Management of Olecranon Fractures in the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Non-Operative, Limited Fixation and Operative Strategies

Mr. Praveen Rajan1, Mr. Vijay Patil2*, Mr. Yousef El-Tawil1, Mr. Srinath Pammi1, Mr. Aditya Vijay1, Dr. Umair Baig3, Dr. BK Balineni1, Dr. Venkata Nutalapati1

1Basildon University Hospital, Nether Mayne, Basildon SS16 5NL, UK

2 Royal Oldham Hospital, Rochdale Rd, Oldham OL1 2JH, UK

3Watford General Hospital, Vicarage Rd, Watford WD18 0HB, UK

*Corresponding Author: Mr. Vijay Patil, Royal Oldham Hospital, Rochdale Rd, Oldham OL1 2JH, UK.

Received: 01 December 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Published: 15 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Praveen Rajan, Vijay Patil, Yousef El-Tawil, Srinath Pammi, Aditya Vijay, Umair Baig, Bhargava Krishna Balineni, Venkata Nutalapati. Management of Olecranon Fractures in the Elderly: A Systematic Review and Meta- Analysis of Non-Operative, Limited Fixation and Operative Strategies. Journal of Orthopedics and Sports Medicine. 7 (2025): 585-592.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Olecranon fractures are common in the elderly, but the optimal management strategy remains controversial, with options ranging from non-operative care to standard operative fixation. This review aims to synthesie and compare outcomes of non-operative management, limited fixation, and operative fixation for olecranon fractures in patients aged ≥60 years.

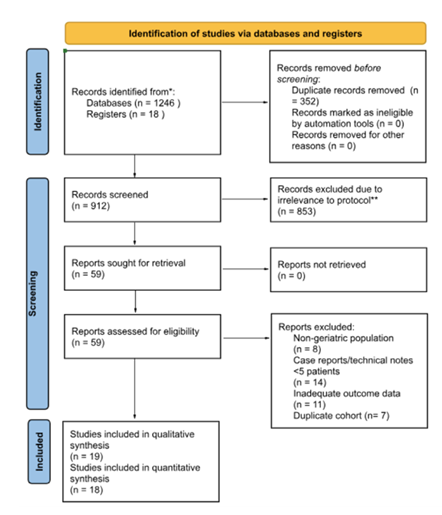

Methods: A systematic review was conducted according to PRISMA guidelines. Databases (PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Cochrane Library) were searched from inception to March 2025 for studies reporting functional outcomes, complications, or reoperations. Two reviewers independently screened studies, extracted data, and assessed quality using MINORS and Cochrane tools.

Results: Nineteen studies (710 patients) were included. Functional outcomes (DASH/QuickDASH, MEPS) were good to excellent across all groups. Non-operative management (11 studies, n=257) for stable fractures yielded mean DASH scores ~13.8 and high patient satisfaction despite frequent radiographic nonunion (up to 80%). Limited fixation techniques (3 studies, n=179), such as suture anchors, showed promising results with mean DASH ~9.6 and lower reoperation rates than tension-band wiring (TBW). Operative fixation (12 studies, n=276) achieved reliable union but carried higher complication rates, especially with TBW. Pooled analysis found no significant functional difference between operative (mean DASH 13.6) and non-operative (mean DASH 12.5) arms, but reoperation rates were higher for surgery (24.7% vs. 6.1%).

Conclusion: In elderly patients, non-operative management is safe and effective for stable, low-demand cases. Limited fixation offers a viable middle ground with stable fixation and low implant morbidity. Operative fixation, preferably with plating, remains indicated for unstable fractures. Treatment should be individualised based on fracture pattern, bone quality, and patient demands.

Keywords

Olecranon fracture; Elderly; Geriatric; Non-operative; Limited fixation; Tension band wiring; Plate fixation; Systematic review; Metaanalysis

Olecranon fracture articles; Elderly articles; Geriatric articles; Non-operative articles; Limited fixation articles; Tension band wiring articles; Plate fixation articles; Systematic review articles; Meta-analysis articles

Article Details

Introduction

Olecranon fractures account for approximately 10% of all upper extremity fractures in adults and represent the most common fracture of the proximal ulna [1]. The incidence increases with age, peaking in elderly populations due to osteoporosis and low-energy falls [2]. As life expectancy rises globally, the clinical and economic burden of these injuries in patients aged over 60 years is becoming increasingly significant [3].

The management of olecranon fractures in elderly patients presents unique challenges. Physiological aging is associated with reduced bone mineral density, thinner cortices, frailty, and higher prevalence of comorbidities, all of which complicate surgical intervention and affect outcomes [4].

While surgical fixation—typically with tension band wiring (TBW) or plate fixation—remains the standard of care for displaced fractures in younger adults [5], these techniques in older patients are often associated with high complication and re-operation rates, including hardware irritation, loss of fixation, and infection [6].

In contrast, non-operative treatment, traditionally reserved for minimally displaced fractures, has been increasingly reported as a reasonable option in low-demand elderly patients, with several studies showing preservation of function despite radiographic nonunion [7]. A growing body of evidence suggests that for selected patients, functional outcomes following conservative management may be comparable to those achieved with surgery, while avoiding the risks inherent to anaesthesia and fixation [8].

A third treatment concept—limited fixation techniques such as suture anchors, cerclage constructs, or suture-bridge methods—has emerged in response to concerns regarding hardware prominence and fixation failure in osteoporotic bone [9]. These methods aim to provide sufficient stability to permit early mobilisation while reducing implant-related morbidity. However, their role in routine practice remains uncertain due to limited comparative evidence.

Despite increasing interest in non-operative and limited fixation strategies, clinical decision-making is often inconsistent, influenced by surgeon preference, patient activity level, and institutional practice. Existing literature is heterogeneous in design, outcome measures, and follow-up, limiting the ability to draw firm conclusions [10]. The recently published SOFIE trial, the largest randomized controlled trial in this field, has fuelled further debate by suggesting that surgery may not always confer superior outcomes in elderly patients [11].

Given these uncertainties, a systematic synthesis of current evidence is warranted. This review aims to evaluate and compare the outcomes of non-operative management, limited fixation, and standard operative fixation for olecranon fractures in elderly patients, with reference to the Mayo classification system, which remains the most widely used framework for guiding treatment [12].

2. Methods

2.1 Protocol and Reporting

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The protocol was developed a priori, and the review process adhered to established methods for the synthesis of orthopaedic literature.

2.2 Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they met the following criteria:

- Population: Patients aged ≥60 years with olecranon fractures.

- Interventions: Non-operative management, limited fixation (including suture anchors, cerclage, or suture-bridge techniques), or operative fixation (tension band wiring, plate fixation).

- Comparators: Any of the above treatment modalities.

- Outcomes: Functional scores e.g., DASH [13], range of motion (ROM), radiographic union, complications, or reoperation rates.

- Study design: Randomised controlled trials (RCTs), prospective or retrospective cohort studies, and case series with ≥5 patients.

- Exclusion criteria included: cadaveric or biomechanical studies, technical notes without clinical outcomes, case reports, pediatric studies, and articles not available in English.

2.3 Search Strategy

A comprehensive literature search of PubMed, Embase, Scopus, and the Cochrane Library was performed from inception to March 2025. The search strategy combined MeSH terms and free-text keywords, including:

- "olecranon fracture"

- "elderly" OR "geriatric" OR "aged"

- "non-operative" OR "conservative"

- "internal fixation" OR "tension band wiring" OR "plate fixation"

- "suture anchor" OR "cerclage" OR "suture bridge"

Reference lists of all included studies and relevant reviews were also manually screened for additional eligible studies.

2.4 Study Selection

Two independent reviewers screened titles and abstracts. Full texts of potentially eligible articles were then assessed against the inclusion criteria. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or consultation with a third reviewer. See Figure 1 for PRISMA flow diagram.

2.5 Data Extraction

Data were extracted independently by two reviewers using a standardised form. Extracted variables included:

- Study design, year, and country

- Sample size and patient demographics (mean age, sex distribution, comorbidities)

- Fracture type (classified according to the Mayo classification)

- Intervention type (non-operative, limited fixation, operative fixation)

- Functional outcomes (DASH, QuickDASH, MEPS, ROM)

- Radiographic outcomes (union, malunion, nonunion)

- Complications and reoperation rates

- Length of follow-up

2.6 Quality Assessment

Methodological quality was assessed using the MINORS (Methodological Index for Non-Randomised Studies) criteria for observational studies and the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for randomised controlled trials. Each study was independently rated by two reviewers, with disagreements resolved by consensus. Risk of bias across studies was also assessed using funnel plots with contour lines.

2.7 Data Synthesis

A qualitative synthesis of all studies was performed. Results were stratified according to treatment modality (non-operative, limited fixation, operative fixation) and fracture stability (Mayo classification).

Quantitative synthesis was also performed and stratified according to treatment modality (operative or non-operative only due to feasibility reasons) for functional scores, re-operation rates and non-union. Eligible studies included adult patients with at least one functional score reported at ≥6 months post-treatment. When multiple functional scores were available, DASH or QuickDASH was prioritised to maintain consistency; other scales (e.g., MEPS, OES) were excluded from pooling due to differing directionality. Data extracted included mean, standard deviation (SD), and sample size (N) for each arm. Where SDs were missing, we imputed values using pooled SDs within ArmType × OutcomeName groups, following Cochrane Handbook guidance for handling missing variance. If no group-specific SD was available, an overall pooled SD was used. For studies with multiple subgroups (e.g., Batten 2016, LinanPadilla 2017), we combined data into single weighted means per arm. Outcomes were harmonised to a 0–100 scale (lower = better function). Meta-analysis was performed using inverse-variance weighting under a random-effects model (DerSimonian–Laird), given anticipated clinical heterogeneity. We also calculated fixed-effect estimates for sensitivity. Between-study heterogeneity was quantified using I². For complications, event counts and sample sizes were extracted for each arm. Proportions were logit-transformed with continuity correction (+0.5 for zero-event arms) and variance was estimated. Pooled estimates were calculated using inverse-variance weighting under fixed-effect and DerSimonian–Laird random-effects models. Between-study heterogeneity was assessed using I² also. Results were back-transformed to proportions for interpretability. Artificial Intelligence tools (ChatGPT-5 via Microsoft Co-Pilot) was used to aid this process.

3. Results

3.1 Qualitative Synthesis

Nineteen studies involving 710 elderly patients (mean age range 69–89 years) were included: eight prospective cohorts, ten retrospective series, and one randomised controlled trial (SOFIE). Fracture patterns were predominantly Mayo type II, with some type I and type III injuries. Follow-up ranged from 12 months to 6 years. Outcomes were assessed using DASH or QuickDASH, Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS), Oxford Elbow Score (OES), and range of motion (ROM), though reporting formats varied considerably.

By treatment modality, 11 studies (n=257) evaluated non-operative management, three studies (n=179) assessed limited fixation techniques, and 12 studies (n=276) reported outcomes of operative fixation using tension-band wiring (TBW), plate constructs, or other rigid methods. Several studies included more than one treatment arm; pooled counts therefore reflect numbers treated per modality rather than mutually exclusive cohorts.

Non-operative management consistently produced acceptable functional recovery in elderly, low-demand patients with Mayo type I–II fractures. DASH/QuickDASH scores ranged from 2.9 to 26, and MEPS values were typically >90, indicating good to excellent outcomes. The SOFIE trial and Duckworth et al. reported no significant functional differences between operative and non-operative arms. Most patients regained a functional flexion-extension arc of 120–140°, with small extension lags (–7° to –10°). Radiographic nonunion was frequent (up to 70–80%) but rarely symptomatic, and reoperation rates were very low (<5%).

Limited fixation techniques, including suture-based and cerclage constructs, yielded QuickDASH scores of 6.4–16.3 and MEPS values of 85–95. Flexion-extension arcs averaged 120–136°, with minimal functional deficit. Union rates were high, and implant-related complications were uncommon. Wenger et al. reported significantly fewer reoperations with cerclage fixation (6%) compared with TBW (23%) in the same series, highlighting the advantage of low-profile constructs in osteoporotic bone.

Operative fixation achieved excellent union rates (>90% for plating) and high functional scores (DASH/QuickDASH 5.8–23.5; MEPS 90–96), though not superior to non-operative care in randomised comparisons. ROM was broadly similar across groups, with flexion arcs of 120–140° and mild residual extension lag. TBW carried the highest complication and reoperation rates (up to 30%), largely due to hardware irritation and fixation failure in osteoporotic bone. Plate fixation provided superior mechanical stability for comminuted Mayo IIB–III fractures, with lower reoperation risk than TBW, though wound or infection complications occurred in 2–5% of cases.

Descriptive pooled synthesis of study-level means suggested broadly comparable functional outcomes across modalities: non-operative DASH/QuickDASH ≈13.8 and MEPS ≈92.9; limited fixation DASH/QuickDASH ≈9.6 and MEPS ≈86.0; operative fixation DASH/QuickDASH ≈12.9 and MEPS ≈92.1. ROM was consistently functional (120–140°) with small extension deficits (<10°), though reporting was heterogeneous. These pooled estimates are descriptive and should not be interpreted as formal meta-analytic effect sizes.

Overall, non-operative care provided satisfactory function despite frequent nonunion and minimal need for secondary surgery, limited fixation offered a favourable balance of stability and low implant morbidity, and operative fixation—particularly plating—remains indicated for unstable or comminuted fractures, albeit with higher complication risk than less invasive strategies.

3.2 Pairwise Meta-Analysis

3.2.1 Functional outcomes

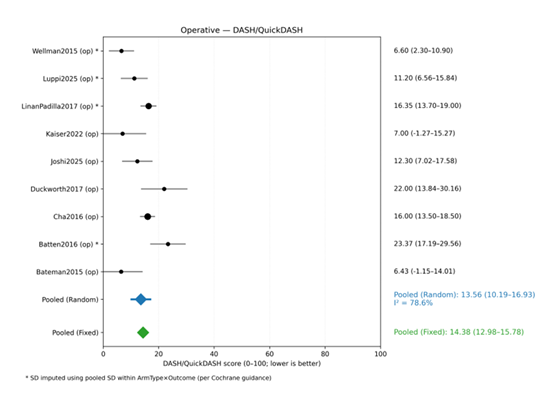

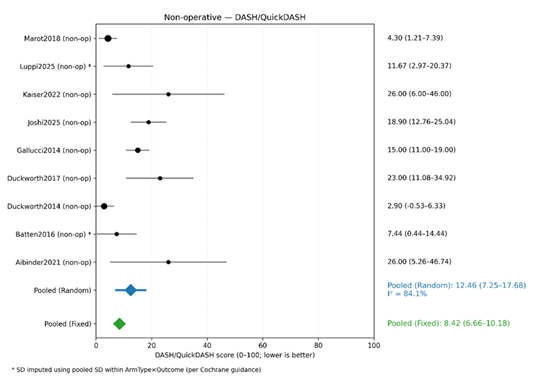

A total of 18 studies contributed DASH/QuickDASH data for operative and non-operative arms. After aggregation and imputation, 9 operative cohorts and 9 non-operative cohorts were included in pooled analyses (Figure 2 and 3).

- Operative arms: The random-effects pooled mean DASH/QuickDASH score was 13.6 (95% CI: 10.2–16.9), indicating low residual disability. Heterogeneity was substantial (I² = 78.6%, τ² = 18.8), reflecting variability in fixation methods and follow-up duration (Figure 2).

Non-operative arms: The pooled mean was 12.5 (95% CI: 7.3–17.7), with similarly high heterogeneity (I² = 84.1%, τ² = 43.9) (Figure 3).

Fixed-effect estimates were slightly lower for non-operative arms (8.4) and similar for operative arms (14.4), but these are less reliable given heterogeneity.

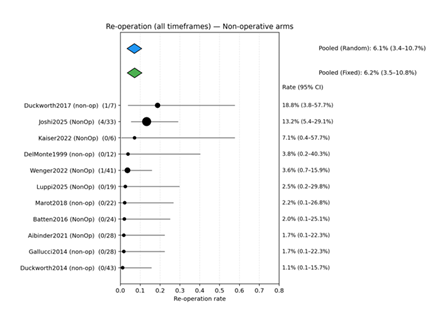

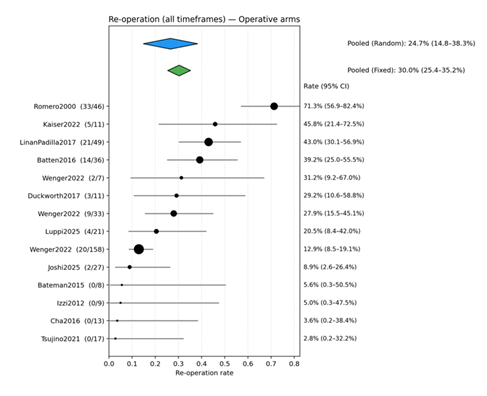

3.2.2 Re-operation

Eleven non-operative arms (n ≈ 241) and fourteen operative arms (n ≈ 467) reported re-operation rates. Among non-operative arms, the pooled re-operation rate was 6.2% (95% CI 3.5–10.8%) under a fixed-effect model and 6.1% (95% CI 3.4–10.7%) under a random-effects model, with minimal heterogeneity (I² = 1.9%) (Figure 4). In contrast, operative arms demonstrated a pooled re-operation rate of 30.0% (95% CI 25.4–35.2%) under a fixed-effect model and 24.7% (95% CI 14.8–38.3%) under a random-effects model, with substantial heterogeneity (I² = 82.2%, τ² = 0.9988) (Figure 5). This variability likely reflects differences in surgical technique, patient selection, and follow-up duration.

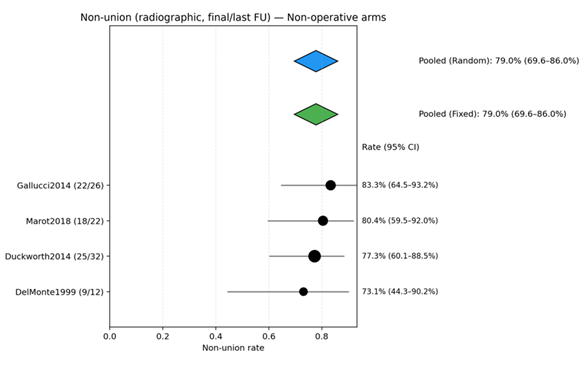

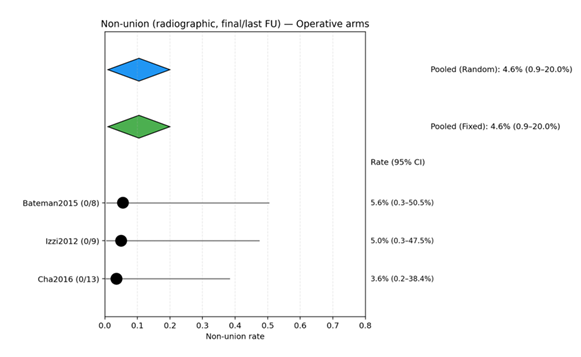

3.2.3 Non-union

Four non-operative arms (n = 92) yielded a pooled non-union rate of 79.0% (95% CI 69.6–86.0%) (Figure 6), whereas three operative arms (n = 30) showed a pooled rate of 4.6% (95% CI 0.9–20.0%) (Figure 7). Heterogeneity was negligible for both groups. These findings indicate that non-union is common after non-operative care but rare following operative fixation.

4. Discussion

This systematic review of 19 studies encompassing 710 elderly patients with olecranon fractures demonstrates that non-operative and limited-fixation strategies can yield functional outcomes comparable to conventional operative fixation in carefully selected cases [14]. Mean DASH/QuickDASH scores and Mayo Elbow Performance Scores were consistently high across all treatment groups, while range of motion was preserved in most patients. These findings challenge the historical assumption that anatomic reduction and rigid fixation are mandatory for satisfactory elbow function in older adults. Our results align with earlier population studies showing that many elderly patients maintain good function despite radiographic non-union after non-operative care [14-23]. Randomised evidence remains limited but supportive: the SOFIE trial [11] found no significant functional difference between surgical and non-operative management for displaced Mayo II fractures, echoing our pooled observations. Similarly, Cha et al. [24] have reported favourable outcomes with low-morbidity limited fixation, particularly when soft-tissue quality or comorbidities complicate standard plating.

The current review also highlights important nuances. While non-operative care is effective for stable Mayo I–IIA injuries in low-demand patients, unstable or comminuted fractures (Mayo IIB–III) generally require rigid fixation to restore joint congruity and allow early motion. Within the operative arm, contemporary literature favours low-profile plate constructs over tension-band wiring in osteoporotic bone, owing to lower rates of symptomatic hardware and reoperation [28].

In quantitative terms, our synthesis indicates that both operative and non-operative management are associated with favourable long-term functional outcomes, with pooled DASH/QuickDASH scores consistently in the low teens. The absolute difference between strategies was small (≈1 point) and unlikely to be clinically meaningful in routine practice; however, no direct comparative meta-analysis was performed, and the evidence is therefore insufficient to infer superiority of one approach over the other for function alone. Between-study heterogeneity was substantial (I² > 75%), reflecting differences in fracture complexity, patient selection, surgical technique, rehabilitation protocols, and outcome assessment.

A consistent trade-off emerged between radiographic union and the burden of subsequent procedures. Non-operative treatment was associated with high non-union rates yet a low risk of reoperation, implying that many patients—particularly those who are frail or have low functional demands—tolerate radiographic non-union without appreciable detriment to patient-reported function. By contrast, operative fixation yielded excellent union rates but a materially higher likelihood of reoperation, most commonly for hardware irritation or implant-related failure. Technique-specific signals suggest that tension-band wiring may carry higher reoperation rates than plate or cerclage fixation [6,26], which likely contributes to heterogeneity and should inform implant choice when surgery is indicated.

Framed clinically, these data support a fracture-specific, patient-centred algorithm in which non-operative management is appropriate for stable or minimally displaced fractures in low-demand older adults who prioritise pain control, independence, and avoidance of further procedures; where modest displacement confers some instability yet full plating may be excessive, limited fixation provides a pragmatic middle ground that can achieve stability while potentially reducing implant-related morbidity; and for unstable or comminuted patterns—particularly in patients with higher functional demands or where instability threatens extensor mechanism continuity—modern plate fixation is justified to achieve anatomic restoration and reliable union. This schema makes explicit the trade-offs between functional goals, tolerance for reoperation, fracture morphology, bone quality, and patient priorities rather than defaulting to a uniform strategy.

Several limitations warrant emphasis and temper the certainty of these conclusions. Only one randomised controlled trial met inclusion criteria; most included studies were small prospective or retrospective series, limiting causal inference and amplifying susceptibility to confounding by indication. Overlapping cohorts and potential double-counting across treatment groups were present in several studies that reported both operative and non-operative arms; thus, per-group totals in the dataset represent numbers treated within each modality rather than mutually exclusive populations, and pooled counts should be interpreted accordingly. Heterogeneity in outcome reporting—both in metric choice and in format—prevented formal meta-analysis for several endpoints and required descriptive aggregation. Range-of-motion synthesis was particularly uncertain given inconsistent reporting. The imputation of missing dispersion metrics, while methodologically defensible and supportive of broader inclusion, inevitably widens uncertainty around variance estimates. Definitions of union and reoperation varied across studies, follow-up schedules were inconsistent, and data for plate and cerclage techniques remained relatively sparse, limiting the precision of technique-level estimates. Selective outcome reporting and publication bias are possible. Finally, most studies originated from specialised centres, potentially constraining generalisability to broader practice environments.

Future work should prioritise head-to-head randomised comparisons of non-operative care, limited fixation, and contemporary plate constructs within clearly defined fracture patterns and patient profiles; adopt standardised definitions and timepoints for union, reoperation, and complications; foreground patient-reported outcomes alongside performance metrics and quality of life; and incorporate prespecified subgroup analyses by fracture morphology, age, bone quality, and comorbidity. Health economic evaluations that model initial treatment costs, reoperation rates, rehabilitation demands, and longer-term societal impacts will further clarify which patients derive the greatest value from each strategy.

5. Conclusion

On balance, management of olecranon fractures in elderly patients should be individualised according to fracture pattern, comorbidities, bone quality, and functional demands. Current evidence demonstrates that non-operative treatment is a safe and effective option for low-demand older adults with minimally displaced or stable fractures (Mayo I–IIA), delivering satisfactory functional outcomes despite frequent radiographic non-union and minimising re-operation risk. Limited fixation offers a pragmatic alternative for displaced but structurally stable fractures, combining high union rates with low implant-related morbidity and good recovery. For unstable or comminuted patterns (Mayo IIB–III), operative fixation—preferably with modern plate constructs—remains the most reliable means of restoring joint congruity and extensor continuity while reducing hardware-related complications compared with traditional tension-band wiring. Overall, these findings support a fracture-specific, patient-centred approach that prioritises non-operative or minimally invasive strategies in frail or low-demand patients and reserves full operative fixation for unstable injuries. Given the heterogeneity, observational design, and incomplete reporting across existing studies, high-quality randomised trials with standardised outcomes and patient-reported measures are urgently needed to refine indications and optimise care in this population.

Acknowledgements:

Mr. Praveen Rajan and Mr. Vijay Patel contributed equally to leading on this review and should be considered co-first authors.

Conflict of Interest:

Authors of this manuscript declare no conflict of interests.

References

- Duckworth AD, Clement ND, Aitken SA, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM. The epidemiology of fractures of the proximal ulna. Injury. 2012;43(3):343–346. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2011.10.017 [europepmc.org], [sci-hub.st]

- Karlsson MK, Hasserius R, Sundh D, et al. Characteristics of fall patients who fracture their femoral neck or wrist: data from 3,098 consecutive fall patients of the BETA-cohort. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2020;140:1651–1657. doi:10.1007/s00402-020-03424-2

- Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM. Global Forum: Fractures in the Elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98(9):e36. doi:10.2106/JBJS.15.00793 [boneandjoint.org.uk], [pure.ed.ac.uk]

- Ayers C, Kansagara D, Lazur B, et al. Effectiveness and safety of treatments to prevent fractures in people with low bone mass or primary osteoporosis. Ann Intern Med. 2023;176(2):605–616. doi:10.7326/M22-0684

- Hak DJ, Golladay GJ. Olecranon fractures: treatment options. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(4):266–275. doi:10.5435/00124635-200007000-00007 [europepmc.org], [scirp.org]

- Duckworth AD, Clement ND, White TO, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM. Plate versus tension-band wire fixation for olecranon fractures: a prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(15):1261–1273. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.00773 [scholar.google.com], [sci-hub.st]

- Gallucci GL, Piuzzi NS, Slullitel PAI, et al. Non-surgical functional treatment for displaced olecranon fractures in the elderly. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(4):530–534. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.96B4.33339 [boneandjoint.org.uk], [pure.ed.ac.uk]

- Savvidou OD, Koutsouradis P, Kaspiris A, Naar L, Chloros GD, Papagelopoulos PJ. Displaced olecranon fractures in the elderly: outcomes after non-operative treatment - a narrative review. EFORT Open Rev. 2020 Aug 1;5(7):391-397. doi: 10.1302/2058-5241.5.190041.

- Nazifi O, Gunaratne R, D’Souza H, Tay A. The Use of High Strength Sutures and Anchors in Olecranon Fractures: A Systematic Review. Geriatric Orthopaedic Surgery & Rehabilitation. 2021;12. doi:10.1177/2151459321996626

- Rantalaiho IK, Miikkulainen AE, Laaksonen IE, Äärimaa VO, Laimi KA. Treatment of Displaced Olecranon Fractures: A Systematic Review. Scandinavian Journal of Surgery. 2019;110(1):13-21. doi:10.1177/1457496919893599

- Joshi MA, Le M, Campbell R, Sivakumar B, Limbers J, Harris IA, Symes M. Surgery for Olecranon Fractures in the Elderly (SOFIE): Results of the SOFIE Randomized Controlled Trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2025;107(5):452–458. doi:10.2106/JBJS.24.00655

- Morrey BF. Current concepts in the treatment of fractures of the radial head, the olecranon, and the coronoid. Instr Course Lect. 1995;44:175–185. doi:10.2106/00004623-199502000-00019 [europepmc.org], [scirp.org]

- Hudak PL, Amadio PC, Bombardier C; American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons Upper Extremity Collaborative Group. Development of an upper extremity outcome measure: the DASH. Am J Ind Med. 1996;29(6):602–608. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0274(199606)29:6<602::AID-AJIM4>3.0.CO;2-L [mayoclinic...erpure.com], [researchgate.net]

- Duckworth AD, Clement ND, White TO, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM. Plate versus tension-band wire fixation for olecranon fractures: a prospective randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2017;99(15):1261–1273. doi:10.2106/JBJS.16.00773 [scholar.google.com], [sci-hub.st]

- Gallucci GL, Piuzzi NS, Slullitel PAI, et al. Non-surgical functional treatment for displaced olecranon fractures in the elderly. Bone Joint J. 2014;96-B(4):530–534. doi:10.1302/0301-620X.96B4.33339 [boneandjoint.org.uk], [pure.ed.ac.uk]

- Marot V, Bayle-Iniguez X, Cavaignac E, et al. Results of non-operative treatment of olecranon fractures in the elderly. Int Orthop. 2018;42:915–920. doi:10.1016/j.otsr.2017.10.015 [hal.science]

- Veras Del Monte L, Sirera Vercher M, Busquets Net R, Castellanos Robles J, Carrera Calderer L, Mir Bullo X. Conservative treatment of displaced fractures of the olecranon in the elderly. Injury. 1999 Mar;30(2):105-10. doi: 10.1016/s0020-1383(98)00223-x.

- Luppi V, Regis D, Maluta T, Sandri A, Trivellato A, Mirabile A, Magnan B. Conservative versus surgical treatment for displaced olecranon fractures in the elderly: a retrospective study and a review of the literature. Musculoskelet Surg. 2025 Mar;109(1):63-70. doi: 10.1007/s12306-024-00853-x. Epub 2024 Jul 31.

- Batten T, Barlow JD, Van Heest AE. Outcomes of nonoperative treatment of displaced olecranon fractures in elderly patients. Curr Orthop Pract. 2016;27(1):103–106. doi:10.1097/BCO.0000000000000307 [journals.lww.com]

- Kaiser P, Stock K, Benedikt S, Kastenberger T, Schmidle G, Arora R. Retrospective comparison of conservative treatment and surgery for widely displaced olecranon fractures in low-demanding geriatric patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2022 Oct;142(10):2659-2667. doi: 10.1007/s00402-021-04031-7. Epub 2021 Jul 5.

- Wenger D, Cornefjord G, Rogmark C. Cerclage fixation without K-wires is associated with fewer complications and reoperations compared with tension band wiring in stable displaced olecranon fractures in elderly patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2022 Oct;142(10):2669-2676. doi: 10.1007/s00402-021-04027-3. Epub 2021 Jul 8.

- Aibinder WR, Sims LA, Athwal GS, King GJW, Faber KJ. Outcomes of nonoperative management of displaced olecranon fractures in medically unwell patients. JSES Int. 2021 Jan 10;5(2):291-295. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2020.11.001.

- Duckworth AD, Bugler KE, Clement ND, Court-Brown CM, McQueen MM. Nonoperative management of displaced olecranon fractures in low-demand elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014 Jan 1;96(1):67-72. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01137. PMID: 24382727.

- Cha SM, Shin HD, Lee JW. Application of the suture bridge method to olecranon fractures with a poor soft-tissue envelope around the elbow: Modification of the Cha-Bateman methods for elderly populations. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016 Aug;25(8):1243-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2016.02.011. Epub 2016 Apr 12.

- Izzi J, Athwal GS. An off-loading triceps suture for augmentation of plate fixation in comminuted osteoporotic fractures of the olecranon. J Orthop Trauma. 2012 Jan;26(1):59-61. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318214e64c.

- Romero JM, Miran A, Jensen CH. Complications and re-operation rate after tension-band wiring of olecranon fractures. J Orthop Sci. 2000;5(4):318-20. doi: 10.1007/s007760070036.

- Linan-Padilla A, Barrera-Ochoa S, Galtes-Vallmajor I, et al. Plate fixation for displaced olecranon fractures in patients older than 75 years. Injury. 2017;48:S20–S24. doi:10.1016/j.injury.2017.07.012

- Wise KL, Peck S, Smith L, Myeroff C. Locked plating of geriatric olecranon fractures leads to low fixation failure and acceptable complication rates. JSES Int. 2021 Apr 16;5(4):809-815. doi: 10.1016/j.jseint.2021.02.013.

- Tsujino T, Kikuchi Y, Murase T, et al. A new off-loading triceps suture technique for comminuted olecranon fractures in the elderly. J Orthop Sci. 2021;26:311–315. doi:10.1016/j.jos.2021.01.006

- Wellman DS, Lazaro LE, Bawa M, et al. Comminuted olecranon fractures: comparison of tension band wiring and plate fixation. J Orthop Trauma 29 (2015): e263-e268.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 73.64%

Acceptance Rate: 73.64%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks