A Modified Transfemoral Approach at the Site of Septic Total Hip Arthroplasty Revisions

Konstantinos Anagnostakos1,2* and Ismail Sahan2

1Department of Joint Surgery and Sports Traumatology, Nardini Clinic, Zweibrücken, Germany

2Center for Orthopedics and Trauma Surgery, Saarbrücken Hospital, Saarbrücken, Germany

*Corresponding Author: Konstantinos Anagnostakos, Department of Joint Surgery and Sports Traumatology, Nardini Clinic, Zweibrücken, Germany.

Received: 06 November 2025; Accepted: 14 November 2025; Published: 18 November 2025

Article Information

Citation: Konstantinos Anagnostakos, Ismail Sahan. A Modified Transfemoral Approach at the Site of Septic Total Hip Arthroplasty Revisions. Journal of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine. 7 (2025): 516-526.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The surgical management of periprosthetic hip joint infections can be very demanding. 20 patients (22 joints) suffering from periprosthetic hip joint infections have been treated by means of a new transfemoral approach at the site of a two-stage procedure. There were eight female and 12 male patients at a mean age of 71.4 [54-86] years. Prosthesis reimplantation was performed in 17 patients (18 cases). At a mean follow-up of 43 [24-85] months 16/17 (94%) of the cases that underwent prosthesis reimplantation were free of any local or systemic infection signs. There was no case of a stem subsidence. All osteotomies showed a complete osseous consolidation three to six months after the first stage. The present technique has demonstrated very promising results at a high infection eradication rate.

Keywords

<p>Periprosthetic joint infection; Hip infection; Transfemoral approach; Femoral osteotomy</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Femoral stem revision can be challenging at the site of septic total hip arthroplasty (THA) revision, especially when well osseointegrated cementless stems, well-cemented stems, bone defects or large osteolytic areas are present. A sole revision through an endofemoral approach might lead to the emergence of fractures, incomplete cement removal or insufficient debridement [1-6].

To manage this problem, extensile surgical approaches have been described. The transfemoral approach, initially described by Wagner [1], and further modified by other authors [2-3] or the extended trochanteric osteotomy [4-6] allow for a good exposure of the femoral canal and removal of the prosthesis. However, these procedures might be still accompanied by intra- and postoperative complications, such as intraoperative fractures or incomplete osseous consolidation of the osteotomized bone flap [1-6].

Here, we would like to report on our experience with a new modified transfemoral approach at the site of septic THA revisions.

2. Materials-Methods

Between January 2017 and December 2021, a total of 67 consecutive patients with late hip PJIs have been treated in our department by means of a two-stage procedure. In 20 of these 67 cases (30%), a transfemoral approach was utilized for removal of the femoral stem. Indications for the transfemoral approach were 1) well-fixed cementless stems that could not be removed endofemoral, 2) cemented stems with large osteolyses and hence higher risk of an intraoperative fracture during cement removal and osteolyses debridement, and 3) cemented stems with a well-fixed cement mantle, especially in the distal part, that could not be completely removed through an endofemoral approach without increasing the risk of an intraoperative fracture.

As previously described [7], all patients were treated according to an identical algorithm. The infection was defined by the criteria of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) [8]. Preoperatively, a joint aspiration was performed to differentiate between aseptic from septic prosthesis loosening, except for patients who had confirmed hematogenous infections by positive blood cultures or those who came with systemic sepsis signs and were immediately operated. A further exemption regarded patients who had fistulas. In these cases, we preferred to take directly tissue samples during surgery. If the joint aspiration revealed negative microbiological findings, but clinical, laboratory and/or radiological findings were still highly suspicious for the presence of an infection, an arthroscopic or open biopsy was performed prior to the prosthesis revision.

All cases were treated by a two-stage procedure. In the first surgery, all prosthetic components including cement were removed, and all infected, necrotic or ischemic tissue layers were debrided. A pulsatile lavage with at least 5l Ringer solution was always performed. Tissue samples from at least five different locations along with joint fluid were taken and sent for further microbiological and histological examination. Until 2018, all samples were cultured over seven days. Since 2019, the culture period was extended to 14 days because some bacteria can be only detected after prolonged culture [9]. Regarding the histological findings, all samples were classified in accordance with the system of Krenn and Morawietz [10]. For cases with negative culture but positive histological findings, the samples were further investigated by means of a broad-range 16S rRNA polymerase chain reaction.

2.1 Transfemoral approach - surgical technique

The technique is described based on the intraoperatively taken photos of patient no. 16.

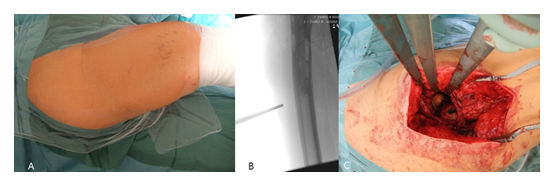

All patients were placed in lateral position (Figure 1A). Under fluoroscopic control, the length of the skin incision was determined (Figure 1B). After transection of the skin and subcutis, the fascia lata was split in line with the skin incision. A standard transgluteal approach according to Bauer was utilized (Figure 1C).

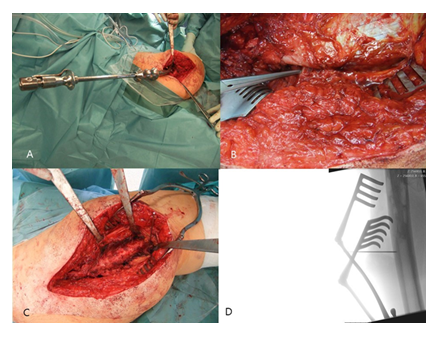

After capsulotomy and stem dislocation, the leg was placed into the four position. The cone region was debrided, and the cement around the proximal part of the stem could be removed by thin osteotomes. A universal extractor was routinely used for stem removal, which usually occurred easily in the cemented cases (Figure 2A).

Figure 2: A: Removal of the stem with a universal extractor.; B: Identification of the proximal dorsal border of the M. vastus lateralis at its insertion, immediately anterior to the tendon of the M. gluteus maximus,; C: Medial retraction of the M. vastus lateralis by Hohmann retractors.; D: Determination of the length of the femur osteotomy.

Following stem removal, the leg was placed back to the original position. Then, the proximal dorsal border of the M. vastus lateralis was identified at its origin on the Tuberculum innominatum, immediately anterior to the tendon of the M. gluteus maximus (Figure 2B). Using a diathermy knife, the dorsal border of the M. vastus lateralis was detached from the lateral intermuscular septum until distally. Perforated vessels were identified and ligated. Then, the musculature was retracted anteriorly with a rasparatory, and Hohmann elevators were inserted for medial retraction (Figure 2C). Under fluoroscopic control, the length of the femur osteotomy was determined. The femur osteotomy should end immediately below the distal part of the cement or the stem tip (Figure 2D).

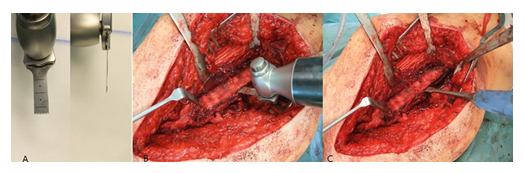

For the oscillating osteotomy, a blade sized 35x10x0.8mm (Fa. SMS medipool AG, Friedrichstal, Germany) was used (Figure 3A). The dorsal border of the osteotomy was the Linea aspera. For prevention of an intraoperative fracture, the width of the osteotomy should not exceed one third of the femoral circumference. Special attention should be paid that the osteotomy occurs convergent to the femur level (Figure 3B), which allows for an excellent re-adaptation of the bone flap later. After completion of the osteotomy, the femur could be carefully opened with a thin osteotome (Figure 3C).

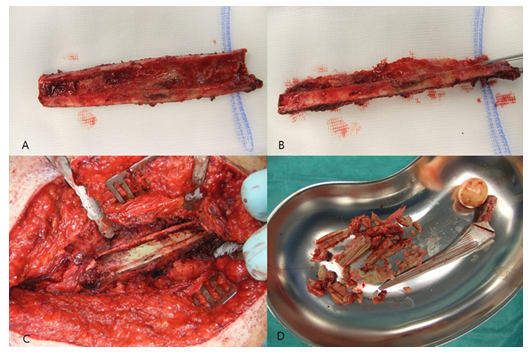

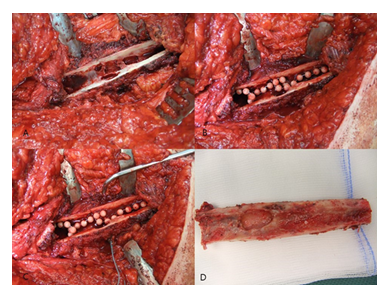

Following exposure of the underlying cement mantle and/or medullary canal, the debridement could be proceeded. After removal of all cement particles and thorough debridement of osteolytic areas (Figure 4A-D), a pulsatile lavage was performed.

Figure 6: A: Placement of the bone flap – no bone step is evident if the osteotomy is technically done correct.; B: Secure with 3 non-absorbable sutures.; C: Reattachment of the M. vastus lateralis – no signs of any damage of the muscle structure.; D: Postoperative X-rays of the right hip joint with the Girdlestone procedure – no dislocation of the osteotomy.

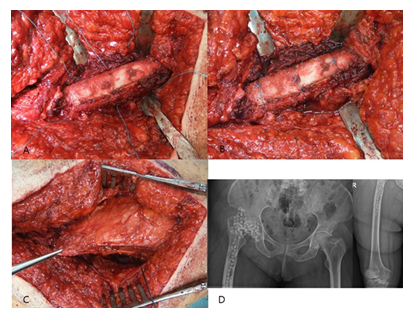

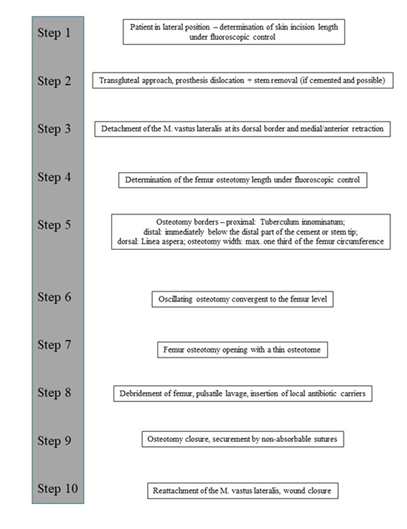

A commercially available, gentamicin-loaded bead (Septopal®, Fa. ZimmerBiomet, Germany) was routinely inserted into the femur canal (Figure 5A-D) and two additional into the acetabulum cavity. We decided to perform a Girdlestone procedure instead of a spacer implantation in all cases in order to prevent any possible mechanical complications (especially femur fractures) that might occur if patients put partial or full weight-bearing onto the operated leg. The bone flap was then placed back after it had been thoroughly debrided from soft-tissues, periprosthetic membrane and cement particles. If the osteotomy had been done technically correct, no bone step was evident. The osteotomy was then secured by three non-absorbable sutures (Ethibond Excel 2-0, Fa. Ethicon) (Figure 6A-B). The M. vastus lateralis was reattached (Figure 6C), and the wound was closed in layers. X-rays of the operated region were routinely performed in the 5th postoperative day (Figure 6D). All technique steps are summarized in Figure 7.

2.2 Postoperative regimen

Postoperatively, an immediate systemic antibiotic therapy was started; either specific, if the causative organism was preoperatively known, or a calculated therapy with 1.5 g cefuroxime intravenously, if the causative organism was unknown, and adjusted, if necessary, during the further course. All patients received an antibiotic therapy over 6 weeks, consisting of 3-4 weeks intravenously and 2-3 weeks orally. All patients were allowed to walk on crutches under no weight-bearing of the operated extremity.

Six weeks after the first procedure, the antibiotic therapy was paused for 7-10 days and the serum inflammation parameters (C-reactive protein, blood cell count) controlled. If the laboratory parameters were normal, the prosthesis reimplantation was then planned, if the wound had healed and the general medical condition of the patient allowed for it. The type of implants used were chosen based on the amount of bone loss and quality. A joint aspiration was not routinely carried out prior to spacer explantation and prosthesis reimplantation, because literature data has demonstrated no benefit of such a measure [11-12].

At reimplantation, soft-tissue specimens were taken again and sent for microbiological and histopathological examination. At macroscopical presence of pus or other tissue signs that might have been suspicious for persistence of infection, the joint was debrided again and the beads only exchanged. All patients that underwent prosthesis reimplantation did not receive postoperatively any systemic antibiotic therapy.

As “persistence of infection” were defined those cases that showed an infection with the same pathogen organism as primarily identified. As “reinfection” were defined those cases that suffered from an infection with a different organism than primarily detected. “Treatment failure” was defined only by persistence of infection.

2.3 Radiological evaluation

The osteotomy site was considered to have been healed if callus was seen bridging the site in both the anterio-posterior and lateral radiographs [5-6]. Vertical subsidence of the femoral component was measured as the change in the distance from the inferior margin of the component neck to the most proximal point on the lesser trochanter and from the proximal lateral end of the component body to the tip of the greater trochanter [13-15]. Significant subsidence was defined as being >5 mm [16-17].

3. Results

There were eight female and 12 male patients at a mean age of 71.4 [54-86] years. One female and one male patient suffered from a bilateral hip PJI, respectively. Demographic data and comorbidities of the patients are summarized in Table 1.

|

Patient |

Gender |

Age [years] |

Comorbidities |

|

1 |

m |

86 |

none |

|

2 |

m |

56 |

none |

|

3 |

m |

54 |

arterial hypertension, NIDDM |

|

4 |

f |

69 |

hypothyreosis, lung cancer, peripheral arterial obstructive diesease IIb |

|

5* |

f |

72 |

obesity, arterial hypertension, hypothyreosis, IDDM, atrial fibrillation |

|

6 |

f |

76 |

arterial hypertension, bronchial asthma, renal insufficiency, carotis stenosis |

|

7 |

f |

76 |

atrial fibrillation, hypothyreosis, colon cancer, aortic valve stenosis |

|

8 |

m |

56 |

arterial hypertension, ghout, NIDDM, coronary heart disease, generalised lymphadenopathy |

|

9 |

f |

65 |

obesity, arterial hypertension |

|

10 |

m |

82 |

none |

|

11 |

f |

82 |

arterial hypertension, COPD, atrial fibrillation, renal insufficiency |

|

12 |

m |

80 |

arterial hypertension, atrial fibrillation, gastric ulcer, pulmonal hypertension, hemicolectomy |

|

13 |

m |

77 |

NIDDM, renal insufficiency, myocardial infarction, arterial hypertension |

|

14* |

m |

54 |

heart insufficiency, renal dialysis, lung fibrosis, arterial hypertension, selective IgM deficiency |

|

15 |

m |

72 |

arterial hypertension |

|

16 |

f |

76 |

none |

|

17 |

m |

77 |

stroke, pacemaker, gastritis, coronary heart disease, arterial hypertension |

|

18 |

m |

85 |

arterial hypertension |

|

19 |

f |

75 |

NIDDM, arterial hypertension, hypothyreosis |

|

20 |

m |

58 |

arterial hypertension, ghout, NIDDM, morbid obesity |

*No. 5 and 14: bilateral cases; m: male; f: female; NIDDM: non insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; IDDM: insulin dependent diabetes mellitus; COPD: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Table 1: Demographic data and comorbidities of the 20 patients who were treated with the modified transfemoral approach.

The primary surgical procedure was a THA in 17 cases and a hemiarthroplasty in five cases (Figure 8).

The duration between the primary surgery and manifestation of the infection varied between 8 months and 14 years. The preoperative examination of the serum inflammation parameters showed clearly elevated values in the majority of the cases. Methicillin-susceptible and –resistant S. epidermidis and S. aureus, respectively, were responsible for approximately half of the cases. In three cases the microbiological findings were negative at positive histopathological results. The histopathological examination revealed infectious membranes (type II and III) in 82% (18/22) cases. All data are summarized in Table 2.

|

Patient |

Prosthesis type |

CRP [mg/l] |

WBC count [/106] |

Causative organism |

Periprosthetic membrane type |

|

1 |

cemented hemiarthroplasty |

310 |

5,900 |

MRSA |

II |

|

2 |

cementless THA |

27 |

14,700 |

P. micra, S. capitis |

III |

|

3 |

cementless THA |

8.5 |

8,400 |

MRSE |

III |

|

4 |

cemented THA |

7.2 |

9,000 |

E. faecium |

I |

|

5 (1) |

cementless THA |

346 |

8,800 |

MSSA |

II |

|

5 (2) |

cementless THA |

84 |

6,500 |

MSSA |

II |

|

6 |

cemented hemiarthroplasty |

8.4 |

6,600 |

negative |

II |

|

7 |

cemented hemiarthroplasty |

57.9 |

5,400 |

negative |

III |

|

8 |

cementless THA |

13.1 |

5,500 |

P. micra |

II |

|

9 |

cemented THA |

26.4 |

9,800 |

F. magna, MSSE, E. coli |

II |

|

10 |

hybrid THA |

29.2 |

6,500 |

MRSE |

III |

|

11 |

cementless THA |

15.4 |

11,900 |

viridans streptococci |

II |

|

12 |

cementless THA |

128 |

6,700 |

MRSE |

II |

|

13 |

cementless THA |

43 |

8,800 |

Ps. aeruginosa |

III |

|

14 (1) |

cementless THA |

75.7 |

5,800 |

E. faecalis |

IV |

|

14 (2) |

cementless THA |

72.5 |

11,200 |

E. faecalis |

IV |

|

15 |

cementless THA |

14.8 |

7100 |

MSSA |

II |

|

16 |

hybrid THA |

< 2 |

7,400 |

negative |

II |

|

17 |

cementless hemiarthroplasty |

117 |

7,300 |

MRSE |

IV |

|

18 |

cemented hemiarthroplasty |

8,3 |

11,400 |

MSSE, C. albicans |

II |

|

19 |

cementless THA |

109 |

21,800 |

K. pneumoniae |

II |

|

20 |

cementless THA |

51.1 |

13,400 |

S. capitis |

II |

CRP: C-reactive protein; WBC: white blood cell; THA: total hip arthroplasty; MRSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MSSA: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; MRSE: methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus epidermidis: MSSE: methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus epidermidis.

Table 2: Data about implant type, and preoperative laboratory information and microbiological findings.

2.4 First stage – between stages

The mean surgery time was 123 [78-209] minutes. No technical complications and especially no intraoperative fractures occurred during the first stage.

14 patients did not suffer from any complications at all between stages. One patient did not present for prosthesis reimplantation, and another one passed away due to pneumonia 3 weeks after the surgery. Two cases had to be surgically revised due to prolonged drain; in both cases the microbiological findings were negative. One patient suffered from a Covid-19 infection. In three cases, a proximal femur/ greater trochanter fracture was observed after dismissal of the patients, respectively. All fractures occurred because these patients put weight-bearing onto the operated extremity and fell. All information about the first stage and the complications between stages are summarized in Table 3.

|

Patient |

Surgery time first stage [min] |

Osteotomy Length [mm] |

Time period between stages [days] |

Complications between stages |

|

1 |

98 |

87 |

82 |

none |

|

2 |

173 |

97 |

72 |

none |

|

3 |

100 |

75 |

48 |

none |

|

4 |

96 |

113 |

14 |

none |

|

5 (1) |

133 |

130 |

unknown |

unclear |

|

5 (2) |

148 |

139 |

unknown |

unclear |

|

6 |

78 |

60 |

58 |

none |

|

7 |

107 |

137 |

90 |

none |

|

8 |

147 |

117 |

57 |

none |

|

9 |

106 |

101 |

97 |

none |

|

10 |

102 |

102 |

70 |

none |

|

11 |

186 |

181 |

95 |

Covid-19 infection |

|

12 |

82 |

115 |

57 |

none |

|

13 |

91 |

122 |

n.r. |

exitus due to pneumonia |

|

14 (1) |

111 |

130 |

91 |

2x revision due to prolonged drain; prox. femur fracture |

|

14 (2) |

117 |

108 |

216 |

prox. femur fracture |

|

15 |

141 |

114 |

58 |

none |

|

16 |

126 |

130 |

46 |

none |

|

17 |

105 |

75 |

120 |

greater trochanter fracture |

|

18 |

117 |

57 |

n.r. |

revision after 10 days due to prolonged drain |

|

19 |

149 |

148 |

78 |

none |

|

20 |

209 |

123 |

62 |

none |

n.r.: not relevant

Table 3: Data about the first stage of the treatment.

2.5 Second stage

Prosthesis reimplantation was performed in 17 patients (18 cases). One patient decided to retain the Girdlestone situation as a definitive solution. At the time of the second stage, elevated serum inflammation parameters were evident in 5/18 cases (27%) (Table 4).

|

Patient |

Preop. CRP [mg/l] |

Preop. WBC count [/106] |

Surgery time [min] |

Implant type |

Microbiological findings |

Complications |

Follow-up [months] |

|

1 |

4.5 |

6,500 |

102 |

press-fit cup + modular stem |

negative |

none |

73 |

|

2 |

5.2 |

9,100 |

138 |

press-fit cup + modular stem |

negative |

none |

63 |

|

3 |

< 2.0 |

7,000 |

155 |

anti-protrusio cage + modular stem |

negative |

none |

60 |

|

4 |

8.8 |

8,000 |

177 |

anti-protrusio cage + modular stem |

negative |

intraop. Tr. major-fracture; prosthesis dislocation after 34 months, closed reduction |

49 |

|

5 (1) |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

lost |

|

5 (2) |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

unclear |

lost |

|

6 |

4.3 |

5,600 |

95 |

bipolar head + modular stem |

negative |

peroneal lesion |

43 |

|

7 |

34.1 |

6,000 |

188 |

anti-protrusio cage + modular stem |

E. faecalis |

cardiopulmonal decompensation |

42 |

|

8 |

2.3 |

5,000 |

186 |

press-fit cup + modular stem |

negative |

none |

31 |

|

9 |

2.5 |

8,500 |

189 |

anti-protrusio cage + modular stem |

MRSE |

reinfection (MRSE, C. koseri/diversus, C. albicans), permanent resection arthroplasty |

27 |

|

10 |

7.9 |

5,400 |

84 |

press-fit cup + modular stem |

negative |

none |

26 |

|

11 |

10.0 |

7,600 |

238 |

anti-protrusio cage + modular stem |

negative |

pulmonary decompensation with pneumothorax right |

24 |

|

12 |

5.6 |

8,700 |

124 |

press-fit cup + modular stem |

negative |

none |

21 |

|

13 |

n.r. |

n.r. |

n.r. |

n.r. |

n.r. |

n.r. |

exitus |

|

14 (1) |

92.9 |

6,000 |

165 |

anti-protrusio cage + proximal femur replacement |

negative |

pneumonia |

19 |

|

14 (2) |

58.1 |

6,300 |

198 |

anti-protrusio cage + proximal femur replacement |

negative |

none |

15 |

|

15 |

< 2 |

7,700 |

121 |

press-fit cup + modular stem |

negative |

none |

16 |

|

16 |

< 2 |

13,100 |

122 |

press-fit cup + modular stem |

negative |

none |

15 |

|

17 |

8 |

4,500 |

176 |

cemented constrained liner + proximal femur replacement |

negative |

exitus due to pneumonia after 5 months |

5 |

|

18 |

n.r. |

n.r. |

n.r. |

permanent Girdlestone |

n.r. |

n.r. |

13 |

|

19 |

12.2 |

11,000 |

140 |

press-fit cup + modular stem |

negative |

none |

13 |

|

20 |

26,5 |

9,200 |

319 |

anti-protrusio cage + proximal femur replacement |

negative |

intraop. prox. femur fracture; early infection with MRSE, one-stage treatment |

12 |

Table 4: Data about the second stage.

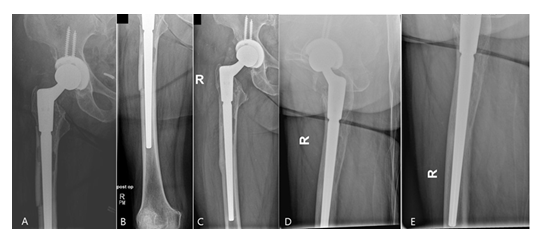

Intraoperatively, the beads could be completely removed through an endofemoral approach without having any difficulties. Based on the bone quality, presence of any osseous defects and occurrence of fractures, a cementless modular straight stem (Restoration® , Fa. Stryker, Duisburg, Germany) was used in 14 cases and a cemented proximal femur replacement stem (GMRS®, Fa. Stryker, Duisburg, Germany) in four cases, respectively. In the latter cases, the bone defects and the non-intact femoral isthmus would not have provided for a sufficient cementless fixation, therefore cemented implants were solely chosen. In all cases, Palacos R+G® (Fa. Heraeus Medical, Bad Homburg, Germany) was used. The abductor muscles were fixated onto the prosthesis through the fixation holes with non-absorbable sutures (Ethibond Excel 2-0, Fa. Ethicon). For the acetabulum, a press-fit cup (Tritanium®, Fa. Stryker, Duisburg, Germany) and an antiprotrusio cage combined with a cemented cup (Burch-Schneider cage, Fa. ZimmerBiomet, Freiburg i. Br., Germany) were implanted in eight cases, respectively, whereas a bipolar head (UHR®, Fa. Stryker, Duisburg, Germany) and a cemented constrained liner (Trident®, Fa. Stryker, Duisburg, Germany) were used in one case, respectively. Suction drains were routinely placed in all cases. The mean surgery time of the second stage was 162 [84-319] minutes. Depending on the osteotomy length, the total length of the Restoration® stems used varied between 225 and 295mm (9x 155mm, 5x 195mm with various length of cone bodies) (Figure 9). Postoperatively, all patients were allowed to put full weight-bearing onto the operated leg.

The microbiological findings of the intraoperatively taken tissue samples revealed positive findings in two cases. In both cases, the identified organisms were different to the ones primarily identified. The histological examination did not confirm the presence of an infectious membrane in all cases. Both cases were conservatively treated with antibiotic therapy for six weeks. In one of these cases, the infection persisted, and the patient was treated by means of a permanent resection arthroplasty.

Postoperative complications included pulmonal/ cardiopulmonary problems in four cases. One of these patients passed away due to a pneumonia five months after the second stage. One patient suffered from a peroneal lesion. In another case, a fracture of the greater trochanter occurred intraoperatively. The same patient suffered from a prosthesis dislocation after 34 months, which was treated conservatively by closed reduction.

At a mean follow-up of 43 [24-85] months 16/17 (94%) of the cases that underwent prosthesis reimplantation were free of any local or systemic infection signs. There was no case of a stem subsidence. All osteotomies showed a complete osseous consolidation after three to six months (Figure 9).

4. Discussion

The surgical treatment of hip PJIs can be challenging. The orthopedic surgeon is confronted with the dilemma to choose the most appropriate surgical approach that provides the best exposure and eases the surgical debridement even in difficult to achieve areas, but on the other side does not increase the morbidity and complications’ rate. Various trochanteric-, extended trochanteric osteotomies and transfemoral approaches have been described over the years at the site of aseptic THA revision surgeries with excellent results [1,3-6,18-22]. However, differences in the surgical technique, osteotomy fixation principles and technical factors frequently make a direct comparison of the studies difficult.

Literature data about transfemoral approaches at the site of hip PJI are scarce and demonstrate varying results [2, 23-29]. The osseous union rate varies from 87% [27] to 100% [25-26], whereas the infection eradication rate varies from 77% [25] to 97% [27]. The subsidence rate of the femoral stems is up to 15% [25]. Mechanical complications including femoral fractures and prosthesis dislocations are also present in strongly varying rates (fracture rate between 1.3% [2] and 23% [25]; dislocation rate between 4% [27] and 30% [25]).

Based on these facts and the known surgical techniques, we developed a novel modified approach that provides several advantages compared with the present techniques. Similar to the ETO and in contrast to the Wagner approach, the M. vastus lateralis remains macroscopically intact in its whole structure with the present technique. The sole osteotomy of the femoral shaft and not of the greater trochanter offers greater advantages regarding the postoperative mobilization after both stages. With an intact greater trochanter, the patients do not have any limitation between stages regarding the range motion since there exists no danger of dislocation of the greater trochanter. After the second procedure, the patient is allowed to put full weight-bearing on the operated leg and has a low risk of a Trendelenburg limping. Any mechanical complications such as a fracture of the greater trochanter or a possible secondary dislocation independent on the fixation method used are thereby avoided. Similar to the ETO, the osteotomy width should not exceed 1/3 of the femur circumference. This width allows not only for an excellent visualization of the cementless stem or the cement mantle, but also for a thorough debridement of the femoral canal.

The performance of the osteotomy under complete visualization is a premise for a good re-adaptation of the bone flap and guarantee of the later osseous integration. Since approximately only 1/3 of the femur circumference is exposed, no worries about the medial retraction of the vastus lateralis with regard to vascularization and innervation are present. If done correctly, the muscle can be re-attached tension-free and with no structural damage. Concerns might be raised that the detachment of the surrounding soft-tissues from the bone flap might lead to a damaged and decreased vascularization, which might negatively affect the bone union or even promote the emergence of a sequester. Our results do not support this concern since all osteotomies healed completely. Literature data have demonstrated that free, non-vascularised bone grafts can heal at the site of oncologic [30,31], infectious [32,33] or post-infectious cases [34] based on different mechanisms and pathways of cell migration, -adhesion, and -proliferation, angiogenesis, and osteogenesis [35-38]. Last but not least, the use of a small and thin blade allows for an osteotomy with no destruction of the femur, easy opening with a chissel and no danger of an iatrogenic fracture distal to the end of the osteotomy, which otherwise has to be secured with a cerclage prior to the osteotomy, as described by other authors [2].

The use of non-absorbable sutures is sufficient for secure of the bone flap in the osteotomy bed until the osseointegration has been completed, since the single placement by hand demonstrates a perfect sit with no bone step, if the osteotomy has been done technically correct. The use of non-absorbable sutures has shown promising results at the site of aseptic revisions THA. Kuruvalli et al were the first to demonstrate that the use of sutures instead of cerclages is sufficient enough to secure an extended trochanteric osteotomy with no negative impact on the bone healing [21]. Moreover, this is also of advantage from an infectiological point of view. Janz et al. showed that femoral cerclages, implanted during the explantation procedure, pose a risk factor for bacterial colonization and persistence during septic two-stage THA revision [29].

Literature data are not consistent whether the osteotomized femur has to be reopened at the second procedure. Lim et al. did not reopen the bone flap in 23 cases and performed the stem reimplantation through an endofemoral approach, as in the present study [26]. Levine et al. [24] reopened the ETO in 12 of 23 cases but in 11 cases not [24]. Fink and Oremek reopened it routinely in 76 cases and could not notice any additional drawbacks with regard to the bone union [2]. Our technique does not neccessitate the re-opening of the femoral osteotomy at the second stage, which might be associated with prolonged surgery time, higher blood loss, possibility of femoral fracture and damage of the muscles/soft-tissues. Although the possibility of an additional debridement of this region is diminished, we believe that the aforementioned advantages outweigh this single disadvantage, especially when a meticulous debridement has been carried out at the first stage. The infection eradication rate of the present study with 94% confirms this thesis.

At the site of a 2-stage septic procedure, the local antibiotic therapy is of great importance for the eradication of the PJI. It is known that the antibiotic elution from bone cement is a surface-dependent phenomenon [39], which means that the treatment with beads is superior to those when spacers are implanted from a pharmacokinetic point of view [39]. During the second stage, no difficulties were observed at the removal of the beads, which might have led to a re-opening of the osteotomized femur. A further advantage compared with the spacer treatment regards the theoretical lower risk of mechanical complications such as spacer dislocations or –fractures, especially when the patients are not compliant or able not to put weight-bearing onto the operated leg.

Compared with the mechanical complications rates from other studies, we could observe such complications in a very low rate in our collective. Following the first stage, femoral fractures were seen in two patients. After the second stage, fracture of the greater trochanter occurred intraoperatively in one case. The same patient suffered from a prosthesis dislocation after 34 months, which was treated conservatively by closed reduction. These rates are below those reported in literature [23-29].

The present technique has theoretically also some disadvantages (as every surgical technique). If not done correctly, the use of sutures might not provide for a stable fixation of the osteotomized femur, hence leading to a possible dislocation or pseudarthrosis or even fracture if the patient is not compliant. Moreover, the preparation with osteotomes in the area of the greater trochanter might lead to intraoperative fractures. Although we did not observe any of these theoretical disadvantages in our collective, we cannot exclude that these might occur especially within the early learning curve. Anecdotally, this technique has been meanwhile used in more than 50 septic cases, and the mechanical complication rate has been remained extremely low.

The present study has some limitations. The study is retrospective, and this might be associated with all known drawbacks of this study design. Our work reports on a relatively small number of patients, who have been treated with the present technique. No functional joint score was determined however, this was not the primary aim of the study. On the other side, all patients have been treated with the same protocol. The length of the follow-up is certainly a strength of the study, especially the minimum of two years from an infectiological point of view.

5. Conclusions

The management of hip PJIs is a complex procedure which is frequently associated with increased morbidity and mortality rates. The choice of the most appropriate surgical approach is a premise for the further good functional outcome but also for the successful management of the infection itself. The present technique has demonstrated very promising results at a high infection eradication- and low mechanical complications rate. Great advantages of the present approach involve leaving the greater trochanter intact and the absence of metallic cerclages, which might be of benefit at the site of an active/persistent infection.

Funding

The study did not have any financial support.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that there exists no conflict of interest.

References

- Wagner M, Wagner H. Der transfemorale Zugang zur Revision von Hüftendoprothesen. Operative Orthopädie Traumatologie 11 (1999): 278-295.

- Fink B, Oremek D. The transfemoral approach for removal of well-fixed femoral stems in 2-stage septic hip revision. Journal of Arthroplasty 31 (2016): 1065-1071.

- Fink B. The transfemoral approach for controlled removal of well-fixed femoral stems in hip revision surgery. Journal of Clinical Orthopaedics and Trauma 11 (2020): 33-37.

- Younger TI, Bradford MS, Magnus RE, et al. Extended proximal femoral osteotomy: a new technique for femoral revision arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 10 (1995): 329-338.

- Chen WM, McAuley JP, Engh CA Jr, et al. Extended slide trochanteric osteotomy for revision total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American Volume 82 (2000): 1215-1219.

- Miner TM, Momberger NG, Chong D, et al. The extended trochanteric osteotomy in revision hip arthroplasty: a critical review of 166 cases at mean 3-year, 9-month follow-up. Journal of Arthroplasty 16 (2001): 188-194.

- Anagnostakos K, Sahan I. Are cement spacers and beads loaded with the correct antibiotic(s) at the site of periprosthetic hip and knee joint infections. Antibiotics (Basel) 10 (2021): 143.

- Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, et al. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 469 (2011): 2992-2994.

- Schäfer P, Fink B, Sandow D, et al. Prolonged bacterial culture to identify late periprosthetic joint infection: a promising strategy. Clinical Infectious Diseases 47 (2008): 403-409.

- Krenn V, Morawietz L, Perino G, et al. Revised histopathological consensus classification of joint implant related pathology. Pathology Research and Practice 210 (2014): 779-786.

- Preininger B, Janz V, von Roth P, et al. Inadequacy of joint aspiration for detection of persistent periprosthetic infection during two-stage septic revision knee surgery. Orthopedics 40 (2017): 231-234.

- Boelch SP, Roth M, Arnholdt J, et al. Synovial fluid aspiration should not routinely be performed during the two-stage exchange of the knee. Biomed Research International 2018 (2018): 6720712.

- Callaghan JJ, Salvati EA, Pellici PM, et al. Results of revision for mechanical failure after cemented total hip replacement, 1979 to 1982: a two to five-year follow-up. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American Volume 67 (1985): 1074-1085.

- Böhm P, Bischel O. Femoral revision with the Wagner SL revision stem: evaluation of one hundred and twenty-nine revisions followed for a mean of 4.8 years. Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery American Volume 83 (2001): 1023-1031.

- McInnis DP, Horne G, Dvane PA. Femoral revision with a fluted, tapered, modular stem: seventy patients followed for a mean of 3.9 years. Journal of Arthroplasty 21 (2006): 372-380.

- Van Houwelingen AP, Duncan CP, Masri BA, et al. High survival of modular tapered stems for proximal femoral bone defects at 5 to 10 years follow up. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 471 (2013): 454-462.

- Pattyn C, Mulliez A, Verdonk R, et al. Revision hip arthroplasty using a cementless modular tapered stem. International Orthopaedics 36 (2012): 35-41.

- Sundaram K, Siddiqi A, Kamath AF, et al. Trochanteric osteotomy in revision total hip arthroplasty. EFORT Open Reviews 5 (2020): 477-485.

- Park CH, Yeom J, Park JW, et al. Anterior cortical window technique instead of extended trochanteric osteotomy in revision total hip arthroplasty: a minimum of 10-year follow-up. Clinics in Orthopedic Surgery 11 (2019): 396-402.

- Megas P, Georgiou CS, Panagopoulos A, et al. Removal of well-fixed components in femoral revision arthroplasty with controlled segmentation of the proximal femur. Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research 9 (2014): 137.

- Kuruvalli RR, Landsmeer R, Debnath UK, et al. A new technique to reattach an extended trochanteric osteotomy in revision THA using suture cord. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 466 (2008): 1444-1448.

- Fink B. Technical note for transfemoral implantation of tapered revision stems: the advantage to stay short. Arthroplasty Today 9 (2021): 16-20.

- Hardt S, Leopold VJ, Khakzad T, et al. Extended trochanteric osteotomy with intermediate resection arthroplasty is safe for use in two-stage revision total hip arthroplasty for infection. Journal of Clinical Medicine 11 (2021): 36.

- Levine BR, Dealla Valle CJ, Hamming M, et al. Use of the extended trochanteric osteotomy in treating prosthetic hip infection. Journal of Arthroplasty 24 (2009): 49-55.

- Morshed S, Huffman GR, Ries MD. Extended trochanteric osteotomy for 2-stage revision of infected total hip arthroplasty. Journal of Arthroplasty 20 (2005): 294-301.

- Lim SJ, Moon YW, Park YS. Is extended trochanteric osteotomy safe for use in 2-stage revision of periprosthetic hip infection? Journal of Arthroplasty 26 (2011): 1067-1071.

- Petrie MJ, Harrison TP, Buckley SC, et al. Stay short or go long? Can a standard cemented femoral prosthesis be used at second-stage total hip arthroplasty revision for infection following an extended trochanteric osteotomy? Journal of Arthroplasty 32 (2017): 2226-2230.

- Shi X, Zhou Z, Shen B, et al. The use of extended trochanteric osteotomy in 2-stage reconstruction of the hip for infection. Journal of Arthroplasty 34 (2019): 1470-1475.

- Janz V, Wassilew GI, Perka CF, et al. Cerclages after femoral osteotomy are at risk for bacterial colonization during two-stage septic total hip arthroplasty revision. Journal of Bone and Joint Infection 3 (2018): 138-142.

- Ismail A, Ashour A, Alieldin E, et al. Outcomes of non-vascularized fibular grafts in proximal humerus aneurysmal bone cysts. Cureus 16 (2024): e66428.

- Patel R, McConaghie G, Khan MM, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the outcomes of reconstruction with vascularised vs non-vascularised bone graft after surgical resection of primary malignant and non-malignant bone tumors. Acta Chirurgiae Orthopaedicae et Traumatologiae Cechoslovaca 91 (2024): 143-150.

- Tarng YW, Lin KC. Management of bone defects due to infected non-union or chronic osteomyelitis with autologous non-vascularized free fibular grafts. Injury 51 (2020): 294-300.

- Bas A, Balci HI, Kocaoglu M, et al. Augmentation with a non-vascularized autologous fibular graft for the management of Cierny-Mader type IV chronic femoral osteomyelitis: a salvage procedure. International Orthopedics 48 (2024): 439-447.

- Agrawal AC, Singh J, Garg AK, et al. Femoral diaphyseal reconstruction using free non-vascularised fibular graft in a paediatric case of postinfective gap non-union. BMJ Case Reports 17 (2024): e262287.

- Bernhard JC, Marolt Presen D, Li M, et al. Effects of endochondral and intramembranous ossification pathways on bone tissue formation and vascularization in human tissue-engineered grafts. Cells 29 (2022): 3070.

- Tang Y, Luo K, Tan J, et al. Lamini alpha 4 promotes bone regeneration by facilitating cell adhesion and vascularization. Acta Biomaterialia 126 (2021): 183-198.

- Lee EJ, Jain M, Alimperti S. Bone microvasculature: stimulus for tissue function and regeneration. Tissue Engineering Part B Reviews 27 (2021): 313-329.

- Allsopp BJ, Hunter-Smith DJ, Rozen WM. Vascularized versus nonvascularized bone grafts: what is the evidence? Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research 474 (2016): 1319-1327.

- Anagnostakos K, Wilmes P, Schmitt E, et al. Elution of gentamicin and vancomycin from polymethylmethacrylate beads and hip spacers in vivo. Acta Orthopaedica 80 (2009): 193-197.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 73.64%

Acceptance Rate: 73.64%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks