Efficacy of a Vancomycin/Tobramycin-Doped Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)- Polymeric Dicalcium Phosphate Dehydrate (P-DCPD) Composite for Prevention of Periprosthetic Infection in a Mouse Pouch Infection Model Implanted with 3D-printed Porous Titanium Cylinders

Michael Dubé MD1, Adam Miller MD1, Michael Kaminski MD1, Therese Bou-Akl MD, PhD1,2*, Paula Pawlitz MS1, Weiping Ren MD, PhD1,2,3, David C. Markel MD1,2,4

1Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Henry Ford Providence Hospital, Southfield, MI, USA

2Department of Biomedical Engineering, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, USA

3Virotech Co., Inc., Troy, MI, USA

4The Core Institute, Novi, MI, USA

*Corresponding Author: Therese Bou-Akl MD, PhD, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Henry Ford Providence Hospital, Southfield, MI, USA.

Received: 17 December 2025; Accepted: 29 December 2025; Published: 13 January 2026

Article Information

Citation: Michael Dubé, Adam Miller, Michael Kaminski, Therese Bou-Akl, Paula Pawlitz, Weiping Ren, David C. Markel. Efficacy of a Vancomycin/Tobramycin-Doped Polyvinyl Alcohol (PVA)-Polymeric Dicalcium Phosphate Dehydrate (P-DCPD) Composite for Prevention of Periprosthetic Infection in a Mouse Pouch Infection Model Implanted with 3D-printed Porous Titanium Cylinders. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research. 10 (2026): 28-35.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Prosthetic joint infection (PJI) is a challenging problem with current techniques including irrigation and antibiotics having limited effectiveness. This study evaluated the effect of antibiotic doped polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)- polymeric dicalcium phosphate dehydrate (P-DCPD) composite on prevention of PJI in a mouse pouch model implanted with porous titanium (Ti) cylinders. Air pouches were created in 30 mice (n=10 within each group). Pouches were implanted with either porous Ti cylinders only (negative control), Ti cylinders and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (positive control), or Ti cylinders pre-doped with antibiotic-loaded PVA-P-DCPD and S. aureus (treatment group). At sacrifice, mouse washings and Ti cylinders were collected for bacterial analysis. There were no detectable bacteria in the washings or cylinder sonicate following implantation with antibiotic doped PVA-PDCPD or in the negative controls. Bacteria were present in the washings of the positive control (1894 ± 2455 cfu/ml) which was significant compared to the treatment group (P< 0.001). Similarly, Ti discs had significantly lower bacterial counts in the treatment group when compared to positive controls (0 cfu/ml vs 22233 ± 33735 cfu/ml, P=0.002). Pre-treatment of titanium implants with Vancomycin and Tobramycin doped PVA-P-DCPD led to a significant reduction in bacterial load which may represent an effective means of preventing PJI in the future.

Keywords

<p>Saline irrigation; PVA-VAN/TOB-P-DCPD bioceramic composite; Mouse pouch infection model; Vancomycin; Infections</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Various strategies have emerged to prevent or eliminate implant-associated bacterial infections with differing levels of success. Antibiotics in the perioperative setting and saline irrigation are commonly used methods for bacterial growth prevention [1,2]. However, in the presence of bacteria, particularly those associated with biofilm formation, irrigation alone is generally not effective at preventing ongoing bacterial growth. Other strategies to prevent infection involve modification of the physiochemical properties of the implants themselves to achieve potential bactericidal effects, bacterial anti-adhesion, and enhanced osteointegration [3,4]. Techniques such as electrodeposition of silver and shockwave application of biopolymers have shown promise [5,6].

Porous titanium (Ti) implants have emerged as important devices for joint arthroplasty due to their excellent biocompatibility and mechanical strength [7]. The implants are designed to promote osteointegration and provide a 3D structure for fibroblasts, osteoblastic cells, and mesenchymal stem cells to promote long-term orthopedic implant success [8,9]. Enhanced osseointegration and healing is promoted through enhanced surface chemistry, surface topography, and surface wettability [9]. As such, porous Ti implants have become one of the most popular materials used in orthopaedics [10].

The same implant properties that make porous Ti components popular also predispose susceptibility to bacterial colonization and proliferation [11]. Polymicrobial biofilm formation has been identified as the main risk factor for inflammatory processes surrounding the implant [12]. Staphylococcus, specifically, accounts for up to two thirds of all pathogens found in orthopaedic surgery periprosthetic joint infections (PJI) [13]. If not adequately prevented or treated, PJI may lead to revision, amputation, and even death [13]. Thus, it is imperative to develop effective strategies to combat bacterial threats and prevent infection while preserving the implant's ability to integrate with bone [3].

One promising approach to preventing/treating PJI involves a polymeric substrate pre-loaded with antibiotics and applied to the implant surface or into the porous structure of the orthopedic device [14,15]. The addition of this material into/onto the prosthesis surfaces acts as a reservoir that may release antibiotics locally to prevent bacterial growth, while preserving the biomechanical properties of the implant or prosthesis [16]. Polymeric dicalcium phosphate dehydrate (P-DCPD) was developed as an alternative to poly(methyl methacrylate) (PMMA) for antibiotic delivery in orthopaedic implants [17]. P-DCPD allows for sustained antibiotic release without compromising mechanical strength when compared to classic DCPD [17]. Polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) is a known water-soluble polymer. PVA hydrogel represents a promising fast degrading matrix for drug release because of its biocompatibility and proven mechanical strength [14]. The fast degradation results in rapid antibiotic release from the material. A combination paste material was developed by embedding Vancomycin and Tobramycin (Van/TOB)-doped P-DCPD powders into a PVA gel matrix. The new material, VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD, therefore has the capability of delivering antibiotics in a biphasic and sustained pattern to reduce bacterial load [14,17].

There is no consensus regarding the most beneficial antimicrobial agent or coating for prevention or treatment of PJI and the impact of PJI remains significantly detrimental to orthopaedic surgery patients worldwide. Therefore, the purpose of this study was to evaluate Vancomycin/Tobramycin doped PVA-P-DCPD (VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD) on infection treatment and prevention as well as the subsequent inflammatory and toxicity profile in a S. aureus mouse pouch infection model implanted with 3D printed porous Ti cylinders that utilized a manufacturing process identical to that used in commercial total joint arthroplasty (TJA) products.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Materials

The study utilized 30 female BALB/cJ strain mice (Charles River Laboratory, Wilmington, MA) and Kanamycin resistant XN29 S. aureus bacteria (Xenogen 29, Caliper Life Science, Hopkinton, MA).

2.2 Preparation of antibiotic-doped PVA/ceramic composite paste

Calcium polyphosphate (CPP) gel and tetra-calcium phosphate (TTCP) were prepared as previously described [18]. P-DCPD ceramics were prepared by mixing CPP gel with TTCP at room temperature for setting [18]. P-DCPD ceramics were doped with 10% of both VAN and TOB (VAN/TOB-P, wt/wt) by mixing the drugs with CPP gels before adding TTCP for setting. PVA powders were then dissolved in distilled water and heated at 90oC for 6 hours (w/v, g/ml) to create 7.5% PVA gel. The VAN/TOB- PVA-P-DCPD composite pastes were prepared by adding P-DCPD fine particles into the PVA gel and mixed with stirring. The ratio of PVA gel/= to P-DCPD particles was 2:1. The combined VAN/TOB doped PVA-P-DCPD composite pastes were stored at -20oC before using.

2.3 Preparation of Ti Cylinders

Printed 3D Ti cylinders were manufactured and provided by Stryker (Stryker Orthopaedics, Mahwah, NJ, USA). The additive manufacturing used the same processes as Stryker’s commercial products. The 4mm x 4mm cylinders were printed with a defined 400 µm pore size. The cylinders were washed in 70% ethanol for one hour, followed by a wash in distilled water for an hour while stirring. Before use the cylinders were sterilized by heat and pressure trough autoclaving.

2.4 Ti Cylinders with VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite paste coating

The sterilized Ti cylinders were coated with the VAN/TOB doped PVA-P-DCPD composite paste by manual pressing. The cylinders were weighed before and after coating to provide an accurate measurement of how much composite paste was loaded to calculate the amount of antibiotics within the cylinder. The amount of antibiotic within the cylinders was an average of 0.07g (0.05g – 0.07g). The coating was performed on site just before implantation and would therefore simulate a precoating of a press fit implant.

2.5 Experimental Design

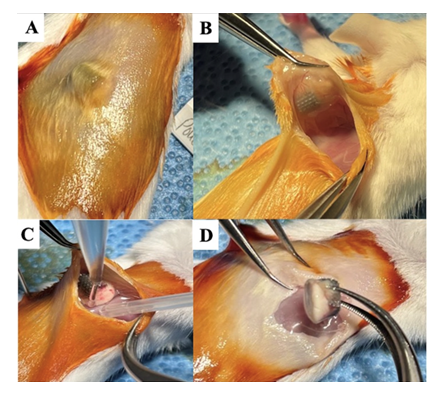

The study was approved by our Animal Care Committee and the Laboratory Animal Administration. The thirty female BALB/cJ mice were randomly divided into three groups. Air pouches were created on the back of the mice by subcutaneous injections of 1.5ml of sterile air two to three times within one week (n=10 per group) as previously described by Wooley et al. [19] After seven days, mice with established air pouches were anesthetized using an intraperitoneal injection of a mixture of Xylazine (10 mg/kg) and Ketamine (120 mg/kg). A 0.5-1 cm incision was then made over the pouch area, and the pouch membrane was cut to open the pouch for the placement of the Ti cylinders (Figure 1). Group I received porous Ti cylinders only (negative control), group II received porous Ti cylinders and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus (1X106 colony forming units (cfu)) (positive control), and Group III received Ti cylinders preloaded with VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite and S. aureus (1x106 cfu) (treatment group). The pouch layers and skin wounds were sealed using skin glue.

Figure 1: Gross images of surgical steps of the pouch cavity with saline wash and implant harvest 28 days after Ti cylinder implantation and bacterial inoculation. (A) Air pouch cavity with Ti cylinder visible inside. (B) Pouch cavity open with Ti cylinder visible inside. (C) Pouch cavity washout with saline and collection of washing. (D) Harvest of the Ti cylinder.

2.6 Post-Operative Care

Post-surgery, mice were housed in cages warmed by a water circulating heating blanket and then transferred to individual cages once the anesthetic effects had subsided. They were monitored for signs of infection and delayed wound healing for one week following surgery. The mice were scheduled for euthanasia 28 days post-implantation. Immediately after sacrifice each pouch was opened and with the implant in place, the pouch was washed with 3ml of saline and the wash out collected for analysis, then the implant retrieved for culture.

2.7 Histological and Bacterial Analysis

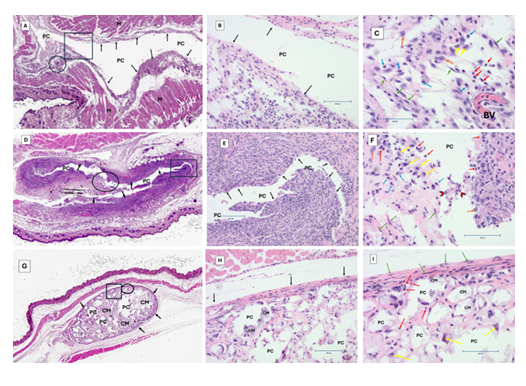

After sacrificing the mice, pouch tissues were harvested and fixed in 10% buffered neutral formalin (BNF) and processed for histology by creating 5 µm sections stained with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E) (Figure 2). Stained tissues were scanned using the PathScan Pro slide system and higher resolution images were taken using the Spot software. Liquid bacterial cultures from the pouch washouts were grown in the presence of kanamycin on agar plates and colonies were counted to determine bacterial quantity.

2.8 Analytical Techniques for Implanted Cylinders

The Ti Cylinders were sonicated three times for five minutes in tubes containing sterile saline. After each sonication, cylinders were transferred to a new tube, and samples from each sonicate were plated on agar plates containing kanamycin for bacterial quantification. Following sonication, the Ti cylinders were cultured on kanamycin agar plates to determine if any bacteria remained embedded in the disks.

2.9 Outcome Measurements

Systemic toxicity was evaluated through observation of physical or behavioral changes such as impaired wound healing, uneasiness, lack of eating, and/or decreased activity.

2.10 Data analyses

Data obtained from the pouch washes and retrieved implants were analyzed using appropriate statistical methods, including analyses of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey post hoc tests when ANOVA returns a P <0.05, to assess the differences between groups and the efficacy of the treatments. Statistical significance was set at P<0.05.

3. Results

3.1 Bacterial Growth

Data From the pouch washings, the treatment group (VAN/TOB-doped PVA-P-DCPD) had no detectable bacteria (0 cfu/ml). Similarly, there were no detectable bacteria in the negative control group (0 cfu/ml). In contrast, in the positive control group (S. aureus and Ti cylinders without the Antibiotic loaded PVA-P-DCDP), there was significant bacterial presence, with an average of 1,894 ± 2,455 cfu/ml. There were clearly significant differences between the treatment (0 cfu/ml) versus the non-treatment group (1894 ± 2455 cfu/ml) (P<0.001) (Table 1).

In the Ti cylinder sonicates, the treatment group again had no detectable bacteria on the Ti cylinders (0 cfu/ml). The findings were similar to the negative controls (0 cfu/ml). The untreated Ti cylinders (positive control group) had high bacterial counts, with an average of 22,233 ± 33,735 cfu/ml. The difference between the groups was highly significant (P=0.002) (Table 1).

|

WASH |

||

|

Group |

Group |

p-value |

|

Ti cylinder only (0 cfu/ml) |

Bacteria + Ti cylinder (1894 ± 2455 cfu/ml) |

<0.001 |

|

Ti cylinder only (0 cfu/ml) |

Bacteria + Ti cylinder + antibiotic doped P-DCPD (0 cfu/ml) |

1.000 |

|

Bacteria + Ti cylinder (1894 ± 2455 cfu/ml) |

Bacteria + Ti cylinder + antibiotic doped P-DCPD (0 cfu/ml) |

<0.001 |

|

CUMULATIVE SONICATE |

||

|

Group |

Group |

p-value |

|

Ti cylinder only (0 cfu/ml) |

Bacteria + Ti cylinder (22233 ± 33735 cfu/ml) |

0.002 |

|

Ti cylinder only (0 cfu/ml) |

Bacteria + Ti cylinder + antibiotic doped P-DCPD (0 cfu/ml) |

1.000 |

|

Bacteria + Ti cylinder (22233 ± 33735 cfu/ml) |

Bacteria + Ti cylinder + antibiotic doped P-DCPD (0 cfu/ml) |

0.002 |

Table 1: Turkey HSD Post Hoc test. Mean bacterial amount with 95% confidence intervals in parentheses below group name. Significance set at P<0.05.

Figure 2: H&E-stained images of all conditions. (A, D, G) represent scanned images of whole slide. (B, E, H) are representative images with 10X magnification, scale bar 100 microns. (C, F, I) are representative images with 20X magnification, scale bar 100 microns. Group 1 (negative control-A, B, C). Group 2 (positive control-D, E, F). Treatment group (PDCDD with antibiotics- G, E, I). Labels on the figure: (PC) Pouch cavity, (M) muscles, black arrows indicate pouch capsule, green arrows (fibroblasts), red arrows (lymphocytes), cyan arrows (monocytes), yellow arrows (macrophages), orange arrows (granulocytes) and chevron arrows points at polymorphonuclear (PMN) leucocytes. Square shape (inset for 10x magnification), circle (inset for 20x magnification).

3.2 Histological Analyses

Histological examination showed varying degrees of inflammation in the pouch tissues (Figure 2). The tissues from the treatment group showed minimal inflammation and no signs of bacterial colonies or biofilm formation. Tissues from the positive control group exhibited moderate to severe inflammation, with visible bacterial colonies and biofilm formation. The negative control group, as expected, displayed normal tissue morphology with mild inflammation due to the presence of the implant.

3.3 Systemic Toxicity and Physical Health

Mice in the treatment and negative control groups displayed normal behavior and activity levels. Three out of ten mice in the positive control group exhibited signs of discomfort as the implant had migrated into the adjacent subcutaneous tissue.

4. Discussion

PJI remains problematic and research into its treatment is of great importance. This study found that the use of a VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite significantly reduced bacterial load in porous coated Ti implants and effectively eradicated S. aureus infection (0 cfu/ml). The same VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite used in this study was previously shown to be effective at decreasing bacterial load in a rat knee S. aureus infection model with implanted porous Ti discs [20]. In that model, the VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite was used as a treatment choice after saline irrigation of the infected joint with the implant in place. Two weeks after the treatment, bacterial analysis of both the collected joint fluid and the implants demonstrated significant decrease in bacterial burden [20]. The results of our current study further confirm that a pre-coated antibiotic loaded PVA-P-DCPD composite is efficacious at decreasing bacterial burden on infected orthopaedic implants and may also be used to prevent the occurrence of infection.

While porous Ti implants are used in TJA for their osseointegrative properties [7-10], the porous surface also provides a surface for bacterial ingrowth and ongrowth and resultant infection [11]. PJI is a devastating complication of TJA, which makes methods of treatment and prevention of paramount importance. Historically, saline irrigation has been used as a preventative method in eradication of bacterial growth. However, multiple studies have shown that the use of a saline-only irrigation protocol in periprosthetic bacterial infection has limited effect with a persistence of bacterial infection despite its use [14]. To enhance irrigation efficacy, the inclusion of potent bactericidal chemicals has been necessary, and the intraoperative use in combination with normal saline has become a common and effective approach to control bacterial growth. A potential downside of the use of these additive chemicals is that they can result in cytotoxic tissue effects, potentially affecting implant success and patient recovery. Studies evaluating commonly used bactericidal irrigation solutions supported their effectiveness at eradicating bacteria, but also demonstrated increased soft-tissue edema, inflammation, and necrosis [1]. Thus, emphasizing the need for the careful selection of irrigation solutions and, more importantly, underscoring the limitations of traditional bacterial prevention methods utilized in orthopaedic surgery.

Recently, there has been an increased emphasis on implant materials, as well as the coating on the surface of the prothesis, as it relates to bacterial infection. Malhotra et al. [21] studied the impact of commonly used orthopaedic metal implant materials on bacterial adhesion and found that the highest level of adherence was on highly cross-linked polyethylene with the lowest adherence on cobalt-chromium alloy. Implant size can also affect the level of bacterial adherence as found in a previous study comparing 400, 700, and 1,000 µm titanium cylinders [22]. A substantial infection was observed only in pouches with 400 µm cylinders as evidenced by severe tissue inflammation and necrotic pouch membrane zones [22]. These were the same sized cylinders used in a previous study and may have provided a more accurate representation of the efficacy of antibiotic loaded PVA-P-DCPD due to ability to overcome greater bacterial infection susceptibility [22]. Cylinders with 400 µm pore size were also used in our study because they are commonly found among implants in a clinical setting and demonstrate real world application. Also, because these cylinders are more susceptible to infection, an inhibition or decrease in bacterial growth utilizing the VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite would demonstrate a larger impact compared to the use of other cylinders not as susceptible to infection. Additionally, surface factors such as roughness, chemical structure, hydrophilicity, and surface free energy have all been identified as having an influence on bacterial adherence and growth [23,24]. The results from these previous studies regarding implant material illustrate the complex interplay of material surface structure on bacterial growth. Thus, it is very unlikely that any one combination of surface properties would prevent all bacterial growth under all conditions. This highlights the need for comprehensive strategies such as the use of a PVA-P-DCPD composite to further reduce infection risk, infection prevention, and improve orthopedic implant success.

Antibiotic coatings and modifications to implants have been of recent interest given increasing recognition of biofilm formation in the occurrence of PJI [25]. Stavrakis et al. previously studied the use of a biodegradable composite containing tigecycline and vancomycin in a mouse model [26,27]. Like our study, the authors found that the delivery of antibiotics decreased the rate of infection as well as overall bacterial growth on the implant itself. Min et al. also found a decreased bacterial load in a rabbit model for prostheses coated with a hydrolytically degradable multilayer delivering antibiotics, specifically gentamicin. Various composites and polymers, including P-DCPD as used in our study, have been used to incorporate these antibiotics within the prosthetic implant.

P-DCPD itself has been recently studied for its ability to release antibiotics and retain bactericidal activity while maintaining mechanical strength [17]. Ren et al. [17] studied the use of Vancomycin and Tobramycin loaded P-DCPD and found high bactericidal efficacy against S. aureus. They concluded that not only is the bactericidal activity of the antibiotics dependent on the amount of antibiotics released but also on the amount adhered on the surface of the degrading cement [17]. Of note, Ren et.al also found significant differences between the percentage release of VAN and TOB from the P-DCPD. The initial release of VAN was rapid <30% within the first 3 days and 76% of it was released by the end of the study(28 days). When TOB was added (VAN/TOB-P-DCPD), >90% of VAN was released within 3 days (p < 0.05). The percentage release of TOB was very low (<5%) when used alone and <1% when combined with VAN over 28 days [17]. The results of our study provide further evidence for the utility of Vancomycin and Tobramycin loaded P-DCPD in infection prevention.

Vancomycin and Tobramycin, specifically, have also shown to be efficacious in preventing implant infection in biocomposites other than P-DCPD. Markel et al. [14] studied the use of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA)/bioceramic composites impregnated with Vancomycin alone or in combination with Tobramycin. Similar to our study, the results showed that the addition of Vancomycin/Tobramycin PVA/bioceramic composite successfully eliminated S. aureus in mouse pouch washouts and mouse pouch tissues compared to persistent growth after saline irrigation alone [14]. Vancomycin and Tobramycin have also been more recently used in powdered form to prevent surgical site infections in multiple different orthopaedic areas and specialties. Recently, Pesante et al. determined that Vancomycin and Tobramycin powders decrease the rate of deep surgical site infection in open fracture treatment [28].

Some implant coatings have been found to increase susceptibility to bacterial colonization secondary to increased surface roughness and hydrophobicity [29]. However, many modern coatings are specifically engineered to reduce bacterial adhesion and biofilm formation [30]. Additional methods other than antibiotic coatings that have been studied in combating bacterial colonization and preventing PJI in patients include the use of different polymer coatings such as chitosan, metal ions, peptide-based coatings as well as multifunctional and smart coatings [31]. Soma et al. [29] implanted silver-coated titanium rods in mice femoral bone and found significantly inhibited P. gingivalis infection with silver-coated compared with non-coated rods. However, silver can also exert toxic effects on eukaryotic cells in the immediate vicinity of the coated implants as well as systemically throughout the body.

The P-DCPD composite used in our study has been previously shown to be non-toxic to surrounding tissues based on histological analyses demonstrating eradication of inflammation with no inferior impact on osteoblastic cells [17,23]. Furthermore, Vancomycin and Tobramycin have been shown to be the least cytotoxic antibiotics based on in vitro osteoblastic cell viability studies. Our results provide further evidence regarding the non-toxic nature of the VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite. The treatment group showed normal behavior and activity levels as well as minimal inflammation of the tissues that were analyzed. Conversely, the tissues from the positive control group exhibited moderate to severe inflammation, demonstrating the non-toxic nature provided with the addition of the VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite. Although the structure and physiochemical makeup of VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite is less studied than some other coatings, P-DCPD is natural in composition (calcium and phosphate), has adequate mechanical strength, and could distribute antibiotics with anti-washout properties [14,17]. Thus, the precoat would help provide initial fixation, encourage boney ingrowth (long-term fixation), and prevent infection. Chen et al. previously concluded that DCPD coating significantly improves cancellous bone ingrowth when used on titanium implants in an ovine bone model.

This study is not without limitations. A mouse pouch model was used for the study opposed to a bone implant model which does not fully reflect the true environment of orthopaedic implants. Additionally, the pouch washings were obtained after 28 days compared to distinct time points in smaller increments prior to euthanizing the mouse. Thus, we were unable to measure the drug release profile of the antibiotics in terms of the velocity and length of drug release. However, a previous study showed the elution profiles of the antibiotics VAN and TOB from the VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD composite as having a biphasic phase release profile, with initial early and burst release (mainly from PVA gel) followed by sustained release (from slow-degrading embedded PDCPD particles) up to 30 days [17]. The concentrations of VAN and TOB released were maintained above the minimum biofilm eradication concentration (> 200 ug) for that elution period. Furthermore, only one bacterial strain (S Aureus) was used which somewhat limits the scope of possible use for orthopaedic hardware. However, it is important to note that coagulase negative Staphylococcus species have previously been shown to be the leading cause of PJI. Lastly, although previous studies have commented on bony ingrowth of P-DCPD, this study focused on the effect of the composite on the prevention of infection in an air pouch model which is not suitable for testing osseous integration.

5. Conclusions

Porous Ti implants are vulnerable to bacterial infection and biofilm formation, which may lead to prosthetic joint infections and further complications. In our mouse model, air pouches were implanted with either porous Ti cylinders only (negative control), Ti cylinders and Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (positive control), or Ti cylinders preloaded with antibiotic-loaded PVA-P-DCPD and S. aureus (treatment group). The porous titanium cylinders containing staphylococcus aureus and pre-treated with Vancomycin and Tobramycin doped PVA-P-DCPD had significantly less bacterial load in the washings and titanium discs. Additionally, the treatment group showed minimal inflammation and no signs of bacterial colonies or biofilm formation. Therefore, VAN/TOB-PVA-P-DCPD used as an implant precoat may represent an effective means of treating or preventing PJI. However, further studies evaluating its efficacy are warranted to determine real world utility and application in TJA or other orthopaedic surgeries.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgments.

Conflicts of Interest

Author David Markel has the following disclosures: he received Royalties from Smith-Nephew and owns stocks in HOPco, Plymouth Capital, Arboretum Ventures. He has been involved as a consultant and expert witness in the company Smith-Nephew and the company Stryker. Author Weiping Ren has the following disclosures: he is the founder of Virotech Co., Inc., and the inventor of patent titled “Device and method for electrospinning multiple layered and three dimensional nanofibrous composite materials for tissue engineering”. USA patent US 9,803,294 B1; Date of Patent: 31 October 2017. The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Markel JF, Bou-Akl T, Dietz P, et al. The Effect of Different Irrigation Solutions on the Cytotoxicity and Recovery Potential of Human Osteoblast Cells In Vitro. Arthroplast Today 7 (2021): 120-125.

- Smith DC, Maiman R, Schwechter EM, et al. Optimal Irrigation and Debridement of Infected Total Joint Implants with Chlorhexidine Gluconate. J Arthroplasty 30 (2015): 1820-1822.

- Liu Z, Liu X, Ramakrishna S. Surface engineering of biomaterials in orthopedic and dental implants: Strategies to improve osteointegration, bacteriostatic and bactericidal activities. Biotechnol J 16 (2021).

- Wildemann B, Jandt KD. Infections @ Trauma/Orthopedic Implants: Recent Advances on Materials, Methods, and Microbes—A Mini-Review. Materials (Basel) 14 (2021).

- Busscher HJ, Van Der Mei HC, Subbiahdoss G, et al. Biomaterial-associated infection: locating the finish line in the race for the surface. Sci Transl Med 4 (2012).

- Schulze M, Fobker M, Puetzler J, et al. Mechanical and microbiological testing concept for activatable anti-infective biopolymer implant coatings. Biomaterials Advances 138 (2022).

- Kapat K, Srivas PK, Rameshbabu AP, et al. Influence of Porosity and Pore-Size Distribution in Ti6Al4V Foam on Physicomechanical Properties, Osteogenesis, and Quantitative Validation of Bone Ingrowth by Micro-Computed Tomography. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 9 (2017): 39235-39248.

- Feller L, Jadwat Y, Khammissa RAG, et al. Cellular responses evoked by different surface characteristics of intraosseous titanium implants. Biomed Res Int 2015 (2015).

- Markel DC, Dietz P, Provenzano G, et al. Attachment and Growth of Fibroblasts and Tenocytes Within a Porous Titanium Scaffold: A Bioreactor Approach. Arthroplast Today 14 (2022): 231-236.e1.

- Tapscott DC, Wottowa C. Orthopedic Implant Materials. StatPearls (2023).

- Ren WP, Song W, Esquivel AO, et al. Effect of erythromycin-doped calcium polyphosphate scaffold composite in a mouse pouch infection model. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 102 (2014): 1140-1147.

- Bozic KJ, Kurtz SM, Lau E, et al. The epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. Clin Orthop Relat Res 468 (2010): 45-51.

- Souza GS, Bertolini MM, Costa RC, et al. Targeting implant-associated infections: titanium surface loaded with antimicrobial. iScience 24 (2021): 102008.

- Ribeiro M, Monteiro FJ, Ferraz MP. Infection of orthopedic implants with emphasis on bacterial adhesion process and techniques used in studying bacterial-material interactions. Biomatter 2 (2012): 176.

- Markel DC, Todd SW, Provenzano G, et al. Mark Coventry Award: Efficacy of Saline Wash Plus Antibiotics-Doped Polyvinyl Alcohol Composite in a Mouse Pouch Infection Model. J Arthroplasty 37 (2022): S4-S11.

- Tiwari A, Sharma P, Vishwamitra B, et al. Review on Surface Treatment for Implant Infection via Gentamicin and Antibiotic Releasing Coatings. Coatings 11 (2021): 1006.

- Zhou Z, Seta J, Markel DC, et al. Release of vancomycin and tobramycin from polymethylmethacrylate cements impregnated with calcium polyphosphate hydrogel. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 106 (2018): 2827-2840.

- Ren EJ, Guardia A, Shi T, et al. A distinctive release profile of vancomycin and tobramycin from a new injectable polymeric dicalcium phosphate dihydrate cement. Biomed Mater 16 (2021).

- Song W, Seta J, Kast RE, et al. Influence of particle size and soaking conditions on rheology and microstructure of amorphous calcium polyphosphate hydrogel. J Am Ceram Soc 98 (2015): 3758-3769.

- Ren W, Song W, Yurgelevic S, et al. Setting mechanism of a new injectable dicalcium phosphate dihydrate forming cement. J Mech Behav Biomed Mater 79 (2018): 226-234.

- Wooley PH, Morren R, Andary J, et al. Inflammatory responses to orthopaedic biomaterials in the murine air pouch. Biomaterials 23 (2002): 517-526.

- Aboona F, Bou-Akl T, Miller AJ, et al. Effects of Vancomycin/Tobramycin-Doped Ceramic Composite in a Rat Femur Model Implanted with Contaminated Porous Titanium Cylinders. J Arthroplasty 39 (2024): S310-S316.

- Chatterji R, Bou-Akl T, Wu B, et al. Common Wound Irrigation Solutions Produce Different Responses in Infected vs Sterile Host Tissue: Murine Air Pouch Infection Model. Arthroplast Today 18 (2022): 130-137.

- Markel DC, Bergum C, Wu B, et al. Does Suture Type Influence Bacterial Retention and Biofilm Formation After Irrigation in a Mouse Model? Clin Orthop Relat Res 477 (2019): 116-126.

- Malhotra R, Dhawan B, Garg B, et al. A Comparison of Bacterial Adhesion and Biofilm Formation on Commonly Used Orthopaedic Metal Implant Materials: An In Vitro Study. Indian J Orthop 53 (2019): 148-153.

- Markel DC, Bou-Akl T, Wu B, et al. Efficacy of a saline wash plus vancomycin/tobramycin-doped PVA composite in a mouse pouch infection model implanted with 3D-printed porous titanium cylinders. Bone Joint Res 13 (2024): 622-631.

- Guardia A, Shi T, Bou-Akl T, et al. Properties of erythromycin-loaded polymeric dicalcium phosphate dihydrate bone graft substitute. J Orthop Res 39 (2021): 2446-2454.

- Akshaya S, Rowlo PK, Dukle A, et al. Antibacterial Coatings for Titanium Implants: Recent Trends and Future Perspectives. Antibiotics 11 (2022).

- Soma T, Iwasaki R, Sato Y, et al. An ionic silver coating prevents implant-associated infection by anaerobic bacteria in vitro and in vivo in mice. Sci Rep 12 (2022): 1-11.

- Diez-Escudero A, Hailer NP. The role of silver coating for arthroplasty components. Bone Joint J 103-B (2021): 423-429.

- Barua R, Daly-Seiler CS, Chenreghanianzabi Y, et al. Comparing the physicochemical properties of dicalcium phosphate dihydrate and polymeric dicalcium phosphate dihydrate cement particles. J Biomed Mater Res B Appl Biomater 109 (2021): 1644-1655.

Impact Factor: * 5.8

Impact Factor: * 5.8 Acceptance Rate: 71.20%

Acceptance Rate: 71.20%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks