amazons were societies where women lived without men on a sustained basis and displayed military prowess. These Amazons were those first described by ancient Greek historians and other authors. Currently, the Women-only Amazons are widely considered to be mythological. This paper and its appendices provide extensive evidence that the Women-only Amazon societies were real. Using internet technologies, this research integrates a vastly expanded sample of documents written about the Women-only Amazons as societies from the ancient authors who were their contemporaries. This research found 78 authors that described where the Amazons lived and when, as well as how. From this unprecedented assemblage of descriptions about the Amazons emerges four related groups of Women-only Amazon societies. Google Earth maps portray where the different Amazon groups lived, and the data show they existed for at least 1700 years. This research finding is relevant to the modern world because descendants of some of the Amazons contributed to the establishment of one of the foundations of modern democracy. This research intends to stimulate and focus archaeological research by identifying and placemarking as precisely as possible the locations of the Women-only Amazons provided by the ancient scholars.

Keywords

<p>Amazons; Women warriors; Women-only societies; Geolocate; Wonder Woman</p>

Article Details

Introduction

The Women-only Amazons were societies where women lived without men on a sustained basis and displayed military prowess. To distinguish them from the many other groups labeled “Amazons,” the Women-only Amazons discussed here were those first described by ancient Greek authors. Remarkably, the Women-only Amazons are now believed to be mythological, rather than ancient societies that existed. Review of links from an internet search using the text “amazon women warriors” at the time of writing this (March 2020) makes that clear. The women-only, Amazon warrior society depicted at the beginning of the Wonder Woman (2017) movie gives us a modern, fanciful depiction of them. Against this mythical status, scholars have sought to demonstrate the reality of the Women-only Amazons for 500 years, so far without success [1]. The two most recent exhaustive attempts to ascertain whether the Women-only Amazons were real arrived at inconclusive outcomes. Blok concluded they did not exist [2]. Mayor concluded they did exist [3]. But she did so by redefining Amazons to include other societies that were Women-only Amazon-like. These Amazon-like societies had large numbers of woman warriors and at least occasionally ruling queens who led the army, but women lived with men. The ancient authors treated these Amazon-like societies as distinct from the Women-only Amazons with these societies possessing their own non-Amazon names, distinct traits, and living in different geographic locations. Examples of these Amazon-like societies described by the ancient authors are the so-called Aethiopian Amazons, the Issedones, Massagetae, Sacae, Zaueces, and some Sauromatae subtribes. This paper focuses on just the Women-only Amazons. What we know about the Amazon-like societies from the ancient authors is beyond the scope of this paper.

This research goes beyond previous efforts and re-establishes the existence of the Women-only Amazons through four major advances. First, this project assembled many more descriptions of the Amazons as societies written by the ancient historians, ethnographers, geographers, and other authors who were their contemporaries. This effort created a compilation of 78 authors’ works, each with one to several observations about the Women-only Amazon societies. The number of both authors and observations is almost triple that found in previous studies. Second, in an attempt to make these observations as concrete as possible, this research identifies and demarcates using Google Earth the locations associated with the Amazons by those authors. Seeing where the Amazons lived and traveled transforms them from a people who are vaguely “out there somewhere” to groups that lived in very specific places at specific times. Third, through the combination of the first two actions, this research identifies four distinct groups of Amazons. This finding was key because it enabled making sense of the varied and sometimes confusing descriptions. Distinguishing between different groups of Amazons was explicitly done by two of the ancient authors, but this work was able to go much further because of the expanded number of descriptions and the geographic visualization of the Amazon groups [4, 5]. And finally, this paper contains in its appendices all of the factual information about the Women-only Amazon societies made by the 78 ancient authors and precise citations for those factual assertions. This will be a valuable research tool as it will save much time and effort for future scholars conducting research on the Women-only Amazons.

Scope of study

There are, to be sure, stories about the Amazons that are mythological. For example, the Amazon origins myth states that Amazons emerged from a liaison between the Greek god Ares (Mars) and Harmonia, a Naiad (female spirit) at the Akmon Grove near the Thermodon (modern-day Terme Cay) River in northern Turkey near the Black Sea coast [6]. According to other stories by Greek authors, Greek heroes such as Achilles, Heracles, or Theseus found the Amazons to be fierce warriors and worthy foes. There is at best limited truth to these stories, and for the purpose of this research they are unimportant. Similarly, numerous stories about Amazon queens and warriors as individuals may be true or contain a kernel of truth, but they prove inadequate as a foundation for re-establishing the reality of the Women-only Amazons. In general, stories about the exploits of individuals, which may be prone to being embellished, need to be viewed with skepticism. This research instead focuses on the descriptions and factual information they contain–observations regarding locations and characteristic behaviors or possessions of the Women-only Amazons as societies–written by the ancient authors. This factual information is both a much larger portion of the descriptions than the stories about exploits and may be more reliable because the authors had no need to exaggerate or mislead regarding things such as that the Amazons wore leather lace-up boots and grew crops. The paper and accompanying appendices integrate, summarize, and document those descriptions and facts. Relevant archaeological evidence is used to augment the descriptions.

To re-establish the existence of the Women-only Amazon societies, the foundational information of who, where, when provided by the ancient authors must be the starting point. If that basic, factual information cannot be established, making a convincing case for their existence is not possible. The locations inhabited or used by the Amazons along with when they were at these locations is thus the core of this research project. Fortunately, the locations of the Amazons is the fact about them that most writers included. This paper presents those locations using Google Earth, with each location determined and “placemarked” as precisely as possible. Geographic visualization of the locations demonstrates that the Amazons lived within limited and clearly defined regions. Additional information augmenting the locations includes migration paths travelled by different Amazon groups, key events they experienced as societies, and approximate dates of certain events. The reality of the Women-only Amazons is of interest beyond establishing that a society now treated as mythological actually existed. Descendants of the Amazons played a role in a much larger story. A group of them, called the Sitones, participated in the establishment of one of the foundations of modern democracy, Things in Northern Europe. Things were (and two still are) local democratic assemblies that met periodically and exercised considerable decision-making power. They were established almost certainly in the 5th century BCE near Uppsala, Sweden and spread from there across much of northern and northwestern Europe to as far as southern Greenland by about 1000 CE. Some continued operating until as recently as 1832 in England and 1907 in Sweden. Describing the history of Things and tracing the connection between the Amazons and Things is far beyond the scope of this paper. However, the Women-only Amazons could not have been the starting point for the Sitones' participation in establishing Things if they were not real, and thus determining that fact instigated this research project.

The argument establishing the Amazons as real begins with a description of the method employed to assemble the data. After that, a description of the most basic finding that four groups of Women-only Amazons existed establishes the organization of the subsequent sections. Third, the paper reviews the limited archaeological evidence supporting the existence of a few of the Amazon groups. Fourth, the paper summarizes what we know about the Amazon societies in terms of how the different Amazon groups lived. After that, the paper describes key elements of each of the groups and presents maps delineating the general regions and specific locations where they lived. The discussion completes the argument. Appendices contain the observations found in the ancient authors’ works.

Method

The methodology of this research project is that of an observational science. Deep-space astronomy can serve as an analogy. Deep-space astronomy typically makes discoveries by using new telescopes with improved capabilities to peer farther out in space or to see nearer objects with greater clarity. The initial observations of a new object or phenomenon usually consist of a small number of fuzzy (or increasingly, pixelated) images. Astronomers then search for more examples to assemble a sample of increasing size that both improves confidence in the reality of the new phenomenon and more observations of the properties of the phenomenon. Executing an observational science emphasizes increasing, hopefully maximizing, the sample size and making the most precise measurements possible of different facets of the phenomenon. All observational scientists acknowledge that there are errors in their measurements; the goal is to minimize the error. To make the case for the existence of a phenomenon to others, an observational science relies on clear, thorough, and accurate documentation of the observations placed into a dataset that is made available. This project generated that documentation for observations about the Women-only Amazons, which are in the appendices. For this project, the observations consist of written descriptions from the earliest examples of the historical record pertaining to the territories where the Women-only Amazons lived. The scientific contribution of this research lies in its application of new(ish) technologies (Google Search, Google Earth, and a multitude of websites) to greatly expand the assembled sample of observations and documenting the information extracted from these observations. This research project has made no attempt to link the research or its findings to other epistemological, paradigmatic, or interpretive approaches such as structuralism, post-modernism, or new historicism. No theory explaining how the Amazons came to be or how their existence and actions affected subsequent events has been articulated. Those tasks are left to others. The goal here has been to assemble, record, document, and summarize the observations so that others have an evidentiary foundation upon which to work.

In terms of process, this research at its core involved finding the location of the cities, towns, temples, shrines, places of battle, or other places the ancient authors associated with the Amazons as inhabitants or visitors. This was made possible with Google Earth. Creating a database of the locations entailed setting Placemarks in Google Earth as close as possible to where each of those places is now believed to have been. Determining these locations involved either finding the modern-day name for that location, a latitude and longitude number pair, or finding mentioned reference points such as mountains or rivers that enabled triangulation of the location. The goal was to set the placemarks within 100 meters of the ancient locations. The conversion from ancient to modern names and finding latitude/longitude pairs was made using Google Search, often in conjunction with Wikipedia, which includes latitude/longitude information in the webpage for many locations. While some question using Wikipedia over concerns about reliability or misinformation, the location of an (often obscure) ancient site is an unlikely target of misinformation, and someone who would go through the effort to specify latitude and longitude is likely to want to get it right. When a precise location could not be determined, I then attempted triangulation based on the textual descriptions. Since the precision of a triangulated location varies with the specificity of the description and the number of reference points, if the triangulation evidence for a particular location was too vague (uncertainty as to whether the site can be located to within one kilometer), the location was not included in the Google Earth data file. Fortunately, there are very few examples of triangulated locations. Less precise descriptions of regions where the Amazons lived were demarcated by colored lines (Paths in Google Earth) serving as approximate boundaries of the Amazon domains. A Google Earth (.kml) data file (Re-establishing the Reality of the Women-only Amazon Societies locations.kml) containing the Placemarks and Paths identified for this research project is included as supplementary data. Placemarks contain the source from which the precise location was obtained. The location data are presented in maps because the visual depiction enables a condensation of the information and a clarity not possible with textual elaboration.

Finding the ancient references with locations entailed going back to the writings of the ancient authors, starting with scholarly English translations, but also the original ancient Greek or Latin texts, to acquire all of the observations they contained and to minimize errors in translations. Translation errors by previous scholars, especially names of tribes but sometimes even numbers, occurred several times. For those texts for which there was not an English, French, or German language edition, translations for this project were done by both individuals conversant in ancient Greek or Latin and Google Translate. As part of this research project's attempt to maximize findings by gathering data from authors not included in standard accounts of the Amazons, the search effort involved examining thousands of documents while following bibliographic and footnote trails back to their beginnings. For example, the fragmentary descriptions of the Amazons found in Mueller and Jacoby were used [7, 8]. There may be authors who were not found and thus included, but there are almost certainly very few of them. To temporally locate the descriptions and thus the Amazons, I conducted a secondary data gathering effort that arrived at the most precise and up-to-date estimates for the date of each author’s relevant publication(s). Doing this helped determine the ranges of dates for when the Amazons were at the different locations. Four authors provided dates for events involving the Amazons. While gathering the different descriptions of the Amazon societies, the research effort assembled and documented in the appendices their locations, characteristics as societies, and events they experienced. Although the works of poets and playwrights are stories mainly for entertainment that should be and are treated with caution regarding historical accuracy, they sometimes contain observable, factual statements about the Amazons such as where they lived or weapons they used. For example, four of the authors described the Amazons using crescent-moon shaped shields. One of these authors, Quintus of Smyrna, wrote an account about the Amazons’ fight against the Greeks during the Trojan War. One can be very skeptical about his account of what happened with the Amazon queen during this battle as it reads like a dramatization. Yet, he stated that the queen’s shield was the shape of a crescent moon with the points facing up (like a rising moon) and that there was half empty space between the points [9]. These details tell us in which orientation the Amazons held these shields and quite precisely the shape of the shields. This type of information was included and is documented. Much more important were the writings and maps of the ancient Greek and Latin geographers, ethnographers, and historians, many of them among the most important scholars of that era (see Appendix B). They treated the Women-only Amazons as real and in the same manner they treated other groups or tribes. Their descriptions thus serve as the core evidence for this research project. For example, as the ancient geographers in their writings moved through geographic space, such as along the coastline of the Black Sea, they described a multitude of societies, stating where they lived and sometimes providing a few facts about them. In a matter-of-fact manner, the ancient scholars located where Amazons lived with considerable specificity and sometimes included details of the Amazons’ lifestyle, day-to-day activities, or weapons. Often these details were mundane, such as the Amazons grew crops, managed pastures, and wore open-toed, lace-up leather boots called buskins [10, 11]. We actually know more about the Amazons than most of the other tribes mentioned by the ancient geographers as many of the other tribes appeared only in lists of the peoples inhabiting a particular region.

In fact, (and a great surprise to me), as one reads the descriptions of the different societies, the Amazons do not stand out as being considered particularly unusual. They were bit players in the books, seldom getting even as much as one page of description of them as societies. Only one of the 78 ancient authors expressed skepticism about their existence, and that likely happened because he did not separate the Amazons into different groups, the third advance mentioned in the introduction [12]. Three ancient authors wrote statements like “said to be the land of the Amazons” or “believed to be Amazons” that in their context referred to specific groups of Amazons that the author was not certain was of the Amazons he already knew about [13-16].

Some readers may be skeptical that these 78 authors are credible. After all, how can we have faith that these men, who had some strange beliefs by our modern standards such as that there were one-eyed people who lived far to the northeast of the Caspian Sea, were not simply making up stuff? First, one needs to look at their scholarship as a whole and not just dwell on some erroneous statements. A thousand years from now, scholars will find some beliefs held by current scholars, perhaps how ecological systems function or how societies successfully bring about technological innovation, to be laughably wrong, even though the works may be solid current scholarship. When one reads the ancient works, the actual primary sources, and the text surrounding the descriptions of the Amazons, one quickly realizes those authors were as capable intellectually as modern scholars and were doing the best they could with the information they had available. If we accept that the authors were not making up stuff, can we nevertheless think that their sources of information were unreliable? To try address that concern, I strived to achieve both a preponderance of evidence and access to that evidence. With 78 authors there are a lot of descriptions, and the variety in them indicates that the authors did not rely on the same sources. They were only rarely making use of Herodotus, for example. Yet with that variety there is also overlap in the descriptions, and the overlap is remarkably consistent. Moreover, all of the evidence is contained in the appendices, and the appendices come in two forms, standard text and spreadsheets that can be analyzed by computer algorithms to confirm the consistency. Some sources the ancient authors used were almost certainly better than other sources they used, yet a conclusion that they all were nonsense is not warranted. To the ancient authors, the Women-only Amazons were just another society. There is no good reason to disbelieve their factual statements about the Amazons as societies simply because they are about the Women-only Amazons. Disbelieving those factual statements would require us to discard the authors’ statements about all of the other societies they described. Given that many of the authors were among the most important scholars of that era, such disbelief is not justified.

This research is an attempt to separate out the factual from the truly mythological in the ancient works. By then integrating the facts across the 78 authors, this research also gives us, for the first time, a comprehensive set of descriptions of the Women-only Amazon societies.

Results

Four groups of Amazons

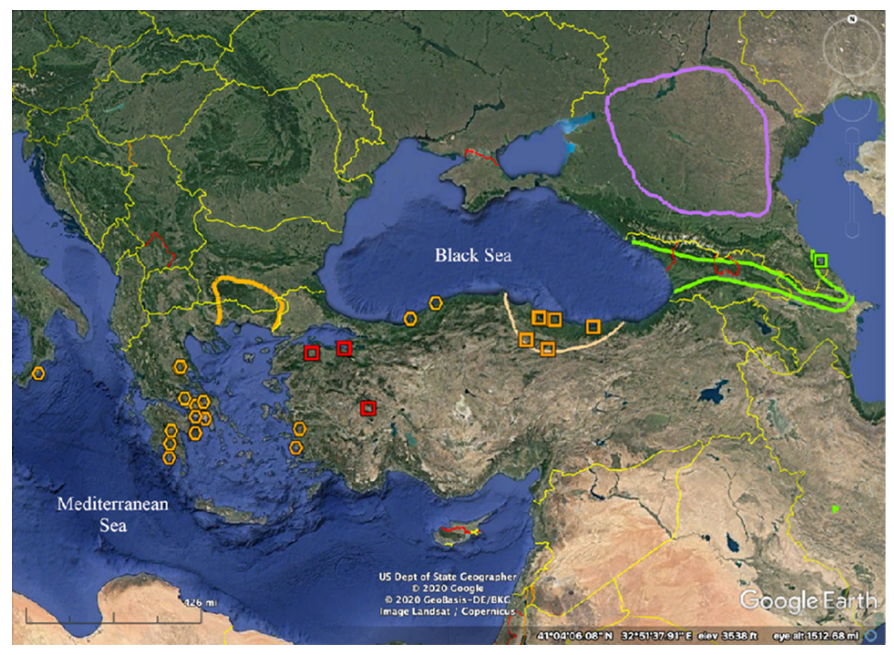

Upon geographically and temporally determining the Amazon locations using all of the 78 authors’ descriptions and compiling their societal characteristics, four distinct groups of Amazons emerged. Figure 1 portrays the groups geographically using color-coding and shape to distinguish them. Where they lived ranges from far southern Italy east and northeast to southwestern Russia. The different Amazon groups are:

- Thermodon Amazons (northern Turkey; orange squares)

- Southern Caucasus Amazons (Georgia, Azerbaijan, and Dagestan, Russia; bright green boundary and one green square)

- Steppe Amazons (southwestern Russia; light purple boundary)

- Other Amazons

- migrants from the Thermodon Amazons depicted with an orange hexagon (Italy, Greece and Turkey) and inside the thick orange line (far south-central Bulgaria and far northeastern Greece).

- three locations whose connection to the Thermodon Amazons but possibly other Amazon-like societies is uncertain (red squares)

Whereas Figure 1 provides a summary depiction of where the different Amazon groups lived, Figure 2 summarizes when the major groups existed in relation to each other and when the migrations from the Thermodon domain occurred.

Archaeological evidence for the Amazons

There is limited archaeological evidence for the existence of the Amazons. A Greek painted terra cotta votive shield (the size and shape of a small plate) from the late 8th century BCE contains the first known depiction of an Amazon [17]. Where it was found, Tiryns, Greece lies less than 53 kilometers (33 miles) from three different Amazon locations. Vases portraying Amazons began appearing in Greece in the 6th century followed by Amazon dolls in the 5th century BCE, and later authors described various temples containing statues and friezes depicting Amazons [18, 19]. Remains of three women’s skeletons armed with swords, daggers, and lances found in 1927 at Semo Awtschala, which is about 11 kilometers (7 miles) north of Tbilisi, Georgia, are likely examples of Southern Caucasus Amazons [20]. One ancient author wrote that the Thermodon Amazons worshipped at a roofless temple, inside of which stood a black stone that was sacred to the Amazons, at the Island of Ares (also known as Aretias or Giresun), which lies just off the south coast of the Black Sea [21]. That stone is almost certainly the Hamza Stone, which is black-colored, about 4 meters in diameter, and stands on the eastern coast of Aretias/Giresun, which is a very small island, 4 hectares (10 acres), and which has the ruins of a roofless temple [22, 23, 24]. The stone rests upon a three-legged stone platform, dates back to at least 2000 BCE, and symbolizes Cybele, an Anatolian mother goddess.

Figure 3 contains a screenshot of a Turkish TV story about the Hamza Stone and a picture of the stone itself [25].

Considerable archaeological evidence has been found demonstrating that women warriors have existed in a variety of places around the world. Davis-Kimball deserves credit for being a pioneer in bringing this evidence to the attention of western scholars and publics [26, 27]. Her and more recent burial finds (Hedenstierna-Jonson 2017; ARSCA 2019; Khudaverdyan et. al. 2021) place women warriors that the authors often call “Amazons” from Sweden to southwestern Russia to Armenia to western Mongolia, a very large swathe of territory [28, 29, 30]. If “Amazon” is equated with women warriors, there is now little question about the existence of “Amazons” in the past. This research accepts that evidence but moves beyond it. This manuscript focuses on the original set of Amazons, the Women-only Amazons first described by the ancient Greek authors. This research intends to stimulate and focus archaeological research by identifying and placemarking as precisely as possible the locations of the Women-only Amazons provided by the ancient scholars.

Characteristics of the Women-only Amazon societies

This section summarizes how the Women-only Amazon societies lived. Each of the Amazon groups received unique descriptions from the ancient authors. Of the 78 authors, 49 described characteristics of these Amazon societies. Three behaviors set the Amazons apart from the other societies described in the ancient texts. First, most of the Amazons lived without men on a regular basis. With respect to the Thermodon, Southern Caucasus, and Steppe Amazons, 11 ancient authors described how they kept their societies going in the absence of men. At Thermodon, they coupled on a temporary basis with men from neighboring tribes, one tribe probably being the Chalybes, and one meeting place in particular being a market town by the Halys (modern-day Kizilirmak) River (shown on Figure 4) [31, 32]. At least some of the Southern Caucasus Amazons consorted with men from neighboring tribes for a two-month period each year. Those near the Caspian Sea met with men from the Gelae and Legae tribes to the south of them [33, 34]. The Amazons returned the sons resulting from these liaisons to their fathers and otherwise lived in their own separate community [35].

At least some of the Steppe Amazons also coupled with men from neighboring tribes (in one case the Gargarians) only during a two-month period in the Spring [36]. The Amazons gave the infant boys to the Gargarians at their border. And while we do not know exactly what was meant, the Steppe Amazons were described as being married (Latin word used was conubia) to a neighboring tribe, the Sauromatae Gynaiko Kratumenoi (an ancient Greek name meaning Sauromatae ruled by women) [37]. The Sauromatae Gynaiko Kratumenoi provided men for the Amazons. Through these actions the Women-only Amazons were able to generate baby girls to keep their societies going. Second, the Amazons (reportedly) abused males through cruel or demeaning acts or the killing of infant boys born from Amazon liaisons with men from neighboring tribes. Of the 41 ancient authors who described characteristics of the Thermodon Amazons, four described them acting demeaning or cruel towards males (though one, Hippocrates, expressed uncertainty), and four more said they killed infant males [38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45]. Three of these eight authors said that intentionally crippled males lived among the Amazons in a subservient role [46, 47, 48]. The Thermodon Amazons stand out from all other Amazons in this regard as these practices were attributed only to this group of Amazons. In contrast, the other 33 authors do not report these anti-male behaviors by the Thermodon Amazons and describe them in a neutral or positive light. One author noted that the Amazons were naturally friendly towards men [49]. In order to reconcile these competing descriptions, there were perhaps one or more periods when these behaviors took place and others when they did not occur. Third, the Amazons either seared/cauterized (five authors), cut off (two authors), or used an unknown method (one author) to minimize the right breast of infant girls, ostensibly so that they could better shoot arrows or throw a lance while riding horseback upon growing up [50-57]. This practice was ascribed to the Thermodon Amazons, the Southern Caucasus Amazons, and the Steppe Amazons. A relatively late (early 3rd century) writer asserted that the name Amazon comes from not being reared at the breast rather than being one-breasted [58]. Adding to the uncertainty about this practice, depictions of Amazons on vases or friezes never showed a missing breast [59]. While we in the 21st century may be skeptical about the possibility that the Amazons did breast removal, we cannot completely reject that possibility. Hippocrates of Kos–the “Father of Western Medicine,” the source of the oath taken by doctors “to first do no harm,” as well as the author mentioned earlier uncertain about Amazon cruelty to men–described the Sauromatae regarding this practice. He described them cauterizing the right breast of baby girls and specified that the Sauromatae did it with a special, red-hot, copper or bronze instrument [60]. The Sauromatae were a large family of tribes sharing the same ethnicity who had women warriors and rulers and a high level of gender equality compared to the societies around them. It is possible that his description became the basis for the claims of breast removal first appearing in writings 350 years later with respect to the Amazons. Given that the Steppe Amazons lived in the same region as several Sauromatae tribes, such a connection is plausible.

So that these descriptions can be readily accessed and compared, they can be found in Appendix A. The descriptions are ordered first by Amazon group and then chronologically, based on when the author wrote the description. Reviewing at least Appendix A is strongly recommended as it provides the reader with an understanding of how much we actually know about the Women-only Amazons from the ancient authors. Appendix B lists the complete set of 78 ancient authors and their relevant works, in chronological order, who geographically located or otherwise described the Amazons as societies. They range chronologically from Homer (850-700 BCE) to Eustathius of Thessalonica (1150-1195). More generally, all appendices can be found in two forms, a Microsoft Excel workbook (.xlsx) with eight worksheets, one for each appendix, and a Portable Document Format (.pdf) human reader-oriented document.

Where the different groups of Amazons lived

The previous section summarizes what we know about the Amazons in terms of characteristics and behaviors as societies. The evidence for their reality becomes more compelling upon examining what we know with respect to where they lived and when. This section covers the four groups of Amazons focusing on the following pieces of information:

- Where they lived in terms of specific locations as well as general regions

- Their origin story if one exists, as well as the story of their demise

- The approximate time they were at those locations when that is possible to estimate

- The linkages between the groups where applicable.

Thermodon Amazons

We know more about the Thermodon Amazons than any other group as 51 ancient authors described or located them. They lived in northern Turkey along the Black Sea coast between Sinope (Sinop) and Trapezous (Trebizond, Trabzon) as seen in Figure 4 [61]. The six locations associated with Amazons that could be geolocated can be seen as orange squares. The Thermodon Amazon domain ranged inland from approximately Sinope southward to Amasya, southeast to Comana (Pontica), and east-northeast to Trapezous. Within that approximate boundary there were other cities or towns (Chadesia and Lykastus depicted on the map; Thermodon, Amazonium, Sotira which could not be geolocated and thus were not depicted), the island worship site with the Hamza Stone (Aretias), and the capital, Themiscyra [62]. Themiscyra was just southwest of modern-day Terme, Turkey near the Thermodon River [63]. The Halys river mentioned earlier where the Amazons met men is also depicted. Appendix C contains the information provided by the ancient authors.

The Thermodon Amazons have an origin story. The story begins when a group of Scythae (Scythas), who lived north of the Caucasus Mountains and east of the Sea of Azov (see Figure 5), migrated to the region around the Thermodon River and Themiscyra [64]. Scythae is a term referring to the large grouping of mainly nomadic peoples who lived on the steppe east and north of the Black Sea and far to the east. Other descriptions support this migration. One of the Thermodon Amazon queens was described as being of the Maeotae [65]. They were a family of tribes who lived in the territory east of the Sea of Azov.

A different author stated that the Thermodon Amazons lived around the Tanais (modern-day Don) River, which flows into the Sea of Azov from the northeast, before migrating to the Thermodon River [66]. A third author said the Thermodon Amazons were descended from the first of all to mount horses [67]. This last statement suggests the Thermodon Amazons descended from peoples of the Yamna (Yamnaya) culture, who were among the first to domesticate horses and who lived in the territory around the Sea of Azov and the Tanais River at the time horses became domesticated [68]. The origin story continues that these Scythae lived around the Thermodon River a long time and periodically raided their neighbors. During one such raid, the Scythae men–who were abusive to their women even by the standards of mid-4th century BCE–were ambushed and defeated by an alliance of neighboring tribes [69, 70]. Out of anger that the men had provoked their neighbors, lost, and thus left them vulnerable, the women decided that they would not allow men among them and would establish a gynecocracy. The women first defended themselves against their neighbors and then took vengeance on them for killing their husbands. Later, “through force of arms” the Thermodon Amazons established peaceful relations with their neighbors and the children-generating practices described earlier [71]. We know that the Thermodon Amazons either were Thracian or were at least related to the Thracians because they spoke the same Thracian dialect and the Amazons’ quivers were filled with feathered Thracian arrows [72, 73, 74]. Figure 6 provides a detailed view of the core domain of the Thermodon Amazons described by the ancient authors. The map contains the locations of the major Amazon settlements in relation to each other and to other geographic reference points such as rivers and a Greek settlement (yellow square).

We know that Chadesia was at the opposite end of the Thermodon (or Themiscyran) plain from Themiscyra, and that Chadesia lay 60 stades (9.4 km or 5.9 miles) from Amisos. Themiscyra was the same distance, 60 stades, from the eastern boundary of the plain. Chadesia sat at the western end of the plain, where rugged terrain comes down to the sea. The Lykastians lived west of the Chadesians, 20 stades (3.2 km or 2 miles) from the later Greek settlement at Amisos [75, 76, 77, 78]. We possess some information as to when the Thermodon Amazons lived in this region. They were the first to possess iron armaments [79]. In order to be the first with iron weapons, the Thermodon Amazons must have existed at least by 1350 BCE when the nearby Hittite Empire had given a hammered iron knife to an Egyptian Pharoah [80]. The Amazons plausibly had early access to iron-making technology because the Chalybes, the tribe that the Greeks believed was the first to mine and work iron and who also were adjacent to the Hittites, lived directly upriver (south of) from the Amazons on the Thermodon River, as well as to the east and west of them [81, 82, 83]. For almost a century these Amazons were a major power in the region [84]. One author asserted that the Thermodon Amazons were at their peak shortly before the Trojan War (1191-1182 BCE according to Eusebius) [85, 86]. These observations imply a timespan for their period as a significant power somewhere in the range 1300-1200 BCE. It was Thermodon Amazons who about 1208 BCE–according to the dating by Eusebius–waged a war against Thebes and much of the rest of mainland Greece, including Athens [87]. The key battle began about September 18 [88]. In 1185 BCE, a band of Thermodon Amazons arrived at Troy to support the Trojans in the Trojan War [89]. It is worth noting that Eusebius’ dates appear to be quite accurate. Modern archaeological research places the destruction of Troy (Troy VIIa) at about 1180 BCE [90].

Three significant events link the Amazons to the Athenian Greeks. While there is minor variation in the details according to different authors, the basic narrative of the three events is that a Greek hero (Heracles or Theseus) went on a mission to raid the Amazons at Themiscyra. With as many as nine ships full of Greek warriors, the raid succeeded, but in the process many Amazons and Greeks died, and a queen was taken back to Athens. Seeking revenge, another queen, who was away during the Greek attack (the Amazons had a diarchic form of government in which two queens alternated ruling at Themiscyra [91]), rebuilt the army over a span of time, probably a number of years, and then with Thracian and Scythae allies launched a major war against Athens and mainland Greece as far as the southern tip of the Peloponnese. But the Amazons ultimately lost. Because of its weakened state following the loss, the Thermodon Amazon domain was attacked by its own neighbors and fell. Many of the surviving Amazons scattered. Finally, the successor to the queen who launched the war against Athens arrived at Troy from the Thermodon region with a band of Amazons, and many of them were killed.

Appendix D and Appendix E contain what 26 of the ancient authors (including Plato) said in considerable detail about the most important (to the Greeks) of those events, the Amazon war against Athens. With respect to their end date, some Amazons continued to live around the Thermodon River until late in the 4th century BCE [92, 93, 94, 95, 96].

Southern Caucasus Amazons

Sixteen of the ancient authors wrote descriptions of these Amazons. This group inhabited the region from western Georgia, around the Phasis (modern-day Rioni) River, eastward to the southern slopes of the Caucasus mountains all the way to the Caspian Sea, now Azerbaijan, and along the coast to the Caspian Gates (modern-day Derbent in Dagestan, Russia) [97- 103]. Figure 7 depicts their approximate domain (within the bright green boundary line) and rivers named in the descriptions. Included is the archaeological site Semo Awtschala discussed earlier. It is possible the domain extended farther south into modern-day Armenia. Appendix F contains the location information depicted in Figure 5 that was provided by the ancient authors.

There is no origin story for these Amazons, but Thermodon Amazons migrated to the Southern Caucasus region no later than about 1207 BCE, after the war against Athens [104]. The armed women’s skeletons found at Semo Awtschala mentioned earlier as archaeological evidence date to about 1000 BCE, making them viable examples of this group of Amazons [105]. More than a millennium later, the Southern Caucasus Amazons in 65 BCE fought as part of Mithridates VI’s alliance against the Roman army under Pompey at the Cyrus (modern-day Kura) and Abas (modern-day Arzana) rivers in eastern Georgia and far northwestern Azerbaijan (Figure 7) [106, 107]. We find them last described living there (and in the present tense) in 100-127 CE [108].

Steppe Amazons

The Steppe Amazons lived north of the Caucasus Mountains across a large expanse of what is now southwestern Russia. They lived among other societies in the region. As shown in Figure 3, they were located as far north as between where the Tanais and Volga rivers come closest to each other south to the Caucasus Mountains [109]. Some authors located Amazons near and west of the Tanais River [110, 111]. And yet others placed them west of the Caspian Sea westward towards the Sea of Azov, and farther south down by the Mermodas (probably modern-day Kuban) River that flows north and then west from the Caucasus Mountains [112, 113, 114]. The purple line delineates an approximate boundary for the Steppe Amazon domain, and the names indicate the areas at which the Steppe Amazons lived according to the ancient authors (and in relation to where the ancient authors placed the Sauromatae Gynaiko Kratumenoi). The specific location information and the sources can be found in Appendix G. There is no origin story for the Steppe Amazons either, but there are two occasions when there was a migration by Thermodon Amazons to the steppe region. The first was after the war against Athens. After the peace treaty between the Athenians and the Amazons was concluded in Jan-Feb 1207 BCE, some remnants of the Thermodon Amazon army moved with their Scythae allies into Scythia (north and northeast of the Black Sea) and made their home among the Scythae [115, 116]. This geographical placement is consistent with where other ancient authors placed these Amazons as seen in Figure 5.

A second migration of Thermodon Amazons to Asia occurred about 1077 BCE [117]. These Amazons migrated with a group of Cimmerians, who lived at Sinope, at the western edge of the Thermodon Amazon domain (Figure 4) [118]. Corroborating this observation, a different author reported Cimmerians living next to Amazons in the steppe region west of the Caspian Sea and north of the Caucasus Mountains [119]. The Amazons appear to have had a positive relationship with the Cimmerians as a fourth author stated that the two groups together attacked their neighbors in Asia in 782 BCE [120].

The Steppe Amazons were described by 17 ancient authors. One author late in the 4th century CE described the Steppe Amazons as current while referring to the Thermodon Amazons as the “Amazons of old” [121]. The Steppe Amazons were the group of Women-only Amazons last reported alive in the historical record. They were described in the present tense as late as 385 CE, and the territory where they lived to the north of the eastern end of the Caucasus mountain chain was called the land of the Amazons in 417 CE [122, 123].

Relationships between groups in the steppe region

Earlier, the Steppe Amazons were described as being “married” to the Sauromatae Gynaiko Kratumenoi, who provided men for procreation. The close relationship between the two societies may have occurred because the Sauromatae Gynaiko Kratumenoi were also descendants of the Thermodon Amazons. The Gynaiko Kratumenoi origin story is that some of the Thermodon Amazons, following the Greek attack at the Thermodon River–in the last third of the 13th century BCE–migrated to the territory east of the Tanais River and the Sea of Azov. This territory is the same region from which the Scythae group initially migrated many years earlier before they became the Thermodon Amazons. Upon their migration back, the Thermodon Amazons merged with men of a Sauromatae subtribe called the Iaxamatae (also called Jaxamatae, Iazamaton), who lived at the mouth of the Tanais, to become a new subtribe called the Sauromatae Gynaiko Kratumenoi [124, 125, 126, 127]. It should be noted that two authors described the Sauromatae, an ethnic group (ethnos), as being almost the same–sharing the same ethnicity–as the Amazons [128, 129]. The relationships between various peoples in the steppe region and the Amazons are depicted in Figure 8. The arrows and dashed line depict the connections articulated by the ancient authors. Interestingly, if one compares across the Iaxamatae, Gynaiko Kratumenoi, and Steppe Amazon societies, one sees a continuum from a society with a high degree of gender equality but mainly male rulers–the norm for Sauromatae tribes–to a society with a high degree of equality but women are the rulers to a society with no men.

Other Amazons

Ancient authors reported several other locations associated with Amazons, mainly in Greece and Turkey, but also in Italy and Bulgaria. These additional locations can be found in Figure 1. In most instances (orange hexagons in southern Italy, southern and central Greece, and northwestern Turkey, and inside the orange line encompassing far south-central Bulgaria and far northeastern Greece), the settlements are outposts from the Thermodon Amazons associated with the war against Athens or the Trojan War. For the three remaining locations (red squares), we know very little, only that at one, Dioklea, the Amazons performed worship ceremonies involving burnt offerings and sacrifices [130]. (Harpocration probably 2nd century). With respect to the timing of these other Amazon locations, we again know only a little. The southern Italian Amazons were founded not long after the Trojan War [131, 132]. By Eusebius’ dating, that would be about 1182-1175 BCE. The locations in Greece, southern Bulgaria, and northwestern Turkey were from after the Amazon-Athens war, thus after 1208 BCE. Appendix H contains what we know about the remaining locations. There are several other locations associated with Amazons by ancient authors along the Aegean Sea coastline of Turkey and three Greek islands in that sea. These locations have not been included in this paper because there is no evidence they were occupied by Women-only Amazons. They instead were associated with migrants from the Women-only Amazon-like Libyan Amazons, who lived with men and are described in a separate paper [133].

Discussion

Integrating and digitizing the written record of the 78 authors who described where and/or how the Amazons lived points firmly to the existence of a set of societies the ancient Greeks called Amazons. These were societies in which women ruled their societies for an extended period and where women lived without men among them. Maximizing the number of observations about the Amazons by using all available sources–-and placing them geographically and temporally–-revealed that there were different Amazon societies. It also enabled delineating which groups were related. By separating the Amazons into the different groups, seeming incongruities in the data–-that made the one ancient author skeptical of their existence–-disappeared because the observations could now be attached to different locations, groups, or times. Going back to the original ancient Greek and Latin texts maximized both the amount and accuracy of the available factual information about the Amazons. This step was important as several translations contained one or more errors, and secondary sources included only some of the observations (those germane to that author’s purpose). Even though many accounts of the Amazons emphasize the stories about the activities of individual Amazon queens or warriors, those stories are only peripheral to the evidence assembled in this project and summarized above. This evidence, which is focused at the level of the Amazon societies and obtained from serious scholars, demonstrates that a social group currently treated as mythological should actually be treated as real and historical in a timespan that ranges from at least the 14th century BCE until about 400 CE–more than 1700 years–in the locations identified above. It is important to note that the appendices contain much more detailed information demonstrating the Women-only Amazons’ existence than has been presented here. The evidence emerged from the descriptions (and the surrounding text to understand their context) and then digitizing, integrating, and geographically visualizing the factual data provided in those descriptions. When one reads the texts of the ancient authors, especially the geographers and ethnographers, it is clear that they attempted to get their facts right. Each of the ancient authors contributed to the evidence, but the act of integrating their observations is the core of this research and what made this finding possible. The goal was to achieve construct validity, the validity that comes from assembling many pieces of evidence such that even though individual pieces of evidence are not conclusive or even completely reliable, the combination of those pieces makes a compelling argument. The quantity of information establishing the existence of the Amazons assembled by this project makes it no longer appropriate to claim the Women-only Amazons are mythological and were not real. If this amount of information were presented about any other social group–for example, if we replaced all instances of “Amazon” in this manuscript with another name such as “Bostonas” and removed the text about killing males (and removing breasts)–there would be no doubt about the Bostonas' existence. The findings of this research should spur efforts by archaeologists to use the precise locations identified in this project to unearth material evidence of the Women-only Amazons that will confirm the historical evidence presented here. Finally, this research demonstrates a new way to use modern internet technologies combined with a scientific approach to assembling and documenting historical data to make discoveries in terms of social groups and social processes at the edge of the historical record that simply were not feasible before.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgements

I thank Julie Simon for editing this manuscript and Baxter Sapp for translation assistance.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Mayor A. Presentation at Emory University, Atlanta, GA on February (2016).

- Blok J. The early Amazons: modern and ancient perspectives on a persistent myth. New York: E. J. Brill (1995).

- Mayor A. The Amazons: lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2014): 31.

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History (Res Gestae) (about 385): Book 22, Chapter 8, Sections 18, 27.

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 3, Chapter 52, Sections 1-3 citing Dionysius Skytobrachion, Argonautai.

- Multiple scholars: Lucillus, Sophocles, Aelius Theon, probably Chares, Irenaeus, Methodius. Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica (about 10-17): Book 2, Section 967 citing Ephoros, Histories (356-330 BCE): Book 9 (Fragment 103); Sections 992, 994 citing Pherekydes, second chapter of a (unknown) book (Fragment 25) (about 450s-420 BCE).

- Mueller CWL. Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum (FHG). Parisiis: A. Firmin Didot (1841-1870). An online version of the work can be found at the Digital Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum (DFHG) (2017).

- Jacoby F. Die Fragmente der Griechischen Historiker I-III (FGrHist). Weidmann: Berlin (1923-1959). An online, English language, and expanded version of this work is Brill's New Jacoby (BNJ), (2006-2021) accessible at https://scholarlyeditions.brill.com/bnjo/.

- Quintus of Smyrna. Posthomerica (Fall of Troy) (probably latter part of 4th century): Book 1, Lines 180-185.

- Parallel Lives, Life of Pompey (about 100-127): Chapter 35, Sections 3-4.

- Geography (7-23): Book 11, Chapter 5, Section 1.

- Geography (7-23): Book 11, Chapter 5, Sections 3-4.

- Appian of Alexandria. Roman History (Historia Romana) (not long before 162): Volume 1 the Foreign Wars, Book 12 the Mithridatic Wars, Chapter 10, Section 69 and Chapter 15, Section 103.

- Arrian of Nicomedia. Circuit of the Black Sea (Periplus Ponti Euxini) (about 131-132): Section 13.

- Arrian of Nicomedia. Anabasis of Alexander (about 130-160): Book 7, Chapter 13.

- Quintus Curtius Rufus. Histories of Alexander the Great (Historiae Alexandri Magni) (about middle to later part of 1st century): Book 6, Chapter 5, Sections 24-32; Book 10, Chapter 4, Section 3.

- Veness R. 2002. Investing the Barbarian? The Dress of Amazons in Athenian Art. in: Llewellyn-Jones L. ed. Women’s Dress in the Ancient Greek World. London: Duckworth (2002): 95-110.

- Mayor A. The Amazons: lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2014): 256.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History (77-79): Book 36, Chapter 4.

- Mayor A. The Amazons: lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2014): 72.

- Apollonius of Rhodes. Argonautica (first half of 3rd century BCE): Book 2, Lines 383-386, 995-1001, 1168-1175.

- Article on the Hamza Stone. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hamza_Stone/ (accessed on 23 March 2016).

- Article on Giresun Island. Available from: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Giresun_Island/ (accessed on 22 December 2013).

- Information about Giresun Island. Available from: http://imturkey.com/en/giresun-island (accessed on May 30, 2022).

- Hamza Tasi Giresun. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=07lh09tOM5U (accessed on May 30, 2022).

- Davis-Kimball J. Warrior Women of the Asian Steppes. Archaeology 50 1 (1997): 44-48.

- Davis-Kimball J. with M Behan. Warrior women: an archaeologist’s search for history’s hidden heroines. New York: Grand Central Publishing (2003).

- Hedenstierna-Jonson C. A Female Viking Warrior Confirmed by Genetics. American Journal of Biological Anthropology 164 4 (2017): 853-860.

- ARSCA (Akson Russian Science Communication Association). Archaeologists found the burial of Scythian Amazon with a head dress on Don EurekaAlert!|AAAS (American Association for the Advancement of Science) news release on December 25, 2019 accessed at https://www.eurekalert.org/news-releases/517672 on June 11, 2022. More information about the research can be found in an article “Don Archaeological Expedition” (in Russian) at https://www.archaeolog.ru/en/expeditions/expeditions-2019/donskaya-arkheologicheskaya-ekspeditsiya accessed on June 11, 2022.

- Khudaverdyan A. et. al. Warrior Burial of the Late Bronze Age and Early Iron Age: the phenomenon of women warriors from the Jrapi cemetery (Shirak Province, Armenia). International Journal of Osteoarchaeology (2021): 1-12.

- Valerius Flaccus. Argonautica (80s): Book 5, Lines 140-141.

- Philostratus of Lemnos. On Heroes (about 213-214 but possibly early 220s): Chapter 6, Section 57.4.

- Parallel Lives, Life of Pompey (about 100-127): Chapter 35, Sections 3-4.

- Geography (7-23): Book 11, Chapter 5, Section 1.

- Quintus Curtius Rufus. Histories of Alexander the Great (Historiae Alexandri Magni) (about middle to later part of 1st century): Book 6, Chapter 5, Section 30.

- Geography (7-23): Book 11, Chapter 5, Section 1.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History (77-79): Book 6, Chapter 7.

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 2, Chapter 45, Section 3.

- Hellanikos of Lesbos. Fragment. (second half of 5th century BCE): Identified as FGrHist 4 F107.

- Hippocrates of Kos. On the Articulations (about 400 BC): Section 53.

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus (Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum Pompei Trogi) (probably 2nd century but possibly later): Book 2, Chapter 4 (The Philippic History written by Pompeius Trogus 30 BCE-10 CE).

- Elegies (about 632-600 BCE): Book 2, Nanno, Fragment 21.

- Paulus Orosius. Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (about 417): Book 1, Chapter 15, Section 3.

- pseudo-Bardaisan (a disciple of Bardaisan named Philip). Law of the Amazons. Book of the Laws of the Countries (2nd or 3rd century): Digital Fragmenta Historicorum Graecorum, Le Pseudo-Bardesane. Le Livre de la loi des contrées.

- Philostratus of Lemnos. On Heroes (about 213-214 but possibly early 220s): Chapter 6, Sections 57.8-57.9.

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 2, Chapter 45, Section 3.

- Hippocrates of Kos. On the Articulations (about 400 BC): Section 53.

- Elegies (about 632-600 BCE): Book 2, Nanno, Fragment 21.

- Parallel Lives, Life of Theseus (about 100-127): Chapter 26, Section 2 citing Bion of Smyrna (late 2nd to early 1st century BCE).

- Arrian of Nicomedia. Anabasis of Alexander (about 130-160): Book 7, Chapter 13.

- Quintus Curtius Rufus. Histories of Alexander the Great (Historiae Alexandri Magni) (about middle to later part of 1st century): Book 6, Chapter 5, Sections 27-28.

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 2, Chapter 45, Section 3.

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus (Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum Pompei Trogi) (probably 2nd century but possibly later): Book 2, Chapter 4 (The Philippic History written by Pompeius Trogus 30 BCE-10 CE).

- Paulus Orosius. Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (about 417): Book 1, Chapter 15, Section 3.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus. The Library and Epitome (Bibliotheca) (about middle of 1st century BCE to very early 1st century CE): Book 2, Chapter 5, Section 9.

- Tetrabiblios (about 127-148): Book 2, Section 3.

- Geography (7-23): Book 11, Chapter 5, Section 1.

- Philostratus of Lemnos. On Heroes (about 213-214 but possibly early 220s): Chapter 6, Sections 57.5-57.6.

- Mayor A. The Amazons: lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2014): 89-90.

- Hippocrates of Kos. On Airs, Waters, and Places (about 400 BCE): Section 17.

- Multiple scholars: Lucillus, Sophocles, Aelius Theon, probably Chares, Irenaeus, Methodius. Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica (about 10-17): Book 2, Section 967 citing Ephoros, Histories (356-330 BCE): Book 9 (Fragment 103); Sections 992, 994 citing Pherekydes, second chapter of a (unknown) book (Fragment 25) (about 450s-420 BCE).

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History (77-79): Book 6, Chapter 4.

- Geography (about 127-148): Book 5, Chapter 6.

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus (Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum Pompei Trogi) (probably 2nd century but possibly later): Book 2, Chapter 4 (The Philippic History written by Pompeius Trogus 30 BCE-10 CE).

- Propertius Sextus. Elegies (about 25-15 BCE): Book 3, Chapter 11, Line 14.

- Histories (about 45-35 BCE). cited by Maurus Servius Honoratus. Commentary on the Aeneid of Virgil (late 4th or early 5th century): Book 11, Section 659.

- Funeral Oration (about 392 BCE): Sections 4-6 (also referred to as 2.4-2.6).

- Librado P, Khan N, Fages A, et al. The origins and spread of domestic horses from the Western Eurasian steppes. Nature 598 (2021): 634–640.

- Multiple scholars: Lucillus, Sophocles, Aelius Theon, probably Chares, Irenaeus, Methodius. Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica (about 10-17): Book 2, Section 967 citing Ephoros, Histories (356-330 BCE): Book 9 (Fragment 103).

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus (Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum Pompei Trogi) (probably 2nd century but possibly later): Book 2, Chapter 4 (The Philippic History written by Pompeius Trogus 30 BCE-10 CE).

- Paulus Orosius. Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (about 417): Book 1, Chapter 15, Section 3.

- Arctinus of Miletus. Aethiopis, (775-741 or possibly the first half of the 7th century BCE): Fragment 1 cited by Eutychios Proclus. Chrestomathia (second half of 2nd century CE): Section 2.

- Multiple scholars: Lucillus, Sophocles, Aelius Theon, probably Chares, Irenaeus, Methodius. Scholia on Apollonius Rhodius’ Argonautica (about 10-17): Book 2, Section 967 citing Ephoros, Histories (356-330 BCE): Book 9 (Fragment 103); Sections 992, 994 citing Pherekydes, second chapter of a (unknown) book (Fragment 25) (about 450s-420 BCE).

- Aeneid (29-19 BCE): Book 5, Lines 311-313.

- Stephanus Byzantinus. Chadisia. Ethnika (early 6th century) citing Hekataios of Miletus, Genealogies (also called Histories, late 6th or early 5th century BCE): Book 2.

- Geography (7-23): Book 12, Chapter 3, Sections 14.

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History (77-79): Book 6, Chapter 4.

- Circuit of the Black Sea (Periplus Ponti Euxini), (in the 5th or more likely 6th century) in Hoffmann S F Guil ed. Periplus ponti Euxini. Anonymi Periplus ponti Euxini, qui Arriano falso adscribitur. Anonymi Periplus ponti Euxini et Maeotidis paludis. Anonymi, Mensura ponti Euxini. Agathemeri Hypotyposes Geographiae. Fragmenta Duo Geographica (1842); 118-119: 151-152.

- Funeral Oration (about 392 BCE): Sections 4-6 (also referred to as 2.4-2.6).

- Coghlan H. Prehistoric iron prior to the dispersion of the Hittite Empire. Man 41 (1941): 80.

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History (Res Gestae) (about 385): Book 22, Chapter 8, Section 21.

- Apollonius of Rhodes. Argonautica (first half of 3rd century BCE): Book 2, Lines 383-386, 995-1001, 1168-1175.

- Pomponius Mela. Description of the World (De situ orbis) (about 43): Book 1, Chapter 19, Sections 9 and 17; Book 3, Chapter 5, Section 4.

- Paulus Orosius. Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (about 417): Book 1, Chapter 16, Section 1.

- Eusebius of Caesarea. Chronicle (about 326): Book 2, Chronological Canons, Part 1 as found in Jerome. Chronicle (about 380).

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 3, Chapter 52, Sections 1-2.

- Eusebius of Caesarea. Chronicle (about 326): Book 2, Chronological Canons, Part 1 as found in Jerome. Chronicle (about 380).

- Parallel Lives, Life of Theseus (about 100-127): Chapter 26, Section 2 citing Bion of Smyrna (late 2nd to early 1st century BCE).

- Eusebius of Caesarea. Chronicle (about 326): Book 2, Chronological Canons, Part 1 as found in Jerome. Chronicle (about 380).

- Jablonka P. Troy. In Cline E ed. The Oxford Handbook of the Bronze Age Aegean Oxford University Press (2010): 849-861.

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus (Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum Pompei Trogi) (probably 2nd century but possibly later): Book 2, Chapter 4 (The Philippic History written by Pompeius Trogus 30 BCE-10 CE).

- Arrian of Nicomedia. Anabasis of Alexander (about 130-160): Book 7, Chapter 13.

- Quintus Curtius Rufus. Histories of Alexander the Great (Historiae Alexandri Magni) (about middle to later part of 1st century): Book 6, Chapter 5, Sections 24-32; Book 10, Chapter 4, Section 3.

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 17, Chapter 77, Sections 1-3.

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus (Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum Pompei Trogi) (probably 2nd century but possibly later): Book 2, Chapter 4 (The Philippic History written by Pompeius Trogus 30 BCE-10 CE).

- Geography (7-23): Book 11, Chapter 5, Section 4.

- Prometheus Bound (480s-430 BCE): Lines 415-419.

- Appian of Alexandria. Roman History (Historia Romana) (not long before 162): Volume 1 the Foreign Wars, Book 12 the Mithridatic Wars, Chapter 15, Section 103.

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 17, Chapter 77, Sections 1-3.

- Epitome of the Philippic History of Pompeius Trogus (Epitoma Historiarum Philippicarum Pompei Trogi) (probably 2nd century but possibly later): Book 2, Chapter 4; Book 12, Chapter 3 (The Philippic History written by Pompeius Trogus 30 BCE-10 CE).

- Paulus Orosius. Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (about 417): Book 1, Chapter 2, Sections 49-50.

- Philostratus of Lemnos. On Heroes (about 213-214 but possibly early 220s): Chapter 6, Section 57.3.

- Parallel Lives, Life of Pompey (about 100-127): Chapter 35, Sections 3-4.

- Funeral Speech (338 BCE): Section 8 (also referred to as 60 8).

- Mayor A. The Amazons: lives and legends of warrior women across the ancient world. Princeton: Princeton University Press (2014): 72.

- Appian of Alexandria. Roman History (Historia Romana) (not long before 162): Volume 1 the Foreign Wars, Book 12 the Mithridatic Wars, Chapter 15, Section 103.

- Parallel Lives, Life of Pompey (about 100-127): Chapter 35, Sections 3-4.

- Parallel Lives, Life of Pompey (about 100-127): Chapter 35, Sections 3-4.

- Geography (about 127-148): Book 5, Chapter 8.

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History (Res Gestae) (about 385): Book 22, Chapter 8, Section 27.

- The Origins and Deeds of the Goths (about 551): Chapter 5, Section 42.

- Paulus Orosius. Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (about 417): Book 1, Chapter 2, Sections 49-50).

- Pliny the Elder. Natural History (77-79): Book 6, Chapter 14 (13 in one translation), Section 35.

- Geography (7-23): Book 11, Chapter 5, Section 2.

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 4, Chapter 28, Sections 3-4.

- Parallel Lives, Life of Theseus (about 100-127): Chapter 26, Section 2 citing Bion of Smyrna (late 2nd to early 1st century BCE).

- Eusebius of Caesarea. Chronicle (about 326): Book 2, Chronological Canons, Part 1 as found in Jerome. Chronicle (about 380).

- The Histories (450s-425 BCE): Book 4, Section 12.

- Gaius Julius Solinus. The Wonders of the World (De mirabilibus mundi) (also Polyhistor) (early to mid 3rd century): Chapter 17, Section 3.

- Paulus Orosius. Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (about 417): Book 1, Chapter 21, Sections 1-2).

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History (Res Gestae) (about 385): Book 22, Chapter 8, Section 18.

- Ammianus Marcellinus. Roman History (Res Gestae) (about 385): Book 22, Chapter 8, Section 27.

- Paulus Orosius. Seven Books of History Against the Pagans (about 417): Book 1, Chapter 2, Sections 49-50.

- Dionysius Periegetes. Periegesis (27 BCE-20 CE): Lines 652-660.

- The Histories (450s-425 BCE): Book 4, Sections 110-117.

- Pomponius Mela. Description of the World (De situ orbis) (about 43): Book 1, Chapter 19, Section 18 (alternatively Book 1, Sections 114).

- Pseudo-Skymnos. The Periodos to Nicomedes (about 144-100 BCE): Lines 875-884. (Identified as FGrHist 2048, Fragment 16; also accessible as Anonymous. Circuit of the Black Sea (Periplus Ponti Euxini): Section 45 identified as FGrHist 2037, Fragment 74.)

- Pomponius Mela. Description of the World (De situ orbis) (about 43): Book 3, Chapter 5, Section 4 (alternatively Book 3, Sections 39-40).

- Stephanus Byzantinus. Amazoneion. Ethnika (early 6th century) citing Ephoros (probably Histories, 356-330 BCE).

- Valerius Harpocration. Lexicon of the Ten Orators (probably 2nd century BCE): Amazoneion.

- Alexandra (also called Cassandra) (mid 3rd century BCE): Book 3, Sections 992-1007.

- Tzetzes I, Tzetzes J. Scholia on Lycophron (1140-1180): Sections 995-996.

- Diodorus Siculus. The Library of History (Bibliotheca Historica) (60-30 BCE): Book 3, Chapter 55, Sections 5-8 citing Dionysius Skytobrachion (probably between 323-250 BCE).

Appendices Link

https://www.fortunejournals.com/supply/AppendicesJWHD11358.pdf

Impact Factor: * 3.4

Impact Factor: * 3.4 Acceptance Rate: 78.89%

Acceptance Rate: 78.89%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks