Inducing Demand for Abortion in the Absence of Medical Necessity: Planned Parenthood and Abortion Drugs

James Studnicki*,1,2, John W. Fisher1, Elyse Gaitan1, Tessa Longbons Cox1, Genevieve Plaster1

1Charlotte Lozier Institute, Arlington, VA

2University of North Carolina, Charlotte, NC

*Corresponding author: James Studnicki, Charlotte Lozier Institute, 2776 S. Arlington Mill Dr. Box #803, Arlington, VA 22206

Received: 12 May 2025; Accepted: 22 May 2025; Published: 09 June 2025

Article Information

Citation: James Studnicki, John W. Fisher, Elyse Gaitan, Tessa Longbons Cox, Genevieve Plaster. Inducing Demand for Abortion in the Absence of Medical Necessity: Planned Parenthood and Abortion Drugs. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences 8 (2025): 516-522.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

After nearly three decades of persistent decline in the U.S., the volume and rate of induced abortions turned unexpectedly upward in 2018. Given the discretionary preferential nature of the abortion decision, supply-induced demand (SID) is likely an important contributor to this abrupt change. We discuss the dominant provider (Planned Parenthood Federation of America) and abortion method (medical abortion), and the means by which they enhance demand. Their combined efforts and evolution have enabled the survival of abortion services even during three decades of contraction and the subsequent current period of growth.

Keywords

<p>induced abortion, abortion rates, supply-induced demand (SID), medical necessity, discretionary services</p>

Article Details

Introduction

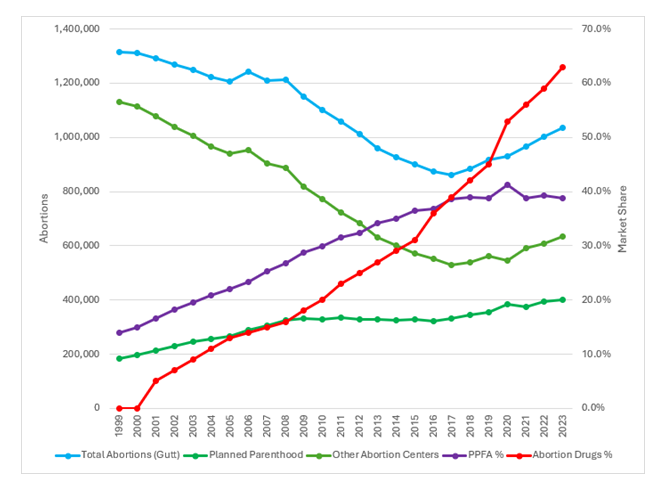

In 1973, the United States Supreme Court ruled (Roe v. Wade, 410 U.S. 113) that the right to an induced abortion was protected by the Constitution. For the next 17 years, the number of abortions in the United States steadily increased, peaking in 1990 at about 1.6 million [1]. From that point, both total abortions and the abortion rate began a steady decline that lasted nearly three decades. In 2018, however, this long-term decline veered sharply upward in a new direction which has been maintained through 2023. The increase in total annual abortions as estimated by the Guttmacher Institute from 2017 (862,320) to 2023 (1,037,000) was 20.3% [2, 3]. A graph of total U.S. abortions from 1999 to 2023 illustrates a characteristic “hockey stick” shape with a stable downward “handle” (1999-2017) abruptly turning upward (2018-2023) as the “blade” (Figure 1 and Table 1). In this policy perspective, we consider supply-induced demand for abortion as one of the important contributors to this unexpected reversal. In particular, we focus the discussion on the characteristics, motivation and behavior of the nation’s dominant abortion provider, the Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA); and the evolution, nature, and growth of the now dominant method of abortion provision via the administration of mifepristone and misoprostol (i.e., abortion drugs).

Table 1: Total abortions, Planned Parenthood abortions, non-Planned Parenthood abortions, and drug-induced abortions, 1999-2023. NA = not available.

|

Year |

Total Abortions (Guttmacher)* |

Planned Parenthood |

Other Abortion Centers |

PPFA % |

Abortion Drugs |

Abortion Drugs % |

|

1999 |

1,314,780 |

182,792 |

1,131,988 |

13.90% |

NA |

NA |

|

2000 |

1,312,990 |

197,070 |

1,115,920 |

15.00% |

NA |

NA |

|

2001 |

1,291,000 |

213,026 |

1,077,974 |

16.50% |

70,500 |

5% |

|

2002 |

1,269,000 |

230,630 |

1,038,370 |

18.20% |

93,150 |

7% |

|

2003 |

1,250,000 |

245,092 |

1,004,908 |

19.60% |

115,800 |

9% |

|

2004 |

1,222,100 |

255,015 |

967,085 |

20.90% |

138,450 |

11% |

|

2005 |

1,206,200 |

264,943 |

941,257 |

22.00% |

161,100 |

13% |

|

2006 |

1,242,200 |

289,750 |

952,450 |

23.30% |

173,733 |

14% |

|

2007 |

1,209,640 |

305,310 |

904,330 |

25.20% |

186,367 |

15% |

|

2008 |

1,212,350 |

324,008 |

888,342 |

26.70% |

199,000 |

16% |

|

2009 |

1,151,600 |

331,796 |

819,804 |

28.80% |

212,467 |

18% |

|

2010 |

1,102,670 |

329,445 |

773,225 |

29.90% |

225,933 |

20% |

|

2011 |

1,058,490 |

333,964 |

724,526 |

31.60% |

239,400 |

23% |

|

2012 |

1,011,000 |

327,166 |

683,834 |

32.40% |

250,400 |

25% |

|

2013 |

958,700 |

327,653 |

631,047 |

34.20% |

261,400 |

27% |

|

2014 |

926,190 |

323,999 |

602,191 |

35.00% |

272,400 |

29% |

|

2015 |

899,500 |

328,348 |

571,152 |

36.50% |

281,875 |

31% |

|

2016 |

874,080 |

321,384 |

552,696 |

36.80% |

310,758 |

36% |

|

2017 |

862,320 |

332,757 |

529,563 |

38.60% |

339,640 |

39% |

|

2018 |

885,800 |

345,672 |

540,128 |

39.00% |

375,885 |

42% |

|

2019 |

916,460 |

354,871 |

561,589 |

38.70% |

412,130 |

45% |

|

2020 |

930,160 |

383,460 |

546,700 |

41.20% |

492,210 |

53% |

|

2021 |

965,773 |

374,155 |

591,618 |

38.70% |

542,373 |

56% |

|

2022 |

1,001,387 |

392,715 |

608,672 |

39.20% |

592,537 |

59% |

|

2023 |

1,037,000 |

402,230 |

634,770 |

38.80% |

642,700 |

63% |

*Guttmacher total abortion and abortion drug estimates are not available for every year; missing years were estimated via linear interpolation.

Supply-Induced Demand (SID)

Providers may attempt to induce demand for their services in order to increase volume and revenues or to promote their own preferred values beyond what would normally be expected – a phenomenon known as supply-induced demand [4-6]. Services most likely to be susceptible to supply-induced demand (SID) are discretionary in nature; i.e., those which are not essential to meet some clinically defined need but are nonetheless wanted and purchased based upon personal preferences, financial ability or perceived value by customers who are typically not fully informed [7,8]. There is no better example of a discretionary, preference-sensitive service than an induced abortion. According to publicly available data, the overwhelming percentage of induced abortions are performed on healthy mothers carrying healthy babies [9] which comports with older survey research showing that the reasons given by women who had induced abortions are mainly for preferential, elective, usually social and financial reasons [10,11]. Less than 5% of abortions are reported to involve a substantial risk to the mother’s health or life, some abnormality in the baby, other physical health concerns, or rape/incest [9]. Induced abortion has not been determined as the standard of care for any disease, illness or condition and, therefore, cannot in most cases be considered evidence-based medical practice [12].

Another characteristic of the existence of SID for abortion in the U.S. is a high variation in the incidence rates of services across population defined areas. In 2022, Missouri and South Dakota had abortion rates (abortions per 1,000 women 15-44) of less than one, 0.1 and 0.8 respectively [13]. New Mexico had the highest rate of 28.8, which is 288 times higher than Missouri’s. Some of the disparity likely indicates unmet demand for abortions in pro-life states, as Missouri and South Dakota both implemented strong pro-life protections in 2022. However, an analysis of online requests for abortion drugs before and after the Dobbs decision shows that both Missouri and South Dakota demonstrated request rates far lower than many other states with similar abortion laws [14]. Furthermore, an analysis of online abortion drug prescriptions found that very pro-abortion states received abortion drugs at a higher rate than other states [15]. This extraordinary range of demand for abortion services is strongly suggestive that provider location, investment, and inadequate attention to informed consent, rather than clinically defined medical need, are the main drivers of abortion incidence.

Planned Parenthood Federation of America

The Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA) is a non-profit organization whose mission prioritizes “advocat[ing] for public policies that protect and expand reproductive rights and access to a full range of sexual and reproductive health care services, including abortion.” [16]. As the largest abortion provider in the United States, Planned Parenthood has a significant influence on the U.S. abortion rate and strategically uses its financial resources to promote and advocate for abortion. Its 2024 annual report showed $2.5 billion in net assets, $2 billion in current annual revenue, and $27 million in excess of total revenue over expenses. The organization received $684 million in annual private contributions and bequests and $792 million from government grants and service reimbursement. PPFA is 15th on the Forbes Top 100 Largest U.S. Charities, ranking higher than the American National Red Cross (16th), American Cancer Society (25th), and American Heart Association (28th) [17].

Much of these financial resources are focused on promoting and expanding abortion, with former Planned Parenthood staff and patients recently stating that the organization has sacrificed healthcare standards in order to devote more resources to abortion advocacy at the national level [18]. PPFA’s 501(c)(3) affiliates spent almost $60 million in fiscal year 2023 on public policy programs, [19] while the 501(c)(4) advocacy and political arm, Planned Parenthood Action Fund, and related entities reported spending a record high of $69.5 million during the 2024 election cycle to support pro-choice candidates [20]. The organization’s prioritization of abortion has at times resulted in internal tension within its leadership over the course of its decades-long history, with former presidents Pamela Maraldo in 1995 and Leana Wen in 2019, both medical professionals, departing due to irreconcilable differences with the board over whether the future of the organization should be public health or abortion promotion [21, 22].

Abortion’s Role in Planned Parenthood’s Service Profile

Market share is one of the key metrics in determining the success of an organization. It demonstrates what percentage of the market potential (total services provided or products sold) is captured by the organization. Market share is also an objective way to measure reliance of the total market of clients or customers on any provider of goods or services.

For most of the services offered at their centers, Planned Parenthood provides a very tiny fraction of the national annual incidence of those services. According to Planned Parenthood’s 2023-2024 annual report, which provides service data for 2022-2023, Planned Parenthood health centers saw 2.08 million patients and provided 9.45 million services (defined as a “discrete clinical interaction)” [19]. Of total Planned Parenthood’s services, sexually transmitted infections (STI) testing and treatment accounted for the highest volume category, at 5,132,330, or 54.3% of total services. However, this represents a small percentage of total STI testing nationally. Data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System suggests that in 2017, approximately 23,398,000 American adults were tested for HIV within the past 12 months [23]. That same year, Planned Parenthood reported conducting 741,352 HIV tests [24] indicating a contribution of just 3.2% of the HIV tests conducted in the United States. Furthermore, Planned Parenthood’s contribution to STI treatment beyond testing is negligible. Of STI-related services in the 2023-2024 annual report, PPFA specified that over 99% were for testing, while less than 1% was for treatment of genital warts (HPV) and “other STI prevention and treatments” [19].

The second highest volume service group provided by PPFA was for contraception, at 24% of total services in the 2023-2024 report. However, Planned Parenthood provides services to just 11% of women enrolled in Medicaid who obtain contraception [25]. It should be noted that most of Planned Parenthood’s Medicaid contraceptive clients are concentrated in a few states including California and Washington, with Planned Parenthood accounting for less than 5% of total Medicaid contraceptive clients in over half the states. This imbalanced distribution in high-population states suggests a profit maximization strategy, rather than addressing lower volume pockets of unmet need. Planned Parenthood’s 2023-2024 report indicates that the organization’s 402,230 abortions comprised just 4.3% of total services; however, this calculation weights all clinical interactions equally, with an abortion and pregnancy test counted as two unique services, even if a pregnancy test is given to a patient as a means to confirm her pregnancy before the procedure. As a percentage of revenue, abortion is a much larger component of the group’s work, with estimates that abortion represents at least 10 percent of total revenue [26]. Abortion accounts for 96.9% of PPFA’s services related to the resolution of pregnancy, alongside miscarriage care, prenatal care, and adoption referrals – with adoption referrals accounting for only 0.5% [19].

Planned Parenthood’s annual abortion totals have increased even as total clients have fallen. From 1999 to 2023, Planned Parenthood abortions increased from 182,792 to 402,230, an increase of 120%. During the same time period, abortions performed by non-Planned Parenthood providers decreased from approximately 1,131,988 to 634,770, a decrease of 44%. As a result of these opposite and divergent trajectories in abortion volume, Planned Parenthood’s share of the U.S. abortion market went from 13.9% in 1999 to 38.8% in 2023, a noteworthy 179% increase (see Table 1). Between 1999 and 2022, Planned Parenthood’s annual clients dropped by more than 550,000, or 21%, and only increased by 1% in 2023 [19, 27]. Besides abortion, Planned Parenthood provides no services that are not easily accessible from other providers, with contraception and STI testing widely available at community health clinics [28]. Planned Parenthood has explicitly chosen to focus on abortion as central to its mission, and its increase in annual abortion totals amidst falling national abortion rates is suggestive of supply-induced demand. Planned Parenthood is also committed to abortion drugs in particular. PPFA was an early promoter and advocate of mifepristone starting in the 1980s long before the drug became available in the United States, and Planned Parenthood operated eight of the 17 abortion centers that participated in a U.S. clinical trial to facilitate United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of the drug [29, 30]. Since then, mifepristone has become an important part of Planned Parenthood’s business model. A review of Planned Parenthood’s website in February 2025 showed that 58% of Planned Parenthood brick-and-mortar abortion centers offer only drug-induced abortions, while only 42% provide surgical abortions.

Abortion Drugs

In September 2000, after years of advocacy from Planned Parenthood and others, the FDA approved mifepristone for use as an abortion drug. In a decade, by 2010, this chemical means of induced abortion had grown to 20% of total abortions in the U.S. (Table 1, Figure 1). In another decade, by 2020, drug-induced abortions were 53% of the total, an increase of 165%. This persistent increase of abortion drug dominance over the abortion market has coincided with a series of FDA decisions regarding mifepristone which has extended its use from seven to 10 weeks gestational age, reduced the number of in-person visits required in the FDA-approved abortion drug protocol from three to one, allowed non-physicians to prescribe abortion pills, and eliminated the requirement for prescribers to report any complication except death (2016); approved a new generic form of mifepristone without requiring new safety data (2019); eliminated in-person dispensing requirements, allowing telemedicine prescribing and dispensing by mail (2021); and allowed dispensing by certified pharmacies (2023) [31]. As a result, the expansion of drug-induced abortion has continued unabated, standing at 63% as of 2023 [32].

Notable in Figure 1 is the plainly visible increase in total abortion volumes occurring around 2018 after three decades of persistent decline. Perhaps the most surprising aspect of the sudden ending of the downward trend is that it is shared by Planned Parenthood and independent providers, unlike the very different trajectories of these two provider categories exhibited prior to that point. This suggests that the surge in demand is not completely the result of Planned Parenthood efforts to relentlessly promote induced abortion, which they have consistently done for decades. Rather, this trend suggests that the abortion drug itself, along with regulatory decisions by the FDA that made the drug more accessible, is contributing to the increase in the abortion rate.

Overmedicalization/Demedicalization of Abortion

A 1995 publication that described the use of methotrexate and misoprostol as a means to terminate early pregnancy noted that drug-induced methods had tremendous potential for increasing access to abortion by shifting abortion provision out of the clinic and offering a greater degree of personal control and privacy [33]. This early, nuanced argument for demedicalization is reflective of the perspectives of earlier abortion advocates shortly after abortion was first legalized in the United States, with an eventual president of Planned Parenthood arguing that a physician serves merely as a “rubber stamp” on a woman’s decision to have an abortion [34]. However, that early articulation of demedicalization has been accelerated and expanded by the availability of abortion drugs, even as Planned Parenthood continues to promote abortion as a critical aspect of healthcare [35]. This apparent ambivalence, somewhat paradoxically, has been effectively utilized by abortion advocates to enhance demand and accessibility under varying circumstances. The strategy of “toggling” between overmedicalization and demedicalization was on display during the COVID pandemic, when abortion advocates sued various states to exempt abortion providers from pauses on elective medical procedures by arguing that abortion is essential medical care [36]. At the same time, abortion providers sued the FDA to remove a key requirement that abortion drugs be dispensed in person, arguing that no direct oversight from a doctor was necessary [37].

In this context, abortion drugs are the perfect instrument by which to enhance demand for abortion when coupled with the motivating euphemisms of autonomy, empowerment and freedom of choice. Freedom from standard aspects of healthcare such as reporting requirements, examinations, follow-up monitoring, and even freedom to withhold information about a patient’s medical history during a subsequent emergency room visit [38,39] are all effective means of supply-induced demand. Simultaneously, abortion providers still promote the notion that induced abortion is evidence-based medical care and the standard of care option for the resolution of an unwanted pregnancy [40,41]. The existing peer reviewed science, by contrast, has not identified a single condition or disease for which an induced abortion has been determined as the therapeutic standard of care [35].

Summary

After nearly three decades of decline, the number and rate of induced abortions in the United States turned upward in 2018 and have continued to increase. Since abortions are nearly always discretionary and preferential and since there is wide variation in the rates from state to state, various types of targeted supply-induced demand strategies are likely contributing to abortion incidence. In particular, we identify a primary organization (PPFA) and a specific type of abortion procedure (abortion drugs) whose conjoining interaction coincides with the abrupt upward shift in the direction of abortion incidence. Planned Parenthood Federation of America is a huge, multinational organization with origins in eugenics and population control and with a nearly exclusive focus on the provision of induced abortion. It is particularly successful in attracting private donations and is aggressively engaged in the political process related to abortion. PPFA has increased its market share of U.S. abortions from 13% to nearly 40% during a period of time when the overall number of abortions was in decline. By increasing abortions during this period, PPFA was able to prevent a larger collapse in U.S. abortion incidence. Since its approval in 2000, drug-induced abortions using mifepristone and misoprostol have increased consistently and represented 63% of total U.S. abortions in 2023. Due largely to progressively easier access following a series of FDA decisions starting in 2016, demedicalization strategies promoted by abortion providers, access to the abortion drugs via the internet, and continuing erosion in the volume and quality of abortion incidence and complication reporting, drug-induced abortion has become the most powerful vector of supply-induced demand. Despite the lack of science to support the medical necessity of elective preferential abortion, the abortion industry has nonetheless been relatively influential in promoting the conflicting ideas that abortion is both medical care and autonomous decision-making, successfully toggling the overmedicalization/demedicalization narrative to address changing circumstances, thus enabling the survival and subsequent growth of supply-induced demand for abortion in the U.S.

Conflict of Interest: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Henshaw SK. Abortion incidence and services in the United States, 1995-1996. Fam Plann Perspect 30 (1998): 263-287.

- Data Center. Guttmacher Institute. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Maddow-Zimmet I, Candace G. Despite bans, number of abortions in the United States increased in 2023. Guttmacher Institute. May 10 (2024).

- Bickerdyke I, Dolamore R, Monday I, Preston R. Supplier-induced demand for medical services. Canberra: Productivity Commission Staff Working Paper (2002): 1-13.

- Reinhardt UE. The theory of physician-induced demand: reflections after a decade. J Health Econ 4 (1985): 187-193.

- Shigeoka H, Fushimi K. Supplier-induced demand for newborn treatment: evidence from Japan. J Health Econ 35 (2014): 162-178.

- Oliver D. Needs, wants, and demands for care. BMJ 376 (2022): o173.

- Sirovich B, Gallagher PM, Wennberg DE, Fisher ES. Discretionary decision making by primary care physicians and the cost of U.S. Health care. Health Aff (Millwood) 27 (2008): 813-823.

- Gaitan E, Steupert M, Cox T. Fact Sheet: Reasons for Abortion. Charlotte Lozier Institute. May 24 (2024).

- Biggs MA, Gould H, Foster DG. Understanding why women seek abortions in the US. BMC Womens Health 13 (2013): 29.

- Finer LB, Frohwirth LF, Dauphinee LA, Singh S, Moore AM. Reasons U.S. women have abortions: quantitative and qualitative perspectives. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 37 (2005): 110-118.

- Studnicki J, Skop I. Is induced abortion evidence-based medical practice? Medical Research Archives 12 (2024).

- Ramer S, Nguyen AT, Hollier LM, Rodenhizer J, et al. Abortion Surveillance - United States, 2022. MMWR Surveill Summ 73 (2024): 1-28.

- Aiken ARA, Starling JE, Scott JG, Gomperts R. Requests for self-managed medication abortion provided using online telemedicine in 30 US states before and after the Dobbs v Jackson Women's Health Organization decision. JAMA 328 (2022): 1768-1770.

- Brander C, Nouhavandi J, Thompson TA. Online medication abortion direct-to-patient fulfillment before and after the Dobbs v Jackson decision. JAMA Netw Open 7 (2024): e2434675.

- Planned Parenthood. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Barrett WP. America’s top 100 charities. Forbes. December 10, 2024. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Benner K. Botched care and tired staff: Planned Parenthood in crisis. New York Times. February 15, (2025).

- Planned Parenthood. A force for hope: annual report 2023-2024. May 2025. Accessed May 12 (2025).

- Statement from Planned Parenthood Action Fund on presidential election results. Planned Parenthood Action Fund. November 6 (2024).

- Lewin T. Planned Parenthood president resigns. New York Times. July 22, 1995. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Kliff S, Goldmacher S. Why Leana Wen quickly lost support at Planned Parenthood. New York Times. July 17, 2019. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Patel D, Johnson CH, Krueger A, et al. Trends in HIV testing among US adults, aged 18-64 years, 2011-2017. AIDS Behav 24 (2020): 532-539.

- Planned Parenthood. Annual report 2017-2018. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Frederiksen B, Gomez I, Salganicoff A. The impact of Medicaid and Title X on Planned Parenthood. KFF. April 16, 2025. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Larrimore R. The most meaningless abortion statistic ever. Slate. May 7, 2013. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Planned Parenthood. Annual report 1999-2000 (2000).

- Fact Sheet: Community Health Centers Outnumber Planned Parenthood Facilities 15 to 1. Charlotte Lozier Institute. April 23, 2025. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Snow B, Schorr E, Poludin V. Serving the neediest at home and abroad: 1987 annual report. Planned Parenthood.

- Spitz IM, Bardin CW, Benton L, Robbins A. Early pregnancy termination with mifepristone and misoprostol in the United States. N Engl J Med 338 (1998): 1241-1247.

- Skop I. What is the truth about the Alliance for Hippocratic Medicine v. U.S. Food and Drug Administration lawsuit? Charlotte Lozier Institute. June 13, 2023. Accessed March 19 (2025).

- Jones RK, Friedrich-Karnik A. Medication abortion accounted for 63% of all US abortions in 2023, an increase from 53% in 2020. Guttmacher Institute. March 12, 2024. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Hausknecht RU. Methotrexate and misoprostol to terminate early pregnancy. N Engl J Med 333 (1995): 537-540.

- Hardin G, Lassoe JVP, Callahan et. al, Abortion and morality: the relationship between abortion and sexual freedom. In Hall RE, ed, Abortion in a changing world. Vol 2. Columbia University Press; 1970:106-111.

- White A. Abortion is essential healthcare. Planned Parenthood Great Northwest, Hawai’i, Alaska, Indiana, Kentucky. March 28, 2024. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Bayefsky MJ, Bartz D, Watson KL. Abortion during the Covid-19 Pandemic - Ensuring Access to an Essential Health Service. N Engl J Med 382 (2020): e47.

- Kaye J. The FDA is making needless COVID-19 risks a condition of abortion and miscarriage care. We’re suing. American Civil Liberties Union. May 27, 2020. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- I took abortion pills. Will a doctor be able to tell that I had an abortion? Planned Parenthood. May 6, 2024. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Talking to health care providers after a first trimester miscarriage or abortion. Innovating Education in Reproductive Health. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- American College of Obstetricians & Gynecologists. Abortion can be medically necessary. September 25, 2019. Accessed May 2 (2025).

- Watson K. Why We Should Stop Using the Term "Elective Abortion". AMA J Ethics 20 (2018): E1175-E1180.

Impact Factor: * 6.2

Impact Factor: * 6.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.33%

Acceptance Rate: 76.33%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks