Management of Chronic Diseases through Oral Health and Nutrition Strategies

Valerie A Ubbes*, Abram Bailey

Department of Kinesiology, Nutrition, and Health, College of Education, Health, and Society, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056, USA.

*Corresponding Author: Valerie A Ubbes, Department of Kinesiology, Nutrition, and Health, College of Education, Health, and Society, Miami University, Oxford, OH 45056, USA.

Received: 16 January 2026; Accepted: 24 January 2026; Published: 30 January 2026

Article Information

Citation: Valerie A Ubbes, Abram Bailey. Management of Chronic Diseases through Oral Health and Nutrition Strategies. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research. 10 (2026): 49-59.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

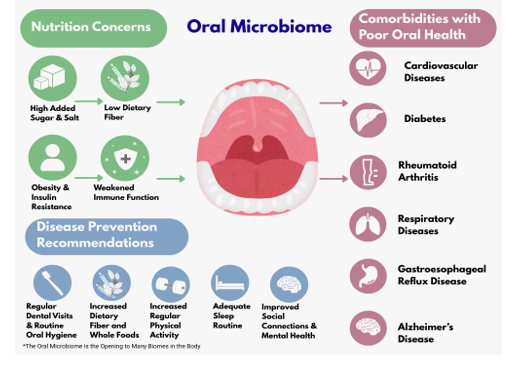

The relationship between nutrition and oral health remains a vital component of overall health. According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics, oral health and nutrition have a synergistic multidirectional relationship in human health. The World Health Organization promotes a global oral health action plan to reduce sugar consumption in 50 percent of countries by 2030, with the aim of reducing overweight, obesity, chronic systemic infection, and dental caries. The intersection between oral health and noncommunicable chronic diseases is important because the oral cavity has a profound impact on systemic health. With the National Institute of Health’s release of the 2021 book, Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges, there is an ongoing need for narrative reviews to describe research connections between oral health and the prevention of cardiovascular disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, respiratory disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Because the microbiomes of the oral cavity, gut, and brain share access to food and nutrients, a summary of microbiota activity can be helpful for professionals when discussing dental caries and periodontitis with their patients. The purpose of this paper is twofold: 1) to review current research highlighting the relationship between chronic diseases and oral health, and 2) to outline practical oral health, nutrition, and lifestyle strategies for dentists and dietitians so they can talk about chronic disease prevention with their patients and clients.

Keywords

Chronic disease prevention, Oral health, Nutrition strategies, Dentists, dietitians, Cardiovascular disease, Diabetes, Rheumatoid arthritis, Respiratory disease, Gastroesophageal reflux disease, Alzheimer’s disease

Article Details

Introduction

The relationship between nutrition and oral health remains a vital component of overall health. According to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics [1], oral health and nutrition have a synergistic multidirectional relationship in human health. The World Health Organization promotes a global oral health action plan to reduce sugar consumption in 50 percent of countries by 2030 in order to reduce overweight, obesity, chronic systemic infection, and dental caries [2]. The intersection between oral health and noncommunicable chronic diseases is important because the oral cavity has a profound impact on systemic health [3]. With the National Institute of Health’s release of the 2021 book, Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges, connections between oral health and nutrition continued to be promoted [4]. However, there remains an ongoing need for research to focus on specific disease conditions and mechanisms for describing the role of the oral cavity in general health status. Clinical research and systematic reviews are needed to reduce the burden of chronic noncommunicable diseases and dental diseases. An estimated 80% of chronic diseases and premature death can be prevented through nutrition and lifestyle habits [5]. Although national and international public health initiatives provide research direction, there are few practical interventions to support the general public. For example, the US Department of Health and Human Services continues to collect progress data on oral health conditions and nutrition indicators for human health, but only one of the national Healthy People 2030 objectives, Oral Health-01, minimally mentions the interface between the two in a summary statement about reducing lifetime tooth decay among children and adolescents [6]. Specifically, the purpose of this paper is twofold: 1) to summarize the current research highlighting the relationship between chronic diseases and oral health, and 2) to outline oral health, nutrition, and lifestyle strategies for dentists and dietitians so they can help to reduce chronic diseases and enhance the immune function of their patients and clients. Our hopeful aim is to support and accelerate interdisciplinary progress between health professionals and the general public. We begin with a brief overview of the oral microbiome, then move into specific summaries of chronic diseases that have etiologies in oral health and nutrition.

Multiple microorganisms (e.g., viruses, mycoplasma, bacteria, fungi, Archaea, and protozoa) live in the mouth [7]. Imbalances between microbes and pathogens in the oral microbiota predispose the individual to periodontal diseases, including changes in the oral-gut axis, where inflammatory mediators can compromise systemic health. Recent research has shown that oral microbes can travel through the digestive tract to the gut [8], and establish symbiotic and dysbiotic responses from the human organism [9]. Indeed, lifestyle choices and environmental factors influence the intricate balance and diversity of microorganisms within our oral ecosystem [9] and require an ecological perspective to look at how the health of the mouth affects the synergy of other microbiomes in the body and vice versa. Oral microbes can live in the oral cavity in symbiotic healthy relationships to one another, especially when there are adequate high fiber diets and lower carbohydrate intakes of fructose, sucrose, and maltose, to name a few. From a dysbiotic perspective, diets high in sugar can lower the pH of the oral ecosystem and shift more acid-producing microorganisms to increase conditions for dental caries, periodontitis, and oral candidiasis [10]. The early onset of diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, and Alzheimer’s disease is being studied for a higher abundance of the periodontal pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis, with a need to manage biofilm control through daily oral hygiene practices to further reduce inflammatory responses and subsequent risks of systemic chronic diseases [7,11,12].

Research on periodontitis is especially important to understand as a backdrop to inflammatory conditions that contribute to risks for a variety of chronic diseases. Periodontitis is a more serious form of inflammation where the gums can pull away from the teeth, resulting in them loosening or falling out. In the earliest stages of gum disease, the gums become swollen and red, which is called gingivitis. This condition is the most common form of periodontal disease due to the plaque or bacterial biofilms that become attached to the tooth surfaces. Without treatment, gingivitis can progress to periodontitis. Hence, individuals need dental checkups every 6 months to reduce accumulated biofilms, daily oral hygiene that includes brushing twice a day using fluoride-containing toothpastes at 1000 to 1500 parts per million [13], rinsing the mouth with lots of water, daily flossing, and eating diets high in fresh foods, fiber, vitamins, and minerals. The use of oscillation-type toothbrushes is encouraged over manual toothbrushes to keep plaque reduced [14]. The next part of this narrative review will focus on how oral health is associated with heart disease, diabetes, rheumatoid arthritis, respiratory disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease, and Alzheimer’s disease. Chronic disease prevention informed by oral hygiene and nutrition strategies will be included in many sections based on the available knowledge base for that disease. See Figure 1 for this relationship. Figure 2 shows a summary of the diseases that will be discussed.

Heart Disease and Oral Health

A strong association exists between cardiovascular disease and oral health diseases, e.g., atherosclerosis and periodontitis. When microorganisms are released into the bloodstream as a result of compromised periodontal tissues, systemic inflammation increases [7]. When lipids and cholesterol accumulate to form atherosclerotic plaques within the artery walls, there is evidence that the pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis, invades the cardiovascular cells to induce systemic inflammation [15] and degrades the endothelial barrier of the vessel walls, causing vascular permeability [16]. The progression of atherosclerosis is accelerated when platelets aggregate and release proteins called proinflammatory cytokines, leading to vascular dysfunction [17-19]. In an inflamed oral cavity, the release of chemical messengers in the immune system, known as cytokines TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-17, impairs endothelial function of the blood vessels, leading to higher pressure or hypertension. Current evidence has shown that the endothelial lining of vessels improves when periodontal treatments reduce the biofilm on inflamed gums. Associated reductions in C-reactive protein levels and blood pressure have been found after periodontal gum treatments [20,21]. The nitrate cycle, beginning with the tongue and saliva, is an additional process that serves a beneficial role in regulating blood pressure through vasodilation [22,23].

Nutrition Strategies

During the aging process, adults are more susceptible to infection-driven periodontitis and loss of gum tissue [24]. To fight age-associated bone loss in periodontitis, interventions to reduce gum inflammation should include Mediterranean-style diets, which are characterized by olive oil as the main fat source, a moderate dairy intake, high plant food intake, and limited fish and poultry consumption [24]. Olive oil and peanut oil are rich in oleic acid, which reduces inflammation and provides an inhibitory effect on insulin production, respectively [25]. Olive oil also prevents harmful lipid intermediates from accumulating in blood vessels, which is critical in heart disease prevention. In contrast, a Western-style diet is high in saturated fatty acids, specifically palmitic acid, which is known to be associated with periodontal disease and heart disease [26]. Palmitic acid, found in processed meat, red meat, butter, eggs, refined grains, and high-fat dairy products, has been linked to disrupted lipid and bone metabolism [27]. More recent research has shown that gingival fibroblasts will indirectly modulate the inflammatory response and the integrity of oral bones [24]. Vitamin D directly affects bone metabolism and has anti-inflammatory properties. Vitamin D levels play an important role in bone growth and tooth formation. Deficiency in Vitamin D or magnesium is associated with skeletal deformities and cardiovascular diseases [28], and the dysregulation of Vitamin D is linked to periodontal disease. Supplementation of Vitamin D is important in converting diseased tissue damage into healthy tissue when diagnosed with gingivitis and/or periodontitis. Good food sources of Vitamin D include salmon, herring, sardines, canned tuna, eggs, mushrooms, and Vitamin D-fortified foods, e.g., cow’s milk, soy milk, and orange juice. As a hormone, Vitamin D is necessary for the absorption of calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus in the intestines [28]. Maternal Vitamin D deficiency increases the DMFT (decayed, missing, filled, primary teeth) score for children aged 12 to 35 months [29]. Therefore, nutritional strategies for cardiovascular and tooth health must include Vitamin D, along with proper balances of calcium, magnesium, and phosphorus. Whereas magnesium is required for the synthesis and metabolism of Vitamin D, Vitamin D is important in regulating calcium and phosphorus [28].

Diabetes and Oral Health

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic disease characterized by high blood sugar (hyperglycemia), low insulin levels, and an often irreversible condition leading to many other health declines [3]. Diabetes causes a lack of optimal cell function through the decrease of glucose entering the cell, which causes a worsened response in healing and an increase in factors that harm the body. This is often the result of beta cell dysfunction, where the cells in the pancreas responsible for producing and releasing insulin lack critical function [30]. Because insulin is responsible for allowing glucose into cells, the lack of insulin or low production causes a higher concentration of glucose in the blood, resulting in less energetic cells. Beta cell dysfunction can be caused by various factors, but it has a strong tie to genetics, glucolipotoxicity, and proinflammatory cytokines that cause oxidative stress on the beta cells [30]. Insulin resistance and target cell dysfunction are also critical factors for hyperglycemia in diabetes. Commonly associated with obesity and inflammation, insulin resistance occurs when insulin is being secreted adequately; however, when there are high levels of fatty acids and oxidative stress, muscle and organ cells become damaged, causing insulin dysfunction for glucose-desensitized organs and cells [30]. Another condition called hyperinsulinemia is a form of insulin resistance and early-stage type 2 diabetes. Sohn et al. state that “hyperinsulinemia also drives adipose tissue dysfunction and lipotoxicity, amplifying systemic inflammation and elevating circulating cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α, which may affect periodontal tissues” [31]. Harmful factors are amplified by the direct damage that poor blood sugar management can have on blood vessels, potentially causing cardiovascular issues and worsened circulation of oxygen-rich blood. Hyperglycemia is responsible for many proinflammatory responses that release harmful cytokines, causing damage to vital organs like the kidneys, liver, eyes, and heart, including the nerves and blood vessels [32]. Because oxygen is required for proper metabolic processes, such as maintaining an energy supply and keeping tissue alive, a lack of oxygen can lead to fatal results.

In addition to the many known cytokine-contributed comorbidities of diabetes– cardiovascular, kidney, liver, and eye diseases– is a high correlation to oral health issues such as, “periodontal diseases, apical periodontitis (AP), head and neck cancer (HNC), salivary gland diseases, dental caries, and root fracture, while also impeding the healing process of extraction sites” [3]. Many of these oral health diseases are associated with the increased presence of inflammation, a decrease in the body’s ability to heal itself, and a microbiome that is easily harmed by sugar. For example, periodontitis has been previously associated with P. gingivalis, Treponema denticola, and Tannerella forsythia oral anaerobic bacteria [33]. However, recent research shows that the anaerobic oral bacteria may not directly cause periodontitis, as mice in a germ-free environment with the bacteria showed no sign of periodontitis [33]. Instead, a new model shows that a pathogen may colonize the oral microbiome, destroying the biofilm and healthy bacteria that work to break down food and protect the teeth and gums to maintain oral health [33]. This is especially dangerous and prevalent in diabetes, as the body does not respond to pathogens as efficiently, and there tend to already be harmful inflammatory cytokines that can work together with pathogens to cause additional harm. So when a pathogen presents itself, the weakened immune systems of diabetics tend not to fight off infection, inflammation, and disruption to the oral microbiome, thus contributing to the high rate of all the oral health diseases mentioned. Additionally, low blood sugar can be a major oral health issue as the treatment is often a high amount of sugar or glucose, which feeds bacteria, including “mutans streptococci and lactobacilli as well as aciduric strains of non-mutans streptococci, Actinomyces, bifidobacteria, and yeasts” [34]. These bacteria then release acid, which is highly abrasive to the enamel and can also harm helpful bacteria, causing dental caries and other oral health issues [35].

Unfortunately, the chronic diseases associated with diabetes are often bidirectional, presenting an association of additional chronic disease development when only one is present initially [36]. This is often the result of long-term mismanagement of glucose levels and disruption of the oral microbiome, which subsequently affects the nervous, gut, blood, and brain microbiomes through the transfer of bacteria and pathogens throughout the body and an increase in inflammatory markers [36].

Nutrition Strategies

Due to the direct relationship that lifestyle and nutrition have on diabetes management and disease progression, treatment must include glucose monitoring, food preparation and diet planning, and regular goals for optimizing overall health. The inclusion of dietary fiber with every meal is a good starting strategy for regulating blood sugar, improving bowel function, and reducing the risk of bowel cancers and disease [37]. While soluble fiber has been shown to have positive effects on glucose regulation, insoluble fiber has been shown to improve gut behavior and bowel function [37]. Soluble fiber can lower cholesterol and lipid profiles through improved epithelial function [37]. Slowing down digestion allows people to feel satiated sooner and for a longer period of time. Additionally, increased insulin sensitivity helps the effects of insulin to work more optimally for adequate glucose uptake and proper energization. Insulin supplementation through medication may still be necessary for diabetics despite nutritional methods. While insulin is a critical and immediate treatment for glucose levels, nutrition and dietary modifications are best for long-term chronic disease management. Diets that have a higher amount of dietary fiber, lower cholesterol levels, lower sugar consumption, and healthy fat consumption through nutritious whole foods have been shown to significantly improve the health of diabetics.

Of the many dietary choices, the Mediterranean Diet is effective for diabetes management, improving many physiological processes by promoting whole foods, lowering sugar consumption, higher dietary fiber, and improving cholesterol and lipid levels. The Mediterranean Diet commonly emphasizes the consumption of in-season fruits, vegetables, whole grains, healthy fats like olive oil, nuts, seeds, reduced dairy, and lean meats [38]. Consumption of this diet improves long-term and short-term diabetes management through the immediate positive effects fiber has on glucose management, in addition to improvements in cholesterol, lipids, weight, proinflammatory cytokines, and more [38]. This is significant as much of the Western diet has had opposite effects on the body by increasing inflammation, chronic disease, oxidative stress, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and health declines through metabolic issues [26]. So, by changing one’s diet, the diabetes symptoms and disease progression may be improved to a better baseline state. This diet is best accompanied by lifestyle modification, such as regular exercise, good sleep, social connections, and good hygiene.

Oral Health Strategies

One of the most important hygiene modifications includes careful attention to oral hygiene. Because oral health has been shown to have significant links to altering microbiomes throughout the body, it is especially important for diabetics to follow the current research. With an already suppressed immune system, pathogens and other disease-causing agents can easily cause oral health issues, as explained above. Current recommendations include brushing teeth with fluoridated toothpaste at least 2 times daily, flossing at least once per day, and, if recommended by a dentist, rinsing out the mouth with a fluoridated and antimicrobial mouthwash after meals [39]. Diabetics may require more frequent dental visits, often every 3 to 6 months for oral cleanings to ensure proper dentition, gum, and teeth health [39]. Early action helps to prevent the onset of diseases such as periodontitis. In conclusion, habitual oral hygiene ensures a healthy oral microbiome so that disruption of other microbiomes throughout the body does not occur.

Rheumatoid Arthritis and Oral Health

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic inflammatory stiffening that affects the synovial membranes of small and large joints. Rheumatoid arthritis is the world’s most common systemic autoimmune disease, affecting 1 percent of the world’s population [11]. The pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis, is implicated in the production of citrullinated proteins, which have been modified from their original form. In rheumatoid arthritis, the immune system creates antibodies that can mistakenly target these citrullinated proteins, leading to inflammation. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis will have a 2.538 higher risk for arthritis in the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) than individuals without rheumatoid arthritis [40]. Patients with rheumatoid arthritis also have greater incidence of dry mouth [41], greater dental plaque due to elevated Staphylococcus mutans counts [41], and a higher frequency and severity of dental caries [42].

Nutrition Strategies

The microbiome of the oral cavity transforms nutrients from food to act as a barrier against pathogens entering the body [9]. If the oral microbiome has a disruption or imbalance known as dysbiosis, an inflammatory response occurs, which further compromises the immune system. Neutrophils are involved in the early immune response, combating infection by releasing antimicrobial substances and phagocytosing bacteria [7]. Neutrophils also release free radicals and enzymes that lead to tissue damage and further inflammation [7]. Two common oral dysbioses are caries and periodontitis. A diet high in sugar can lead to dysbiosis; high sugar diets cause the microbiome to shift into low pH, increasing acid-producing microorganisms that lead to dental caries. Furthermore, if the microbiome shifts into an inflammatory stage, anaerobic microorganisms contribute to periodontitis [43] and a cascade of other processes. Dendritic cells activate several subtypes of T cells, which promote the inflammatory response [7]. Macrophages further the inflammatory response and tissue destruction by releasing proinflammatory cytokines (such as tumor necrosis factor-α, [TNF-α], interleukin-1 [IL-1β], interleukin-6 [IL-6]), leading to the formation of rheumatoid arthritis [44]. Some macrophages also release beneficial anti-inflammatory cytokines (such as IL-10) to promote tissue repair [7].

In recent years, studies on rheumatoid arthritis have implicated red meat and salt as harmful to the gut microbiota and body composition [45]. The 2022 American College of Rheumatology recommends that the Mediterranean diet be consumed by patients who have rheumatoid arthritis [46]. Patients should have a limited intake of sugary desserts, saturated fats, and red processed meats. Patients should have high dietary adherence to fruits, vegetables, nuts, legumes, whole grains, olive oil, and seafood, because these foods are associated with a 16% reduction in risk for developing rheumatoid arthritis [47]. To suppress the inflammatory process in rheumatoid arthritis, adequate dietary protein, omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids, and antioxidants via vitamins and minerals are suggested [48]. In a systematic review investigating dietary effects on rheumatoid arthritis [49], several studies highlighted the anti-inflammatory properties of vitamin D supplements, flaxseeds, pomegranate extract, ginger, cranberry juice, and fish oil. The phenolic substances of fruits and vegetables can reduce oxidative stress. Specifically, polyphenols can neutralize free radicals by giving them a hydrogen atom to strengthen the antioxidant defense system [50]. Other research summaries on the independent consumption of cinnamon, Vitamin B6, zinc, and fiber have shown positive results for reducing joint pain and inflammation [44]. A diet rich in fruits containing proteolytic enzymes such as papaya, mango, pineapple, including turmeric, black pepper, green tea, and legumes, is also an anti-inflammatory asset to the diet [51]. More robust evidence-based dietary recommendations for patients with rheumatoid arthritis are needed since individual responses to the Mediterranean diet are variable [44].

Oral Health Strategies

Periodontal inflammation represents a chronic burden of inflammatory cytokines on the body. For example, the oral bacteria of Porphyromonas gingivalis and Prevotella intermedia have been found in synovial fluid of the joints [52]. Since rheumatoid arthritis and periodontitis share the same imbalance of cytokines [11] and periodontitis patients have a 69% greater risk of developing rheumatoid arthritis [53], patients need to be habitual in their brushing, flossing, and rinsing practices for reducing gum inflammation in their mouth. Brushing of the tongue has also shown statistically significant reductions in plaque levels after ten days and 21 days in a single blind, stratified comparison of three parallel groups of children who performed tongue brushing along with tooth brushing or performed only tooth brushing twice daily under professional supervision [54].

Respiratory Diseases and Oral Health

The upper respiratory tract lies just below the oral cavity, where the teeth, gingival sulcus, tongue, inner cheeks, attached gingiva, and palates are located. The oral cavity contains the second most diverse microbiome in the body, with over 700 species of bacteria, viruses, fungi, and protozoa [55]. With such a diversity of microbes, it is reasonable to assume that pathogens from the oral cavity can migrate down into the upper respiratory tract to cause infections such as pneumonia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, lung cancer, and asthma [56].

The interactions of lung diseases and oral health diseases establish dysbiosis in the lung-oral microbiome [57]. Patients with healthy oral cavities have less risk of lung diseases compared to patients who have infectious caries, gingivitis, and/or periodontitis [56]. Poor oral hygiene of the oral cavity increases the number of anaerobic microbes in the lungs, including Porphyromonas gingivalis, Bacteroides grucilus, Eikenella corrodens, Fusobacterium nucleutum, Fusobacterium necrophorum, Peptostreptococcus, Clostridium, and Actinomyces [56]. Poor oral hygiene of the elderly is associated with an increased risk of pneumonia caused by Streptococcus pneumonia and Hemophilus influenzae in community cases and Staphylococcus aureus in hospital cases [56]. Wearing dentures during sleep causes oral microbiome colonization with an increased risk of aspiration of pathogens into the lungs, leading to pneumonia [58].

The epiglottis is responsible for stopping most saliva from entering the lower respiratory tract [59]. However, under unique circumstances, oral bacteria can migrate from the mouth to the respiratory tract and colonize the lungs, triggering an immune and inflammatory response [3]. Patients with poor oral health tend to have various lung diseases, such as asthma, chronic obstructive lung disease, pulmonary fibrosis, and pneumonia [3]. Patients with asthma may have an elevated risk of periodontitis [60].

Nutrition Strategies

Zinc is an essential trace element that is present naturally in the mouth in plaque, saliva, and enamel. Zinc is also added to oral health products to control plaque, reduce bad breath, and stop the formation of calculus [61]. Zinc is important for bone growth, the production of hormones such as insulin and testosterone, sperm production, and fetal development. Because zinc is necessary for the immune system to function properly and the healing of wounds, people with respiratory diseases should meet the recommended dietary allowance (RDA) for zinc, which is 11 milligrams per day for adult men and 8 milligrams per day for adult women [62]. Food sources of zinc include oysters, beef, breakfast cereals, oats, pumpkin seeds, pork, turkey, cheese, and cashews [62].

Oral Health Strategies

Inflammatory cytokines induced by periodontitis play a role in the pathogenesis of pneumonia [63]. Research has shown that P. gingivalis induces pneumonia in mice with periodontitis, showing cytokines in peripheral blood and lung tissue [64]. Therefore, the same measures for reducing periodontitis of the mouth may be helpful for preventing pneumonia in the lungs. Since periodontitis is an inflammation of the gums and the bone that supports the teeth, the first step is to determine if poor oral hygiene is the cause. However, some people can be prone to gum disease even with proper brushing and flossing. Symptoms may include reddish or purplish gums, bleeding, soreness, bad breath, pain when chewing, gum recession, loose teeth, and a change in the way the teeth fit together [65]. In some people, genes play a role in gum disease by changing the way that their immune system responds to bacteria. If family members have gum disease, it is more likely to occur in the next generations as well. Some of the ways to lower the risk for periodontal disease include brushing teeth two to three times every day, flossing between the teeth daily, using an antibacterial mouthwash, visiting the dentist for regular cleanings and exams, and avoiding smoking and other tobacco use [65]. The latter strategy of avoiding the use of tobacco will be key to also reducing conditions for asthma (and pneumonia), in which there is swelling in the lining of the lung airways and a secretion of mucus. Using an air indoor filtration system to remove mold, pollen, dust mites, and other allergens, like tobacco, can help to reduce inflammation in the oral microbiome and lungs.

Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease and Oral Health

Gastroesophageal reflux disease, or GERD, is a disorder of the upper gastrointestinal system that causes acid from the stomach to backflow to the esophagus and can even lead to frequent regurgitation. Due to the commonality of this disease and prevalence throughout the United States population, about 9.3 billion dollars have been spent on the diagnosis, consultation, and treatment of GERD [66]. There are various causes of GERD, most of which include a weakening or disorder of the lower esophageal sphincter [67]. The lower esophageal sphincter allows food in for absorption, digestion, and aims to keep acid from entering back into the esophagus. When weakening and disorders occur in the lower esophageal sphincter, acid from the stomach with a pH around 1.5 [68] can flow back up to the esophagus and even into the oral cavity. This poses a health issue because the esophagus tends to function best at a pH level of around 7 [69], and the oral cavity prefers a pH of 6.2-7.6 [70]. When the pH becomes too acidic, the mucosal lining in the esophagus can start to break down, causing a cycle of more issues from GERD, such as Barrett's esophagus, cancer, generalized pain, and more [66]. Additionally, when acid gets into the mouth, larger issues can occur, including disruption of the oral microbiome, abrasion of the enamel and gums, and overall irritation and inflammation of the passage from the mouth to the stomach.

Ultimately, GERD is a large contributor to dental caries, gum disease, and inflammation of the throat and mouth. One study found that 81% of patients in a 105-patient sample with GERD complained of oral cavity issues such as dry mouth, acidic or bitter taste, burning sensation, odor, and throat discomfort [71]. Because GERD is such a large contributor to oral health issues and comorbidities, dentists must be trained to combat these symptoms in collaboration with other professionals, such as dietitians, therapists, and physicians, who may be able to better tackle the root of the issue. This collaborative treatment is especially important in GERD because it is often a secondary disease that presents after other diseases such as diabetes mellitus, anxiety, depression, cardiovascular disease, cerebrovascular disease, Parkinson’s disease, and pulmonary disease [66]. These diseases are often associated with gastric dysmotility and delayed gastric emptying, which increases the pressure in the stomach and causes a backload of acid into the esophagus to relieve the high-pressure gradient in the stomach [66,72]. There are many physiologic processes for acid regulation such as sphincters that prevent acid backflow, however, bacteria in the gut microbiome also help maintain homeostatic acid conditions by increasing or lowering acid levels. Although controversial, many studies have shown that Helicobacter pylori, especially positive strains of CagA H. pylori, have been shown to improve GERD symptoms by lowering acid levels, despite increasing inflammation and potential risk for other diseases [66]. On the other hand, some bacteria cause a great level of harm when there are imbalances in the homeostatic conditions of the oral cavity and upper gastrointestinal microbiomes. Similar to Helicobacter pylori, other prominent bacteria can cause dysbiosis as a response to certain diseases, medications, and external conditions.

Nutrition Strategies

Due to the high influx of acid, greater pressure in the stomach, and alteration of pH in the esophagus and oral cavity, multiple nutritional and lifestyle strategies for GERD can make significant improvements. Current recommendations include the reduction of caffeine, alcohol, smoking, spicy foods, fried foods, and other triggers that seem to cause negative symptoms in each individual [73]. Additionally, by eating more frequently with smaller meals, less pressure will be put on the stomach, causing less backflow of acid and food through the lower esophageal sphincter [73]. One significantly researched technique includes raising the head of the bed while sleeping [73]. When dysmotility occurs, the esophagus is less efficient at processing food from the mouth into the stomach for digestion. By using gravity and raising the head of one’s bed while sleeping, the reflux of acid can be reduced, thereby increasing sleep quality and reducing irritation. Some dietary recommendations for decreasing acid and improving GERD include eating higher amounts of non-acidic fruits and vegetables to increase dietary fiber, lean meats, and healthier fats such as olive oil [73]. These dietary options have shown significant improvements in the overall acidic state of the esophagus, motility, and digestive functions. Some diets that promote high fiber, moderate fats, and less acidic foods include the anti-reflux diet and the Mediterranean diet. Recent studies have shown that GERD symptoms have improved significantly using a wholly dietary approach, showing that proton pump inhibitors (medication specifically used for GERD and acid reduction) are not significantly more effective in GERD treatment [74]. Additionally, anti-reflux diets and the Mediterranean diet have been shown to have similar efficacy in GERD treatment [74]. Overall, proton pump inhibitors or anti-reflux medications could show significant, short-term improvements in digestive function. However, long-term use may cause more harm and disruption to the microbiome and larger digestive tract. Dietary improvements, such as following a low-acid, anti-reflux, Mediterranean diet, can help repair microbiome function, reduce GERD symptoms, and improve critical digestive functions.

Oral Health Strategies

Due to the abrasive effects acid has on the enamel and gums, it is critical to ensure that the teeth and gums have enough protection to combat the highly acidic environment. If left untreated, the acid can have significant issues, causing tooth fracture, dental caries, loss of tooth substance, hypersensitivity, and impairment [75]. However, significant improvements can be made using remineralization techniques and acid management through dietary changes and medication. To combat the acid levels, dentists recommend washing out the mouth with water, which helps remove the acid; sodium bicarbonate, which neutralizes remaining acid; and fluoride mouthwash, which helps in remineralization and protection of the oral cavity if used directly after an acid event [76]. Additionally, GERD patients may require more dental visits for the application of fluoride varnish, prescription of fluoride toothpaste, and education on remineralization techniques such as application of amorphous calcium phosphate to the teeth [76]. Dentists may also fill exposed teeth with resin, make a nightguard to reduce grinding of teeth, and perform restorative procedures [76]. Overall, dentists are first responders for various diseases that have systemic damage to the whole body, including the oral cavity. Through careful attention and keen educational practices, dentists can significantly improve patients’ lives by combating oral damage, referring patients to appropriate resources, and making lifestyle recommendations that can systematically improve the oral cavity of their patients and reduce disease progression.

Alzheimer's Disease and Oral Health

Alzheimer’s disease is a degenerative brain disorder caused by irreversible neuronal damage. The brain changes lead to cognitive decline, memory loss, and eventually complete loss of speech and mobility [7]. The oral-brain axis has been implicated in the progression of Alzheimer’s Disease [77]. One theory proposes that inflammation and specific oral pathogens, such as Porphyromonas gingivalis, may contribute to the progression of Alzheimer’s disease [9]. The translocation of P. gingivalis can lead to increased citrullination of host proteins, which can cause an autoimmune inflammatory response that may contribute to amyloid beta plaques and tau tangles [78]. In an umbrella review investigating the current knowledge of highly prevalent dental conditions and chronic disease, Seitz and colleagues showed the relationship of periodontitis to dementia and tooth loss to dementia [79]. Because separate groups of health care professionals treat patients with these diseases, intersectoral care is important so that the “dentist and general practitioner are sufficiently aware of existing correlations between dental conditions and chronic systemic diseases and how these correlations may influence treatments” [79](p. 8).

Nutrition Strategies

Nutrition strategies are necessary for benefiting patients with cognitive changes leading to memory decline and agitation. Consuming fruits, vegetables, and grains rich in antioxidant nutrients (e.g., Vitamins A, C, and E) is important in maintaining periodontal health [80]. Vitamin D-rich foods like salmon and sardines increase the mineral absorption of calcium and phosphorus, which helps to protect tooth enamel while preventing caries and unnecessary tooth loss. The degeneration of brain tissue can potentially be slowed by providing optimal conditions for body function through the consumption of lean meats, whole grains, fruits, vegetables, and a decreased intake of foods that are too high in saturated and trans fats.

The MIND diet, a hybrid between the DASH and Mediterranean diets, has been shown to decrease the rate of neurocognitive decline at an estimated greater rate than the DASH or Mediterranean diets alone [81]. Although the aim of the MIND diet (The Mediterranean-DASH Diet Intervention for Neurodegenerative Delay) is on brain health, the Mediterranean diet and the DASH diet (Dietary Approach to Stop Hypertension) also highlight plant-based foods and limit animal and high saturated fat foods. Both the DASH and Mediterranean diets have been shown to protect cardiovascular function, which in turn preserves neurological health [82]. By combining the best aspects of each diet through guidelines of whole and healthy food and the emphasis on decreased intake of unhealthy foods that are high in saturated and trans fat, the MIND diet provides an easy-to-follow plan for people with Alzheimer’s disease [82]. Specifically, some unhealthy foods to limit include: “less than 5 servings a week of pastries and sweets, less than 4 servings a week of red meat, less than one serving a week of cheese and fried foods, and less than 1 tablespoon a day of butter/stick margarine” [82]. Overall, the MIND diet helps increase intake of critical vitamins and minerals for neurocognitive preservation and optimal function.

Oral Health Strategies

Due to the high association Alzheimer’s disease has with oral health disease, more frequent and consistent dental cleanings and checkups are necessary. In addition to visiting a dentist at least twice per year, people with Alzheimer’s must have the care and capability to brush their teeth at least twice daily, and floss at least once per day. Because of brain degeneration, “simple” tasks like brushing one’s teeth are often overlooked, especially in hospitals and nursing homes. However, an emphasis on proper daily care can significantly reduce neurocognitive decline by ensuring the health of the oral microbiome to prevent systemic disruptions.

Lee and colleagues reported that untreated periodontitis patients had a significantly higher risk of dementia compared to those who received dental preventive treatments [83]. Periodontitis is the most prevalent bone disease in humans, affecting 40 to 90 percent of the global population, and if untreated, periodontitis can lead to tooth loss in adults [84]. Tooth loss leads to many dysbiotic consequences in the oral cavity, such as a change in diet to compensate for the loss of optimal mechanical digestion and an increase in inflammatory factors in the area of the tooth loss, which creates a vulnerable area in which harmful bacteria can grow [85].

Conclusion

The need for educating people on the role of oral health as a determinant of overall health is more possible than ever before. With growing research on the human holobiont as a host organism with all its associated microorganisms, specific effects on and within different body systems are becoming clearer. The oral microbiome serves as the entrance to all other body systems. A lack of care and attention to oral health can disturb the oral microbiome, which can then alter other microbiomes within the body. There is an increasing need for dental, medical, and dietetic collaboration when supporting patients in the management of their chronic disease. As described in this narrative review, disease interactions and prevention are possible with awareness of pathogens to reduce and regulate them through diet and improved oral health hygiene. By encouraging patients to practice enhanced nutrition and oral health strategies each day, health professionals can help boost immune function against specific pathogens to promote health and prevent disease.

Conflict of Interest: None

Funding Source: None

Clinical Trial Number: Not applicable

Human Ethics and Consent to Participate: Not applicable

References

- Touger-Decker R, Mobley C. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: Oral Health and Nutrition. J Acad Nutr Diet. 113 (2013): 693–701.

- World Health Organization. WHO Technical Information Note: Sugars and Dental Caries. World Health Organization, Geneva (2025).

- Fu D, Shu X, Zhou G, et al. Connection between oral health and chronic diseases. MedCom. 6 (2025): e70052.

- National Institutes of Health. Oral Health in America: Advances and Challenges. US Dept of Health and Human Services, Bethesda (2021).

- McGinnis JM, Foege WH. Actual causes of death in the United States. JAMA. 270 (1993): 2207–2212.

- S. Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2030: Oral Conditions Objectives. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion (2025).

- Zeng Y, Lin D, Chen A, et al. Periodontal treatment to improve general health and manage systemic diseases. In: Deng D, Do T, Dame-Teixeira N, eds. Oral Microbiome. Springer Nature Switzerland (2025): 245–260.

- Colombo APV, Lourenço TGB, de Oliveira AM, et al. Link between oral and gut microbiomes: The oral–gut axis. In: Deng D, Do T, Dame-Teixeira N, eds. Oral Microbiome. Springer Nature Switzerland (2025): 71–87.

- Dame-Teixeira N, Deng D, Do T, et al. The oral microbiome and us. In: Oral Microbiome. Springer Nature Switzerland (2025): 3–9.

- He J, Cheng L. The oral microbiome: A key determinant of oral health. In: Deng D, Do T, Dame-Teixeira N, eds. Oral Microbiome. Springer Nature Switzerland (2025): 133–149.

- Inchingolo F, Inchingolo AM, Avantario P, et al. Effects of periodontal treatment on rheumatoid arthritis and antirheumatic drugs on periodontitis. Int J Mol Sci. 24 (2023).

- Simpson TC, Clarkson JE, Worthington HV, et al. Treatment of periodontitis for glycaemic control in people with diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4 (2022): CD004714.

- Arany PR, Charles-Ayinde M, Fontana M, et al. The AADOCR position statement on topical fluoride. J Dent Res. (2025).

- Yeh CH, Lin CH, Ma TL, et al. Comparison between powered and manual toothbrush effectiveness. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 16 (2024): 381–396.

- Curia MC, Pignatelli P, D’Antonio DL, et al. Oral Porphyromonas gingivalis and Fusobacterium nucleatum abundance in cardiovascular prevention. Biomedicines. 10 (2022): 2144.

- Gimbrone MA Jr, García-Cardeña G. Endothelial cell dysfunction and atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 118 (2016): 620–636.

- Czesnikiewicz-Guzik M, Osmenda G, Siedlinski M, et al. Periodontitis and hypertension: Evidence from Mendelian randomization. Eur Heart J. 40 (2019): 3459–3470.

- Dutzan N, Kajikawa T, Abusleme L, et al. Dysbiotic microbiome triggers Th17-mediated oral immunopathology. Sci Transl Med. 10 (2018).

- Dutzan N, Abusleme L. T helper 17 cells as pathogenic drivers of periodontitis. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1197 (2019): 107–117.

- Rodrigues Neto SC, Piauilino AIF, Linhares HC, et al. C-reactive protein and leukocyte levels in odontogenic infections. J Maxillofac Oral Surg. (2025).

- Lanau N, Mareque-Bueno J, Zabalza M. Impact of nonsurgical periodontal treatment on blood pressure. Eur J Dent. 18 (2024): 517–525.

- Washio J, Takahashi N. Nitrite production from nitrate in the oral microbiome. In: Deng D, Do T, Dame-Teixeira N, eds. Oral Microbiome. Springer Nature Switzerland (2025): 89–101.

- Bowles EF, Burleigh M, Mira A, et al. Nitrate: The source makes the poison. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. (2024): 1–27.

- Döding A, Petzold A, Ciaston O, et al. Fighting age-associated bone loss in periodontitis. J Dent Res. (2025).

- Vassiliou EK, Gonzalez A, Garcia C, et al. Oleic acid reverses TNF-α-mediated inhibition of insulin production. Lipids Health Dis. 8 (2009).

- Ramirez-Tortosa MC, Quiles JL, Battino M, et al. Periodontitis and altered plasma fatty acids. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis. 20 (2010): 133–139.

- Drosatos-Tampakaki Z, Drosatos K, Siegelin Y, et al. Palmitic and oleic acid effects on osteoclastogenesis. J Bone Miner Res. 29 (2014): 1183–1195.

- Uwitonze AM, Rahman S, Ojeh N, et al. Oral manifestations of magnesium and vitamin D inadequacy. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 200 (2020): 1–9.

- Singleton R, Day G, Thomas T, et al. Maternal vitamin D deficiency and early childhood caries. J Dent Res. 98 (2019): 549–555.

- Cerf ME. Beta cell dysfunction and insulin resistance. Front Endocrinol. 4 (2013): 37.

- Sohn Y, Jeong HJ, Park J. Hyperinsulinemia and periodontitis in diabetes. J Dent Res. (2025).

- Yachmaneni A Jr, Jajoo S, Mahakalkar C, et al. Vascular consequences of diabetes in lower extremities. Cureus. 15 (2023): e47525.

- Hajishengallis G. Periodontitis: From immune subversion to systemic inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol. 15 (2014): 30–44.

- Takahashi N, Nyvad B. Role of bacteria in the caries process. J Dent Res. 90 (2011): 294.

- Gupta P, Gupta N, Pawar AP, et al. Role of sugar and sugar substitutes in dental caries. ISRN Dent. (2013): 1–5.

- Zhong Y, Kang X, Bai X, et al. Oral–gut–brain axis linking periodontitis and ischemic stroke. CNS Neurosci Ther. 30 (2024).

- Alahmari LA. Dietary fiber and cardiometabolic health. Front Nutr. 11 (2024): 1510564.

- Martín-Peláez S, Fitó M, Castañer O. Mediterranean diet and type 2 diabetes. Nutrients. 12 (2020): 2236.

- American Diabetes Association. Oral health and diabetes. Diabetes.org (2025).

- Lin CY, Chung CH, Chu HY, et al. Temporomandibular disorders in rheumatoid arthritis. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 31 (2017): e29–e36.

- Silvestre-Rangil J, Bagán L, Silvestre FJ, et al. Oral manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Oral Investig. 20 (2016): 2575–2580.

- Martinez-Martinez RE, Domínguez-Pérez RA, Sancho-Mata JE, et al. Dental caries and cariogenic bacteria in rheumatoid arthritis. Dent Med Probl. 56 (2019): 137–142.

- Nyvad B, Takahashi N. Integrated hypothesis of dental caries and periodontal diseases. J Oral Microbiol. 12 (2020): 1710953.

- Göktürk BA, Açıkalın Ş, Şanlıer N. Mediterranean diet and inflammatory index in rheumatoid arthritis. Front Nutr. 12 (2025).

- Gioia C, Lucchino B, Tarsitano MG, et al. Dietary habits in rheumatoid arthritis. Nutrients. 12 (2020): 1456.

- England BR, Smith BJ, Baker NA, et al. ACR guideline for exercise and diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res. 75 (2023): 1603–1615.

- Hu P, Lee EKP, Li Q, et al. Mediterranean diet and rheumatoid arthritis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 79 (2025): 888–896.

- Riaz R, Younis W, Uttra AM, et al. Anti-arthritic activity of linalool. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. (2025): 752.

- Van den Bruel K, Kulyk M, Neerinckx B, et al. Nutrition in inflammatory arthritis. Front Med. 12 (2025).

- Pu B, Gu P, Zheng C, et al. Coffee intake and rheumatoid arthritis. Front Nutr. 9 (2022).

- Vadell AKE, Barebring L, Hulander E, et al. Anti-inflammatory diet in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Clin Nutr. 111 (2020): 1203–1213.

- Martinez-Martinez RE, Abud-Mendoza C, Patiño-Marin N, et al. Periodontal bacterial DNA in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Periodontol. 36 (2009): 1004–1010.

- Punceviciene E, Rovas A, Puriene A, et al. Severity of periodontitis and rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Rheumatol. 40 (2021): 3153–3160.

- Winnier JJ, Rupesh S, Nayak UA, et al. Effects of tongue cleaning in children. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 6 (2013): 188–192.

- Avila M, Ojcius DM, Yilmaz Ö. The oral microbiota as a permanent guest. DNA Cell Biol. 28 (2009): 405–411.

- Pathak JL, Yan Y, Zhang Q, et al. Oral microbiome and respiratory diseases. Respir Med. 185 (2021).

- Mammen MJ, Scannapieco FA, Sethi S. Oral–lung microbiome interactions. Periodontol 2000. 83 (2020): 234–241.

- Iinuma T, Arai Y, Abe Y, et al. Denture wearing during sleep and pneumonia risk. J Dent Res. 94 (2015): 28S–36S.

- Gupta A, Saleena LM, Kannan P, et al. Oral diseases and respiratory health. J Dent. (2024): 148.

- Moraschini V, Calasans-Maia JDA, Calasans-Maia MD. Asthma and periodontal disease. J Periodontol. 89 (2018): 440–455.

- Lynch RJ. Zinc interactions with dental enamel. Int Dent J. 61 (2011): 46–54.

- Gorman RM. Zinc: Health benefits and food sources. Harvard Health Publishing (2025).

- Okuda K, Kimizuka R, Abe S, et al. Periodontopathic anaerobes in aspiration pneumonia. J Periodontol. 76 (2005): 2154–2160.

- Tian H, Zhang Z, Wang X, et al. Periodontitis-induced pulmonary inflammation in mice. Oral Dis. 28 (2022): 2294–2303.

- Cleveland Clinic. Periodontal disease. Cleveland Clinic (2025).

- Chait MM. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in older patients. World J Gastrointest Endosc. 2 (2010): 388–396.

- Clarrett DM, Hachem C. Gastroesophageal reflux disease. Mo Med. 115 (2018): 214–218.

- Beasley DE, Koltz AM, Lambert JE, et al. Evolution of stomach acidity and microbiome relevance. PLoS ONE. 10 (2015).

- Johns Hopkins Medicine. Wireless esophageal pH test (Bravo). Johns Hopkins Medicine (2022).

- Baliga S, Muglikar S, Kale R. Salivary pH as a diagnostic biomarker. J Indian Soc Periodontol. 17 (2013): 461–465.

- Watanabe M, Nakatani E, Yoshikawa H, et al. Oral soft tissue disorders and GERD. BMC Gastroenterol. 17 (2017).

- Fass R, McCallum RW, Parkman HP. Gastroparesis-related GERD management. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 5 (2009): 4–16.

- Newberry C, Lynch K. Diet in GERD management. J Thorac Dis. 11 (2019): S1594–S1601.

- Zalvan CH, Hu S, Greenberg B, et al. Alkaline water and Mediterranean diet vs PPI therapy. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 143 (2017): 1023–1029.

- Dundar A, Sengun A. Dental erosion in GERD. Afr Health Sci. 14 (2014): 481–486.

- Donovan T, Swift EJ. Dental erosion. J Esthet Restor Dent. 21 (2009): 359–364.

- Gao C, Kang J. Oral diseases and cognitive decline. In: Deng D, Do T, Dame-Teixeira N, eds. Oral Microbiome. Springer Nature Switzerland (2025): 171–183.

- Sadrameli M, Bathini P, Alberi L. Periodontitis and Alzheimer’s disease mechanisms. Curr Opin Neurol. 33 (2020): 230–238.

- Seitz MW, Listl S, Bartols A, et al. Dental conditions and chronic diseases. Prev Chronic Dis. 16 (2019).

- Gondivkar SM, Gadbail AR, Gondivkar RS, et al. Nutrition and oral health. Dis Mon. 65 (2019): 147–154.

- Morris MC, Tangney CC, Wang Y, et al. MIND diet and cognitive decline. Alzheimers Dement. 11 (2015): 1015–1022.

- Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Diet review: MIND diet. The Nutrition Source (2022).

- Lee YT, Lee HC, Hu CJ, et al. Periodontitis as a risk factor for dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 65 (2017): 301–305.

- Nazir MA. Periodontal disease prevalence and systemic associations. Int J Health Sci. 11 (2017): 72–80.

- Dong L, Ji Z, Hu J, et al. Oral microbiota shifts following tooth loss. BMC Oral Health. (2025): 213.

Impact Factor: * 5.8

Impact Factor: * 5.8 Acceptance Rate: 71.20%

Acceptance Rate: 71.20%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks