Myosteatosis in Oesophagogastric Cancer: A Systematic Review

Yannick Deswysen1,2*, Marc Van den Eynde3,4, Nicolas Lanthier2,4

¹UpperGI surgical unit, Service de chirurgie et transplantation abdominale, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Institut Roi Albert II, UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium

2Laboratoire de gastroentérologie et d’hépatologie, Institut de Recherche Expérimentale et Clinique, Université catholique de Louvain, Brussels, Belgium

3Service d’Oncologie Médicale, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Institut Roi Albert II, UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium

4Service d’Hépato-gastroentérologie, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, UCLouvain, Brussels, Belgium

*Corresponding Author: Yannick DESWYSEN, MD, Service de Chirurgie et Transplantation Abdominale,

Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc, Université Catholique de Louvain 10, Avenue Hippocrate, B-1200 Bruxelles, Belgium.

Received: 09 July 2025; Accepted: 16 July 2025; Published: 15 August 2025

Article Information

Citation:

Yannick Deswysen, Marc Van den Eynde, Nicolas Lanthier. Myosteatosis in Oesophagogastric Cancer: A Systematic Review. Journal of Cancer Science and Clinical Therapeutics. 9 (2025): 112-131.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Objectives and Methods: Myosteatosis, a pathological fat infiltration in muscle, is gaining attention in oncology, especially in oesophagogastric cancer. This systematic review aimed to summarise current evidence on its association with oncological outcomes, alongside sarcopenia, inflammation, and treatment effects. Four databases were searched up to October 2024.

Results: Of 132 articles screened, 34 were included (9814 patients). Sarcopenia and myosteatosis prevalence ranged from 15–70% and 11–84%. Both were frequently linked to increased mortality and higher complication rates following cancer treatment. Several simple inflammatory scores were also correlated with altered body composition and poor prognosis.

Conclusions: Sarcopenia and myosteatosis appear to be negative prognostic factors in oesophagogastric cancer. Their association with inflammatory markers is also suggested. However, variability in definitions, particularly for myosteatosis, limits comparability across studies, highlighting the need for standardised diagnostic criteria to better assess their impact and underlying mechanisms.

Keywords

<p>Oesophagogastric cancer; Sarcopenia; Myosteatosis; Muscle function; Oncological outcomes; Immune-inflammatory markers</p>

Article Details

Introduction

Oesophageal and gastric cancer are associated with significant morbidity and mortality rates worldwide [1]. Despite advancements in surgical, medical, and therapeutic treatments, patient survival often remains limited, underscoring the urgent need to identify new prognostic factors and therapeutic targets [2]. Body composition, encompassing muscle mass, adipose tissue level, and inflammatory and nutritional parameters, plays a pivotal role in treatment response and survival outcomes among cancer patients. Variations in body composition primarily involve two main entities: sarcopenia and myosteatosis. Sarcopenia is defined by the loss of skeletal muscle mass and function [3], while myosteatosis is defined by an excessive accumulation of lipid within skeletal muscle tissue [4]. Sarcopenia, which is well-documented, is associated with poor clinical outcomes, including an increased risk of infection, loss of function, increased chemotherapy related toxicity and mortality [5-7].

Myosteatosis, reflective of deteriorating muscle composition, is increasingly acknowledged as a potential prognostic marker in the context of oesophagogastric cancer [8]. In various malignancies, such as hepatocellular, colorectal or bladder cancers, myosteatosis has been linked to reduced muscle quality, impaired metabolic function, and poorer clinical outcomes. These outcomes include higher rates of complications, reduced tolerance to treatments, and lower overall survival [9-11]. However, the precise impact on clinical outcomes, particularly in relation to inflammatory and nutritional parameters, as well as the physical functional status of patients, remains incompletely understood and subject to ongoing debate. Fat accumulation within muscles occurs predominantly in two areas: within muscle fibres (intramyocellular lipids) and in the interstitial spaces (intermuscular fat) [12]. This accumulation is particularly detrimental to locomotor and respiratory muscles, exacerbating functional decline and reducing patient autonomy [13]. Such effects may partly explain the association of myosteatosis with increased treatment morbidity and mortality.

In the context of cancer, myosteatosis may be driven by mechanisms distinct from those in metabolic diseases, such as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) or type 2 diabetes [14]. In cancer, tumour-induced systemic inflammation, mediated by cytokines such as interleukin-6 (IL-6) and tumour necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), contributes to muscle breakdown and lipid dysregulation [15]. Alterations in proteins such as perilipins, which regulate lipid storage, further exacerbated abnormal fat deposition in muscles [16]. Understanding the mechanics is essential to identifying actionable causes to improve patient care. A critical question of causality arises: does the tumour directly induce myosteatosis, or does pre-existing muscle fat accumulation create a pro-inflammatory environment that promotes tumour aggressiveness? Regardless of direction, the interaction appears to amplify both tumour progression and muscle degradation.

Myosteatosis profoundly impairs muscle function, reducing contractility, strength, and endurance. Additionally, the accumulation of intramuscular lipids promotes the release of free fatty acids, which, through oxidative processes, generate oxidative stress. This oxidative stress induces cellular damage and exacerbates local inflammation, further accelerating muscle degradation. These mechanisms can contribute to increased muscle stiffness and diminished mobility, particularly in the elderly [17]. Oxidative stress and inflammation are indeed recognised as key pathological features of ageing skeletal muscle, contributing to the progressive loss of muscle mass and function [18]. Addressing myosteatosis in oesophagogastric cancer could improve patient outcomes by targeting both the tumour and the associated muscle dysfunction. This approach may pave the way for integrated therapies aimed at enhancing metabolic and functional recovery.

This systematic review aims to synthesize the current evidence regarding the multifaceted role of myosteatosis, alongside inflammatory and nutritional parameters, and the physical functional status in oesophagogastric cancer. We will explore the current implications of myosteatosis on survival, postoperative complications, and systemic immuno-inflammatory response.

Methods

Search strategy

A systematic literature research was conducted independently by two investigators based on the PubMed/Medline, Embase, Scopus, and Cochrane databases until 31 October, 2024. The search keywords (« myosteatosis » OR « muscle fat infiltration » AND « oesophageal cancer ») and (« myosteatosis » OR « muscle fat infiltration » AND « gastric cancer »). Additionally, the citation lists of review articles were manually analysed for potentially eligible studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria were studies published in English exploring the impact of myosteatosis in gastric and/or esophageal cancer in adult’s patients. Exclusion criteria were: 1) non-human study, 2) duplicative studies, 3) letter, review, case reports, conference abstracts, 4) unusable data.

Study selection

Two authors independently selected studies on title and abstract. Studies that met inclusion data have been included to analyse the full-text. The 2 investigators analysed the full-texts, and a third reviewer resolved any disagreements.

Data extraction

Data extracted from selected articles included study characteristics (authors, journal, country, study design, sample size, type of cancer, cancer stage, type of treatment performed, follow-up), patient demographics (gender, age), body composition measurements (body component analysis method, index, cutoff, anatomical location of analysis, software used), functional physical evaluation, prognostic value (overall survival, recurrence free survival, disease free survival, progression free survival), treatment complications and immuno-inflammatory response (C-reactive protein (CRP), neutrophils, lymphocytes, platelets, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR), platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR)).

Results

1) Data collection

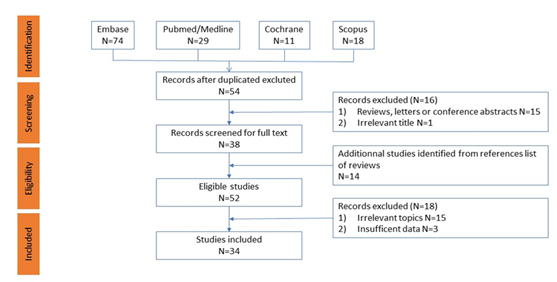

Of the 132 manuscripts evaluated, 34 articles met the inclusion criteria totalling 9,814 patients [8, 19-51] (Figure 1). Depending on the trials, sample sizes ranged between 45 and 1,147 patients. Among these, 22 studies included patients with gastric cancer [28-45, 49-51], 7 with oesophageal cancer [19, 21-24, 46, 48] and 6 with both [8, 20, 25-27, 47].

All studies, including the type of cancer, treatment modalities, methods for assessing sarcopenia and myosteatosis, cut-off values for their diagnosis, and main findings are listed in Table 1. Most studies used computed tomography (CT) images at the third lumbar level (L3). One study employed a combination of CT and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) [38], while two analysed images at the L4 level [22, 31]. Six studies evaluated the psoas major and paraspinal muscles in the abdominal region [19, 22, 26, 39, 41, 43], but the majority measured the total abdominal muscle area (TAMA) without specifying which muscles were assessed [8, 20, 21, 23-25, 27-38, 40, 42, 44-51].

Figure 1: Flow chart

2) Myosteatosis prevalence in oesophagogastric cancer

In terms of muscle quality, different terminologies were used by authors, such as mean attenuation, Hounsfield units, skeletal muscle (SM) attenuation, intramuscular adipose concentration, or skeletal muscle radiation attenuation. For consistency, we standardised the terminology as “skeletal muscle density” (SMD).

The variability in cut-off values used to define sarcopenia and myosteatosis presents a challenge for data comparison. A significant portion of studies [20, 23, 25, 27, 29, 35, 36, 42] relied on the data from Martin et al [52], while others established cut-offs specific to their populations through statistical analyses [19, 30, 32, 39, 43-45, 49-51]. For reference, Martin's criteria for defining sarcopenia are based on gender and BMI without measuring muscle strength, which is usually recommended when diagnosing sarcopenia, and solely on BMI for measuring myosteatosis. Thus, sarcopenia is defined as a SMI <43 cm2/m2 in men with a BMI <25 kg/m2, <53 cm2/m2 in men with a BMI ≥25 kg/m2, and <41 cm2/m2 in women. Low MA was defined as a mean attenuation <41 HU in patients with a BMI <25 kg/m2 and <33 HU in those with a BMI ≥25 kg/m2 (Table 1.) [52]. Some studies categorised patients using tertiles, whereas others utilised continuous data for group definitions. Based on the criteria set by the researchers, the prevalence rate for sarcopenia ranged from 15.4 to 69.9% while the prevalence of myosteatosis ranged from 11.0 to 84.0%. When data are available, the percentage of women presenting sarcopenia and/or myosteatosis is higher than that of men [20, 25].

Table 1: Incidence of myosteatosis and sarcopenia.

CSA = cross sectional area (cm²) ; CT = chemotherapy ; RCT = radiochemotherapy ; IMAC = intramuscular adipose concentration (HU) ; HUAC = Hounsfield unit average calculation (HU); IT = immunotherapy ; PMA = psoas muscle attenuation (HU) ; PMI = psoas muscle mass index (cm²/m²); SMD = skeletal muscle density (HU) ; SMI = skeletal muscle mass index (cm²/m²); SM-RA = skeletal muscle radiation attenuation (HU) ; TAMA = total abdominal muscle area ; TPA = total psoas area (mm² /m²) ; NDA = no data available ; None = using continuous variables.

3) Association between sarcopenia, myosteatosis and oncological outcomes

Twenty-nine studies reported the prognostic impact of sarcopenia and myosteatosis [8, 19, 21-32, 34, 36, 38-46, 48-51]. These findings are summarised in Table 2. The pooled analysis demonstrated that patients with myosteatosis faced a higher risk of mortality compared with those without myosteatosis. Low SMD was identified as an independent prognostic factors for overall survival (OS) [19, 22, 26, 29, 31, 32, 40-45, 48-51], disease free survival (DFS) [19, 29, 31, 45, 50], progression-free survival (PFS) [49, 51], and cancer-specific survival (CSS) [41, 44].

Table 2: Prognostic impact of myosteatosis and sarcopenia.

CSS= cancer-specific survival ; DFS : disease free-survival ; HUAC = Hounsfield unit average calculation ; IMAC : intramuscular adipose tissue content ; MA = muscle attenuation ; mIMAC = modified intramuscular adipose tissue content ; OS = overall survival ; PFS : progression-free survival ; PMI = psoas muscle index (cm²/m²) ; PMMA= mean attenuation within paraspinal muscle ; PMRA = paraspinal muscle radiation attenuation ; PNI = prognostic nutritional index = Albumin+5 x total lymphocyte count (x 109/L) ; SMD = skeletal muscle density ; SMI = skeletal muscle index ; SMRA = skeletal muscle radiation attenuation ; TPA = total psoas area

However, five studies reported no significant association between myosteatosis and OS [27, 30, 34, 36, 46]. Additionally, one study observed improved OS and PFS in patients with myosteatosis treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy, when the latter is not associated with systemic inflammation. The authors suggested that the positive impact of myosteatosis on OS could be attributed to factors such as the low prevalence of overweight or obese patients, a reduced proportion of visceral fat, and the predominance of squamous cell carcinoma—a histological type less commonly associated with obesity [23].

Findings for sarcopenia were also reported in the Table 2. Low skeletal muscle index (SMI) was identified as an independent prognostic factors for overall survival (OS) [19, 21, 24, 25, 28, 30, 32, 34, 39-41, 43, 44, 46, 48-51], disease free survival (DFS) [28, 32, 39, 40, 50] and progression-free survival (PFS) [38, 49, 51]. No significant association between sarcopenia and OS was find in eight studies [22, 26, 27, 29, 36, 38, 42, 45].

4) Association between myosteatosis and immuno-inflammatory markers

Among 34 articles included in this review, 8 examined the relationship between body composition and immune-inflammatory parameters - 7 in gastric cancer [28-30, 33, 36, 39, 44] and 1 in oesophageal cancer [23]. Various scores derived from simple markers, such as CRP, NLR, PLR, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR), prognostic nutritional index (PNI). In the only study concerned, there was no correlation between CRP and myosteatosis [33].

In gastric cancer, immunoinflammatory markers appear to influence tumour outcome by affecting progression or survival. For instance, a high NLR has been linked to poorer OS and recurrence-free survival (RFS), as has a high PLR [29, 30, 39] although this association was not observed in another study [36]. The combination of sarcopenia or myosteatosis with elevated NLR or PLR further exacerbates the negative impact on survival. High NLR may correlate with poorer physical condition, commonly seen in patients with muscle mass loss or myosteatosis. Sarcopenic patients often exhibit a more pronounced inflammatory response. Two studies found that a high LMR ratio negatively impacts survival [30, 39]. When combined with myosteatosis, the risk of progression doubled. A reduced lymphocyte count and increased monocyte count reflect an immunosuppressive and inflammatory environment, which may reflect a low LMR [39]. The PNI, a multiparametric marker combining nutritional and immune factors, was first introduced by Buzby et al. [53]. A low PNI ratio suggests a compromised nutritional status and/or immunosuppression and is associated with sarcopenia and myosteatosis and reduced OS in gastric cancer patients [28, 30].

Finally, as noted earlier, myosteatosis was significantly associated with favourable PFS and OS in one study of patients treated with definitive chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced esophageal cancer. Increased NLR was more frequently observed in patients without myosteatosis. In subgroups analyses, patients with myosteatosis and low NLR demonstrated a reduced risk of tumour progression and mortality, suggesting that myosteatosis in the absence of systemic inflammation predicts a favourable prognosis [23].

5) Association between myosteatosis and muscle function

Few studies have comprehensively analysed the correlations between body composition, muscle strength and physical performance in patients treated for oesophagogastric cancer. Most studies adopted the muscle mass as a single parameter for evaluating sarcopenia, overlooking the critical role of muscle strength and functional physical capacity. Five studies assessed muscle function by using the hand-grip-test (HGT) to measure muscle strength [35, 37, 40, 41, 47], and only one study evaluated preoperative physical performance status by using the six-minute walk test (6MWT) [40].

Waki et al reported an inverse correlation between myosteatosis, represented by intramuscular adipose tissue content (IMAC), and high HGT in both men (r=-0.373, p<0.001) and women (r=-0.400, p<0.001) [41]. Sales-Balaguer et al confirmed the association between low HGT and both myosteatosis and sarcopenia [47]. Dong et al. highlighted the lack of consensus regarding the predictive value of different functional parameters for postoperative complications. Indeed, while low SMD and 6MWT are associated with post-operative complications in univariate analysis, skeletal muscle index (SMI) and HGT seem superior (in multivariate analysis) in predicting surgical morbidity. Conversely, the team found a greater impact of SMD and 6MWT than SMI and HGT on survival [40].

Regarding complications, Carvalho et al. and Lin et al. identified a correlation between low HGT and low SMI or SMD in predicting postoperative complications. However, only SMD was found to be predictive of severe complications [35, 37].

6) Impact of muscle parameters on treatment’s morbidity in oesophagogastric cancer.

An evaluation of the impact of sarcopenia and myosteatosis on treatment was conducted in 15 studies. Details are provided in Table 3.

Table 3: Relationship between myosteatosis and treatment’s outcomes, muscle function and immune-inflammatory markers

|

First author (Journal – year) |

Muscle functional testing |

Inflammatory markers |

Treatment complications |

||||

|

Surgery |

Non surgical |

||||||

|

Bir Yucel K (Nutr Cancer – 2023) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

Low PNI had an impact on OS and PFS |

NA |

NA |

||

|

15 (7.8-22.1) p=0.003 |

|||||||

|

9 (3.9-14) p=0.018 |

|||||||

|

NLR, PLR SII have no impact. |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

||||

|

Carvalho A (PLoS ONE – 2021) |

Myosteatosis |

Low function (HGT <27 (M) or <16 (F))+ low SMI or low SMD is an independent risk factor for postoperative complication |

NA |

Myosteatosis is an independent risk factor for complications (≥grade 2) |

NA |

||

|

5.74 (1.28-25.64) p=0.022 |

7.82 (1.5-40.88) p=0.015 |

||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

Sarcopenia is not associated with complications (≥grade 2) |

NA |

||||

|

2.38 (0.65;8.75) p=0.19 |

|||||||

|

Daly L (J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle – 2019) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Change per 100 days |

|||

|

Skeletal muscle mass: |

|||||||

|

1) -6.1 cm³ (-7.7 to -4.4) p<0.001 |

|||||||

|

2) Neoadjuvant vs palliative treatment: -6.6 cm² (-10.2 to -3.1) p<0.001 |

|||||||

|

Dijksterhuis W (J cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle – 2019) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Grade III-IV toxicity |

||

|

Univariable analysis: 1.81 (0.75-4.37) p=0.186 |

|||||||

|

Multivariable analysis: 1.75 (0.72-4.28) p=0.219 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Grade III-IV toxicity |

|||

|

Univariable analysis: 0.88 0.37–2.11 p=0.778 |

|||||||

|

Multivariable analysis: 0.87 0.36–2.11 p=0.764 |

|||||||

|

Ding P (Eur J Clin Invest – 2024) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

Myosteatosis is associated with overall complications (p<0.001), severe complications (p=0.002), readmission (p=0.003), unplanned ICU transfers (p=0.003). Myosteatosis is an independent risk factor for postoperative and severe complications (p=0.001 and p=0.008). |

NA |

||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|||

|

Dong QT (Clin Nutr – 2021) |

Myosteatosis |

Low HGT (<26 kg (M) or <18 kg (F) and low gait speed (<0.8m/s) are associated with postoperative complications |

NA |

Low SMD is associated with postoperative complications |

NA |

||

|

35.1 vs 19.3% p<0.001 and 33.2 vs 21.6% p<0.001 but only low HGT is an independent risk factor for postoperative complications |

28 vs 21% p=0.006 |

||||||

|

2.132 (1.597-2.846) p<0.001 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

Low SMI is associated with postoperative complications 31.1 vs 21% p<0.001 |

NA |

||||

|

Eo W (J Cancer – 2020) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NLR >3.26 has an impact on OS and DFS |

NA |

NA |

||

|

P<0.0001 and p<0.0001 |

|||||||

|

LMR <2.79 has an impact on OS and DFS |

|||||||

|

P<0.0001 and p<0.0001 |

|||||||

|

PLR>188.82 has an impact on OS |

|||||||

|

P=0.0277 |

|||||||

|

Only NLR on multivariable analysis is an independent risk factor of OS |

|||||||

|

1.27 (1.06-1.51) p=0.0081 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

||||

|

Gabiatti CTB (Cancer Med – 2019) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

OS and PFS |

NA |

NA |

||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|||

|

Lascala F (Eur J Clin Nutr – 2023) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

1) Myosteatosis, PNI, LMR, PLR have an impact on OS. |

NA |

NA |

||

|

2) Myosteatosis, PNI and LMR have an impact on DFS. |

|||||||

|

3) NLR>2.3 and myosteatosis: |

|||||||

|

· DFS2.77 (1.54-5) p=0.001 |

|||||||

|

· OS 3.31 (1.79-6.15) p<0.001 |

|||||||

|

4) LMR<3.3 and myosteatosis : |

|||||||

|

· DFS 2.49 (1.41-4.4) p=0.002 |

|||||||

|

· OS 3.81 (2.07-7.01) p<0.001 |

|||||||

|

5) PLR > 150 and myosteatosis: |

|||||||

|

· DFS 2.04 (1.13-3.69) p=0.019 |

|||||||

|

· OS 2.87 (1.54-5.34) p=0.001 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|||

|

Li Y (Nutrition – 2022) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

PNI >40 is an independent risk factor for myosteatosis: |

NA |

NA |

||

|

2.46 (1.07-5.67) p=0.03 |

|||||||

|

PLR, NLR, LMR, SIInot associated with myosteatosis |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

PLR, NLR, NPR, LMR, SII and PNI are independent risk factors for sarcopenia: 3.46 (1.65-7.27) p<0.001 |

||||||

|

Lin J (J Surg Res – 2019) |

Myosteatosis |

Low HGT is associated with postoperative complications |

NA |

Low HUAC is associated with postoperative complications |

NA |

||

|

2.16 (1.42-3.28) p<0.001 |

1.61 (1.09-2.40) p=0.021 |

||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

Low SMI is associated with postoperative complications 1.91 (1.28-2.85) p=0.001 |

||||||

|

Lu J (Ann Surg Oncol – 2018) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

High NLR (>5) is not associated with postoperative complications |

No impact of myosteatosis (HUAC) on overall or severe postoperative complications |

NA |

||

|

Low TPG is an independent risk factor for overall and severe complications |

|||||||

|

P=0.033 and P=0.01 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

No impact of sarcopenia (TPA) on overall or severe postoperative complications. |

|||||

|

Low TPG is an independent risk factor for overall and severe complications |

|||||||

|

P=0.033 and P=0.01 |

|||||||

|

Murnane LC (Eur J Sug Oncol – 2021) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

Overall complications |

NA |

||

|

63.9 vs 38.3% p=0.014 |

|||||||

|

Severe complications (≥grade 3) |

|||||||

|

26.2 vs 8.5% p=0.013 |

|||||||

|

Anastomotic leak |

|||||||

|

14.8 vs 2.1% p=0.041 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|||

|

Park HS (Ann Surg Oncol – 2018) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

No impact of NLR on oncological outcomes |

NA |

NA |

||

|

Sarcopenia |

|||||||

|

Park JS (J Gastrointest Surg – 2024) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

Myosteatosis is an independent risk factor for major complications (p=0.032). Myosteatosis is associated with higher postoperative 30-day mortality (p=0.048). |

NA |

||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|||

|

Srpcic M (Radiol Oncol – 2020) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

Overall complications |

NA |

||

|

44. vs 49.3% p=0.570 |

|||||||

|

Conduit complications |

|||||||

|

6.9 vs 23.6% p=0.005 |

|||||||

|

Respiratory complications |

|||||||

|

23.6 vs 30.0% p=0.406 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

Overall complications |

NA |

|||

|

47.8 vs 46.6% p=0.911 |

|||||||

|

Conduit complications |

|||||||

|

17.4 vs 14.7% p=0.738 |

|||||||

|

Respiratory complications |

|||||||

|

21.7 vs 18.1% p=0.711 |

|||||||

|

Waki Y (World J Surg – 2019) |

Myosteatosis |

Low HGT in myosteatosis patient p<0.001 |

NA |

High IMAC is associated with postoperative complications (≥grade 2) 39.8 vs 25.6% p=0.012 |

NA |

||

|

Low HGT is associated with OS |

|||||||

|

1.710 (1.138-2.570) p=0.007 |

|||||||

|

No impact of HGT on cancer specific survival |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

||||

|

Watanabe J (World J Surg – 2021) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

No impact of myosteatosis (IMAC) on postoperative complications (≥grade 2) |

NA |

||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

No impact of sarcopenia on postoperative complications (≥grade 2) |

NA |

|||

|

West MA (J Surg Oncol – 2021) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Neoadjuvant treatments impact’s on myosteatosis |

||

|

19.6 vs 23.4 % p=0.31 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Neoadjuvant treatments impact’s on sarcopenia |

|||

|

25.5 vs 36.5% p<0.0001 |

|||||||

|

Yang N (Nutrition – 2024) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Neoadjuvant treatments impact’s on myosteatosis |

||

|

40.31 vs 33.72% |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

Neoadjuvant treatments impact’s on sarcopenia |

|||

|

23.26 vs 26.74% |

|||||||

|

Zhang Y (Curr Oncol – 2018) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

No correlation between CRP, RBP and myosteatosis |

Overall complications |

NA |

||

|

38.2 vs 4 % p=0.002 |

|||||||

|

Myosteatosis is an independent risk factor for overall complications |

|||||||

|

12.7 (1.6 - 93.0) p=0.017 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

No correlation between CRP, RBP and sarcopenia |

Overall complications |

NA |

|||

|

62.5 vs 27.3% p=0.001 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia is an independent risk factor for overall complications |

|||||||

|

3.4 (1.3 - 8.8) p=0.013 |

|||||||

|

Zhuang C (Surgery US – 2019) |

Myosteatosis |

NA |

NA |

Overall complications |

NA |

||

|

32.5 vs 17.8% p<0.001 |

|||||||

|

Severe complications (≥grade 3) |

|||||||

|

10.9 vs 2.9% p<0.001 |

|||||||

|

Myosteatosis is an independent risk factor for severe complications: |

|||||||

|

3.522 (1.944-6.380) p<0.001 |

|||||||

|

Sarcopenia |

NA |

NA |

NA |

NA |

|||

CRP = C-reactive protein ; CSS = cancer-specific survival ; CT = chemotherapy ; dRCT = definitive radiochemotherapy ; HGT = hand grip test ; HUAC = Hounsfield unit average calculation ; LMR = lymphocyte to monocyte ratio ; NLR = neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio ; NPR = neutrophil to platelet ratio ; OS = overall survival ; PLR = platelet to lymphocyte ratio ; PNI = prognostic nutritional index ; RBP = retinol-binding protein ; RCT = radiochemotherapy ; RFS = recurrence-free survival ; SII = systemic immuno-inflammation index; TPA = total psoas area ; TPG = total psoas gauge (TPA X HUAC)

The evolution of the body component was analysed in 4 studies before and after the different neoadjuvant treatment modalities [20, 25, 27, 48]: one evaluated outcomes before and after neoadjuvant treatment [20], another at diagnostic and 100 days after treatment [25], another before and after chemotherapy for metastatic cancers [27], and the last before and after radiotherapy [48]. West et al and Daly et al reported a significant impact of systemic treatments on both muscle mass and muscle quality [20, 25]. Daly et al observed a greater increase in sarcopenia among patients undergoing neoadjuvant treatment compared to those receiving palliative care [25]. Yang et al found an increase of sarcopenia prevalence but a decrease myosteatosis prevalence, whereas Dijksterhuis et al noted a decrease in myosteatosis over time in patients receiving palliative treatment [27]. Thus, all demonstrated an increase in sarcopenia due to muscle mass loss during neoadjuvant treatment. Myosteatosis appeared to follow a similar trend under the influence of non-surgical treatments [20, 25, 27], except in the study by Yang et al, which observed a slight, non-significant decrease [48].

Adverse events related to neoadjuvant or systemic treatment in patients with myosteatosis or sarcopenia were analysed in one study. Dijksterhuis et al observed a significant correlation between low SMD and toxicity grade 3 or 4. Others parameters were not associated with toxicity [27]. No data were found on the impact of surgery on the body component. Studies have focused on correlations between sarcopenia/myosteatosis and the occurrence of complications. Surgical postoperative complications were assessed in 12 studies. Most of them reported a negative impact of myosteatosis on surgical complications in patients who underwent surgery. Low SMD were strongly associated with surgical complications, including overall complications [8, 21, 32, 33, 35, 37, 40, 41, 50], severe complications (≥ grade 2-3) [8, 32, 35, 41, 46, 50], and anastomotic leaks [8]. Srpcic et al, however, found no association with respiratory complications and even reported fewer conduit complications in the myosteatosis group compared with patients without myosteatosis (6,9 vs 23,9 %, OR 0,238 (0,082-0,692), p=0,005) [21]. Conversely, two studies did not identify any impact of low SMD on surgical outcomes [43, 44]. Lu et al, however, highlighted a significant impact of the total Psoas Gauge (TPG), defined by the product of the Total Psoas Area (”TPA”) by the density measurement in Hounsfield units (“HUAC”) on severe and overall complications for sarcopenia et myosteatosis.

Sarcopenia was associated with overall postoperative complications in several studies [33, 37, 40, 50], although others did not report any significant relationship [21, 35, 43, 44].

Discussion

This systematic review highlights the prognostic significance of myosteatosis in oesophagogastric cancer and its treatment while underscoring the challenges in interpreting existing data. The considerable heterogeneity in defining body composition variables, analytical methodologies, and study populations complicates the interpretation of findings and does not allow all the results to be presented in a uniform and standardised manner.

Myosteatosis can be assessed non-invasively through imaging techniques such as computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and quantitative ultrasound. Each method has its advantages and limitations [12]. While there is no gold standard for measuring myosteatosis, CT remains the most commonly used tool in large-scale research. However, CT provides only an indirect assessment by analysing muscle density and cannot differentiate between intermuscular and intramuscular fat [14, 54, 55], Although Hounsfield unit (HU) cut-off values have been linked to prognostic outcomes in cancer populations [52], no universally accepted cut-offs exist, leading to inconsistencies in defining sarcopenia and myosteatosis, thereby complicating data comparison.

The prevalence of myosteatosis remains debated due to the lack of standardised measurement methods, but evidence suggests it is as significant as sarcopenia. Some studies report that up to 84% of patients with oesophagogastric cancer exhibit myosteatosis. In our review, sarcopenia prevalence ranged from 15.4% to 69.9%, while myosteatosis prevalence varied between 11.0% and 84.0%. These discrepancies stem from multiple factors. Firstly, many studies do not stratify patients by age, despite age-related progression of muscle mass and myosteatosis. Secondly, inconsistencies in cut-off values for defining these conditions lead to differing prevalence estimates. Thirdly, comorbidities such as diabetes or neuromuscular diseases could also influence muscle measurements. Finally, variations in tumour stages and treatment regimens impact muscle health and, consequently, prevalence estimates.

Examining myosteatosis alongside sarcopenia offers a more comprehensive understanding of muscle health in cancer patients. For reference, Martin's criteria for defining sarcopenia are based on gender and BMI, and solely on BMI for measuring myosteatosis. Thus, sarcopenia is defined without measuring muscle strength, which is usually recommended when diagnosing sarcopenia. In clinical practice, sarcopenia is often assessed without considering muscle strength, in which case it is referred to as myopenia [54, 55]. While sarcopenia refers to the loss of muscle mass and function, myosteatosis is characterised by pathological fat accumulation within muscle tissue, which can occur even in the absence of significant muscle mass reduction. Their coexistence exacerbates muscle weakness, accelerates functional decline, and negatively affects overall health outcomes. However, it remains unclear whether sarcopenia or myosteatosis serves as the better prognostic indicator [56]. Moreover, few studies have focused on the relationship between muscle and its function in oesogastric cancer. Although a potential link between muscle function and myosteatosis exists, the lack of data prevents any firm conclusions. Further research is needed to explore this association. Prospective studies combining body composition imaging and muscle function assessment would be valuable. Such investigations could provide a more comprehensive understanding of muscle health in this context. Importantly, low muscle density has been associated with poorer survival compared to normal muscle attenuation. Most studies in this review highlight the negative impact of myosteatosis and/or sarcopenia on overall survival (OS) and/or progression-free or disease-free survival (PFS/DFS). However, some studies report no significant association between myosteatosis and OS [27, 30, 34, 36, 46]. Interestingly, Gabiatti et al. observed improved OS and PFS in patients with myosteatosis undergoing definitive chemoradiotherapy, provided systemic inflammation (NLR < 2.8) was absent [23]. This unexpected finding suggests a dual role of visceral fat in malignancies: it serves as an energy reserve and indicator of nutritional status, but also contributes to pro-inflammatory processes and tumour growth. Systemic inflammation may further exacerbate survival outcomes by promoting insulin resistance or impairing mitochondrial oxidation [23]. However, Gabiatti’s study focused exclusively on patients treated with chemoradiotherapy, a group potentially too frail for multimodal treatment, including surgery, which remains the standard of care.

As shown in this review, tumour-associated inflammation plays a crucial role in cancer initiation, progression, and metastasis. Several inflammatory markers, such as CRP, PLS, PNI, NLR, NPR, and LMR, have been strongly linked to poor outcomes in oesophagogastric cancer [30, 54, 55]. Beyond its systemic effects, inflammation contributes to skeletal muscle depletion and cachexia [56, 57]. Emerging mechanistic insights suggest that skeletal muscle functions as a secretory organ, releasing myokines that regulate inflammation [58]. In myosteatosis, impaired muscle quality may disrupt myokine production, exacerbating pro-inflammatory cytokine activity. Evidence from colorectal cancer cohorts has shown a direct association between myosteatosis, increased NLR, and low albumin levels—both markers of systemic inflammation [59].

Further research should investigate the role of local muscle inflammation in the development of myosteatosis and its potential impact on cancer progression. Understanding the crosstalk between intramuscular inflammatory pathways and tumour-related systemic inflammation could provide insights into disease mechanisms and reveal novel therapeutic strategies.

The pathophysiological mechanisms behind increased intramyocellular lipid deposits in cancer-related weight loss are not yet fully understood, though enhanced lipolysis, insulin resistance, and impaired mitochondrial oxidation are commonly implicated [57]. Recent mouse model studies suggest cancer cachexia induces myosteatosis via dysregulated lipid metabolism and altered lipid droplet-associated proteins. Myosteatosis may impair fatty acid oxidation by reducing lipid droplet interactions with mitochondria, thereby worsening metabolic dysfunction [16]. Parallels can also be drawn with cancer-associated adipocytes (CAAs) present in the tumour microenvironment, which exhibit similar morphological and functional changes. Research in breast cancer patients has shown that CAAs enhance tumour aggressiveness by altering their phenotype upon contact with cancer cells, secreting proteases and inflammatory cytokines (e.g. IL-6, IL-1beta) [58]. However, these mechanisms require further investigation in human studies.

Our review found a strong association between myosteatosis and treatment outcomes, although some studies failed to establish such links. The mechanisms underlying the impact of myosteatosis or sarcopenia on postoperative complications remain uncertain, but two hypotheses have been proposed. Firstly, myosteatosis reflects a decline in muscle quality, leading to reduced strength and mobility [59]. Secondly, it is linked to systemic inflammation, which is exacerbated by the catabolic stress of surgery and postoperative complications [60]. Beyond general complications, the association between myosteatosis and severe surgical complications—known to impact oncological survival—is particularly significant. This suggests that improving patients’ muscle status prior to surgery could enhance postoperative outcomes and treatment tolerance. In a non-oncological geriatric population, Taaffe et al. demonstrated that exercise significantly improved skeletal muscle density (HU) and quadriceps strength [61]. Similarly, Shaver et al. found an association between myosteatosis and reduced physical function in head and neck cancer patients, indicating that prehabilitation programmes could optimise functional capacity [62]. In oesophageal cancer, prehabilitation has been shown to reduce muscle mass loss during neoadjuvant therapy while also decreasing subcutaneous and intra-abdominal fat, which correlates with a lower risk of postoperative complications [63]. Prospective studies will make it possible to verify the beneficial impact of these improved parameters on outcomes such as mortality in oesophagogastric cancer. Recently, multimodal prehabilitation interventions—including nutrition and exercise—prior to oesophagogastric cancer surgery have been shown to improve fitness and postoperative outcomes [64]. Prehabilitation may help limit muscle mass decline and reduce visceral adipose tissue [63], thereby lowering treatment-related toxicity. Given that many patients are elderly and weakened by disease, physical preparation before treatment is crucial for improving postoperative recovery and overall resilience to oncological therapies.

Conclusion

This review highlights the significant impact of myosteatosis on oncological and treatment outcomes in patients with oesophagogastric cancer, in addition to sarcopenia (already well known and described). Further prospective studies are essential to uncover the mechanisms by which myosteatosis influences cancer progression, paving the way for the development of targeted interventions in cancer care.

Conflict Of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

YD conceived and designed the analysis, collected data, performed the analysis and wrote the manuscript. NL conceived and designed the analysis, collected data, performed the manuscript review with revisions for important intellectual content. MVD conceived and designed the analysis, performed the manuscript review with revisions for important intellectual content. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding Information

This work was supported by the IRA II grant (Centre du Cancer “Institut Roi Albert II”, Cliniques universitaires Saint-Luc) attributed to the principal author.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This retrospective study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Hospital-faculty Ethics Committee Saint-Luc – UCL (2023/31MAI/240 – B403).

References

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. International journal of cancer 144 (2019): 1941-1953.

- Arnold M, Morgan E, Bardot A, et al. International variation in oesophageal and gastric cancer survival 2012-2014: differences by histological subtype and stage at diagnosis (an ICBP SURVMARK-2 population-based study). Gut 71 (2022): 1532-1543.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, et al. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age and ageing 48 (2019): 601.

- Goodpaster BH, Carlson CL, Visser M, et al. Attenuation of skeletal muscle and strength in the elderly: The Health ABC Study. Journal of applied physiology (Bethesda, Md: 1985) 90 (2001): 2157-2165.

- Awad S, Tan BH, Cui H, et al. Marked changes in body composition following neoadjuvant chemotherapy for oesophagogastric cancer. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 31 (2012): 74-77.

- Prado CM, Baracos VE, McCargar LJ, et al. Body composition as an independent determinant of 5-fluorouracil-based chemotherapy toxicity. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 13 (2007): 3264-3268.

- Prado CM, Baracos VE, McCargar LJ, et al. Sarcopenia as a determinant of chemotherapy toxicity and time to tumor progression in metastatic breast cancer patients receiving capecitabine treatment. Clinical cancer research: an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 15 (2009): 2920-2926.

- Murnane LC, Forsyth AK, Koukounaras J, et al. Myosteatosis predicts higher complications and reduced overall survival following radical oesophageal and gastric cancer surgery. European journal of surgical oncology: the journal of the European Society of Surgical Oncology and the British Association of Surgical Oncology 47 (2021): 2295-2303.

- Kamiliou A, Lekakis V, Xynos G, et al. Prevalence of and Impact on the Outcome of Myosteatosis in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Cancers 16 (2024).

- Pozzuto L, Silveira MN, Mendes MCS, et al. Myosteatosis Differentially Affects the Prognosis of Non-Metastatic Colon and Rectal Cancer Patients: An Exploratory Study. Frontiers in oncology 11 (2021): 762444.

- Yamashita S, Iwahashi Y, Miyai H, et al. Myosteatosis as a novel prognostic biomarker after radical cystectomy for bladder cancer. Scientific reports 10 (2020): 22146.

- Correa-de-Araujo R, Addison O, Miljkovic I, et al. Myosteatosis in the Context of Skeletal Muscle Function Deficit: An Interdisciplinary Workshop at the National Institute on Aging. Frontiers in physiology 11 (2020): 963.

- Mangner N, Winzer EB, Linke A, et al. Locomotor and respiratory muscle abnormalities in HFrEF and HFpEF. Frontiers in cardiovascular medicine 10 (2023): 1149065.

- Henin G, Loumaye A, Leclercq IA, et al. Myosteatosis: Diagnosis, pathophysiology and consequences in metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. JHEP reports: innovation in hepatology 6 (2024): 100963.

- Stoll JR, Vaidya TS, Mori S, et al. Association of interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α with mortality in hospitalized patients with cancer. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology 84 (2021): 273-282.

- Cardaci TD, VanderVeen BN, Huss AR, et al. Decreased skeletal muscle intramyocellular lipid droplet-mitochondrial contact contributes to myosteatosis in cancer cachexia. American journal of physiology Cell physiology 327 (2024): 684-697.

- Dondero K, Friedman B, Rekant J, et al. The effects of myosteatosis on skeletal muscle function in older adults. Physiological reports 12 (2024): 16042.

- Chen YF, Lee CW, Wu HH, et al. Immunometabolism of macrophages regulates skeletal muscle regeneration. Frontiers in cell and developmental biology 10 (2022): 948819.

- Kitajima T, Okugawa Y, Shimura T, et al. Combined assessment of muscle quality and quantity predicts oncological outcome in patients with esophageal cancer. American journal of surgery 225 (2023): 1036-1044.

- West MA, Baker WC, Rahman S, et al. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing has greater prognostic value than sarcopenia in oesophago-gastric cancer patients undergoing neoadjuvant therapy and surgical resection. Journal of surgical oncology 124 (2021): 1306-1316.

- Srpcic M, Jordan T, Popuri K, et al. Sarcopenia and myosteatosis at presentation adversely affect survival after esophagectomy for esophageal cancer. Radiology and oncology 54 (2020): 237-246.

- Zhou C, Foster B, Hagge R, et al. Opportunistic body composition evaluation in patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma: association of survival with (18)F-FDG PET/CT muscle metrics. Annals of nuclear medicine 34 (2020): 174-181.

- Gabiatti CTB, Martins MCL, Miyazaki DL, et al. Myosteatosis in a systemic inflammation-dependent manner predicts favorable survival outcomes in locally advanced esophageal cancer. Cancer medicine 8 (2019): 6967-6976.

- Tamandl D, Paireder M, Asari R, et al. Markers of sarcopenia quantified by computed tomography predict adverse long-term outcome in patients with resected oesophageal or gastro-oesophageal junction cancer. European radiology 26 (2016): 1359-1367.

- Daly LE, ÉB NB, Power DG, et al. Loss of skeletal muscle during systemic chemotherapy is prognostic of poor survival in patients with foregut cancer. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle 9 (2018): 315-325.

- Dohzono S, Sasaoka R, Takamatsu K, et al. Prognostic value of paravertebral muscle density in patients with spinal metastases from gastrointestinal cancer. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 27 (2019): 1207-1213.

- Dijksterhuis WPM, Pruijt MJ, van der Woude SO, et al. Association between body composition, survival, and toxicity in advanced esophagogastric cancer patients receiving palliative chemotherapy. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle 10 (2019): 199-206.

- Bir Yucel K, Karabork Kilic AC, Sutcuoglu O, et al. Effects of Sarcopenia, Myosteatosis, and the Prognostic Nutritional Index on Survival in Stage 2 and 3 Gastric Cancer Patients. Nutrition and cancer 75 (2023): 368-375.

- Lascala F, da Silva Moraes BK, Mendes MCS, et al. Prognostic value of myosteatosis and systemic inflammation in patients with resectable gastric cancer: A retrospective study. European journal of clinical nutrition (2023): 116-126.

- Li Y, Wang WB, Yang L, et al. The combination of body composition conditions and systemic inflammatory markers has prognostic value for patients with gastric cancer treated with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif) 93 (2022): 111464.

- Kusunoki Y, Okugawa Y, Toiyama Y, et al. Modified intramuscular adipose tissue content as a feasible surrogate marker for malnutrition in gastrointestinal cancer. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 40 (2021): 2640-2653.

- Zhuang CL, Shen X, Huang YY, et al. Myosteatosis predicts prognosis after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A propensity score-matched analysis from a large-scale cohort. Surgery 166 (2019): 297-304.

- Zhang Y, Wang JP, Wang XL, et al. Computed tomography-quantified body composition predicts short-term outcomes after gastrectomy in gastric cancer. Current oncology (Toronto, Ont) 25 (2018): 411-422.

- He M, Chen ZF, Zhang L, et al. Associations of subcutaneous fat area and Systemic Immune-inflammation Index with survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer receiving dual PD-1 and HER2 blockade. Journal for immunotherapy of cancer 11 (2023).

- Carvalho ALM, Gonzalez MC, Sousa IM, et al. Low skeletal muscle radiodensity is the best predictor for short-term major surgical complications in gastrointestinal surgical cancer: A cohort study. PloS one 16 (2021): e0247322.

- Park HS, Kim HS, Beom SH, et al. Marked Loss of Muscle, Visceral Fat, or Subcutaneous Fat After Gastrectomy Predicts Poor Survival in Advanced Gastric Cancer: Single-Center Study from the CLASSIC Trial. Ann Surg Oncol 25 (2018): 3222-3230.

- Lin J, Zhang W, Chen W, et al. Muscle Mass, Density, and Strength Are Necessary to Diagnose Sarcopenia in Patients With Gastric Cancer. The Journal of surgical research 241 (2019): 141-148.

- Hacker UT, Hasenclever D, Linder N, et al. Prognostic role of body composition parameters in gastric/gastroesophageal junction cancer patients from the EXPAND trial. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle 11 (2020): 135-144.

- Eo W, Kwon J, An S, et al. Clinical Significance of Paraspinal Muscle Parameters as a prognostic factor for survival in Gastric Cancer Patients who underwent Curative Surgical Resection. Journal of Cancer 11 (2020): 5792-5801.

- Dong QT, Cai HY, Zhang Z, et al. Influence of body composition, muscle strength, and physical performance on the postoperative complications and survival after radical gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A comprehensive analysis from a large-scale prospective study. Clinical nutrition (Edinburgh, Scotland) 40 (2021): 3360-3369.

- Waki Y, Irino T, Makuuchi R, et al. Impact of Preoperative Skeletal Muscle Quality Measurement on Long-Term Survival After Curative Gastrectomy for Locally Advanced Gastric Cancer. World journal of surgery 43 (2019): 3083-3093.

- Hayashi N, Ando Y, Gyawali B, et al. Low skeletal muscle density is associated with poor survival in patients who receive chemotherapy for metastatic gastric cancer. Oncology reports 35 (2016): 1727-1731.

- Watanabe J, Osaki T, Ueyama T, et al. The Combination of Preoperative Skeletal Muscle Quantity and Quality is an Important Indicator of Survival in Elderly Patients Undergoing Curative Gastrectomy for Gastric Cancer. World journal of surgery 45 (2021): 2868-2877.

- Lu J, Zheng ZF, Li P, et al. A Novel Preoperative Skeletal Muscle Measure as a Predictor of Postoperative Complications, Long-Term Survival and Tumor Recurrence for Patients with Gastric Cancer After Radical Gastrectomy. Ann Surg Oncol 25 (2018):439-448.

- An S, Eo W, Kim YJ. Muscle-Related Parameters as Determinants of Survival in Patients with Stage I-III Gastric Cancer Undergoing Gastrectomy. Journal of Cancer 12 (2021): 5664-5673.

- Park JS, Colby M, Spencer J, et al. Radiologic myosteatosis predicts major complication risk following esophagectomy for cancer: a multicenter experience. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery: official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract 28 (2024): 1861-1869.

- Sales-Balaguer N, Sorribes-Carreras P, Morillo Macias V. Diagnosis of Sarcopenia and Myosteatosis by Computed Tomography in Patients with Esophagogastric and Pancreatic Cancer. Cancers 16 (2024).

- Yang N, Zhou P, Lyu J, et al. Prognostic value of sarcopenia and myosteatosis alterations on survival outcomes for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma before and after radiotherapy. Nutrition (Burbank, Los Angeles County, Calif) 127 (2024): 112536.

- Du Z, Xiao Y, Deng G, et al. CD3+/CD4+ cells combined with myosteatosis predict the prognosis in patients who underwent gastric cancer surgery. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle 15 (2024): 1587-1600.

- Ding P, Wu J, Wu H, et al. Myosteatosis predicts postoperative complications and long-term survival in robotic gastrectomy for gastric cancer: A propensity score analysis. European journal of clinical investigation 54 (2024): 14201.

- Deng GM, Song HB, Du ZZ, et al. Evaluating the influence of sarcopenia and myosteatosis on clinical outcomes in gastric cancer patients undergoing immune checkpoint inhibitor. World journal of gastroenterology 30 (2024): 863-880.

- Martin L, Birdsell L, Macdonald N, et al. Cancer cachexia in the age of obesity: skeletal muscle depletion is a powerful prognostic factor, independent of body mass index. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 31 (2013): 1539-1547.

- Buzby GP, Mullen JL, Matthews DC, et al. Prognostic nutritional index in gastrointestinal surgery. American journal of surgery 139 (1980): 160-167.

- Goffaux A, Delorme A, Dahlqvist G, et al. Improving the prognosis before and after liver transplantation: Is muscle a game changer? World journal of gastroenterology 28 (2022): 5807-5817.

- Henin G, Lanthier N. What references and what gold standard should be used to assess myosteatosis in chronic liver disease? Journal of hepatology 81 (2024): 273-274.

- Lanthier N, Stärkel P, Dahlqvist G. Frailty, sarcopenia and mortality in cirrhosis: what is the best assessment, how to interpret the data correctly and what interventions are possible? Clinics and research in hepatology and gastroenterology 45 (2021): 101661.

- Mendes MC, Pimentel GD, Costa FO, Carvalheira JB. Molecular and neuroendocrine mechanisms of cancer cachexia. The Journal of endocrinology 226 (2015) :29-43.

- Dirat B, Bochet L, Dabek M, et al. Cancer-associated adipocytes exhibit an activated phenotype and contribute to breast cancer invasion. Cancer research 71 (2011): 2455-2465.

- Zamboni M, Gattazzo S, Rossi AP. Myosteatosis: a relevant, yet poorly explored element of sarcopenia. European geriatric medicine 10 (2019): 5-6.

- Persson HL, Sioutas A, Kentson M, et al. Skeletal Myosteatosis is Associated with Systemic Inflammation and a Loss of Muscle Bioenergetics in Stable COPD. Journal of inflammation research 15 (2022): 4367-4384.

- Taaffe DR, Henwood TR, Nalls MA, et al. Alterations in muscle attenuation following detraining and retraining in resistance-trained older adults. Gerontology 55 (2009): 217-223.

- Shaver AL, Noyes K, Platek ME, et al. Cross-sectional analysis of myosteatosis and physical function in pretreatment head and neck cancer patients. Supportive care in cancer: official journal of the Multinational Association of Supportive Care in Cancer 30 (2022): 3401-3408.

- Halliday LJ, Boshier PR, Doganay E, et al. The effects of prehabilitation on body composition in patients undergoing multimodal therapy for esophageal cancer. Diseases of the esophagus: official journal of the International Society for Diseases of the Esophagus 36 (2023).

- Pedersen BK, Febbraio MA. Muscles, exercise and obesity: skeletal muscle as a secretory organ. Nature reviews Endocrinology 8 (2012): 457-465.

Impact Factor: * 4.1

Impact Factor: * 4.1 Acceptance Rate: 74.74%

Acceptance Rate: 74.74%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks