Acute Febrile Illness Surveillance and Dengue–Chikungunya Seroprevalence in Selected Community Clusters of Visakhapatnam: A Prospective Cohort Study

Dr. PJ Srinivas, Dr. KK Lakshmi Prasad*, Dr. Aruna Bula, Dr. Krishna Veni Avvaru, Dr. Paladugu Radha Kumari, Dr. Surada Chandrika

Department of Community Medicine, Andhra Medical College, Visakhapatnam, 530002

*Corresponding Author: Dr. KK Lakshmi Prasad, Andhra Medical College, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India.

Received: 29 November 2025; Accepted: 05 December 2025; Published: 18 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Srinivas PJ, Lakshmi Prasad KK, Aruna B, Krishna Veni A, Radha Kumari P, Chandrika S. Acute Febrile Illness Surveillance and Dengue–Chikungunya Seroprevalence in Selected Community Clusters of Visakhapatnam: A Prospective Cohort Study. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research. 9 (2025): 513-520.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Introduction: Vector-borne Acute febrile illness (AFI) is common in India. Dengue and Chikungunya are endemic in certain regions. The present study was planned to describe the sero-epidemiology of dengue and chikungunya in selected community clusters near Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh.

Subjects and Methods: Community-based AFI episodes of dengue and chikungunya were studied using a cohort design across five endemic clusters in Visakhapatnam. House surveys were undertaken to identify AFI cases with follow-up for 1 year. All febrile episodes were investigated using rapid diagnostic tests and laboratory-based assays. At baseline and at 12 months, a serosurvey was undertaken to estimate levels of IgG, IgM, and neutralizing antibodies associated with infections. Socio-economic status data were also collected in this survey.

Results: A total of 766 participants from the five community clusters were enrolled, of which 262 reported fevers during the one-year surveillance. 52 (19.8%) episodes of AFI were identified among 262 fever reports. Five cases each (1.9% of AFI episodes) were laboratory-confirmed as dengue and chikungunya. At baseline, 91% and 60% subjects were Dengue and Chikungunya IgG-positive, respectively. At 12 months, 92% of subjects were Dengue IgG-positive and 58% were Chikungunya IgG-positive.

Conclusion: Although the number of active cases for both Dengue and Chikungunya was very small, high seroprevalence suggests long-standing endemic transmission and substantial background immunity in the study clusters.

Keywords

<p>Dengue; Chikungunya; Andhra Pradesh; India; Seroprevalence</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Vector-borne diseases are prevalent in the Indian subcontinent and pose a considerable burden of disease [1]. Acute febrile illness (AFI) of diverse etiological and pathological origins is a common occurrence in India, characterized by fever (greater than 38°C or 100.4°F) for more than 2 days and lasting up to 14 days without organ-specific symptoms at onset [2]. In recent years, dengue, chikungunya, malaria, typhoid fever, scrub typhus, and leptospirosis, along with coinfections between these diseases, have reemerged, resulting in a significant increase in patient morbidity and mortality [3]. Among the vector-borne diseases, Dengue and Chikungunya are expanding rapidly across the country [1]. In 2024, India reported 233,519 Dengue cases, with 297 deaths (National Center for Vector-Borne Diseases Control (NCVBDC) updated July 11, 2025). As of March 31, 2025, 30876 cases of chikungunya have been reported across India, with 1741 deaths [4]. Nearly half to three-quarters of dengue cases are asymptomatic, leading to underreporting [5]. This results in underreporting of the cases. To estimate the actual burden of the disease, periodic serosurveys have been conducted in India. Multiple researchers and organizations have undertaken various efforts to assess the prevalence of Dengue and chikungunya [6,7]. However, to date, the asymptomatic-to-symptomatic disease burden ratio and the yearly seroconversion rate have not been estimated or reported. Some studies have attempted to explain the burden of dengue or chikungunya but have failed to reflect the National disease burden accurately [6]. Thus, a systematically planned study, to estimate the incidence of acute febrile illness and to describe the sero-epidemiology of dengue and chikungunya in selected community clusters near Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, was planned. This manuscript presents the findings of the field study conducted by the authors and the team.

2. Material and Methods

This Prospective, Community-based, Multicenter field study aimed to estimate the incidence of Dengue and Chikungunya using a cohort study design. The site selection was based on the major endemic areas with Dengue and Chikungunya cases.

2.1 Study objectives:

The objectives of the study were to estimate

- Proportion of acute febrile illness episodes detected during 12 months of follow-up.

- Proportion of symptomatic laboratory-confirmed Dengue and chikungunya infection episodes during 12 months of follow-up.

- To assess the baseline and 12-month seroprevalence of dengue and chikungunya infections in the study cohort.

- To describe the socio-demographic and household characteristics of the study population.

2.2 Methodology

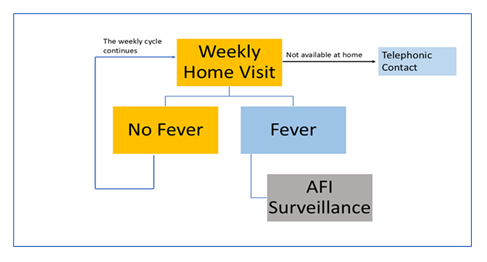

The study protocol was finalized in accordance with the consensus and suggestions received from the Technical Advisory Group of the National Biopharma Mission, BIRAC to study the Dengue and Chikungunya serosurveys at 12-month intervals, at baseline (0 months) and at the end of the study period (12 months). Andhra Medical College in Visakhapatnam was identified as one of the sites. The study duration was 16 months. The study included a 2-month preparatory phase, followed by 12 months of data collection (including a serosurvey at 0 and 12 months) and a 2-month post-study period. The Field study team and project team were constituted to manage the project's operational aspects. The acute febrile illness surveillance was established through weekly follow-up (self-reported, telephonic calls, and home visits). All febrile episodes were investigated using rapid diagnostic tests and laboratory-based assays. Each study participant was followed for a period of one year. The baseline serosurvey consisted of estimates of IgG, IgM, and Neutralizing antibodies to dengue and chikungunya in febrile cases screened during the house surveys. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were predefined in the protocol. Participants were selected based on the eligibility criteria. Participants presenting with ongoing fever episodes or a history of AFI within 3 calendar days before enrolment in the cohort were excluded. The study plan is summarized in Figure 1.

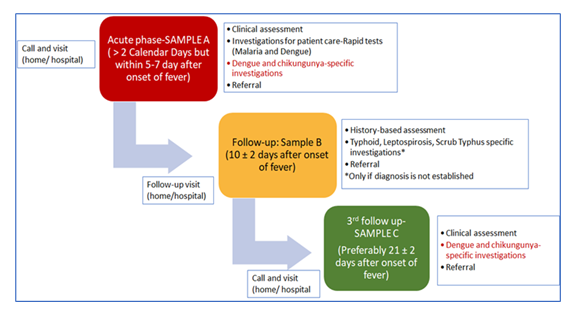

In the selected clusters, consecutive Households were approached; consenting participants who complied with the inclusion/exclusion criteria were included. The age-proportionate sampling technique, based on age-proportionate bands and the age-group proportions in the community, was used. The study protocol included an active and passive surveillance system for febrile cases (Figure 2: Active Surveillance Plan).

Passive reporting included individual, community, and health facility-level reporting from both private and public hospitals on any patients with fever. A monthly contact with the community leader and the hospital was explored to strengthen the surveillance system. Once a febrile participant was identified, the diagnostic team would promptly visit the site.

The diagnostic team was responsible for confirming the acute febrile illness, symptoms, and onset date. If the visit coincided with the acute fever phase ( within 3 – 7 days of the onset of fever), the participant was considered for acute-phase workup (Table 1). This included sample collection for laboratory tests, such as Dengue (Using NS1, IgG, and IgM ELISA Tests) and Chikungunya (using IgM tests—only for seronegative individuals).

Table 1: Case definition.

|

Case Definition Acute Febrile Illness: Report of fever for >2 days with documented temperature recording of ≥38oC or ≥100.4oF on both days to be included as a febrile illness •A self-reported perception of fever for >2 days which required intake of Paracetamol or any other antipyretic irrespective of documented temperature recording •Children less than 6 years: Caregivers report to be accepted irrespective of documented temperature recording. |

In the follow-up phase (Day 10 ± 2 of fever onset), participants were examined for ongoing fever episodes. In the Convalescent Phase (21±2 days after the onset of fever), all participants with AFI were tested for dengue and chikungunya convalescent serology to determine the co-infection rates of dengue and chikungunya. During this visit, paired testing of samples for Seroconversion and a four-fold rise in titers was evaluated. Data collection was done using a paperless data management platform (SOMAARTH-3). The data was synchronized into the INCLEN server by the data manager after preliminary cleaning, preferably within 48 hours of collecting the subject information.

2.3 Sample Size Determination:

The sample size for the proposed study was calculated based on an assumed incidence rate of 5.0 dengue symptomatic cases per 100 person-years of follow-up [8,9,10] with a 15% margin of error (Relative precision), yielding a sample size of 3415. To account for a potential 10% loss to follow-up and a Design effect of 2, the target number of individuals to be followed for a year is estimated to be 7512 across 10 sites, or 752 per site [11]. A sample of at least 765 individuals was required to draw conclusions from the study.

2.4 Statistical Plan

The statistical analysis was performed using STATA software. Descriptive analysis was conducted to examine population characteristics, presented as proportions (%) and means (SD) for general subject demographics, socioeconomic data, the incidence of Dengue, chikungunya, and other vector-borne diseases; the number of fever episodes, the mean duration of fever, and the number of participants with rapid diagnostic and laboratory-confirmed cases were analyzed. No incidence rate estimates based on person-time were reported due to the limited number of confirmed dengue and chikungunya outcomes.

3. Results

Our institute was selected as a participating center in this project. The Institutional Ethics Committee approved the study protocol before the project's commencement. The target subject enrollment comprised 766 participants from 5 clusters near Simhachalam, Visakhapatnam. The five clusters, located near Simhachalam, Visakhapatnam, provide community-based data from partly urban and peri-urban settings. The five clusters identified were Adavivaram-1 (136 subjects), Adavivaram-2 (151 subjects), Indhira Nagar (156 subjects), Laxmi Nagar (190 subjects), and Pedagadili-1 (133 subjects). 407 (53.13%) subjects consented to provide socio-economic status data (Table 2).

Table 2: Socio-demographic profile of study participants (n = 766)

|

Parameters |

N (%) |

|

Educational Status |

|

|

Upto 10th |

502(49.6%) |

|

School year 11 |

12 (1.57%) |

|

School year 12 |

81 (10.57%) |

|

Diploma/Certificate |

11 (1.44%) |

|

Graduate |

61 (7.96%) |

|

Post Graduate |

15 (1.96%) |

|

Can sign/Can read |

47 (6.14%) |

|

Illiterate |

112 (14.62%) |

|

Marital Status |

|

|

Married |

431 (56.27%) |

|

Unmarried |

253 (33.03%) |

|

Widowed |

73 (9.53%) |

|

Separated |

7 (0.91%) |

|

Divorced |

2 (0.26%) |

|

Occupation |

|

|

House wife/ Home maker |

290 (37.86%) |

|

Student |

207 (27.02%) |

|

Daily Labour/ Labour NREGA/ other contract work |

78 (10.18%) |

|

Private job |

66 (8.62%) |

|

Professional (Self-employed) |

32 (4.18%) |

|

Others |

93(10.50%) |

|

Does any member of this household own this house or any other house? (n=407) |

|

|

Yes |

301 (73.96%) |

|

No |

106 (26.04%) |

|

Does any member of the household own any agricultural land (n=407) |

|

|

Yes |

25 (6.14%) |

|

No |

382 (93.86%) |

|

How many rooms in this household are used for sleeping? (n=407) |

1.82 |

|

Number of members in the household (n=407) |

3.82 |

|

Primary Source of Drinking Water (n=407) |

|

|

Bottled Water |

4 (0.98%) |

|

Community RO Plant |

3 (0.74%) |

|

Piped to Dwelling |

256 (62.90%) |

|

Piped to Yard / Plot |

25 (6.14%) |

|

Public Taps / Standpipe |

116 (28.50%) |

|

Tube Well or Borehole |

3 (0.74%) |

|

Primary Fuel for Cooking (n=407) |

|

|

LPG / Natural Gas |

407 (100.00%) |

|

Solid Waste Disposal (n=407) |

|

|

Closed Drain |

56 (13.76%) |

|

Manual Collection |

350 (86.00%) |

|

Open Drain |

1 (0.25%) |

|

Type of toilet facility (n=407) |

|

|

Flush to Piped Sewer System |

1 (0.25%) |

|

Flush to Septic Tank |

401 (98.52%) |

|

No facility/uses open space or Field |

5 (1.23%) |

|

Do you share the toilet facility with any other household (n=407) |

|

|

Yes |

5 (1.23%) |

|

No |

402 (98.77%) |

|

Does any usual member of this household have a bank account or a post office account? (n=407) |

|

|

Yes |

403 (99.02%) |

|

No |

4 (0.98%) |

Out of 766 subjects, 286 were Male and 480 were Female subjects. The largest age group was 20-49 years (408 subjects), accounting for 53.26% of the sample. There were 32 (4.18%) subjects between the ages of 2-4 years and 55 (7.18%) subjects between 5-9 years of age. 114 (14.88%) subjects belonged to the 50-64 years age group, and 47 (6.14%) subjects were 65 years and above. 61 (7.96%) subjects were graduates, 122 (15.93%) had studied up to the 10th grade, and 112 (14.62%) were illiterate.

431 (56.27%) subjects were married, and 253 (33.03%) were unmarried. 73 (9.53%) subjects were widowed. The majority of the women subjects were homemakers (37.86%), followed by students (27.02%), daily wage workers (10.18%), those in private jobs (8.62%), and self-employed individuals (4.18%). 301 (73.96%) subjects resided in their own homes, and only 25 (6.14%) subjects owned agricultural land. 286 (70.27%) subjects lived in dwellings made of stone/marble/granite homes, whereas 108 (26.54%) had dwellings made of concrete. 350 (86%) subjects lived in houses with RCC/RBC/cement/concrete roofs, and burnt bricks were used in the construction of 405 (99.5%) dwellings. The average number of family members was 3.82 (±1.31), and the average number of sleeping rooms was 1.82 (±0.47). The number of average children under 5 years per household was 0.22 (±0.52). 256 (62.90%) subjects received piped water supplied by local authorities to their homes, and all homes had access to LPG/natural gas for cooking. 86% (350) of homes had a manual waste collection system, and 98.52% (401) of the subjects had toilet facilities connected to the septic tank.

The majority (99.02%) of households had bank accounts, and almost all homes had the necessary household appliances and electricity connections. Mobile phone connections were available to 99.50% of the subjects. Sixty-seven-point three two percent (67.32%, 274) of the subjects owned a two-wheeler, and 24.32% (99) used a bicycle as their primary mode of transport.

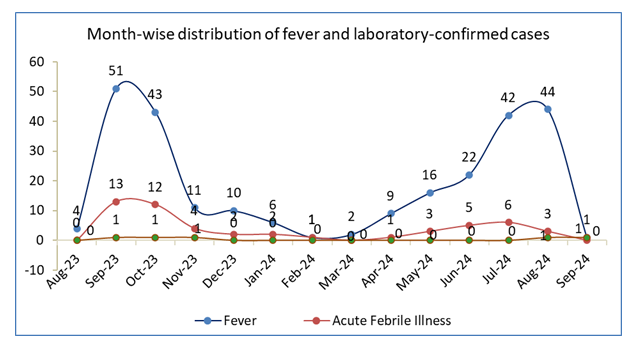

The month-wise distribution of fever and laboratory-confirmed cases is shown in Figure 3.

A total of 262 fever episodes were reported during the surveillance period; 52 (19.85%) met the criteria for Acute Febrile Illness. Most AFI episodes occurred between September 2023 and October 2023, during the post-monsoon season, accounting for almost half of the total (25 of 52). Five Dengue cases were detected and confirmed by the laboratory: one in September 2023, two in October 2023, one in November, and one in September 2024. No apparent clustering of Dengue infection occurred, except for this early seasonal peak. The temporal trends show that febrile illnesses were relatively higher during the monsoon and immediate post-monsoon months, which agrees with regional transmission trends for vector-borne infections in Visakhapatnam.

Among the 52 AFI cases, after 1 year of follow-up, 5 were confirmed as Dengue IgM-positive and 5 as Chikungunya IgM-positive, indicating a low proportion of virologically confirmed infections among the total febrile illness burden (Table 3).

Table 3: Detection of Dengue by Serological and NS1antigen tests in Acute, Follow-up and Convalescent phases (AFI=52).

|

Phase |

Parameters |

n (%) |

|

By Diagnosis Method |

||

|

Acute |

1. Dengue IgM Result |

3 (5.88%) |

|

2. NS 1 Result |

- |

|

|

3. Dengue IgG Result |

45 (88.24%) |

|

|

4. Dengue NS 1 |

- |

|

|

Follow-up |

5. Dengue IgM |

2 (3.92%) |

|

6. Dengue IgG |

4 (7.84%) |

|

|

Convalescent |

Dengue IgG Result |

43 (84.31%) |

|

Dengue IgM Result |

2 (3.92%) |

At baseline, 91% of participants were Dengue IgG-positive, while 60% were Chikungunya IgG-positive. At 12 months, Dengue IgG positivity and Chikungunya IgG positivity remained virtually unchanged at 92% and 58%, indicating stable serological profiles in the community over time. These small differences are compatible with assay variability and minor differences in the subset available for follow-up, rather than substantial changes in seroprevalence over time.

At the 12-month follow-up, 16 were lost to follow-up, including four deaths unrelated to Dengue or Chikungunya.

4. Discussions

Dengue and chikungunya are dominant vector-borne viral diseases in India, showing marked regional variation and periodic outbreaks. Due to regional variability, it is challenging to estimate national incidence and prevalence accurately. The aspects of missed diagnosis and underreporting also contribute to the inaccuracy of the incidence and prevalence estimates in the country. This has been one of the aspects for which our population survey was planned.

We selected clusters in the state that were partly urbanised and partly rural as representative samples. The population in these clusters was similar in terms of socio-economic parameters and can be considered homogeneous. A house-to-house active surveillance approach was implemented to identify febrile illnesses For every suspected case, blood samples were collected for confirmation. The sample population of 766 was representative, from which 262 fever cases were identified, including 52 (19.8%) cases of acute febrile illness. Among these 52 cases, five each were confirmed cases of dengue and chikungunya. Among the dengue cases, three subjects were in the acute phase and two in the convalescent phase.

At baseline, among the collected samples, 91% of subjects were positive for Dengue IgG antibodies, and 60% were positive for Chikungunya IgG antibodies. At the end of 12 months, 750 of the 766 enrolled subjects were resampled; 92% were positive for Dengue IgG antibodies, and 58% were positive for Chikungunya IgG antibodies.

The confirmed active infections of dengue and chikungunya in our study accounted for 0.65% of the entire cohort. This incidence rate is significantly lower than the reported incidence rate of Dengue and Chikungunya in the country. The reported overall estimate of the prevalence of laboratory-confirmed dengue infection among clinically suspected patients was 38.3% (95% CI: 34.8%-41.8%), and the reported pooled estimate of dengue seroprevalence in the general population of confirmed patients was 56.9% (95% CI: 37.5-74.4%). Significant heterogeneity in reported outcomes (p < 0.001) is reported [12].

Regarding chikungunya, the reported average detection rate in a prospective study was 25.37% of patients, as detected by RT-PCR and/or IgM-ELISA [13]. In the same survey, the highest number of cases was detected in the south (49.36%), followed by the west (16.28%) and the north (0.56%) of India [13]. Although chikungunya was first reported in India in 1963, it resurfaced in 2005 and has since become endemic, with disease outbreaks occurring in several parts of the country. Several mutations have been identified in circulating strains of the virus, resulting in better adaptations or increased fitness in the vector(s), effective transmission, and disease severity [14,15].

Similarly, Dengue fever was first reported in India in 1946. No significant dengue activity was reported anywhere in the country until 1963-1964, when an epidemic occurred on the eastern coast of India, spreading to Delhi and Kanpur, and then gradually to the southern part [16]. The reported national Dengue hotspots covered 66.72% of the region, whereas cold spots covered 16.69% [17].

There has been a drastic change in climate patterns in recent years, the impact of which is evident in the rapidly changing trends of many diseases, particularly vector-borne diseases with emerging serotypes [18,12].

In our study, the number of active cases of both Dengue and Chikungunya was low; however, seroprevalence was high among the study population. This finding corroborates the reported data on chikungunya and dengue in the country. The reported overall prevalence of IgG antibodies against chikungunya is 18.1% (95% CI, 14.2-22.6), with an overall seroprevalence of 21.6% (15.9-28.5) among individuals aged 18-45 years [19]. In our study, the highest seroprevalence of 63.20% was observed in the 20- 49-year age group.

As far as Dengue is concerned, the reported overall seroprevalence of dengue infection in India is 48·7% (95% CI 43·5-54·0); increasing from 28·3% (21·5-36·2) among children aged 5-8 years to 41·0% (32·4-50·1) among children aged 9-17 years and to 56·2% (49·0-63·1) among individuals aged 18-45 years [20]. In our study, the reported seroprevalence is 58.05% in the population aged 20-49 years.

Given that dengue is endemic in most states, reported seroprevalence has been 60.3% among individuals aged 5-45 years [21,22]. The re-emergence of chikungunya has been linked to a combination of genetic variation, population immunity, and vector propagation [7].

In general, both these diseases are endemic, with regional outbreaks triggering humoral immunity in the population. Serological surveys provide the most direct measure of the immunity landscape for infectious diseases, and our study results support this. Although the active infection patient population was small, the presence of IgG antibodies across the age groups reflects the endemicity of these two infections.

5. Limitations and Strengths:

This study has certain limitations. First, the sample size was relatively small, comprising only five clusters in Visakhapatnam, limiting the generalizability of the findings to the broader population of Andhra Pradesh. The small number of clusters and the limited number of outcome events restricted our ability to use more complex multilevel models. As a result, some age-specific incidence estimates have wide confidence intervals and should be interpreted with caution. Second, fever surveillance relied partly on self-reporting and weekly follow-up, which may have introduced recall bias and underreported mild or short-duration febrile episodes. Thirdly, no entomological or vector surveillance data were collected alongside serological findings, which could have provided insights into mosquito density, breeding patterns, and vector control measures. Finally, while IgG seropositivity indicates past exposure, it does not allow precise estimation of the time of infection, and cross-reactivity with other flaviviruses cannot be completely ruled out. Despite these limitations, our study demonstrates the heterogeneity of Dengue and Chikungunya in these clusters of Andhra Pradesh with long-term follow-up and data on long-term seroprevalence.

6. Conclusions

Our community-based cohort study in five clusters near Visakhapatnam demonstrates a high seroprevalence of Dengue and Chikungunya, with relatively few symptomatic, laboratory-confirmed infections detected over one year of active surveillance. These findings are consistent with long standing endemic transmission and substantial population-level immunity. Seasonal variations, geographic factors, and environmental factors are significant contributors to mosquito breeding. A necessary strategy to reduce vector populations is crucial for preventing disease prevalence and incidence.

Acknowledgment:

We acknowledge the Department of Biotechnology’s National Biopharma Mission (NBM)—an Industry–Academia collaborative initiative implemented by BIRAC for accelerating biopharmaceutical innovation. Authors would also like to acknowledge Alzasyno Life Sciences Private Limited for their assistance in preparation of this manuscript; Ms. Jiju and Mr. Suresh helped with statistical analysis, and manuscript writing by Dr. Manjusha Rajarshi.

Funding Source:

The project is funded by the Biotechnology Industry Research Assistance Council (BIRAC).

Conflict of Interest Statement:

None to declare.

Ethics Committee Approval:

This project is approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of King George Hospital, Visakhapatnam, on 25th June 2024. Protocol ID: DHS DRIVEN/2020/AFI Surveillance. Written informed consent was obtained from all adult participants and from parents/guardians of minors before enrolment.

Data availability:

The authors are willing to provide the study data for verification if requested by the publishers.

References

- Kumar G, Baharia R, Singh K, et al. Addressing challenges in vector control: a review of current strategies and the imperative for novel tools in India's combat against vector-borne diseases. BMJ Public Health 2 (2024): e000342.

- Rhee C, Kharod GA, Schaad N, et al. Global knowledge gaps in acute febrile illness etiologic investigations: a scoping review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 13 (2019): e0007792.

- Bala A, Singh K, Chhabra A, et al. Incidence of dengue, chikungunya, malaria, typhoid fever, scrub typhus, and leptospirosis in patients presenting with acute febrile illness at a tertiary care hospital, Amritsar. J Vector Borne Dis (2025): [Online ahead of print].

- Facts about Chikungunya. Directorate of National Vector-Borne Disease Control Program, et al. Facts about chikungunya. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

- De Santis O, Bouscaren N, Flahault A, et al. Asymptomatic dengue infection rate: a systematic literature review. Heliyon 9 (2023): e20069.

- Dinesh A, Bommu SPR, Balakrishnan A, et al. Mapping the outbreaks of dengue and chikungunya and their syndemic in India: analysis utilizing IDSP data. Cureus 17 (2025): e77193.

- Babu NN, Jayaram A, Shetty U, et al. Clinical and molecular epidemiology of chikungunya outbreaks during 2019–2022 in India. Sci Rep 15 (2025): 27280.

- Shah PS, Alagarasu K, Karad S, et al. Seroprevalence and incidence of primary dengue infections among children in rural Maharashtra, Western India. BMC Infect Dis 19 (2019): 296.

- Rose W, Sindhu KN, Abraham AM, et al. Incidence of dengue illness among children in an urban setting in South India. Int J Infect Dis 84 (2019): S15-S18.

- Sinha B, Goyal N, Kumar M, et al. Incidence of lab-confirmed dengue fever in a pediatric cohort in Delhi, India. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 16 (2022): e0010333.

- Braga C, Albuquerque MF, Cordeiro MT, et al. Prospective birth cohort in a hyperendemic dengue area in Northeast Brazil: methods and preliminary results. Cad Saude Publica 32 (2016): S0102-311X2016000100601.

- Ganeshkumar P, Murhekar MV, Poornima V, et al. Dengue infection in India: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis 12 (2018): e0006618.

- Ray P, Ratagiri VH, Kabra SK, et al. Chikungunya infection in India: results of a prospective hospital-based multicentric study. PLoS One 7 (2012): e30025.

- Chaudhary S, Jain J, Kumar R, et al. Chikungunya virus molecular evolution in India since its re-emergence in 2005. Virus Evol 7 (2021): veab074.

- Translational Research Consortia (TRC) for Chikungunya Virus in India, et al. Current status of chikungunya in India. Front Microbiol 12 (2021): 695173.

- Gupta N, Srivastava S, Jain A, et al. Dengue in India. Indian J Med Res 136 (2012): 373-390.

- Mandal B, Mondal S, et al. Unveiling spatio-temporal mysteries: decoding India’s dengue and malaria trend (2003–2022). Spat Spatiotemporal Epidemiol 51 (2024): 100690.

- Bhattacharyya H, Agarwalla R, et al. Trend of emerging vector-borne diseases in India: way forward. Int J Community Med Public Health 9 (2022): 2730-2733.

- Kumar MS, Kamaraj P, Khan SA, et al. Seroprevalence of chikungunya virus infection in India, 2017: a population-based serosurvey. Lancet Microbe 2 (2021): e41-e47.

- Wilder-Smith A, Rupali P, et al. Estimating the dengue burden in India. Lancet Glob Health 7 (2019): e988-e989.

- Murhekar MV, Kamaraj P, Kumar MS, et al. Burden of dengue infection in India, 2017: a cross-sectional population-based serosurvey. Lancet Glob Health 7 (2019): e1065-e1073.

Mutheneni SR, Morse AP, Caminade C, et al. Dengue burden in India: recent trends and importance of climatic parameters. Emerg Microbes Infect 6 (2017): e70.

Impact Factor: * 5.8

Impact Factor: * 5.8 Acceptance Rate: 71.20%

Acceptance Rate: 71.20%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks