Beach-Chair versus Lateral Decubitus Positioning: A Comparison of Set-Up Time and Cost for Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair

Matthew T. Glazier, DO1, Hayden B. Schuette DO1, Brian D. Sullivan, DO2, Stephen P. Wiseman, DO3, Nathaniel K. Long, DO3

1Department of Orthopedic Surgery, OhioHealth/Doctors Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA

2Department of Orthopedic Surgery, OrthoAtlanta, Atlanta, Georgia

3Bone and Joint Center, OhioHealth Orthopedic Surgeons, Columbus, OH, USA

*Corresponding Author: Matthew T. Glazier, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, OhioHealth/Doctors Hospital, Columbus, OH, USA.

Received: 11 January 2024; Accepted: 23 January 2024; Published: 31 January 2024

Article Information

Citation: T. Glazier, Hayden B. Schuette, Brian D. Sullivan, Stephen P. Wiseman, Nathaniel K. Long. Beach-Chair versus Lateral Decubitus Positioning: A Comparison of Set-Up Time and Cost for Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair. Journal of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine. 6 (2024): 18-24.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Introduction: Patients can be positioned in either the beach-chair or lateral decubitus position when undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Authors have argued the advantages and disadvantages of both positions. The primary purpose of this retrospective review is to compare the time for set-up, identify differences in cost, and secondarily report on any complications experienced depending on patient positioning during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.

Materials and Methods: This single-institution retrospective review included two hundred and ninety-six patients who underwent arthroscopic shoulder surgery between January 2018 and January 2019. Two groups were established, one for patients in the beach-chair position and another for those in the lateral decubitus position. Primary outcomes collected included time from intubation to incision, time from closure to extubation, total procedure time, supply costs, implant costs, and total supply costs. Secondary outcomes collected included minor and major complications and the number of staff used during the procedure.

Results: One hundred and fifty-nine patients were in the beach-chair group, and 137 were in the lateral decubitus group. There were no statistical differences in demographics. The lateral decubitus positioning group had a significantly shorter time from intubation to incision (29.3 min vs. 37.4 min, P <0.001), lower total operative time (60.6 min vs. 85.6 min, P < 0.001), required less staff (7.0 vs. 7.5, P < 0.001), and decreased isolated supply costs ($238 vs. $415, P < 0.001). There was no significant difference in time from closure to extubation between the beach-chair and lateral positions (16.6 min vs. 16.4 min, P=0.838). Total implant cost was higher in the beach-chair group than in the lateral decubitus group ($1,502 vs. $1,152, P=0.053), although this difference did not reach statistical significance. There were no significant complications requiring further surgical intervention. All minor complications were resolved with conservative measures by final follow-up with no statistically significant difference between the two groups (1.9% vs. 5.1%, P=0.196).

Conclusions: The results of our study demonstrate that arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in the lateral decubitus position requires decreased time for set up and has decreased supply costs. Strategies should be implemented to improve efficiency, reduce overall operative time, and lower supply costs. Ultimately, the decision on arthroscopic shoulder positioning should be based on surgeon comfort and training for optimal patient outcomes.

Level of Evidence: Level III: Retrospective comparative study

Keywords

<p>Beach-chair; Lateral decubitus; Set-up time; Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair; Supply costs; Patient positioning</p>

Article Details

Level of Evidence:

Level III: Retrospective comparative study

1. Introduction

Shoulder disease is a significant source of disability in the United States and ranks only behind chronic knee pain in society’s burden of musculoskeletal disease [1]. Among shoulder disease, rotator cuff pathology is the leading cause of shoulder-related evaluation by orthopedic surgeons [2]. In the general population, rotator cuff tears have been shown to have a prevalence as high as 34%, and there is an apparent increase in prevalence with age [3-6]. While many rotator cuff tears are asymptomatic or successfully treated nonsurgically, it can be expected that 50% of tears will progress in size and symptoms, which may necessitate surgical intervention [7,8]. With the large prevalence of rotator cuff tears, it has been reported that over 250,000 rotator cuff repairs occur annually in the United States [9].

Rotator cuff repair, which is most commonly performed arthroscopically, is typically performed in either a beach-chair or lateral decubitus position [9-11]. Most surgeons choose patient positioning based on training and comfort level, but several arguments can be made for both positions. Proponents of the beach-chair position often point to its upright, anatomic vantage point and the ease of performing an exam under anesthesia and converting to open procedures [11-13]. Conversely, proponents of the lateral decubitus position note that the traction allows for an increased working space within the glenohumeral joint and subacromial space and that the set-up may be quicker and require less costly equipment [11,12]. However, to our knowledge, objective studies have yet to compare the amount of time required for set-up or the supply cost associated with the lateral decubitus and beach-chair positions.

The primary purpose of this retrospective review was to compare the set-up time and supply cost between the beach-chair and lateral decubitus positions for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Secondary outcome measures included differences in staff requirements and 90-day complication rates between the beach-chair and lateral decubitus positions for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair.

2. Methods and Materials

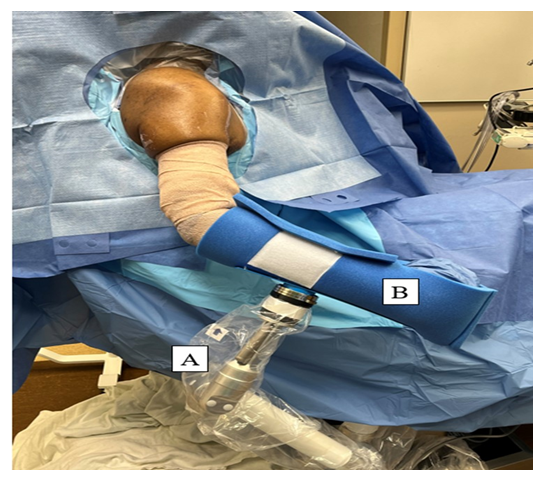

A retrospective review of patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair was performed between January 2018 and January 2019. All patients underwent surgery at a single, high-volume ambulatory surgical center (ASC) by one of two fellowship-trained shoulder and elbow surgeons (NKL, SPW). Patient positioning was dictated by surgeon preference, with one surgeon (N.K.L) using the lateral decubitus position and the other surgeon (S.P.W) almost exclusively using the beach chair position. All patients were positioned by the ASC staff, who were all experienced in the set-up of both positions. Patients were positioned using a rigid hip positioner on a flat-top operating table for the lateral decubitus position. The arm was placed into traction using a lateral decubitus shoulder traction tower (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) and a disposable STAR sleeve with self-adherent wrap (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) (Figure 1). For the beach-chair position, the patient was positioned onto a compatible operating table with disposable foam face padding (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) (Figure 2) and a Trimano pneumatic arm holder with the disposable arm wrap (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Intraoperative photograph demonstrating patient positioned in the lateral decubitus position depicting the traction tower (labeled A) and disposable STAR sleeve with self-adherent wrap (labeled B).

Figure 2: The patient properly positioned in the upright beach-chair position with head and neck within a padded foam head positioner (Labeled A).

Figure 3: Intraoperative photograph demonstrating patient in the beach-chair position utilizing a Trimano pneumatic arm holder (Labeled A) and its associated disposable arm wrap (Labeled B).

Inclusion criteria included patients 18 years or older, patients with a minimum of 3 months follow-up, and patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair by one of two senior authors (N.K.L, S.P.W). Patients were not excluded if they had concomitant procedures such as a biceps tenodesis, subacromial decompression, and distal clavicle resection. Exclusion criteria included patients who underwent manipulation under anesthesia prior to shoulder arthroscopy, which would confound the time from intubation to incision.

Demographic data, including age, sex, and body mass index (BMI), were collected. The primary outcome measures of this study included timing and cost variables. Intraoperative data were collected from the intraoperative nursing and anesthesia notes, including anesthesia staff count, total staff count, time from intubation to incision, procedure time, and time from closure to extubation. Total cost, implant cost, total supply cost, and isolated supply cost were provided to the authors by the institutional finance and quality improvement teams. Total cost included implant and total supply cost. Total supply cost included all drapes and disposable equipment. In contrast, isolated supply costs included any supplies specific to the beach-chair or lateral decubitus position. Secondary outcomes included any intraoperative or post-operative complications. Expenses related to the initial purchase of the lateral decubitus shoulder traction tower (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL), the rigid hip positioner, the disposable foam face padding (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) and the Trimano pneumatic arm holder (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) were not included.

Data was collected from the electronic medical record and stored in an Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA) document. Categorical data was expressed as numbers and percentages and was analyzed using the chi-square test. Continuous data was expressed as means and standard deviations and was analyzed using the student’s t-test. A P-value of less than 0.05 was used to determine statistical significance.

3. Results

Two-hundred and ninety-six patients were included in this retrospective review (Table 1). One hundred and fifty-nine patients were included in the beach chair group, and 137 were included in the lateral decubitus group. The average patient age was similar and was 51.6 years in the beach chair group and 52.9 years in the lateral decubitus group. There was no statistical difference (P = 0.15) in patient sex between the two groups. Lastly, BMI was similar in both groups.

|

|

Beach Chair |

Lateral Decubitus |

P-Value |

|

Patients |

159 |

137 |

- |

|

Age, mean ± SD |

51.6 ± 12.7 |

52.9 ± 12.4 |

0.38 |

|

Sex, n (%) |

0.15 |

||

|

Male |

75 (47.2) |

76 (55.5) |

|

|

Female |

84 (52.8) |

61 (44.5) |

|

|

BMI, mean ± SD |

32.2 ± 7.8 |

32.3 ± 6.7 |

0.95 |

|

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation |

|||

Table 1: Patient Demographics.

Intraoperative outcomes are shown in Table 2. Provider 1 (N.K.L) did 99.3% of the lateral decubitus procedures and only one beach chair procedure, while provider 2 (S.P.W) did 99.4% of the beach chair procedures and only one lateral decubitus procedure. The lateral decubitus group required significantly less time from intubation to incision than the beach-chair group (29.3 min vs. 37.4 min); however, no significant difference was found in time from closure to extubation. Isolated supplies costs, or those related directly to the patient positioning, were significantly less in the lateral decubitus group compared to the beach chair group ($238 vs. $415). Total supplies and total costs were also significantly lower in the lateral decubitus group. The lateral decubitus group had significantly fewer total staff and anesthesia staff than the beach-chair group. No significant difference was found in implant cost.

|

|

Beach Chair |

Lateral Decubitus |

P-Value |

|

Provider, n (%) |

<0.001 |

||

|

1 |

1 (0.6) |

136 (99.3) |

|

|

2 |

158 (99.4) |

1 (0.7) |

|

|

Laterality, n (%) |

0.845 |

||

|

Left |

69 (43.4) |

61 (44.5) |

|

|

Right |

90 (56.6) |

76 (55.5) |

|

|

Total staff count, mean ± SD |

7.5 ± 1.0 |

7.0 ± 0.8 |

<0.001 |

|

Anesthesia staff count, mean ± SD |

2.9 ± 0.9 |

2.7 ± 0.7 |

0.036 |

|

Time (min), mean ± SD |

|||

|

Intubation to incision |

37.4 ± 7.1 |

29.3 ± 8.2 |

<0.001 |

|

Closure to extubation |

16.6 ± 5.4 |

16.4 ± 11.2 |

0.842 |

|

Procedure time |

85.6 ± 25.4 |

60.6 ± 21.2 |

<0.001 |

|

Cost, mean ± SD |

|||

|

Isolated supplies cost |

$415 ± $575 |

$238 ± $123 |

<0.001 |

|

Total supplies cost |

$987 ± $195 |

$828 ± $169 |

<0.001 |

|

Implant cost |

$1502 ± $1663 |

$1152 ± $1383 |

0.052 |

|

Total cost |

$2489 ± $1704 |

$1981 ± $1505 |

0.007 |

Table 2: Intraoperative Outcomes.

There was no significant difference (P = 0.196) in total complication rates (Table 3). There were three complications (1.9%) in the beach-chair group, all of which were superficial infections. There were seven complications (5.1%) in the lateral decubitus group. Two patients developed superficial hematomas, one patient developed a lower extremity deep vein thrombosis, one patient had persistent neck swelling at the site of their pre-operative interscalene block, one patient had numbness in their tongue, which resolved after their first post-operative visit, and two patients had paresthesias in their hand from the traction tower, which resolved several days after surgery.

|

|

Beach Chair |

Lateral Decubitus |

P-Value |

|

Superficial infection, n (%) |

3 (1.9) |

- |

- |

|

Hematomas, n (%) |

- |

2 (1.5) |

- |

|

Hand paresthesias n (%) |

- |

2 (1.5) |

- |

|

Tongue numbness, n (%) |

- |

1 (0.7) |

- |

|

Neck swelling, n (%) |

- |

1 (0.7) |

- |

|

Lower extremity DVT, n (%) |

- |

1 (0.7) |

- |

|

Total, n (5) |

3 (1.9) |

7 (5.1) |

0.196 |

Table 3: Complications.

4. Discussion

This is the first study comparing set-up time and supply costs differences between the beach-chair and lateral decubitus positions for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. The main results of our study demonstrate that for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, the lateral decubitus position takes less time from intubation to incision and has lower supply costs when compared to the beach-chair position. Additionally, no significant difference in 90-day complication rates was found.

Those who advocate for lateral decubitus positioning during shoulder arthroscopy often state an advantage of the ease of set-up compared to the beach chair position [11]. Other opinion-based advantages include decreased steps involved with set-up, decreased equipment, fewer assistants required, and improved visualization [11-13]. No previous studies have objectively compared set-up time for both positions in patients undergoing arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Our results support this common argument, with the lateral decubitus group objectively requiring less time to set up (intubation time to incision time) in comparison to the beach-chair group (29.3 min vs. 37.4 min, P <0.001) as well as fewer total OR staff (7.5 vs. 7.0, P < 0.001). For set-up in the beach-chair position, a significant amount of set-up time is spent ensuring proper positioning of the patient's head and neck within the padded foam head positioner and maneuvering the powered beach-chair compatible operating room table into the appropriate position. Applying pneumatic arm holders such as the Trimano (Arthrex, Naples, FL) also requires additional set-up time in the beach-chair position. Set-up in the lateral decubitus position requires assistance positioning the patient on their side with either a bean bag or hip positioner and correctly setting up a traction device with pulley and weights. If extrapolated over time, this difference in set-up time and staffing may significantly affect overall surgical center efficiency and cost.

As shoulder arthroscopy is performed with increasing frequency, the associated total cost to society will also increase [9]. Understanding the variable costs associated with set-up time and supply costs will help guide surgeons' decision-making and future cost-reduction efforts [14]. Set-up expenses that differ based on your set-up position add variable expenses to each procedure's overall cost. Although not the primary driving expense, a better understanding of the set-up material costs can influence providers to be more efficient and cost-conscious. Previous studies have shown procedural factors, including the number of anchors, operative time, use of biologics, pre-operative regional blocks, and additional procedures such as distal clavicle resections, open biceps tenodesis, and subacromial decompressions are the main drivers of increasing cost with rotator cuff surgery [15,16]. We carefully reviewed the costs of individual disposable items used during arthroscopic rotator cuff repair cases in both beach-chair and lateral decubitus positions and found the isolated supply costs, or those costs related directly to the patient positioning, were significantly less in the lateral decubitus group compared to the beach chair group ($238 vs. $415).

Supply and implant costs vary based on individual vendor contracts with specific facilities. When calculating the supply costs, we used our institutional costs, not the retail price for supplies and implants. Our two groups had no statistically significant difference in overall total implant cost. However, on average, the beach-chair group had a higher total implant cost per case than the lateral decubitus group ($1,502 vs. $1,152, P=0.053). This increase was due to the surgeon's preference for rotator cuff fixation construct and the number of anchors used. The most effective and least costly way to repair a torn rotator cuff remains controversial [17]. Overall, arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs are a cost-effective procedure [18].

Inappropriate patient positioning is thought to be one of the major causes of complications during arthroscopic shoulder surgery [19-21]. With proper positioning, these complications can be avoided. Regardless of the preferred arthroscopic patient position, the surgeon must ensure appropriate positioning and assist staff to be appropriately trained and aware of potential complications [21]. Three minor complications occurred in the beach-chair position, all superficial infections (1.9%). There were seven minor complications in the lateral decubitus group (5.1%), including two patients who developed hematomas, two patients with complaints of paresthesias in the operative hand due to traction, one patient who complained of numbness in their tongue at their initial post-operative appointment, another who had prolonged swelling in the neck around the site of the pre-operative block site, and one patient who developed a lower extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT) postoperatively. All minor complications were resolved by final follow-up with conservative measures. There was no statistically significant difference in complication rate between the two groups (1.9% vs. 5.1%, P=0.196).

In both beach-chair and lateral decubitus positioning, it is crucial to maintain the cervical spine in a neutral position and avoid excessive pressure on the face and other bony prominences. Other previously documented reports of hypoglossal and superficial nerve palsies were associated with excessive compression and rotation of the head in the beach-chair position. However, the same principles apply to patients in the lateral position [22,23]. A more commonly documented complication in the lateral decubitus position is brachial plexus palsies caused by prolonged traction on the operative arm [21]. Klein et al. [24] reported a reduced incidence of brachial plexus strain when the arm was positioned at 45 degrees of forward flexion and zero and 90 degrees of abduction. For optimal visualization, the operative arm is typically positioned in about 25 to 30 degrees of abduction in the scapular plane with approximately 30 degrees of forward flexion [11]. Care must also be taken with proper portal placement to avoid intraoperative iatrogenic nerve injuries.

One of the major feared and documented complications of beach-chair positioning in shoulder arthroscopy surgery is cerebral hypoperfusion which can lead to ischemic events causing stroke, vision loss, and central nervous system infarcts. There were no reported incidences or noted complications related to cerebral hypoperfusion in our study's beach-chair position patients. Commonly, apprehension with beach-chair position from both anesthesia staff and some surgeons stems from the concern of documented catastrophic events related to cerebral hypoperfusion events. However, these, in general, are rare. Accurately measuring and maintaining appropriate blood pressure intraoperatively and in the perioperative period is required [25]. Koh et al. [26] performed a prospective study on the effect of general and regional anesthesia on cerebral oxygenation and found significantly lower rates of desaturation events with regional and intravenous sedation.

One patient in the lateral decubitus group developed a deep vein thrombosis postoperatively which was treated with appropriate anticoagulative medical therapy. Thromboembolic events are rare following arthroscopic shoulder surgery [11,27]. There are equal reported incidences of thromboembolic events reported in both the beach-chair and lateral decubitus positions [28,29]. Due to the few reported cases, there needs to be more data and evidence on the best strategy for prevention. The risk factors for DVT and pulmonary following shoulder arthroscopy are similar to the general population, including increased age, diabetes mellitus, malignancy, and inherited forms of thrombophilia [30-32].

There were several strengths of this study. Our study is the first to objectively quantify the set-up time and cost for the beach-chair and lateral decubitus positioning for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. It was also performed in a high-volume ASC with experienced staff trained and proficient in both positions. Lastly, a large number of patients in both cohorts allowed our study to be appropriately powered.

There are several limitations to the study. This is a single-center, retrospective study with relatively short-term follow-up. As a single-center study, our results may not be generalized to other facilities and other surgeons. When considering the supply costs, we did not include the initial investment in the Trimano pneumatic arm holder (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) for the beach chair position or the shoulder traction tower (Arthrex, Inc, Naples, FL) for the lateral decubitus position. Timing values in the study were calculated using intraoperative nursing and anesthesia notes. If video recordings in the rooms were available, this could be a more accurate way to verify correct timing throughout the case objectively. Identifying the total cost per rotator cuff repair is complicated as many variables exist. This is also not a comprehensive analysis of the total cost of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. We did not calculate other costs, including anesthesia, operating room personnel, physical therapy, patient time off work, lost income, disability, and other social costs. Additionally, controlling for the number of anchors used and the size of the rotator cuff tear would have helped to strengthen our study further; however, this was outside of the main goals of our study.

5. Conclusion

The results of our study demonstrate that arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in the lateral decubitus position requires decreased time for set-up and has decreased supply costs. Strategies should be implemented to improve efficiency, reduce overall operative time, and lower supply costs. Ultimately, the decision on arthroscopic shoulder positioning should be based on surgeon comfort and training for optimal patient outcomes. Surgeons should be aware of all the advantages and disadvantages of beach-chair and lateral decubitus positions and associated complications. Additional studies are needed to delineate better and understand the financial costs of arthroscopic shoulder surgery.

Acknowledgments:

None

Conflict of Interest:

None

Funding/Sponsorship:

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

IRB Information:

This study was approved by the IRB at OhioHealth Corporation Institutional Review Board. Study number 1227796-18

Authors Contributions:

All authors contributed to data collection, data assimilation, and manuscript preparation.

References

- Weinstein SI, Yelin EH, Watkins-Castillo SI. United States Bone and Joint Initiative: The Burden of Musculoskeletal Diseases in the United States (BMUS), Third Edition, 2014. Rosemont, IL. Available at http://www.boneandjointburden.org. Access on 05/23/2022.

- Tashjian RZ. Epidemiology, natural history, and indications for treatment of rotator cuff tears. Clin Sports Med 31 (2012): 589-604.

- Milgrom C, Schaffler M, Gilbert S, et al. Rotator-cuff changes in asymptomatic adults. The effect of age, hand dominance and gender. J Bone Joint Surg Br 77 (1995): 296-298.

- Sher JS, Uribe JW, Posada A, et al. Abnormal findings on magnetic resonance images of asymptomatic shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Am 77 (1995): 10-15.

- Teunis T, Lubberts B, Reilly BT, et al. A systematic review and pooled analysis of the prevalence of rotator cuff disease with increasing age. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 23 (2014): 1913-1921.

- Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Osawa T, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 19 (2010): 116-120.

- Keener JD, Galatz LM, Teefey SA, et al. A prospective evaluation of survivorship of asymptomatic degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 97 (2015): 89-98.

- Yamaguchi K. Tetro AM, Blam O, et al. Natural history of asymptomatic rotator cuff tears: a longitudinal analysis of asymptomatic tears detected sonographically. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 10 (2001): 199-203.

- Colvin AC, Egorova N, Harrison AK, et al. Nation trends in rotator cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am 94 (2012): 227-233.

- Jensen AR, Cha PS, Devana SK, et al. Evaluation of the trends, concomitant procedures, and complications with open and arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs in the medicare population. Orthop J Sports Med 5 (2017): 2325967117731310.

- Li X, Eichinger JK, Hartshorn T, et al. A comparison of the lateral decubitus and beach-chair positions for shoulder surgery: advantages and complications. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 23 (2015): 18-28.

- Peruto CM, Ciccotti MG, Cohen SB. Shoulder arthroscopy positioning: lateral decubitus versus beach chair. Arthroscopy 25 (2009): 891-896.

- Skyhar MJ, Altchek DW, Warren RF, et al. Shoulder arthroscopy with the patient in the beach-chair position. Arthroscopy 4 (1988): 256-259.

- Chalmers PN, Kahn T, Broschinsky K, et al. An analysis of costs associated with shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 28 (2019): 1334-1340.

- Morris JH, Malik AT, Hatef S, et al. Cost of Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repairs Is Primarily Driven by Procedure-Level Factors: A Single-Institution Analysis of an Ambulatory Surgery Center. Arthroscopy 37 (2021): 1075-1083.

- Solomon DJ. Editorial Commentary: Cost Associated With Arthroscopic Rotator Cuff Repair Can Be Largely Controlled by the Surgeon. Arthroscopy 37 (2021): 1084-1085.

- Black EM, Austin LS, Narzikul A, et al. Comparison of implant cost and surgical time in arthroscopic transosseous and transosseous equivalent rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 25 (2016): 1449-1456.

- Vitale MA, Vitale MG, Zivin JG, et al. Rotator cuff repair: An analysis of utility scores and cost-effectiveness. J Shoulder and Elbow Surg 16 (2007): 181-187.

- Cooper DE, Jenkins RS, Bready L, et al. The prevention of injuries of the brachial plexus secondary to malposition of the patient during surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 228 (1988): 33-41.

- Krishnan SG, Pennington SD, Cooper DE, et al. General complications of arthroscopic shoulder surgery. In: Gill TJ, Hawkins RJ, editors. Complications of Shoulder Surgery: Treatment and Prevention. Philadelphia, PA, Lippincott, Williams, and Wilkins (2006): 125-132.

- Moen TC, Rudolph GH, Caswell K, et al. Complications of Shoulder Arthroscopy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 22 (2014): 410-419.

- Mullins RC, Drez D Jr, Cooper J. Hypoglossal nerve palsy after arthroscopy of the shoulder and open operation with the patient in the beach-chair position: A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 74 (1992): 137-139.

- Park TS, Kim YS. Neuropraxia of the cutaneous nerve of the cervical plexus after shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy 21 (2005): 631.

- Klein AH, France JC, Mutschler TA, et al. Measurement of brachial plexus strain in arthroscopy of the shoulder. Arthroscopy 3 (1987): 45-52.

- Papadonikolakis A, Wiesler ER, Olympio MA, et al. Avoiding catastrophic complications of stroke and death related to shoulder surgery in the sitting position. Arthroscopy 24 (2008): 481-482.

- Koh JL, Levin SD, Chehab EL, et al. Neer Award 2012: Cerebral oxygenation in the beach chair position. A prospective study on the effect of general anesthesia compared with regional anesthesia and sedation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 22 (2013): 1325-1331.

- Triplet JJ, Schuette HB, Cheema AN, et al. Venothromboembolism following shoulder arthroscopy: a systematic review. JSES Rev Rep Tech 2 (2022); 464-468.

- Brislin KJ, Field LD, Savoie FH 3rd. Complications after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. Arthroscopy 23 (2007): 124-128.

- Randelli P, Castagna A, Cabitza F, et al. Infectious and thromboembolic complications of arthroscopic shoulder surgery. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 19 (2010): 97-101.

- Boileau P, Mercier N, Roussanne Y, et al. Arthroscopic Bankart Bristow-Latarjet procedure: The development and early results of a safe and reproducible technique. Arthroscopy 26 (2010): 1434-1450.

- Bongiovanni SL, Ranalletta M, Guala A, et al. Case reports: Heritable thrombophilia associated with deep venous thrombosis after shoulder arthroscopy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 467 (2009): 2196-2199.

- Burkhart SS. Deep venous thrombosis after shoulder arthroscopy. Arthroscopy 6 (1990): 61-63.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 73.64%

Acceptance Rate: 73.64%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks