Influence of Inflammation on Tendon Healing and The Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma

Ferran Abat1*, Rodrigo Arancibia2, Paul Teran3, Matias Roby4, Jose Estay2, Solange Rivas2, Manel M. Santafe5

1Sports Orthopaedic Department. ReSport Clinic. Blanquerna Health Sciences Faculty, Ramon Llull University, Barcelona. Spain

2Cellus Biomédica, León Technology Park. León, Spain

3Centro de Especialidades Ortopédicas - Hospital Metropolitano. Quito Ecuador

4Innovation Center, Clinica MEDS, Santiago, Chile

5Unit of Histology and Neurobiology, Department of Basic Medical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine and Health Sciences, Rovira i Virgili. University, Spain

*Corresponding Author: Ferran Abat, Sports Orthopaedic Department. ReSport Clinic. Blanquerna Health Sciences Faculty, Ramon Llull University, Barcelona. Spain.

Received: 20 November 2025; Accepted: 27 November 2025; Published: 12 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Ferran Abat, Rodrigo Arancibia, Paul Teran, Matias Roby, Jose Estay, Solange Rivas, Manel M. Santafe. Influence of Inflammation on Tendon Healing and The Use of Platelet-Rich Plasma. Journal of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine 7 (2025): 556-568.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

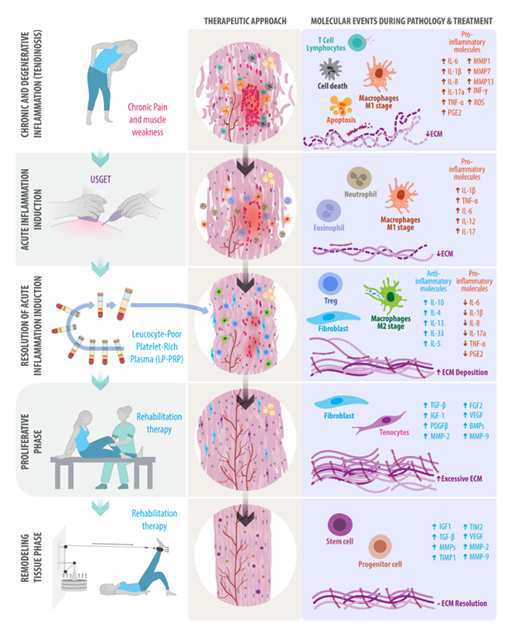

Tendon injuries may result from acute trauma or chronic overuse and typically present with pain, inflammation, weakness, and stiffness. These conditions often fail to resolve with rest alone and usually require a multimodal treatment approach. Among the available strategies, plateletrich plasma (PRP) and ultrasound-guided electrolysis (USGET) have shown significant potential to enhance the body's intrinsic healing mechanisms. However, the efficacy of PRP depends critically on the preparation method and the specific inflammatory context in which it is applied. Acute inflammation is a rapid and controlled response that initiates the healing cascade. In contrast, persistent, unresolved inflammation leads to chronic inflammation, fibrosis, and degenerative changes, affecting biomechanical properties and adjacent tissues, as seen in chronic tendinopathies.

This review summarizes the cellular and molecular mechanisms underlying tendon repair, with a focus on the spatiotemporal interplay of inflammatory mediators and growth factors during acute and chronic inflammation. We also examine the mechanistic rationale and clinical evidence for PRP and USGET, alone and in combination, across different tendinopathies. Although no consensus exists regarding the superiority of either PRP or USGET as stand-alone treatments, we propose that, in chronic tendinopathies, physical stimulation of fibrotic tissue by USGET, followed by PRP infiltration and eccentric exercises, may reactivate the healing cascade and support each phase of the repair process. This approach has shown promising results in refractory tendon injuries, offering distinct advantages over conservative treatments. Emerging clinical data suggest that this integrative approach provides advantages over conservative therapies in refractory tendon injuries.

Keywords

<p>Platelet-rich plasma; Ultrasound-guided electrolysis; Tendinopathy; Tendon repair; Healing cascade</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

The ability of platelets and their associated growth factors to promote tissue repair has generated increasing interest in musculoskeletal medicine. However, the clinical effectiveness of these orthobiologic therapies depends strongly on the inflammatory context in which they are applied [1]. In acute tendinopathy, inflammation is typically rapid and self-limited, supporting tissue repair. In contrast, chronic tendinopathy is characterized by a failed healing response, persistent inflammation, and progressive matrix degeneration [2]. In recent years, platelet-rich plasma (PRP) and physical therapies such as extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) and ultrasound-guided electrolysis (USGET) have emerged as promising options for the management of tendinopathies [3,4]. These treatments may modulate specific phases of the tendon healing cascade, particularly by influencing the balance between pro- and anti-inflammatory mediators and the quality of extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling.

This review aims to (i) summarize the subcellular mechanisms involved in tendon healing and in the transition from acute to chronic inflammation; (ii) discuss how different PRP formulations and USGET can modulate these mechanisms; and (iii) propose a rationale for combining USGET with PRP and eccentric exercise in chronic tendinopathies. We also highlight the importance of the spatiotemporal delivery of these interventions to maximize tendon repair and minimize fibrosis and reinjury.

This review presents the best evidence on the cellular and molecular factors involved in tendon repair, including selected in vitro, in vivo, and randomized controlled trials, as well as meta-analyses from high-impact journals. It highlights the evidence for PRP, ESWT, and USGET in each stage of tendon repair.

2. Healthy Tendon: Functions and Cellular Components

A tendon connects a muscle to a bone, allowing the transmission of muscle force to generate movement, stabilize joints, store energy, and adapt to mechanical loads. A tendon is a dense, regular fibrous connective tissue composed mainly of tendon stem/progenitor cells (TSPCs), specialized fibroblasts known as tenocytes, and an extracellular matrix (ECM) rich in type I collagen, elastin, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins. A delicate balance between proinflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators within this matrix is essential to maintain tissue homeostasis and preserve normal tendon function (Figure 1) [5]. The ECM plays a crucial role in the healing of tendon injuries, providing structural support and initiating and controlling the transmission of biochemical and biomechanical signals essential to tissue homeostasis [6].

3. The Physiological Healing Cascade in Tendon Injuries

The healing of ruptured tendons follows a predictable series of three overlapping phases: (1) reparative inflammation, (2) proliferation and extracellular matrix (ECM) production, and (3) tissue remodeling. The duration and quality of each phase depend on the injury site and the severity of the damage [7].

Inflammation and initial repair

In the initial stage of a tendon lesion, platelets induce the proinflammatory cascade, releasing TNFα, IFNγ, IL1β, and nitric oxide synthase inducible (iNOS), with the recruitment of type I-associated immune cells such as Th1 T-cells, neutrophils, and M1-macrophages [8], followed by the increase of regulatory T lymphocytes (Tregs), which mediate a shift from type 1 (proinflammatory) to type 2 (anti-inflammatory) responses. M2-polarized macrophages and Tregs facilitate the ECM deposition and the secretion of growth factors that induce a proliferative and regenerative microenvironment, including the recruitment of resident stem and progenitor cells [2,9]. Evidence suggests that a balance of type 1 and type 2 immune responses is crucial to prevent chronic inflammation and tissue degeneration [10].

Proliferation and synthesis of ECM

After several days, when the inflammation has subsided, M2 macrophages produce anti-inflammatory molecules such as TGF-β1, IL-4, and IL-10, which are necessary to initiate the proliferative phase and ECM synthesis. TGF-β1 and Wnt3a promote proliferation and migration, which are required for granulation tissue formation [11]. Additionally, M2 macrophages secrete metalloproteinases, specifically MMP-2 and MMP-9, which facilitate the degradation of the old ECM. After cellular detritus has been cleared, fibroblasts and tenocytes synthesize abundant ECM, primarily collagen type III, which is randomly arranged, with increased numbers of new vessels. This stage also features increased cellularity and increased water absorption [12].

Remodeling and maturation

Tissue remodeling enables macrophages and fibroblasts to restore tissue architecture, thereby helping restore tissue strength and integrity. It includes two sub-stages and begins 6 to 8 weeks after the injury, lasting up to 1 year to generate mature fibers (collagen type I). Collagen fibers realign, thereby increasing tensile strength. Due to the irregular arrangement of fibers, scar tissue has 80% of the strength of normal tissue [13,14]. The balance between matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) and their tissue inhibitor proteins (TIMPs) is crucial to prevent excessive matrix degradation and fibrosis [15].

4. Interplay of Molecules and Signaling Pathways in Acute and Chronic Inflammation

Acute Inflammation

Acute inflammation is a rapid, reparative response to tissue injury, characterized by the release of histamines, prostaglandins, and leukocytes [16]. These mediators increase vascular permeability and facilitate the infiltration of inflammatory cells, such as neutrophils and macrophages [17]. Growth factors released by platelets, such as TGF-β1 and PDGF, stimulate cell proliferation and ECM synthesis [18]. Additionally, matrix metalloproteinase inhibitors, such as TIMP-1 and TIMP-2, play a critical role in regulating granulation tissue remodeling and facilitating proper tissue repair [15]. Among the most prominent are IL-6, TNF-α, TGF-β, and VEGF, which play a crucial role in mediating and resolving inflammation (Table 1). A subgroup of Achilles tendinopathy patients with elevated IL-6 levels showed a poorer response to physiotherapy. Additionally, IL-6/JAK/STAT signaling activates tendon fibroblast populations, initiating and exacerbating the hallmarks of tendinopathy [19]. TNF-α can strongly activate tenocytes by inhibiting the expression of the proapoptotic Fas ligand in Achilles tendinopathy [20], and TNF-α polymorphisms (308 G>A) could influence the susceptibility to developing tendinopathy among athletes [21]. During acute tendinopathy, signaling pathways such as mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), including ERK1/2, contribute to a healthy healing response by stimulating cell proliferation and migration. However, in chronic conditions, persistent and excessive activation of NF-κB and MAPK pathways is associated with ongoing tendon damage and impaired structural integrity [22]. Indeed, experimental models have shown that inhibiting these pathways can attenuate the severity of Achilles tendinopathy [23].

Chronic Inflammation

Chronic inflammation is characterized by the persistent presence of inflammatory cells, mainly macrophages and T lymphocytes, and the continuous production of inflammatory mediators [24] (Table 1). This response results in tissue damage and fibrosis, impeding the effective repair. Gene expression associated with chronic inflammation includes IL-1β, TNF-α, and MMPs, which can degrade the ECM and perpetuate an unresolved inflammation [25]. IL-1β plays an essential role in degrading the ECM, inhibiting tendon cell markers, and inducing pain, thereby impairing TSPCs' function and inhibiting tendon repair capacity. Thus, decreased IL-1β may be beneficial for maintaining TSPC function during tendon repair [26,27].

The well-known signaling pathway in chronic tendinopathy is the JAK/STAT pathway, which perpetuates the inflammation and fibrosis. Abnormal activation of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway contributes to tendinopathy by impairing TSPC function [28,29]. The imbalance of pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine levels, along with MMPs and TIMP levels, is the primary molecular driver of chronic inflammation [30]. Other relevant signaling pathways in chronic tendinopathy include proinflammatory pathways such as NF-κB, p38/MAPK, and the NLRP3 inflammasome, which contribute to the release of proinflammatory mediators, pain, and tissue degradation. Mechanotransduction pathways, such as the integrin-FAK/Src and YAP/TAZ pathways, also regulate cellular responses to mechanical stress. These pathways typically help tenocytes to adapt to mechanical loading rather than contributing to chronic inflammation, failed matrix repair, and ectopic tissue formation [26].

Chronic Tendinopathies represent a failed tendon healing

Chronic tendinopathy, also known as tendinosis, is characterized by the absence of reparative inflammation, disorganization of collagen fibers, and an active degenerative process in the collagenous matrix, accompanied by hypercellularity, apoptosis, and elevated levels of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), as well as disordered neovascularization attributed to hypoxia and excessive mechanical loading. Consequently, the tendon thickens and stiffens to overcome the lower mechanical strength; hence, the tendon quality and its functional activity are reduced [31]. Therefore, mechanical properties are weakened due to maladaptive responses to compressive loading, and mechanobiological overstimulation marks the onset of degenerative disease [32].

|

Acute tendinopathy (reactive process) |

Chronic tendinopathy (degenerative process) |

|

|

Signs and Symptoms |

Sudden, sharp pain, swelling, and tenderness at the affected tendon, often due to overuse or injury. |

Gradual onset of pain, stiffness, and weakness, with less inflammation compared to acute cases. Dull, aching pain that worsens with activity and can persist even at rest, and decreased range of motion. |

|

Tendon characteristics |

Marked disorganization and fragmentation of collagen fibers, loss of tensile strength, hypercellularity with areas of apoptosis, neovascularization, and fibrosis; acute inflammation is usually absent. |

|

|

Cytokines |

IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12, IL-17. |

IL-1β, IL-6, IL-8, Il-10 (persistence). |

|

Growth Factors and Signaling Pathways |

TNF-α, IFN-γ, IGF-I, TGF-β, bFGF, MMP13, JAK-SHP2-MAPK, JAK-AKT, and JAK-STAT3, as well as NF-κB signaling pathways, are activated by TNF-α and IL-1β. |

IGF-1, VEGF, PDGF, TGF-β. JAK-STAT3, NF-κB, integrin-FAK/Src, and YAP/TAZ signaling pathways. |

Table 1: Cellular and molecular characteristics of chronic and acute tendinopathy.

5. The Importance of Temporal-Spatial Molecule Expression in Tendon Healing

Through the tendon healing cascade, the expression and interaction of various molecules within the tendon change both in abundance and in their specific locations. Understanding these temporal and spatial variations is essential for developing personalized treatments for tendinopathies [28].

Variations in gene expression throughout tendon healing

The transcription factor Scleraxis (Scx) is a critical regulator of tendon formation. Tendon injury, which expresses Scx exclusively, follows differentiation from native tendon to reactive tissue, influenced by interactions with inflammatory mediators [33]. While this process is crucial for the proper initiation of tendon healing, deregulated inflammation can lead to fibrosis. Indeed, several transcription factors predicted to mediate the reactive phase are strongly associated with tissue fibrosis, including aberrant Egr1 expression. Instead of NF-κB signaling declining to prevent excessive inflammation, Egr1 induced the expression of Rela and Nfkb1, both NF-κB subunits [34]. In cases where NF-κB and Egr1 expression remain elevated rather than returning to baseline after an injury, they promote a persistent, pro-fibrotic environment, leading to a loss of mechanical strength and an increased risk of reinjury [35]. In the initial stages, the imbalance between MMPs and TIMPs has been linked to collagenolysis, potentially increasing the risk of reinjury. However, the overall decrease in MMP13 expression occurred later, reflecting a return to homeostatic tension as the repair tissue matures, or the reestablishment of a homeostatic set point by contractile tendon cells [36]. Even some studies suggest that different tendons, such as the digital flexor, triceps, and supraspinatus tendons, exhibit distinct growth factor profiles after similar injuries [37,38].

Chronic Achilles tendinopathy is characterized by low TGF-β expression; however, the addition of growth factors activates signaling pathways in tendon fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and macrophages, leading to increased TGF-β expression only during the first two weeks of the healing process. This upregulation supports collagen synthesis, neovascularization, immune tolerance, and decreased inflammation [39]. Supraspinatus tendon-to-bone healing has been shown to exhibit early TGF-β expression at the first week, accompanied by increases in Bone Morphogenetic Protein 12 (BMP-12), cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP), and connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) later in the healing process, and at the insertion site [38]. PDGF-BB significantly enhances type I collagen synthesis, highlighting its role in the expression and regeneration of native and functional tissue [40]. For example, the administration of PDGF in tendons has demonstrated remarkable enhancements in their biomechanical behavior [41].

Recently, the tendon-healing process has been enhanced by delivering chemically modified mRNAs using injectable nanoparticles in vivo, targeting specific anti-inflammatory and regenerative pathways, including IL-1βRA and PDGF-BB [42]. The infiltration of anti-inflammatory and reparative biological molecules, such as IL-1βRA and PDGF-BB, respectively, may improve two key steps in the physiological repair process. However, using one or two molecules is not enough for long-term effectiveness.

PRP contains a cocktail of key cytokines and growth factors for tissue healing. The physical therapy that utilizes a galvanic electrical current, known as ultrasound-guided galvanic electrolysis technique (USGET), Ultrasound-Guided Percutaneous Electrolysis (UGPE) or simply Percutaneous Electrolysis (PE), among others, is well known to modulate the balance of temporal and spatial factors required at each step of the healing process, including significant immunomodulatory effects that are pivotal in orchestrating the immune response during wound healing [43,44]. Additionally, PRP and USGET have been shown to reduce reinjury rates after treatment compared with controls [45-48]. We presented here their mechanism of action and how they impact the biology of the healing cascade, along with the latest clinical evidence.

6. Mechanisms of Action of PRP as a Driver of Tendon Repair

PRP: PRP is an autologous blood-derived product that concentrates platelets and their associated growth factors, including PDGF, TGF-β, HGF, VEGF, FGF-2, EGF, and TNF-α, as well as cytokines such as IL-6, IL-1Ra, and IL-8. These molecules enhance the activity of tendon stem/progenitor cells and tenocytes [49,50], induce a controlled and transient inflammatory response [33], and promote cell proliferation, angiogenesis, and ECM synthesis [51,52]. Additionally, PRP protects tenocytes from oxidative stress-induced cell death by activating the Nrf2 pathway, thereby helping to restore tenocyte homeostasis and promoting tendon regeneration and repair [53,54]. The first study of PRP in tendinopathy suggests its ability to stimulate tissue repair by increasing the expression of TGF-β1 and PDGF-BB, as well as the matrix molecules collagen type I (COL1A1), collagen type III (COL3A1), and COMP, without concomitant increases in the catabolic MMP-3 and MMP-13 [55]. The cocktail of molecules in PRP influences various phases of tendon repair, including inflammation, proliferation, and remodeling, by releasing growth factors that stimulate cell proliferation and ECM formation [55,56]. However, when analyzing more than 25 studies reporting platelet counts, it is observed that platelet counts greater than 3.2 × 109 have generally yielded more positive results [57].

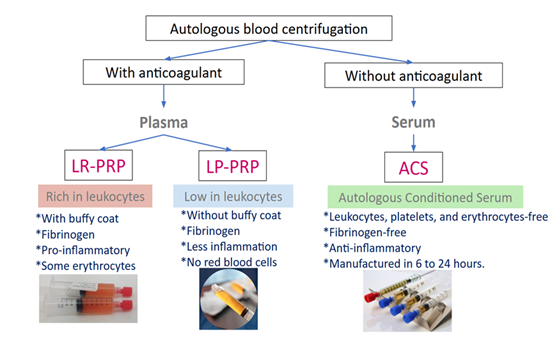

The benefit of PRP in treating tendinopathies lies in its concentration and in the various PRP preparations available to address different characteristics of the lesion (e.g., vascularized vs. non-vascularized lesions) and stages of tendon healing, which are based on platelet concentration, leukocyte levels, and activation methods. PRP preparations can be classified into leukocyte-rich PRP (LR-PRP), leukocyte-poor PRP (LP-PRP), and the acellular product, serum-rich in growth factors (ACS) (Figure 2) [58].

LR-PRP: In LR-PRP therapy, leukocytes release inflammatory cytokines that activate inflammation, increasing the TGF-β to restart the healing process, providing benefits for acute tendinopathy [59]. A randomized, double-blind, controlled clinical trial involving 47 patients with patellar tendinopathy demonstrated that LR-PRP significantly improved knee function and pain scores compared with the extracorporeal shock wave therapy group. Additionally, the PRP treatment has allowed patients to return to the initial stage of patellar tendinopathy [60]. Numerous clinical trials and meta-analyses have demonstrated strong evidence supporting the efficacy of a single injection of LR-PRP guided by ultrasound for the treatment of tendinopathies [61]. However, when the tendon has become fibrotic, physical therapy, such as electrotherapy, must be included in the initial stage of treatment, as a high concentration of leukocytes alone is insufficient to reset the healing process.

LP-PRP: PRP low in leukocytes avoids an excessive catabolic and inflammatory response to benefit the proliferative state of the healing. In chronic injuries, LP-PRP aims to minimize additional inflammation while promoting rapid healing [59,62] by modulating the MMP/TIMP balance [59]. To achieve the right balance between enhanced healing and minimizing scar tissue formation, LP-PRP stands out as a compelling solution. A meta-analysis of 10 RCTs involving 742 patients found that leukocyte-poor PRP significantly reduces the postoperative retear rate in both the short- and long-term, regardless of tear size or repair method [63].

Autologous Serum Rich in Growth Factors (ACS): ACS is an acellular treatment, without coagulation factors or leucocytes, so it contains high concentration of anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, IL-13 y IL-1Ra) and tissue repair proteins (TIMP-1, TIMP-2, VCAM-1, PDGF-BB), with higher concentrations of IGF-1, TNF-alpha, especially IL-1Ra and PDGF-BB compared to PRP [64]. Consequently, ACS could be another alternative for persistent tendinopathies. A clinical trial involving 50 patients with tendinopathy demonstrated that ACS provides greater long-term clinical benefits than eccentric training [65]. In addition, ACS was associated with significantly better pain control and functional outcomes than corticosteroids in chronic supraspinatus tendinopathy [66]. ACS has demonstrated superior efficacy in managing chronic inflammation compared with PRP, due to elevated levels of anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1Ra, IL-4, and IL-10 [67]. However, because its preparation requires more than 24 hours, it is used less frequently [68].

Clinical applications of PRP in tendinopathies

PRP has demonstrated its efficacy in different tendinopathies due to its capacity to stimulate and potentiate the physiological healing process. Among the most studied tendinopathies, highlights:

Patellar Tendinopathy: LR-PRP has shown efficacy in treating patellar tendinopathy [69]. Seventy studies involving 2,530 patients were included in a meta-analysis, showing an overall positive outcome, with eccentric exercises as the strategy of choice in the short term. Still, multiple PRP injections may offer more satisfactory results at long-term follow-up [70]. Another study evidenced that after LR-PRP treatment, patients with patellar tendinopathy showed statistically significant and clinically meaningful improvement for 1 year compared with needle tenotomy and sham, as assessed by quantitative ultrasound and MRI [71]. Notably, only those who had not previously received ethoxysclerol, cortisone, or surgical treatment experienced better results [72].

Achilles Tendinopathy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials involving 406 patients found that eco-guided PRP injection demonstrated good efficacy for chronic Achilles tendinopathy [73]. Additionally, another meta-analysis of PRP based on randomized controlled trials showed significant improvements in ankle dorsiflexion angle, ankle dorsal extension strength, and calf circumference compared with control groups [74]. Furthermore, the use of ACS appears to provide greater long-term clinical benefits than eccentric training [65]. Otherwise, evidence also indicates no superiority of PRP over placebo in 4 RCTs [75]. Although one those studies conducted a follow-up for only 3 months [62], it is a short-term assessment of PRP efficacy. Another did not activate the PRP [62], a crucial step for its effectiveness in treating tendinopathies [76]. The last study did not mention using ultrasound to guide infiltration [63]. Ultrasound-guided injections are more accurate than blind injections in achieving therapeutic efficacy [77,78]. However, the current understanding of Achilles tendinopathy indicates limited evidence regarding the effectiveness of infiltrative therapies. A multimodal treatment approach is a good choice in cases of non-therapy response.

Rotator Cuff Injuries: For arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, LP-PRP has been utilized to enhance postoperative healing and alleviate postoperative pain [79]. A randomized controlled study demonstrated that LR-PRP improves clinical outcomes and reduces pain in patients with chronic rotator cuff tendinopathy [80]. Additionally, PRP and ACS have shown higher efficacy than corticosteroid infiltration [66,81,82]. There is strong evidence supporting the effectiveness of PRP in different stages of rotator cuff healing.

Lateral Epicondylitis (Tennis Elbow): PRP has demonstrated greater efficacy than corticosteroids in meta-analyses of RCTs. These studies suggest that PRP offers superior long-term benefits in pain reduction and improved functionality [83,84]. Additionally, further evidence from other RCTs continues to support the superior efficacy of PRP compared to corticosteroids [81,85]. However, most of these studies did not provide details on how the PRP was prepared.

In a meta-analysis evaluating the use of PRP in the musculoskeletal field, only 11 out of 105 clinical studies (10%) provided a comprehensive report on the PRP preparation protocol. Additionally, only 17 studies (16%) reported the composition of the platelet-rich plasma preparation [86].

7. Mechanisms of Action of USGET as a Driver of Tendon Repair

Ultrasound-guided electrolysis (USGET) is a minimally invasive electrotherapy technique that uses a galvanic current delivered through an ultrasound-guided acupuncture needle, with a dosage of 3 to 6 milliAmps. Electrolysis refers to the decomposition of water (H2O) and sodium chloride (NaCl) present in tissues. This controlled decomposition promotes tissue repair. This process occurs when a galvanic current is applied, causing these substances to decompose into their constituent chemical elements. These elements recombine to form new substances: sodium hydroxide (NaOH), hydrogen (H), and chloride (Cl) [87]. It induces specific electrochemical reactions at the cellular level in affected tissues, resulting in controlled microtrauma and non-thermal electrochemical ablation directly in the degenerated tendon area, triggering reparative inflammation and angiogenesis [4,88,89]. Additionally, this promotes phagocytosis and tendon healing by producing new collagen fibers and inhibiting proinflammatory factors [76], as well as by overexpressing the activated gamma receptor for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR-gamma). Furthermore, it inhibits the actions of IL-1β, TNF, and COX-2 by directly inhibiting NF-κB [89].

In the USGET, the galvanic current creates two distinct electrochemical environments in the tissue: an alkaline environment at the cathode (the needle tip) and an acidic environment at the anode (the skin surface electrode), both of which are crucial to its therapeutic effect.

The principal reactions include:

Electrolysis of water: The galvanic current applied through the needle dissociates water into hydrogen ions (H+) and hydroxide ions (OH-). This reaction produces reactive oxygen species (ROS) and free radicals, which play a crucial role in cell signaling and induce a localized inflammatory response [87].

Ion production: Electrolysis also dissociates salts and other molecules present in the extracellular environment into their constituent ions. For example, the dissociation of sodium chloride (NaCl) produces sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl-) ions, which contribute to local pH alterations and the activation of enzymes and other bioactive molecules [87].

Generation of free radicals: The free radicals generated during electrolysis cause controlled damage to cells and tissues, triggering the release of growth factors and activating repair mechanisms. These radicals include reactive oxygen species, hypochlorite (ClO−), and hypochlorous acid (HClO), which possess antimicrobial and denaturing properties [90].

Redox reactions: The galvanic current also induces oxidation-reduction (redox) reactions in the tissue. These reactions can modify the structure of proteins and other molecules, facilitating the degradation of damaged components and promoting the synthesis of new materials for tendon repair [87,90]

USGET as a controlled proinflammatory trigger

The effects of USGET are dose-dependent: excessive current intensity or duration can cause unwanted cell damage and necrosis, which underscores the need for precise parameter selection [87]. When properly applied, the galvanic current generates a localized electric field that transiently disrupts cellular homeostasis and elicits a controlled inflammatory response, activating macrophages, stimulating fibroblast proliferation, and promoting ECM remodeling, particularly in fibrotic lesions resulting from persistent chronic inflammation. Galvanic current has been shown to activate the NLRP3 inflammasome, a key regulator of inflammation, eliciting a transient IL-1β/IL-18 response that primes tissue remodeling. This process is also associated with the activation of the proinflammatory M1-macrophage phenotype. The matrix reorganization is also promoted, with a shift toward type I collagen and a reduction in type III collagen, aligning with the restoration of a more mechanically robust tendon matrix [91]. Also, evidence indicates that USGET triggers cellular apoptosis by activating caspases and releasing Smac/Diablo proteins from the mitochondria into the cytosol, thereby facilitating tissue repair by eliminating damaged cells and promoting a more efficient regeneration process [89]. Therefore, USGET may be the therapeutic option that initiates the healing cascade.

Clinical applications of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT), and USGET therapy in tendinopathies

Unlike USGET, ESWT uses mechanical shockwaves to break down tissue and stimulate tissue healing. In contrast, USGET employs a fine needle to deliver an electric current to a specific tissue under ultrasound guidance. ESWT delivers high-energy sound waves to the affected tissue at frequencies ranging from 0 to 20 MHz. ESWT can be a highly effective therapy option for relieving pain in individuals with tendinopathy, stimulating healing, and promoting the release of growth factors and neovascularization at the tendon–bone junction [92,93]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that ESWT was effective in alleviating pain associated with rotator cuff tendonitis, lateral epicondylitis, finger tendonitis, and long bicipital tendonitis. Interestingly, the efficacy of ESWT was compared with that of PRP infiltration for jumper's knee and plantar fasciitis, showing improved outcomes in the PRP group that were even superior to those of corticosteroid infiltration [94,95].

Patellar tendinopathy: A RCT with a duration of 10 years provided evidence that the USGET, combined with eccentric exercises, shows an effective and consistent improvement in symptoms of chronic patellar tendinopathy [96], yielding better outcomes than conventional electrophysiotherapy by destroying the degenerated tissue and causing a controlled inflammatory response that triggers the biological process of collagen repair [48]. In a 3-year follow-up study, the USGET restores functionality and decreases pain over time. The significant clinical improvement was confirmed by increases in scores on the VISA-P, IKDC, Kujala, and Tegner activity scales [97].

Distal bicep tendon: The distal biceps tendon has two heads that rotate and insert into the radial tuberosity, making it challenging to visualize and access fully with ultrasound. A recent protocol using US guidance has been shown to be safe for USGET of the distal biceps brachii tendon in insertional tendinopathies [98].

Supraspinatus tendinopathy: Forty-six participants were randomly allocated to USGET, percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation, and eccentric exercise, or a conventional physical therapy group. The combined intervention provided safe and effective treatment, resulting in statistically significant improvements in pain, mobility, and function compared with conventional electrotherapy [99]. In addition, USGET seems to be more effective than trigger point dry needling in relieving pain and improving shoulder range of motion, as well as point pressure pain threshold values in the supraspinatus, both right after treatment and at one-year follow-up [100]. USGET enhances shoulder function, alleviates pain, and facilitates the resorption of calcific deposits [101].

Rotator Cuff Partial Tear: Fifty-five patients were randomized to ESWT with PRP injection and PRP in isolation. The combination showed notable additional improvements in both forward flexion (p = 0.033) and abduction (p = 0.015) after 1 month. Furthermore, a substantial augmentation in the range of shoulder motion (SROM) (p < 0.001) was observed after six months. The combination of ESWT with PRP injection may offer advantages over PRP injection alone [3]. This groundbreaking study highlights the remarkable effectiveness of combining PRP with physical stimulation, paving the way for innovative applications of both PRP and USGET.

Chronic soleus injury: USGET combined with an eccentric exercise program is a valuable therapeutic tool for treating chronic soleus injury in the central tendon [102].

Achilles tendinopathy: Patients were randomly assigned to two groups that received the same physiotherapy treatment. The experimental group, which received three USGET stimulations, demonstrated statistically significant improvements compared to the control group. Specifically, they showed superior results in the VISA-A score (p = 0.010) and its subscales, as well as in the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain (p = 0.002), overall pain (p = 0.004), functional ability (p = 0.003), and sports-related activities (p = 0.002). No adverse events were reported during the study. In patients with Achilles tendinopathy, USGET has been shown to reduce pain, increase range of motion (ROM), and decrease morning stiffness, especially when combined with eccentric exercises [103].

Chronic Lateral Epicondylitis: In the clinical trial NCT02085928, 36 patients received USGET associated with a home program of eccentric exercises and stretching. The ultrasonographic findings revealed significant changes in the hypoechoic regions and hypervascularity of the extensor carpi radialis brevis. At 26 and 52 weeks, all participants perceived a 'successful' outcome, and recurrence rates were absent at follow-up at 6, 26, and 52 weeks [104].

In 2023 and 2024, relevant meta-analyses demonstrated the efficacy of USGET in tendinopathies, particularly in reducing pain and improving function, when combined with exercises. It can eliminate fibrotic tissue that causes nerve entrapment, providing pain relief and improved function. USGET has shown consistent results in treating specific tendinopathies, including chronic lateral epicondylitis (tennis elbow), patellar tendinopathy (jumper's knee), and Achilles tendinopathy [4,44,105,106].

8. Clinical Practice Implications

Tendon healing is poorly understood, and the outcomes of conservative and surgical management are often suboptimal. The efficacy of PRP and USGET, summarized here, represents a promising area of research in regenerative medicine, particularly in cases of misrepair involving fibrotic tissue, where PRP alone is often insufficient to restore a physiological healing response [107]. These lesions may first require inflammatorystimulation through USGET to disrupt fibrotic tissue and reactivate a controlled inflammatory phase. Subsequently, PRP can be applied to modulate this renewed inflammatory response, support organized ECM deposition, and enhance the release of endogenous growth factors (Figure 3) [108]. When combined with an appropriate physical therapy protocol to enhance biomechanics through an eccentric exercise program, this strategy may offer a more comprehensive and durable solution than any single modality alone.

9. Concluding Remarks and Final Recommendations

Understanding the subcellular physiology of connective tissues and the differences between acute and chronic inflammation is crucial for platelet activation and tissue repair. Utilizing techniques such as USGET and PRP, or in combination, may improve clinical outcomes in patients with different tendinopathies (Figure 3).

Combining physical and biological treatments as multimodal therapy offers the advantage of addressing not only the symptoms of the disease—such as pain and functional limitations—but also the underlying biomechanical risk factors and improvement of tissue quality. This comprehensive treatment approach has the potential to enhance effectiveness, shorten recovery time, and decrease the likelihood of recurrence. However, the overall impact of this combined treatment strategy requires validation through rigorous clinical trials [109].

One recent proposal is that combining biological therapies with adjunct inflammatory therapies, such as USGET, particularly for chronic tendinopathies, can enhance treatment efficacy by reactivating the inflammatory process, which PRP can then effectively modulate. This comprehensive approach enables tailored treatments based on the specific inflammatory parameters of the injury, resulting in a quicker and more effective recovery.

Conflict of interest: FA invented the USGET device (OEPM registration n.ES1.247.869U) and receives royalties from GymnaUniphy for scientific consulting and product development. This financial relationship has not influenced the design, conduct, interpretation, or reporting of the research presented in this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Halpern BC, Chaudhury S, Rodeo SA, et al. The role of platelet-rich plasma in inducing musculoskeletal tissue healing. HSS J 8 (2012): 137-145.

- Jiang F, Zhao H, Zhang P, et al. Challenges in tendon-bone healing: emphasizing inflammatory modulation mechanisms and treatment. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 15 (2024): 1485876.

- Kuo SJ, Su YH, Hsu SC, et al. Effects of Adding Extracorporeal Shockwave Therapy (ESWT) to Platelet-Rich Plasma (PRP) among Patients with Rotator Cuff Partial Tear: A Prospective Randomized Comparative Study. J Pers Med 14 (2024).

- Abat F, Alfredson H, Cucchiarini M, et al. Current trends in tendinopathy: consensus of the ESSKA basic science committee. Part II: treatment options. J Exp Orthop 5 (2018): 38.

- Lin TW, Cardenas L, Soslowsky LJ. Biomechanics of tendon injury and repair. J Biomech 37 (2004): 865-877.

- Benjamin M, Kaiser E, Milz S, et al. Structure-function relationships in tendons: a review. J Anat 212 (2008): 211-228.

- Hope M, Saxby TS. Tendon healing. Foot Ankle Clin 12 (2007): 553-567.

- Semple JW, Italiano JE Jr., Freedman J, et al. Platelets and the immune continuum. Nat Rev Immunol 11 (2011): 264-274.

- Arvind V, Huang AH. Reparative and maladaptive inflammation in tendon healing. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 9 (2021): 719047.

- Wang Y, Lu X, Lu J, et al. The role of macrophage polarization in tendon healing and therapeutic strategies: insights from animal models. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 12 (2024): 1366398.

- Gumede DB, Abrahamse H, Houreld NN. Targeting Wnt/ß-catenin signaling and its interplay with TGF-ß and Notch signaling pathways for the treatment of chronic wounds. Cell Commun Signal 22 (2024): 244.

- Diller RB, Tabor AJ. The role of the extracellular matrix (ECM) in wound healing: a review. Biomimetics (Basel) 7 (2022).

- Docheva D, Müller SA, Majewski M, et al. Biologics for tendon repair. Adv Drug Deliv Rev 84 (2015): 222-239.

- Mathew-Steiner SS, Roy S, Sen CK. Collagen in wound healing. Bioengineering (Basel) 8 (2021).

- Del Buono A, Oliva F, Osti L, et al. Metalloproteases and tendinopathy. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 3 (2013): 51-57.

- Abate M, Silbernagel KG, Siljeholm C, et al. Pathogenesis of tendinopathies: inflammation or degeneration? Arthritis Res Ther 11 (2009): 235.

- Everts PAM, Devilee RJJ, Mahoney CB, et al. Platelet gel and fibrin sealant reduce allogeneic blood transfusions in total knee arthroplasty. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand 50 (2006): 593-599.

- Dragoo JL, Braun HJ, Durham JL, et al. Comparison of the acute inflammatory response of two commercial platelet-rich plasma systems in healthy rabbit tendons. Am J Sports Med 40 (2012): 1274-1281.

- Gabay C. Interleukin-6 and chronic inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther 8 (2006): S3.

- Machner A, Baier A, Wille A, et al. Higher susceptibility to Fas ligand–induced apoptosis and altered modulation of cell death by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in periarticular tenocytes from patients with knee joint osteoarthritis. Arthritis Res Ther 5 (2003): R253-R261.

- Lopes LR, Mastalerz A, Cywińska A, et al. Association of TNF-alpha -308G>A polymorphism with susceptibility to tendinopathy in athletes: a case-control study. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil 13 (2021): 51.

- Jiao X, Zhang Y, W, et al. HIF-1α inhibition attenuates severity of Achilles tendinopathy by blocking NF-κB and MAPK pathways. Int Immunopharmacol 106 (2022): 108543.

- Li H, Li Y, Luo S, et al. The roles and mechanisms of the NF-κB signaling pathway in tendon disorders. Front Vet Sci 11 (2024): 1382239.

- Sundman EA, Cole BJ, Fortier LA. Growth factor and catabolic cytokine concentrations are influenced by the cellular composition of platelet-rich plasma. Am J Sports Med 39 (2011): 2135-2140.

- Cavallo C, Roffi A, Grigolo B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma: the choice of activation method affects the release of bioactive molecules. Biomed Res Int 2016 (2016): 6591717.

- Jiang L, Liu T, Lyu K, et al. Inflammation-related signaling pathways in tendinopathy. Open Life Sci 18 (2023): 20220729.

- Zhang K, Asai S, Yu B, et al. IL-1β irreversibly inhibits tenogenic differentiation and alters metabolism in injured tendon-derived progenitor cells in vitro. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 463 (2015): 667-672.

- O’Shea JJ, Plenge R. JAK and STAT signaling molecules in immunoregulation and immune-mediated disease. Immunity 36 (2012): 542-550.

- Seif F, Khoshmirsafa M, Aazami H, et al. The role of JAK-STAT signaling pathway and its regulators in the fate of T helper cells. Cell Commun Signal 15 (2017): 23.

- Minkwitz S, Schmock A, Kurtoglu A, et al. Time-dependent alterations of MMPs, TIMPs and tendon structure in human Achilles tendons after acute rupture. Int J Mol Sci 18 (2017).

- Shahid H, Morya VK, Oh JU, et al. Hypoxia-inducible factor and oxidative stress in tendon degeneration: a molecular perspective. Antioxidants (Basel) 13 (2024).

- Arnoczky SP, Lavagnino M, Egerbacher M. The mechanobiological aetiopathogenesis of tendinopathy: is it the over-stimulation or the under-stimulation of tendon cells? Int J Exp Pathol 88 (2007): 217-226.

- Murchison ND, Price BA, Conner DA, et al. Regulation of tendon differentiation by scleraxis distinguishes force-transmitting tendons from muscle-anchoring tendons. Development 134 (2007): 2697-2708.

- Ackerman JE, Best KT, Muscat SN, et al. Defining the spatial-molecular map of fibrotic tendon healing and the drivers of Scleraxis-lineage cell fate and function. Cell Rep 41 (2022): 111706.

- Liu Z, Fang Y. Wound healing and signaling pathways. Open Life Sci 20 (2025): 20251166.

- Biasutti S, Dart A, Smith M, et al. Spatiotemporal variations in gene expression, histology and biomechanics in an ovine model of tendinopathy. PLoS One 12 (2017): e0185282.

- Gardner BB, He TC, Wu S, et al. Growth factor expression during healing in three distinct tendons. J Hand Surg Glob Online 4 (2022): 214-219.

- Wurgler-Hauri CC, Dourte LM, Baradet TC, et al. Temporal expression of eight growth factors in tendon-to-bone healing in a rat supraspinatus model. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 16 (2007): S198-S203.

- Lyras DN, Kazakos K, Tryfonidis M, et al. Temporal and spatial expression of TGF-β1 in an Achilles tendon section model after application of platelet-rich plasma. Foot Ankle Surg 16 (2010): 137-141.

- Ojima Y, Mizuno M, Kuboki Y, et al. In vitro effect of platelet-derived growth factor-BB on collagen synthesis and proliferation of human periodontal ligament cells. Oral Dis 9 (2003): 144-151.

- Chen Y, Jiang L, Lyu K, et al. A promising candidate in tendon healing events – PDGF-BB. Biomolecules 12 (2022).

- Faustini B, Lettner T, Wagner A, et al. Improved tendon repair with optimized chemically modified mRNAs: combined delivery of PDGF-BB and IL-1Ra using injectable nanoparticles. Acta Biomater 195 (2025): 451-466.

- Patel H, Pundkar A, Shrivastava S, et al. A comprehensive review on platelet-rich plasma activation: a key player in accelerating skin wound healing. Cureus 15 (2023): e48943.

- Gomez-Chiguano GF, Navarro-Santana MJ, Cleland JA, et al. Effectiveness of ultrasound-guided percutaneous electrolysis for musculoskeletal pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Med 22 (2021): 1055-1071.

- Trunz LM, Landy JE, Dodson CC, et al. Effectiveness of hematoma aspiration and platelet-rich plasma muscle injections for the treatment of hamstring strains in athletes. Med Sci Sports Exerc 54 (2022): 12-17.

- Desouza C, Shetty V. Efficacy of platelet-rich plasma in grade II hamstring muscle injuries: results from a randomized controlled trial. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 35 (2025): 259.

- Li Y, Li T, Li J, et al. Platelet-rich plasma has better results for retear rate, pain, and outcome than platelet-rich fibrin after rotator cuff repair: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy 38 (2022): 539-550.

- Abat F, Sánchez-Sánchez JL, Martín-Nogueras AM, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of the ultrasound-guided galvanic electrolysis technique (USGET) versus conventional electrophysiotherapeutic treatment on patellar tendinopathy. J Exp Orthop 3 (2016): 34.

- Jo CH, Kim EJ, Yoon KS, et al. Platelet-rich plasma stimulates cell proliferation and enhances matrix gene expression and synthesis in tenocytes from human rotator cuff tendons with degenerative tears. Am J Sports Med 40 (2012): 1035-1045.

- Chen L, Liu JP, Tang KL, et al. Tendon-derived stem cells promote platelet-rich plasma healing in collagenase-induced rat Achilles tendinopathy. Cell Physiol Biochem 34 (2014): 2153-2168.

- Strnad J, Burke JR. IκB kinase inhibitors for treating autoimmune and inflammatory disorders: potential and challenges. Trends Pharmacol Sci 28 (2007): 142-148.

- Pochini AC, Antonioli E, Bucci DZ, et al. Analysis of cytokine profile and growth factors in platelet-rich plasma obtained by open systems and commercial columns. Einstein (Sao Paulo) 14 (2016): 391-397.

- Tognoloni A, Bartolini D, Pepe M, et al. Platelet-rich plasma increases antioxidant defenses of tenocytes via Nrf2 signal pathway. Int J Mol Sci 24 (2023).

- Tohidnezhad M, Varoga D, Wruck CJ, et al. Platelet-released growth factors can accelerate tenocyte proliferation and activate the antioxidant response element. Histochem Cell Biol 135 (2011): 453-460.

- Schnabel LV, Mohammed HO, Miller BJ, et al. Platelet-rich plasma (PRP) enhances anabolic gene expression patterns in flexor digitorum superficialis tendons. J Orthop Res 25 (2007): 230-240.

- Kajikawa Y, Morihara T, Sakamoto H, et al. Platelet-rich plasma enhances the initial mobilization of circulation-derived cells for tendon healing. J Cell Physiol 215 (2008): 837-845.

- Everts PA, Lana JF, Onishi K, et al. Angiogenesis and tissue repair depend on platelet dosing and bioformulation strategies following orthobiological platelet-rich plasma procedures: a narrative review. Biomedicines 11 (2023).

- Dohan Ehrenfest DM, Rasmusson L, Albrektsson T. Classification of platelet concentrates: from pure platelet-rich plasma (P-PRP) to leucocyte- and platelet-rich fibrin (L-PRF). Trends Biotechnol 27 (2009): 158-167.

- Yan R, Gu Y, Ran J, et al. Intratendon delivery of leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma improves healing compared with leukocyte-rich platelet-rich plasma in a rabbit Achilles tendinopathy model. Am J Sports Med 45 (2017): 1909-1920.

- Vetrano M, Castorina A, Vulpiani MC, et al. Platelet-rich plasma versus focused shock waves in the treatment of jumper’s knee in athletes. Am J Sports Med 41 (2013): 795-803.

- Fitzpatrick J, Bulsara M, Zheng MH. The effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma in the treatment of tendinopathy: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled clinical trials. Am J Sports Med 45 (2017): 226-233.

- Zhou Y, Zhang Y, Wu H, et al. The differential effects of leukocyte-containing and pure platelet-rich plasma (PRP) on tendon stem/progenitor cells — implications of PRP application for the clinical treatment of tendon injuries. Stem Cell Res Ther 6 (2015): 173.

- Zhao D, Han YH, Pan JK, et al. The clinical efficacy of leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma in arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 30 (2021): 918-928.

- Cheng PG, Yang KD, Huang LG, et al. Comparisons of cytokines, growth factors and clinical efficacy between platelet-rich plasma and autologous conditioned serum for knee osteoarthritis management. Biomolecules 13 (2023).

- von Wehren L, Pokorny H, Blanke F, et al. Injection with autologous conditioned serum has better clinical results than eccentric training for chronic Achilles tendinopathy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 27 (2019): 2744-2753.

- Damjanov N, Barac B, Colic J. The efficacy and safety of autologous conditioned serum (ACS) injections compared with betamethasone and placebo injections in the treatment of chronic shoulder joint pain due to supraspinatus tendinopathy: a prospective, randomized, double-blind, controlled study. Med Ultrason 20 (2018): 335-341.

- Coskun HS, Yurtbay A, Say F. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous conditioned serum in osteoarthritis of the knee: clinical results of a five-year retrospective study. Cureus 14 (2022): e24500.

- Frizziero A, Giannotti E, Oliva F, et al. Autologous conditioned serum for the treatment of osteoarthritis and other possible applications in musculoskeletal disorders. Br Med Bull 105 (2013): 169-184.

- Filardo G, Kon E, Di Matteo B, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for the treatment of patellar tendinopathy: clinical and imaging findings at medium-term follow-up. Int Orthop 37 (2013): 1583-1589.

- Andriolo L, Altamura SA, Reale D, et al. Nonsurgical treatments of patellar tendinopathy: multiple injections of platelet-rich plasma are a suitable option: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 47 (2019): 1001-1018.

- van der Heijden RA, Stewart Z, Moskwa R, et al. Platelet-rich plasma for patellar tendinopathy: a randomized controlled trial correlating clinical outcomes and quantitative imaging. Radiol Adv 1 (2024): umae017.

- Gosens T, Den Oudsten BL , Fievez E, et al. Pain and activity levels before and after platelet-rich plasma injection treatment of patellar tendinopathy: a prospective cohort study and the influence of previous treatments. Int Orthop 36 (2012): 1941-1946.

- Madhi MI, Yausep OE, Khamdan K, et al. The use of PRP in treatment of Achilles tendinopathy: a systematic review of literature. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 55 (2020): 320-326.

- Wang C, Fan H, Li Y, et al. Effectiveness of platelet-rich plasma injections for the treatment of acute Achilles tendon rupture: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore) 100 (2021): e27526.

- Zhang YJ, Xu SZ, Gu PC, et al. Is platelet-rich plasma injection effective for chronic Achilles tendinopathy? A meta-analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 476 (2018): 1633-1641.

- Kaux JF, Bouvard M, Lecut C, et al. Reflections about the optimization of the treatment of tendinopathies with PRP. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J 5 (2015): 1-4.

- Daniels EW, Cole D, Jacobs B, et al. Existing evidence on ultrasound-guided injections in sports medicine. Orthop J Sports Med 6 (2018): 2325967118756576.

- Fang WH, Chen XT, Vangsness CT Jr., et al. Ultrasound-guided knee injections are more accurate than blind injections: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 3 (2021): e1177-e1187.

- Hovland S, Amin V, Liu J, et al. Perioperative leukocyte-poor platelet-rich plasma associated with reduced risk of retear after arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Arthroscopy (2025).

- Creaney L, Wallace A, Curtis M, et al. Growth factor-based therapies provide additional benefit beyond physical therapy in resistant elbow tendinopathy: a prospective, single-blind, randomized trial of autologous blood injections versus platelet-rich plasma injections. Br J Sports Med 45 (2011): 966-971.

- Rossi LA, Brandariz R, Gorodischer T, et al. Subacromial injection of platelet-rich plasma provides greater improvement in pain and functional outcomes compared to corticosteroids at 1-year follow-up: a double-blinded randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 33 (2024): 2563-2571.

- von Wehren L, Blanke F, Todorov A, et al. The effect of subacromial injections of autologous conditioned plasma versus cortisone for the treatment of symptomatic partial rotator cuff tears. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 24 (2016): 3787-3792.

- Mi B, Liu G, Zhou W, et al. Platelet-rich plasma versus steroid on lateral epicondylitis: meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Phys Sportsmed 45 (2017): 97-104.

- Arirachakaran A, Sukthuayat A, Sisayanarane T, et al. Platelet-rich plasma versus autologous blood versus steroid injection in lateral epicondylitis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Orthop Traumatol 17 (2016): 101-112.

- Gupta PK, Charya A, Khanna V, et al. PRP versus steroids in a deadlock for efficacy: long-term stability versus short-term intensity — results from a randomized trial. Musculoskelet Surg 104 (2020): 285-294.

- Chahla J, Cinque ME, Piuzzi NS, et al. A call for standardization in platelet-rich plasma preparation protocols and composition reporting: a systematic review of the clinical orthopaedic literature. J Bone Joint Surg Am 99 (2017): 1769-1779.

- Rodriguez-Sanz J, Rodríguez-Rodríguez S, López-de-Celis C, et al. Biological and cellular effects of percutaneous electrolysis: a systematic review. Biomedicines 12 (2024).

- Abat F, Sánchez-Sánchez JL, Martín-Nogueras AM, et al. Randomized controlled trial comparing the effectiveness of the ultrasound-guided galvanic electrolysis technique (USGET) versus conventional electrophysiotherapeutic treatment on patellar tendinopathy. J Exp Orthop 3 (2016): 34.

- Abat F, Valles SL, Gelber PE, et al. Molecular repair mechanisms using the intratissue percutaneous electrolysis technique in patellar tendonitis. Rev Esp Cir Ortop Traumatol 58 (2014): 201-205.

- Yildizgoren MT, Mutlu Ekici SN, Ekici B, et al. Biochemical reactions and ultrasound insights in percutaneous needle electrolysis therapy. Interv Pain Med 4 (2025): 100593.

- Penin-Franch A, García-Vidal JA, Martínez CM, et al. Galvanic current activates the NLRP3 inflammasome to promote type I collagen production in tendon. Elife 11 (2022).

- Wang CJ, Wang FS, Yang KD, et al. Shock wave therapy induces neovascularization at the tendon-bone junction: a study in rabbits. J Orthop Res 21 (2003): 984-989.

- Wang CJ, Ko JY, Chan YS, et al. Extracorporeal shockwave for chronic patellar tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med 35 (2007): 972-978.

- Smith J, Sellon JL. Comparing PRP injections with ESWT for athletes with chronic patellar tendinopathy. Clin J Sport Med 24 (2014): 88-89.

- Tung WS, Daher M, Covarrubias O, et al. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy shows comparative results with other modalities for the management of plantar fasciitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Foot Ankle Surg 31 (2025): 283-290.

- Abat F, Gelber PE, Polidori F, et al. Clinical results after ultrasound-guided intratissue percutaneous electrolysis and eccentric exercise in the treatment of patellar tendinopathy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 23 (2015): 1046-1052.

- Abat F, De la Fuente C, Roby M, et al. Improvement responses in patellar tendinopathy patients treated with ultrasound-guided galvanic electrolysis technique: a 3-year follow-up study. J Exp Orthop 12 (2025): e70323.

- Calderon-Diez L, Sánchez-Sánchez JL, Belón-Pérez P, et al. Cadaveric and ultrasound validation of percutaneous electrolysis approach at the distal biceps tendon: a potential treatment for biceps tendinopathy. Diagnostics (Basel) 12 (2022).

- Gongora-Rodriguez J, Rodríguez-Huguet M, Rodríguez-Almagro D, et al. Percutaneous electrolysis, percutaneous peripheral nerve stimulation, and eccentric exercise for shoulder pain and functionality in supraspinatus tendinopathy: a single-blind randomized clinical trial. J Funct Morphol Kinesiol 10 (2025).

- Rodriguez-Huguet M, Góngora-Rodríguez J, Rodríguez-Huguet P, et al. Effectiveness of percutaneous electrolysis in supraspinatus tendinopathy: a single-blinded randomized controlled trial. J Clin Med 9 (2020).

- Ilia I, Miuta CC, Osser G, et al. Ultrasound-guided versus landmark-based extracorporeal shock wave therapy for calcific shoulder tendinopathy: an interventional clinical trial. Diagnostics (Basel) 15 (2025).

- De-la-Cruz-Torres B, Barrera-García-Martín I, Valera-Garrido F, et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle electrolysis in dancers with chronic soleus injury: a randomized clinical trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med 2020 (2020): 4156258.

- Ronzio OA, Soares Fernandes MDR, Froes Meyer P, et al. Effects of percutaneous microelectrolysis on pain, ROM and morning stiffness in patients with Achilles tendinopathy. European Journal of Physiotherapy 19 (2017).

- Valera-Garrido F, Minaya-Muñoz F, Medina-Mirapeix F, et al. Ultrasound-guided percutaneous needle electrolysis in chronic lateral epicondylitis: short-term and long-term results. Acupunct Med 32 (2014): 446-454.

- Ferreira MHL, Araujo GAS, De-La-Cruz-Torres B. Effectiveness of percutaneous needle electrolysis to reduce pain in tendinopathies: a systematic review with meta-analysis. J Sport Rehabil 33 (2024): 307-316.

- Pirri C, Manocchio N, Sorbino A, et al. Percutaneous electrolysis for musculoskeletal disorders management in rehabilitation settings: a systematic review. Healthcare (Basel) 13 (2025).

- Zhou Y, Wang JH. PRP treatment efficacy for tendinopathy: a review of basic science studies. Biomed Res Int 2016 (2016): 9103792.

- Garner AL, Torres AS, Klopman S, et al. Electrical stimulation of whole blood for growth factor release and potential clinical implications. Med Hypotheses 143 (2020): 110105.

- Wang X, Jia S, Cui J, et al. Effect of extracorporeal shock wave combined with autologous platelet-rich plasma injection on rotator cuff calcific tendinitis: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 25 (2024): 616.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 73.64%

Acceptance Rate: 73.64%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks