Intestinal Tumor Mast Cells in a Pomeranian Dog - Case Report

Alfredo Klesse Neto1, Paolo Ruggero Errante2*

1Student of the Veterinary Medicine Course. Clínica Veterinária Bichos de Sabará, Av. Nossa Sra. do Sabará, 3544 - Vila Emir, São Paulo – SP, Brazil

2Teacher of the Veterinary Medicine Course. Faculdades Integradas Campos Salles, São Paulo, Brazil

*Corresponding Authors: Paolo Ruggero Errante, Teacher of the Veterinary Medicine Course. Faculdades Integradas Campos Salles, São Paulo, Brazil.

Received: 10 November 2025; Accepted: 27 November 2025; Published: 05 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Alfredo Klesse Neto, Paolo Ruggero Errante. Intestinal Tumor Mast Cells in a Pomeranian Dog - Case Report. International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences. 15 (2025): 157-161.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Mast cells are hematopoietic cells distributed in connective tissue, primarily in organs that have primary contact with external antigens. Mast cell proliferative disorders include mastocytoma, which is most commonly seen in dogs in the cutaneous or subcutaneous tissue. Canine intestinal mastocytoma is a rare malignant neoplasm in small animal veterinary practice, and its diagnosis involves a combination of history, clinical examination, imaging, cytology, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry. The recommended treatment involves surgical resection of the tumor mass through enterectomy with enteroanastomosis with wide margins. The prognosis for animals affected by the disease is considered poor regardless of the degree of histological dedifferentiation. In this case report, we describe a seven-year-old male Pomeranian dog diagnosed with intestinal mastocytoma after histopathology and immunohistochemistry for KIT.

Keywords

Dogs; Gastrointestinal tract; Immunohistochemistry; Mast cell tumor; KIT

Dogs articles; Gastrointestinal tract articles; Immunohistochemistry articles; Mast cell tumor articles; KIT articles

Article Details

1. Introduction

Mast cells are pleomorphic cells with spherical, spindle-shaped, or stellate morphology that have round nuclei and cytoplasmic granules. Mast cells originate from hematopoietic cells that migrate to peripheral tissues and, through the local action of cytokines, undergo differentiation into mature mast cells [1,2].

Mast cells are present in various interfaces between the body and the environment, such as the skin and mucosal surfaces of the lungs, gastric mucosa, and perivascular region. Their presence is reduced in parenchymal organs such as the heart, brain, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, and genitourinary tract [3].

Mast cells have cytoplasmic granules that contain a series of inflammatory chemical mediators such as histamine and tryptase, capable of inducing acute symptoms such as urticaria, angioedema, bronchoconstriction, diarrhea, vomiting, hypotension, cardiovascular collapse and death within minutes, depending on the degree of release of these chemical mediators. Mast cells are involved in different tissue responses such as allergic processes, angiogenesis, wound healing, bone remodeling and neoplasms [4-8].

Mast cell tumors are neoplastic proliferations of mast cells [3], and some breeds are described as having a higher frequency of mast cell tumors, such as Boxer, English Bulldog, Boston Terrier, Bull Mastiff, Labrador Retriever, Golden Retriever, Sharpei, Weimaraner, Schnauzer and Beagle [9-12].

Unlike mast cell tumors in dogs, which are primarily cutaneous or subcutaneous in nature [13], the mast cell tumors in cats can occur in three distinct forms [14]. These forms include cutaneous mastocytoma, intestinal mastocytoma, and mastocytoma of the hematopoietic system, which includes involvement of the spleen, liver, and bone marrow, and intestinal and splenic mastocytoma can be grouped as visceral mastocytoma [15]. The most frequent anatomical locations of visceral masses include the spleen and intestine [14,16]. Intestinal mastocytoma is a rarely described malignant neoplasm in dogs in small animal veterinary clinics, and usually involves the small intestine, followed by the ileocecocolic junction and large intestine. The presence of a tumor at the ileocecocolic junction is associated with a worse prognosis and shorter survival time [17].

Visceral mast cell tumors, although rare, are more commonly reported in cats than in dogs; the dogs affected are usually purebred miniature dogs, such as Maltese or Pomeranians [18,19], although a case of intestinal mastocytoma has been described in a Golden Retriever dog [20].

Clinical signs associated with gastrointestinal involvement include anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, and eventual weight loss. Paraneoplastic syndrome may be present along with these symptoms [18-22].

Most animals with intestinal mast cell tumors are taken to the veterinary hospital by their owner due to a history of vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, prostration, distension and abdominal pain. Only one of these symptoms or a combination of them may occur [22]. Diarrhea, with or without hematochezia, is commonly observed, and may be accompanied by fever [19].

2. Case Report

In August 2025, a 7-year-old male Pomeranian dog, neutered, immunized and dewormed, was attended. The tutor reported that the dog had been having sporadic episodes of diarrhea containing blood for 30 days. On the day of the consultation, the tutor stated that the animal had normorexia, normodpsia, normouria, and normoquesia.

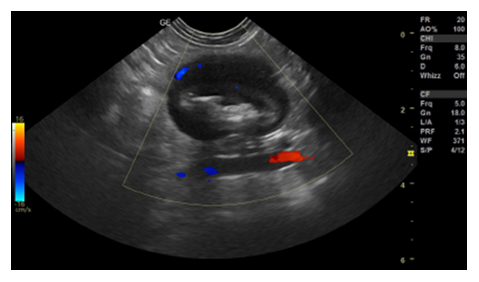

After the clinical examination, a complete blood count, serum biochemistry, urinalysis, abdominal ultrasound and electrocardiogram were requested. The blood count, as well as serum biochemistry tests, showed values within the normal range for the species. Abdominal ultrasound identified the presence of a mass in the left mesogastric region in the jejunal segment that was not causing luminal obstruction (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Abdominal ultrasound. Presence of a focal area with a segment measuring approximately 3.17 cm × 2.31 cm in the jejunum, without lumen obstruction, wall measuring approximately 1.05 cm, presenting an evident muscular layer in the ventral portion, filled with food and gaseous content with discreet vascularization on Doppler.

Due to this ultrasound finding, exploratory celiotomy was performed to remove the intestinal mass (Figure 2) by performing enterectomy with end-to-end enteroanastomosis.

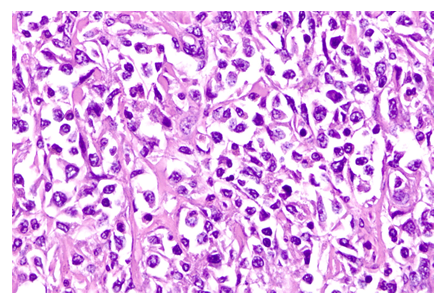

Histopathology of the material obtained by surgical resection was then performed, revealing the presence of pleomorphic, polygonal to fusiform cells, arranged in small cords and bundles interspersed with abundant collagen stroma, containing large, elongated nuclei and evident nucleoli, suggesting mastocytoma (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Histopathological analysis. Presence of pleomorphic, polygonal to spindle-shaped cells, arranged in small cords and bundles interspersed with abundant collagen stroma. The cells have indistinct cell boundaries and little amphophilic cytoplasm. The nuclei are large, elongated, and vesicular, with prominent nucleoli. Anisocytosis and anisokaryosis are evident. Hematoxylin/eosin staining. 100X objective.

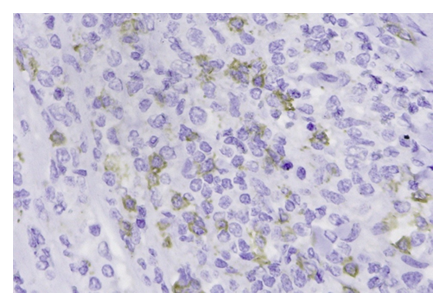

For confirmation, immunohistochemistry was performed using monoclonal antibodies anti-CD3 (T lymphocyte marker), anti-CD20 (B lymphocyte marker), anti-MUM1 (multiple myeloma oncogene, used as a marker for Hodgkin's lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, multiple myeloma and malignant melanoma) and anti-KIT (CD117) (tyrosine kinase receptor marker associated with leukemia, mastocytoma and gastrointestinal stromal tumors).

Immunohistochemical analysis revealed membrane expression of KIT (CD117), with minimal or absent cytoplasmic staining, a finding compatible with the diagnosis of visceral (intestinal) mastocytoma (Figure 4).

3. Discussion

Although canine mastocytoma is most often described as a cutaneous and/or subcutaneous mass, some cases of the visceral form have been described [21-23].

Clinical signs described in gastrointestinal involvement include anorexia, vomiting, diarrhea, and weight loss. Most animals with intestinal mast cell tumors are brought to the small animal veterinary clinic by their tutors with a history of vomiting, diarrhea, anorexia, weight loss, prostration, distension, and abdominal pain. Animals may present with just one of the symptoms or a combination of them. However, diarrhea, with or without hematochezia, is commonly observed, and occasionally accompanied by fever [18-22]. The dog in this report was taken to a clinical consultation due to melena.

In some cases, especially in cats [24], physical examination reveals a single, palpable abdominal mass, accompanied by abdominal distension and pain. The mesenteric lymph nodes may also be enlarged, and hepatomegaly may occur concomitantly [17], facts not observed in the dog in this report.

Intestinal mast cell tumors may be single or multiple and most frequently involve the small intestine, followed by the ileocecocolic junction and large intestine. The presence of the tumor at the ileocecocolic junction is related to a worse prognosis and shorter survival time, with colon involvement being substantially less reported [17-19]. In this report, the mass was found in the left mesogastric region in the jejunal segment.

Diagnostic methods used to identify intestinal mastocytoma include complete blood count, serum biochemical profile, coagulation tests, and imaging tests such as abdominal ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, or computed tomography, with subsequent analysis of the suspected tissue through fine needle aspiration biopsy followed by cytological analysis, histopathology, and immunohistochemistry [25-28].

In this case report, through the use of an imaging exam (abdominal ultrasound), it was possible to identify the presence of a mass located in a segment of the jejunal wall. On abdominal ultrasound, when there is gastrointestinal involvement by mastocytoma, there is thickening of the ileocecocolic junction or colon, accompanied by loss of definition of the edges of the intestinal wall, and the tumoral intestinal masses appear with a hypoechoic, non-circumferential appearance and with eccentric thickening of the wall [28].

Since the use of fine needle aspiration cytology is limited in intestinal tumors, as the cells present little exfoliation and the sample collected is scarce [29], exploratory celiotomy followed by removal of mass for histopathological analysis was preferred.

The treatment of choice for intestinal tumors consists of enterectomy, with resection of the tumor mass and intestinal anastomosis, with it being extremely important to create radical surgical margins of approximately five to ten centimeters on each side of the normal intestine [30,31].

Performing a biopsy, by exploratory celiotomy, is the method of choice for obtaining a definitive diagnosis, with the advantage of evaluating other organs for the presence of metastases or involved lymph nodes, and for differentiating other round cell neoplasms, such as plasmacytoma, lymphoma, histiocytoma and melanoma [32].

Histopathological evaluation of surgical biopsy of the mass is necessary, both for identification and for confirmation or ruling out the suspicion of neoplasia; to differentiate benign from malignant neoplasms and to determine the treatment modality to be applied and associated prognosis [33].

In situations where routine staining does not reveal cytoplasmic granules, Giemsa and toluidine blue stains can be used. However, in more undifferentiated neoplasms, the granules may appear orthochromatic, even after staining with toluidine blue, which is why we did not use this staining method [34].

There are two cytological phenotypes of mast cells: connective tissue cells, which are present in the skin and organs of the peritoneal cavity; and mucosal cells, which are present in the lungs and mucosa of gastrointestinal tract [34]. Mucosal mast cells have a cytoplasm poor in metachromatic granules and may be weakly stained in immunohistochemistry with KIT, requiring tryptase staining to make the diagnosis [19].

Immunohistochemistry is essential to determine the expression of the KIT protein in normal and neoplastic mast cells of dogs and cats, with KIT expression described in well-differentiated mastocytomas in dogs and cats [35].

The KIT is a type III tyrosine kinase receptor encoded by the c-KIT proto-oncogene expressed on the membrane of mast cells and mast cell precursor cells, which acts in the regulation of survival, differentiation and proliferation of normal and neoplastic mast cells [36].

The immunohistochemical staining pattern of KIT involves three types of patterns: membrane expression, with minimal or no cytoplasmic staining; predominantly focal cytoplasmic positivity; and predominantly diffuse cytoplasmic positivity [16].

In our case report, the histopathology result was suggestive of intestinal mastocytoma, which was confirmed through an immunohistochemical technique using the KIT marker.

Animals with intestinal mastocytoma have a poor prognosis regardless of histopathological grading [19]. Animals with mastocytoma, which have mutations in the configuration of membrane protein KIT, generally have a better prognosis than animals in which the tumor does not have alterations in this membrane protein. One of the reasons is the possibility of using tyrosine kinase inhibitor drugs, alone or in combination with other chemotherapeutics in cancer treatment [37-39].

4. Conclusion

Intestinal mast cell tumors in dogs are poorly described and documented in small animal veterinary practice, making it important that they be reported and presented to the scientific community in order to improve diagnostic, treatment, and prognostic strategies.

References

- Pahima HT, Dwyer DF. Update on mast cell biology. J Allergy Clin Immunol 155 (2025): 1115-1123.

- Li NS, Yeh YW, Li L, et al. Mast cells: key players in host defense against infection. Scand J Immunol 102 (2025): e70046.

- Misdorp W. Mast cells and canine mast cell tumours: a review. Vet Q 26 (2004): 156-169.

- Cho WK, Mittal SK, Elbasiony E, et al. Activation of ocular surface mast cells promotes corneal neovascularization. Ocul Surf 18 (2020): 857-864.

- Bacci S. Fine regulation during wound healing by mast cells: a physiological role not yet clarified. Int J Mol Sci 23 (2022): 1-11.

- Ramirez-Gracia Luna JL, Rangel-Berridi K, Olasubulumi OO, et al. Enhanced bone remodeling after fracture priming. Calcif Tissue Int 110 (2022): 349-366.

- Schcolnik-Cabrera A, Morales L, Perez R, et al. Epigenetic reprogramming of mast and cancer cells modifies tumor-promoting cytokine networks. Med Oncol 42 (2025): 371.

- Zhang J, Xie X, Ma R, et al. The role of mast cells in allergic rhinitis. Peer J 13 (2025): e19734.

- Giantin M, Aresu L, Aricò A, et al. Evaluation of tyrosine-kinase receptor c-KIT mutations, mRNA and protein expression in canine leukemia. Vet Immunol Immunopathol 152 (2013): 325-332.

- Warland J, Dobson J. Breed predispositions in canine mast cell tumour: a single centre experience in the United Kingdom. Vet J 197 (2013): 496-498.

- Fonseca-Alves CE, Bento DD, Torres-Neto R, et al. Ki67/KIT double immunohistochemical staining in cutaneous mast cell tumors from Boxer dogs. Res Vet Sci 102 (2015): 122-126.

- Smiech A, Łopuszyński W, Ślaska B, et al. Occurrence and distribution of canine cutaneous mast cell tumor characteristics among predisposed breeds. J Vet Res 63 (2019): 141-148.

- Wyatt EK, Affolter V, Borio S, et al. Mastocytosis in the skin in dogs: a multicentric case series. Vet Comp Oncol 22 (2024): 136-148.

- Melville K, Smith KC, Dobromylskyj MJ. Feline cutaneous mast cell tumours: a UK-based study comparing signalment and histological features with long-term outcomes. J Feline Med Surg 17 (2015): 486-493.

- Hohenhaus AE, Hudak D, Donovan TA, et al. Standardized classification of synchronous gastrointestinal small cell lymphoma and gastrointestinal mast cell tumors in 15 cats. J Feline Med Surg 27 (2025): 1-9.

- Sabattini S, Giantin M, Barbanera A, et al. Feline intestinal mast cell tumors: clinicopathological characterization and KIT mutation analysis. J Feline Med Surg 18 (2016): 280-289.

- Patnaik A, Twedt DC, Marretta SM. Intestinal mast cell tumour in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 21 (1980): 207-212.

- Takahashi T, Kadosawa T, Nagase M, et al. Visceral mast cell tumors in dogs: 10 cases (1982–1997). J Am Vet Med Assoc 216 (2000): 222-226.

- Ozaki K, Yamagami T, Nomura K, et al. Mast cell tumors of the gastrointestinal tract in 39 dogs. Vet Pathol 39 (2002): 557-564.

- Iwata N, Ochiai K, Kadosawa T, et al. Canine extracutaneous mast-cell tumors consisting of connective tissue mast cells. J Comp Pathol 123 (2000): 306-310.

- Baldi A, Colloca E, Spugnini EP. Lomustine for the treatment of gastrointestinal mast cell tumour in a dog. J Small Anim Pract 47 (2006): 465-467.

- Kobayashi M, Sugisaki O, Ishii N, et al. Canine intestinal mast cell tumor with c-kit exon 8 mutation responsive to imatinib therapy. Vet J 193 (2012): 264-267.

- Minnoye S, De Vos S, Beck S, et al. Histopathological features of subcutaneous and cutaneous mast cell tumors in dogs. Acta Vet Scand 66 (2024): 1-10.

- Henry C, Herrera C. Mast cell tumors in cats: clinical update and possible new treatment avenues. J Feline Med Surg 15 (2013): 41-47.

- Sato AF, Solano M. Ultrasonographic findings in abdominal mast cell disease: a retrospective study of 19 patients. Vet Radiol Ultrasound 45 (2004): 51-57.

- Lorigados CAB, Matera JM, Coppi AA, et al. Computed tomography of mast cell tumors in dogs: assessment before and after chemotherapy. Pesqui Vet Bras 33 (2013): 1349-1356.

- Willmann M, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Marconato L, et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria and classification of canine mast cell neoplasms: a consensus proposal. Front Vet Sci 8 (2021): 1-10.

- Nam C, Park N, Shin M, et al. Sonographic and computed tomographic features of intestinal mast cell tumors mimicking alimentary lymphoma in two dogs. Can Vet J 65 (2024): 17-24.

- Willard MD. Alimentary neoplasia in geriatric dogs and cats. Vet Clin North Am Small Anim Pract 42 (2012): 693-706.

- Thomsen BJ, Ulfelder EH. A case of colonic–colonic intussusception in a dog secondary to lymphoma treated with colonic resection and anastomosis. Can Vet J 63 (2022): 957-961.

- Dooley E, Stalker M, Jensen M, et al. Colonic gastrointestinal stromal tumor presenting with colocolonic intussusception: a rare case report. Can Vet J 65 (2024): 25-28.

- García-Reynoso IC, Flores-Dueñas CA, Castro-Del Campo N, et al. Risk factors for the occurrence of cutaneous neoplasms in dogs: a retrospective study by cytology reports, 2019–2021. Animals (Basel) 15 (2025): 1-15.

- De La Mora Valle A, Gómez DG, Muñoz ET, et al. Retrospective study of malignant cutaneous tumors in dog populations in Northwest Mexico from 2019 to 2021. Animals (Basel) 15 (2025): 1-12.

- Blackwood L, Murphy S, Buracco P, et al. European consensus document on mast cell tumors in dogs and cats. Vet Comp Oncol 10 (2012): e1-e29.

- Kumagai K, Uchida K, Miyamoto T, et al. Three cases of canine gastrointestinal stromal tumors with multiple differentiations and c-kit expression. J Vet Med Sci 65 (2003): 1119-1122.

- Webster JD, Yuzbasiyan-Gurkan V, Kaneene JB, et al. The role of c-KIT in tumorigenesis: evaluation in canine cutaneous mast cell tumors. Neoplasia 8 (2006): 104-111.

- Olsen JA, Thomson M, O'Connell K, et al. Combination vinblastine, prednisolone and toceranib phosphate for treatment of grade II and III mast cell tumors in dogs. Vet Med Sci 4 (2018): 237-251.

- Frezoulis P, Harper A. The role of toceranib phosphate in dogs with non-mast cell neoplasia: a systematic review. Vet Comp Oncol 20 (2022): 362-371.

- Lai YY, Dos Santos Horta R, Valenti P, et al. Retrospective safety evaluation of combined chlorambucil and toceranib for the treatment of different solid tumors in dogs. Animals (Basel) 14 (2024): 1-14.

Impact Factor: * 4.1

Impact Factor: * 4.1 Acceptance Rate: 75.32%

Acceptance Rate: 75.32%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks