Kosakonia radicincitans bSL2 as a PGPB: Effect on Lactuca sativa L. Seed Germination and Acute Toxicity Assessment in Rats

Possetto, Paola A1, Teves, Mauricio R2, Calvo, Juan A3, Wendel, Graciela H2, Navarta, L. Gastón1, Sansone, M. Gabriela1, Calvente, Viviana E1*

1Área de Tecnología Química y Biotecnología, Facultad de Química Bioquímica y Farmacia Universidad Nacional de San Luis, Argentina

2Área de Farmacología, Facultad de Química Bioquímica y Farmacia Universidad Nacional de San Luis, Argentina

3Área de Ecología, Facultad de Química Bioquímica y Farmacia Universidad Nacional de San Luis, Argentina

*Corresponding Authors: Viviana Edith Calvente, Área de Tecnología Química y Biotecnología, Facultad de Química Bioquímica y Farmacia Universidad Nacional de San Luis, Argentina.

Received: 19 December 2025; Accepted: 26 December 2025; Published: 12 January 2026

Article Information

Citation: Possetto, Paola A, Teves, Mauricio R, Calvo, Juan A, Wendel, Graciela H, Navarta, L. Gastón, Sansone, M. Gabriela, Calvente, Viviana E. Kosakonia radicincitans bSL2 as a PGPB: Effect on Lactuca Sativa L. Seed Germination and Acute Toxicity Assessment in Rats. International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences. 16 (2026): 01-10.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

In response to the growing global demand for food and the need for sustainable and safe agricultural practices, this study evaluated the plant growth-promoting potential of the Kosakonia radicincitans bSL2 strain, its effect on Lactuca sativa L. seed germination, and its acute oral toxicity in Wistar rats. The objective was to assess its feasibility as an active ingredient in microbial-based biostimulants.

K. radicincitans bSL2, originally isolated from apples in San Luis Province, Argentina, is preserved at the Industrial Microbiology Laboratory of the National University of San Luis. It exhibits typical plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) traits, including nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, indole-3- acetic acid (IAA) production, and siderophore biosynthesis. The strain was successfully cultivated in a low-cost medium derived from brewing by-products, yielding high biomass.

Its agronomic potential was tested by applying bacterial biomass to seeds of different lettuce cultivars under laboratory and nursery conditions. Results showed significant improvements in germination, with increases of 9–12% in laboratory assays and around 10% in nursery trials compared to controls.

For toxicological evaluation, acute oral toxicity tests were performed in male and female Wistar rats using bacterial suspensions from 108 to 10¹² CFU/mL. No mortality, clinical signs, or significant changes in body weight or organ mass were detected.

These findings indicate that K. radicincitans bSL2 is a safe and effective microbial agent with potential for agricultural biostimulant development. This is the first report describing the application of Kosakonia in this region.

Keywords

<p><em>Kosakonia radicincitans</em>; Acute toxicity; Lactuca sativa; Germination; PGPB</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

At a global level, the availability of fruits and vegetables remains insufficient to meet the daily requirements of a healthy diet. Shifts in consumption patterns and increasing urbanization are negatively impacting food security and human nutrition. Therefore, transformations in agri-food systems must be directed toward the promotion of affordable and nutritious diets [1]. Plant health is closely linked to soil health, and both are influenced by the microbial communities inhabiting them. Microbiomes have a significant impact on agricultural productivity and are considered crucial for achieving sustainable and sufficient food production [2].

The inclusion of a microorganism as an active agent for agricultural application requires evidence of both plant growth-promoting ability and safety. In this context, plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) are primarily soil-dwelling organisms that colonize the rhizosphere and phyllosphere of plants and, under certain conditions, efficiently enhance plant growth and tolerance to phytopathogens [3].

These microorganisms influence plant metabolism through direct, indirect, or combined mechanisms. Direct mechanisms improve nutrient availability and plant nutrition through biological nitrogen fixation, synthesis of vitamins and enzymes, inorganic phosphate solubilization, organic phosphate mineralization, sulfur oxidation, nitrite production, nitrate accumulation, and the synthesis of plant growth regulators (auxins, gibberellins, cytokinins), which enhance seed germination and root hair development, thus improving absorption capacity [4-6]. Indirect mechanisms include biocontrol of phytopathogens via antimicrobial compounds, lytic enzymes, nutrient and niche competition, siderophore production (sequestering iron to inhibit pathogen development), and stimulation of systemic resistance (ISR) in plants [7,8].

The specific mechanism of action of a given PGPB species is often difficult to predict, as their effects may vary depending on the strain and conditions [9,10].

Large-scale cultivation of PGPB requires low-cost culture media. Standard laboratory media are often too expensive for industrial biomass production. As a result, several studies have focused on developing and evaluating the efficiency of alternative, cost-effective media [11,12].

The use of PGPB in the agri-food sector must comply with regulatory frameworks established in each jurisdiction. In Argentina (SAGyP, 2023) bioinputs are defined as biological products composed of microorganisms, extracts, or bioactive compounds derived from them, intended for use in agricultural, food, agro-industrial, and bioenergy production [13]. Numerous species of the genus Kosakonia have been isolated from various plants and function as beneficial bacteria in agriculture Kosakonia radicincitans is widely recognized for its PGPB potential due to its ability to produce siderophores [14], indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), solubilize phosphate, fix nitrogen, and synthesize glycine-betaine [15]. Mutations or loss of any of these traits may reduce its effectiveness as a PGPB [16].

Several studies have reported its ability to promote plant growth and antagonize phytopathogens, thus improving crop yield and quality [17,18]. K. radicincitans has demonstrated PGPB activity in crops such as radish [19], yerba mate (Ilex paraguariensis St. Hill) [20], tomato [21], maize [22], sweet rice, potato, sugarcane, cotton, peanut, and pineapple [23].

Although rare, clinical reports of K. radicincitans isolates acting as opportunistic pathogens in humans have emerged: one case in the United States (2016) and another in Austria (2020) [17,24]. In both cases, the isolates were found to share genes or gene clusters with known human pathogens, such as Escherichia coli O157:H7 and yersiniabactin-producing bacteria.

The objective of this study was to investigate the PGPB characteristics of Kosakonia radicincitans bSL2 and its effects on Lactuca sativa L. seed germination, as well as to evaluate its preclinical toxicity in Wistar rats to ensure its safety as a potential active ingredient in agricultural bioinputs.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism

The bacterium Kosakonia radicincitans was isolated from the apples surface, in San Luis Province, Argentina. Identification was carried out at the Industrial Microbiology Laboratory of the Faculty of Chemistry, Biochemistry, and Pharmacy at the National University of San Luis (UNSL), using the Analytical Profile Index Systems API 20 E and API 50 CHE systems (bioMérioux, France) for metabolic profile determination. For molecular identification, Macrogen (Korea) amplified the 16S rRNA sequence using the following bacterial-specific primer set: 785F 5′ (GGA TTA GAT ACC CTG GTA) 3′ and 907R 5′ (CCG TCA ATT CMT TTR AGT TT) 3′. The 16S rDNA sequence analysis revealed that the isolate (accession number: NR_117704.1) shared 99% similarity with K. radicincitans. From this point forward, the strain is referred to as Kosakonia radicincitans bSL2, indicating its geographical origin [14,18]. The microorganism was maintained on YGA medium (yeast extract 5 g/L, glucose 10 g/L, agar 20 g/L) at 4°C. In the culture collection, it was maintained lyophilized with a protecting mixture that consisted of skimmed nonfat milk 10%, yeast extract 0.5% and glucose 1% (SMYG) [18].

2.2. Culture Media and Growth Conditions of K. radicincitans bSL2

2.2a. Culture for Acute Toxicity Studies in Rats

A liquid YGM medium (yeast extract 5 g/L, glucose 10 g/L) was used. Cultures were grown in 1-L baffled Erlenmeyer flasks containing 250 mL of medium and incubated at 28°C on a rotary shaker for 24 h. Cells were harvested by centrifugation at 11,000 rpm for 10 minutes using a Sorvall SS-3 centrifuge (DuPont Instruments, Newton, CT). The pellet was resuspended in 15 mL of 0.05 mol/L potassium phosphate buffer (pH 6.5), centrifuged again, and the biomass was adjusted according to the treatment doses.

2.2b. Culture for in vivo Lettuce Germination Trials

A low-cost culture medium (LCM) was formulated using 70 g/L dried bagasse and 5 g/L dried yeast, sterilized at 121°C. It was inoculated with 10 mL of K. radicincitans bSL2 at a concentration equivalent to 0.5 McFarland per 100 mL of LCM and incubated at 28°C with shaking at 120 rpm for 24 h. The biomass was filtered under aseptic conditions, rinsed twice with sterile distilled water, and adjusted to a concentration of 6 × 108 CFU/mL.

2.3. In vitro Plant Growth-Promoting Traits

The following PGPB traits of K. radicincitans bSL2 were investigated:

- a) Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production, b) Nitrogen fixation, c) Phosphate solubilization, and d) Siderophore production. All experiments were conducted in triplicate.

2.3.1. Indole-3-Acetic Acid (IAA) Production

The bacterium was cultivated under the same conditions described in section 2.2a, using tryptic soy broth (TSB) as the growth medium and evaluated at different incubation times (48, 96, and 120 hours). Culture supernatants were used to detect IAA production using the modified Salkowski colorimetric method, measuring absorbance at 540 nm [25]. IAA concentrations (µg/mL) were calculated based on a standard calibration curve prepared using increasing concentrations of a commercial IAA standard (Fluka Chemie AG).

2.3.2. Nitrogen Fixation

To assess nitrogen fixation capacity, a suspension of K. radicincitans bSL2 adjusted to a 0.5 McFarland standard was inoculated into three nitrogen-free media: NFb (specific for Azospirillum), LGI (semi-selective for Gluconobacter spp.), and JMV (semi-selective for Burkholderia spp.) [26]. Positive results were indicated by visible turbidity and a color change in the medium (pH reduction), reflecting the bacterium’s ability to utilize atmospheric nitrogen and produce ammonium.

2.3.3. Phosphate Solubilization

The microorganism was streaked onto solid medium containing Ca3(PO4)2 as described by Tejera-Hernández et al. [27]. Results were recorded as solubilization halo diameter (mm), colony diameter (mm), and phosphate solubilization index (PSI), calculated as: PSI = (Halo + Colony Diameter in mm) / Colony Diameter in mm.

2.3.4. Siderophore Production

Siderophore production was confirmed based on [14], by cultivating the bacterium in vitamin-free medium with glucose as the sole carbon source, at 28°C for 120 hours. Enterobactin concentration in the supernatant was determined using the Arnow assay.

2.4 Evaluation of Acute Oral Toxicity of K. radicincitans bSL2 in Rats

The potential acute toxicity of K. radicincitans bSL2 was assessed following Guideline No. 423 of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development [28]. The experimental protocol was approved by the Institutional Committee for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (CICUA – Ord. CD No. 009/06) of the Faculty of Chemistry, Biochemistry and Pharmacy at the National University of San Luis (FQByF-UNSL), under Resolution RCD 02-70/2023.

2.4.1. Experimental Animals

Wistar rats (180–200 g) of both sexes were used, provided by the Central Animal Facility of FQByF-UNSL. Animals were housed under controlled environmental conditions: constant temperature (22 ± 3°C), regular air exchange, 50–60% relative humidity, and a 12-hour light/dark cycle (lights on from 07:00 to 19:00). Rats had free access to tap water (supplied via appropriate drinking systems) and standard laboratory chow ad libitum. Animal care and experimental procedures adhered to national guidelines for animal welfare, as outlined in Disposition No. 9236/2023 issued by the National Administration of Drugs, Food and Medical Devices [29].

2.4.2. Experimental Procedure

The experimental design included five groups: one negative control group receiving the vehicle (normal saline) and four treatment groups receiving decreasing doses of K. radicincitans bSL2 biomass (prepared as described in section 2.2a): group a: 1 × 10¹² CFU/mL in 2 mL saline, group b: 1 × 1010 CFU/mL in 2 mL saline, group c: 1 × 108 CFU/mL in 2 mL saline, group d: 1 × 106 CFU/mL in 2 mL saline.

Each group consisted of six rats (three males and three females). Animals received a single oral dose on Day 0 and were observed periodically during the first 24 hours (with particular attention during the initial 4 hours), and then daily for 14 days. Observations focused on mortality and clinical signs of toxicity, including changes in appearance, behavior, and neurological function, following the Irwin screening protocol [30]. At the end of the 14-day observation period, animals were euthanized by carbon dioxide inhalation. The heart, spleen, lungs, liver, kidneys, and reproductive organs (ovaries or testes) were removed, weighed, and expressed as a percentage of total body weight [31]. A macroscopic examination of the organs was performed, and the gastric, duodenal, and colonic mucosa were inspected under a dissecting microscope. Animals were weighed on Days 0, 7, and 14, and weight gain or loss was calculated for each time period (0–7 and 7–14 days). Food intake was recorded during the same intervals.

2.5. Effect of K. radicincitans bSL2 on Lactuca sativa L. Seed Germination

2.5.1. Laboratory Seed Germination Assays

Lactuca sativa seeds were provided by INTA San Luis and included the following cultivars: Capitata (commercially known as butterhead), Grand Rapids (curly type), and White Boston (smooth leaf), the latter provided by the IMPROFOP (Sapem) nursery in San Luis. Classification followed the criteria established by SAGyP, Argentina (2023).

Seeds were disinfected with 1% sodium hypochlorite for 5 minutes and rinsed twice with sterile distilled water. A total of 400 seeds from each cultivar were placed in moist chamber trays, distributed as 50 seeds per tray. Seeds were randomly divided into two groups: 200 were treated with a single 20 µL application of K. radicincitans bSL2 suspension (6 × 108 CFU/mL), and 200 received sterile distilled water (negative control). Trays were incubated in the dark at 20–22°C with 60–80% relative humidity for 7 days.

At the end of the incubation period, the number of germinated and non-germinated seeds was recorded. The experiments were performed in duplicate. The germination rate was expressed as a percentage, calculated using the following formula (1). The procedure followed the guidelines established by the International Rules for Seed Testing [32].

The percentage effectiveness (% E) of K. radicincitans bSL2 as a biostimulant was evaluated in comparison with seeds (negative control), using the formula:

2.5.2. Nursery Germination Assays

White Boston lettuce seeds were treated following the procedure described in section 2.5.1. The substrate used was a basic soil mix consisting of 30% soil, 50% composted horse manure, and 20% sawdust. Both the seeds and substrate were supplied by the nursery. A total of 400 seeds were sown in plastic seedling trays (one seed per cell). Each cell received a single 1 mL spray application of K. radicincitans bSL2 suspension (6 × 108 CFU/mL). A control group of 400 seeds was sprayed with 1 mL of sterile distilled water. Trays were incubated at 20–22°C with 60–80% relative humidity. After 7 days, germination percentages were recorded. All experiments were conducted in duplicate. Data were processed using the formulas described in section 2.5.1.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the InfoStat statistical software, 2020 version (FCA, National University of Córdoba, Argentina) [33]. The in vitro plant growth promotion data were analyzed using Tukey’s multiple comparison test. Toxicological study results were expressed as mean ± SEM (standard error of the mean). Experimental groups were compared to the control group using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test. A p-value of less than 0.05 (p < 0.05) was considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 In vitro assays for plant growth-promoting traits

3.1.1 Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production

k. radicincitans bSL2 produced the highest concentration of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) at 48 h of culture, reaching 32.97 µg/mL. As incubation time increased, IAA production declined, with values of 26.05 µg/mL at 96 h and 12.6 µg/mL at 120 h.

3.1.2 Nitrogen fixation

- k. radicincitans bSL2 exhibited growth on specific media (NFb and LGI), accompanied by a color change of the pH indicator, indicating atmospheric nitrogen assimilation and medium acidification due to ammonium ion formation.

3.1.3 Phosphate solubilization

- k. radicincitans bSL2 demonstrated phosphate-solubilizing ability, as evidenced by clear halos around colonies on solid medium. The phosphate solubilization index (PSI), calculated as the ratio of the total halo diameter (including the colony) to the colony diameter (both in mm), showed an average value of 1.83 mm.

3.1.4 Siderophore production

The results did not show significant differences compared with those reported by Lambrese et al. [14]. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

3.2 Biomass production of K. radicincitans bSL2 in a cost-effective culture medium

In the comparative analysis, the commercial medium (YGM) yielded 5.8 × 108 CFU/mL at 24 h, while the low-cost medium (LCM) produced 2.3 × 108 CFU/mL, with no significant differences (p > 0.05). This demonstrates that sufficient biomass can be obtained for biostimulant formulation while reducing large-scale production costs. The biomass generated in LCM was used for subsequent assays on the effect of K. radicincitans bSL2 on L. sativa seed germination.

3.3 Seed germination assays under laboratory conditions

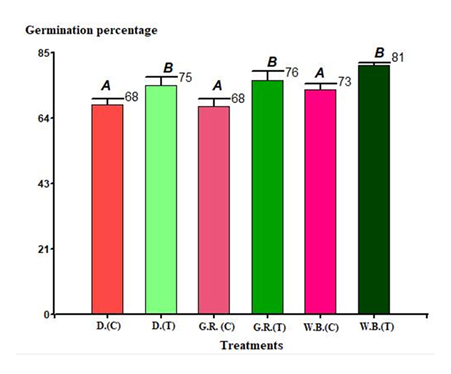

a. In trials with Lactuca sativa var. Capitata L., subtype Divina, seeds treated with the biostimulant containing K. radicincitans bSL2 reached an average germination rate of 74.5%, representing a 9.5% improvement compared to the negative control. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05) Figure 1.

b. In assays with L. sativa var. Capitata L., subtype Grand Rapids, seeds treated with K. radicincitans bSL2 showed an average germination rate of 76%, corresponding to a 10.2% improvement compared to the negative control. However, this difference was not statistically significant (p > 0.05) Figure 1.

c. In assays with L. sativa var. White Boston, seeds treated with K. radicincitans bSL2 exhibited an average germination rate of 70%, representing a 10.9% increase compared with the negative control. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05) Figure 1.

Figure 1: Seeds of L. sativa germinated under laboratory conditions, variety Capitata: D(C): Divina subtype, control; D(T): treated with a suspension of Kosakonia radicincitans bSL2; G.R.(C): Grand Rapid subtype, control; G.R.(T): treated with a suspension of K. radicincitans bSL2; W.B.(C): White Boston variety, control; W.B.(T): treated with a suspension of K. radicincitans bSL2. Means with a common letter do not show significant differences* (p > 0.05).

3.4 Seed germination assays under nursery conditions

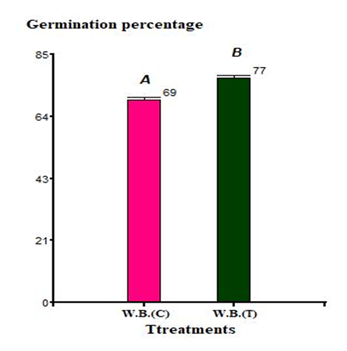

Since no statistically significant differences were observed among lettuce varieties in laboratory trials, nursery experiments were conducted only with L. sativa White Boston, a variety routinely used at IMPROFOP San Luis. Seeds treated with the biostimulant containing K. radicincitans bSL2 achieved an average germination rate of 77%, representing a 10.7% improvement compared with the negative control. This difference was statistically significant (p < 0.05) Figure 2.

3.5 Acute oral toxicity study

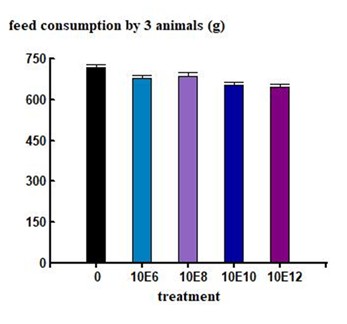

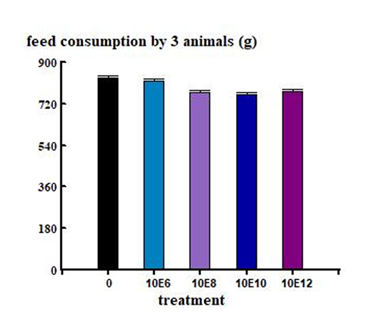

The acute oral toxicity study demonstrated that a single oral dose of K. radicincitans bSL2 at the tested concentrations did not cause mortality or visible signs of toxicity in either male or female Wistar rats. No signs of restlessness, respiratory depression, convulsions, or death were observed. No statistically significant differences were recorded in total body weight gain or food consumption between groups throughout the trial (Figure 3, 4).

Statistical analysis indicated that treatment did not significantly alter the relative weight of the examined organs. No changes were observed in clinical appearance, behavior, or neurological function according to Irwin’s test parameters (Table 1).

Gross examination of organs (heart, liver, stomach, intestine, lungs, kidneys, spleen, testes, or ovaries) from animals treated with different concentrations of K. radicincitans bSL2 revealed no abnormalities, and no adverse morphological changes attributable to oral administration were detected. Statistical analysis confirmed no significant differences [F (2,8) = 6.132, 1.617, 0.7305, 0.4648, 2.865, and 0.080, respectively, for spleen, heart, lung, liver, kidney, and ovary; all p = n.s.] in the relative weight of these organs in female Wistar rats compared with controls (Table 2). Similarly, no significant differences were found in male rats [F (2,8) = 1.000, 2.837, 2.384, 5.241, 1.020, and 1.138, respectively, for spleen, heart, lung, liver, kidney, and testes; all p = n.s.] compared with negative controls. Table 3.

|

Toxicity parameters |

Negative control |

Experimental groups |

|

(saline solution) |

(Increasing doses of K. r.) |

|

|

Excitation |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Tremors |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Involuntary contractions |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Motor activity |

Normal |

Normal |

|

Respiratory changes |

Normal |

Normal |

|

Diarrhea |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Aggressiveness |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Passivity |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Scratching |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Piloerection |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Salivation |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Lacrimation |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Palpebral ptosis |

Negative |

Negative |

|

Ears(cyanosis, hyperemia) |

Negative |

Negative |

Table 1: Irwin's toxicity parameters in rats exposed to varying concentrations of K. radicincitans bSL2 in saline solution

|

Treatments |

Spleen |

Heart |

Lung |

Liver |

Kidney |

Ovary |

|

Control |

0,18 ±0.01 |

0,34 ±0.01 |

0,56 ±0.10 |

5.14 ±0.31 |

1.18 ±0.02 |

0.02 ± 0.01 |

|

106 UFC/mL |

0.19 ±0.01 |

0.37 ±0.01 |

0.70 ±0.05 |

5.02 ±0.35 |

1.13 ±0.01 |

0.02 ± 0.01 |

|

108 UFC/mL |

0.17 ±0.01 |

0.40 ±0.03 |

0.60 ±0.03 |

5.44 ±0.34 |

1.12 ±0.01 |

0.03 ± 0.01 |

|

1010 UFC/mL |

0.20 ±0.01 |

0.37 ±0.02 |

0.67 ±0.04 |

5.27 ±0.10 |

1.18 ±0.02 |

0.02 ± 0.01 |

|

1012 UFC/mL |

0.19 ± 0.01 |

0.40 ± 0.02 |

0.63 ± 0.05 |

5.66 ± 0.52 |

1.15 ± 0.04 |

0.03 ± 0.01 |

|

†References: UFC: Colony Forming Units |

||||||

Table 2: Mean ± S.E.M. of relative organ weight (%) in female Wistar rats exposed to different concentrations of K. radicincitans bSL2 orally.

|

Treatments |

Spleen |

Heart |

Lung |

Liver |

Kidney |

Testicle |

|

Control |

0,20 ± 0.01 |

0,38 ± 0.01 |

0,75 ± 0.07 |

6.30 ± 0.44 |

1.25 ± 0.05 |

0.96 ± 0.04 |

|

106 UFC/mL. |

0.19 ± 0.02 |

0.43 ± 0.04 |

0.69 ± 0.06 |

6.88 ± 0.17 |

1.32 ± 0.05 |

0.89 ± 0.07 |

|

108 UFC/mL. |

0.19 ± 0.01 |

0.42 ± 0.02 |

0.68 ± 0.01 |

5.70 ± 0.36 |

1.19 ± 0.03 |

0.77 ± 0.01 |

|

1010 UFC/mL. |

0.19 ± 0.01 |

0.35 ± 0.01 |

0.54 ± 0.04 |

5.74 ± 0.25 |

1.13 ± 0.02 |

1.01 ± 0.04 |

|

1012 UFC/mL. |

0.21 ± 0.01 |

0.36 ± 0.01 |

0.65 ± 0.02 |

6.58 ± 0.16 |

1.23 ± 0.03 |

1.04 ± 0.01 |

† References: UFC: Colony Forming Units

Table 3: Mean ± S.E.M. of relative organ weight (%) in male Wistar rats exposed to different concentrations of K. radicincitans bSL2 orally.

4. Discussion

4.1 Indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production, nitrogen fixation, phosphate solubilization, and siderophore production

Similar findings were reported by Ali et al. [34], who isolated K. radicincitans from saline soils, obtaining an IAA production of 40.44 µg/mL. They also confirmed diazotrophic activity and phosphate solubilization in the bacterial isolate, supporting its potential as a PGPB in wheat under saline stress conditions. Mohammad et al. [35] recovered K. radicincitans KR-17 from the potato rhizosphere, demonstrating tolerance to high salt concentrations, IAA production, siderophore synthesis, and phosphate solubilization. Narayanan et al. [36] studied isolates from the rhizosphere of Arachis hypogaea L., identifying a Kosakonia sp. strain with the most promising traits, including IAA production, phosphate solubilization, and nitrogen fixation. Jan-Roblero et al. [16] reviewed studies highlighting nitrogen fixation as one of the main functional traits of K. radicincitans in agricultural applications.

The present results confirm that K. radicincitans bSL2 possesses multiple PGPB traits, supporting its candidacy for biostimulant development. Similar outcomes with other Kosakonia strains have been reported worldwide [16,20,21,34].

4.2 Biomass production in cost-effective culture medium

A low-cost medium (LCM) was formulated using by-products from a local craft brewery, including spent grain (residues from barley milling and mashing) and exhausted yeast after fermentation. Several studies have explored low-cost substrates for microbial biomass production, often using agro-industrial by-products. For instance, dos Santos et al. [12] summarized the use of soybean, beans, and corn as substrates; Romano et al. [37] produced Kosakonia pseudosacchari TL13 biomass using whey, exhausted yeast, molasses, and vinasse; Lobo et al. [38] compiled the use of glycerol, molasses, whey, and different flours; and Vassileva et al. [39] investigated diverse agro-waste for fungal cultivation. More unconventional resources, such as cladode juice from Opuntia ficus pruning, have also been proposed for microbial biomass production [40].

4.3 Seed germination under laboratory conditions

The results demonstrated that K. radicincitans bSL2 significantly enhanced lettuce seed germination, regardless of the variety evaluated. These findings are consistent with those of Jeephet et al. [41], who reported that seed pelleting combined with plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB), specifically Enterobacter sp., increased germination by 14% under greenhouse conditions compared with untreated seeds. Under laboratory conditions, the improvement was more modest, with an increase of approximately 6%.

4.4 Seed germination under nursery conditions

Although no studies have yet reported K. radicincitans as a biostimulant for lettuce germination, several works document its role in other crops. For example, K. radicincitans KR-17 improved radish germination and growth parameters under salinity stress [35]. Likewise, PGPB consortia applied to Daucus carota L. (carrot) seeds improved plant growth and soil fertility [42,43] also demonstrated enhanced growth in kale seeds treated with PGPB under greenhouse conditions.

4.5 Acute oral toxicity

Despite interspecies differences, well-designed preclinical toxicological assays in laboratory animals have proven to be reliable predictive models for humans [44]. Acute toxicity studies are essential to classify substances and provide initial insights into their toxic mode of action [45]. These assays assess the toxic potential of a product following single or repeated doses within 24 h. High-dose exposures in animals remain a necessary approach to identify potential risks for humans exposed to lower levels [46]. Variations in behavior and body weight are commonly used as objective indicators of toxicity, with significant deviations in weight gain considered early signs of adverse effects [47-49]. In this study, K. radicincitans bSL2 did not induce any such effects, supporting its safety under the tested conditions [50-53].

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated that the K. radicincitans bSL2 strain, isolated from apples in San Luis Province, Argentina, exhibits plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) traits including nitrogen fixation, inorganic phosphate solubilization, indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production, and siderophore synthesis. Additionally, biomass production of this strain was successfully achieved at high yields using a cost-effective culture medium formulated from local industry waste, providing an economical alternative that could facilitate large-scale production for bioinput development. Application of K. radicincitans bSL2 on seeds of various Lactuca sativa varieties resulted in a significant increase in germination rates under both laboratory and nursery conditions. This finding is particularly noteworthy, as although PGPB use to enhance seed germination has been reported, there are limited studies in lettuce, and no previous reports specifically employing Kosakonia species for this purpose. Finally, acute oral toxicity assays in Wistar rats revealed no relevant toxic effects in either females or males. To our knowledge, there are no prior toxicological studies reported for Kosakonia strains evaluated as PGPB.

Taken together, these results provide valuable evidence supporting the use of the native strain K. radicincitans bSL2 as an active component in biostimulant formulations for horticultural crops. This also represents the first local report of a Kosakonia strain exhibiting such properties.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the National University of San Luis, Argentina. We also gratefully acknowledge the technical assistance and support of Technician Flavia Silvina Guiñez.

Financing

This study was funded by the National University of San Luis through PROICO 2–0520 “Development of bioinputs for the agri-food sector.” Ethical standards were met and technical specifications for the production, care and use of laboratory animals. IMPROFOP Nursery (sapem) collaborated with material (agreement RR 857/2024).

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability

The dataset generated and/or analyzed during the study process is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- FAO, IFAD, WHO, et al. State of food security and nutrition in the world 2023. FAO (2023).

- Aramendis RH, Mondaini AO, Rodríguez AG. Agricultural bioinputs: Situation and outlook in Latin America and the Caribbean. ECLAC Project Documents (2023).

- Bashan Y, de-Bashan LE, Prabhu SR, et al. Advances in bacterial inoculant technology for promoting plant growth. Plant and Soil 378 (2014): 1-33.

- Singh SK. Sustainable agriculture: Biofertilizers under stress. International Journal of Plant, Animal and Environmental Sciences 10 (2020): 158-178.

- Fanai A, Bohia B, Lalremruati F, et al. Plant adaptations induced by PGPB. PeerJ 12 (2024): e17882.

- Timofeeva AM, Galyamova MR, Sedykh SE. Phytohormone-mediated stress regulation by PGPB. Plants 13 (2024): 2371.

- Esquivel-Cote R, Gavilanes-Ruiz M, Cruz-Ortega R, et al. ACC deaminase in rhizobacteria. Revista Fitotecnia Mexicana 36 (2013): 251-258.

- Oleńska E, Małek W, Wójcik M, et al. PGPB in challenging conditions. Science of the Total Environment 743 (2020): 140682.

- Benjumeda Muñoz D. Plant growth-promoting bacteria: Mechanisms and applications. University of Seville (2017).

- Khoso MA, Wagan S, Alam I, et al. PGPR effects on plant nutrition. Plant Stress 11 (2023): 100341.

- Uthayasooriyan M, Pathmanathan S, Ravimannan N, et al. Alternative culture media formulation. Der Pharmacia Lettre 8 (2016): 431-436.

- Dos Santos FP, et al. Alternative culture media from vegetable products. Food Science and Technology 42 (2022): e00621.

- Resolution 1004/2023. Ministry of Agriculture and Livestock (2023).

- Lambrese Y, Guiñez M, Calvente V, et al. Siderophore production by Kosakonia. Bioresource Technology Reports 3 (2018): 82-87.

- Brady C, Cleenwerck I, Venter S, et al. Taxonomic evaluation of Enterobacter. Systematic and Applied Microbiology 36 (2013): 309-319.

- Jan-Roblero J, Cruz Maya JA, Barajas CG. Kosakonia. In: Beneficial Microbes in Agro-Ecology (2020): 213-231.

- Mertschnigg T, Patz S, Becker M, et al. Kosakonia radicincitans bacteremia in Europe. Scientific Reports 10 (2020): 1948.

- Navarta LG, Calvo J, Posetto P, et al. Freeze-drying of microbial mixtures. SN Applied Sciences 2 (2020): 1-8.

- Berger B, Wiesner M, Brock AK, et al. Kosakonia radicincitans promotes radish growth. Agronomy for Sustainable Development 35 (2015): 1521-1528.

- Bergottini VM, Otegui MB, Sosa DA, et al. Bio-inoculation of Ilex paraguariensis Biology and Fertility of Soils 51 (2015): 749-755.

- Berger B, Baldermann S, Ruppel S. Kosakonia radicincitans improves fruit yield of tomato. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 97 (2017): 4865-4871.

- Berger B, Patz S, Ruppel S, et al. Formulation and application of Kosakonia radicincitans in maize. BioMed Research International 2018 (2018): 1-9.

- Becker M, Patz S, Becker Y, et al. Comparative genomics of Kosakonia radicinc Frontiers in Microbiology 9 (2018): 1997.

- Bhatti MD, Kalia A, Sahasrabhojane P, et al. Kosakonia radicincitans causing bloodstream infection. Frontiers in Microbiology 8 (2017): 62.

- Serrano López LÁ, Angulo Castro A, Ayala Tafoya F, et al. IAA-producing bacteria from Sinaloa. In: Advances in Sustainable Agriculture (2024): 941.

- Argüello-Navarro AZ, Madiedo Soler N, Moreno-Rozo LY. Quantification of diazotrophic bacteria isolated from cocoa soils using the MPN technique. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Agrícolas 7 (2016): 1470-1482.

- Tejera-Hernández B, Heydrich-Pérez M, Rojas-Badía MM. Phosphate-solubilizing Bacillus. Agronomía Mesoamericana 24 (2013): 357-364.

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. Acute oral toxicity guideline 423. OECD (2001).

- Argentine National Administration of Drugs, Food and Medical Technology (ANMAT). Disposition No. 9236/2023. Buenos Aires (2023).

- Irwin S. Comprehensive observational assessment in mice. Psychopharmacologia 13 (1968): 222-257.

- Ortega Markman BE, Bacchi EM, Myiake Kato ET. Antiulcerogenic effects of Campomanesia. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 94 (2004): 55-57.

- International Seed Testing Association. International Rules for Seed Testing. Seed Science and Technology 31 (2023): Supplement.

- InfoStat Group. InfoStat software, version 2020. National University of Córdoba (2020).

- Ali AA, El-Kholy AS. Isolation and characterization of endophytic Kosakonia radicincitans to stimulate wheat growth in saline soil. Journal of Advances in Microbiology 22 (2022): 115-126.

- Mohammad Shahid F, Al-Khattaf MD, Zeyad MT, et al. Salt tolerance induced by Kosakonia. Frontiers in Plant Science 13 (2022): 919696.

- Narayanan M, Pugazhendhi A, David S, et al. Kosakonia effects on peanut growth. Agronomy 12 (2022): 1801.

- Romano I, Ventorino V, Ambrosino P, et al. Eco-sustainable biostimulant with Kosakonia. Frontiers in Microbiology 11 (2020): 2044.

- Lobo CB, Juárez Tomás MS, Viruel E, et al. Low-cost PGPB formulations. Microbiological Research 219 (2019): 12-25.

- Vassileva M, Mocali S, Martos V, et al. Plant beneficial microorganisms research advances. Preprints (2024): 0286.

- Magarelli RA, Trupo M, Ambrico A, et al. Waste-based media for PGP microorganisms. Fermentation 8 (2022): 225.

- Jeephet P, Thawong N, Atnaseo C, et al. PGPB application in lettuce pelleting. Journal of Environment and Natural Resources 22 (2024): 26-33.

- Pellegrini M, Pagnani G, Rossi M, et al. Bacterial consortium in carrot. Applied Sciences 11 (2021): 3274.

- Helaly AA, Mady E, Salem EA, et al. Effects of PGPB on kale. Journal of Plant Nutrition 45 (2022): 2465-2477.

- Gad SC. Animal Models in Toxicology. CRC Press (2006).

- Balogun SO, da Silva Jr IF, Colodel EM, et al. Toxicological evaluation of hydroethanolic extract of Helicteres sacarolha. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 157 (2014): 285-291.

- Erickson MA, Penning TM. Drug toxicity and poisoning. In: Goodman & Gilman’s Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics 13 (2019): 55-64.

- Liju VB, Jeena K, Kuttan R. Toxicity evaluation of turmeric oil. Food and Chemical Toxicology 53 (2013): 52-61.

- Sireeratawong S, Lertprasertsuke N, Srisawat U, et al. Toxicity of Sida rhombifolia. Songklanakarin Journal of Science and Technology 30 (2008): 729-737.

- da Silva Oliveira GL, Medeiros SC, Sousa AML, et al. Preclinical toxicology of garcinielliptone FC. Phytomedicine 23 (2016): 477-482.

- Ashafa AOT, Yakubu MT, Grierson DS, et al. Toxicological evaluation of the aqueous extract of Felicia muricata leaves in Wistar rats. African Journal of Biotechnology 8 (2009): 949-954.

- Moore KL, Dalley AF, Agur AMR. Clinically Oriented Anatomy. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins (2014).

- Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries. Lettuce production report 2023. Ministry of Economy (2023).

- Shokryazdan P, Faseleh Jahromi M, Liang JB, et al. Safety assessment of probiotics. PLoS One 11 (2016): e0159851.

Impact Factor: * 4.1

Impact Factor: * 4.1 Acceptance Rate: 75.32%

Acceptance Rate: 75.32%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks