Cardiovascular Outcomes and Potential Treatment Options in COVID-19 Patients: Role of Inflammation and Cytokine Storm: A Brief Review

Muhammad Waqas Nasir, Yong Gao*

The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, 230001, China

Muhammad Waqas Nasir ORCID ID: 0000-0001-7478-5486

Yong Gao ORCID ID: 0000-0001-6352-8652

*Corresponding author: Yong Gao, The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, 230001, China.

Received: 05 December 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Published: 16 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Muhammad Waqas Nasir, Yong Gao. Cardiovascular Outcomes and Potential Treatment Options in COVID-19 Patients: Role of Inflammation and Cytokine Storm: A Brief Review. Archives of Microbiology and Immunology. 9 (2025): 260-275.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), has rapidly evolved into a global pandemic, resulting in more than 770 million confirmed cases and over 7 million deaths worldwide to date. A substantial proportion of COVID-19 related deaths are linked to cardiovascular complications, either as pre-existing co-morbidities or as newly developed manifestations during infection. Evidence suggests that cardiovascular risk factors, rather than established cardiovascular disease itself, play a greater role in adverse outcomes among critically ill patients. Moreover, myocardial injury has been frequently reported in COVID-19, occurring independently of pre-existing cardiovascular conditions, and is primarily associated with systemic inflammation and multiorgan damage. In severe cases, pathological mechanisms such as cytokine storm, lymphopenia, and elevated cardiac biomarkers (particularly cardiac troponin) contribute to cardiovascular dysfunction. The cytokine storm, in particular, drives cytokine release syndrome (CRS), exacerbating myocardial injury and increasing mortality. Recent data indicate that the incidence of myocardial injury is approximately 7% among SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals, underscoring its clinical significance. This review highlights the central role of inflammation in COVID-19 associated cardiovascular complications, including myocardial injury, thrombosis, and vascular dysfunction. By summarizing current evidence, we aim to provide insights into underlying mechanisms and propose considerations for optimizing cardiovascular care in COVID-19 patients.

Keywords

COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2, Inflammation, Cytokine storm, Cardiovascular dysfunction, Myocardial injury

COVID-19 articles, SARS-CoV-2 articles, Inflammation articles, Cytokine storm articles, Cardiovascular dysfunction articles, Myocardial injury articles

Article Details

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging infectious disease caused by the novel severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Beta coronavirus genus within the Coronaviridae family [1]. COVID-19’s impact on the cardiovascular system arises from a complex interplay of direct viral injury and indirect systemic responses. A key entry point is the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), the cell-surface receptor for SARS-CoV-2. ACE2 is expressed not only in the lungs but also in heart tissue – including cardiomyocytes, vascular endothelial cells, and especially pericytes that support microvasculature[2]. This broad ACE2 distribution provides multiple portals for the virus to invade cardiovascular cells. Binding of the viral spike protein to ACE2 triggers internalization of the complex, which reduces ACE2 activity and in turn upregulates the renin–angiotensin–aldosterone system (RAAS) (elevating angiotensin II while diminishing its counter-regulator Ang-(1-7)). The resultant RAAS imbalance leads to vasoconstriction and heightened inflammation[3], setting the stage for cardiovascular damage in COVID-19. Once inside cardiac cells, the virus can directly injure the myocardium. SARS-CoV-2 has been detected in heart tissue and can infect cardiomyocytes via ACE2, causing viral myocarditis with myocyte death and impaired contractility[4]. Infected cardiomyocytes lose their normal structure and function, which may precipitate acute cardiac injury, pump failure, and arrhythmogenic disturbances (e.g. atrial fibrillation or ventricular tachyarrhythmias). Similarly, pericyte infection disrupts microvascular support, potentially leading to local ischemia or fibrosis. Notably, patients with upregulated cardiac ACE2 (such as those with heart failure) may be especially susceptible to direct viral myocardial involvement [5]. In addition to direct cytopathic effects, the loss of ACE2 on cardiac cells further deprives the heart of its usual protective mechanisms (since ACE2 normally generates vasodilatory, anti-fibrotic peptides), exacerbating the injury. Another central element is endothelial dysfunction (Figure 1). Vascular endothelial cells, which line blood vessels, can also be affected by SARS-CoV-2. Endothelial cells, once infected or exposed to viral particles, exhibit an inflammatory phenotype and can undergo apoptosis, compromising the integrity of the vessel wall [6]. Autopsy studies in COVID-19 have revealed endotheliitis active inflammation and viral inclusions within endothelial cells of multiple organs. The damaged endothelium loses its ability to regulate vascular tone and permeability, tending toward vasoconstriction and increased vascular leak. Moreover, endothelial injury shifts the hemostatic balance towards a pro-thrombotic state: injured endothelial cells downregulate anti-coagulant signals and upregulate adhesion molecules and tissue factor, promoting platelet aggregation and coagulation [7]. This prothrombotic milieu, in conjunction with virus-induced platelet activation and dysregulated coagulation cascades, underlies the high incidence of thromboembolic events observed in severe COVID-19. In fact, widespread endothelial damage and inflammation can trigger disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and micro thromboses in the microcirculation, contributing to organ ischemia[8]. Clinically, this manifests as an increased risk of deep vein thromboses, pulmonary emboli, ischemic strokes, and even acute coronary syndromes in COVID-19 patients. Systemic hypoxia further aggravates cardiovascular stress in severe COVID-19. When the lungs are compromised (e.g. in pneumonia or acute respiratory distress syndrome), reduced oxygenation leads to tissue hypoxemia. The heart must then pump harder to deliver oxygen to tissues, increasing myocardial oxygen demand even as oxygen supply is limited. This supply-demand mismatch can precipitate ischemia, especially in individuals with pre-existing coronary artery disease or atherosclerotic plaques[9]. In COVID-19, hypoxemic pulmonary vasoconstriction and acute pulmonary hypertension may place a sudden pressure burden on the right ventricle, occasionally resulting in acute cor pulmonale or right heart strain. Consequently, respiratory failure can indirectly overload the cardiovascular system, unmasking subclinical heart disease and precipitating overt ischemia or infarction. Another consequence of severe infection is oxidative stress. The hyperinflammatory state in COVID-19 generates excess reactive oxygen species (ROS) that damage cellular components. In the heart and vessels, oxidative stress injures mitochondria the powerhouses of cardiomyocytes impairing ATP production and contractility[10]. Oxidative damage to the endothelium further amplifies vascular dysfunction. SARS-CoV-2 itself can stimulate ROS production; for example, it activates NADPH oxidase in endothelial cells, leading to superoxide generation and mitochondrial injury. This oxidative milieu not only harms cells but can also enhance viral entry (oxidation of certain thiol groups can favor spike-ACE2 binding), creating a vicious cycle of infection and injury. Antioxidant mechanisms are thus overwhelmed, contributing to myocardial cell death and vascular inflammation[11].

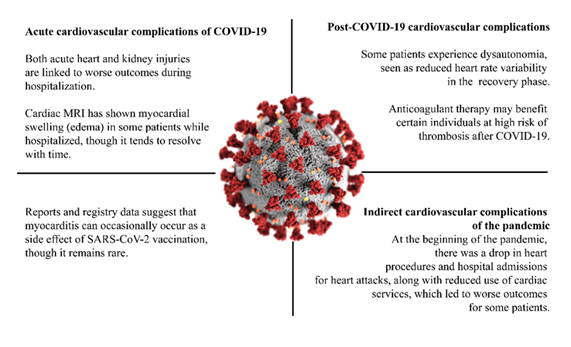

Acute complications include myocardial injury, edema observed by cardiac MRI, and acute kidney injury, all associated with worse in-hospital outcomes. Post-COVID-19 complications may involve dysautonomia (reduced heart rate variability) and increased thrombotic risk, for which anticoagulant therapy may be beneficial in selected patients. Vaccination-associated effects such as myocarditis are rare but have been reported in registry data. Indirect complications of the pandemic include reduced hospital admissions and cardiac procedures during the early phase of the pandemic, which contributed to worse outcomes for some patients.

A hallmark of severe COVID-19 is the cytokine storm an excessive immune response with elevated levels of inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). This hypercytokinemia has profound cardiovascular effects. The flood of cytokines triggers further inflammation in the heart and vessels, often exacerbating the myocarditis and endothelial dysfunction described above. For instance, IL-6 levels are significantly higher in COVID-19 patients who exhibit myocardial injury [12–14]. These cytokines can depress myocardial contractility (akin to septic cardiomyopathy), induce vasodilation or capillary leak, and promote coagulopathy. TNF-α and IL-1β, in particular, are known to impair cardiac contractile function and can destabilize atherosclerotic plaques, potentially precipitating acute coronary syndromes. Additionally, cytokine-driven inflammation further activates the endothelium and platelets, compounding the pro-thrombotic state. In essence, the immune overreaction becomes a secondary hit on the cardiovascular system: the so-called “cytokine storm” amplifies tissue damage and can lead to multi-organ failure. Clinically, this is associated with shock, including cardiogenic shock, in some critically ill patients – a state often driven by a combination of myocardial depression and systemic vasodilation due to overwhelming inflammation. Collectively, these interrelated mechanisms culminate in significant cardiovascular morbidity in COVID-19 patients. Acute cardiac injury, evidenced by elevated cardiac troponin levels, occurs in roughly 1 out of 5 hospitalized COVID-19 patients and is associated with worse prognosis[15,16]. Many patients develop arrhythmias, ranging from benign arrhythmias to malignant arrhythmias, as inflammation and metabolic stress alter the cardiac electrophysiology. Myocarditis, whether viral or immune-mediated, has been reported in COVID-19 and can progress to acute or even fulminant heart failure. In addition, some patients demonstrate stress-induced cardiomyopathy, further compromising cardiac function. Heart failure may arise de novo in previously healthy individuals or represent acute decompensation of pre-existing disease, triggered by the systemic burden of infection and inflammation. Beyond direct myocardial injury, thromboembolic complications are also prominent. Venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism) and arterial thromboses leading to stroke or myocardial infarction are frequently observed, reflecting the combined effects of endothelial injury, cytokine-driven coagulopathy, and platelet activation. Together, these mechanisms highlight the intricate interplay between inflammation, myocardial injury, and thrombotic events in driving cardiovascular complications in COVID-19 [17,18]. In summary, COVID-19 acts on the cardiovascular system through multiple converging pathways (direct viral cytotoxicity, endothelial injury, inflammation/cytokine storm, coagulopathy, and hypoxic stress), which together explain the diverse cardiac manifestations observed in infected patients. This pathophysiologic understanding underscores why patients with COVID-19 especially those with pre-existing cardiovascular conditions – require careful cardiac monitoring and why therapies aimed at modulating inflammation, coagulation, and myocardial stress are key in managing severe cases.

Pathophysiology of Cardiovascular Involvement in COVID-19

SARS-CoV-2 exerts cardiovascular effects through both direct viral injury and indirect systemic responses. A pivotal factor is the virus’s use of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) as its cellular receptor. ACE2 is abundantly expressed in the heart (notably on cardiomyocytes and pericytes) and in vascular endothelium. When the virus binds to ACE2 to enter these cells, it can injure or kill them, potentially causing myocarditis (inflammatory injury of heart muscle) and impairing cardiac contractility or electrical stability[19]. Viral particles and RNA have been detected in cardiomyocytes of infected animal models and in occasional human cases, supporting that direct myocardial infection can occur. However, such direct cardiac infection is often short-lived and only a minority of COVID-19 patients develop fulminant viral myocarditis. More commonly, myocardial injury in COVID-19 arises from indirect mechanisms rather than widespread virus-induced myocyte destruction[20]. One consequence of viral ACE2 binding is the disruption of the renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS). ACE2 normally helps degrade angiotensin II (Ang II) into angiotensin-(1-7), a peptide that promotes vasodilation and anti-inflammatory effects. SARS-CoV-2-mediated downregulation of ACE2 activity can lead to excess Ang II and diminished angiotensin-(1-7), tilting the balance toward vasoconstriction, inflammation, thrombosis, and fibrosis. Indeed, studies have found markedly elevated Ang II levels in patients with severe COVID-19, correlating with viral load and lung injury. This Ang II/AT1-receptor overactivation likely exacerbates endothelial and cardiac damage by inducing oxidative stress, inflammatory signaling, and microvascular constriction (Figure 2). Widespread endothelial dysfunction is a hallmark of severe COVID-19 and a major contributor to its cardiovascular complications. Endothelial cells lining of the blood vessels can be directly infected by SARS-CoV-2 or, more often, indirectly injured by the intense inflammatory milieu (the “cytokine storm”). Once activated or damaged, the endothelium loses its normal anti-thrombotic and vasodilatory properties, resulting in unchecked vasoconstriction, increased vascular permeability, and a pro-thrombotic tendency. Indeed, COVID-19 is increasingly recognized as not merely a respiratory illness but also an endothelial disease affecting the pan-vasculature[21].

Endothelial injury, combined with abnormal blood flow and hypercoagulability, fulfills Virchow’s triad for thrombogenesis in COVID-19, which helps explain the high incidence of thromboembolic complications in severe cases. Autopsy studies confirm disseminated intravascular thrombosis: in one series of 40 COVID-19 fatalities, 35% showed cardiac myocyte necrosis, and of those, the vast majority had only scattered focal necrosis (microinfarcts) rather than a single large infarction[22]. Fibrin-rich microthrombi have been found within myocardial capillaries, often without completely occluding the larger coronary arteries. This microvascular clotting, along with direct pericyte loss (pericytes are capillary support cells), can cause patchy myocardial ischemia and contribute to acute cardiac injury. Furthermore, endothelial dysfunction entails reduced nitric oxide availability and shedding of the protective endothelial glycocalyx (e.g. loss of heparan sulfate), changes that promote vasoconstriction and coagulation. The net effect is a high risk of myocardial infarctions (often secondary to oxygen supply–demand imbalance) and diffuse myocardial damage despite no acute plaque rupture[23]. The hyperinflammatory response (“cytokine storm”) in COVID-19 amplifies cardiovascular damage through multiple pathways. Excess cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6), IL-1β, and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) induce a state of systemic inflammation that can depress myocardial function and disrupt vascular homeostasis. In particular, TNF-α and other inflammatory mediators released in severe COVID-19 degrade endothelial nitric oxide synthase and reduce nitric oxide production, while also directly increasing microvascular tone[24]. High levels of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated during this hyperinflammatory state, leading to oxidative stress that injures cardiac myocyte mitochondria and further damages the endothelium. Such oxidative injury to mitochondria impairs ATP production in cardiomyocytes and can precipitate arrhythmias or acute heart failure. Inflammatory cytokines also promote coagulopathy: for example, IL-6 drives up fibrinogen levels and, together with tissue factor released from damaged cells, contribute to excessive clotting. Thus, the cytokine storm creates a vicious cycle of inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, and thrombosis, compounding the direct viral effects on the cardiovascular system [25].

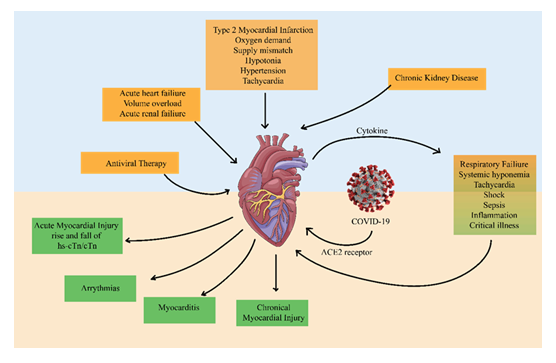

SARS-CoV-2 infection initiates myocardial damage through ACE2 receptor binding, cytokine release, systemic hypoxemia, and inflammation. These mechanisms contribute to acute myocardial injury, arrhythmias, myocarditis, chronic myocardial injury, and heart failure. Systemic complications, such as acute renal failure, chronic kidney disease, and respiratory failure, further aggravate cardiovascular stress. The figure highlights the interconnected pathways driving cardiovascular morbidity in COVID-19.

Severe respiratory involvement in COVID-19 (e.g. acute respiratory distress syndrome) adds further stress through systemic hypoxemia and heightened adrenergic drive. Prolonged hypoxia triggers an increase in cardiac output (tachycardia) and can precipitate ischemia, especially in patients with underlying coronary artery disease who cannot meet the elevated oxygen demand. Fever and sympathetic over-activation during critical illness also raise myocardial oxygen demand while oxygen supply is compromised, leading to an oxygen supply–demand mismatch in the heart. This mechanism (a type 2 myocardial infarction due to demand ischemia) likely underlies some of the cardiac troponin elevations observed in COVID-19 patients without direct coronary plaque rupture. Indeed, acute myocardial injury – defined by elevated cardiac troponin – is common in hospitalized COVID-19 patients (reported in ~10–35%) and is strongly associated with worse outcomes. The combination of hypoxic stress, microthrombi, and hyperinflammation can culminate in acute heart failure or arrhythmias in susceptible individuals [26,27].

Pulmonary Involvement in COVID-19

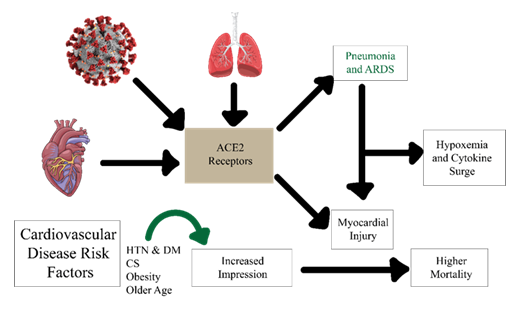

The function of the lungs, an important target organ of the SARS-Cov-2 infection, is severely impaired. Common clinical manifestations of late-stage COVID-19 include shortness of breath, pneumonia-like symptoms and hypoxia, which is ultimately fatal to patients. SARS-CoV-2 enters the pulmonary vessels via endocytosis and activates ADAM(a disintegrin and metalloproteinase) metallopeptidase domain 17 (ADAM17), which in turn cleaves ACE2, indicating loss of protection against the renin-system angiotensin-aldosterone “RAAS”[28], which is mediated by cleaved ACE2. ADAM17 activation also triggers acute pneumonia and infiltration of cytokines and leukocytes into the alveolar space, resulting in pulmonary edema. Cytokine storm is the result of hyperactive systemic inflammation in response to COVID-19 infection. This storm causes respiratory problems and is responsible for most deaths in the final stages of treatment [29]. Lung complications associated with COVID-19 include acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), vascular endotheliitis, sepsis, pulmonary edema, and pulmonary embolism. Two percent experience serious pulmonary complications after surgery, with most deaths mainly due to pulmonary embolism. Lung autopsy reports from COVID-19 patients who died from ARDS showed severe alveolar damage and perivascular T-cell infiltration. Histological analysis also showed increased thrombus formation, intussusceptive angiogenesis and microangiopathy in patients with COVID-19 compared to influenza[30]. Gene expression analysis using RNA isolated from COVID-19 patients revealed multiple inflammatory markers and angiogenesis-related genes were differentially regulated compared to healthy lungs. Importantly, there were significantly higher positive numbers of ACE2 in COVID-19 tissues compared to control. COVID-19 patients with ARDS were also characterized by increased fibrin deposition and high expression of D-dimers and fibrinogen, suggesting that fibrinolysis is a mortality factor[31]. Although pulmonary problem is the dominant scientific manifestation of COVID-19, underlying cardiovascular headaches and acute cardiac damage decorate the patient’s vulnerability. Acute respiration problem/failure and cytokine hurricane may also purpose decreased oxygen supply, main to acute myocardial damage in COVID-19 patients (Figure 3). Diverse cardiovascular manifestations and COVID-19 several experimental and clinical studies of viral infections, including influenza and other severe inflammatory syndromes, have demonstrated that patients with underlying coronary artery disease (CAD) or atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) are at significantly higher risk of developing adverse outcomes during systemic infections[32]. Patients with pre-existing cardiovascular diseases may be particularly vulnerable to ischemic events triggered by systemic inflammation and oxygen supply–demand mismatch, underscoring the complex interplay between infection, inflammation, and cardiac pathology[33].

Figure 3: Mechanistic overview of ACE2 receptor–mediated cardiovascular involvement in COVID-19. SARS-CoV-2 binds to ACE2 receptors in the lungs, heart, and vascular system, triggering pneumonia/ARDS, cytokine release, and myocardial injury. Pre-existing risk factors such as hypertension (HTN), diabetes mellitus (DM), obesity, and older age enhance susceptibility. The downstream effects of hypoxemia, systemic inflammation, and myocardial damage culminate in higher mortality among COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular comorbidities.

Table 1: Cardiovascular abnormalities during COVID-19 disease

|

Manifestation |

Potential Mechanism |

Incidence/Prevalence |

Reference |

|

Severe coronary events (ACS/MI) |

Plaque rupture due to systemic inflammation and increased shear stress; microvascular dysfunction; hypercoagulability; endothelial dysfunction aggravating pre-existing CAD |

Rare overall, but reported; up to 7–8% in hospitalized patients with CV risk factors |

[34] |

|

Serious cardiac injury (↑ troponin, myocarditis-like injury) |

Direct viral entry (ACE2-mediated myocardial dysfunction), systemic inflammation, MOD supply-demand mismatch, micro thrombosis, iatrogenic drug injury |

8–12% on average; up to 20–30% in critically ill; higher in deceased patients |

[35] |

|

Heart failure (acute or decompensated) |

Consequence of myocardial injury, inflammation, arrhythmia, increased metabolic demand; cytokine storm and hypoxemia aggravating pre-existing HF |

Reported in 23–52% of deceased; ~12% among survivors in early studies; pooled prevalence ~20% in hospitalized cohorts |

[36] |

|

Arrhythmia (tachy- or bradyarrhythmias, AF, VT, conduction block) |

Myocardial injury, hypoxia, electrolyte imbalance, systemic inflammation, QT-prolonging drugs (e.g., HCQ/azithromycin, lopinavir/ritonavir), myocarditis |

16–20% overall; up to 44% in severe/ICU cases; atrial fibrillation most common; malignant ventricular arrhythmias less frequent |

[37] |

|

Thromboembolic complications (VTE, PE, arterial thrombosis) |

Endothelial injury, platelet activation, cytokine-driven coagulopathy (COVID-19–associated coagulopathy) |

VTE in 20–30% of ICU patients; arterial thrombosis ~3–5% |

[38] |

|

Myocarditis / Myopericarditis |

Direct viral infiltration of myocytes (ACE2), immune-mediated injury, microvascular inflammation |

Clinical diagnosis uncommon (<2%), but cardiac MRI studies show subclinical myocarditis-like changes in up to 30–40% post-infection |

[39] |

|

Stress (Takotsubo) cardiomyopathy |

Catecholamine surge, systemic stress, microvascular dysfunction |

Rare; case reports and small series; ~1–2% among hospitalized COVID-19 with chest pain syndromes |

[40] |

|

Long-term consequences (“Long-COVID CV sequelae”) |

Persistent myocardial inflammation, endothelial dysfunction, autonomic imbalance, dysregulated lipid/glucose metabolism |

~10–30% of post-acute COVID-19 patients report palpitations, chest pain, or POTS-like symptoms; MRI shows persistent scar/inflammation in a subset |

[41] |

|

Sudden cardiac death (rare, severe cases) |

Malignant ventricular arrhythmias, severe myocarditis, massive thrombosis, drug-induced QT prolongation |

Rare, usually in severe/critically ill with underlying risk factors |

[42] |

COVID-19 patients experience lethargy (20-40%), cough (50%), fever (80-90%), and diarrhoea as leading symptoms. COVID-19 patients are considered at high risk for poor outcomes if they have a history of cardiovascular disease (CVD). Among 4,248 COVID-19 patients, 39.7% were diagnosed with acute cardiac injury (ACI), with 93% of these cases occurring on or after hospital admission. Compared to patients without ACI, those with ACI had a mortality rate of 95% (risk ratio 4.45), and among survivors, 38.7% were re-admitted within an average of 2.5 months, while 44.9% of those recovered from ACI required re-hospitalization. [103,104]. The ratio of death is greater in older ages, and patients older than 50 years, 50- 59 years, 60-69 years, 70-79 years and over 80 years have mortality rates <0.5%, 2%, 4%, 8%, and 16% respectively. The binding affinity of SAR-CoV-2 S protein to ACE2 is 10 to 20 times greater than SARS protein, representing that SARS-CoV-2 person-to-person transmission might be more readily. In COVID-19 patients, the virus of SARS-CoV-2 follows different pathways to cause infection. The infection is also linked with Kawasaki disease development, especially in children, as demonstrated by several studies[43]. In the patients having underlying heart disease with cardiac insufficiency, infection of SARS-CoV-2 might respond by triggering issues for the degradation of the condition and possibly cause death.

Myocardial Injury and COVID-19

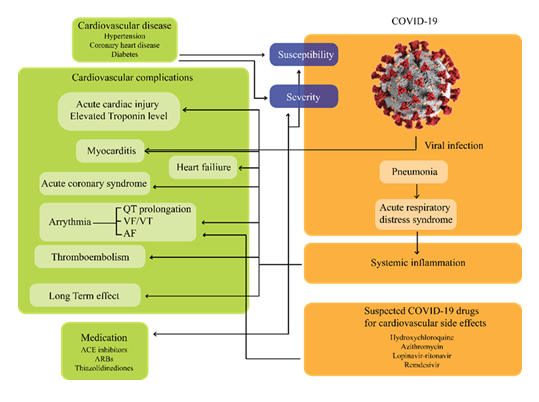

The COVID-19 patients with already existing stress cardiomyopathy, acute myocardial infarction, non-specific myocardial injury, coronary spasm, and non-ischemic cardiomyopathy showed complex cardiovascular manifestations. COVID-19 individuals with severe disease experience acute heart injury and cardiac co-morbidity. The examination of 1527 COVID-19 patients in Wuhan, China showed 16.4% cerebrovascular and cardiac disease, 9.7% diabetes, and 17.1 % hypertension; sub-group analysis indicated 16.7% of cases of cardiac-related conditions were in ICU, whereas 6.2% of cases were non-ICU. The relationship between SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 changes ACE2 signaling pathways and causes lung injury and myocardial injury [44,45]. The target cardiac cells of SARS-CoV-2 might be pericytes with high expression ACE2. The histological study of 5 out of 16 patients showed viral replication in both tissues. The viral infection causes pericyte injury, and this injury contributes to microvascular dysfunction and capillary endothelial cell dysfunction. Furthermore, the cytokine storm attack on different organs could result in multiorgan failure, including heart failure. Type I acute coronary events, plaque disruption, vascular endothelial dysfunction, cytokine storm, and increased stress cardiomyopathy contribute to SARS-CoV-2 infection-related myocarditis. Increased cytokine levels in infected individuals may participate in endothelial dysfunction, myocardial injury, micro thrombogenesis, and coronary plaque destabilization[46]. The 187 confirmed COVID-19 patients study reported that 27% of cases showed myocardial dysfunction with consistently elevated levels of TnT (Troponin T). Non- specific or less myocardial biomarkers showed different change patterns, such as creatine kinase myocardial band (CK-MB) isoenzyme, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and creatine kinase (CK) that were also increased in COVID-19 patients with cardiovascular-related complications. Several studies reported that ICU-admitted older individuals with COVID-19 show elevated levels of LDH (lactate dehydrogenase)[47,48]. Cardiac arrhythmias, myocarditis, ACS (acute coronary syndrome), heart failure, and sudden deaths could all result from myocardium inflammation caused by the viral infection. Inflammatory response and myocardial risk increase due to the direct entrance of the SARS- CoV-2 virus into the blood vessels and myocardium. Inflammatory pathogenesis of myocardial injury during disease progression has been demonstrated to be positively linked with the levels of plasma C-reactive protein and troponin. COVID-19 with myocardial infarction confirmed the death rate of 1 in 5 patients, and 50% survival could be possible if the troponin levels could be measured routinely. Therefore, physicians should pay more attention to the abnormal immune response system and myocardial injuries in patients suffering from COVID-19 (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Interplay between cardiovascular comorbidities, COVID-19 infection, and therapeutic challenges. Patients with underlying cardiovascular disease (e.g., hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes) face heightened susceptibility and severity of COVID-19 outcomes. Viral entry via ACE2 receptors triggers pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and systemic inflammation, which in turn lead to myocardial injury, arrhythmia, thromboembolism, and heart failure. Cardiovascular complications are further influenced by the off-target effects of some COVID-19 therapies (e.g., hydroxychloroquine, azithromycin, lopinavir–ritonavir, remdesivir), highlighting the need for careful risk–benefit evaluation in management.

Myocardial injury and viral myocarditis can be considered the leading grounds of demises in COVID-19 patients. Furthermore, seriously ill patients experience decreased regulatory T-cells, pro-inflammatory T-cells, hyperactivation, and severe lymphopenia, which promotes disturbance in immune responses. The circulating T-cells in peripheral blood showed a significant reduction in SARS-CoV-2- infected individuals. Lymphopenia was reported in > 85% of infected patients. During early infection, the most significant finding is the reduction in CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes with a relative increase of macrophages. Laboratory tests of patients who died from COVID-19 showed over-activation of CD8 and CD4 lymphocytes. The CD8+ T-cells are considered the primary cytotoxic cells, and morbid cytotoxic T-cells in severe patients result from the hyper-action of CD4+ T-cells. While these diseased cytotoxic T-cells invade and eradicate the virus, they also cause lung and myocardial injury [49]. To summarize, abnormal immune response, ACE2-mediated viral infection, oxygen demand, and supply to the myocardium can be significant causes of myocardial injury and other cardiovascular complications in COVID-19 patients.

Thrombosis Outcomes in COVID-19 Patients

Seriously ill COVID-19 patients are at greater risk of both bleeding and thrombosis, whereas non-critical patients generally have a lower risk of significant bleeding and venous thromboembolism (VTE). Acute infection triggers a cytokine surge that activates cells within pre-existing atherosclerotic plaques, thereby increasing ischemic syndromes and thrombotic risk. Cytokine release syndrome (CRS) further disrupts coagulation pathways, promotes tissue and organ dysfunction, and reduces the activity of natural killer (NK) cells and T lymphocytes. Clinical evidence supports these observations: Wang et al. reported that 7 out of 11 patients admitted to the ICU experienced coagulation dysfunction. Extreme inflammation, prolonged immobilization, hypoxia, and disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) contribute significantly to arterial and venous thromboembolic complications in COVID-19. In addition, vascular inflammation promotes both macro- and micro-thrombosis, while systemic inflammation and circulating intravascular coagulation can precipitate pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis (DVT) [50,51]. Secretion of a colony-stimulating factor of granulocyte-macrophage (GM-CSF) from microvascular endothelial cells of human pulmonary followed lipopolysaccharides (LPS) as an inflammatory stimulus also plays a crucial role in acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) of acute type. Individuals who experienced ARDS also show elevated vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) levels that increase microvascular permeability by endothelial injury. Moreover, Renin-angiotensin system (RAS) induces an increased risk for pulmonary hypertension, embolism and cardiac fibrosis through the up-regulation of inflammation, vasoconstrictions, proliferation, and fibrosis events. This system also increases the concentrations of local angiotensin II and accelerates kidney and cardiac injury. Lymphopenia, prolonged coagulation profile, cardiac disease, and death could be the consequences of SARS-CoV-2 infection [52].

COVID-19, Inflammation, and Cytokine Storm

Cardiomyocyte necrosis could occur due to inflammation and virus-induced injury in response to local inflammation induced by cardiomyocyte infection. The study of 99 cases in Wuhan reported that 38% of patients had elevated levels of neutrophils. Neutrophils with viral particles indicate that the virus induces inflammation. The SARS-CoV-2 hematogenous spread to tissues and other organs could result in the infection of endocardium endothelial cells. Infection preferentially targets the inflammatory responses in the patients. The inflammatory process depends on the cytokines. Natural killer cells, macrophages, B and T-lymphocytes, dendritic cells and many other immune cells participate in the production of cytokines [53,54]. ARDS progression and development is directly concerned with inflammatory cytokine storm in COVID-19 patients experiencing increased levels of serum cytokines. This situation can promote secondary infection by disturbing the immune system to increase the condition of immunodeficiency. Extensive lung damage and pulmonary inflammation in SARS-CoV-2 infected individuals are related with raised levels of the, pro- inflammatory cytokines [e.g., inducible protein-10 (IP10), interleukin-12 (IL12), IL-6, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCPI), IL-1β, interferon-γ (IFNγ), inflammatory protein-1α of macrophage (MIP-1α), granulocyte colony- stimulating aspect (G-CSF), and tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α). Resultant inflammation and elevated circulating cytokine levels directly affect cardiomyocytes, which may lead to myocardial injury, endothelial dysfunction, atherogenesis, and endothelial cell function reprogramming. The vital cytokine GM-CSF initiates tissue inflammations produced by auto-reactive T-helper cells[55–57]. The inflammations initiate the organ injury (i.e., lungs) and show their deleterious effects by increasing inflammatory responses on other organs such as the heart. Increased inflammatory biomarkers correlate with electrocardiographic abnormalities and cardiac injury biomarkers. The inflammatory cytokines alter the role of many cardiomyocyte ion channels, including Ca++ and K+ channels and cause a prolonged ventricular action potential. These cytokines trigger serious arrhythmic events, especially in long QT Syndrome (LQTS) patients, by inducing hyperactivation of the CSS (cardiac sympathetic system) through peripheral and inflammatory reflex pathways [58,59]. Inflammatory and endothelial cell death occurs due to inflammatory cells with viral elements in the endothelial cells. These appearances support SARS- CoV-2 involvement in endothelitiitis induction in different organs due to host inflammatory responses and direct viral involvement.

Cytokine storms use well-characterized mechanisms to induce the development of endothelial dysfunction. The human endothelial cells increase adhesion molecule expression due to inflammatory cytokines; these cytokines also increase the release of IL-6 by stimulating human macrophages with oxidized LDLs (oxLDLs). Immune system abnormality associated with pathogenesis and infection severity in COVID-19 individuals has been confirmed by previous studies. A large amount of cytokines production (cytokine storm) due to virus infection may also cause vital organ injury by activating severe immune responses [60,61]. Viral particles attack the respiratory mucosa and invade other cells, causing critical complications in infected patients. Conversely, COVID-19 individuals also experience disease severity which correlates with the levels of interleukin-10 and interleukin-4. Cardiac demand increases due to an increase in cytokine activity and vascular plaque destabilization by systemic inflammation. The infection process of SARS-CoV-2 through ACE2 and its cardiomyocyte invasion, insufficient oxygen supply to the myocardium due to pulmonary infection, and cytokine storm syndrome all participate in cardiac injury[62]. The inflammation-based cardiac injury was reported in heart biopsy by observing mononuclear inflammatory infiltrates in the individuals infected with SARS-CoV-2, but the injury mechanism was uncertain. Cytokine release syndrome, hyper-inflammation, cardiac injury biomarkers elevation, and ARDS can all be used to characterize COVID-19 in the severe patients.

Effects of COVID-19 Therapeutic Drugs and the Cardiovascular System

The cytokine storm, main contributor in response to infection and bases the disease progression and severity by increasing expression levels of pro- inflammatory cytokines. Pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 can be activated and secreted in COVID-19 patients. The therapeutic effect of pro- inflammatory IL-1 and IL-6 family member suppression has been shown in several inflammatory diseases and viral infections. The cytokine system’s key member is IL-6 which plays a vital role in severe inflammation[63]. IL-6 inhibitors have a beneficial impact on the prognosis of COVID-19 disease. Tocilizumab (IL-6R antibody) treatment treats ARDS and hyper-inflammation in COVID-19 to reduce the disease activation potential biomarker IL-6. The anti-IL-6 targeted therapies (Sarilumab and tocilizumab, both are IL-6 receptors targeting monoclonal antibodies) not only improve the multiorgan dysfunction but also attenuate the high arrhythmia risk in severely ill COVID-19 patients[64]. Sarilumab and tocilizumab target the signaling pathways of IL-6, while Sarilumab shows higher efficiency than tocilizumab. Inspiring clinical results, including respiratory function improvement and patient temperature reduction, have demonstrated the effects of blockage of IL-6 receptors by tocilizumab. Treatment with tocilizumab helps to reduce mortality and inflammatory storm in severe COVID-19 patients[65]. Tocilizumab has been proven to be a new effective therapeutic strategy to decrease the seriousness of this fatal infectious disease. The trials of tocilizumab to check its impact on cytokine storm syndromes have been started. Besides the monoclonal antibodies, the emerging infection SARS-CoV-2 can also be prevented or controlled by several other options, including interferon therapies, vaccines, oligonucleotide-based therapies, peptides, and small-molecule drugs. To date, neither an anti-viral therapeutic agent nor vaccine has been permitted to cure any human CoV infection or COVID-19. Therefore, supportive care should be focused on coronavirus disease management. Different therapeutic drugs with possible outcomes have been used to control and prevent COVID-19, which provides a reference for advanced studies (Table 2).

Table 2: Effect and the mechanism of COVID-19 therapeutic drugs on cardiovascular (CV) Dysfunction.

Possible Treatment Options

Therapeutic strategies targeting hyperinflammation have shown promising results. IL-6 and IL-1 inhibitors such as tocilizumab, anakinra, and canakinumab mitigate cytokine storms and improve survival, although corticosteroids may increase the risk of secondary infections[87]. Interferon-α demonstrates antiviral activity by inhibiting SARS-CoV-2 replication in vitro, while bevacizumab is under trial for vascular protection. Traditional Chinese medicines (e.g., Shuang Huang Lian, tetrandrine, Lianhua Qingwen) also exhibit inhibitory effects on viral replication and cytokine release[88]. Colchicine, with established cardioprotective benefits in myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, and pericarditis, limits NLRP3 inflammasome activation and reduces pneumonia and myocardial necrosis in COVID-19 patients[89]. Ongoing trials of colchicine and anakinra are further assessing their roles in cytokine storm management. Additionally, cardiac MRI can aid in diagnosing myocarditis or inflammatory cardiomyopathy in suspected cases. Altogether, while outcomes remain poor in patients with both SARS-CoV-2 infection and underlying cardiovascular disease, integrating anti-inflammatory, antiviral, and standard cardiovascular therapies offers the most effective approach to patient management (Table 3).

Table 3: Potential Treatment Options and Future Perspectives for Cardiovascular Complications in COVID-19.

|

Category |

Therapeutic Options |

Mechanism / Role |

Clinical Considerations |

References |

|

A. Anti-inflammatory and Immunomodulatory Therapies |

Corticosteroids (e.g., dexamethasone) |

Reduce systemic inflammation and cytokine storm |

Improves survival in severe/critical COVID-19; risk of secondary infections |

|

|

IL-6 inhibitors (e.g., tocilizumab) |

Block IL-6 signaling to attenuate hyperinflammation |

Beneficial in severe cytokine storm; monitor for infection risk |

||

|

JAK inhibitors (e.g., baricitinib) |

Inhibit JAK-STAT pathway, reducing cytokine signaling |

May decrease progression to severe disease; careful monitoring needed |

||

|

Colchicine |

Anti-inflammatory effects via microtubule disruption |

Potential cardioprotective effects; data still emerging |

[90–92] |

|

|

B. Antithrombotic and Anticoagulant Therapies |

Heparin, LMWH |

Prevent thromboembolism and microthrombosis |

Recommended in hospitalized patients; adjust dose based on risk |

|

|

Antiplatelet agents |

Inhibit platelet aggregation |

May reduce thrombotic complications; evidence still evolving |

[93] |

|

|

C. Cardiovascular Supportive Therapies |

Standard heart failure management |

ACE inhibitors, ARBs, β-blockers, diuretics |

Continue or initiate as indicated; monitor hemodynamics |

|

|

Anti-arrhythmic agents |

Control atrial/ventricular arrhythmias |

Requires ECG monitoring; drug–drug interactions with antivirals possible |

||

|

Oxygen therapy, mechanical ventilation |

Improve oxygen delivery and reduce cardiac stress |

Critical in severe hypoxemia; invasive support as last resort |

[94,95] |

|

|

D. Emerging and Investigational Options |

Monoclonal antibodies |

Neutralize viruses or modulate immune response |

Promising but limited evidence in CV-specific outcomes |

|

|

Novel antiviral–anti-inflammatory combinations |

Target viral replication and inflammation simultaneously |

Under clinical trials; potential to reduce CV burden |

[96] |

Future Perspectives

Emerging evidence from 2024-2025 highlights that COVID-19 can cause persistent cardiovascular complications, including heart failure, arrhythmia, stroke, endothelial dysfunction, and microthrombosis, even in individuals with mild acute disease. Longitudinal monitoring and early cardiovascular screening are crucial for post-COVID patients, while precision medicine approaches using biomarkers and AI-based risk prediction can enable tailored interventions. Vaccination remains protective against long-term cardiovascular events, and the integration of digital health tools, such as telemedicine and wearable devices, can facilitate continuous monitoring and timely management. These insights underscore the need for ongoing research, preventive strategies, and innovative therapies to mitigate long-term cardiovascular risk in COVID-19 survivors [97].

Conclusion

COVID-19, caused by SARS-CoV-2, has affected more than 215 countries and is closely associated with cardiovascular complications. The virus invades ACE2 receptor–bearing cells, triggering endothelial dysfunction, systemic inflammation, pyroptosis, apoptosis, and impaired microcirculatory function. Patients with reduced ACE2 expression, diabetes, and atherosclerosis are particularly vulnerable to vascular injury. Cardiovascular diseases are more prevalent in COVID-19 patients, and discontinuation of renin angiotensin aldosterone system (RAAS) inhibitors may worsen outcomes. Timely continuation of angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs), angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs), and mineralocorticoid receptor antagonists (MRAs) are therefore recommended to reduce mortality. In addition, heart failure therapies, alongside careful cardiovascular monitoring, remain essential for improving prognosis in patients with pre-existing cardiac disorders.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contribution

Muhammad Waqas Nasir has conceptualized, design the project, investigated the data, resource collection, Citation, data curation and formal analysis draft manuscript writing and editing the manuscript. Yong Gao conceived, designed, and administered the project, supervised, drafted manuscript writing, managed the funding and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All the authors read the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Ullah H, Ullah A, Gul A, Mousavi T, Khan MW. Novel coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic outbreak: A comprehensive review of the current literature. Vacunas (English Edition) 2021;22:106–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vacune.2020.09.005.

- Shao H-H, Yin R-X. Pathogenic mechanisms of cardiovascular damage in COVID-19. Molecular Medicine 2024;30:92. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10020-024-00855-2.

- Beyerstedt S, Casaro EB, Rangel ÉB. COVID-19: angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) expression and tissue susceptibility to SARS-CoV-2 infection. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 2021;40:905–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10096-020-04138-6.

- Xu S, Wu W, Zhang S. Manifestations and Mechanism ofTschöpe C, Ammirati E, Bozkurt B, Caforio ALP, Cooper LT, Felix SB, et al. Myocarditis and inflammatory cardiomyopathy: current evidence and future directions. Nat Rev Cardiol 2021;18:169–93. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41569-020-00435-x.

- Qian Y, Lei T, Patel PS, Lee CH, Monaghan-Nichols P, Xin H-B, et al. Direct Activation of Endothelial Cells by SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein Is Blocked by Simvastatin. Journal of Virology 2021. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01396-21.

- Varga Z, Flammer AJ, Steiger P, Haberecker M, Andermatt R, Zinkernagel AS, et al. Endothelial cell infection and endotheliitis in COVID-19. Lancet 2020;395:1417–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30937-5.

- Kamel MH, Yin W, Zavaro C, Francis JM, Chitalia VC. Hyperthrombotic Milieu in COVID-19 Patients. Cells 2020;9:2392. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells9112392.

- Raj K, Majeed H, Chandna S, Chitkara A, Sheikh AB, Kumar A, et al. Increased risk of pulmonary embolism and deep vein thrombosis with COVID-19 pneumonia in comparison to influenza pneumonia: insights from the National Inpatient Sample database. J Thorac Dis 2024;16:6161–70. https://doi.org/10.21037/jtd-23-1674.

- Georgieva E, Ananiev J, Yovchev Y, Arabadzhiev G, Abrashev H, Abrasheva D, et al. COVID-19 Complications: Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Mitochondrial and Endothelial Dysfunction. Int J Mol Sci 2023;24:14876. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms241914876.

- Chang R, Mamun A, Dominic A, Le N-T. SARS-CoV-2 Mediated Endothelial Dysfunction: The Potential Role of Chronic Oxidative Stress. Front Physiol 2021;11:605908. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2020.605908.

- Paranga TG, Mitu I, Pavel-Tanasa M, Rosu MF, Miftode I-L, Constantinescu D, et al. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: Exploring IL-6 Signaling and Cytokine-Microbiome Interactions as Emerging Therapeutic Approaches. Int J Mol Sci 2024;25:11411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms252111411.

- Zanza C, Romenskaya T, Manetti AC, Franceschi F, La Russa R, Bertozzi G, et al. Cytokine Storm in COVID-19: Immunopathogenesis and Therapy. Medicina (Kaunas) 2022;58:144. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina58020144.

- Chen R, Lan Z, Ye J, Pang L, Liu Y, Wu W, et al. CytokiBoonyawat K, Chantrathammachart P, Numthavej P, Nanthatanti N, Phusanti S, Phuphuakrat A, et al. Incidence of thromboembolism in patients with COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Thromb J 2020;18:34. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12959-020-00248-5.

- Page EM, Ariëns RAS. Mechanisms of thrombosis and cardiovascular complications in COVID-19. Thromb Res 2021;200:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.thromres.2021.01.005.

- Oudit GY, Wang K, Viveiros A, Kellner MJ, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2—at the heart of the COVID-19 pandemic. Cell 2023;186:906–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2023.01.039.

- Perez-Bermejo JA, Kang S, Rockwood SJ, Simoneau CR, Joy DA, Silva AC, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection of human iPSC-derived cardiac cells reflects cytopathic features in hearts of patients with COVID-19. Sci Transl Med 2021:eabf7872. https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.abf7872.

- Veluswamy P, Wacker M, Stavridis D, Reichel T, Schmidt H, Scherner M, et al. The SARS-CoV-2/Receptor Axis in Heart and Blood Vessels: A Crisp Update on COVID-19 Disease with Cardiovascular Complications. Viruses 2021;13:1346. https://doi.org/10.3390/v13071346.

- Gonzalez-Gonzalez FJ, Ziccardi MR, McCauley MD. Virchow’s Triad and the Role of Thrombosis in COVID-Related Stroke. Front Physiol 2021;12:769254. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.769254.

- Spears JR. Reperfusion Microvascular Ischemia After Prolonged Coronary Occlusion: Implications And Treatment With Local Supersaturated Oxygen Delivery. Hypoxia (Auckl) 2019;7:65–79. https://doi.org/10.2147/HP.S217955.

- Silva MJA, Ribeiro LR, Gouveia MIM, Marcelino B dos R, dos Santos CS, Lima KVBMoris D, Spartalis M, Spartalis E, Karachaliou G-S, Karaolanis GI, Tsourouflis G, et al. The role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular diseases and the clinical significance of myocardial redox. Ann Transl Med 2017;5:326. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2017.06.27.

- Hussain M, Khurram Syed S, Fatima M, Shaukat S, Saadullah M, Alqahtani AM, et al. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome and COVID-19: A Literature Review. J Inflamm Res 2021;14:7225–42. https://doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S334043.

- Smith LM, Glauser JM. Managing Severe Hypoxic Respiratory Failure in COVID-19. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep 2022;10:31–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40138-022-00245-0.

- Rabaan AA, Smajlović S, Tombuloglu H, ćordić S, Hajdarević A, Kudić N, et al. SARS-CoV-2 infection and multi-orLartey NL, Valle-Reyes S, Vargas-Robles H, Jiménez-Camacho KE, Guerrero-Fonseca IM, Castellanos-Martínez R, et al. ADAM17/MMP inhibition prevents neutrophilia and lung injury in a mouse model of COVID-19. J Leukoc Biol 2022;111:1147–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/JLB.3COVA0421-195RR.

- Singh SJ, Baldwin MM, Daynes E, Evans RA, Greening NJ, Jenkins RG, et al. Respiratory sequelae of COVID-19: pulmonary and extrapulmonary origins, and approaches to clinical care and rehabilitation. Lancet Respir Med 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(23)00159-5.

- Kwan PKW, Cross GB, Naftalin CM, Ahidjo BA, Mok CK, Fanusi F, et al. A blood RNA transcriptome signature for COVID-19. BMC Med Genomics 2021;14:155. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12920-021-01006-w.

- Samidurai A, Das A. Cardiovascular Complications Associated with COVID-19 and Potential Therapeutic Strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2020;21:6790. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21186790.

- Buonacera A, Stancanelli B, Colaci M, Malatino L. Neutrophil to Lymphocyte Ratio: An Emerging Marker of the Relationships between the Immune System and Diseases. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23:3636. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms23073636.

- Taqueti VR, Ridker PM. Inflammation, Coronary Flow Reserve, and Microvascular Dysfunction. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging 2013;6:668–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2013.02.005.

- Helms J, Combes A, Aissaoui N. Cardiac injury in COVID-19. Intensive Care Med 2022;48:111–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-021-06555-3.

- Palazzuoli A, Metra M, Collins SP, Adamo M, Ambrosy AP, Antohi LE, et al. Heart failure during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical, diagnostic, management, and organizational dilemmas. ESC Heart Fail 2022;9:3713–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/ehf2.14118.

- Wang Y, Wang Z, Tse G, Zhang L, Wan EY, Guo Y, et al. Cardiac arrhythmias in patients with COVID-19. J Arrhythm 2020;36:827–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/joa3.12405.

- Jayarangaiah A, Kariyanna PT, Chen X, Jayarangaiah A, Kumar A. COVID-19-Associated Coagulopathy: An Exacerbated Immunothrombosis Response. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2020;26:1076029620943293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1076029620943293.

- Sagar S, Liu PP, Cooper LT. Lancet 2012;379:738–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60648-X.

- Khalid Ahmed S, Gamal Mohamed M, Abdulrahman Essa R, Abdelaziz Ahmed Rashad Dabou E, Omar Abdulqadir S, Muhammad Omar R. Global reports of takotsubo (stress) cardiomyopathy following COVID-19 vaccination: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc 2022;43:101108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijcha.2022.101108.

- Terzic CM, Medina-Inojosa BJ. CARDIOVASCULAR COMPLICATIONS OF COVID-19. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmr.2023.03.003.

- Umei TC, Murata Y, Momiyama Y. Sudden cardiac death due to ventricular fibrillation in a case of giant cell myocarditis. J Cardiol Cases 2020;21:224–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jccase.2020.02.005.

- Dhakal BP, Sweitzer NK, Indik JH, Acharya D, William P. SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Cardiovascular Disease: COVID-19 Heart. Heart Lung Circ 2020;29:973–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hlc.2020.05.101.

- Abdelhafiz AH, Emmerton D, Sinclair AJ. Diabetes in COVID-19 pandemic-prevalence, patient characteristics and adverse outcomes. Int J Clin Pract 2021;75:e14112. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijcp.14112.

- Li B, Yang J, Zhao F, Zhi L, Wang X, Liu L, et al. Prevalence and impact of cardiovascular metabolic diseases on COVID-19 in China. Clin Res Cardiol 2020;109:531–8. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-020-01626-9.

- Brumback BD, Dmytrenko O, Robinson AN, Bailey AL, Ma P, Liu J, et al. Human Cardiac Pericytes Are Susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 Infection. JACC Basic Transl Sci 2022;8:109–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacbts.2022.09.001.

- Yordanova MG. High-Sensitive Cardiac Troponin I - An Important Biomarker in the Course of COVID-19 Disease in Adult Patients. OJCRR 2021;6:1–5.

- Solaro RJ, Rosas PC, Langa P, Warren CM, Wolska BM, Goldspink PH. Mechanisms of troponin release into serum in cardiac injury associated with COVID-19 patients. Int J Cardiol Cardiovasc Dis 2021;Volume 1:41–7. https://doi.org/10.46439/cardiology.1.006.

- de Candia P, Prattichizzo F, Garavelli S, Matarese G. T Cells: Warriors of SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Trends Immunol 2021;42:18–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2020.11.002.

- Synnott D, O’Reilly D, De Freitas D, Naidoo J. Cytokine release syndrome in solid tumors. Cancer 2025;131:e70069. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.70069.

- Cosenza M, Sacchi S, Pozzi S. Cytokine Release Syndrome Associated with T-Cell-Based Therapies for Hematological Malignancies: Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment. Int J Mol Sci 2021;22:7652. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms22147652.

- Kreutz M, Hennemann B, Ackermann U, Grage-Griebenow E, Krause SW, Andreesen R. Granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor modulates lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-binding and LPS-response of human macrophages: inverse regulation of tumour necrosis factor-alpha and interleukin-10. Immunology 1999;98:491–6. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2567.1999.00904.x.

- Umbrajkar S, Stankowski RV, Rezkalla S, Kloner RA. Cardiovascular Health and Disease in the Context of COVID-19. Cardiology Research 2021;12:67. https://doi.org/10.14740/cr.v12i2.1199.

- Jones EAV. Mechanism of COVID-19-Induced Cardiac Damage from Patient, In Vitro and Animal Studies. Curr Heart Fail Rep 2023;20:451–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11897-023-00618-w.

- Almutairi AS, Abunurah H, Hadi Alanazi A, Alenezi FK, Nagy H, Saad Almutairi N, et al. The immunological response among COVID-19 patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome. J Infect Public Health 2021;14:954–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jiph.2021.05.007.

- Carlini V, Noonan DM, Abdalalem E, Goletti D, Sansone C, Calabrone L, et al. The multifaceted nature of IL-10: regulation, role in immunological homeostasis and its relevance to cancer, COVID-19 and post-COVID conditions. Front Immunol 2023;14:1161067. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2023.1161067.

- Rabaan AA, Al-Ahmed SH, Muhammad J, Khan A, Sule AA, Tirupathi R, et al. Role of Inflammatory Cytokines in COVID-19 Patients: A Review on Molecular Mechanisms, Immune Functions, Immunopathology and Immunomodulatory Drugs to Counter Cytokine Storm. Vaccines 2021;9:436. https://doi.org/10.3390/vaccines9050436.

- Akhmerov A, Marbán E. COVID-19 and the Heart. Circulation Research 2020. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.317055.

- Shirakabe A, Matsushita M, Shibata Y, Shighihara S, Nishigoori S, Sawatani T, et al. Organ dysfunction, injury, and failure in cardiogenic shock. J Intensive Care 2023;11:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40560-023-00676-1.

- Giordo R, Paliogiannis P, Mangoni AA, Pintus G. SARS-CoV-2 and endothelial cell interaction in COVID-19: molecular perspectives. Vasc Biol 2021;3:R15–23. https://doi.org/10.1530/VB-20-0017.

- Pons S, Fodil S, Azoulay E, Zafrani L. The vascular endothelium: the cornerstone of organ dysfunction in severe SARS-CoV-2 infection. Critical Care 2020;24:353. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03062-7.

- Das A, Pathak S, Premkumar M, Sarpparajan CV, Balaji ER, Duttaroy AK, et al. A brief overview of SARS-CoV-2 infection and its management strategies: a recent update. Mol Cell Biochem 2024;479:2195–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11010-023-04848-3.

- Karki R, Kanneganti T-D. The ‘Cytokine Storm’: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Trends Immunol 2021;42:681–705. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.it.2021.06.001.

- Du P, Geng J, Wang F, Chen X, Huang Z, Wang Y. Role of IL-6 inhibitor in treatment of COVID-19-related cytokine release syndrome. Int J Med Sci 2021;18:1356–62. https://doi.org/10.7150/ijms.53564.

- Angriman F, Ferreyro BL, Burry L, Fan E, Ferguson ND, Husain S, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor blockade in patients with COVID-19: placing clinical trials into context. Lancet Respir Med 2021;9:655–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2213-2600(21)00139-9.

- Shetty A, Hanson R, Korsten P, Shawagfeh M, Arami S, Volkov S, et al. Tocilizumab in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and beyond. Drug Des Devel Ther 2014;8:349–64. https://doi.org/10.2147/DDDT.S41437.

- Elfiky AA. Ribavirin, Remdesivir, Sofosbuvir, Galidesivir, and Tenofovir against SARS-CoV-2 RNA dependent RNA polymerase (RdRp): A molecular docking study. Life Sci 2020;253:117592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lfs.2020.117592.

- Astiawati T, Rohman MS, Wihastuti T, Sujuti H, Endharti A, Sargowo D, et al. The Emerging Role of Colchicine to Inhibit NOD-like Receptor Family, Pyrin Domain Containing 3 Inflammasome and Interleukin-1β Expression in In Vitro Models. Biomolecules 2025;15:367. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15030367.

- Okada J, Yoshinaga T, Washio T, Sawada K, Sugiura S, Hisada T. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine provoke arrhythmias at concentrations higher than those clinically used to treat COVID-19: A simulation study. Clin Transl Sci 2021;14:1092–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/cts.12976.

- Agarwal S, Agarwal SK. Lopinavir-Ritonavir in SARS-CoV-2 Infection and Drug-Drug Interactions with Cardioactive Medications. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther 2021;35:427–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10557-020-07070-1.

- Jorgensen SCJ, Tse CLY, Burry L, Dresser LD. Baricitinib: A Review of Pharmacology, Safety, and Emerging Clinical Experience in COVID-19. Pharmacotherapy 2020;40:843–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/phar.2438.

- Zhao H, Zhang C, Zhu Q, Chen X, Chen G, Sun W, et al. Favipiravir in the treatment of patients with SARS-CoV-2 RNA recurrent positive after discharge: A multicenter, open-label, randomized trial. Int Immunopharmacol 2021;97:107702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intimp.2021.107702.

- Goker Bagca B, Biray Avci C. The potential of JAK/STAT pathway inhibition by ruxolitinib in the treatment of COVID-19. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2020;54:51–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cytogfr.2020.06.013.

- Bing SJ, Lyu C, Xu B, Wandu WS, Hinshaw SJ, Furumoto Y, et al. Tofacitinib inhibits the development of experimental autoimmune uveitis and reduces the proportions of Th1 but not of Th17 cells. Mol Vis 2020;26:641–51.

- Tran DT, Batchu SN, Advani A. Interferons and interferon-related pathways in heart disease. Front Cardiovasc Med 2024;11:1357343. https://doi.org/10.3389/fcvm.2024.1357343.

- Chao J, Viets Z, Donham P, Wood JG, Gonzalez NC. Dexamethasone blocks the systemic inflammation of alveolar hypoxia at several sites in the inflammatory cascade. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2012;303:H168–77. https://doi.org/10.1152/ajpheart.00106.2012.

- Reina J, Iglesias C. [Nirmatrelvir plus ritonavir (Paxlovid) a potent SARS-CoV-2 3CLpro protease inhibitor combination]. Rev Esp Quimioter 2022;35:236–40. https://doi.org/10.37201/req/002.2022.

- Kanagala SG, Dholiya H, Jhajj P, Patel MA, Gupta V, Gupta S, et al. Remdesivir-Induced Bradycardia. South Med J 2023;116:317–20. https://doi.org/10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001519.

- Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Noncritically Ill Patients with Covid-19. N Engl J Med 2021:NEJMoa2105911. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa2105911.

- Cavalli G, Dinarello CA. Anakinra Therapy for Non-cancer Inflammatory Diseases. Front Pharmacol 2018;9:1157. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2018.01157.

- June RR, Olsen NJ. Drug Evaluation. Expert Opin Biol Ther 2016;16:1303–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/14712598.2016.1217988.

- Taylor PC, Bieber T, Alten R, Witte T, Galloway J, Deberdt W, et al. Baricitinib Safety for Events of Special Interest in Populations at Risk: Analysis from Randomised Trial Data Across Rheumatologic and Dermatologic Indications. Adv Ther 2023;40:1867–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-023-02445-w.

- Saleh M, Gabriels J, Chang D, Soo Kim B, Mansoor A, Mahmood E, et al. Effect of Chloroquine, Hydroxychloroquine, and Azithromycin on the Corrected QT Interval in Patients With SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2020;13:e008662. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCEP.120.008662.

- Kabinger F, Stiller C, Schmitzová J, Dienemann C, Kokic G, Hillen HS, et al. Mechanism of molnupiravir-induced SARS-CoV-2 mutagenesis. Nat Struct Mol Biol 2021;28:740–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41594-021-00651-0.

- Abraham S, Nohria A, Neilan TG, Asnani A, Saji AM, Shah J, et al. Cardiovascular Drug Interactions With Nirmatrelvir/Ritonavir in Patients With COVID-19. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022;80:1912–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2022.08.800.

- Rathi C, Pipaliya N, Choksi D, Parikh P, Ingle M, Sawant P. Autoimmune Hepatitis Triggered by Treatment With Pegylated Interferon α-2a and Ribavirin for Chronic Hepatitis C. ACG Case Rep J 2015;2:247–9. https://doi.org/10.14309/crj.2015.74.

- Nasir MW, Gao Y. Advances in KSHV Research: Molecular Pathogenesis, Immune Evasion, and Evolving Therapeutic Horizon. J Med Virol 2025;97:e70695. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.70695.

- Gasparyan AY, Kitas GD. Hyperinflammation due to COVID-19 and the Targeted Use of Interleukin-1 Inhibitors. Mediterr J Rheumatol 2022;33:173–5. https://doi.org/10.31138/mjr.33.2.173.

- Amaral NB, Rodrigues TS, Giannini MC, Lopes MI, Bonjorno LP, Menezes PISO, et al. Colchicine reduces the activation of NLRP3 inflammasome in COVID-19 patients. Inflamm Res 2023;72:895–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00011-023-01718-y.

- Zhang W, Qin C, Fei Y, Shen M, Zhou Y, Zhang Y, et al. Anti-inflammatory and immune therapy in severe coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients: An update. Clin Immunol 2022;239:109022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2022.109022.

- Zizzo G, Tamburello A, Castelnovo L, Laria A, Mumoli N, Faggioli PM, et al. Immunotherapy of COVID-19: Inside and Beyond IL-6 Signalling. Front Immunol 2022;13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2022.795315.

- Mohammed MA. Fighting cytokine storm and immunomodulatory deficiency: By using natural products therapy up to now. Front Pharmacol 2023;14:1111329. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2023.1111329.

- Hirsh J, Anand SS, Halperin JL, Fuster V. Guide to Anticoagulant Therapy: Heparin. Circulation 2001. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.CIR.103.24.2994.

- King GS, Goyal A, Grigorova Y, Patel P, Hashmi MF. Antiarrhythmic Medications. StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025.

- van der Horst ICC, Voors AA, van Veldhuisen DJ. Treatment of heart failure with ACE inhibitors and beta-blockers. Clin Res Cardiol 2007;96:193–5. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00392-007-0487-y.

- Wang J, Ni S, Chen Q, Wang C, Liu H, Huang L, et al. Discovery of a Novel Public Antibody Lineage Correlated With Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine and the Resultant Neutralization Activity. Journal of Medical Virology 2024;96:e70073. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmv.70073.

- Zhang B, Thacker D, Zhou T, Zhang D, Lei Y, Chen J, et al. Cardiovascular post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 in children and adolescents: cohort study using electronic health records. Nat Commun 2025;16:3445. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-56284-0.

Impact Factor: * 3.5

Impact Factor: * 3.5 Acceptance Rate: 71.36%

Acceptance Rate: 71.36%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks