SARS-CoV-2: A Virological, Pathological, and Evolutionary Guide

Muhammad Waqas Nasir1, Wangjing1, Xiangyu Zhang1, Mahir Azmal2, Ajit Ghosh2, Yong Gao*,1

1The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, 230001, China

2Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Shahjalal University of Science and Technology, Sylhet 3114, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author: Yong Gao, The First Affiliated Hospital of USTC, Division of Life Sciences and Medicine, University of Science and Technology of China, Hefei, Anhui, 230001, China.

Received: 05 December 2025; Accepted: 08 December 2025; Published: 16 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Muhammad Waqas Nasir, Wangjing, Xiangyu Zhang, Mahir Azmal, Ajit Ghosh, Yong Gao. SARS-CoV-2: A Virological, Pathological, and Evolutionary Guide. Archives of Microbiology and Immunologyy. 9 (2025): 276-290.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The COVID-19 pandemic, driven by SARS-CoV-2, has profoundly affected global public health and catalyzed an unprecedented surge in scientific discovery. This comprehensive review examines SARS-CoV-2 from evolutionary, virological, and pathological perspectives, providing an in-depth analysis of the structural and functional roles of key viral proteins, including spike (S), envelope (E), nucleocapsid (N), and membrane (M) in viral replication, immune system evasion, and host cell interactions. Mechanisms of viral entry are explored, highlighting the interplay between the viral spike protein and host cellular receptors such as ACE2, TMPRSS2, CD147, and Neuropilin-1, as well as their associated entry pathways. The review further discusses the genomic architecture of SARS-CoV-2, its tropism for specific tissues, and its remarkable capacity for adaptation and pathogenicity. The emergence and global dissemination of SARS-CoV-2 variants including both variants of concern and variants of interest are analyzed with respect to genetic mutations, transmission dynamics, and public health implications. Diagnostic advancements are addressed, with particular focus on gold-standard RT-PCR testing, CRISPR-based detection methods, and their roles in effective disease surveillance. Therapeutic strategies targeting both viral and host factors are evaluated, alongside immunological phenomena such as immune evasion, cytokine storm syndromes, and the regulatory influence of non-coding RNAs. In conclusion, this review reflects on the future trajectory of SARS-CoV-2, highlighting ongoing immune challenges, the likely transition to endemicity, and the necessity for sustained global preparedness.

Keywords

<p>SARS-CoV-2, Spike protein, Viral replication, COVID-19 diagnostics, Immunity evasion, Vaccines, Host-pathogen interaction, Variants of concerns</p>

Article Details

Introduction

Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), the causative agent of COVID-19, has dramatically reshaped global public health, economic stability, and social interactions since its emergence in late 2019. This unprecedented global health crisis has accelerated a robust scientific response, significantly advancing our understanding of coronavirus biology, disease pathogenesis, and virus-host interactions. The SARS-CoV-2 virion is characterized by a set of structural proteins spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) each integral to the virus's replication cycle, pathogenicity, and immune evasion strategies(1). Among these, the spike protein has garnered substantial attention for its pivotal role in mediating viral entry via interaction with host receptors such as Angiotensin-Converting Enzyme 2 (ACE2), Transmembrane Serine Protease 2 (TMPRSS2), Neuropilin-1 (NRP1), and Cluster of Differentiation 147 (CD147). Understanding these molecular interactions is critical for developing targeted antiviral strategies and vaccines. In addition to structural studies, genomic investigations have uncovered considerable genetic diversity within SARS-CoV-2, leading to the emergence of multiple variants of concern (VOCs) and variants of interest (VOIs), such as Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron, which demonstrate varying degrees of transmissibility, immune escape, and clinical outcomes(2–5). This genetic plasticity highlights the necessity of sustained genomic surveillance to guide public health interventions. Diagnostic and therapeutic approaches have rapidly evolved in response to the pandemic, with methods such as RT-PCR, antigen testing, CRISPR-based diagnostics, and advanced imaging techniques providing essential tools for virus detection and patient management. Concurrently, vaccine development, employing diverse platforms such as mRNA vaccines, viral vectors, protein subunits, and inactivated viruses, has significantly mitigated disease severity and spread. However, SARS-CoV-2 continues to pose substantial challenges through its sophisticated immune evasion mechanisms, including cytokine storms, impairment of adaptive immunity, and exploitation of host cell pathways. Additionally, the roles of non-coding RNAs and exosomes in modulating host-virus interactions and disease pathology present new avenues for research and therapeutic intervention (6,7).

Structural and Molecular Virology of SARS-CoV-2

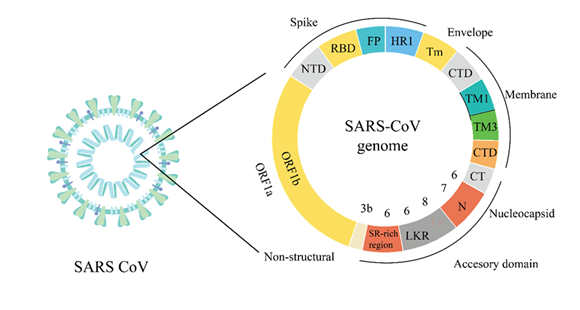

SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of COVID-19, is an enveloped, positive-sense single-stranded RNA virus belonging to the Coronaviridae family. Its virion architecture comprises four primary structural proteins spike (S), envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) each playing critical roles in viral replication, assembly, infection, and host immune evasion (Figure 1).

The schematic illustrates the virion structure and genomic layout of SARS-CoV-2, highlighting its primary structural proteins: Spike (S), Envelope (E), Membrane (M), and Nucleocapsid (N). The viral genome encodes essential domains including the receptor-binding domain (RBD), fusion peptide (FP), heptad repeat (HR1), and transmembrane domains (TM). The non-structural proteins are encoded by open reading frames (ORF1a and ORF1b). The spike protein is particularly significant for facilitating viral entry into host cells by binding to cell surface receptors, such as angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2). Meanwhile, the envelope protein contributes to virus assembly and budding, influencing virion integrity and infectivity. The membrane protein, being the most abundant structural protein, is central to maintaining the virion shape and assisting in protein interactions essential for assembly. The nucleocapsid protein encapsulates and protects the RNA genome, facilitating viral replication and transcription. Understanding these structural and molecular characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 is critical for identifying effective therapeutic targets and developing vaccines and antiviral strategies to manage the ongoing pandemic.

Structural Proteins of SARS-CoV-2

COVID-19 is primarily caused by the SARS-CoV-2 virion, a structure consisting of four structural proteins (spike, membrane, envelope, nucleocapsid) and the RNA genome. The virus uses its S protein as a principal element to alter cells successfully by binding to ACE2 receptors on host cell surfaces. Through its extension from the viral envelope, the protein attaches to ACE2 receptors on cell surfaces to start an infection process (8). The spike protein of SARS-CoV-2, with its multiple domains in the amino acid chain of protein and the C-terminal domain (residues 438-607), is particularly significant for its interaction with host receptors, as depicted in Figure 1. The receptor binding domain (RBD), a 223-amino-acid residue segment occupying positions 319-541, is a critical region directly interacting with the ACE2 receptor (9). The receptor binding domain (RBD) is the portion of the spike protein that tends to bind with the ACE2 receptor, helping the virus enter the host cell. The entry of the virus into the host cells critically depends on the RBD and heptad repeat regions. The heptad repeats regions define the portions that help in the fusion of the membrane through coil interactions. Heptad repeat regions include the first heptad region (HR1; residues 912-984) and the second heptad region (HR2; residues 1163-1213) that are required for changes in the spike protein to form the fusion competent conformation (10). Integrin alpha 2 is also involved in the transmembrane domain (TM, 1213-1237 amino acids), which fixes the spike protein on the viral envelope, whereas the cytoplasmic tail domain (CT, 1237-1273 amino acids) is located within the virion (11).

The SARS-CoV-2 virus exploits the envelope (E) protein as a small transmembrane protein to accomplish assembly as well as budding and cause disease progression. The E protein's diverse functions support viral structural integrity and membrane interactions during infection. This highlights the need for ongoing research to understand virus mechanisms and life cycle dynamics. The proposed structural-functional model of the viral envelope protein is illustrated as a detailed outline of three domains. The N-terminal domain (NTD), also known as N-terminus, covers amino acids 1 to 8 and is shown on the left side of Figure 1. As the name suggests, the NTD is located at the amino or N terminus of the polypeptide chain. Occasionally, these contacts connect relevant proteins, as shown in Figure 1, strengthening viral adherence and subsequent access to target cells at the onset of viral infections. The membrane (M) protein, a major structural component of SARS-CoV-2, is crucial for maintaining the virus's shape and stability. The M protein is incorporated with high density within the lipid viral envelope and is involved in virion assembly and release. It also facilitates protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions critical to viral assembly. A detailed understanding of the membrane (M) protein structure offers added functionality towards realizing its role in SARS-CoV-2 particle formation and stabilization (12).

Profound elucidation of the membrane (M) protein structure offers added functionality towards realizing the SARS-CoV-2 virus structure (13). On the side of the interior of the membrane is the C-terminal beta-sheet that binds with the N protein used in organizing virion assembly (14). The structure also contains a small, positively charged N-arm region (residues 1-43) of unknown function (15). M protein of the virus is an essential structural protein that contributes to the overall stability of the SARS-CoV-2 particle structure through participation in protein-protein and protein-membrane interactions (16). SARS-CoV-2 uses its 29,800-nucleotide base single-stranded RNA genome to determine its fundamental properties like structure, replication and its function. Its genetically compact genome holds several open reading frames (ORFs) that generate vital virus proteins crucial for replication while facilitating particle assembly and cellular interaction. ORF1a and ORF1b comprise the longest part of the genome; both are responsible for encoding 16 nsp proteins essential mainly for transcription and replication (17).

Receptors

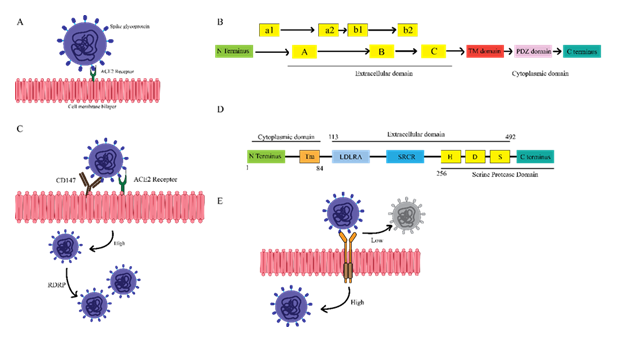

The domain architecture and functional diversity of the primary SARS-CoV-2 host receptors ACE2, NRP1, and CD147 provide distinct structural features that enable multiple viral entry pathways and create opportunities for competitive inhibition and neutralization. ACE2 acts as the principal entry receptor for SARS-CoV-2, mediating direct viral attachment and membrane fusion, while NRP1 and CD147 offer alternative or complementary routes for viral internalization. The key structural domains of each receptor not only facilitate viral entry but also participate in immune modulation. The interplay between soluble and membrane-bound ACE2 demonstrates a potential mechanism for competitive viral neutralization, whereas NRP1 and CD147 expand the repertoire of entry mechanisms available to the virus. This structural complexity highlights the significance of targeting multiple receptors and domains in the development of effective therapeutic interventions.

(A) ACE2: Shows N terminus (green), peptidase domains A-C (yellow), TM domain (red), PDZ-binding (pink), and C terminus (teal). Key regions for spike binding and membrane signaling. (B) NRP1: Displays N terminus (green), a1/a2 and b1/b2 domains (yellow), C domain, TM region (red), PDZ domain (pink), and C terminus (teal), indicating extracellular viral binding sites and signaling motifs. (C) ACE2-mediated entry: Stepwise binding of SARS-CoV-2 spike to ACE2, leading to membrane fusion and viral entry. (D) CD147: Shows N terminus (green), LDLRA and SRCR domains (blue), H/D/S motifs (yellow), TM domain (orange), and C terminus (teal). Involved in receptor-mediated endocytosis as an alternative viral entry route. (E) NRP1-mediated entry: Illustrates SARS-CoV-2 binding to NRP1, facilitating viral internalization, especially in low-ACE2 tissues, and enhancing infection alongside ACE2.

The first pathway illustrates the interaction between SARS-CoV-2 spike proteins and ACE2 receptors on the host cell membrane, as shown in Figure 2A. Connecting to the spike receptor triggers changes in the virus envelope, which permits fusion with the host's membrane and spreads the virus' genetic material inside the host cell (18). The second pathway suggests a defense mechanism in soluble ACE2 receptors. Also, the soluble receptors bind to the spike proteins of close SARS-CoV-2 viruses, preventing contact with membrane-bound ACE2. Soluble ACE2 may impede viral attachment and entry to host cells because it binds directly to the receptor-binding domain in the spike protein (19). The structural outline in Figure 2B illustrates the Accessory Domain and the Structural Domain of Neuropilin-1 (NRP1), a cell surface transmembrane receptor protein in several physiological processes such as signaling and immune responses. The Accessory Domain helps in the interactions of the external ligands like SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, whereas the Structural Domain helps in maintaining the structure of the receptor and its function. A study of NRP1 structure reveals the extracellular domain, the transmembrane domain, and the cytoplasmic domain. These A, B, and C subdomains help interact with ligands such as VEGF and class 3 semaphorins (SEMA3s) (20). Namely, the b1 subdomain may bind with the spike glycoprotein of the SARS-CoV-2 virus implicated in the disease. The only NRP1 structure projecting into the cellular interior is the single-pass transmembrane (TM) domain (it allows the cell membrane to anchor the protein in its place) represented here as a blue box within the horizontal black and white lipid bilayer that signifies the plasma membrane. This TM segment links extracellular communication and intracellular signaling networks. NRP1 has a red cytoplasmic domain at the C-terminus end labeled PDZ (Post-synaptic Density 95/Discs large/ZO-1) binding motif (that allows the protein to interact with the scaffolding proteins). This PDZ domain is used to mediate the binding of intracellular adapter proteins (21). In brief, the NRP1 transmembrane protein has three lobes, A, B, and C, on the outer side of the cell membrane, one TM domain across the membrane, and a PDZ domain in the cytoplasmic membrane. This enables NRP1 to signal outside in by binding to extracellular ligands through the A, B, and C regions and to intracellular proteins through its cytoplasmic PDZ domain and exercising various regulatory functions in different cell processes such as viral entry.

The spikes attach themselves to specific receptors on the host cell surface, mainly ACE2, depicted as oval yellow cups, and CD 147. ACE2 is suggested to permit direct viral fusion at the cell membrane as shown in Figure 2C. However, CD147 enables the endocytic route of virus entry (22). The attachment of spike proteins to these important portals facilitates the uncoating of the positive-sense single-stranded RNA gene, depicted by yellow structures within the viral particles within the host cell cytoplasm (23). TMPRSS2, also known as Transmembrane Serine Protease 2, is a pivotal enzyme involved in several crucial processes, including viral entry, cancer development, and substrate cleavage. Its role in viral entry, especially in activating viral spike proteins, particularly those from SARSCoV-2, by cleaving them to allow membrane fusion and ACE2 interaction, is of paramount importance (24).

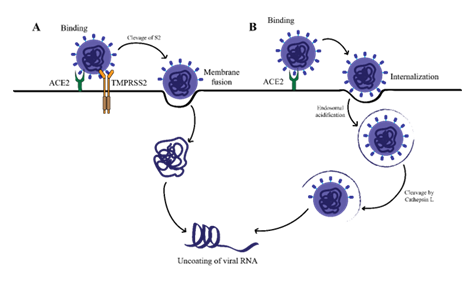

Cell/tissue tropism

SARS-CoV-2 operates via two different pathways for viral fusion and entry into cells. One involves endocytosis activated by cathepsin on endosomes, and a second at the cell surface supported by TMPRSS2 (25). These pathways originate from the interaction between ACE2 receptors and the viral S protein. Thus, strategies that gradually impair receptor binding ability inhibit the specific membrane fusion steps or decrease metabolic enzymes such as proteases essential to these pathways will help to prevent viral penetration. Mapping the molecule-level route of SARS-CoV-2 cellular entry provides insights into disease progression and informs rational approaches to drug targeting as illustrated in Figure 3.

The illustration depicts several key antiviral processes: neutralizing antibodies bind to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, preventing its interaction with the ACE2 receptor and subsequent viral entry into host cells. The figure also shows that for successful viral fusion and entry, the spike protein must be primed by the host cell surface protease TMPRSS2, which cleaves the spike protein following ACE2 engagement.

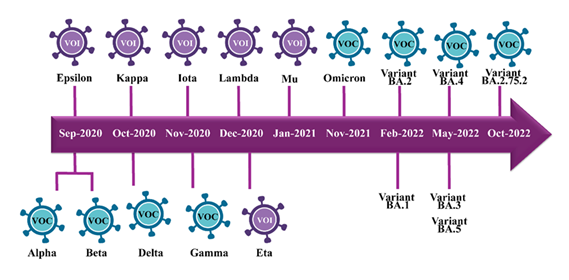

Epidemiology and History

While COVID-19 was ongoing, SARS-CoV-2 viruses showed mutation, and new strains emerged, some of which the WHO classified as variants of interest (VOI) or variants of concern (VOCs). Moreover, the approximate timescale of each variant's emergence also shows that one mutant strain rises after another throughout 2020 and 2021, and it often happens in one to several-month intervals (26). Prominently highlighted among the VOCs are five worrisome variants. These include Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and the latest one, Omicron. The alpha variant, also known as B.1.1.7 lineage, emerged in September 2020 and was seen to spread more quickly (27). At the same time, Beta (B.1.351) has also risen successfully to the challenge of evading prior immunity (28). A few months later, in November, the Gamma (P.1) variant emerged, characterized by reinfection and lesser vaccine efficacy (29). However, Delta (B.1.617.2 sublineage) is referred to as the most rampant VOC worldwide after emerging in October 2020 as more infectious (30). It possesses a more significant immune takeover in vaccinated persons than previous strains. The last and late Omicron (B.1.1.529 lineage) in November 2021 was the variant representing the most significant mutations of SARS-CoV-2, as shown in Figure 4. Its extensive alterations created a unique envelope structure, causing mass alerts about preventing infectious spread and decreasing severe illness (31).

Variants of interest (VOI; purple icons) including Epsilon, Kappa, Iota, Lambda, Mu, and Eta are shown above the timeline, while variants of concern (VOC; blue icons) Alpha, Beta, Delta, Gamma, Omicron, and multiple Omicron sub-lineages (BA.1, BA.2, BA.3, BA.4, BA.5, and BA.2.75.2) are shown above.

On the side of variants of interest (Figure 4), the sixth VOIs spread across late 2020 and early 2021. VOIs were Epsilon confirmed in September 2020, Kappa in October 2020, Iota, Lambda, and Mu identified from November 2020 to January 2021, and Eta in December 2020 (32). These act as storm/variants of the coronavirus, and because of the mutations whose consequences are yet to be fully understood, they are monitored based on case rate upticks, transmission characteristics, case fatalities, ability to evade the immune system, and unusual genome sequences (33). Over time and by far more accumulation of evidence and monitoring, the VOIs may well elevate to VOCs depending on if seriously problematic attributes are verified. As of 2024, new VOIs, including JN.1, were detected in August 2023 and characterized by the S: L455S mutation (34). In the United States, sub-variants of Omicron include KP.2, KP.2.3, KP.3, and KP.3.1.1, which account for 53% of new COVID-19 cases by September 2024 (35). Also, the latest variant, XEC, is on the rise, which is in tandem with the deceleration rate of KP. 3.1.1. The CDC also reports that there will be several minor derivatives of JN.1 by the end of 2024 (36). These VOIs are still closely observed, and their categorization may rise to VOCs based on additional evidence and monitoring results.

Theories about origins and projections for the future

One of the most widely accepted theories about the origin of SARS-CoV-2 is that it emerged through zoonotic spillover (a process in which virus jump from animals to humans either through direct or indirect contact), similar to other coronaviruses like SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV (37). The closest known relative of SARS-CoV-2 is RaTG13, a coronavirus found in horseshoe bats (Rhinolophus affinis), which shares approximately 96% of its genome with the virus responsible for COVID-19 (38). Despite this close relationship, RaTG13 is not identical to SARS-CoV-2, suggesting the possibility of an intermediate host that facilitated the virus's adaptation to humans (39). Pangolins have been proposed as an intermediate host, as pangolin coronaviruses share similarities in their receptor-binding domains (40). However, the exact pathway through which SARS-CoV-2 emerged remains unclear. Wet markets, such as the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan, China, have been implicated in the initial spread of SARS-CoV-2. These markets, where live animals are sold close to humans, create conditions conducive to the spillover of zoonotic pathogens (41). The market was initially thought to be the outbreak's origin, but subsequent research indicated that SARS-CoV-2 was likely circulating in humans before the market-related cases were identified (42).

Projections for the Future of SARS-CoV-2

One of the most widely accepted projections for the future of SARS-CoV-2 is that the virus will become endemic. Examples of endemic viruses include the four human coronaviruses that cause common colds. As population immunity to SARS-CoV-2 increases through vaccination and natural infection, the virus is expected to settle into a more predictable, less severe circulation pattern (43). The future of SARS-CoV-2 is closely tied to its capacity for mutation and the emergence of new variants. The virus's rapid global spread has provided ample opportunities for genetic changes, some of which have led to the emergence of variants with increased transmissibility, immune evasion, or altered disease severity (44). Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron variants have demonstrated the virus's ability to evolve in ways that challenge existing public health strategies. Literature studies such as by described the minimized neutralization of the Delta and Omicron variants by sera from vaccinated individuals, underling the significance of genomic surveillance and updates of the vaccine (45). Future variants could arise with mutations that enable partial or complete escape from vaccine-induced immunity or natural immunity from previous infection. Continued surveillance and rapid adaptation of vaccines, antiviral treatments, and public health measures will be essential in managing these new variants. Developing "universal" coronavirus vaccines that provide broader protection against various variants is also being explored as a long-term strategy (46). Public health strategies must adjust their approach when SARS-CoV-2 becomes endemic. The effectiveness of non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) such as mask-wearing, social distancing, and travel restrictions in reducing virus spread is doubtful for long-term application (47). Attention must move toward specific protective measures targeting at-risk population groups. Global pandemic preparedness needs enhancement to minimize future viral outbreak impacts. The world will enhance its pandemic response by investing in early warning systems, developing international infrastructure, and creating quick vaccine platforms (48).

Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention

Diagnostic tools and issues

COVID-19 diagnostics encompass different techniques that allow for a high detection rate or probability of accurate positivity or negativity. Various rapid diagnostic tests and antigen testing are used to identify some viral proteins rather than the virus through immunochromatography. Nonetheless, antigen tests have low sensitivity, ranging from 50% to 84%, although their specificity is greater than 90% (49). The reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) is the most reputable means of identifying coronavirus (50). Although highly sensitive and specific, the RT-PCR requires expensive equipment and technical expertise (51). High-sensitivity POC (Point of Care) diagnostics such as Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP) increase viral RNA at a constant temperature and produce results within one hour. LAMP has 90-95% sensitivity and 94-100% specificity, making it as effective as RT-PCR for COVID-19 diagnosis (52). The newly developed CRISPR-based diagnostics also identify viral nucleic acids with 93–98% sensitivity and 96-100% specificity (53). Whereas molecular and serological testing identifies the virus or the presence of antibodies, chest CT imaging considers symptoms. In particular, CT scans consistently detect ground-glass opacities and lung consolidations typical of COVID-19 pneumonia with a sensitivity of 80-97%, while specificity was only 60-80% (54). Thus, CT imaging can only be helpful when using other diagnostic correlates to assess the severity and management of infection in hospitalized people. The RT-PCR remains the golden standard test for global diagnosis based on the highest accuracy attained with the antibody (Ab) test, complemented by accessibility-enhanced antigen tests and developed techniques such as LAMP and CRISPR (55). Following the patient pathway also helps with serology and CT imaging. This diverse, sensitive, and specific COVID-19 diagnostic toolbox has been invaluable when managing patients during the pandemic, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Diagnostic Tools for SARS-CoV-2 Detection: Methods, Targets, and Performance

|

Diagnostic Tool |

Method |

Target |

Sensitivity |

Specificity |

Year Developed |

Reference |

|

RT-PCR (Real-Time PCR) |

Detection of viral RNA using reverse transcription and amplification |

Viral RNA (N, E, RdRp genes) |

High (95-99%) |

High (95-100%) |

2020 |

-56 |

|

NGS |

Next-Generation Sequencing |

Whole viral genome |

High |

High |

2020 |

-57 |

|

Virus Isolation |

Cell Culture |

Live virus |

High |

High |

2020 |

-58 |

|

Antigen testing |

Detection of viral proteins using immunochromatography |

Viral antigens (Spike or Nucleocapsid protein) |

Moderate (50-84%) |

High (90-100%) |

2020 |

-59 |

|

LAMP (Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification) |

Amplification of viral RNA at a constant temperature |

Viral RNA (N gene) |

High (90-95%) |

High (94-100%) |

2020 |

-60 |

|

CRISPR-based Diagnostic (e.g., SHERLOCK, DETECTOR) |

CRISPR-Cas system used to detect specific viral RNA sequences |

Viral RNA (N and ORF1ab genes) |

High (93-98%) |

High (96-100%) |

2022 |

-61 |

Vaccine platforms and development

Most COVID-19 vaccines were developed to target the SARS-CoV-2 spike (S) protein, the key viral antigen responsible for host cell entry. Many coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-2, attach to their host cells via the ACE2 receptor and fuse via the spike protein (62). Almost all vaccines target the spike protein or parts of it, most notably the RBD receptor-binding domain in Table 2.

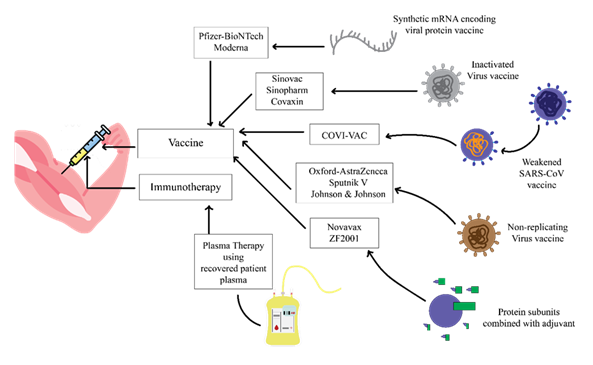

The illustration highlights various approaches to preventing and treating COVID-19, including vaccination to stimulate host immune responses, direct administration of antiviral agents targeting viral replication and entry, use of monoclonal antibodies to neutralize circulating viral particles, convalescent plasma therapy for passive immunity, and small-molecule inhibitors that block key viral or host factors.

The Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines introduce their mRNA encoding the spike protein into cells, and the cells produce the spike protein endogenously and generate immune responses in the form of antibodies (63), (64). Oxford-AstraZeneca and J&J's COVID-19 vaccines use replication-deficient adenoviral vectors to transport DNA containing the spike protein gene into cells so that immunity is generated (65), (66) , (67). Sinovac's CoronaVac, for instance, is an inactivated virus vaccine containing the whole killed SARS-CoV-2 virus to expose the immune system to multiple viral antigens (68). On the same line, Sputnik V applies adenoviral vectors, while Covaxin has inactivated virus forms (69). The Novavax subunit vaccine comprises purified full-length spike protein with an adjuvant to stimulate immune reactions (70). Clinical trials published between 2020 and 2021 have demonstrated good protection against symptomatic and severe disease, with varying efficacy rates. We can conclude that most of the COVID-19 vaccines target the spike protein specially RBD to block the entry of the virus. Platforms may include viral vectors (AstraZeneca), protein subunits (Novavax), mRNA (Pfizer) and inactivated viruses (Sinovac). These vaccines indicated the strong protection against the disease in clinical trials. Further studies on other variant resistance are suggested (Figure 5).

Table 2: Comparison of COVID-19 Vaccines: Receptors, Binding Regions, Mechanisms of Action, and Development Timeline

|

Vaccine Name |

Receptor |

Binding Region |

Mechanism of Action |

Year |

|

Pfizer-BioNTech (BNT162b2) |

ACE2 |

Spike Protein (RBD) |

mRNA encoding spike protein, inducing immune response via spike protein production (71) |

2020 |

|

Moderna (mRNA-1273) |

ACE2 |

Spike Protein (S1 subunit) |

mRNA encoding the spike protein, stimulating the immune system to recognize and combat virus (72). |

2020 |

|

Oxford-AstraZeneca (ChAdOx1) |

ACE2 |

Spike Protein (Full-length) |

Viral vector carrying spike protein gene, stimulating immune response (73). |

2021 |

|

Johnson & Johnson (Ad26.COV2.S) |

ACE2 |

Spike Protein (RBD) |

Adenoviral vector encoding spike protein, stimulating immunity (74). |

2021 |

|

Sinovac (CoronaVac) |

ACE2 |

Whole inactivated virus |

An inactivated virus stimulates the immune system to recognize the entire virus (75). |

2021 |

|

Sputnik V (Gam-COVID-Vac) |

ACE2 |

Spike Protein (Full-length) |

Adenoviral vector encoding spike protein, triggering immune response (76). |

2021 |

|

Covaxin (BBV152) |

ACE2 |

Whole inactivated virus |

Inactivated virus, triggering an immune response against the whole virus (77) |

2021 |

|

Novavax (NVX CoV2373) |

ACE2 |

Spike Protein (Full-length) |

Protein subunit vaccine containing spike protein to induce immune response (78). |

2021 |

|

Valneva (VLA2001) |

ACE 2 |

Spike Protein (Full-length) |

Inactivated virus vaccine, using a whole virus approach for a broader immune response (79). |

2022 |

|

CureVac (CVnCoV) |

ACE 2 |

Spike Protein (Full-length) |

mRNA vaccine encoding full-length spike protein, inducing broad immune protection (80). |

2022 |

Long-Term Problems and Prospects

COVID-19 virus, in particular SARS-CoV-2, has evolved multiple strategies to interact and modulate host immunity and contribute to immune dysregulation and the severity of disease in Table 3. Besides prolonging viral persistence, the following measures result in immune dysfunction, organ failure, and poor disease prognosis, including cytokine storms, lymphopenia, and multiorgan failure (81). SARS-CoV-2 has shown extremely high efficiency in establishing several factors for inhibiting host interferon production and interferon signaling. IFN-α, IFN-β, and IFN-λ are the important CoV-2 down-regulates the cell signaling pathways involved in the synthesis and expression of interferons. Accessory proteins nsp1, nsp6, and nsp13, sub-genomic non-structural proteins, inhibit signaling through those receptors RIG-I and MDA5, which act on interferon genes. Likewise, the SARS-CoV-2 ORF6 protein inhibits STAT1 signaling, so interferon cannot do its antiviral function when interacting with its receptor (82). SARS-CoV-2 suppresses interferon and its signaling pathway transduction via these two combined mechanisms of action that affect the host's antiviral signaling sequence (83). TLR3 and TLR7 usually are in charge of identifying viral RNA and notification for an immune response. However, SARS-CoV-2 has seemed to evade these receptors, enabling it to penetrate the host's body cells efficiently (84). Primarily, the virus blocks the proteins required to activate TLR3 and TLR7 to alert immune system components of its viral RNA. The low levels of TLR3 and TLR7 signaling lead to small amounts of the proinflammatory cytokines and antiviral that should counteract viral replication and its spread (85).

The intrinsic immune system, along with the T lymphocytes and B lymphocytes, is again directly affected by SARS-CoV-2 so as not to generate an effective immunogenic response(86). Specifically, SARS-CoV-2, which leads to COVID-19, has been shown to significantly skew T-cell functions that are otherwise central to viral clearance. One such effect leads to lymphopenia or low T-cell levels (87). This is made possible by the ability to infect T cells, kill them, and enhance cell death, preferably through apoptosis, and increase T cell exhaustion. T cell exhaustion describes a condition in which T cells become rarer valuable tools to fight viruses in the body, and the cells' ability to replicate and kill virus-infected cells is also reduced. SARS-CoV-2 also upregulates semi-permissive markers of PD-1 and TIM-3 receptors on the surface of exhausted T cells and hinders T cell activity through one or several inhibitory signaling cascades (88). Furthermore, the virus appears to shift the T helper cell to a Th2 dominant type, which is characteristic of responses against extracellular parasites and is insufficient to lead to efficient viral clearance. Subsequent studies have also demonstrated that the antibodies produced may facilitate the inoculation of further immune cells with the virus through ADE (89). There are complex glycans on the spiky (S) protein coming out of the envelope of SARS-CoV-2 and out of the outer layer of the virus; some are very branched. Such a kind of post-translational modification is significant because it camouflages specific regions of the spike protein from the host's immune system (90). Similarly, while the glycans cover some area of the Spike that, if uncovered, would trigger the production of neutralizing antibodies, the molecules cover the position of immunogenic sites from antibodies that recognize them (91). Therefore, glycosylation plays the role of the protective layer, preventing the later recognition and destruction of viral epitopes in the case of the SARS-CoV-2 virus by the host's immune system (92). The shield level provided by glycosylation is one of the modalities through which SARS-CoV-2 improves infection outcomes. This looks more like a rigid barrier that has persisted to be a challenge in finding a vaccine or therapy for COVID-19 (93).

Table 3: The immune dysfunction and evasion mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2

Discussion

The ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, caused by SARS-CoV-2, continues to serve as a dynamic model for the study of emerging viral pathogens, their evolutionary trajectories, and the challenges of public health response. Over the past several years, a massive research effort has rapidly uncovered critical aspects of the molecular virology, cell biology, immunopathology, and epidemiology of SARS-CoV-2. However, persistent viral evolution, heterogeneous clinical outcomes, and recurring waves of infection demonstrate that our understanding and control measures must continuously adapt(107). The receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the spike protein has become a critical target for neutralizing antibodies and vaccine development. Recent studies have also highlighted the conformational flexibility of the spike protein, which facilitates both receptor engagement (primarily ACE2) and evasion from host immune responses through mutations and glycan shielding. The identification of auxiliary host receptors and co-factors including NRP1, CD147, and TMPRSS2 has further revealed that SARS-CoV-2 exploits multiple cellular pathways for entry, endosomal trafficking, and membrane fusion. Notably, TMPRSS2-mediated S protein priming at the cell surface provides a rapid route for viral fusion, bypassing endosomal restriction mechanisms and enabling efficient cell-to-cell transmission(108). Targeting these host factors with inhibitors or monoclonal antibodies thus represents a promising therapeutic avenue, especially as viral variants continue to emerge with altered receptor binding or protease sensitivity(109).

In addition to the spike protein, the envelope (E), membrane (M), and nucleocapsid (N) proteins contribute to virion stability, genome packaging, and immune evasion. For instance, the E protein participates in assembly and budding, while the N protein not only protects the viral genome but also modulates host cell stress and innate immune pathways. These multifaceted roles highlight the importance of broadening antiviral strategies beyond spike-targeted approaches to include non-spike structural and accessory proteins, which may be less susceptible to antigenic drift(110). A defining characteristic of SARS-CoV-2 is its remarkable genetic plasticity, exemplified by the emergence of multiple variants of concern (VOCs) and variants of interest (VOIs). These variants have introduced new constellations of spike mutations, many of which enhance ACE2 binding, confer resistance to neutralizing antibodies, or alter viral transmissibility and pathogenicity. The global spread of the Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta, and Omicron lineages, followed by successive Omicron subvariants (e.g., BA.1, BA.2, BA.5), underscores the adaptive capacity of the virus under selective pressure from population immunity and vaccination campaigns. Of particular concern are mutations in the RBD and N-terminal domain that reduce the effectiveness of previously elicited neutralizing antibodies and, in some cases, impair vaccine efficacy(111).

Conclusion

The complexity of SARS-CoV-2 transmission worldwide has expedited scientific progress in understanding viral behavior. This study examines the virus structure, its entry, interactions with the host cells, and genomic organization, providing details about its adaptability and infectivity. The key roles of the structural components of the virus include the spike protein, envelope, membrane components, and nucleocapsid proteins, underlining the complications of the viral replication and immune suppression methods. The continued appearance of the variants of concern and variants of interest also pinpoint the need for genomic surveillance.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare there is no competing interest.

Funding resources

Anhui Provincial Natural Science Foundation Project “In Vivo Induction and Regulation of Anti-HIV Broad-spectrum Neutralizing Antibodies” (2208085MH260).

Author Contribution

Muhammad Waqas Nasir has conceptualized, design the project, investigated the data, resource collection, data curation and formal analysis draft manuscript writing and editing the manuscript. Wangjing and Xiangyu Zhang have investigated the data, resource collection, Citation, Formal analysis and draft writing and contributed equally to the manuscript. Mahir Azmal has investigated the data, reviewed the draft writing and citation. Ajit Ghosh contributed to reviewed and edited manuscripts, Yong Gao conceived, designed, and administered the project, supervised, drafted manuscript writing, managed the funding and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All the authors read the final version of the manuscript.

References

- Sharma R, Khokhar D, Gupta B, Saxena P, Ghosh KK, Geda AK, et al. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus -2 (SARS-CoV-2): A Review on Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, and Investigational Therapeuti. Curr Med Chem. 2021;28(41):8559–94.

- Antony P, Vijayan R. Role of SARS-CoV-2 and ACE2 variations in COVID-19. Biomed J. 2021 June 1;44(3):235–44.

- Hoffmann M, Kleine-Weber H, Schroeder S, Krüger N, Herrler T, Erichsen S, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry Depends on ACE2 and TMPRSS2 and Is Blocked by a Clinically Proven Protease Inhibitor. Cell. 2020 Apr 16;181(2):271-280.e8.

- Jackson CB, Farzan M, Chen B, Choe H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022 Jan;23(1):3–20.

- Malik JR, Acharya A, Avedissian SN, Byrareddy SN, Fletcher CV, Podany AT, et al. ACE-2, TMPRSS2, and Neuropilin-1 Receptor Expression on Human Brain Astrocytes and Pericytes and SARS-CoV-2 Infection Kinetics. Int J Mol Sci. 2023 May 11;24(10):8622.

- Hadi R, Poddar A, Sonnaila S, Bhavaraju VSM, Agrawal S. Advancing CRISPR-Based Solutions for COVID-19 Diagnosis and Therapeutics. Cells. 2024 Oct 30;13(21):1794.

- Lafi Z, Ata ,Tha’er, and Asha S. CRISPR in clinical diagnostics: bridging the gap between research and practice. Bioanalysis. 2025 Feb 16;17(4):281–90.

- Candido KL, Eich CR, de Fariña LO, Kadowaki MK, da Conceição Silva JL, Maller A, et al. Spike protein of SARS-CoV-2 variants: a brief review and practical implications. Braz J Microbiol Publ Braz Soc Microbiol. 2022 Sept;53(3):1133–57.

- Charles J, McCann N, Ploplis VA, Castellino FJ. Spike protein receptor-binding domains from SARS-CoV-2 variants of interest bind human ACE2 more tightly than the prototype spike protein. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2023 Jan 22;641:61–6.

- Liu S, Xiao G, Chen Y, He Y, Niu J, Escalante CR, et al. Interaction between heptad repeat 1 and 2 regions in spike protein of SARS-associated coronavirus: implications for virus fusogenic mechanism and identification of fusion inhibitors. Lancet Lond Engl. 2004 Mar 20;363(9413):938–47.

- Beaudoin CA, Hamaia SW, Huang CLH, Blundell TL, Jackson AP. Can the SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Bind Integrins Independent of the RGD Sequence? Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2021;11:765300.

- Fehr AR, Perlman S. Coronaviruses: an overview of their replication and pathogenesis. Methods Mol Biol Clifton NJ. 2015;1282:1–23.

- Lamers MM, Haagmans BL. SARS-CoV-2 pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2022 May;20(5):270–84.

- Neuman BW, Kiss G, Kunding AH, Bhella D, Baksh MF, Connelly S, et al. A structural analysis of M protein in coronavirus assembly and morphology. J Struct Biol. 2011 Apr;174(1):11–22.

- Bai Z, Cao Y, Liu W, Li J. The SARS-CoV-2 Nucleocapsid Protein and Its Role in Viral Structure, Biological Functions, and a Potential Target for Drug or Vaccine Mitigation. Viruses. 2021 June 10;13(6):1115.

- Zhang Z, Nomura N, Muramoto Y, Ekimoto T, Uemura T, Liu K, et al. Structure of SARS-CoV-2 membrane protein essential for virus assembly. Nat Commun. 2022 Aug 5;13(1):4399.

- Wu C rong, Yin W chao, Jiang Y, Xu HE. Structure genomics of SARS-CoV-2 and its Omicron variant: drug design templates for COVID-19. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2022 Dec;43(12):3021–33.

- Yu S, Hu H, Ai Q, Bai R, Ma K, Zhou M, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike-Mediated Entry and Its Regulation by Host Innate Immunity. Viruses. 2023 Feb 27;15(3):639.

- Jackson CB, Farzan M, Chen B, Choe H. Mechanisms of SARS-CoV-2 entry into cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2022 Jan;23(1):3–20.

- Yelland T, Djordjevic S. Crystal Structure of the Neuropilin-1 MAM Domain: Completing the Neuropilin-1 Ectodomain Picture. Struct Lond Engl 1993. 2016 Nov 1;24(11):2008–15.

- Roth L, Nasarre C, Dirrig-Grosch S, Aunis D, Crémel G, Hubert P, et al. Transmembrane Domain Interactions Control Biological Functions of Neuropilin-1. Mol Biol Cell. 2008 Feb;19(2):646–54.

- Li F. Structure, Function, and Evolution of Coronavirus Spike Proteins. Annu Rev Virol. 2016 Sept 29;3(1):237–61.

- Modrow S, Falke D, Truyen U, Schätzl H. Viruses with Single-Stranded, Positive-Sense RNA Genomes. Mol Virol. 2013 Aug 12;185–349.

- SENAPATI S, BANERJEE P, BHAGAVATULA S, KUSHWAHA PP, KUMAR S. Contributions of human ACE2 and TMPRSS2 in determining host–pathogen interaction of COVID-19. J Genet. 2021;100(1):12.

- Nejat R, Torshizi MF, Najafi DJ. S Protein, ACE2 and Host Cell Proteases in SARS-CoV-2 Cell Entry and Infectivity; Is Soluble ACE2 a Two Blade Sword? A Narrative Review. Vaccines. 2023 Jan 17;11(2):204.

- Markov PV, Ghafari M, Beer M, Lythgoe K, Simmonds P, Stilianakis NI, et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023 June;21(6):361–79.

- Hill V, Plessis LD, Peacock TP, Aggarwal D, Colquhoun R, Carabelli AM, et al. The origins and molecular evolution of SARS-CoV-2 lineage B.1.1.7 in the UK. Virus Evol. 2022 Sept 21;8(2):veac080.

- Pérez P, Albericio G, Astorgano D, Flores S, Sánchez-Corzo C, Sánchez-Cordón PJ, et al. Preclinical immune efficacy against SARS-CoV-2 beta B.1.351 variant by MVA-based vaccine candidates. Front Immunol. 2023 Dec 12;14:1264323.

- Tao K, Tzou PL, Nouhin J, Gupta RK, de Oliveira T, Kosakovsky Pond SL, et al. The biological and clinical significance of emerging SARS-CoV-2 variants. Nat Rev Genet. 2021 Dec;22(12):757–73.

- Sgorlon G, Roca TP, Passos-Silva AM, Custódio MGF, Queiroz JA da S, Silva ALF da, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein Mutations in Different Variants: A Comparison Between Vaccinated and Unvaccinated Population in Western Amazonia. Bioinforma Biol Insights. 2023 Jan 1;17:11779322231186477.

- Halfmann PJ, Iida S, Iwatsuki-Horimoto K, Maemura T, Kiso M, Scheaffer SM, et al. SARS-CoV-2 Omicron virus causes attenuated disease in mice and hamsters. Nature. 2022 Mar;603(7902):687–92.

- Bareggi R, Bratina F, Grill V, Narducci P, Martelli AM. Atypical isoenzymes of PKC-iota, -lambda, -mu: relative distribution in mouse foetal and neonatal organs. Ital J Anat Embryol Arch Ital Anat Ed Embriologia. 1998;103(4):127–43.

- Mahilkar S, Agrawal S, Chaudhary S, Parikh S, Sonkar SC, Verma DK, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variants: Impact on biological and clinical outcome. Front Med. 2022;9:995960.

- Li L, Shi K, Gu Y, Xu Z, Shu C, Li D, et al. Spike structures, receptor binding, and immune escape of recently circulating SARS-CoV-2 Omicron BA.2.86, JN.1, EG.5, EG.5.1, and HV.1 sub-variants. Struct Lond Engl 1993. 2024 Aug 8;32(8):1055-1067.e6.

- Cobar O, Cobar S. Omicron Variants World Prevalence, 169 WHO COVID-19 Epidemiological Update, ECDC Communicable Disease Threat Report, and CDC COVID Data Tracker Review. 2024.

- Ma KC. Genomic Surveillance for SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Circulation of Omicron XBB and JN.1 Lineages — United States, May 2023–September 2024. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep [Internet]. 2024 [cited 2025 June 26];73. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/73/wr/mm7342a1.htm

- Cui X, Wang Y, Zhai J, Xue M, Zheng C, Yu L. Future trajectory of SARS-CoV-2: Constant spillover back and forth between humans and animals. Virus Res. 2023 Apr 15;328:199075.

- Alkhovsky S, Lenshin S, Romashin A, Vishnevskaya T, Vyshemirsky O, Bulycheva Y, et al. SARS-like Coronaviruses in Horseshoe Bats (Rhinolophus spp.) in Russia, 2020. Viruses. 2022 Jan 9;14(1):113.

- Hu B, Guo H, Zhou P, Shi ZL. Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021 Mar;19(3):141–54.

- Liu P, Jiang JZ, Wan XF, Hua Y, Li L, Zhou J, et al. Are pangolins the intermediate host of the 2019 novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2)? PLoS Pathog. 2020 May;16(5):e1008421.

- Erratum for the Research Article “The Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan was the early epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic” by M. Worobey et al. Science. 2024 Mar 15;383(6688):eadp1133.

- Hao YJ, Wang YL, Wang MY, Zhou L, Shi JY, Cao JM, et al. The origins of COVID-19 pandemic: A brief overview. Transbound Emerg Dis. 2022 Nov;69(6):3181–97.

- Wang X, Li J, Liu H, Hu X, Lin Z, Xiong N. SARS-CoV-2 versus Influenza A Virus: Characteristics and Co-Treatments. Microorganisms. 2023 Mar;11(3):580.

- Carabelli AM, Peacock TP, Thorne LG, Harvey WT, Hughes J, COVID-19 Genomics UK Consortium, et al. SARS-CoV-2 variant biology: immune escape, transmission and fitness. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023 Mar;21(3):162–77.

- Zabidi NZ, Liew HL, Farouk IA, Puniyamurti A, Yip AJW, Wijesinghe VN, et al. Evolution of SARS-CoV-2 Variants: Implications on Immune Escape, Vaccination, Therapeutic and Diagnostic Strategies. Viruses. 2023 Apr 10;15(4):944.

- Wang G, Verma AK, Shi J, Guan X, Meyerholz DK, Bu F, et al. Universal subunit vaccine protects against multiple SARS-CoV-2 variants and SARS-CoV. Npj Vaccines. 2024 July 25;9(1):133.

- Francis NA, Becque T, Willcox M, Hay AD, Lown M, Clarke R, et al. Non-pharmaceutical interventions and risk of COVID-19 infection: survey of U.K. public from November 2020 - May 2021. BMC Public Health. 2023 Feb 24;23(1):389.

- Byrne P, Harding-Edgar L, Pollock AM. SARS-CoV-2: public health measures for managing the transition to endemicity. J R Soc Med. 2022 May 1;115(5):165–8.

- Nasir MW, Gao Y. Advances in KSHV Research: Molecular Pathogenesis, Immune Evasion, and Evolving Therapeutic Horizon. J Med Virol. 2025 Nov;97(11):e70695.

- Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, Molenkamp R, Meijer A, Chu DK, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill Bull Eur Sur Mal Transm Eur Commun Dis Bull. 2020 Jan;25(3):2000045.

- Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, Li X, Yang B, Song J, et al. A Novel Coronavirus from Patients with Pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med. 2020 Feb 20;382(8):727–33.

- Nagura-Ikeda M, Imai K, Tabata S, Miyoshi K, Murahara N, Mizuno T, et al. Clinical Evaluation of Self-Collected Saliva by Quantitative Reverse Transcription-PCR (RT-qPCR), Direct RT-qPCR, Reverse Transcription-Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification, and a Rapid Antigen Test To Diagnose COVID-19. J Clin Microbiol. 2020 Aug 24;58(9):e01438-20.

- Javalkote VS, Kancharla N, Bhadra B, Shukla M, Soni B, Sapre A, et al. CRISPR-based assays for rapid detection of SARS-CoV-2. Methods San Diego Calif. 2022 July;203:594–603.

- Ai T, Yang Z, Hou H, Zhan C, Chen C, Lv W, et al. Correlation of Chest CT and RT-PCR Testing for Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) in China: A Report of 1014 Cases. Radiology. 2020 Aug;296(2):E32–40.

- Kevadiya BD, Machhi J, Herskovitz J, Oleynikov MD, Blomberg WR, Bajwa N, et al. Diagnostics for SARS-CoV-2 Infections. Nat Mater. 2021 May;20(5):593–605.

- Dutta D, Naiyer S, Mansuri S, Soni N, Singh V, Bhat KH, et al. COVID-19 Diagnosis: A Comprehensive Review of the RT-qPCR Method for Detection of SARS-CoV-2. 2022 June 20;12(6):1503.

- Satam H, Joshi K, Mangrolia U, Waghoo S, Zaidi G, Rawool S, et al. Next-Generation Sequencing Technology: Current Trends and Advancements. Biology. 2023 July 13;12(7):997.

- Sykes JE, Rankin SC. Isolation in Cell Culture. Canine Feline Infect Dis. 2014;2–9.

- Kyosei Y, Yamura S, Namba M, Yoshimura T, Watabe S, Ito E. Antigen tests for COVID-19. Biophys Physicobiology. 2021 Feb 10;18:28–39.

- Augustine R, Hasan A, Das S, Ahmed R, Mori Y, Notomi T, et al. Loop-Mediated Isothermal Amplification (LAMP): A Rapid, Sensitive, Specific, and Cost-Effective Point-of-Care Test for Coronaviruses in the Context of COVID-19 Pandemic. Biology. 2020 July 22;9(8):182.

- Fang L, Yang L, Han M, Xu H, Ding W, Dong X. CRISPR-cas technology: A key approach for SARS-CoV-2 detection. Front Bioeng Biotechnol [Internet]. 2023 Apr 12 [cited 2025 June 26];11. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/bioengineering-and-biotechnology/articles/10.3389/fbioe.2023.1158672/full

- Soraci L, Lattanzio F, Soraci G, Gambuzza ME, Pulvirenti C, Cozza A, et al. COVID-19 Vaccines: Current and Future Perspectives. Vaccines. 2022 Apr 13;10(4):608.

- Polack FP, Thomas SJ, Kitchin N, Absalon J, Gurtman A, Lockhart S, et al. Safety and Efficacy of the BNT162b2 mRNA Covid-19 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2020 Dec 31;383(27):2603–15.

- Baden LR, El Sahly HM, Essink B, Kotloff K, Frey S, Novak R, et al. Efficacy and Safety of the mRNA-1273 SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine. N Engl J Med. 2021 Feb 4;384(5):403–16.

- Voysey M, Clemens SAC, Madhi SA, Weckx LY, Folegatti PM, Aley PK, et al. Safety and efficacy of the ChAdOx1 nCoV-19 vaccine (AZD1222) against SARS-CoV-2: an interim analysis of four randomised controlled trials in Brazil, South Africa, and the UK. The Lancet. 2021 Jan 9;397(10269):99–111.

- Sadoff J, Gray G, Vandebosch A, Cárdenas V, Shukarev G, Grinsztejn B, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Single-Dose Ad26.COV2.S Vaccine against Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2021 June 10;384(23):2187–201.

- Zhang Y, Zeng G, Pan H, Li C, Hu Y, Chu K, et al. Safety, tolerability, and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in healthy adults aged 18-59 years: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 1/2 clinical trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 Feb;21(2):181–92.

- Logunov DY, Dolzhikova IV, Shcheblyakov DV, Tukhvatulin AI, Zubkova OV, Dzharullaeva AS, et al. Safety and efficacy of an rAd26 and rAd5 vector-based heterologous prime-boost COVID-19 vaccine: an interim analysis of a randomised controlled phase 3 trial in Russia. The Lancet. 2021 Feb 20;397(10275):671–81.

- Ella R, Reddy S, Jogdand H, Sarangi V, Ganneru B, Prasad S, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine, BBV152: interim results from a double-blind, randomised, multicentre, phase 2 trial, and 3-month follow-up of a double-blind, randomised phase 1 trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021 July 1;21(7):950–61.

- Shinde S, Lee LH, Chu T. Inhibition of Biofilm Formation by the Synergistic Action of EGCG-S and Antibiotics. Antibiot Basel Switz. 2021 Jan 21;10(2):102.

- Cosenza LC, Marzaro G, Zurlo M, Gasparello J, Zuccato C, Finotti A, et al. Inhibitory effects of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and BNT162b2 vaccine on erythropoietin-induced globin gene expression in erythroid precursor cells from patients with β-thalassemia. Exp Hematol [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2025 June 26];129. Available from: https://www.exphem.org/article/S0301-472X(23)01761-7/fulltext

- Trougakos IP, Terpos E, Alexopoulos H, Politou M, Paraskevis D, Scorilas A, et al. Adverse effects of COVID-19 mRNA vaccines: the spike hypothesis. Trends Mol Med. 2022 July;28(7):542–54.

- Pack SM, Peters PJ. SARS-CoV-2–Specific Vaccine Candidates; the Contribution of Structural Vaccinology. Vaccines. 2022 Feb 3;10(2):236.

- Bos R, Rutten L, van der Lubbe JEM, Bakkers MJG, Hardenberg G, Wegmann F, et al. Ad26 vector-based COVID-19 vaccine encoding a prefusion-stabilized SARS-CoV-2 Spike immunogen induces potent humoral and cellular immune responses. Npj Vaccines. 2020 Sept 28;5(1):91.

- Hu L, Sun J, Wang Y, Tan D, Cao Z, Gao L, et al. A Review of Inactivated COVID-19 Vaccine Development in China: Focusing on Safety and Efficacy in Special Populations. Vaccines. 2023 May 31;11(6):1045.

- Cornejo A, Franco C, Rodriguez-Nuñez M, García A, Belisario I, Mayora S, et al. Humoral Immunity across the SARS-CoV-2 Spike after Sputnik V (Gam-COVID-Vac) Vaccination. Antibodies. 2024 May 11;13(2):41.

- Ahmed TI, Rishi S, Irshad S, Aggarwal J, Happa K, Mansoor S. Inactivated vaccine Covaxin/BBV152: A systematic review. Front Immunol. 2022 Aug 9;13:863162.

- Tian JH, Patel N, Haupt R, Zhou H, Weston S, Hammond H, et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike glycoprotein vaccine candidate NVX-CoV2373 immunogenicity in baboons and protection in mice. Nat Commun. 2021 Jan 14;12:372.

- Galhaut M, Lundberg U, Marlin R, Schlegl R, Seidel S, Bartuschka U, et al. Immunogenicity and efficacy of VLA2001 vaccine against SARS-CoV-2 infection in male cynomolgus macaques. Commun Med. 2024 Apr 3;4(1):62.

- Lenart K, Hellgren F, Ols S, Yan X, Cagigi A, Cerveira RA, et al. A third dose of the unmodified COVID-19 mRNA vaccine CVnCoV enhances quality and quantity of immune responses. Mol Ther Methods Clin Dev. 2022 Oct 6;27:309–23.

- Li X, Mi Z, Liu Z, Rong P. SARS-CoV-2: pathogenesis, therapeutics, variants, and vaccines. Front Microbiol [Internet]. 2024 June 13 [cited 2025 June 26];15. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/microbiology/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2024.1334152/full

- Vazquez C, Swanson SE, Negatu SG, Dittmar M, Miller J, Ramage HR, et al. SARS-CoV-2 viral proteins NSP1 and NSP13 inhibit interferon activation through distinct mechanisms. PloS One. 2021;16(6):e0253089.

- Samuel CE. Interferon at the crossroads of SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19 disease. J Biol Chem. 2023 Aug;299(8):104960.

- Bortolotti D, Gentili V, Rizzo S, Schiuma G, Beltrami S, Strazzabosco G, et al. TLR3 and TLR7 RNA Sensor Activation during SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Microorganisms. 2021 Aug 26;9(9):1820.

- Sartorius R, Trovato M, Manco R, D’Apice L, De Berardinis P. Exploiting viral sensing mediated by Toll-like receptors to design innovative vaccines. Npj Vaccines. 2021 Oct 28;6(1):127.

- Wang J, Ni S, Chen Q, Wang C, Liu H, Huang L, et al. Discovery of a Novel Public Antibody Lineage Correlated With Inactivated SARS-CoV-2 Vaccine and the Resultant Neutralization Activity. J Med Virol. 2024;96(12):e70073.

- Shrotri M, van Schalkwyk MCI, Post N, Eddy D, Huntley C, Leeman D, et al. T cell response to SARS-CoV-2 infection in humans: A systematic review. PloS One. 2021;16(1):e0245532.

- Yi JS, Cox MA, Zajac AJ. T-cell exhaustion: characteristics, causes and conversion. Immunology. 2010 Apr;129(4):474–81.

- Wen J, Cheng Y, Ling R, Dai Y, Huang B, Huang W, et al. Antibody-dependent enhancement of coronavirus. Int J Infect Dis IJID Off Publ Int Soc Infect Dis. 2020 Nov;100:483–9.

- Zhao X, Chen H, Wang H. Glycans of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein in Virus Infection and Antibody Production. Front Mol Biosci. 2021;8:629873.

- Newby ML, Fogarty CA, Allen JD, Butler J, Fadda E, Crispin M. Variations within the Glycan Shield of SARS-CoV-2 Impact Viral Spike Dynamics. J Mol Biol. 2023 Feb 28;435(4):167928.

- Aloor A, Aradhya R, Venugopal P, Gopalakrishnan Nair B, Suravajhala R. Glycosylation in SARS-CoV-2 variants: A path to infection and recovery. Biochem Pharmacol. 2022 Dec;206:115335.

- Huang HY, Liao HY, Chen X, Wang SW, Cheng CW, Shahed-Al-Mahmud M, et al. Vaccination with SARS-CoV-2 spike protein lacking glycan shields elicits enhanced protective responses in animal models. Sci Transl Med. 2022 Apr 6;14(639):eabm0899.

- Beyer DK, Forero A. Mechanisms of Antiviral Immune Evasion of SARS-CoV-2. J Mol Biol. 2022 Mar 30;434(6):167265.

- Lester SN, Li K. Toll-Like Receptors in Antiviral Innate Immunity. J Mol Biol. 2014 Mar 20;426(6):1246–64.

- Varghese PM, Murugaiah V, Beirag N, Temperton N, Khan HA, Alrokayan SH, et al. C4b Binding Protein Acts as an Innate Immune Effector Against Influenza A Virus. Front Immunol. 2020;11:585361.

- Grywalska E, Pasiarski M, Góźdź S, Roliński J. Immune-checkpoint inhibitors for combating T-cell dysfunction in cancer. OncoTargets Ther. 2018 Oct 4;11:6505–24.

- Qi H, Liu B, Wang X, Zhang L. The humoral response and antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Immunol. 2022 July;23(7):1008–20.

- Grant OC, Montgomery D, Ito K, Woods RJ. Analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein glycan shield reveals implications for immune recognition. Sci Rep. 2020 Sept 14;10(1):14991.

- Mengist HM, Kombe Kombe AJ, Mekonnen D, Abebaw A, Getachew M, Jin T. Mutations of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein: Implications on immune evasion and vaccine-induced immunity. Semin Immunol. 2021 June;55:101533.

- Karki R, Kanneganti TD. The ‘Cytokine Storm’: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic prospects. Trends Immunol. 2021 Aug;42(8):681–705.

- Wang Z, Zhang S, Xiao Y, Zhang W, Wu S, Qin T, et al. NLRP3 Inflammasome and Inflammatory Diseases. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2020 Feb 17;2020:4063562.

- Liang S, Wu YS, Li DY, Tang JX, Liu HF. Autophagy in Viral Infection and Pathogenesis. Front Cell Dev Biol [Internet]. 2021 Oct 15 [cited 2025 June 26];9. Available from: https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/cell-and-developmental-biology/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.766142/full

- Teow SY, Nordin AC, Ali SA, Khoo ASB. Exosomes in Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type I Pathogenesis: Threat or Opportunity? Adv Virol. 2016;2016:9852494.

- Yuan C, Ma Z, Xie J, Li W, Su L, Zhang G, et al. The role of cell death in SARS-CoV-2 infection. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023 Sept 20;8:357.

- Yu P, Zhang X, Liu N, Tang L, Peng C, Chen X. Pyroptosis: mechanisms and diseases. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2021 Mar 29;6(1):128.

- Markov PV, Ghafari M, Beer M, Lythgoe K, Simmonds P, Stilianakis NI, et al. The evolution of SARS-CoV-2. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023 June;21(6):361–79.

- Yang H, Rao Z. Structural biology of SARS-CoV-2 and implications for therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2021 Nov;19(11):685–700.

- Mahajan S, Choudhary S, Kumar P, Tomar S. Antiviral strategies targeting host factors and mechanisms obliging +ssRNA viral pathogens. Bioorg Med Chem. 2021 Sept 15;46:116356.

- Surjit M, Liu B, Kumar P, Chow VTK, Lal SK. The nucleocapsid protein of the SARS coronavirus is capable of self-association through a C-terminal 209 amino acid interaction domain. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004 May 14;317(4):1030–6.

- Cocherie T, Zafilaza K, Leducq V, Marot S, Calvez V, Marcelin AG, et al. Epidemiology and Characteristics of SARS-CoV-2 Variants of Concern: The Impacts of the Spike Mutations. Microorganisms. 2023 Jan;11(1):30.

Impact Factor: * 3.5

Impact Factor: * 3.5 Acceptance Rate: 71.36%

Acceptance Rate: 71.36%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks