The Effects of Puberty Blocking Treatment (Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone agonist) on Reproductive Function in Young Female Rats

Brandon Jones Ph.D1,2*, David Hydock Ph.D2

1College of Health and Movement Science, Exercise Science Department, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia, USA

2College of Natural and Health Science, Department of Kinesiology, Nutrition, and Dietetics, University of Northern Colorado, Greeley, Colorado, USA

* Corresponding Author: Brandon Jones, Ph.D., College of Health and Movement Science, Exercise Science Department, Marshall University, Huntington, West Virginia, USA.

Received: 09 December 2025; Accepted: 16 December 2025; Published: 23 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Brandon Jones, David Hydock. The Effects of Puberty Blocking Treatment (Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone agonist) on Reproductive Function in Young Female Rats. Archives of Clinical and Biomedical Research. 9 (2025): 552-558.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

This study investigated the effects of puberty blocking treatment on reproductive morphology and function in young female rats. Reproductive recovery of the ovaries and uteri of peri-pubescent female rats were examined by comparing H&E-stained sections. In addition to reproductive function recovery, after drug withdrawal. Four-week old peri-pubescent female Sprague Dawley rats (n=32) were given daily injections of the gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist, triptorelin or saline. After four weeks of treatment a group of rats were euthanized, and the uterus and ovaries were removed for H&E staining. Additional rats were taken off the treatment for 4 weeks to examine recovery. The final group was taken off puberty blocking treatment and housed with fertile males. Puberty blocking treatment led to a reduction in the mass of uteri and ovaries which recovered after 4-weeks withdrawal. The ovaries of the treatment group exhibited a disruption in follicle development and corpora lutea health which recuperated after 4-weeks of withdrawal. No significant difference in pregnancy rate was detected; however, both the number of days until pregnancy detection and number of days until giving birth were considerably longer in puberty blocked rats following withdrawal. The number of pups per litter was also significantly reduced by drug treatment but no abnormalities were observed in the pups. Young female rats treated with a puberty blocker had significantly delayed development of the reproductive organs, which recovered after 4 weeks of drug withdrawal. A minor disruption in reproductive function was detected immediately following drug withdrawal.

Keywords

<p>Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone Agonist (GnRHa); Puberty blocker; Reproductive recovery; Transgender youth</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

The increased prevalence of youth identifying as transgender has emphasized the need to better understand the health and wellbeing of this growing population. Transgender individuals do not identify with the sex designated at birth. The conflict between designated sex at birth and feelings of being male, female, or nonconforming gender (defined as gender dysphoria) can cause psychological distress [1,2]. In response to the psychological distress associated with development of secondary sex characteristics, some transgender youth choose to manipulate sex hormone production with a gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) which serves as a puberty blocker [3].

Transgender youth treated with a puberty blocker (PB) report an increased quality of life and psychological well-being [2]; however, the chronic effects of long term GnRHa treatment are relatively unknown. The reversibility of GnRHa treatment on reproductive capabilities is especially important for transgender youth who may decide to discontinue treatment later in life and revert back to living as their sex designated at birth, known as “de-transitioning” [3].

The relatively novel use of GnRHa in transgender youth, requires further research to understand the chronic effects of GnRHa treatment. GnRHa drugs such as triptorelin desensitizes the pituitary gland to GnRH, significantly decreasing LH and FSH release [4,5]. In biological female adult humans, triptorelin can decrease LH, FSH, and estradiol to prepubertal concentrations after 3 months of treatment [6]. Ovary size can decrease by 65% during treatment while uterus dimensions can be reduced by 40% [7,8]. In young female rats, GnRHa treatment delays puberty, as demonstrated by arrest of uterine growth, delay of vaginal opening, absence of normal estrous cycle, and atrophy of the ovaries and uterus [9].

Early research in adults taking GnRHa indicates that its effect on the female reproductive tract is reversible within 1 year of treatment withdrawal [8,10]. Six months after discontinuing a one-year GnRHa treatment regime, females with precocious puberty recovered normal LH, FSH, inhibin, and anti-mullerian hormone concentrations [11]. The regression of the female reproductive tract mass and function has also been shown to be reversible. In young and old female rats treated with GnRHa, uterine and ovary weight recovered within 10 - 20 days of GnRHa cessation [9]. Long term treatment of GnRHa also had no effect on the number of pregnancies or litter size in adult rats [10].

The purpose of this study was to investigate the effects of GnRHa treatment on reproductive health and fertility in young female rats. Understanding the impact on fertility and morphological alterations is important in supporting transgender youth deciding to take a puberty blocker. The chronic effect of puberty blocker treatment after drug withdrawal is important to transgender youth who decide to de-transition to their gender assigned at birth.

2. Material and Methods

2.1 Design

In this intervention based study, young female rats were given a puberty blocking treatment (GnRHa) for 4-weeks to examine its influence on morphology of the ovaries and uteri in addition to recovery after withdrawal. Researchers hypothesized morphology and reproductive function would not recover completely after withdrawal. The research procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Northern Colorado (2001-DH-R-23) and was in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act. Young (3-week old) female rats (n=32) and pubescent (7-week old) male (n=12) rats were purchased from Envigo (Indianapolis, Indiana) and housed on a 12:12 light to dark cycle with water and rat chow given ad libitum. The first week served as an acclimatization period before the now 4-week old female rats were randomly assigned to the control 8-week group (CON-8), puberty blocker treatment group (PB), control 12-week group (CON-12), puberty blocker withdrawal group (PB-W), mating control group (M-CON), or mating puberty blocker treatment group (M-PB).

2.2 Subject treatment

Beginning at 4-weeks of age, the PB, PB-W, and M-PB groups started receiving 100 μg subcutaneous injection of the GnRH agonist triptorelin per day (100 μL of 1 mg/mL) while the CON-8, CON-12, and M-CON group received 100 μL injections of saline as a placebo. Treatment with GnRHa or saline continued for 4-weeks. At 8-weeks of age all animals stopped treatment. The CON-8 and PB animals were euthanized with sodium pentobarbital (50 mg/kg). The uterus and ovaries were removed, cleaned, weighed, and photographed. The right ovary and uterine horn were fixed in formalin for paraffin embedding before hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. The CON-12 and PB-W rats were taken off GnRHa/saline treatment at 8-weeks of age and observed for an additional 4-weeks before sacrifice. The M-CON and M-PB animals were paired with one fertile male (12-weeks of age). One fertile male was housed with each treated and control female. Fertility was quantified by the number of pregnancies per group, days to pregnancy detection, days till giving birth, litter size, and pup survival rate.

2.3 Tissue morphology

On sacrifice day, the right ovary and uterine horn were dissected, cleaned, weighed and photographed before being fixed in formalin. The samples were then embedded in paraffin, sectioned, mounted on slides, and stained with H&E for morphological analysis by iHisto Inc. Three H&E-stained sections per tissue were analyzed for morphology. The right uterine horn’s morphological health was evaluated by uterine endometrial/myometrial thickness and cross-sectional area. Qupath open source software for digital pathology image analysis was used to quantify cross-sectional area for the uteri and ovaries by selecting the entire stained section area with the wand tool. Endometrial and myometrial thickness were quantified with Qupath software by measuring the width on both sides of the lumen. The right ovary’s morphological health was assessed by counting the number of primary follicles, secondary follicles, and tertiary follicles in conjunction with corpus luteum number and cross-sectional area. Primary follicles were identified as an oocyte surrounded by a single layer of columnar cells. Secondary follicles were recognized by proliferation of the granulosa cell layer and tertiary follicles were identified by development of the follicular antrum.

2.4 Breeding

Once the 4-week GnRHa treatment period ceased, one fertile male rat (12-weeks old) was housed with each M-PB and M-CON female for a maximum of 6-weeks. Pregnancy was confirmed by daily visual inspection for abdominal enlargement and mammary development along with body mass changes. The number of pregnancies per group, days to pregnancy detection, days until giving birth, litter size, and pup survival rate were used to determine fertility.

2.5 Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation. A one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed on uterine morphology (myometrial thickness, endometrial thickness, uterine cross-sectional area, mass), ovarian morphology (primary follicles, secondary follicles, tertiary follicles, corpora lutea, and ovary cross-sectional area, mass), and weekly body mass. A Bonferroni post-hoc test gave further insight. A chi-square test was used to examine the effects of GnRHa treatment on achieving pregnancy and pup survival rate. A t-test was used to identify the effect of GnRHa treatment on number of days to pregnancy detection, number of days to giving birth, litter size, and pup mass after puberty blocker withdrawal. All statistical analyses used IBM SPSS statistics software and significance was set at the α=0.05 level.

3. Results

3.1 Uterine and Ovarian Mass

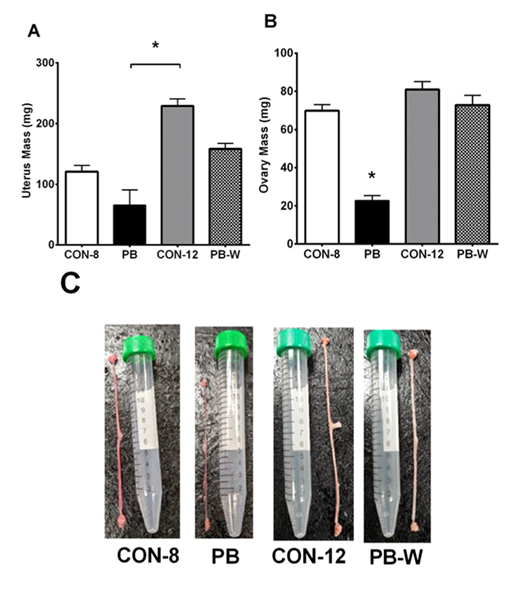

A gross visual delay of uterine and ovarian development was observed in PB animals and recovery of the reproductive organs from GnRHa treatment was evident in PB-W animals (Figure 1). These observed visual differences were supported by measurements of tissue mass. The uterine mass of PB animals was significantly less than CON-12 uteri (p= .001). Ovarian mass was also decreased by puberty blocker treatment, which recovered after 4-weeks of PB withdrawal. Ovaries from PB animals had a reduction in mass relative to CON-8 (p< .001), CON-12 (p< .001), and PB-W (p< .001).

Note: (A) Uterus Mass, (B) Ovary Mass. CON-8: control at 8-weeks-old (n=4), PB: puberty blocker (n=4), CON-12: control at 12-weeks-old (n=6), PB-W: puberty blocker withdrawal (n=6). *p< .05.

3.2 Uterine morphology

Analysis of H&E stained uterine sections found puberty blocking treatment significantly altered morphology (Figure 2). Stained uteri from PB animals had smaller cross-sectional area than CON-12 (p= .001) and PB-W (p= .005). The difference between PB and CON-8 uterine area was not significant (p= .118).

Note: (A) Uterine Cross-sectional Area, (B) Myometrial Thickness, (C) Endometrial Thickness, CON-8: control at 8-weeks-old (n=4), PB: puberty blocker (n=4), CON-12: control at 12-weeks-old (n=6), PB-W: puberty blocker withdrawal (n=6). Endo: Endometrium, Myo: Myometrium *p< .05.

The myometrium and endometrium were both reduced by puberty blocking treatment. Myometrial thickness of the uterus was significantly less in PB animals compared to CON-8 (p= .027), CON-12 (p= .003), and 4-weeks following PB withdrawal (PB-W) (p = .018). The endometrium of PB animals showed a significant reduction in thickness compared to CON-12 (p= .010), and PB-W (p= .024). Endometrial thickness between PB and CON-8 approached significance (p= .087), but the difference was not significant.

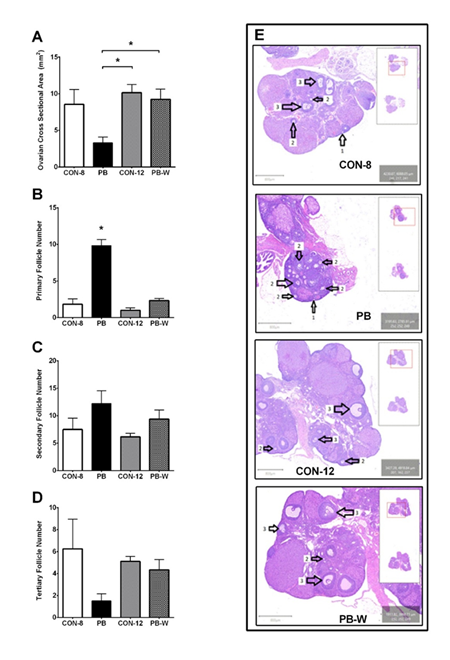

3.3 Ovarian morphology

Analysis of H&E stained ovarian sections found puberty blocking treatment significantly altered morphology (Figure 3). The cross-sectional area of ovarian samples from PB animals was significantly less than CON-12 (p= .020) and PB-W (p= .038) ovaries (Supplementary File). Animals receiving the puberty blocker also had a significantly greater number of primary follicles than CON-8 (p< .001), CON-12 (p< .001), and PB-W (p< .001). No significant difference was found in the number of secondary or tertiary follicles. The corpora lutea from the ovaries of PB animals suggests a disruption in luteal health that recovered after withdrawal (PB-W) (Supplementary Figure 3).

Note: (A) Ovarian Cross-sectional Area, (B) Number of Primary Follicles (C) Number of Secondary Follicles, (D) Number of Tertiary Follicles. CON-8: control at 8-weeks-old (n=4), PB: puberty blocker (n=4), CON-12: control at 12-weeks-old (n=6), PB-W: puberty blocker withdrawal (n=6). 1: Primary Follicle, 2: Secondary Follicle, 3: Tertiary Follicle. *p< .05.

3.4 Pregnancy Outcomes

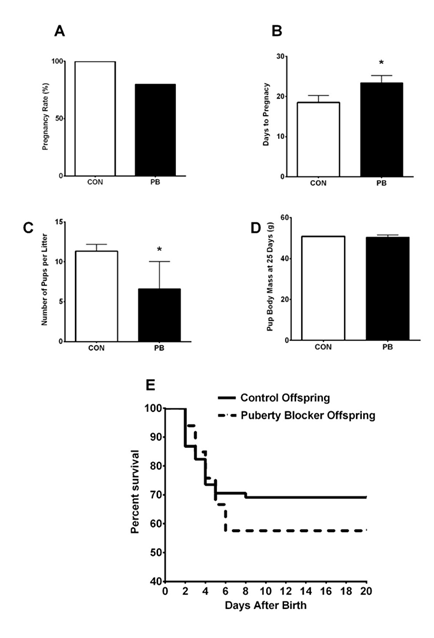

Investigation of reproductive function after PB withdrawal did not find a significant difference in the pregnancy rate between young female rats treated with GnRHa and control rats (p= .296) (Figure 4). The number of days until pregnancy detection was significantly longer in animals treated with the PB (p= .034). Additionally, the number of days from the introduction of the male until birth of the litter was also significantly longer in young rats treated with the GnRHa (p = .049) (Supplementary Figure 4). The number of pups per litter was found to be significantly different between PB and control animals (p= .020) (Figure 4). The average body mass of pups at 25-days old (p= .646) and survival rate (p= .253) of the pups was not influenced by the dam’s puberty blocker treatment.

Note. (A) Pregnancy Rate, (B) Days to Pregnancy Detection, (C) Pups per Litter, (D) Pup Mass at 25-days old, (E) Pup Survival Curve, Control (n=6), PB: Puberty Blocker (n=6). *p< .05.

4. Discussion

The puberty blocking GnRHa treatment resulted in a significant delay in the development of reproductive organ mass and morphology in young female rats; however, this developmental delay caused by GnRHa treatment was reversible following 4 weeks of drug withdrawal. Fertility of young female rats also returned after PB withdrawal with some reproductive disturbance. The reversable reproductive effects of GnRHa treatment are supported by previous research in adult rats [9].

The delayed development of the uterus and ovary caused by the puberty blocker was reversible after 4 weeks of withdrawal. Previous research on GnRHa treatment in adult rats has also demonstrated significant developmental delay of the ovaries and uteri, which returned to normal after drug withdrawal [9]. The morphology of the uterus was altered by 4 weeks of GnRHa treatment. The myometrial and endometrial lining of the uterus both suffered significant developmental delay in the PB group, which both recovered after 4 weeks of PB withdrawal.

The morphology of the ovaries indicates a significant disruption of follicular development caused by PB treatment. The number of early staged primary follicles was substantially greater in the PB group when compared to the control groups. Follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and estrogen production were likely inhibited by GnRHa treatment which resulted in an accumulation of primary and secondary follicles in the PB group due to fewer follicles being recruited to tertiary follicles. After 4 weeks of GnRHa withdrawal (PB-W), the number of primary follicles returned to the numbers seen in the control. Once the puberty blocker was removed, FSH likely returned to control concentration leading to greater follicular development and fewer primary follicles in the PB-W group.

There was a trend toward a greater number of secondary follicles in the PB group; however, this did not reach significance. The development from primary to secondary follicles is independent of FSH which would explain the greater number of secondary follicles in the PB group [12]. There were fewer tertiary follicles in the PB group compared to the control groups, but it did not reach statistical significance. The PB withdrawal had a similar number of tertiary follicles as the control groups indicating recovery from treatment. The arrest of follicular development caused by 4 weeks of GnRHa treatment was reversible in young female rats. The morphology changes of the ovary demonstrated in this study are supported by previous research in adult rats revealing GnRHa treatment can result in a greater number of small primary follicles and fewer larger more mature tertiary follicles [10].

The PB group had fewer corpora lutea than control animals, but it was not statistically significant. It was surprising to find any corpora lutea present in the PB group if LH was suppressed before puberty; however, the corpus luteum can develop in Sprague Dawley rats as young as 4-weeks old [13]. Therefore, the rats treated with the GnRHa could have been releasing some LH before 4-weeks of age leading to corpora lutea development. Additionally, treatment with a GnRHa initially triggers a flare effect of LH and FSH that could also explain the development of corpora lutea [5].

The H&E stained sections of ovarian corpora lutea from the PB group had a visual disruption of the luteal cells. Healthy development of the luteal cells is dependent on LH which was suppressed in the PB group. Following GnRHa withdrawal, the visual disruption of luteal cells appeared similar to control, implying recovery of corpora lutea morphology. Interruption of typical corpora lutea development identified in this study is in consensus with previous research reporting atrophy of the corpus luteum in rats undergoing GnRHa treatment [9].

Treatment of young female rats with a GnRHa for 4-weeks, did not significantly impact pregnancy rate following withdrawal of the drug and pairing with a fertile male. The limited number of rats breed and lack of statistical power is a significant limitation for the reproductive function results. Future research needs to clarify the minor reproductive disturbance found and monitor estrous cycles. The recuperation of reproductive function after GnRHa cessation is supported by previous research in adult rats [9,14]. Young female rats recovering from GnRHa treatment had an 83% pregnancy rate compared to 100% for controls. The 17% reduction in pregnancy rate caused by previous GnRHa treatment raises some fertility concerns that may have reached significance with a larger samples size. A majority of the rats previously treated with the GnRHa achieved pregnancy within 5-7 days of drug withdrawal and pairing with a sexually mature male. However, one rat was exposed to a sexually mature male for 42 days without pregnancy indicating reproductive function was disrupted by the earlier GnRHa treatment.

Two of the six previously GnRHa treated rats had difficulty achieving pregnancy (either delayed pregnancy or no pregnancy). Four of the GnRHa treated rats gave birth to healthy pups within 28-days of drug withdrawal and pairing with a fertile male. This was similar to all six control rats which gave birth to healthy pups within 26-days of placebo withdrawal and pairing with a fertile male. The majority of the puberty blocked rats only had a minor delay in pregnancy caused by the PB treatment. One of the PB rats had a more substantial delay in pregnancy of 35-days after drug withdrawal. Reproductive function may require a longer withdrawal period before returning in some individuals. A male was introduced the first day of GnRHa cessation, providing little time for the reproductive organs to mature. Future research should explore if an extended GnRHa withdrawal period would have an impact on pregnancy rate in young female rats.

Treatment with the GnRHa significantly delayed the number of days until pregnancy detection and number of days until giving birth. A delay in pregnancy was anticipated due to reproductive organs not maturing while taking the puberty blocker. The short one to two day delay in pregnancy of 67% of the GnRHa treated rats implies rapid recovery of reproductive function after drug withdrawal. The remaining 33% of GnRHa treated rats struggled to recover fertility after withdrawal. The recovery of reproductive function suggests some individual variation after GnRHa cessation in young female rats. The reproductive recovery problems demonstrated in some of the GnRHa treated rats warrants further investigation with a greater sample size. Mitigating any possible negative consequences of GnRHa therapy on fertility is an important factor to consider while supporting the health and wellbeing of transgender individuals. The reproductive results need to be replicated due to the small sample size to validate full reproductive recovery after withdrawal.

The number of pups per litter was altered following 4-weeks of GnRHa treatment. The six control rats gave birth to an average of 11 ± 2 pups, while the young female rats recovering from GnRHa treatment gave birth to an average of 7 ± 3 pups. The reduction in number of pups per litter suggests reproductive function had not recovered fully after GnRHa withdrawal. It was hypothesized that the immature uteri in the PB animals observed decreased the number of pups per litter. The fewer number of ovulating follicles in the PB animals could have also decreased the number of pups.

No gross physical abnormalities were observed in any of the pups. The blocking of puberty with a GnRHa in young female rats had no detectable impact on the health of the pups. This is in agreement with research in adult rats previously treated with a GnRHa which also gave birth to healthy pups after drug withdrawal [9]. Future research should investigate the influence of a longer recuperation time following GnRHa withdrawal and its impact on reproductive outcomes.

The survival rate of the pups was not influenced by previous GnRHa treatment. Young female rats recovering from GnRHa treatment had 57% of their litter survive through the entire intervention, while the control rats had 69% of their litter survive. The majority of these pups died within 5 days of giving birth in both groups. It was unclear if the dam’s nurturing behavior influenced the pup survival rate. All visual and behavioral observations indicate both groups had a typical gestation period and gave birth to healthy pups.

This study demonstrates that GnRHa treatment may have a minor impact on reproductive performance immediately following withdrawal. The pregnancy rate was not significantly different between young female rats treated with GnRHa and controls. The animals treated with GnRHa had delayed pregnancies but only for one to two days in most puberty blocked animals. Two of the six GnRHa treated rats had difficulty achieving pregnancy following drug withdrawal. The reduced litter size in GnRHa treated rats suggests reproductive difficulties that will require further investigation. The disruption of reproductive tract development and fertility caused by GnRHa treatment appears to be reversible in young female rats.

5. Conclusion

Young female rats treated with a puberty blocker (Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone agonist) for 4-weeks resulted in developmental delay of the reproductive organs, which recovered after withdrawal. A minor disruption in reproductive function was detected following withdrawal. This suggests a rapid recovery of reproductive morphology and function following puberty blocker withdrawal in young female rats. The minor pregnancy issue in some rats needs to be further investigated with a greater sample size to fully support reproductive function recovery. This information aims to help transgender youth understand the effects of medical treatment including blocking puberty on future reproductive health.

Conflicts of Interests:

The authors have no conflict of interest to disclose. There are no financial or ethical conflicts of interest in the manuscript.

Acknowledgement:

The authors would like to thank the support from the animal facilities at the University of Northern Colorado and student research assistance.

Ethical Disclosure:

The research procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Northern Colorado (2001-DH-R-23) and was in compliance with the Animal Welfare Act.

Contributions:

Brandon Jones PhD. (Conceptualization, methodology development, data collection, data analysis, and primary writer. David Hydock PhD.(Conceptualization, methodology development, data analysis, editing). All reviewed the manuscript and approved the version to be published

References

- Bishop A, Overcash F, McGuire J, et al. Diet and Physical Activity Behaviors Among Adolescent Transgender Students: School Survey Results. J Adolesc Health 66 (2020): 484-90.

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL. A Systematic Review of the Effects of Hormone Therapy on Psychological Functioning and Quality of Life in Transgender Individuals. Transgend Health 1 (2016): 21-31.

- Hembree WC, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Gooren L, et al. Endocrine Treatment of Gender-Dysphoric/Gender-Incongruent Persons: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. Endocr Pract 23 (2017):1437.

- Roger M, Chaussain JL, Berlier P, et al. Long Term Treatment of Male and Female Precocious Puberty by Periodic Administration of a Long-Acting Preparation of D-Trp6-Luteinizing Hormone-Releasing Hormone Microcapsules. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 62 (1986): 670-7.

- Gonen Y, Balakier H, Powell W, et al. Use of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist to Trigger Follicular Maturation for In-Vitro Fertilization. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 71 (1990): 918-22.

- Schagen SE, Cohen-Kettenis PT, Delemarre-van de Waal HA, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Agonist Treatment to Suppress Puberty in Gender Dysphoric Adolescents. J Sex Med 13 (2016): 1125-32.

- Torng PL, Pan SP, Hsu HC, et al. GnRHa before Single-port Laparoscopic Hysterectomy in a Large Barrel-Shaped Uterus. JSLS (2019): 23.

- Pasquino AM, Pucarelli I, Accardo F, et al. Long-term Observation of 87 Girls with Idiopathic Central Precocious Puberty Treated with Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone Analogs: Impact on Adult Height, Body Mass Index, Bone Mineral Content, and Reproductive Function. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93 (2008): 190-5.

- Johnson ES, Gendrich RL, White WF. Delay of Puberty and Inhibition of Reproductive Processes in the Rat by a Gonadotropin-releasing Hormone Agonist analog. Fertil Steril 27 (1976): 853-60.

- Ataya K, Tadros M, Ramahi A. Gonadotropin-releasing Hormone Agonist Inhibits Physiologic Ovarian Follicular Loss in Rats. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 121 (1989): 55-60.

- Hagen CP, Sørensen K, Anderson RA, Juul A. Serum levels of Antimüllerian Hormone in early maturing girls before, during, and after suppression with GnRH agonist. Fertil Steril 98 (2012): 1326-30.

- Lunenfeld B, et al. Insler V. Follicular Development and its Control. Gynecol Endocrinol 7 (1993): 285-91.

- Picut CA, Remick AK, Asakawa MG, et al. Histologic Features of Prepubertal and Pubertal Reproductive Development in Female Sprague-Dawley rats. Toxicol Pathol 42 (2014): 403-13.

- Lehrer SB, Tekeli S, Fort FL, et al. Effects of a GnRH agonist on fertility following administration to prepubertal male and female rats. Fundam Appl Toxicol 19 (1992): 101-8.

- Gorzek JF, Hendrickson KC, Forstner JP, et al. Estradiol and Tamoxifen reverse Ovariectomy-induced Physical Inactivity in Mice. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39 (2007): 248-56.

- Olson-Kennedy J, Chan YM, Garofalo R, et al. Impact of Early Medical Treatment for Transgender Youth: Protocol for the Longitudinal, Observational Trans Youth Care Study. JMIR Res Protoc 8 (2019): e14434

Impact Factor: * 5.8

Impact Factor: * 5.8 Acceptance Rate: 71.20%

Acceptance Rate: 71.20%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks