Arterial Pulse Synchronized Contractions (PSCs)

Allen Mangel1* and Katherine Lothman2

1Mangel Consulting, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

2Department of Medical Communications, RTI Health Solutions, Research Triangle Park, NC, USA

*Corresponding author: Allen Mangel, Mangel Consulting, 303 Telluride Trail, Chapel Hill, NC 27514, USA.

Received: 03 December 2025; Accepted: 12 December 2025; Published: 18 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Allen M, Katherine L. Arterial Pulse Synchronized Contractions (PSCs). Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine. 9 (2025): 499-503.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookKeywords

<p>Pulse Synchronized Contractions; Aorta; Cardiac; Neural Modulation; Pulse Wave</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Diseases of the cardiovascular system account for a significant proportion of morbidity and mortality world-wide. Understanding the behavior of the arterial tree is, therefore, paramount to both the diagnosis and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. One of the platforms underpinning the understanding of the functionality of the heart and vasculature is embodied by the Windkessel Hypothesis [1]. This platform was proposed over a century ago by Dr. Otto Frank and simply states that the smooth muscle walls of large arteries behave as passive elastic tubes in vivo, are distended by the pulse wave, and do not undergo rhythmic activation during the cardiac cycle.

Previously, we have provided evidence [2-13] in contrast to the Windkessel Hypothesis. In the current editorial we provide a summary of the data refuting that hypothesis.

2. Background: How Did We Get Here?

What was believed in Gastrointestinal Smooth Muscle?

An increase in intracellular calcium activates contractions in muscle cells. Smooth muscle cells are long, narrow-diameter cells, and it was believed that an influx of calcium could serve as the sole source of activator calcium for contractions following membrane potential depolarization. It was believed no depolarization-mediated release of intracellularly stored calcium occurred [13].

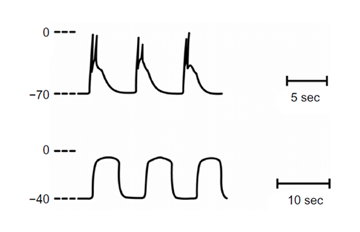

Normal slow waves with spikes (upper trace). Following incubation in calcium-free solution an alternative rhythmicity developed, denoted prolonged potentials (lower trace). In this solution, membrane potential depolarizes [14,15].

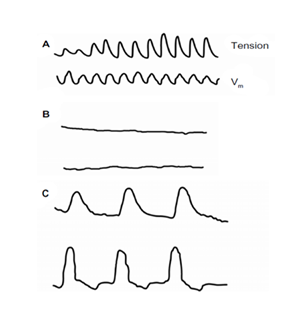

Mechanical and Electrical Activity in normal saline (A); after initial exposure to calcium-free solution (B); and after longer incubation in calcium-free solution (C). Unexpectedly, contractions developed in calcium free solution, triggered by membrane depolarization (C). Electrical recordings with extracellular pressure electrodes [14,15].

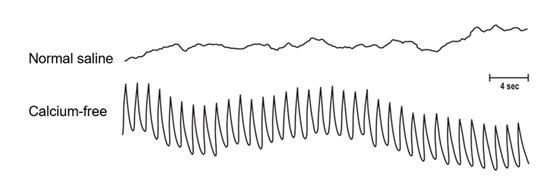

Rabbit aortic segments incubated in normal saline are electrically quiescent (upper trace). In calcium-free solution, a fast, rhythmic electrical event was produced (lower trace). However, the muscle segments remained mechanically quiescent in vitro. Electrical recordings with pressure electrodes [16].

3. Aortic Smooth Muscle Contractions In Vivo

State of the Art: Windkessel Hypothesis (Otto Frank [1])

The prevailing hypothesis describing the behavior of the smooth muscle wall of the large arteries in vivo was that the wall does not contract in synchrony with the cardiac cycle but, rather, behaves as a passive elastic tube being rhythmically distended by pulsatile pressure changes. Neural input may modulate tone. Thus, it was believed that there was no arterial smooth muscle rhythmicity in synchrony with the cardiac cycle. This has been one of the platforms in cardiovascular physiology for over a century.

Our Hypothesis

Based on the unexpected ability of the aortic smooth muscle wall to generate fast rhythmic electrical activity in calcium-free solution (see Figure 3), we sought to determine if the aortic smooth muscle wall could potentially show fast rhythmic contractile activity in vivo.

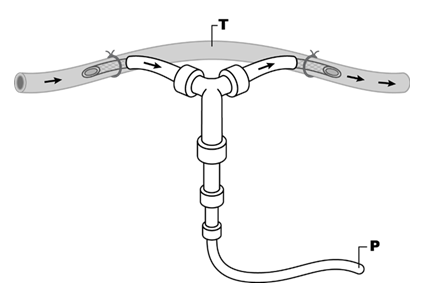

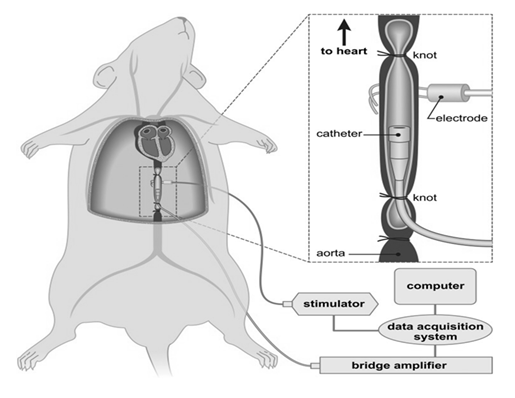

Figure 4: Recording technique for measurement of contractile activity in the in vivo aorta that was used in most studies. Animals were anesthetized and segments of aorta had blood flow bypassed and tension (T) recorded from the bypassed segment. Pulse pressure changes (P) were recorded from the non-bypassed segment. Arrows represent blood flow [12].

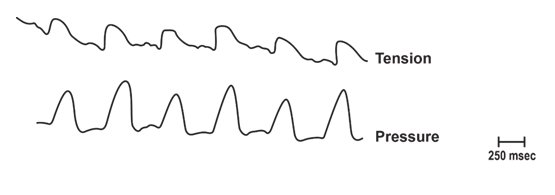

Using the recording technique described (see slide 4), rhythmic tension changes were recorded with a 1:1 correspondence to the pulse wave. Due to the correlation of tension changes with the pulse wave, these in vivo contractions were denoted as pulse synchronized contractions or PSCs. This is in contrast to the Windkessel Hypothesis [2].

Considerable Effort was Expended Testing Whether PSCs Could be Due to an Artifact from other Movements

These efforts included:

- • Eliminating the pulse wave as an artifact

- • Eliminating cardiac contractility as an artifact

- • Dispelling the prevailing theory that arterial smooth muscle cannot “contract as fast” as the heartbeat/pulse wave

Continuation of PSCs in Bled Animals: Right Atrial Pacing

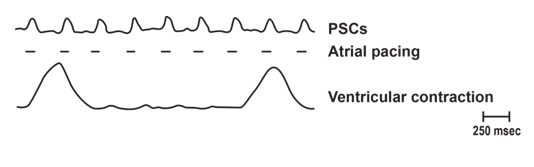

In this example of right atrial pacing in a bled rabbit, PSCs followed the pacing rate. In this and some other animals, heart block developed with corresponding large amplitude ventricular contractions. The ventricular contractions occurred at a slower rate than atrial pacing, but the PSCs followed the pacing rate. This series of experiments supports both: (1) the pacemaker for PSCs may reside in the right atrium and (2) that PSCs are not secondary to a movement artifact from ventricular contractions or from the pulse wave (as animals were bled) [2].

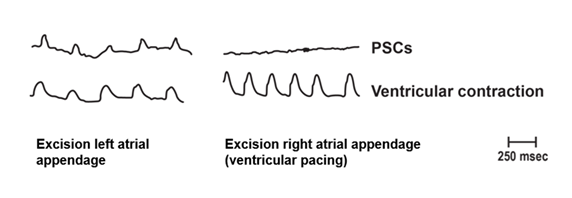

Following bleeding of rabbits, spontaneous PSCs continued. Ventricular muscle contractions were also recorded. To enhance the magnitude of ventricular muscle contractions, pacing of the ventricles occurred (right sided panel). These studies: (a) eliminated the pulse wave as an artifact, as animals were bled; (b) eliminated cardiac contractions as an artifact, as following excision of the right atrial appendage, and ventricular contractions paced to supra baseline levels, PSCs were not produced; and (c) suggested the PSC pacemaker is in the right atrium as excision of the right, but not left atrial appendage, abolished PSCs [2].

PSC Frequency

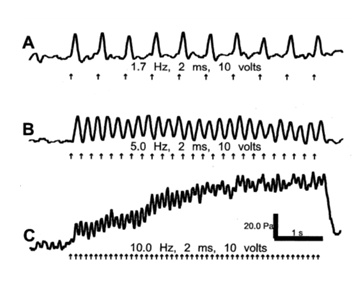

To confirm that the arterial smooth muscle wall is capable of contracting at the frequency of the heartbeat, electrical stimulation of the aorta in vivo was performed.

As shown above, PSCs followed the stimulation frequency. Above a frequency of 5 Hz, the muscle also developed a tetanus like state (Trace C). Arrows represent timing of stimulation [4].

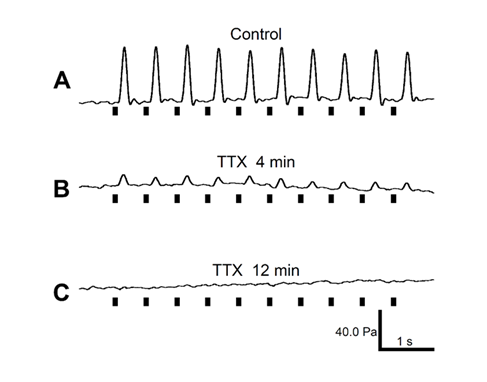

Electrically enhanced rat aortic contractions in vivo (A) were eliminated by topical application of the neural blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX) (B,C). Alpha-blockers also reduced PSC activity. Black bars represent timing of stimulation [4].

Studies By Dr. Heyman

Dr. Heyman and colleagues in a series of papers published in Acta Med Scand 1955, 1957, 1959, 1961 and 1962 showed [17-21]:

- • Extra-arterially recorded brachial pulses sometimes preceded intra-arterial pulses. This suggested arterial diameter may vary in advance of pressure changes during the cardiac cycle.

- • Stellate ganglion block eliminated the difference between intra- and extra-arterially recorded pulse waves.

- • They concluded: “the behaviour of the artery is contradictory to the principal of passive elasticity….”

- • Significantly, they demonstrated this behavior in humans.

Conclusions [6,9,10,11]

- • The smooth muscle wall of the large arteries is capable of rapid contractions (PSCs) at the rate of the heartbeat.

- • The contractions are neurogenic in origin as evidenced by blockade by TTX and are not secondary to movement artifacts from the pulse wave or heartbeat.

- • The pacemaker for PSCs is in the right atrium.

- • Direct electrical stimulation of the nerves within the aorta yields similar contractile activity as PSCs.

- • PSCs represent a modified platform to understand the etiology of cardiovascular diseases allowing for the development of new therapeutic targets.

Future Pursuits [5,6,12]

- • Englesbe et al. [22] have shown that following cardiac transplant, some patients developed aortic aneurysms which may dissect.

- • With cardiac transplant, neural continuity down the aorta from the right atrium would be disrupted.

- • The phasing of PSCs suggests that they may limit aortic wall distension from the pulse wave, thus decreasing shearing forces on the vascular wall.

- • With neural pathway disruption, associated with cardiac transplant, PSCs may be eliminated in large arteries.

- • Future studies: Are disruption of PSCs involved in the development of aortic aneurysms and aortic dissection in humans post cardiac transplant?

- Other avenues of investigation to pursue: are PSCs altered in states of hypertension or diabetes?

References

- Frank O. Die Grundform des Arteriellen Pulses. Zeitschrift fur Biologie 37 (1899): 483-526.

- Mangel A, Fahim M, van Breemen C. Control of vascular contractility by the cardiac pacemaker. Science 215 (1982): 1627-1629.

- Mangel A. Does the aortic smooth muscle wall undergo rhythmic contractions during the cardiac cycle? Experimental and Clinical Cardiology 20 (2014): 6844-6851.

- Sahibzada N, Mangel A, Tatge J, Dretchen KL, Franz MR, et al. Rhythmic aortic contractions induced by electrical stimulation in vivo. PLoS One 10 (2015): e0130255.

- Mangel A. A changing paradigm for understanding the behavior of the cardiovascular system. Journal of Clinical & Experimental Cardiology 8 (2017): 496.

- Mangel A, Lothman K. Emergence of a new paradigm in understanding the cardiovascular system: pulse synchronized contractions. Cardiovascular Pharmacology 6 (2016): 220.

- Mangel A, Lothman K. Pulse synchronized contractions (PSCs): a call to action. Open Journal Cardiology and Heart Disease 1 (2018).

- Mangel A, Mangel T. Pulse synchronized contractions: Rhythmic contractions in large arteries in synchrony with the heart beat. J Cardiol Res 2 (2019): 13.

- Lothman K, Mangel A. Pulse Synchronized Contractions (PSCs) Journal of Cardiology and Cardiovascular Medicine 4 (2019): 199-200.

- Mangel A, Lothman K, Mangel T. Pulse Synchronized Contractions: A Review. EC Cardiology 7(2020): 61-66.

- Mangel T, Lothman K, Mangel A. Pulse Synchronized Contractions (PSCs): An Invited Review. EC Cardiology 8(2021) 18-21.

- Mangel T, Lothman K, Mangel A. A proposed physiologic role for pulse synchronized contractions (PSCs): Expert Opinion. Cardiology and Vascular Research 6 (2022): 1.

- Marion S, Mangel A. From depolarization-dependent contractions in gastrointestinal smooth muscle to aortic pulse-synchronized contractions. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology 7 (2014): 61-66.

- Mangel A, Nelson D, Connor J, Prosser C. Contractions of cat small intestinal smooth muscle in calcium free solution. Nature 281 (1979): 582-583.

- Mangel A, Nelson D, Rabovsky J, Prosser C, Connor J. Depolarization induced contractile activity of smooth muscle in calcium free solution. Am J Physiology 242 (1982): C36-40.

- Mangel A, van Breemen C. Rhythmic electrical activity in rabbit aorta induced by EGTA. J Exp Biol 90 (1981): 339-342.

- Heyman F. Movements of the arterial wall connected with auricular systole seen in cases of atrioventricular heart block. Acta Med Scand 152 (1955): 91-96.

- Heyman F. Comparison of intra-arterially and extra-arterially recorded pulse waves in man and dog. Acta Med Scand 157 (1957): 508-510.

- Heyman F. Extra- and intra-arterial records of pulse waves and locally introduced pressure waves. Acta Med Scand 163 (1959): 473-475.

- Heyman F. Pulse synchronous movements of the arterial wall peripheral to an obstruction in the circulation of the arm. Acta Med Scand 169 (1961): 87-93.

- Heyman F, Sternberg K. The effects of stellate ganglion block on the relationship between extra- and intra-arterially recorded brachial pulse waves in man. Acta Med Scand 171 (1962): 9-11.

- Englesbe M, Wu A, Clowes A, Zierler RU, et al. The prevalence and natural history of aortic aneurysms in heart and abdominal organ transplant patients. J Vasc Surg 37 (2003): 27-31.

Impact Factor: * 5.6

Impact Factor: * 5.6 Acceptance Rate: 74.36%

Acceptance Rate: 74.36%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks