Do Digestive Bacteria Suffer from Oxidative Stress: A Study on Ruminal Bacteria

Muhammad Kaleem1, Yves Farizon1, Géraldine Pascal1, Tiphaine Blanchard1, Laurent Cauquil1, Sylvie Combes1, Denys Durand2, Francis Enjalbert1, Djamila Ali Haimoud-Lekhal1,3, Annabelle Meynadier1*

1GenPhySE, Université de Toulouse, INRAE, ENVT, 31326, Castanet Tolosan, France

2INRAE, VetAgro Sup, Université Clermont Auvergne, 63122 Saint-Genès-Champanelle, France

3INP-Purpan, Toulouse, France

*Corresponding Author: Annabelle Meynadier, GenPhySE, Université de Toulouse, INRAE, EI PURPAN, Toulouse, France

Received: 05 July 2025; Accepted: 15 July 2025; Published: 04 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Background: Heating oils and oilseeds results in oxidized fatty acids with potential antimicrobial properties that could affect digestive microbiota, and therefore health.

Objectives: The objectives of this study were to explore the effect of lipid oxidation products on digestive bacteria using rumen content culture.

Methods: A long-term in vitro study was conducted to check the effects of one hydroperoxide, 13OOH cis-9,trans-11-C18:2 (13HPOD), and two aldehydes, hexanal and trans-2,trans-4-decadienal (T2T4D), on rumen bacteria and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. Rumen fluid was incubated with one of the three oxidation products for 54 h or 102 h. Controls without oxidation products were also incubated.

Results: The bacterial community was highly affected by T2T4D, in particular the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio and the relative abundance of the Bacteroidales S24-7 group family, leading to an alteration of fermentation responsible for a higher final pH than those in control cultures, and a diminution of SOD activity. Other oxidative products did not affect SOD activity, as well as hexanal did not modify the bacterial community compared to that of the control.

Conclusion: The modification of the ruminal bacterial community by T2T4D represents a potential risk for the health of its host. Oxidative stress needs to be investigated in digestive ecosystems.

DOI: 10.26502/jfsnr.2642-110000185

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Heating oils and oilseeds results in oxidized fatty acids with potential antimicrobial properties that could affect digestive microbiota, and therefore health.

Objectives: The objectives of this study were to explore the effect of lipid oxidation products on digestive bacteria using rumen content culture.

Methods: A long-term in vitro study was conducted to check the effects of one hydroperoxide, 13OOH cis-9,trans-11-C18:2 (13HPOD), and two aldehydes, hexanal and trans-2,trans-4-decadienal (T2T4D), on rumen bacteria and superoxide dismutase (SOD) activity. Rumen fluid was incubated with one of the three oxidation products for 54 h or 102 h. Controls without oxidation products were also incubated.

Results: The bacterial community was highly affected by T2T4D, in particular the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio and the relative abundance of the Bacteroidales S24-7 group family, leading to an alteration of fermentation responsible for a higher final pH than those in control cultures, and a diminution of SOD activity. Other oxidative products did not affect SOD activity, as well as hexanal did not modify the bacterial community compared to that of the control.

Conclusion: The modification of the ruminal bacterial community by T2T4D represents a potential risk for the health of its host. Oxidative stress needs to be investigated in digestive ecosystems.

Keywords

<p>Rumen; Microbiota, Hydroperoxide, Aldehyde, Lipid oxidation</p>

Article Details

Introduction

When heated, unsaturated fats undergo peroxidation, leading to lipid oxidation products (LOPs) formation in three steps [1]. The first and second steps form hydroperoxides (HPODs), while the last step mainly forms aldehydes involved in oxidative stress.

Oxidative stress is known to alter health. In humans, HPODs, and mainly their stable reduced forms, hydroxyacids, increase during oxidative stress generated by diseases such as diabetes or atherosclerosis [2]. As illustration, LOPs of linoleic acid (LA), i.e., 9- and 13-hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids, are the most abundant in atherosclerotic lesions and in low-density lipoproteins (LDL) in patients.

Impacts of oxidative stress on health are also observed in livestock [3].

For example, in dairy cows, lipid peroxidation may reduce the reproduction capacity (inactivation of steroidogenic enzymes, retained placenta, udder oedema or milk fever) and impair immunological responses [4].

In humans, as well as in animals, existing data concern more particularly tissue LOP. Few studies have explored the effects of LOPs on the gut microbiota. As far as we know, there has been no study on humans, and only four studies on animals show a modification of digestive microbiota and its activities by pure LOPs or heated fat, three of them in vitro on rumen contents [5-7] and one on broiler’s gut [8]. Besides, recent work carried out in dairy cows shows that antioxidants, vitamin E, are also powerful modulators of the ruminal microbiota [9]. Although they remain limited these studies suggest a potential action of LOPs on the digestive microbiota.

Indeed, LOPs could act on bacteria: peroxides affect anaerobes [10], and aldehydes have antimicrobial effects that increase with their chain length [11] and their degree of unsaturation [12]. On the other hand, several bacteria respond to oxidative stress in the digestive tract through the synthesis of superoxide dismutase (SOD), including ruminal bacteria [13,14], which could lead the host to be less sensitive to food LOPs.

A previous in vitro study using short-term (6 h and 24 h) batch cultures did not show any significant effects of LOPs on the rumen microbiota, despite the great effects of HPODs and long-chain unsaturated aldehydes on lipid rumen metabolism [6]. Indeed, changes in the rumen microbiota could be too slow to be exhibited with such short incubation times. Moreover, inactivated bacterial DNA is detected as efficiently as DNA from active bacteria, so a bacteriostatic effect could not be highlighted.

The objectives of this study were to explore the effect of LOPs from LA on digestive bacteria using rumen content culture. We aimed 1) to compare the long-term effects of the major LOPs from LA on the ruminal bacterial community and 2) to check the ruminal bacterial response to oxidative stress by assaying SOD activity.

Methods

Long-term batch cultures

One HPOD resulting from LA oxidation, 13OOH cis-9,trans-11-C18:2 (13HPOD), and the two aldehydes produced from LA oxidation, hexanal (HEX) (purity ≥ 97%, Sigma Co., St Louis, MO, USA) and trans-2,trans-4-decadienal (T2T4D) (purity ≥ 85%, Sigma Co., St Louis, MO, USA), were selected for this experiment. 13HPOD was synthesized in the laboratory from pure LA by adapting the methods of Fauconnier et al. [15,16] and Lopez-Nicolas et al. [17], as described in Kaleem et al. [6]. Before the experiment, the 13-HPOD in this preparation was quantified as described later to a purity of 78%.

These LOPs are representative of LA oxidation: 13HPOD is the most abundant HPOD from LA oxidation in heated and/or stored oil and high-LA seeds [18,19] and an excellent marker of lipid peroxidation [20]; HEX and T2T4D are the most abundant saturated short-chain and unsaturated long-chain aldehydes generated during LA oxidation in oil and seeds [18,19].

Incubations were conducted in Erlenmeyer flasks with a fermentative substrate (1 g of 2 mm-ground meadow hay, 0.2 g of 1 mm-ground soybean meal and 0.25 g of 1 mm-ground corn grain) and no oxidation product (controls), 30 mg of 13-HPOD, 10 mg of HEX or 10 mg of T2T4D (extrapolated from Kaleem et al. [6]). Ruminal fluid was collected from a lactating cow before the morning meal. The cow was fed with a corn silage-based diet (36 kg of corn silage, 4 kg of soybean meal, 2 kg of hay, 1.5 kg of ground corn, 1.5 kg of ground wheat, 3 kg of concentrates, 0.2 kg of a mineral and vitamin supplement, and 30 g of salt). The rumen fluid was strained through a metal sieve (1.6 mm mesh). Carbon dioxide was blown in the container of rumen fluid to ensure complete oxygen removal. Later, it was transported to the laboratory under anaerobic and in the dark conditions, maintaining its temperature at 39°C. In the laboratory, 40 ml of rumen and 40 ml of bicarbonate buffer with minerals for bacterial growth (pH = 7; Na2HPO4.12H2O 19.5 g/l and NaHCO3 9.24 g/l: NaCl 0.705 g/l; KCl 0.675 g/l; CaCl2.2H2O 0.108 g/l and MgSO4.7H2O 0.180 g/l, gazed with CO2 and heated at 39°C) were added to the flasks, and the pH was measured (pH meter 3210, WTW, Weilheim, Germany). The flasks were then placed in a water bath rotary shaker (Aquatron; Infors AG, 4103 Bottmingen, Germany) at 39°C, filled with CO2, and closed with a rubber lid cap with an inserted plastic tube leading into the water to vent fermentation gas without oxygen entrance. Flasks were stirred at 130 rpm and not exposed to light during incubation. Every 24 h of incubation, the same quantities of LOP and fermentative substrate as at day 1 were added to each flask along with 20 mL of bicarbonate buffer, flaks were filled with CO2 before being closed again. Incubations were stopped 54 h or 102 h after the beginning of the incubations. To investigate ruminal biohydrogenation (data not shown), 60 mg of pure LA was added. Culture controls were prepared and incubated without oxidation products or LA. Three series of incubations were necessary to obtain 6 replicates per treatment and incubation duration. Each series of in vitro incubation was done with fresh rumen fluid.

Once the incubation was completed, the flasks were removed from the water bath and immediately placed in crushed ice. The pH was measured, and 1 mL of each culture was placed in an Eppendorf tube for bacterial community analysis and stored at -80°C until analysis. The rest of the flask was immediately stored at -18°C. The samples were freeze-dried (VirTis Freezemobile 25; Virtis, Gardiner, NY) and weighed. Flask contents were ground and homogenized in a ball mill (Dangoumau, Prolabo, Nogent-sur-Marne, France) and kept at -18°C for later analysis of SOD activity. Bacterial abundance was assessed by total qPCR.

Microbiological analyses

Total DNA from 1 ml of freeze-dried ruminal samples was extracted and purified using the QIAamps DNA Stool Mini kit (Qiagen Ltd, West Sussex, UK) according to the manufacturer’s documentation after a bead-beating step in a FastPrep Instrument (MP Biomedicals, Illkirch, France). The V3-V4 regions of 16S rRNA genes of samples were amplified from purified genomic DNA with the primers forward F343 and reverse R784, and PCR was carried out as described in Zened et al. [21]. As Illumina MiSeq technology enables paired-end 250-bp reads, we obtained overlapped reads that generated extremely high-quality, full-length reads of the entire V3 and V4 regions in a single run. Single multiplexing was performed using a 6 bp index, which was added to R784 during a second PCR with 12 cycles using forward (AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTCTTTCCCTACACGAC) and reverse primers (CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGATGTGACTGGAGTTCAGACGTGT). The resulting PCR products were purified and loaded onto an Illumina MiSeq cartridge (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) at the Genomic and Transcriptomic Platform (INRAE, Toulouse, France) according to the manufacturers’ instructions. The raw reads were treated with the FROGS pipeline [22] by following the FROGS’ operational procedure: (i) read demultiplexing, i.e., each pair-end read was assigned to its sample with the help of the previously integrated index. (ii) read preprocessing, i.e., removing sequences that did not match the proximal PCR primer sequences, removing sequences not between minimum and maximum sequencing length (less than 397 nucleotides and higher than 432) and removing sequences with at least one ambiguous base, (iii) chimaera removal, (iv) sequence clustering in clusters (operational taxonomic units) with denoising=yes and d=3, (v) cluster filtering, i.e., clusters with abundances above 0.005% of total sequences and present in at least 6 samples were retained, and (vi) cluster affiliation using the SILVA database (version 128) [23]. Once cluster affiliated we called it ASV.

The total number of bacteria in the cultures was estimated by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR), as described in Combes et al. [24]. Assays were performed using the ABI Prism 7900HT sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA) in optical grade 384-well plates in a final volume of 10 µl. The SYBR Green assay reaction mixture contained template DNA, a specific primer set at 100 nM (forward: ACTCCTACGGGAGGCAGCAG; reverse: ATTACCGCGGCTGCTGG) and 1X Power SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems, Carlsbad, CA, USA). A dissociation curve was added to SYBR Green assays to check the specificity of the amplification. Then, the results were compared with a standard curve to obtain the number of target copies in the sample. Standard DNA curves were generated by amplification of serial 10-fold dilutions of a reference plasmid containing the target 16S rRNA gene (accession no. EF445235 Prevotella bryantii).

Superoxide dismutase activity

The SOD activity was measured in ruminal cultures. Total SOD activity was evaluated by measuring the inhibition of pyrogallol activity, as described by Gladine et al. [25].

Calculations and statistical analysis

The bacterial diversity was estimated by Shannon and Simpson indexes with the R package phyloseq [26]. The relative abundances of phyla, families and genera were obtained by the sum of the sequences of all the ASVs belonging to the taxon, divided by the sum of the total sequences in the sample, from the count table obtained from the bioinformatics analysis. The graphs and tables show the mean values with the standard errors of the means calculated from these relative abundances. However, as these data are compositional, they require transformation before statistical analysis can be carried out. This transformation was carried out as recommended by Guillermo et al. [27], using the sequence count table. Data transformation and statistical analysis were performed with R software [28].

For the transformation of data, the zeros from the sequence count table were imputed using the Geometric Bayesian-multiplicative (GBM) method, before applying a Centred Log Ratio (CLR) transformation to our data.

First, a multivariate analysis of the bacterial community was completed using the package mixOmics [29]. To remove noisy and uninformative ASVs, a Sparse Partial Least Squares Discriminant Analysis (sPLS-DA) was performed to select a small number of ASVs (20 ASVs per component) relevant to discriminate each treatment (i.e., control, 13HPOD, HEX and T2T4D).

The CLR transformed data of major families and genera of bacteria (relative abundance > 0.01), the bacterial abundance and diversity indexes, and the SOD activity were compared using the general linear model (“stats” package). The model was:

Variable = mean + “series” effect + “treatment” effect + “incubation duration” effect + interaction “treatment ´ incubation duration” + residual error.

Then, a type-III ANOVA (“car” package) was conducted to obtain p-values. When a difference between treatments was significant (p<0.05), a pairwise comparison was performed using a Tukey test (“stats” package). Significance was declared at p≤0.05.

The relationship between SOD activity and bacterial genera was investigated by a relevance network using sPLS with a 0.6 cut-off.

Results

This study aimed to evidence in vitro effects of one peroxide (13HPOD) and the two aldehydes (HEX and T2T4D) produced from LA oxidation, on gut microbiota. Ruminal content was used for this test and incubated for 54 or 102 hours.

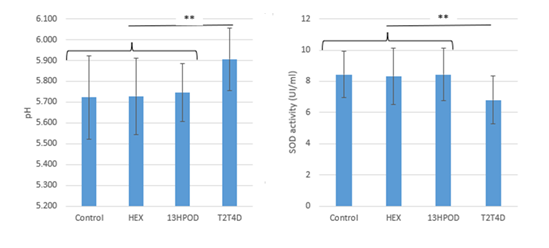

Concerning the pH of the ruminal cultures, the bacterial abundance and diversity, and SOD activity, there was no interaction between time of incubations and LA LOPs addition (supplemental table 1). Focusing on oxidative products effects, the addition of LA LOPs did not modify rumen bacterial abundances and diversity (Supplemental table 1), although impacting final pH and SOD activity. In both cases, it was T2T4D addition that induced a significant change: it led to a significant higher final pH and resulted in a lower SOD activity than the other treatments, which did not differ (Figure 1).

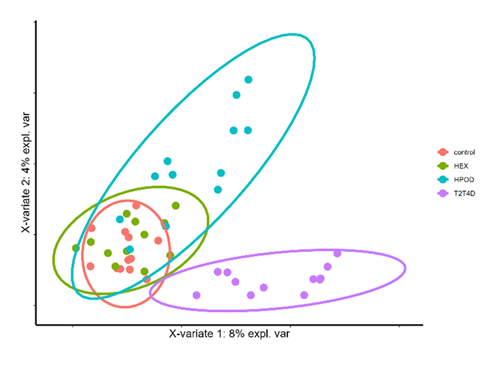

Figure 2 shows the sPLS-DA results obtained with treatments (control, HEX, 13HPOD or T2T4D) as discriminant factors. With AUC ROC > 0.94, the model allows good discrimination of our treatments. This figure shows 4 groups: 2 closed groups (HEX and HPOD) with an intersection, and the control and T2T4D group separated from the others, with a global balance error rate of 0.29. Using VIP function, the 20 high contributors presented a VIP > 4.5, (Table 1). The component 1 contributed the most to group discrimination (8% expl.var. vs. 4% and 3% respectively for component 2 and 3). It is the component discriminating the T2T4D treatment from the control and other treatments (Supplemental figure 1). The ASVs most often associated with control and HEX belonged to Bacteroidales S24-7 group family, with HPOD to Megasphaera genus and with T2T4D to Erysipelotrichaceae UCG-002 genus (Table 1).

Figure 1: Comparison of the effects of 13OOH cis-9,trans-11-C18:2 (13HPOD), hexanal (HEX), and trans-2,trans-4-decadienal (T2T4D) and a control incubated without oxidation products, on final pH and superoxide dismutase activity in ruminal cultures. Results are expressed as mean of 54 h plus 102 h values for each treatment, SD are represented by error-bars. **P ≤0.05.

|

ASVs affiliation reported as belonging to Phylum, Family, Genus |

Cluster number |

VIP2 |

Component |

value.var on the component |

Mean relative abundance3 |

|

Associated with control1 |

|||||

|

Spirochaetae, Spirochaetaceae, Treponema2 |

1219 |

13.2 |

3 |

-0.58 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales S24-7 group, unkown genus |

124 |

9.5 |

1 |

-0.4 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales BS11 gut group, unkown genus |

842 |

9 |

3 |

-0.4 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales BS11 gut group, unkown genus |

41 |

8.8 |

2 |

-0.39 |

0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales S24-7 group, unkown genus |

119 |

8.3 |

1 |

-0.35 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales S24-7 group, unkown genus |

73 |

7.3 |

1 |

-0.31 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales S24-7 group, unkown genus |

31 |

6.2 |

1 |

-0.26 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales S24-7 group, unkown genus |

24 |

5.4 |

1 |

-0.23 |

0.01 |

|

Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae, Lachnospiraceae NK3A20 group |

326 |

5 |

3 |

-0.22 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Prevotellaceae, Prevotella 1 |

998 |

5 |

3 |

-0.22 |

<0.01 |

|

Associated with HEX addition1 |

|||||

|

Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae, Lachnospiraceae ND3007 group |

1167 |

8 |

3 |

0.36 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales S24-7 group, unkown genus |

10 |

5.3 |

1 |

-0.23 |

0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidales S24-7 group, unkown genus |

5 |

5.1 |

1 |

-0.21 |

0.05 |

|

Associated with HPOD addition1 |

|||||

|

Firmicutes, Veillonellaceae, Megasphaera |

369 |

13.3 |

2 |

0.59 |

<0.01 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Prevotellaceae, Prevotellaceae YAB2003 group |

1382 |

12.8 |

2 |

0.56 |

<0.01 |

|

Spirochaetae, Spirochaetaceae, Treponema2 |

409 |

4.6 |

2 |

0.2 |

<0.01 |

|

Firmicutes, Veillonellaceae, Megasphaera |

1526 |

4.6 |

2 |

0.2 |

<0.01 |

|

Associated with T2T4D addition1 |

|||||

|

Firmicutes, Erysipelotrichaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae UCG-002 |

29 |

8.7 |

1 |

0.37 |

<0.01 |

|

Firmicutes, Erysipelotrichaceae, Erysipelotrichaceae UCG-002 |

4 |

5.7 |

1 |

0.24 |

0.01 |

|

Firmicutes, Acidaminococcaceae, Succiniclasticum |

854 |

5.2 |

1 |

0.22 |

<0.01 |

1 Control: incubated without oxidation products nor linoleic acid; HEX: hexanal; 13HPOD: 13-OOH cis-9,trans-11-C18:2; T2T4D: trans-2,trans-4 decadienal.

2 Variable importance in projection: relative importance in the prediction model by sPLS-DA.

3 Mean was calculated regardless of treatment as mean of cluster sequences/total sequences.

Table 1: ASVs associtaed with control or oxydative products addition in the sPLS-DA

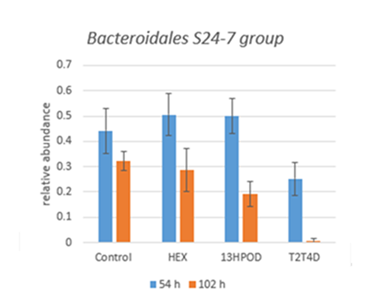

Figure 3: Effect of 13OOH cis-9,trans-11-C18:2, hexanal, and trans-2,trans-4-decadienal compared to control on Bacteroidales S24-7 group unkown genus abundance in ruminal cultures incubated 54 h or 102 h. The relative abundance of this genus was significantly (P < 0.01) affected by the interaction of incubation duration and oxidative product addition. T2T4D was the most effective oxidative product for both incubation duration, 13HPOD only induced a modification in 102 h incubations, HEX and control were not significantly different whatever the duration of incubation.

Figure 4: Bacterial clusters strongly linked with superoxide dismutase activity. Analysis was performed using sPLS and the network presents clusters with correlation values > |0.6|: red lines represent negative correlations, and green lines represent positive correlations. Affiliation of clusters on Silva database is in table 3.

At the family and genus level (Table 2), the addition of T2T4D had a strong impact compared to others, in particular it significantly increased Bifidobacterium genus (approximately ´ 5), Prevotella 7 genus (approximately ´ 3) and Lachnospiraceae family (approximately ´ 2), while it significantly decreased Bacteroidales S24-7 group unknown genus (approximately ´ 3) and Prevotella 1 genus (approximately ´ 2). Even, there were almost no bacteria from Bacteroidales S24-7 group unknown genus left after 102h incubation, because of an interaction between T2T4D addition and long incubation time (Table 2 and figure 3). Effects were much less important for other families and genera, excepted Erysipelotrichaceae family significantly increased by13HPOD and T2T4D.

|

Taxonomic level |

Control1 |

HEX1 |

13HPOD1 |

T2T4D1 |

SEM |

Ptreatment² |

Ptime² |

Inter² |

|

Actinobacteria Bifidobacteriaceae Bifidobacterium |

0.01b |

0.01b |

0.01b |

0.05a |

0.005 |

*** |

**** |

* |

|

Bacteroidetes Bacteroidales BS11 gut group unkown genus |

0.03a |

0.01a |

0.01b |

0.01b |

0.002 |

**** |

**** |

NS |

|

Bacteroidetes Bacteroidales S24-7 group unkown genus |

0.38a |

0.40a |

0.35a |

0.13b |

0.018 |

**** |

** |

*** |

|

Bacteroidetes Prevotellaceae Prevotella 1 |

0.07a |

0.05a |

0.07a |

0.03b |

0.006 |

*** |

*** |

* |

|

Bacteroidetes Prevotellaceae Prevotella 7 |

0.02b |

0.05b |

0.04b |

0.14a |

0.012 |

** |

**** |

NS |

|

Bacteroidetes Rikenellaceae Rikenellaceae RC9 gut group |

0.03a |

0.02a |

0.01b |

0.03a |

0.004 |

**** |

** |

* |

|

Firmicutes Christensenellaceae Christensenellaceae R-7 group |

0.07a |

0.08a |

0.06b |

0.07b |

0.004 |

**** |

**** |

** |

|

Firmicutes Lachnospiraceae

|

0.09c |

0.10b,c |

0.13b |

0.19a |

0.006 |

**** |

NS |

NS |

|

Firmicutes Erysipelotrichaceae

|

0.03b |

0.03b |

0.09a |

0.09a |

0.009 |

**** |

NS |

NS |

1Control: incubated without oxidation products nor linoleic acid; HEX: hexanal; 13HPOD: 13-OOH cis-9,trans-11-C18:2; T2T4D: trans-2,trans-4 decadienal.

2Ptreatment: effect of oxidation products; Ptime: effect of time of incubation; Inter: interaction between effect of oxidation products and time of incubation; NS: non-significant (P>0.10); * 0.10>P>0.05; **P ≤0.05; *** P ≤0.01; **** P ≤0.001.

abValues with different superscript in a same raw, significantly differ (P<0.05).

Table 2: Families and genera (relative abundance > 0.01) affected by the addition of oxidative products.

We chose to use the SOD assay to explore possible antioxidant responses of bacteria to our LA LOPs. A potential link between some genera or families and SOD activity in the rumen is presented in (Table 3 and Figure 4). Among ASVs genus highly and positively linked with SOD activity (coefficient of sPLS network > 0.6), we found Succinivibrio genus. Other ASVs belonged to Prevotellaceae and Lachnospiraceae family.

|

ASVs affiliation reported as belonging to Phylum, Family, Genus |

Cluster number |

r1 |

|

Proteobacteria, Succinivibrionaceae , Succinivibrio |

Cluster_77 |

0.71 |

|

Proteobacteria, Succinivibrionaceae , Succinivibrio |

Cluster_120 |

0.69 |

|

Proteobacteria, Succinivibrionaceae , Succinivibrio |

Cluster_192 |

0.64 |

|

Proteobacteria, Succinivibrionaceae , Succinivibrio |

Cluster_210 |

0.69 |

|

Proteobacteria, Succinivibrionaceae , Succinivibrio |

Cluster_402 |

0.66 |

|

Proteobacteria, Succinivibrionaceae , Succinivibrio |

Cluster_664 |

0.61 |

|

Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae, [Eubacterium] cellulosolvens group |

Cluster_308 |

0.66 |

|

Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae, Lachnospiraceae UCG-008 |

Cluster_1844 |

0.62 |

|

Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae, Roseburia |

Cluster_135 |

0.66 |

|

Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae, Roseburia |

Cluster_807 |

0.6 |

|

Firmicutes, Lachnospiraceae, Pseudobutyrivibrio |

Cluster_345 |

0.66 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Prevotellaceae, Prevotella 1 |

Cluster_136 |

0.62 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Prevotellaceae, Prevotella 7 |

Cluster_462 |

0.61 |

|

Bacteroidetes, Prevotellaceae, Prevotellaceae YAB2003 group |

Cluster_207 |

0.67 |

|

Firmicutes, Ruminococcaceae, Ruminococcaceae UCG-014 |

Cluster_53 |

0.66 |

|

Firmicutes, Ruminococcaceae, Ruminococcaceae NK4A214 group |

Cluster_58 |

-0.61 |

|

Firmicutes, Ruminococcaceae, Ruminococcus 1 |

Cluster_830 |

-0.62 |

|

Firmicutes, Ruminococcaceae, Saccharofermentans |

Cluster_208 |

-0.64 |

1r = Pearson coefficient

Table 3: ASVs strongly (r > 0 .6) corralated with superoxide dismutase activity.

Discussion

Effect of lipid oxidation products on the ruminal bacterial community

Heating high-LA fats increases their HEX, T2T4D and 13HPOD contents [6,18], whose effects were investigated separately in the present study through the addition of 13HPOD, HEX and T2T4D into cultures with a rumen microbiota. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the effects of LA LOPs on the rumen microbiota and its SOD activity.

Bacterial abundance and diversity were not affected by the tested LA LOPs, as reported in a previous study using 5h short-term incubations [6].

If diversity indexes are difficult to compare with other studies, the total bacterial abundances (9.7 log copies of DNA/ml, 11 log copies of DNA/mg, or 2.4´1011 copies of DNA per g of DM of cultures, on overall average) obtained in our study were similar to those reported by Henderson et al. [30] for cows and sheep, and Singh et al. [31] for buffaloes, underlining the relevance of the system.

Except for T2T4D, the LOPs had no effect on the final pH, which was similar to that of the control (Figure 1). Bacterial populations were highly affected by LOPs addition (Figure 2), in particular some genera were highly affected by T2T4D (Table 2). The addition of T2T4D highly decreased relative abundances of Bacteroidales S24-7 group unknown genus of Bacteroidetes phylum and increased some Firmicutes populations, leading to an inversion of the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio. This one was respectively 1.8, 1.6, 1.2 and 0.7 for control, HEX, HPOD and T2T4D cultures. That’s why on the first component of sPLS-DA (the most discriminant one), control and HEX were mainly associated with ASVs belonged to Bacteroidales S24-7 group unknown genera, when only Firmicutes were associated with T2T4D. Some ASVs were specially associated with HOPD. Those links suggested that some bacteria could resist HPOD and T2T4D addition, when others were affected by their addition.

Kubo et al. [11] reported an antimicrobial effect of long-chain and unsaturated aldehydes on some bacteria in monoculture but did not test their effect on bacteria belonging to the Bacteroidetes phylum, nor others identified by our sPLS. They also showed that HEX had no effect on the growth of their selected bacteria in monocultures. Huws et al. [5] showed an effect of hydroperoxyoctadecatrienoic acid (HPOD obtained from oxidation of a-linolenic acid of grass) on the ruminal microbiota. They found that this HPOD has potential antimicrobial activity, particularly on Prevotellaceae, Lachnospiraceae and Ruminococcaceae, which was not the case in our study with an LA HPOD. On the other hand, Fanta et al. [32] reported a bacteriostatic effect of peroxides.

The greatest effect of LA LOPs was mainly due to T2T4D and consisted to a decrease in the Bacteroidales S24-7 group leading to a great diminution of the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio. In ruminants, a decrease in the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio is generally associated with subacute ruminal acidosis, which is associated with systemic inflammation when a cow’s diet is rich in grain. Some metabolites produced by ruminal bacteria, such as lipopolysaccharides, could be associated with the inflammatory response, at least in part [33]. However, the relationship between the ruminal microbiome and health is still unclear in ruminants. In humans, Krych et al. [34] suggested that a decrease in the Bacteroidetes/Firmicutes ratio could promote diabetes, and Castaner et al. [35] reported a link between the diminution of this ratio and obesity. Besides, the Bacteroidales S24-7 group could act in favour of diabetes protection in mice [34] and of diarrhoea protection during weaning in pigs [36]. Nevertheless, all these studies suggest a potential negative effect of T2T4D on the health of animals and humans through a great modification of their gut microbiota, with the view that many strains are shared between the human intestinal and ruminal microbiomes [15].

Response of bacteria to oxidative stress

To investigate the rumen bacterial response to LA LPO addition, we chose to measure SOD activity.

In the incubations with T2T4D, SOD activities were significant, when it was not affected by others LA LOPs. Nevertheless, there are many antioxidant systems in the rumen [37], so the lack of effect on the SOD activity does not mean that the antioxidant response was not affected when oxidation products were added to the media.

Fulghum and Worthington [13] studied the SOD capacity of some ruminal bacteria. Among them Succinivibrio dextrinosolvens had great SOD activity, which fitted with our results. Other genera from Prevotellaceae and Lachnospiraceae were also reported to develop a SOD activity in this study but depending on species (e.g. Ruminoccocus) or subspecies (e.g. Prevotella ruminicola formerly Bacteroides ruminicola). As mentioned above, there are other forms of bacterial fight against oxidative stress [37], and our measurement is only a first, non-exhaustive approach. Nevertheless, it is highly likely that some bacteria were probably able to resist LOPs, like Lachnospiraceae (Table 1), better than some other bacteria, particularly those belonging to the Bacteroidales S24-7 group. Further studies are necessary to understand how the digestive microbiota, as a whole and at the level of each bacteria, resist the oxidative stress generated in its ecosystem.

Conclusion

This study contributes to providing knowledge on the effect of LA LOPs on the digestive microbiota and its SOD activity.

Long-term batch cultures demonstrated the effects of some oxidation-products on bacterial communities. Mainly, the ruminal bacterial community was highly affected by T2T4D, leading to a diminution of fermentation that resulted in a higher final pH in these cultures than in others, and a lower SOD activity. Modification of bacterial community represents a potential health risk for the host, but in vivo studies are needed to draw conclusions.

Data availability

Metabarcoding data was deposited in publicly accessible databases. Sequence data are accessible through SRA of NCBI (PRJNA733108).

Author contributions

Annabelle Meynadier conceived the experiment, carried out the analysis of the data and their interpretation, and wrote the manuscript. Géraldine Pascal performed bioinformatics. Laurent Cauquil and Tiphaine Blanchard performed biostatistics and the formatting of figures. Yves Farizon and Muhammad Kaleem conducted the trial. Sylvie Combes performed the microbiota quantification and Denys Durant the SOD activity. Francis Enjalbert and Djamila Ali Haimoud-Lekhal participated to the interpretation of the results and the redaction of the manuscript. All authors read, improved and approved the final manuscript.

Additional information

The authors have no competing financial interests

References

- Frankel EN. Lipid Oxidation, 2nd Edition (2005).

- Vangaveti V, Baune BT, Kennedy RL. Review: Hydroxyoctadecadienoic acids: novel regulators of macrophage differentiation and atherogenesis. Ther Adv Endocrinol Metab 1 (2010): 51-60.

- Durand D, Damon M, Gobert M. Le stress oxydant chez les animaux de rente: principes généraux. Cah Nutr Diététique 48 (2013): 218-224.

- Miller JK, Brzezinska-Slebodzinska E, Madsen FC. Oxidative stress, antioxidants, and animal function. J Dairy Sci 76 (1993): 2812-2823.

- Huws SA, Scott MB, Tweed JKS, et al. Fatty acid oxidation products (‘green odour’) released from perennial ryegrass following biotic and abiotic stress, potentially have antimicrobial properties against the rumen microbiota resulting in decreased biohydrogenation. J Appl Microbiol 115 (2013): 1081-1090.

- Kaleem A, Enjalbert F, Farizon Y, Troegeler-Meynadier A. Effect of chemical form, heating, and oxidation products of linoleic acid on rumen bacterial population and activities of biohydrogenating enzymes. J Dairy Sci 96 (2013): 7167-7180.

- Privé F, Combes S, Cauquil L, et al. Temperature and duration of heating of sunflower oil affect ruminal biohydrogenation of linoleic acid in vitro. J Dairy Sci 93 (2010): 711-722.

- Goodarzi BF, Vahjen W, Mader A, et al. The effects of different thermal treatments and organic acid levels in feed on microbial composition and activity in gastrointestinal tract of broilers. Poult Sci 93 (2014): 1440-1452.

- Wu Z, Guo Y, Zhang J, et al. High-Dose Vitamin E Supplementation Can Alleviate the Negative Effect of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis in Dairy Cows. Animals 13 (2023): 486.

- Brioukhanov AL, Netrusov AI. Catalase and superoxide dismutase: Distribution, properties, and physiological role in cells of strict anaerobes. Biochem Biokhimiia 69 (2004): 949-962.

- Kubo A, Lunde CS, Kubo I. Antimicrobial Activity of the Olive Oil Flavor Compounds. J Agric Food Chem 43 (1995): 1629-1633.

- Deng W, Hamilton KTR, Nielsen MT, et al. Effects of six-carbon aldehydes and alcohols on bacterial proliferation. J Agric Food Chem 41 (1993): 506-510.

- Fulghum RS, Worthington JM. Superoxide dismutase in ruminal bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 48 (1984): 675-677.

- Lenártová V, Holovská K, Javorský P. The influence of mercury on the antioxidant enzyme activity of rumen bacteria Streptococcus bovis and Selenomonas ruminantium. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 27 (1998): 319-325.

- Seshadri R, Leahy SC, Attwood GT, et al. Cultivation and sequencing of rumen microbiome members from the Hungate1000 Collection. Nat Biotechnol 36 (2018): 359-367.

- Fauconnier ML, Perez AG, Sanz C, et al. Purification and Characterization of Tomato Leaf (Lycopersicon esculentum Mill.) Hydroperoxide Lyase. J Agric Food Chem 45 (1997): 4232-4236.

- López-Nicolás JM, Pérez-Gilabert M, Garc??a-Carmona F. Rapid reversed-phase high-performance liquid chromatographic determination of the regiospecificity of lipoxygenase products on linoleic acid. J Chromatogr A 859 (1999): 107-111.

- Kaleem M, Farizon Y, Enjalbert F, et al. Lipid oxidation products of heated soybeans as a possible cause of protection from ruminal biohydrogenation. Eur J Lipid Sci Technol 115 (2013): 161-169.

- Kaleem M, Enjalbert F, Farizon Y, Meynadier A. Feeding heat-oxidized oil to dairy cows affects milk fat nutritional quality. Animal 12 (2018): 183-188.

- Spiteller P, Spiteller G. 9-Hydroxy-10,12-octadecadienoic acid (9-HODE) and 13-hydroxy-9,11-octadecadienoic acid (13-HODE): excellent markers for lipid peroxidation. Chem Phys Lipids 89 (1997): 131-139.

- Zened A, Combes S, Cauquil L, et al. Microbial ecology of the rumen evaluated by 454 GS FLX pyrosequencing is affected by starch and oil supplementation of diets. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 83 (2013): 504-514.

- Escudié F, Auer L, Bernard M, et al. FROGS: Find, Rapidly, OTUs with Galaxy Solution. Bioinformatics 34 (2018): 1287-1294.

- Quast C, Pruesse E, Yilmaz P, et al. The SILVA ribosomal RNA gene database project: improved data processing and web-based tools. Nucleic Acids Res 41 (2013): D590-D596.

- Combes S, Michelland RJ, Monteils V, et al. Postnatal development of the rabbit caecal microbiota composition and activity. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 77 (2011): 680-689.

- Gladine C, Morand C, Rock E, et al. The antioxidative effect of plant extracts rich in polyphenols differs between liver and muscle tissues in rats fed n-3 PUFA rich diets. Anim Feed Sci Technol 139 (2007): 257-72.

- McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. Plos one 8 (2013): e61217.

- Martinez BG, Meynadier A, Daunis EP, et al. Compositional analysis of ruminal bacteria from ewes selected for somatic cell score and milk persistency. Plos one 16 (2021): e0254874.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria (2023).

- Rohart F, Gautier B, Singh A, et al. MixOmics: An R package for ’omics feature selection and multiple data integration. PLoS Comput Biol 13 (2017): e1005752.

- Henderson G, Cox F, Kittelmann S, et al. Effect of DNA Extraction Methods and Sampling Techniques on the Apparent Structure of Cow and Sheep Rumen Microbial Communities. Plos One 8 (2013): e74787.

- Singh KM, Pandya PR, Tripathi AK, et al. Study of rumen metagenome community using qPCR under different diets. Meta Gene 2 (2014): 191-199.

- Fanta D, Bardach H, Poitscheck Ch. Investigations on the bacteriostatic effect of benzoyl peroxide. Arch Dermatol Res 264 (1979): 369-371.

- Khafipour E, Li S, Plaizier JC, et al. Rumen Microbiome Composition Determined Using Two Nutritional Models of Subacute Ruminal Acidosis. Appl Environ Microbiol 75 (2009): 7115-7124.

- Krych ?, Nielsen DS, Hansen AK, et al. Gut microbial markers are associated with diabetes onset, regulatory imbalance, and IFN-γ level in NOD Mice. Gut Microbes 6 (2015): 101-109.

- Castaner O, Goday A, Park YM, et al. The Gut Microbiome Profile in Obesity: A Systematic Review. Int J Endocrinol 8 (2018): 1-9.

- Sun J, Du L, Li X, Zhong H, Ding Y, Liu Z, et al. Identification of the core bacteria in rectums of diarrheic and non-diarrheic piglets. Sci Rep 9 (2019): 1-10.

- Gazi MR, Yokota M, Tanaka Y, et al. Effects of protozoa on the antioxidant activity in the ruminal fluid and blood plasma of cattle. Anim Sci J 78 (2007): 34-40.

Impact Factor: * 3.8

Impact Factor: * 3.8 Acceptance Rate: 77.96%

Acceptance Rate: 77.96%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks