Plant-based Expression of SARS-CoV-2 antigens for use in an Oral Vaccine

Monique Power1, Taha Azad2,3, John C Bell2,3, Allyson M MacLean1*

1Department of Biology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa ON, K1N 6N5, Canada

*Corresponding Author: Allyson M MacLean, Department of Biology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa ON, K1N 6N5, Canada

Received: 03 December 2021; Accepted: 09 December 2021; Published: 11 July 2022

Article Information

Citation: Monique Power, Taha Azad, John C Bell, and Allyson M MacLean. Plant-based Expression of SARS-CoV-2 antigens for use in an Oral Vaccine. Journal of Food Science and Nutrition Research 5 (2022): 591-593.

DOI: 10.26502/jfsnr.2642-110000101

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

While almost 300 vaccines against COVID-19 are presently in development, only a small minority (3%) explore the potential of oral vaccines (WHO). Oral vaccines produced in plants offer several advantages over traditional processes, including lower research and production costs, ease of scalability, and a negligible risk of contamination with human pathogens

Keywords

<p>SARS-CoV-2 antigens, Vaccines, Antigens</p>

Article Details

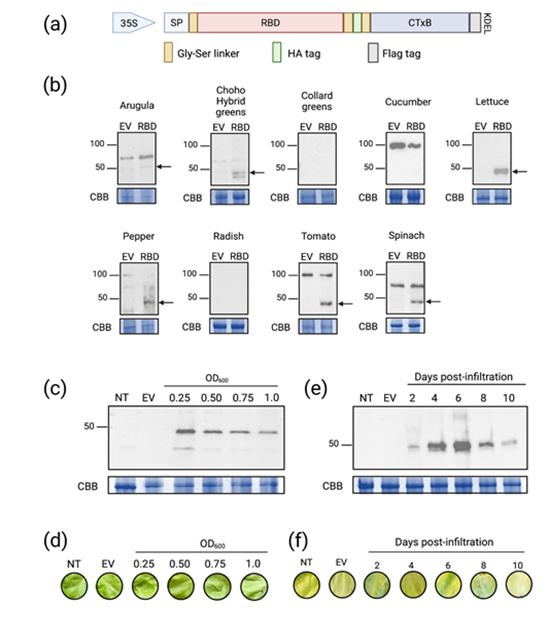

While almost 300 vaccines against COVID-19 are presently in development, only a small minority (3%) explore the potential of oral vaccines (WHO). Oral vaccines produced in plants offer several advantages over traditional processes, including lower research and production costs, ease of scalability, and a negligible risk of contamination with human pathogens [1]. Reduced costs and increased ease of transportation and storage are particularly critical parameters towards facilitating equitable vaccine access to the world’s population [1]. Plant-based oral vaccines entail the expression of antigenic material within plants that, upon ingestion, elicits an immune response that is subsequently protective against disease [1]. A wide variety of plants have been explored to develop oral vaccines against an equally broad range of diseases. In an example that is highly relevant to this research, a subunit of the Spike protein of SARS-CoV was shown to induce SARS-CoV-specific IgA in mice after oral ingestion of transgenic tomato [2]. The mechanisms by which plant-based oral vaccines elicit an immune response have been studied in detail [1]. Ingested foods do not typically elicit an immune response, thus, to ensure efficient uptake by microfold cells within gut-associated lymphoid tissue, antigens may be fused to mucosal carrier proteins (e.g., B subunit of cholera toxin; CTxB). Plant-based oral vaccines have been shown to induce both cellular and humoral immunity within the mucosal and systemic immune systems [1,3]. Because the initial site of SARS-CoV-2 infection is within the respiratory mucosa, efforts to develop mucosal vaccines (oral or intra-nasal) are an important complement to conventional vaccines [4]. This study aimed to optimize methods for the in planta expression of recombinant protein corresponding to the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) subunit of the surface-exposed Spike (S) glycoprotein of SARS-CoV-2. The RBD is a primary target of vaccine strategies against COVID-19, and most neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 correspond to RBD [5,6]. We evaluated the suitability of nine edible plant species to express the viral antigen following transient transformation mediated by Agrobacterium tumefaciens, and then established parameters for optimal RBD expression in the most promising host plant. Expression of recombinant proteins was trialed in lettuce (Lactuca sativa L. cv. Hilde II Improved), spinach (Spinacia oleracea L. cv. C2-608 Speedy Hybrid), collard greens (Brassica oleracea L. var. viridis), cucumber (Cucumis sativus L. cv Spartan Dawn F1 Hybrid), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum L. cv. Matina Organic), radish (Raphanus sativus L. cv. Cherry Belle), arugula (Eruca vesicaria L. (Cav.) ssp. sativa cv. Salad Rocket), peppers (Capsicum annuum L. cv. Purple Star Hybrid), and Choho Hybrid greens (Brassica rapa L. subsp. narinosa x Brassica rapa L. var. perviridis). The plasmid vector selected for the expression of SARS-CoV-2 RBD in planta is pHREAC, which has been demonstrated to support a high level of protein expression in Nicotiana benthamiana [7]. The viral gene construct consists primarily of codon optimized (for expression in N. benthamiana) sequence corresponding to the RBD of the Spike glycoprotein (aa 329 to aa 522), fused to a cholera toxin B subunit (CTxB) to promote recombinant protein uptake across the intestinal epithelium. The expressed recombinant protein, RBD-CTxB, has a molecular mass of 40.3 kDa and includes HA- and FLAG-tags for antibody recognition (Figure 1a). Amongst the edible plants, the highest and most consistent expression of RBD-CTxB was found in lettuce (Figure 1b). Faint and/or inconsistent recombinant viral protein expression was observed in arugula, Choho Hybrid greens, pepper, spinach, and tomato. Arugula, Choho Hybrid greens and spinach showed no visible chlorosis or necrosis after infiltration, although tomato and pepper leaves developed both chlorosis and necrosis after infiltration. No expression of viral protein was observed in collard greens or radish, and leaves from these plants did not show visible damage from agroinfiltration. Lettuce was selected as the preferred host for edible vaccine production, as it consistently produced the highest expression of RBD-CTxB (based upon immunoblot analyses) and did not exhibit evidence of necrosis after agroinfiltration. We next assessed the optimal parameters to maximize protein expression in this host. We observed comparable expression of RBD-CTxB between leaves infiltrated with an Agrobacterium suspension adjusted to an OD600 of 0.25 and 0.50, with minimal to no visible signs of chlorosis or necrosis (Figure 1c). Some yellowing was observed in tissue infiltrated at OD600 of 0.75 and 1.0, thus we decided to select an OD600 of 0.5 in subsequent experiments to minimize stress to the plant host (Figure 1d). We also monitored accumulation of RBD-CTxB at 2 to 10 days post-infiltration (dpi) to determine the timepoint at which expression is highest (Figure 1e) and damage to tissues was minimal (Figure 1f). RBD-CTxB expression appears to increase with time to achieve highest levels at 6 dpi, then declines from 8 dpi to 10 dpi. To obtain the highest possible expression of the protein of interest, our data indicate that lettuce plants should be harvested 6 days after infiltration. In summary, this study represents the first published protocol to express SARS-CoV-2 viral antigen in an edible plant species, a key step towards achieving the goal of developing a plant-based oral vaccine that is protective against COVID-19. Plant-based edible vaccines offer excellent potential towards enhancing equity in vaccine development and distribution in low-income developing countries, many of which report fewer than 2% of citizens as receiving even a single COVID-19 vaccine dose [8].

Figure 1: Optimization of expression of the Receptor Binding Domain (RBD) of SARS-CoV-2 Spike glycoprotein in an edible plant.

(a) Schematic depiction of construct used to express RBD in planta. 35S, 35S CaMV promoter. SP, signal peptide PR-1a Nicotiana tabacum (aa 1-30). RBD corresponds to (aa 329 to aa 522) of the Wuhan-Hu-1 isolate of SARS-CoV-2. CTxB, B subunit of cholera toxin. KDEL, ER retention signal.

(b) Anti-FLAG immunoblots to assess relative expression of RBD-CTxB recombinant protein in nine edible plant species. Arrows identify bands that correspond to the predicted molecular mass of RBD-CTxB (40.3 kDa).

(c) Anti-FLAG immunoblot to assess RBD-CTxB expression following infiltration of lettuce with A. tumefaciens (RBD-CTxB/pHREAC), with adjusted OD600 as specified in panel. (d) Representative pictures of lettuce infiltrated with A. tumefaciens adjusted to OD600 as specified in panel. Leaf tissue was photographed 6 days post-infiltration of EV and RBD-CTxB.

(e) Anti-FLAG immunoblot to assess RBD-CTxB expression over time, in lettuce infiltrated with an adjusted OD600 of 0.50.

(f) Representative pictures of lettuce infiltrated with A. tumefaciens adjusted to an OD600 of 0.50. Leaf tissue was photographed 2 to 10 days post-infiltration of EV and RBD-CTxB, as indicated in panel. For panels (b to f), lettuce refers to Lactuca sativa L. cv. Hilde II Improved. NT, non-transformed lettuce, collected (b) 4 days or (c to f) 6 days after infiltration of RBD-CTxB samples. EV, infiltration of A. tumefaciens (pHREAC), adjusted to OD600 of 0.50, collected (b) 4 days or (c to f) 6 days dpi. CBB, Coomassie Brilliant Blue stained SDS-PAGE to assess protein loading.

Author Contributions

AMM and TA conceived and designed the project. MP performed all agroinfiltration experiments and immunoblots. MP and AMM contributed to the writing of the manuscript, with edits from TA and JCB. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for helpful discussions and advice from Rima Menassa and colleagues at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Emmanuel Margolin, Edward Rybicki and colleagues from Biopharming Research Unit, University of Cape Town. We gratefully acknowledge the excellent support of Michelle Brazeau, University of Ottawa, in her management of our greenhouse. This study was supported in part by funding from the University of Ottawa Faculty of Science.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Chan HT, Daniell H. Plant-made oral vaccines against human infectious diseases- Are we there yet? Plant Biotechnology Journal 12 (2015): 91-98.

- Pogrebnyak N, Golovkin M, Andrianov V, et al. Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) S- protein production in plants: Development of recombinant vaccine. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (2005).

- Sack M, Hofbauer A, Fischer R, et al. The increasing value of plant-made proteins. Current Opinion in Biotechnology (2015).

- Rosales-Mendoza S, Márquez-Escobar VA, González-Ortega O, et al. What does plant-based vaccine technology offer to the fight against COVID-19? Vaccines 12 (2020): 89-95.

- Garcia-Beltran WF, Lam EC, Astudillo MG, et al. COVID-19-neutralizing antibodies predict disease severity and survival. Cell 12 (2021): 184.

- Yang J, Wang W, Chen Z, et al. A vaccine targeting the RBD of the S protein of SARS-CoV-2 induces protective immunity. Nature 14 (2020): 586-595.

- Peyret H, Brown JKM, Lomonossoff Improving plant transient expression through the rational design of synthetic 5′ and 3′ untranslated regions. Plant Methods 11 (2019): 16-20.

- Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E, Beltekian D, et al. (2021) Coronavirus Pandemic (COVID-19). Our World in Data (2019).

Impact Factor: * 3.8

Impact Factor: * 3.8 Acceptance Rate: 77.96%

Acceptance Rate: 77.96%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks