A Prospective Pilot Study Evaluating the Effect of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Health-Related Quality of Life in Chronic Heart Failure at Laquintinie Hospital, Cameroon

Djibrilla Siddikatou1*, Marie Solange Ndom Ebongue1, Hermann Tsague Kengni2, Mouliom Sidick1, Valérie Ndobo2, Menoue Christele3, Edgar Mandeng Ma Linwa4, Raissa Kamgang Tchounja5, Chris Nadège Nganou-Gnindjio2, Elysée Claude Bika Lele1, Félicité Kamdem1

1Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Douala, Douala, Cameroon

2Faculty of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, University of Yaounde I, Yaounde, Cameroon

3Cardiac prevention foundation, Douala, Cameroon

4Faculty of Heath Sciences, University of Buea, Buea, Cameroon

5Cardiology unit, Internal medicine department, Hopital Laquintinie Douala, Douala, Cameroon

*Corresponding author: Siddikatou Djibrilla, Faculty of Medicine and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Douala, Douala, Cameroon.

Received: 11 December 2025; Accepted: 29 December 2025; Published: 31 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Djibrilla S, Marie Solange NE, Hermann TK, Sidick M, Valérie N, Christele M, Edgar MML, Raissa KT, Chris Nadège N-G, Elysée Claude BL, Félicité K. A Prospective Pilot Study Evaluating the Effect of Cardiac Rehabilitation on Health- Related Quality of Life in Chronic Heart Failure at Laquintinie Hospital, Cameroon. Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine. 9 (2025): 512-518.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

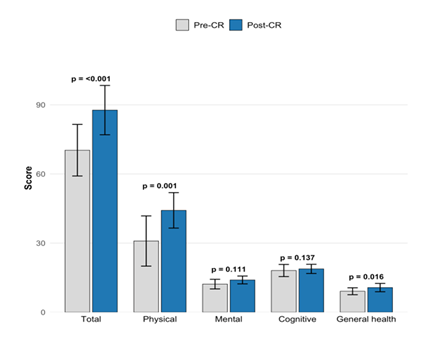

Background: Heart failure (HF) significantly impairs health-related quality of life (HRQoL). The Chronic Heart Failure Health-Related Quality of Life Questionnaire (CHFQOLQ-20) assesses physical, cognitive, general health, and mental domains. Although cardiac rehabilitation (CR) is guideline-recommended, its efficacy in improving HRQoL in sub-Saharan African settings remains poorly documented. Methods: HF patients (NYHA I–III) at Laquintinie Hospital, Douala, completed at least 10 CR sessions. HRQoL was assessed using the CHFQOLQ-20 before and after the CR program. Self-confidence was measured via a 5-point Likert scale. Data was normally distributed and total and domain HRQoL scores were compared with paired t-tests, internal consistency via Cronbach’s alpha. NYHA and self-confidence transitions were analysed using McNemar test. Results: Ten patients were included. Mean total CHFQOLQ-20 score increased from 70.3 ± 11.2 to 87.7 ± 10.7 post-CR (p<0.001). All domains improved significantly: physical function (+13.3, 95% CI: 9.1–17.5, p<0.001), general health (+1.6, p=0.002), except cognitive function (p=0.137) and mental health (p=0.111) domains. Cronbach’s alpha confirmed excellent reliability (pre-CR: 0.83; post-CR: 0.93). NYHA class improved in 40% (McNemar, p=0.344) and self-confidence improved markedly: 60% of patients transitioned from low/moderate to high levels (McNemar-Bowker on 3×3 table, p=0.157), although these were nonsignificant. Conclusion: This pilot study demonstrates that structured CR significantly improves HRQoL in HF patients, with robust psychometric properties of the CHFQOLQ-20. The greatest gains in physical function align with enhanced functional capacity and hemodynamic adaptation. These findings support CR integration into HF management protocols in resourceconstrained settings, providing a scalable, evidence-based approach to patient-centered care in Cameroon.

Keywords

<p>Heart failure; Cardiac rehabilitation; CHFQOLQ-20; Healthrelated quality of life; Cronbach’s alpha; Sub-Saharan Africa</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Heart failure (HF) affects over 64 million people globally and is a leading cause of hospitalisation and cardiovascular death [1]. In sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), the burden is rising fastest due to uncontrolled hypertension, rheumatic heart disease, and peripartum cardiomyopathy [2]. Unlike high-income countries where HF typically affects patients >70 years, the mean age in SSA is 48–61 years, with dominant non-ischaemic aetiologies (hypertension and rheumatic/valvular) and intra-hospital mortality ranging from 3.7-19% [3,4].

Beyond mortality, HF profoundly impairs health-related quality of life (HRQoL) through dyspnoea, fatigue, emotional distress, cognitive dysfunction, and social isolation [5]. Patients often value health-related quality of life as highly as survival [6]. While generic instruments like the EQ-5D and SF-36 are widely used for economic evaluation, they may lack sensitivity to heart failure (HF)-specific symptoms such as breathlessness and fatigue and therefore, condition-specific tools, such as the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire (KCCQ), and Chronic heart failure health-related quality of life questionnaire (CHFQOLQ-20) are better suited to detect meaningful changes in disease severity, particularly for capturing smaller but clinically important improvements [7,8].

International guidelines (ESC 2021, ACC/AHA 2022) give comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation (CR) a Class I, Level A recommendation for HF [9,10]. In HF patients with reduced ejection fraction, exercise training consistently improves disease-specific health-related quality of life (significant Minnesota Living with Heart Failure Questionnaire (MLWHFQ) reductions, p≤0.001), exercise capacity, NYHA class and, in some trials, mood (Zung Depression Scale p=0.005), whereas effects on depression and readmissions remain inconsistent [11-13]. In In HF patients with preserved ejection fraction, exercise training yields comparable HRQoL benefits (MLWHFQ ~5-point lower, SF-36 gains in physical, vitality and emotional domains, KCCQ gains up to 11 points with moderate continuous training) and reduces depression (p=0.029), often independently of changes in peak VO2 or six minute walking test distance (6MWT) [14-16].

However, extrapolation to SSA is inappropriate as patients are younger, present later, have limited access to guideline-directed medical therapy, and face extreme socioeconomic barriers [4]. Structured CR programs are virtually absent; a 2019 global survey found CR programs in only 17.0% of African countries and this may be due to barriers such as lack of infrastructure, trained staff, funding, and patient transport [17]. This is worsened by the paucity of evidence on non-pharmacological interventions for HF in SSA [18].

This pilot study therefore evaluated, for the first time in Central Africa, the impact of a structured, low-cost, hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation program on HRQoL, NYHA functional class, and self-confidence in Cameroonian patients with stable chronic HF. We hypothesised that even a brief, resource-adapted intervention would produce clinically meaningful improvements, providing proof-of-concept for scalable CR models across SSA.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting: This was a prospective cohort study using a pre-post quai-experimental design. The study was conducted at the Ambulatory Cardiac Rehabilitation Unit located within the Sports complex of Laquintinie Hospital, Douala, Cameroon from May to October 2025.

2.2. Participants: Eligible patients were adults (≥21 years) with clinically stable chronic HF by echocardiography within 3 months, NYHA functional class I–III, on guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) for ≥4 weeks, and able to provide consent. Exclusion criteria included acute decompensation within 30 days, uncontrolled arrhythmias, severe comorbidities (e.g., end-stage renal disease, active malignancy), cognitive impairment precluding questionnaire completion, or contraindications to exercise (unstable angina, severe aortic stenosis). Consecutive sampling was employed from outpatient and inpatient clinics until the target sample was reached.

2.3. Variables and Data Sources

2.3.1. Primary outcome: HRQoL assessed by the CHFQOLQ-20, a 20-item self-administered questionnaire with Likert-scale responses (0–5), yielding a total score (0–100) and four domain scores: physical (8 items), cognitive (3 items), general health (4 items), mental (5 items) with higher scores indicating better HRQoL [7]. The CHFQOLQ-20 was selected for its brevity, strong psychometric properties, and specific validation in chronic heart failure populations, enabling sensitive capture of multidimensional HRQoL changes with minimal patient burden. Cronbach’s alpha for the instrument was 0.83 pre-CR and 0.93 post-CR overall, with domain alphas ≥0.75 (physical 0.88/0.92; others >0.70), indicating excellent reliability in this study. The instrument was translated to French using forward-backward translation, validated and administered by a trained physician at baseline and immediately post-CR.

2.3.2. Secondary outcomes: NYHA class, determined by cardiologist assessment. Self-confidence measured via a single 5-point Likert item ("Do you have self-confidence?") grouped into low (no confidence at all and a little confidence), moderate (moderate confidence), high (much confidence, extreme confidence). Safety was evaluated by recording all adverse events during CR sessions. Baseline data included demographics, HF aetiology, LVEF, comorbidities, medications, and laboratory parameters (NT-proBNP, haemoglobin) when available.

2.4. CR program: The CR program comprised at least ten supervised outpatient sessions (thrice weekly for 5 weeks), each lasting 60 minutes: 10-min warm-up, 30-min aerobic exercise, 10-min resistance training (bodyweight or light weights, 1–2 sets of 10–15 repetitions for major muscle groups), and 10-min cool-down/education. Sessions were led by a trained general practitioner, nurse and physical coach, with cardiologist oversight. Education covered diet, medication adherence, symptom monitoring, and psychosocial support. Intensity was individualised based on baseline 6-minute walk test (6MWT) if feasible; otherwise, symptom-limited.

2.5. Bias: Selection bias was minimised by consecutive enrolment, measurement bias by standardised administration. The effect on HRQoL may have been overestimated since no control group without exposure to CRE program was included and therefore changes may reflect expected time-associated changes. However, the pre-post design permitted robust comparative analysis using the same patients as controls.

2.6. Sample size: Sample size was calculated to detect a minimal clinically important difference of 5 points on the HRQOL total score in chronic heart failure [13]. Using a paired t-test (α=0.05, power=80%), pre–post correlation r=0.70, and standard deviation of paired differences of 7.5 points, the required sample size was: n = [(1.96 + 0.84)² × (1–0.70) × 7.5²] / 5² ≈ 10 patients. Thus, enrolment of 10 participants provides sufficient power to detect a clinically meaningful improvement in health-related quality of life.

2.7. Statistical Methods: Data were analysed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp.). Normality was confirmed by Shapiro-Wilk test. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± SD or median (IQR) if skewed; categorical as frequencies (%). Pre–post comparisons used paired t-tests for CHFQOLQ-20 scores (with 95% confidence intervals [CI] for differences) and Wilcoxon signed-rank for ordinal data if needed. NYHA transitions and Self-confidence (3 levels) were analysed with McNemar test (2×2) for improvement vs. no change/worsening. Internal consistency was assessed via Cronbach’s alpha (≥0.70 acceptable). Two-sided p<0.05 was significant. Missing data were handled by listwise deletion (none occurred).

2.8. Ethical considerations: Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee for Research on Human Health (Reference: 5057/CEI-UDo/07/2025/M). All participants provided written informed consent in French or English.

3. Results

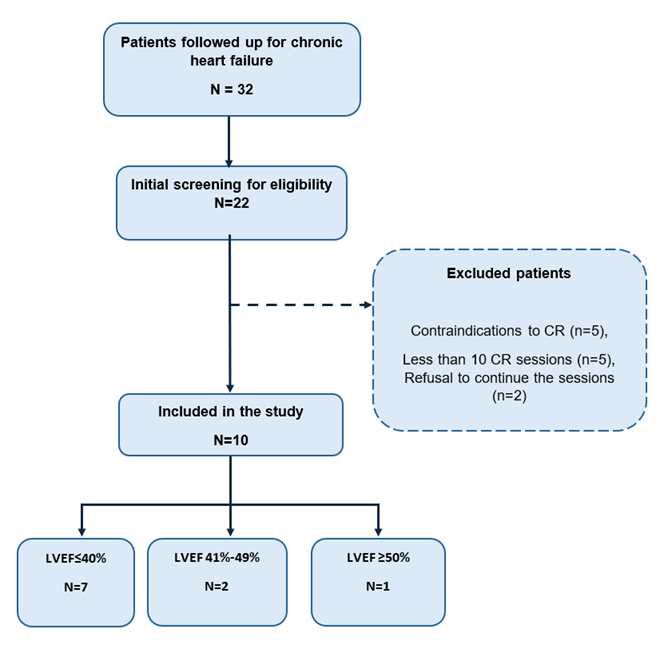

3.1. Participant flow and baseline characteristics: Of 22 screened patients, 10 were enrolled and completed the study. Reasons for non-enrolment included contraindications to CR (n=5), less than 10 sessions (n=5), refusal to continue the sessions (n=2) as shown in Figure 1. Table 1 summarizes baseline characteristics. Median age was 63.5 years (IQR 61.3-71.0); 50% were male. HF aetiology was predominantly dilated cardiomyopathy (40%). Mean LVEF was 31.7 ± 10.52%; 70% were NYHA II. All were on GDMT (ACEI/ARB/ARNI 100%, beta-blockers 90%, SGLT2i 90% and MRA 10%).

LVEF= Left Ventricular Ejection Fraction; CR= Cardiac Rehabilitation.

|

Characteristics |

Value |

|

Median Age in years (Interquartile range) |

63.5 (61.3-71.0) |

|

Male sex |

5 (50%) |

|

Mean LVEF, % (± SD) |

31.7 ± 10.5 |

|

Heart failure type |

|

|

HFrEF |

7 (70%) |

|

HFmrEF |

2 (20%) |

|

HFpEF |

1 (10%) |

|

NYHA class I / II / III |

2 (20%) / 7 (70%) / 1 (10%) |

|

HF Aetiology |

|

|

Dilated cardiomyopathy |

4 (40%) |

|

Hypertensive |

2 (20%) |

|

Indeterminate |

2 (20 %) |

|

Peripartum |

1 (10 %) |

|

Ischaemia |

1 (10 %) |

|

Guideline-directed medical therapy |

|

|

ACEI/ARB/ARNI |

10 (100%) |

|

Beta-blocker |

9 (90%) |

|

SGLT2 inhibitor |

9 (90%) |

|

Mineralocorticoid receptor antagonist |

1 (10%) |

|

Systolic BP, mm Hg |

131.2 ± 31.1 |

|

Heart rate, beats/min |

71.2 ± 11.4 |

|

BMI, kg/m² |

27.9 ± 4.1 |

ACEI=angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor. ARB=angiotensin-receptor blocker. ARNI=angiotensin receptor–neprilysin inhibitor. BMI=body-mass index. BP=blood pressure. HFmrEF=heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction. HFpEF=heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. HFrEF=heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. LVEF=left ventricular ejection fraction. NYHA=New York Heart Association. SGLT2=sodium-glucose cotransporter-2. SD= Standard Deviation.

Table 1: Baseline Participant Characteristics (n=10).

3.2. Functional capacity

After the cardiac rehabilitation programme, participants showed substantial improvements in functional capacity. The 6-minute walk distance increased by a mean of 106.5 m (95% CI 50.1–162.9, p = 0.006), peak oxygen uptake (VO2) rose by 10.7 mL/kg/min (95% CI 5.9–15.5, p = 0.001), corresponding to an impressive 68% relative increase, and metabolic equivalents (METs) improved by 2.5 METs (p <0.001).

|

Variable |

Baseline (mean ± SD) |

Post-rehabilitation (mean ± SD) |

Mean difference (95% CI) |

p-value |

|

6-MWT (m) |

363.5 ± 128.1 |

470.0 ± 91.0 |

106.5 (50.1 to 162.9) |

0.006 |

|

Peak VO2 (mL/kg/min) |

15.6 ± 3.7 |

26.3 ± 9.9 |

10.7 (5.9 to 15.5) |

0.001 |

|

METs |

4.1 ± 2.2 |

6.6 ± 3.3 |

2.5 (1.5 to 3.5) |

<0.001 |

SD= Standard deviation; METs=Metabolic Equivalents; 6-MWT= six minute walking test distance

Table 2: Changes in functional capacity before and after CR (N = 10).

3.3. Primary Outcome: HRQoL

HRQoL assessed by the CHFQOLQ-20, a 20-item self-administered questionnaire with Likert-scale responses (0–5), yielding a total score (0– 100) and four domain scores: physical (8 items), cognitive (3items), general health (4 items), mental (5 items) with higher scores indicating better HRQoL [7]. The CHFQOLQ-20 was selected for its brevity, strong psychometric properties and specific validation in chronic heart failure populations,enabling sensitive capture of multidimensional HRQoL changes with minimal patient burden. Cronbach’s alpha for the instrument was 0.83 pre-CR and 0.93 post-CR overall, with domain alphas ≥0.75 (physical 0.88/0.92; others >0.70), indicating excellent reliability in this study. The instrument was translated to French using forward-backward translation, validated and administered by a trained physician at baseline and immediately post-CR.

3.4. Secondary Outcomes

NYHA class improved in 4 patients (40%; 3 from II to I, 1 from III to II), remained stable in 6 (McNemar p=0.344). Self-confidence shifted markedly: 6 patients (60%) transitioned from low/moderate to high (McNemar-Bowker p=0.157). No adverse events occurred.

4. Discussion

This pilot study provides the first prospective evidence from Central Africa that a structured, cardiac rehabilitation (CR) programme significantly improves health-related quality of life (HRQoL) in patients with chronic heart failure (CHF). Using the recently validated CHFQOLQ-20, total HRQoL score increased by 17.4 points (70.3 ± 11.2 to 87.7 ± 10.7; p<0.001; Cohen’s d=1.58), with highly significant gains across all domains and an impressive 13.3-point improvement in physical function. Functional capacity also rose markedly (6MWT +106 m, peak VO2 +68%) [7]. The CHFQOLQ-20 demonstrated excellent internal consistency in this population (Cronbach’s α 0.83-0.93) and 100% completion rates.

The magnitude of HRQoL improvement far exceeds that typically reported in high-income settings. A cochrane meta-analyses of CR in HFrEF has shown mean MLHFQ reductions of -7.11 points (95% CI -10.49 to -3.73) [19], while KCCQ gains >5 points in 45% of patients in the HF-Action study [20]. The present 10-session programme achieved a 17.4-point rise on a 0–100 scale with the CHFQOLQ-20. Unlike longer instruments (KCCQ completion 51% in routine UK clinics [21]), the brevity and cultural acceptability of the CHFQOLQ-20 likely contributed to full adherence in our setting.

The greatest gains in the physical domain mirror objective increases in exercise capacity (6MWT +106 m, peak VO2 +68%) and potentially reflect reduced dyspnoea and fatigue, symptoms that are dominant in African HF populations [3]. Significant improvements in cognitive and mental domains are particularly noteworthy given the dedicated cognitive factor of the CHFQOLQ-20, which is absent from most legacy instruments [7]. Enhanced cerebral perfusion, reduced neurohormonal activation, increased self-efficacy (60% shifted to high self-confidence), and group psychosocial support likely acted synergistically. The absence of any adverse events confirms the safety of supervised, moderate-intensity exercise even at a mean LVEF of 32%.

Strengths include the prospective pre–post design, objective functional measures, 100% retention and questionnaire completion, and the first published use of the CHFQOLQ-20 outside its original Iranian validation, reinforcing its cross-cultural robustness. Limitations are the small sample size (n = 10), single-centre pilot nature, lack of a control group (preventing exclusion of regression-to-the-mean or placebo effects), short-term follow-up, and absence of prognostic biomarkers or hospitalisation data to correlate with HRQoL gains.

This pilot provides compelling proof-of-concept that brief, CR is feasible, safe, and remarkably effective in sub-Saharan Africa. The CHFQOLQ-20 has emerged as an ideal outcome tool for resource-constrained settings, short, cognition-inclusive, and highly sensitive to change. Larger multicentre randomised trials are now urgently needed across Africa to confirm efficacy, sustainability, and impact on hard clinical endpoints. National heart failure programmes and international guidelines should prioritise scalable CR models, while clinicians should routinely incorporate brief disease-specific HRQoL tools to deliver truly patient-centred care in low- and middle-income regions.

5. Conclusion

This pilot study demonstrates that a simple 10-session hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation programme is safe, highly feasible and produces strikingly large improvements in health-related quality of life among Cameroonian patients with chronic heart failure. The CHFQOLQ-20 proved to be an excellent, practical and sensitive tool in a sub-Saharan African setting. These findings provide the first prospective evidence from Central Africa that structured cardiac rehabilitation can be successfully implemented with minimal resources and should be integrated into routine heart failure management across the region. Larger randomised controlled trials are now warranted to confirm the sustainability of benefits and their impact on hospitalisations and survival.

5.1. What is already known on this topic

- Chronic heart failure profoundly impairs health-related quality of life (HRQoL), often to a degree that patients value as highly as survival itself, yet HRQoL is rarely assessed in sub-Saharan Africa.

- International guidelines give comprehensive cardiac rehabilitation a Class I recommendation for heart failure, with consistent evidence from high-income countries of moderate improvements in disease-specific HRQoL (typically 5–11 points on KCCQ or MLHFQ) and exercise capacity.

- Structured cardiac rehabilitation programmes are virtually non-existent in most African countries, and no prospective data have previously documented the effect of any form of cardiac rehabilitation on HRQoL in sub-Saharan African heart failure patients.

5.2. What this study adds

- Provides the first prospective evidence from Central Africa that a brief (10-session) hospital-based cardiac rehabilitation programme is safe, achieves 100% adherence and retention, and produces very large improvements in multidimensional HRQoL (Δ 17.4 points on CHFQOLQ-20; Cohen’s d = 1.58), considerably greater than typically seen in Western trials.

- Demonstrates that the recently developed CHFQOLQ-20 is highly feasible, reliable (Cronbach’s α 0.83–0.93) and sensitive to change in a francophone sub-Saharan African population, including its unique ability to capture improvements in cognitive function.

- Offers proof-of-concept that resource-adapted cardiac rehabilitation can be successfully delivered in a low-income setting using existing hospital infrastructure and multidisciplinary staff, paving the way for scalable, evidence-based non-pharmacological management of heart failure across Africa.

6. Declarations

Acknowledgments: We thank the staff at Laquintinie Hospital and participants for their contributions.

Funding: None.

Ethics approval and consent to participate: Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee for Research on Human Health (Reference: 5057/CEI-UDo/07/2025/M). All participants provided written informed consent before being included in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Patient data were anonymized, coded, and stored on a password-protected computer accessible only to the principal investigator. The study adheres to the STROBE guidelines to ensure transparent, standardized reporting of observational research.

Consent for publication: Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials: The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing Interests: The authors declare no competing interests

Funding: No funding was received for this study.

Acknowledgements: We thank all participants who accepted to get the survey administered.

Author contribution: Study concept and design: DS, ECBL and EMML. Data collection: DS. Analysis and interpretation of data: EMML. Manuscript writing: DS, MSN, HNTK. MS, VD, MC, EMML, RKT, CNN, ECBL and FK. Final approval of manuscript: All authors. KF supervised the study. DS, and EMML had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors agreed to submit the manuscript in its current form.

References

- James SL, Abate D, Abate KH, Abay SM, Abbafati C, Abbasi N, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet 392 (2018): 1789-1858.

- Gallagher J, McDonald K, Ledwidge M, Watson CJ. Heart Failure in Sub-Saharan Africa. Card Fail Rev 4 (2018): 21-24.

- Gtif I, Bouzid F, Charfeddine S, Abid L, Kharrat N. Heart failure disease: An African perspective. Archives of Cardiovascular Diseases 114 (2021): 680-690.

- Siddikatou D, Mandeng Ma Linwa E, Ndobo V, Nkoke C, Mouliom S, et al. Heart failure outcomes in Sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review of recent studies conducted after the 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA guideline release. BMC Cardiovascular Disorders 25 (2025): 302.

- Ventoulis I, Kamperidis V, Abraham MR, Abraham T, Boultadakis A, et al. Differences in Health-Related Quality of Life among Patients with Heart Failure. Medicina (Kaunas) 60 (2024): 109.

- Erceg P, Despotovic N, Milosevic DP, Soldatovic I, Mihajlovic G, et al. Prognostic value of health-related quality of life in elderly patients hospitalized with heart failure. Clin Interv Aging 14 (2019): 935-945.

- Khajavi A, Moshki M, Minaee S, Vakilian F, Montazeri A, et al. Chronic heart failure health-related quality of life questionnaire (CHFQOLQ-20): development and psychometric properties. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 23 (2023):165.

- Rankin J, Rowen D, Howe A, Cleland JGF, Whitty JA. Valuing health-related quality of life in heart failure: a systematic review of methods to derive quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) in trial-based cost–utility analyses. Heart Fail Rev 24 (2019): 549-563.

- Heidenreich PA, Bozkurt B, Aguilar D, Allen LA, Byun JJ, et al. 2022 AHA/ACC/HFSA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Joint Committee on Clinical Practice Guidelines. Circulation 145 (2022): e895-1032.

- McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, Gardner RS, Baumbach A, et al. 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. European Heart Journal 42 (2021): 3599-3726.

- Caraballo C, Desai NR, Mulder H, Alhanti B, Wilson FP, et al. Clinical Implications of the New York Heart Association Classification. Journal of the American Heart Association 8 (2019): e014240.

- Spertus JA, Jones PG, Sandhu AT, Arnold SV. Interpreting the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Clinical Trials and Clinical Care. JACC 76 (2020): 2379-2390.

- Eleyan L, Gonnah AR, Farhad I, Labib A, Varia A, et al. Exercise Training in Heart Failure: Current Evidence and Future Directions. Journal of Clinical Medicine 14 (2025): 359.

- Chrysohoou C, Tsitsinakis G, Vogiatzis I, Cherouveim E, Antoniou C, et al. High intensity, interval exercise improves quality of life of patients with chronic heart failure: a randomized controlled trial. QJM 107 (2014): 25-32.

- Conraads VM, Beckers P, Vaes J, Martin M, Van Hoof V, et al. Combined endurance/resistance training reduces NT-proBNP levels in patients with chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J 25 (2004): 1797-1805.

- Laoutaris ID, Piotrowicz E, Kallistratos MS, Dritsas A, Dimaki N, et al. Combined aerobic/resistance/inspiratory muscle training as the ‘optimum’ exercise programme for patients with chronic heart failure: ARISTOS-HF randomized clinical trial. Eur J Prev Cardiol 28 (2021): 1626–35.

- Turk-Adawi K, Supervia M, Lopez-Jimenez F, Pesah E, Ding R, et al. Cardiac Rehabilitation Availability and Density around the Globe. eClinicalMedicine 13 (2019): 31-45.

- Dugal JK, Malhi AS, Ramazani N, Yee B, DiCaro MV, et al. Non-Pharmacological Therapy in Heart Failure and Management of Heart Failure in Special Populations—A Review. J Clin Med 13 (2024): 6993.

- Long L, Mordi IR, Bridges C, Sagar VA, Davies EJ, et al. Exercise-based cardiac rehabilitation for adults with heart failure. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2019: CD003331.

- Luo N, O’Connor CM, Cooper LB, Sun JL, Coles A, et al. Relationship between Changing Patient-Reported Outcomes and Subsequent Clinical Events in Patients with Chronic Heart Failure: Insights from HF-ACTION. Eur J Heart Fail 21 (2019): 63-70.

- Gallagher AM, Lucas R, Cowie MR. Assessing health-related quality of life in heart failure patients attending an outpatient clinic: a pragmatic approach. ESC Heart Fail 6 (2019): 3-9.

Impact Factor: * 5.6

Impact Factor: * 5.6 Acceptance Rate: 74.36%

Acceptance Rate: 74.36%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks