Induced Antileukemic Activity after Blast Modulation is Independent from Immune Checkpoint Marker Expression on Patients’ Blasts or T Cells

Carina Amend1,2,*, Melanie Weinmann1,2, Daniel Christoph Amberger1,2,3, Christoph Schwepcke1,2, Fatemeh Doraneh-Gard1,2, Doris Maria Krämer4, Christoph Schmid2,5, Andreas Rank2,5, Helga Maria Schmetzer1,2,*

1WG Immune Modulation, Medical Department III, University Hospital of Munich, 81377 Munich, Germany

2Bavarian Cancer Research Center (BZKF); Comprehensive Cancer Center at University Hospital of Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany

3First Department of Medicine, Paracelsus Medical University, Salzburg, Austria

4Department of Hematology, Oncology and Palliative Care, St.-Josef-Hospital Hagen, Hagen, Germany

5Department of Hematology and Oncology, University Hospital of Augsburg, Augsburg, Germany

*Corresponding author: Carina Amend, WG Immune Modulation, Medical Department III, University Hospital of Munich, Munich, Germany Helga Maria Schmetzer, WG Immune Modulation, Medical Department III, University Hospital of Munich, Munich, Germany

Received: 18 November 2025; Accepted: 24 November 2025; Published: 18 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Carina Amend, Melanie Weinmann, Daniel Christoph Amberger, Christoph Schwepcke, Fatemeh Doraneh-Gard, Doris Maria Krämer, Christoph Schmid, Andreas Rank, Helga Maria Schmetzer. Induced Antileukemic Activity after Blast Modulation is Independent from Immune Checkpoint Marker Expression on Patients’ Blasts or T Cells. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research. 9 (2025): 521-541.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Acute myeloid leukemia is still associated with a poor prognosis. New therapeutic strategies are necessary. Myeloid leukemic blasts can be converted into dendritic cells (DC) of leukemic origin leukemiaderived DC (DCleu) using ‘DC-generating Picis’ or ‘DC-generating Kits’, resulting in enhanced leukemia-specific antileukemic immune responses.

Methods: DC/DCleu were generated out of leukemic Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMNC) or whole blood (WB) using DC/DCleu- generating protocols and used to stimulate T cell enriched immunoreactive cells in mixed-lymphocyte culture (MLC), followed by a cytotoxicity fluorolysis assay (CTX). We evaluated the expression profiles of immune checkpoint molecules (CD279 (PD-1), CD273 (PD-L2) and CD274 (PDL1)) on uncultured blasts and T cells from AML patients respectively on monocytes and T cells from healthy donors after MLC with Kit pre-treated WB and correlated immune checkpoint (CP) expressions with patients’ clinical data and functional cytotoxicity.

Results: We were able to generate DC/DCleu from leukemic (and healthy) PBMNC and WB without induction of blast proliferation. Stimulation of immunoreactive cells after MLC with Kit pre-treated DC/DCleu containing WB resulted in downregulated CP expression on blasts and DCleu and in increased anti-leukemic cytotoxicity. CP expressing T cells (T279+) correlated negatively with response to induction therapy and with improved blasts lysis ex vivo (T274+).

Conclusion: Through this immunomodulatory approach, we demonstrated the potential to induce or enhance leukemia-specific and anti-leukemic activity ex vivo, largely independent of checkpoint inhibitor expression on blasts, T cells, or patients’ clinical characteristics. Building on these findings, our data further suggest that DC/DCleu could be generated ex vivo using ‘DCgenerating Picis’ or ‘DC-generating Kits’ for subsequent adaptive transfer to patients, or that in vivo treatment with Kit-M could be explored to help stabilize remissions in AML patients.

Keywords

<p>Acute myeloid leukemia; Immune checkpoint molecules; Leukemia derived dendritic cells; Anti-leukemic functionality</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

1.1 Classification and Diagnosis of AML

Acute myeloid leukemia (AML) is characterized by uncontrolled proliferation of myeloid progenitor cells (‘blasts’) in the bone marrow (BM) and peripheral blood (PB), leading to suppression of normal haematopoiesis and resulting in anaemia, bleeding, infections and impaired antitumor immune response [1]. Diagnosis is based on cytomorphological, cytogenetic, molecular and immunophenotypic analyses, which allows for subtyping and prognostic classification of cases [2-4]. The French-American-British (FAB) and WHO classifications divide into subtpyes M0 – M7, while the ELN risk classification enables prognostic subgrouping in ‘favorable’, ‘intermediate’ and ‘adverse’ risk [2].

1.2 Treatment strategies for AML patients (pts)

Standard therapy consists of high-dose cytarabine plus anthracycline chemotherapy, followed by hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT) in younger pts or treatment with hypomethylating agents, often combined with venetoclax [2,5-7]. Although remissions reach up to 80%, most pts relapse within two years, resulting in an unsatisfying prognosis with a 5-year-survival rate of 31.9% [8]. Relapse is driven by residual blasts and/or immune evasion through inhibition of effector T cells, natural killer cells (NK cells) and dentritic cells [9].

Novel therapeutic approaches aim to overcome immune evasion and trigger tumor-specific immune response, e.g. by epigenetic modulation, targeting immune checkpoint molecules or employing antibody-based or cellular immunotherapies (CAR-T cells, NK cells, DC-based strategies) [2,10]. DC-based strategies have the competence to prime and enhance (leukemia-specific) immune responses by presenting individual patients’ whole leukemic antigen repertoire and inducing immunological memory [11,12].

1.3 Dendritic cells (DC) and leukemia-derived DC (DCleu)

DC are potent antigen-presenting cells that stimulate and regulate immune responses. They can be generated from patients’ monocytes and loaded with leukemic antigens. Moreover leukemic blasts from Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMNC) or whole blood (WB) can be converted into leukemia-derived DC (DCleu), expressing DC antigens as well as leukemia-associated antigens. DC/DCleu were generated using specific response modifiers in accordance with established DC/DCleu-generating protocols. Different compositions of response modifiers were employed during this process, including the so-called ‘DC-generating Picis’ (Pici1 (GM-CSF, IL-4, Picibanil and PGE1) or Pici2 (GM-CSF, IL-4, Picibanil and PGE2)) or ‘DC-generating Kits’ (Kit-I (GM-CSF and OK-432), Kit-K (GM-CSF and PGE2) or Kit-M (GM-CSF and PGE1)) [13], without the induction of blast proliferation [14,15]. Experimental data from leukemic rat models and clinical applications in refractory AML patients before or after alloHSCT indicate that in vivo DC/DCleu induction can activate leukemia-specific immune responses and promote disease stabilization [16,17]. DC/DCleu thus enhance ‘graft-versus-leukemia’ (GvL) effects and establish leukemia-specific immunologic memory [10-13,18].

1.4 Immune checkpoint molecules

Immune checkpoint molecules (CP) regulate immune responses by balancing T and NK cell activation [19-21]. While essential for maintaining self-tolerance, they also modulate immune reactions against pathogens or tumors [20,22,23].

CD279 (PD-1), expressed on activated T, B, NK and antigen-presenting cells, interacts with two main ligands CD273 (PD-L2) and CD274 (PD-L1) [24-26]. CD273 and CD274 are found on antigen-presenting, hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic cells and on the surface of tumor cells [27,28]. Engagement of CD279 with these ligands inhibits cytokine production, reduces T cell activation up to T cell exhaustion and promotes regulatory T cell (Tregs) expansion, which further hampers the effector function of CD8 T cells [9,29-31]. Over-expression of CP in AML leads to immune escape through evading detection and elimination by the immune system [32-35].

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) aim to restore antitumor immunity by blocking CP [36–38], leading to the reactivation of T cells [39,40]. While ICI monotherapy (e.g. nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab or durvalumab) has shown success in solid tumors, clinical efficacy in AML remains limited. Initial studies combining ICI with hypomethylating agents suggest potential synergistic effects and acceptable safety profiles [23,29,41–44]. However, immune-related adverse events may occur during ICI treatment [29,45,46], which vary in severity and can potentially affect almost any organ [47,48].

1.5 Aim of this work

This study investigates the role of CP CD273, CD274 and CD279 in AML in the context of DC/DCleu-based immunotherapeutic approaches. Specifically, we analysed CP expression on uncultured blasts from AML pts and healthy donor monocytes, as well as on DC/DCleu generated from leukemic and healthy WB using DC/DCleu-generating Pici-methods (Pici1, Pici2) or Kits (Kit-I, Kit-K, Kit-M). To evaluate the immunomodulatory potential, T cell-enriched immunoreactive cells were stimulated in a mixed lymphocyte culture (MLC) with Kit-pretreated WB and the effect of DC/DCleu stimulation on immune cell composition as well as the induction of antileukemic cytotoxicity was analysed. In addition, CP expression profiles were determined on T cells before and after MLC. Finally, the observed CP expression patterns were correlated with clinical subtypes, response to therapy and the extent of antileukemic activity.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Sample Collection

WB was collected from AML pts (n=38) and from healthy donors (n=15) using lithium-heparin tubes. Samples were provided by the University Hospitals of Augsburg, Munich, Oldenburg and Tuebingen. Informed consent was obtained and the experiments were performed in accordance with the Helsinki protocol and the local ethics committee of Ludwig-Maximilians-University-Hospital Munich.

2.2 Patient characteristics

The median age of AML pts was 59 years (range 21-79) with a male:female ratio of 1.1:1. Healthy donors had a median age of 28 years (range 20-56), male:female ratio 1:1.5. AML was classified according to FAB-classification, subtype, cytogenetic risk and ELN prognostic categories [49]. An overview of the patient characteristics is given in Table 1.

|

Patient No. |

Age |

Sex |

FAB |

Stage |

ELN risk |

Response to induction therapy |

Blast Phenotype (CD) |

IC blasts (%) |

Conducted Experiments |

|

AML |

|||||||||

|

1426 |

61 |

f |

s – M5 |

first dgn |

adverse |

CR |

13, 33, 34, 64, 117 |

40 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1430 |

79 |

m |

p – M5 |

first dgn |

favorable |

NCR |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

70 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1432 |

34 |

m |

p – M5 |

first dgn |

intermediate |

CR |

13, 33, 34, 64 |

80 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1434 |

61 |

f |

s – M? |

first dgn |

adverse |

NCR |

7, 13, 33, 34, 64, 117 |

59 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1439 |

61 |

f |

s – M5 |

first dgn |

favorable |

ND |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

15 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC) |

|

1441 |

60 |

m |

s – M4 |

first dgn |

favorable |

NCR |

13, 33, 64, 65, 117 |

81 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1442 |

73 |

f |

s – M4 |

first dgn |

intermediate |

CR |

33, 117 |

14 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1443 |

64 |

m |

s – M? |

first dgn |

adverse |

NCR |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

28 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC) |

|

1444 |

35 |

f |

p – M1 |

first dgn |

favorable |

CR |

15, 33, 34, 65, 117 |

50 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1447 |

21 |

m |

p – M5 |

first dgn |

intermediate |

CR |

4, 33, 56 |

65 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1449 |

78 |

m |

s – M? |

first dgn |

favorable |

NCR |

15, 64, 65 |

62 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1452 |

44 |

m |

p – M? |

first dgn |

intermediate |

NCR |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

55 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1454 |

60 |

f |

s – M? |

first dgn |

intermediate |

ND |

33, 34, 117 |

33 |

DCC (WB) |

|

1459 |

54 |

m |

p – M4 |

first dgn |

favorable |

CR |

33, 56, 64 |

14 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1460 |

78 |

f |

p – M4 |

first dgn |

intermediate |

CR |

15, 34, 117 |

68 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1462 |

49 |

f |

p – M5 |

first dgn |

favorable |

CR |

13, 33, 34, 56, 64 |

60 |

DCC (WB) |

|

1466 |

47 |

f |

p – M5 |

first dgn |

adverse |

CR |

13, 15, 33, 34, 117 |

15 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1471 |

39 |

m |

p – M1 |

first dgn |

adverse |

NCR |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

69 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1472 |

33 |

f |

p – M2 |

first dgn |

favorable |

CR |

13, 15, 34, 117 |

30 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1473 |

73 |

m |

p – M2 |

first dgn |

adverse |

NCR |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

55 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1480 |

66 |

m |

s – M? |

first dgn |

adverse |

NCR |

13, 33, 117 |

38 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1481 |

62 |

f |

p – M4 |

first dgn |

favorable |

CR |

13, 56, 64, 117 |

29 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1483 |

77 |

m |

p – M5 |

first dgn |

adverse |

ND |

13, 33, 34, 64 |

93 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1489 |

55 |

f |

p – M0 |

first dgn |

favorable |

NCR |

13, 33, 34, 65, 117 |

58 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1492 |

52 |

f |

s – M2 |

first dgn |

nd |

NCR |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

42 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1494 |

55 |

f |

p – M5 |

first dgn |

adverse |

NCR |

13, 34, 117 |

88 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1464 |

72 |

m |

s – M? |

persisting disease |

- |

- |

20, 33, 34, 117 |

44 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1467 |

59 |

f |

s – M? |

persisting disease |

- |

- |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

30 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC) |

|

1468 |

66 |

m |

p – M? |

persisting disease |

- |

- |

33, 34, 56, 117 |

75 |

DCC (WB) |

|

1463 |

60 |

f |

s – M? |

rel |

- |

- |

13, 33, 34, 56 |

30 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1469 |

49 |

m |

p – M4 |

rel |

- |

- |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

94 |

DCC (WB) |

|

1475 |

77 |

m |

s – M? |

rel |

- |

- |

13, 33, 34, 117 |

20 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1486 1424 |

77 37 |

m f |

s – M1 s – M4 |

rel rel after HSCT |

- - |

- - |

33, 34, 56 13, 14, 33, 117 |

45 30 |

DCC (WB) DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

1470 |

67 |

m |

p – M? |

rel after HSCT |

- |

- |

33, 34, 56, 117 |

9 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC, CTX |

|

1474 |

70 |

m |

p – M? |

rel after HSCT |

- |

- |

33, 34, 56, 117 |

80 |

DCC (WB, PBMNC) |

|

1476 |

63 |

f |

s – M? |

rel after HSCT |

- |

- |

13, 33, 34, 65 |

20 |

DCC (WB) |

|

1482 |

75 |

m |

s – M? |

rel after HSCT |

- |

- |

33, 64, 117 |

12 |

DCC (WB), MLC, CTX |

|

Healthy |

|||||||||

|

1421 |

27 |

f |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1425 |

27 |

m |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1428 |

56 |

f |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1429 |

22 |

f |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1431 |

22 |

m |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1436 |

25 |

m |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1438 |

31 |

f |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1440 |

20 |

f |

DCC (WB), MLC |

||||||

|

1446 |

25 |

m |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1448 |

27 |

f |

DCC (WB), MLC |

||||||

|

1458 |

21 |

f |

DCC (WB), MLC |

||||||

|

1478 |

31 |

m |

DCC (WB), MLC |

||||||

|

1479 |

35 |

f |

DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC |

||||||

|

1485 |

21 |

f |

DCC (WB), MLC |

||||||

|

1493 |

25 |

m |

DCC (WB), MLC |

||||||

f female; m male; p primary AML; s secondary AML; M? FAB type not classified; first dgn first diagnosis; rel relapse before or after HSCT (hematopoietic stem cell transplantation); nd no data; CR complete remission; NCR blast persistence; IC blasts immunocytologically determined blasts (Bold letters: blast markers used for quantification of blasts and DCleu); WB whole blood; PBMNC peripheral blood mononuclear cells; DCC dendritic cell culture; MLC mixed lymphocyte culture; CTX cytotoxicity fluorolysis assay.

Table 1: Patients‘ characteristics.

2.3 Cell Culture with whole blood (WB)

2.3.1 Isolation of PBMNCs and CD3+ T cells

PBMNCs were isolated from WB by density gradient centrifugation, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) and used for CD3+ T cell isolation via magnetic bead separation due to MACS-technology (Milteney Biotech, Bergisch Gladbach, Germany), reaching a T cell purity of Ø 84.99% (range 54.24 – 99.56%). Cells were cryopreserved in RPMI-1640-medium (Biochrom) with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma Aldrich Chemie GmbH, Steinheim, Germany) and fetal calf-serum (FCS, Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) at -80°C and thawed as needed [12].

2.3.2 Generation of DC/DCleu from PBMNCs

DC/DCleu were generated from PBMNCs of AML pts or healthy donors using DC/DCleu-generating protocols for ‘Pici1’ and ‘Pici2’ containing specific combinations of response modifiers (further referred to as PBMNCDC(Pici1), PBMNCDC(Pici2)) as given in Table 2 [13]. A culture without added response modifiers served as control (PBMNCDC(Control)). Therefore, 3-4x106 isolated PBMNCs were pipetted in 12-multiwell-plates and diluted with 2ml X-Vivo-15-medium (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland).

DC/DCleu Protocol |

DC/Dcleu Source |

Composition |

Time of addition (day (d)) |

Time of Culture (days) |

Reference |

|

Pici1 |

PBMNC |

GM-CSF 500 U/ml |

d0 |

9-10 |

[13,50] |

|

IL-4 250 U/ml |

d0 |

||||

|

Picibanil 10 µg/ml |

d7 |

||||

|

PGE1 1 µg/ml |

d7 |

||||

|

Pici2 |

PBMNC |

GM-CSF 500 U/ml |

d0 |

||

|

IL-4 250 U/ml |

d0 |

||||

|

Picibanil 10 µg/ml |

d7 |

||||

|

PGE2 1 µg/ml |

d7 |

||||

|

Kit-I |

WB |

GM-CSF 800 U/ml |

d0, d2-3 |

7-8 |

[13,50] European Patent No. 15 801 987.7 - 1118 US Patent 15-517627 MODIBLAST GmBH |

|

Picibanil 10 µg/ml |

|||||

|

Kit-K |

WB |

GM-CSF 800 U/ml |

|||

|

PGE2 1 µg/ml |

|||||

|

Kit-M |

WB |

GM-CSF 800 U/ml |

|||

|

PGE1 1 µg/ml |

Mode of Action:

GM-CSF: Induction of myeloid (DC-) differentiation; IL-4: Induction of DC-differentiation; Picibanil: Danger signaling, DC maturation; PGE1 / PGE2: Danger signaling, DC maturation

Table 2: DC/DCleu-generating protocol.

2.3.3 Generation of DC/DCleu from WB

DC/DCleu were also generated directly from WB using DC/DCleu -generating protocols ‘Kit-I’, ‘Kit-K’ and ‘Kit-M’ [50] given in Table 2. 500µl WB (corresponding to 5.0 – 30.3 x 106 PBMNC) were cultured in 24-multiwell culture plates (ThermoFisher Scientific) and diluted with 500µl X-Vivo-15-medium. A culture without added response modifiers was served as a control (WBDC(Control)).

All cell culture experiments were conducted at standard laboratory conditions comprising 37°C, 21% O2 and 5% CO2.

2.4 Cell-characterization by flow cytometry

Frequencies, subsets and phenotypes of leukemic blasts, T cells, B cells, monocytes and DC/DCleu were quantified by flow cytometric analyses were done as previously described [12]. Therefore cells were stained with monoclonal antibodies (moAbs) labelled with Fluorescein isothiocyanat (FITC), phycoerythrin (PE), tandem Cy7-PE conjugation (Cy7-PE) or allophycocyanin (APC). Dead cells were excluded using 7AADb. Erythrocytes in WB were lysed prior to staining. Staining was performed in PBS containing FCS and the corresponding moAbs for 15 min in the dark.

Cell-Evaluation and quantification was done via fluorescence-activated cell sorting Flow-Cytometer (FACSCaliburTM) and the CellQuestPro-acquisition and analysis software (Becton Dickson, Heidelberg, Germany) with appropriate isotype controls.

Leukemic blasts, DC and DCleu were analysed before and after cell culture using a refined gating strategy. DCleu were defined by co-expression of at least one blast marker (CD15, CD34, CD65, CD117) including lineage-aberrant markers (CD56) and one or two DC markers (CD80, CD206) absent on naïve blasts. DC/DCleu maturation was assessed by CCR7 expression. Subgroup analyses required ≥ 10% DC in the total cell fraction.

2.5 Mixed-lymphocyte-culture (MLC) of T cell-enriched immune-reactive cells with Pici/Kit-treated-cell-suspensions

Autologous T cells were stimulated with DC/DCleu generated from WB (WBDC) generating T cell-enriched immunoreactive cells. Therefore, 1x106 autologous CD3+ T cells (‘effector cells’) were co-cultured with a stimulator cell suspension containing 2.5 x 105 DC/DCleu in 24-mulitwell-tissue-culture plates (ThermoFisher Scientific, Darmstadt, Germany) and diluted in RPMI-1640 medium containing 100 U/ml Penicillin (Biochrom, Berlin, Germany) and 15% human serum. 50 U/ml Interleukin 2 (IL-2, PeproTech, Berlin, Germany) was added on day 0 and day 2-3. Cells were harvested after 6-8 days (further referred to as WBDC-MLC) and used for the cytotoxicity-fluorolysis-assay. T cell subsets were quantified by flow cytometry before and after the MLC [12].

2.6 Cytotoxicity fluorolysis assay

A fluorolysis assay was done to analyse the lytic activity of T cell-enriched immunoreactive cells against leukemic blasts cells [11,50]. Therefore, effector cells (WBDC-MLC) containing 1 x 106 T cells and 1 x 106 thawed PBMNCs (blast containing target cells) were co-cultured in RMPI-1640 medium with 100 U/ml penicillin and 15% human serum for 3 and 24 hours. Controls consisted of effector- and target-cells cultured separately and combined only prior to analysis.

Target cells were pre-stained with blast specific moAbs. After incubation, cells were resuspended in PBS containing 7 AAD and a defined number of Fluorospheres Beads (Beckman coulter, Krefeld, Germany) to quantify viability and cytotoxicity. Data were acquired using flow cytometry with a refined gating strategy [11].

2.7 Statistical Methods

Data is presented as mean ± standard-deviation-values. Statistical comparisons of two groups were performed using the two-tailed t-test in cases with normal distribution or with the Mann-Whitney-Wilcoxon-Test in cases with no normal distribution. Statistical analyses and figures were performed with Microsoft Excel 2010 ® (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) and GraphPad Prism8© (GraphPad Software, California, USA).

Differences were considered as ‘not significant’ in cases with p values > 0.1, as ‘borderline significant’ with p values between 0.1 and 0.05 and as ‘significant’ with p values < 0.05.

3 Results

3.1 Prolog

In the first part of this study, we generated DC/DCleu with the DC/DCleu-generating Kits for Kit-I, Kit-K and Kit-M from leukemic WB or blood from healthy probands as we did in analogy for PBMNC with Pici-generating methods (Pici1, Pici2). We also cultivated WB or PBMNC without addition of any response modifiers as a control. Afterwards we stimulated T cell enriched immunoreactive cells with Pici/Kit treated cells and carried out a cytotoxicity fluorolysis assay (CTX).

In the second part of this study, we analysed the expression of CP on blasts, DC or DCleu before and after DC/DCleu-generation. In addition, we analysed the expression of CP on T cells after MLC. Conclusively, we correlated the CP expression on immunoreactive cells with the anti-leukemic cytotoxic activity, the patients’ age, sex, ELN risk groups and patients’ response to induction chemotherapy. Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

|

Group |

Subgroup |

Surface marker |

Refers to |

Abbreviation |

References |

|

Blast cells |

blasts |

BLA+ e.g. CD34+, CD117+ |

WB or PBMNC |

BLA/WB or /PBMNC |

[13] |

|

DC |

dendritic cells |

DC+ e.g. CD80+, CD206+ |

WB or PBMNC |

DC/WB or /PBMNC |

[13] |

|

leukemia derived DC |

DC+BLA+ |

WB or PBMNC |

DCleu/WB or /PBMNC |

[13] |

|

|

mature DC |

DC+CCR7+ |

WB or PBMNC |

DCmat/WB or /PBMNC |

[50] |

|

|

Monocytes |

CD14+ monocytes |

CD14+ |

WB or PBMNC |

mo14+/WB |

[50] |

|

T cells |

CD3+ T cells |

CD3+ |

WB or PBMNC |

T/WB or /PBMNC |

[11] |

|

non-naive T cells |

CD3+CD45RO+ |

CD3 |

Tnon-naive/ T |

[11] |

|

|

CP expressing cells |

CD279+ expressing blasts |

Bla+CD279+ |

Bla |

Bla279+/Bla |

[51] |

|

CD279+ expressing monocytes |

CD14+ CD279+ |

CD14 |

mo14+279+/mo14+ |

[52] |

|

|

CD279+ expressing DCleu |

DC+Bla+CD279+ |

Bla |

DCleu279+/Bla |

||

|

CD279+ expressing T cells |

CD3+CD279+ |

CD3 |

T279+/ T |

[53] |

|

|

CD274+ expressing blasts |

Bla+CD274+ |

Bla |

Bla274+/Bla |

[51] |

|

|

CD274+ expressing monocytes |

CD14+ CD274+ |

CD14 |

mo14+274+/mo14+ |

[54] |

|

|

CD274+ expressing DCleu |

DC+Bla+CD274+ |

Bla |

DCleu274+/Bla |

||

|

CD274+ expressing T cells |

CD3+CD274+ |

CD3 |

T274+/ T |

[53,55] |

|

|

CD273+ expressing blasts |

Bla+CD273+ |

Bla |

Bla273+/Bla |

[51] |

|

|

CD273+ expressing monocytes |

CD14+ CD273+ |

CD14 |

mo14+273+/mo14+ |

[54] |

|

|

CD273+ expressing DCleu |

DC+Bla+CD273+ |

Bla |

DCleu273+/Bla |

||

|

CD273+ expressing T cells |

CD3+CD273+ |

CD3 |

T273+/T |

[53] |

Table 3: Cells and cell subsets as evaluated by flow cytometry.

3.2 Expression of CP on uncultured AML patients’ blasts or T cells or on healthy donors’ monocytes or T cells

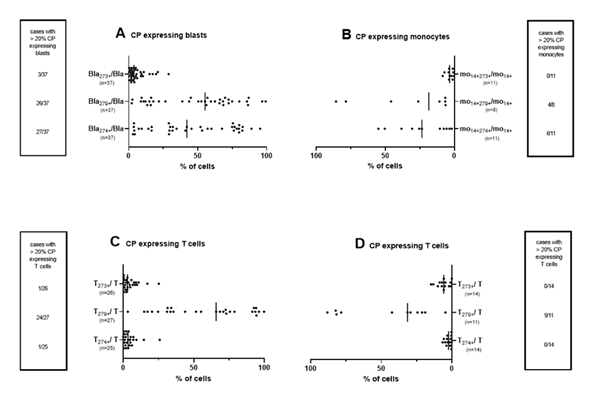

We determined the expression of several CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) on leukemic blasts in uncultured WB of AML pts as well as frequencies of CP expressing monocytes in uncultured healthy WB. In addition, we quantified CP expressing T cells in leukemic WB and in WB of healthy probands (Figure 1).

Given are median frequencies of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing uncultured leukemic blasts from AML pts (A) or monocytes from healthy probands (B) as well as T cells from pts with AML (C) or from healthy probands (D) in uncultured WB coexpressing CP markers. Each dot plot represents one individual sample. Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

3.2.1 CP expressing blasts and healthy monocytes

We quantified CD274, CD279 and CD273 expressing leukemic blasts in uncultured WB: We found low frequencies of CD273+ leukemic blasts (most times < 10% CD273+ blasts). In only 3 out of 37 cases we found more than 20% CD273 expressing blasts. We found higher frequencies of CD279 expressing leukemic blasts (on approximately 50% of blasts). In 25 of 37 cases, we observed more than 20% CD279-expressing blasts. We found also high frequencies of CD274 expressing blasts in uncultured WB (Figure 1A).

We found low frequencies of CP (CD273, CD279 and CD274) expressing uncultured monocytes in healthy samples (Figure 1B).

3.2.2 CP expressing uncultured T cells from AML patients and healthy probands

We found low frequencies of CD273 and CD274 expressing uncultured T cells in leukemic WB as well as in WB of healthy probands. In only 1 out of 24 cases we noticed more than 20% CD273 respectively CD274 expressing T cells in AML patients’ WB. In contrast, higher frequencies of CD279 expressing T cells were found in healthy (Ø 45%) as well as in AML patients’ samples (Ø 58%) (Figure 1C, Figure 1D).

3.3 DC/DCleu generation from healthy and leukemic PBMNC

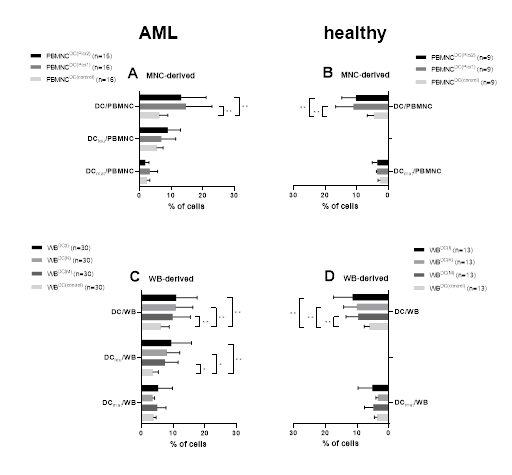

Significantly higher frequencies of DC were generated with Pici1 and Pici2 compared to control from leukemic as well as from healthy PBMNC. We could generate DC or DCleu in PBMNC from healthy and leukemic samples with both Pici1 and Pici2 vs. untreated control cultures, thereby confirming data shown before [13] (Figure 2A, B).

3.4 DC/DCleu generation from healthy and leukemic WB

We evaluated the effect of the several Kits on the generation of DC/DCleu for leukemic as well as healthy WB.

WB samples from AML patients (C) and healthy probands (D) were cultured with or without Kits for 7 days. In parallel PBMNC samples from AML patients (A) and healthy volunteers (B) were cultured with or without Picis for 9 days. Given are mean frequencies ± standard deviation of generated DC- and DC subgroups in WB/PBMNC. Statistical analyses were conducted using multiple t-test: Differences were considered as highly significant with p values <0.005 (**) and as significant with p values <0.05 (*). Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

Significantly higher frequencies of DC were generated with Kit-I, Kit-K and Kit-M compared to control from leukemic as well as from healthy WB. We observed significantly higher frequencies of DCleu with Kit-I, Kit-K and Kit-M compared to Kit-Control for leukemic WB. In summary, we were able to generate significantly higher frequencies of DC and DCleu with immunomodulatory Kits from healthy and leukemic WB as compared to controls thereby confirming data shown before [13,50] (Figure 2C, D). The proliferation of blasts was not induced under Kit treatment (data not shown).

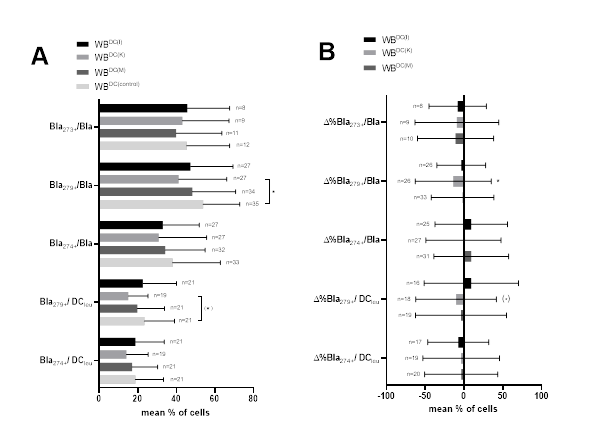

3.5 Expression of CP on AML patients’ blasts and DCleu after DC/DCleu-culture

We evaluated CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing blasts and DCleu of AML patients’ WB after DC/DCleu-generation with ‘Kits’ (WBDC(I), WBDC(K), WBDC(M)) compared to control (WBDC(control)) (Figure 3A). In addition, we give the relative changes of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing leukemic blasts and DCleu as percentual differences (‘delta’ (Δ%)) for Kit-I, Kit-K and Kit-M compared to control (Figure 3B). Overall, we found lower frequencies of CP expressing blasts after DC/DCleu-culture for all three Kits and significantly lower frequencies of CD279 expressing blasts for WBDC(K) compared to control.

Given are mean frequencies ± standard deviation of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing leukemic blasts and DCleu after DC/DCleu-generation from leukemic WB for Kit-I, Kit-K, Kit-M compared to control (A). Given are the relative changes of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing leukemic blasts and DCleu as percentual differences (‘delta’ (Δ%)) for Kit-I, Kit-K and Kit-M compared to control (B). Statistical analyses were conducted using multiple t-test: Differences were considered as significant with p values <0.05 (*) and as borderline significant ((*)) with p values 0.10 to 0.05. Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

Lower frequencies of CP (CD279 and CD274) expressing DCleu were seen after the influence of Kit-I, Kit-K and Kit-M. Borderline significantly lower frequencies of Bla279+/DCleu were found for Kit-K compared to control.

Relative changes of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing leukemic blasts and DCleu compared to control are given in Figure 3B. Overall, we show in almost all cases a decrease in CP expression on blasts as well as on DCleu compared to control.

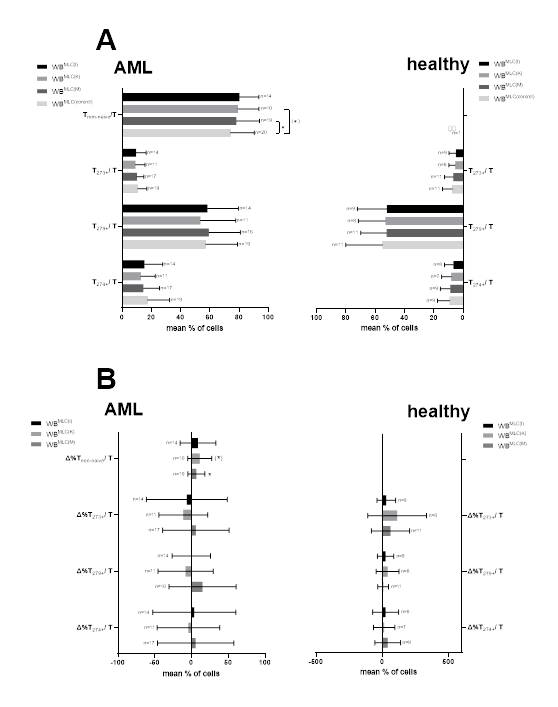

3.6. Stimulatory impact of Kit pre-treated WB on T cells in MLC

To evaluate the potential stimulating effect of generated DC/DCleu on the composition of immunoreactive cells, T cell compositions were evaluated before (uncultured MLC) and after stimulation with Kits-treated WB (WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K), WBMLC(M) WBMLC(control)). Significantly higher frequencies of Tnon-naive cells after Kit-M treatment could be found in comparison to control. We could also find borderline significantly increased Tnon-naive cells in Kit-K pre-treated samples (Figure 4A).

3.7 Expression of CP on AML patients’ T cells after stimulation in MLC with Kit pre-treated WB

Frequencies of CP expressing T cells were analysed after stimulation in MLC with Kit pre-treated WB of AML patients and also of healthy probands (Figure 4A). We quantified frequencies of CP (CD274, CD279, CD273) expressing T cells in AML patients’ WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K), WBMLC(M) compared to WBMLC(control). We observed comparable frequencies of T273+/T and T274+/T in WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K) and WBMLC(M) compared to WBMLC(control) for leukemic and healthy WB. We could detect lower frequencies for T279+/T in Kit pre-treated WB of healthy probands compared to WBMLC(control). Although we observed slightly lower frequencies of CP expressing T cells in Kit pre-treated WB compared to WBMLC(control) of AML patients as well as healthy probands, results did not differ significantly (Figure 4A).

In addition, we compared the relative changes of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing T cells (Figure 4B). Results are given as percentual differences (Δ%) of CP expressing T cells in WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K), WBMLC(M) in proportion to WBMLC(control). We could not find any significant differences between the individual values.

Given are mean frequencies ± standard deviation of activated non-naive T cells and CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing leukemic or healthy T cells after stimulation in MLC with Kit pre-treated WB (WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K), WBMLC(M)) compared to untreated WB (WBMLC(control)) (A). Given are the relative changes of non-naive T cells and CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing T cells as percentual differences (‘delta’ (Δ%)) for Kit-I, Kit-K and Kit-M compared to control (B). Statistical analyses were conducted using multiple t-test: Differences were considered as significant with p values <0.05 (*) and as borderline significant ((*)) with p values 0.10 to 0.05. Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

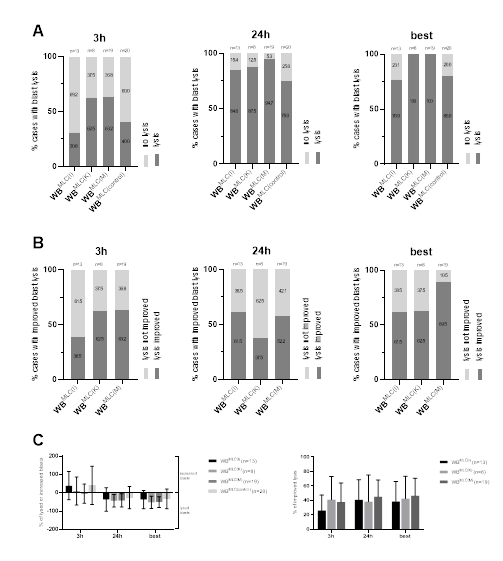

3.8 Anti-Leukemic Cytotoxicity

Given are the proportions of cases with blast lysis (A) and the mean ± range of lysed or increased blasts in WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K), WBMLC(M) and WBMLC(control) after 3 h, 24 h and the “best” achieved blast lysis after 3 h or 24 h (C); the proportions of cases with an improved blast lysis (B) in WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K) and WBMLC(M) in relation to WBMLC(control) after 3 h, 24 h and the “best” achieved improved blast lysis after 3 h or 24 h. Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

To evaluate the anti-leukemic cytotoxicity of DC/DCleu-stimulated immunoreactive cells, we analysed the lytic activity of WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K), WBMLC(M) and WBMLC(control) through CTX after 3 h and after 24 h of incubation of effector and leukemic target cells. After 3 h we could see a lysis of target cells in WBMLC(I) in about 30.8% of cases, whereas we could observe a lysis of target cells in WBMLC(K) and WBMLC(M) in more than 60% of cases. In the control group we observed a blast lysis in 40% of cases. After 24 h, more cases of WBMLC(I), WBMLC(K), WBMLC(M) and WBMLC(control) attained lysis, in which WBMLC(M) showed the highest percentage of cases with lysis (94.7%) compared to WBMLC(control) (75% of cases) (Figure 5A). Selecting the best achieved result after 3h or 24h, we discovered blast lysis in 100% of cases for WBMLC(K) and WBMLC(M). WBMLC(I) and WBMLC(control) achieved lysis in about approximately 80% of cases (Figure 5A). Improved lysis, defined as the relative improvement of blast lysis of Kit treated vs. not pre-treated cases (WBMLC(control)), was observed after 3h in 38.5% of cases for WBMLC(I) and in more than 60% of cases for WBMLC(K) and WBMLC(M). After 24h more than 50% of cases for WBMLC(I) and WBMLC(M) showed an improved lysis. Selecting the best achieved result after 3h or 24h, we found improved blast lysis in almost 90% of cases for WBMLC(M). WBMLC(I) and WBMLC(K) showed improved lysis in more than 60% of cases (Figure 5B).

We observed highest frequencies of lysed blasts especially for Kit-K and Kit-M after 24h leading to best improved lysis compared to the control thereby confirming data shown before (Figure 5C) [13,50].

3.9 Correlation analyses

3.9.1 Correlation of frequencies of CP expressing uncultured cells with patients’ clinical data

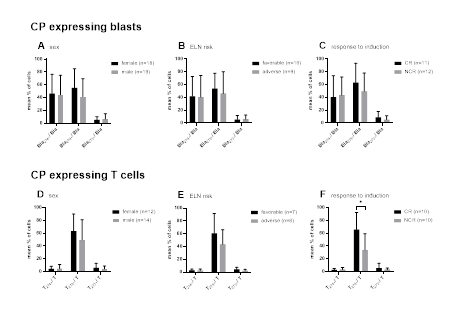

We correlated frequencies of CP expressing uncultured blasts or T cells in samples from AML patients with patients’ clinical data. We did not find correlations between frequencies of uncultured CP expressing blasts or T cells with patients’ sex, ELN risk or response vs. no response to induction chemotherapy, although frequencies of T279+/T were (significantly) higher in cases with favourable ELN risk as well as in responders to induction chemotherapy (Figure 6).

Given are mean frequencies ± standard deviation of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing uncultured leukemic blasts and T cells from AML pts subdivided into sex (female vs. male) (A, D), ELN risk groups (favorable vs. adverse) (B, E) and patients’ response to induction chemotherapy (complete remission vs. blast persistence) (C, F). Differences were considered as significant with p values <0.05 (*). Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

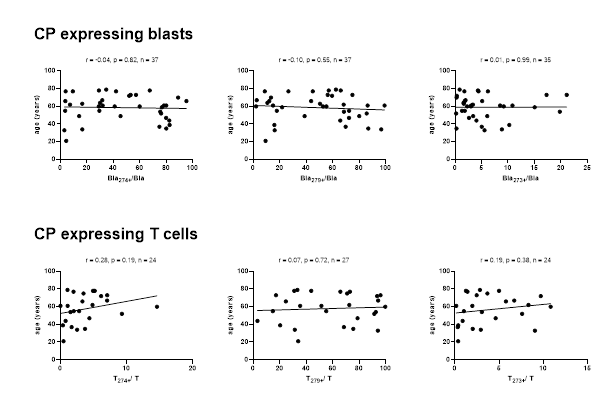

Correlation of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing uncultured leukemic blasts and T cells from AML pts with the patients’ age. Correlation coefficients (r) and p-values (one-tailed) are given, evaluated by Pearson correlation analyses. Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

No significant correlations were found between frequencies of CP expressing uncultured blasts and T cells with patients’ age (Figure 7).

3.9.2 Correlation of frequencies of CP expressing uncultured blasts or T cells with improved blast lysis after MLC with Kit pre-treated WB

We correlated frequencies of CP expressing blats and T cells in uncultured WB samples from AML patients with achieved improved blast lysis after Kit pre-treated vs. not pre-treated MLC. We found no correlations between frequencies of CP expressing blasts or T cells and achieved improved blast lysis with Kit-I or Kit-M pre-treated WB after MLC. Kit-K results could not be correlated due to low case numbers (Figure 8).

Correlation of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing uncultured leukemic blasts and T cells from AML pts with the relative improvement of blast lysis (= improved blast lysis) in Kit-I and Kit-M treated WB after MLC. Correlation coefficients (r) and p-values (one-tailed) are given, evaluated by Pearson correlation analyses. Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

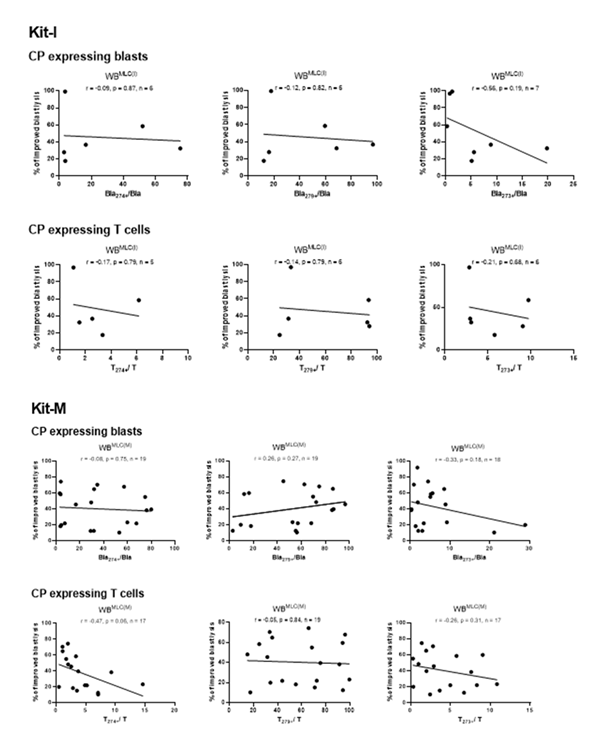

3.9.3 Correlation of frequencies of CP expressing blasts or T cells after DC/DCleu -generation with improved blast lysis after MLC with Kit pre-treated WB

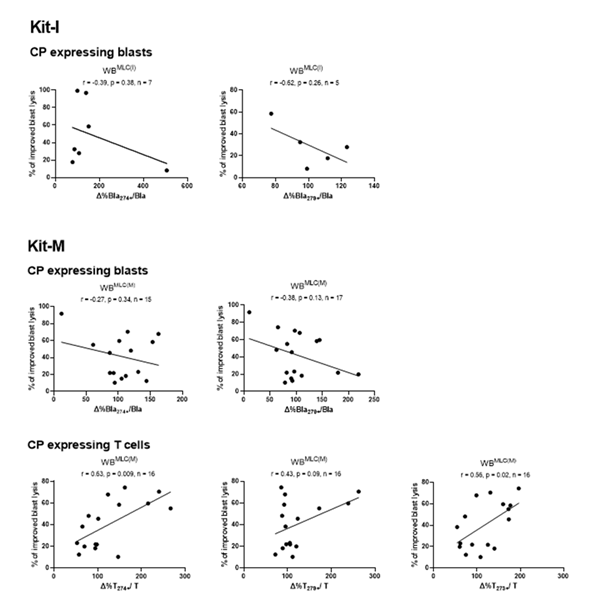

We observed (non-significant) negative correlations between improved blast lysis and relatively changed frequencies of CP expressing blasts after MLC with Kit-I or Kit-M pre-treated WB vs. control (Figure 9). Noteworthy, we found significant positive correlations between frequencies of CP expressing T cells after MLC and improved blast lysis via CTX for Kit-M pre-treated samples (Figure 9). An examination of T cells after MLC for Kit-I and Kit-K was not possible due to low case numbers.

Correlation of relative changed frequencies of CP (CD274, CD279 and CD273) expressing leukemic blasts and T cells from AML pts with the relative improvement of blast lysis (= improved blast lysis) in Kit-I and Kit-M treated WB after MLC. Correlation coefficients (r) and p-values (one-tailed) are given, evaluated by Pearson correlation analyses. Abbreviations of all cell types are given in Table 3.

4 Discussion

4.1 Immunotherapy of AML

Recent immunotherapeutic strategies for AML target leukemic blasts either through passive approaches, such as antibody- or cell-based therapies, or through immune (re)activating approaches including vaccines or immune checkpoint blockade [56].

DCleu-based immunotherapies mediate leukemia-specific immune responses using individual patients’ ex vivo generated or in vivo produced DC/DCleu (e.g. [12,57,58]). We confirm, that DC/DCleu generation from leukemic PBMNC or WB is successful using Pici-methods (Pici1, Pici2) or blastmodulatory Kits (Kit-I, Kit-K, Kit-M) [12,13,18]. No statistically significant differences were detected between the individual Kits or Pici protocols. However, a trend favoring Kit-M was observed, showing slightly higher efficiency in DC/DCleu generation compared to Kit-I and Kit-K (Figure 1).

4.2 DC/DCleu generation and Antileukemic cytotoxicity

We could also confirm, that Pici or Kit pre-treated PBMNC or WB leads to improved T/immune cell activation (Figure 4A), resulting in (improved) blast lysis, as shown by CTX assay after MLC [13,50,57] (Figure 5). These cytotoxic effects appear to involve distinct mechanisms: a rapid perforin/granzyme-mediated pathway, likely responsible for blast lysis after 3 hours of incubation, and a delayed Fas/FasL-dependent pathway becoming effective after 24 hours [11,12]. Ongoing studies aim to determine whether DC/DCleu generation out of leukemic blasts can be achieved using Kits in vivo [58].

4.3 CP expressing blasts or monocytes and T cells in AML

The expression of CD274, CD279 and CD273 was analysed on uncultured leukemic blasts and on monocytes from healthy probands. In addition, we quantified CP expressing T cells in leukemic WB and in WB of healthy probands (Figure 1).

CP are known for their immunoregulatory properties. We found higher frequencies of CP expressing blasts for all three CP markers (CD274, CD279 and CD273) compared to frequencies of CP expressing monocytes of healthy probands (Figure 1). It is known, that CD279 expression is higher on blast and T cells in newly diagnosed and relapsed AML patients compared to healthy controls [35,56,59-61]. Frequencies of CD279 expressing monocytes seems to be significantly higher in renal cell carcinoma patients comparing to healthy probands [52]. Royer et al. [54] showed varying and modified expression rates of CD279 expressing monocytes under stress condition (e.g. in vitro stimulation, hip fracture or sepsis) although CP expression between young and old patients did not differ in the basal state. Previous studies showed high frequencies of CD279 expressing monocytes in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma, but did not show CD279 expression in monocyte subsets of healthy probands [62].

Expression of CD279 on T cells was shown to increase with disease progression [56]. Confirming data shown before, we found higher frequencies of CD279 expressing T cells in AML patients’ samples compared to healthy controls (Figure 1), thereby confirming data shown before [56,63,64]. Previous studies also showed variable, but approximately 60% CD279 coexpressing healthy memory CD8 T cells [65]. In patients with lung cancer low frequencies of naïve T cells show low (~1%) whereas high frequencies of central memory and effector memory T cells (40–60%) coexpressing CD279 were found [66-68]. With aging, expression of CD279 is increased on CD8 T cells as well as on CD4 T cells [69].

CD274 is expressed by hematopoietic cells such as DC or monocytes and non-hematopoietic cells [20,70]. The expression of CD274 changes over time during an AML disease: it is only minimally expressed by leukemic cells at the time of initial diagnosis but significantly upregulated as the disease progresses [71]. The varying expression rates over time on blasts could be explained by varying frequencies of CD274 expressing uncultured blasts. We found rather low frequencies of CD274 expressing monocytes in healthy probands, thereby confirming previous results [72,73] (Figure 1).

We found low expression levels of CD273 on leukemic blasts or monocytes as well as T cells from healthy or leukemic blood donors (Figure 1), thereby confirming previous data, showing low expression on DC, macrophages or activated T cells [74].

The rather low frequencies of CP expressing monocytes, found by us, could be explained by differential expression of CP within monocyte subtypes [54]. The functionality of CP within monocytes is currently still poorly understood.

An interesting approach could be to reactivate patients’ immune system against blasts by modulating CP expression or functionality. To investigate the influence of Kit-treatment on CP expression, we compared frequencies of CP expressing blasts after DC/DCleu-generation as well as T cells’ CP expression after MLC. Overall, we found (significantly) lower expression levels of CD274, CD279 and CD273 on blasts after Kit-treatment compared to control (Figure 3).

We confirm with our data, that Pici or Kit pre-treated AML (MNC or WB) samples lead to increased frequencies of mature/leukemic derived DC vs. control and moreover to increased frequencies of activated T cells leading to improved blasts lysis vs. control (Figure 2, Figure 4, Figure 5) [12,13].

We found comparable frequencies of CP expressing T cells from AML patients’ after MLC with Kit pre-treated compared to untreated WB (Figure 4), demonstrating that Kits pre-treatment of leukemic WB does not increase frequencies of CP expressing T cells after MLC compared to control. This could also mean, that CP expression on T cells is not centrally involved in (Kit mediated) antileukemic reactions.

Current studies have indicated the potential clinical benefits of ICI against solid tumors as well as AML [38]. Also a combination with intensive chemotherapy, hypomethylating agents or other targeted therapies is possible and lead to improved outcome compared to monotherapy with ICI [35,36]. Moreover, several new co-inhibitory pathways are currently studied for their potential impacts on improving anti-tumor immune responses [34].

4.4 Correlations

We confirm data, that Kit pre-treatment of leukemic blood increases blast lysis after MLC (Figure 5). That is why we correlated frequencies of CP expressing T cells/blasts before and after DC or MLC-culture with several clinical and functional parameters. Although some studies showed that high frequencies of CD279 as well as CD274 expressing blasts in AML patients are associated with a poor prognosis [23,64,75], we did not observe significantly different frequencies of CD279 or of CD274 expressing blasts for AML patients concerning to their ELN risk group (Figure 6), thereby conforming data of Zajac et al. [75], who did not identify significant differences in overall survival between groups with high or low CD274 expression [75].

In contrast to data from Zajac et al. [75], we did not show positive correlations between age and CP expression [75]. We can add in addition, that frequencies of CP expressing leukemic blasts or T cells were independent of patients’ age, sex or ELN risk group (Figure 6, 7). In contrast to data published before [76], we did not find a correlation between frequencies of CP expressing blasts with patients’ response to induction therapy, but in contrast lower frequencies of T279+/T in AML patients with no response to induction chemotherapy (Figure 6).

Whereas we did not find significant correlations between frequencies of uncultured blasts or T cells coexpressing CP with later on achieved improved blasts lysis (mediated by Kit pre-treated WB) (Figure 8), we found a negative correlation of CP expressing blasts in Kit treated samples (in relative to control) with improved blasts lysis and in Kit-M pre-treated samples (in relative to control) with improved blast lysis (Figure 9). These findings could be explained by the inhibitory effects of CP expressing blasts leading to a decreased T cell activation [74,77]. Especially CD279 is a known as a T cell inhibitor [78,79]. Inhibition of immune cells like DCleu through CD279 significantly impairs antigen presentation required to stimulate adaptive immune responses [52]. Previous results suggest that both CD279 and CD274 DC are capable to inhibit T cell response by regulating effector functions of T cells and antitumor immunity [80]. Tumor growth can be effectively suppressed following the transfer of CD279-deficient DC [80].

Surprisingly, there was a significant positive correlation found between improved blast lysis and the frequencies of CP expressing T cells after MLC for Kit-M (Figure 9). These data point to a gained immune activating antileukemic role of CP expressing T cells achieved after the influence of Kit-M, as CD279-expressing DC modulate T cell responses directly in the tumor microenvironment [80]. The enhancement of antileukemic activity, particularly observed ex vivo with Kit-M, could also occur via a CP-independent mechanism.

4.5 Future directions

Our results show increased frequencies of CP expressing blasts and T cells in the blood of AML patients. Kit pre-treatment of patient WB, particularly with Kit-M, followed by MLC, resulted in enhanced blast lysis without increasing the frequency of CP expressing blasts, DC and T cells. High, relatively (compared to control) decreased frequencies of blasts coexpressing CP markers and high relatively (compared to control) increased frequencies of CP expressing T cells correlated with improved blast lysis. These data has to be interpreted as a change of functionality of CP expressing cells under the influence of Kit-M - independent of patients’ sex, age or clinical/haematological data and more or less from frequencies of CP expressing blast or T cells.

Targeted modulation of immune escape mechanisms, particularly through the regulation of CP expression on blasts and effector cells, could improve antileukemic immunity – an approach that has been insufficiently investigated so far, especially in the context of DCleu-based strategies. Therefore the combination of ICI with DC/DCleu-based immunotherapies could represent a promising strategy for improving T-cell activation and restoring immune regulation in AML. However, this needs to be confirmed by further studies. Ongoing research and additional studies will be essential to clarify the efficacy, safety and optimal use of DC-based immunotherapies, ICI and their potential combination in AML and thus improve clinical outcomes for AML patients.

Author Contributions: C.A. conducted DCC (WB, PBMNC), MLC and CTX experiments and all flow cytometric and statistical analyses. M.W., D.C.A., C.S. (Christoph Schwepcke), F.D.-G. performed additional DCC, MLC, CTX, and CSA experiments, which were analysed by C.A. D.M.K., A.R., C.S. (Christoph Schmid) provided leukemic whole blood samples and corresponding diagnostic reports. H.M.S. designed the study. C.A. and H.M.S. drafted the manuscript.

Statement of Ethics: Sample collection was conducted after obtaining written informed consent of the blood donor and in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and the ethic committee of the Ludwig-Maximilians-University Hospital Munich (vote No. 33905).

Acknowledgments: The authors thank patients, nurses, and physicians on the wards for their support and the diagnostic laboratories as well as the treating institutions for the patients’ diagnostic reports.

Conflicts of Interest: H.M.S. is involved with Modiblast Pharma GmbH (Oberhaching, Germany), which holds the European Patent 15 801 987.7-1118 and US Patent 15-517627, ‘Use of immunomodulatory effective compositions for the immunotherapeutic treatment of patients suffering from myeloid leukemias’. For all other authors, there are no conflicts of interest to declare.

References

- Löwenberg B, Downing JR, Burnett A, et al. Acute myeloid leukemia. The New England Journal of Medicine 341 (1999): 1051-1062.

- Döhner H, Wei AH, Appelbaum FR, et al. Diagnosis and management of AML in adults. 2022 recommendations from an international expert panel on behalf of the ELN. Blood 140 (2022): 1345-1377.

- Metzeler KH, Herold T, Rothenberg-Thurley M, et al. Spectrum and prognostic relevance of driver gene mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. Blood 128 (2016): 686-698.

- Smith M, Barnett M, Bassan R, et al. Adult acute myeloid leukaemia. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 50 (2004): 197-222.

- Ionescu F, David JC, Ravichandran A, et al. Hypomethylating Agents and Venetoclax for Acute Myeloid Leukemia Relapsed After Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma & Leukemia 24 (2024): 400-406.

- DiNardo CD, Maiti A, Rausch CR, et al. Ten-day Decitabine with Venetoclax in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Single-arm Phase 2 Trial. The Lancet. Haematology 7 (2020): e724-36.

- Zeidan AM, Wang R, Wang X, et al. Clinical outcomes of older patients with AML receiving hypomethylating agents: a large population-based study in the United States. Blood Advances 4 (2020): 2192-2201.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts. National Cancer Institute. Cancer Stat Facts.

- Tettamanti S, Pievani A, Biondi A, et al. Catch me if you can: how AML and its niche escape immunotherapy. Leukemia 36 (2022): 13-22.

- Ansprenger C, Amberger DC, Schmetzer HM, et al. Potential of immunotherapies in the mediation of antileukemic responses for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS) - With a focus on Dendritic cells of leukemic origin (DCleu). Clinical Immunology (Orlando, Fla.) 217 (2020): 108-467.

- Klauer LK, Schutti O, Ugur S, et al. Interferon Gamma Secretion of Adaptive and Innate Immune Cells as a Parameter to Describe Leukaemia-Derived Dendritic-Cell-Mediated Immune Responses in Acute Myeloid Leukaemia in vitro. Transfusion Medicine and Hemotherapy 49 (2021): 44-61.

- Schutti O, Klauer L, Baudrexler T, et al. Effective and Successful Quantification of Leukemia-Specific Immune Cells in AML Patients’ Blood or Culture, Focusing on Intracellular Cytokine and Degranulation Assays. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25 (2024).

- Amberger DC, Doraneh-Gard F, Gunsilius C, et al. PGE1-Containing Protocols Generate Mature (Leukemia-Derived) Dendritic Cells Directly from Leukemic Whole Blood. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 20 (2019).

- Kremser A, Dressig J, Grabrucker C, et al. Dendritic cells (DCs) can be successfully generated from leukemic blasts in individual patients with AML or MDS: an evaluation of different methods. Journal of Immunotherapy (Hagerstown, Md: 1997) 33 (2010): 185-199.

- Plett C, Klauer LK, Amberger DC, et al. Immunomodulatory kits generating leukaemia derived dendritic cells do not induce blast proliferation ex vivo: IPO-38 as a novel marker to quantify proliferating blasts in acute myeloid leukaemia. Clinical Immunology (Orlando, Fla.) 242, (2022): 109083.

- Atzler M, Baudrexler T, Amberger DC. In Vivo Induction of Leukemia-Specific Adaptive and Innate Immune Cells by Treatment of AML-Diseased Rats and Therapy-Refractory AML Patients with Blast Modulating Response Modifiers. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 25 (2024).

- Filippini Velázquez G, Anand P, Abdulmajid J. Clinical stabilization of a highly refractory acute myeloid leukaemia under individualized treatment with immune response modifying drugs by in vivo generation of dendritic cells of leukaemic origin (DCleu) and modulation of effector cells and immune escape mechanisms. Biomarker Research 13 (2025): 104.

- Unterfrauner M, Rejeski HA, Hartz A, et al. Granulocyte-Macrophage-Colony-Stimulating-Factor Combined with Prostaglandin E1 Create Dendritic Cells of Leukemic Origin from AML Patients’ Whole Blood and Whole Bone Marrow That Mediate Antileukemic Processes after Mixed Lymphocyte Culture. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 24 (2023).

- Ramamurthy C, Godwin JL, Borghaei H, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy: What Line of Therapy and How to Choose?. Current Treatment Options in Oncology 18 (2017): 33.

- Keir ME, Butte MJ, Freeman GJ, et al. PD-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annual Review of Immunology 26 (2008): 677-704.

- Sivori S, Vacca P, Del Zotto G, et al. Human NK cells: surface receptors, inhibitory checkpoints, and translational applications. Cellular & Molecular Immunology 16 (2019): 430-441.

- Anton-Pampols P, Martinez Valenzuela L, Fernandez Lorente L, et al. Immune checkpoint molecules performance in ANCA vasculitis. RMD Open 10 (2024).

- Giannopoulos K. Targeting Immune Signaling Checkpoints in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Journal of Clinical Medicine 8 (2019).

- Kamphorst HAO, Wieland A, Nasti T, et al. Rescue of exhausted CD8 T cells by PD-1 targeted therapies is CD28-dependent. Science (New York, N.Y.) 355 (2017): 1423-1427.

- Zhang L, Gajewski TF, Kline J, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 interactions inhibit antitumor immune responses in a murine acute myeloid leukemia model. Blood 114 (2009): 545-1552.

- Liu Y, Gao Y, Hao H, et al. CD279 mediates the homeostasis and survival of regulatory T cells by enhancing T cell and macrophage interactions. FEBS Open Bio 10 (2020): 1162-1170.

- Khan M, Zhao Z, Arooj S, et al. Soluble PD-1: Predictive, Prognostic, and Therapeutic Value for Cancer Immunotherapy. Frontiers in Immunology 11 (2020).

- Baumeister SH, Freeman GJ, Dranoff G, et al. Coinhibitory Pathways in Immunotherapy for Cancer. Annual review of immunology 34 (2016): 539-573.

- Solomon SR, Solh M, Morris LE, et al. Phase 2 study of PD-1 blockade following autologous transplantation for patients with AML ineligible for allogeneic transplant. Blood Advances 7 (2023): 5215-5224.

- Parry RV, Chemnitz JM, Frauwirth KA, et al. CTLA-4 and PD-1 Receptors Inhibit T-Cell Activation by Distinct Mechanisms†. Molecular and Cellular Biology 25 (2005): 9543-9553.

- Ciotti G, Marconi G, Sperotto A, et al. Biological therapy in elderly patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 23 (2023): 175-194.

- Ribas A, Wolchok JD. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science (New York, N.Y.) 359 (2018): 1350-1355.

- Toffalori C, Zito L, Gambacorta V, et al. Immune signature drives leukemia escape and relapse after hematopoietic cell transplantation. Nature Medicine 25 (2019): 603-611.

- Taghiloo S, Asgarian-Omran H. Immune evasion mechanisms in acute myeloid leukemia: A focus on immune checkpoint pathways. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology 157 (2021): 103164.

- Isidori A, Cerchione C, Daver N, et al. Immunotherapy in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Where We Stand. Frontiers in Oncology 11 (2021).

- Gómez-Llobell M, Peleteiro Raíndo A, Climent Medina J, et al. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Meta-Analysis. Frontiers in Oncology 12 (2022): 882531.

- Armand P. Immune checkpoint blockade in hematologic malignancies. Blood 125 (2015): 3393-3400.

- Tabata R, Chi S, Yuda J, et al. Emerging Immunotherapy for Acute Myeloid Leukemia, International Journal of Molecular Sciences 22 (2021).

- Rizvi NA, Hellmann MD, Snyder A, et al. Cancer immunology. Mutational landscape determines sensitivity to PD-1 blockade in non-small cell lung cancer. Science (New York, N.Y.) 348 (2015): 124-128.

- Han Y, Liu D, Li L, et al. PD-1/PD-L1 pathway: current researches in cancer. American Journal of Cancer Research 10 (2020): 727-742.

- Zeidner JF, Vincent BG, Ivanova A, et al. Phase II Trial of Pembrolizumab after High-Dose Cytarabine in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Blood Cancer Discovery 2 (2021): 616-629.

- Abbas HA, Alaniz Z, Mackay S, et al. Single-cell polyfunctional proteomics of CD4 cells from patients with AML predicts responses to anti–PD-1–based therapy. Blood Advances 5 (2021): 4569-4574.

- Daver N, Garcia-Manero G, Basu S, et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Biomarkers of Response to Azacitidine and Nivolumab in Relapsed/Refractory Acute Myeloid Leukemia: A Non-randomized, Open-label, Phase 2 Study. Cancer Discovery 9 (2018) 370-383.

- Stahl M, Goldberg AD. Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia: Novel Combinations and Therapeutic Targets, Current oncology reports 21 (2019): 37.

- Bewersdorf JP, Shallis RM, Sharon E, et al. A multicenter phase Ib trial of the histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat in combination with pembrolizumab in patients with myelodysplastic syndromes/neoplasms or acute myeloid leukemia refractory to hypomethylating agents. Annals of Hematology 103 (2024): 105-116.

- Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nature Reviews Cancer (2012).

- Bair SM, Strelec LE, Feldman TA, et al. Outcomes and Toxicities of Programmed Death-1 (PD-1) Inhibitors in Hodgkin Lymphoma Patients in the United States: A Real-World, Multicenter Retrospective Analysis. The oncologist 24 (2019): 955-962.

- Arnab G. Checkpoint inhibitors in AML: are we there yet? (2019).

- Bataller A, Garrido A, Guijarro F, et al. European LeukemiaNet 2017 risk stratification for acute myeloid leukemia: validation in a risk-adapted protocol. Blood Advances 6 (2022): 1193-1206.

- Schwepcke C, Klauer LK, Deen D, et al. Generation of Leukaemia-Derived Dendritic Cells (DCleu) to Improve Anti-Leukaemic Activity in AML: Selection of the Most Efficient Response Modifier Combinations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23 (2022).

- Sehgal A, Whiteside TL, Boyiadzis M, et al. PD-1 Checkpoint Blockade in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Expert Opinion on Biological Therapy 15 (2015): 1191-1203.

- MacFarlane AW, Jillab M, Plimack ER, et al. Campbell, PD-1 expression on peripheral blood cells increases with stage in renal cell carcinoma patients and is rapidly reduced after surgical tumor resection. Cancer Immunology Research 2 (2014): 320-331.

- Arrieta O, Montes-Servín E, Hernandez-Martinez JM, et al. Expression of PD-1/PD-L1 and PD-L2 in peripheral T-cells from non-small cell lung cancer patients. Oncotarget 8 (2017): 101994-102005.

- RoyerL, Chauvin M, Dhiab J, et al. Vallet, Expression of immune checkpoint on subset of monocytes in old patients. Experimental Gerontology 181 (2023): 112267.

- Jin S, Xu B, Yu L, et al. The PD-1, PD-L1 expression and CD3+ T cell infiltration in relation to outcome in advanced gastric signet-ring cell carcinoma, representing a potential biomarker for immunotherapy. Oncotarget 8 (2017): 38850-38862.

- Vago L, Gojo I. Immune escape and immunotherapy of acute myeloid leukemia. The Journal of Clinical Investigation 130 (2020): 1552-1564.

- Amberger DC, Schmetzer HM. Dendritic Cells of Leukemic Origin: Specialized Antigen-Presenting Cells as Potential Treatment Tools for Patients with Myeloid Leukemia, Transfusion medicine and hemotherapy 47 (2020): 432-443.

- Atzler M, Rank A, Inngjerdingen M, et al. Increased detection of (leukemiaspecific) adaptive and innate immune-reactive cells under treatment of AML-diseased rats and one therapy-refractory AML-patient with blastmodulating, clinically approved response modifiers. European Journal of Cancer 110 (2019): S28-S29.

- Chen C, Liang C, Wang S, et al. Expression patterns of immune checkpoints in acute myeloid leukemia. Journal of Hematology & Oncology 13 (2020).

- Ruan Y, Wang J, Zhang Q, et al. Clinical implications of aberrant PD-1 expression for acute leukemia prognosis. European Journal of Medical Research 28 (2023): 383.

- Li Y, Chen C, Liang C, et al. 3103 – Optimal Combination of Immune Checkpoints Predicts Adverse Outcomes in Patients with Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Experimental Hematology 88 (2020): S70.

- Li C, Xiao M, Geng S, et al. Comprehensive analysis of human monocyte subsets using full-spectrum flow cytometry and hierarchical marker clustering. Frontiers in Immunology 15 (2024).

- Knaus HA, Berglund S, Hackl H, et al. Signatures of CD8+ T cell dysfunction in AML patients and their reversibility with response to chemotherapy. JCI Insight 3.

- Williams P, Basu S, Garcia-Manero G, et al. The distribution of T-cell subsets and the expression of immune checkpoint receptors and ligands in patients with newly diagnosed and relapsed acute myeloid leukemia. Cancer 125 (2018): 1470-1481.

- Duraiswamy J, Ibegbu CC, Masopust D, et al. Phenotype, Function, and Gene Expression Profiles of Programmed Death-1hi CD8 T Cells in Healthy Human Adults. Journal of Immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 186 (2011): 4200-4212.

- Kamphorst AO, Pillai RN, Yang S, et al. Proliferation of PD-1+ CD8 T cells in peripheral blood after PD-1-targeted therapy in lung cancer patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 114 (2017): 4993-4998.

- Zheng H, Liu X, Zhang J, et al. Expression of PD-1 on CD4+ T cells in peripheral blood associates with poor clinical outcome in non-small cell lung cancer. Oncotarget 7 (2016): 56233-56240.

- van de Ven R, Niemeijer ALN, Stam AG, et al. High PD-1 expression on regulatory and effector T-cells in lung cancer draining lymph nodes. ERJ Open Research 3 (2017).

- Canaday DH, Parker KE, H. Aung, et al. Age-dependent changes in the expression of regulatory cell surface ligands in activated human T-cells, BMC Immunology 14 (2013): 45.

- Sharpe AH, Wherry EJ, Ahmed R, et al. The function of programmed cell death 1 and its ligands in regulating autoimmunity and infection. Nature Immunology 8 (2007): 239-245.

- Abaza Y, Zeidan AM. Immune Checkpoint Inhibition in Acute Myeloid Leukemia and Myelodysplastic Syndromes. Cells 11 (2022).

- Chen Y, Mu CY, Huang JA, et al. Clinical significance of programmed death-1 ligand-1 expression in patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a 5-year-follow-up study, Tumori 98 (2012): 751-755.

- Loacker L, Kimpel J, Bánki Z, et al. Increased PD-L1 surface expression on peripheral blood granulocytes and monocytes after vaccination with SARS-CoV2 mRNA or vector vaccine. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine 61 (2023): e17-e19.

- Jimbu L, Mesaros O, Neaga A, et al. The Potential Advantage of Targeting Both PD-L1/PD-L2/PD-1 and IL-10–IL-10R Pathways in Acute Myeloid Leukemia, Pharmaceuticals 14 (2021).

- Zajac M, Zaleska J, Dolnik A, et al. Expression of CD274 (PD-L1) is associated with unfavourable recurrent mutations in AML. British Journal of Haematology 183 (2018): 822-825.

- Silva M, Martins D, Mendes F, et al. The Role of Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Onco (2022) 164-180.

- Goleva E, Lyubchenko T, Kraehenbuehl L, et al. Our Current Understanding of Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy in Cancer Immunotherapy. Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology: Official Publication of the American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology 126 (2021): 630-638.

- Damiani D, Tiribelli M. Checkpoint Inhibitors in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. Biomedicines 11 (2023).

- Berthon C, Driss V, Liu J, et al. In acute myeloid leukemia, B7-H1 (PD-L1) protection of blasts from cytotoxic T cells is induced by TLR ligands and interferon-gamma and can be reversed using MEK inhibitors. Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy: CII 59: (2010) 1839-1849.

- Lim TS, Chew V, Sieow JL, et al. PD-1 expression on dendritic cells suppresses CD8+ T cell function and antitumor immunity. Oncoimmunology 5 (2016): e1085146.

Impact Factor: * 5.8

Impact Factor: * 5.8 Acceptance Rate: 71.20%

Acceptance Rate: 71.20%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks