Influence of Parental Rejection on Borderline Personality Disorder

Shelina Fatema Binte Shahid*,1, Muhammad Mahmudur Rahman2, Farah Deeba3

1Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology, Department of Psychiatry, Bangladesh Medical University (BMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh

2Professor, Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh.

3Former Associate Professor, Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

*Corresponding author: Shelina Fatema Binte Shahid, Associate Professor of Clinical Psychology, Department of Psychiatry, Bangladesh Medical University (BMU), Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Received: 23 June 2025; Accepted: 30 June 2025; Published: 15 July 2025

Article Information

Citation: Shelina Fatema Binte Shahid, Muhammad Mahmudur Rahman, Farah Deeba. Influence of Parental Rejection on Borderline Personality Disorder. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 8 (2025): 675-681.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a mental disorder that makes individual’s emotion, behavior and relationship unpredictable. In personality formation and development parenting experiences, particularly warmth, rejection, and overprotection have an important impact. The objective of this study was to identify the possible relationship between parental rejection and BPD of adults in the context of Bangladesh. A total 40 adults of BPD were selected from outpatient department of Psychiatry of four hospitals and one clinic of Bangladesh by purposive sampling technique. The researcher applied the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis-II (SCID-II) for BPD. A demographic questionnaire had also given to the participants. Then Adult version of Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire for Father and Mother were applied on BPD patients with their written consent. The researcher applied descriptive and correlation statistics to analyze the data using standard statistical parameters. Result revealed that 87.5% of participants faced maternal rejection and 66.5% of participants faced paternal rejection. Result also showed that 67.5% participants facedrejection from both parents and 32.5% faced rejection from at least one parent. It was found that, maternal (r = .304, p = .028) and paternal (r = .210, p = .044) rejection were positively correlated with BPD. The hostility of mother was also significantly correlated with BPD (r =0.489, p = .001). R2 = .239 indicated 23.9% of the variance in BPD severity can be explained by mother’s hostility [F (1, 38) = 11.960; p < .001]. Using of these findings, mental health service providers might aware the parents about the risk factors of BPD that could contribute as a preventive measure.

Keywords

<p>Parental rejection, Borderline Personality Disorder, Hostility of mother</p>

Article Details

Introduction

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a mental disorder that characterized by emotional dysregulation, impulsive and problematic relationships.1, 2 Common features of BPD are uncontrollable anger and depression. Other symptoms usually consist of intense fears of abandonment and irritability, for that reason others have difficulty to understand patients with BPD.2 Suicidal behavior, substance intoxication and self-harm are also common in BPD.3 BPD is common in both general and clinical population. Nationally representative, nonclinical surveys estimated that the point prevalence of BPD was 1.4 percent and the lifetime prevalence was 5.9 percent in the US general population. Study showed that BPD is more prevalent in the American than Asian populations.4 In China there were many studies in general and psychiatric populations on BPD over the last decade.5 These studies indicated the rates of BPD was 1.3% for outpatients in clinical settings.6 Conjointly the rates was7.1% for inpatients and outpatients.7BPD can damage many areas of life. It can negatively affect intimate relationships, jobs, school, social activities and self-image, resulting in repeated job changes or losses, not completing an education, multiple legal issues, conflict-filled relationships, marital stress or divorce, self-injury, such as cutting or burning, and frequent hospitalizations, involvement in abusive relationships, unplanned pregnancies, sexually transmitted infections, motor vehicle accidents and physical fights due to impulsive and risky behavior person with BPD attempted or completed suicide.8Several psychosocial factors have been identified as risk factors for the development of BPD. For instance, growing up in a dysfunctional family, parental rearing styles, and early childhood hardships have all been found to be related to the development of BPD traits.9 Parenting experiences, particularly warmth, rejection, overprotection, and discipline, have an important impact on personality formation and development.10 According to Rohner’s parental acceptance-rejection (PAR) theory, Parental rejection refers to the absence or withdrawal of warmth, affection, or love and presence of a variety of physically and psychologically hurtful behaviors by parents towards their children.11According to PAR theory there are four types of parental rejection like- Cold and unaffectionate, hostile and aggressive, indifferent and neglecting and undifferentiated rejection. Rohner and Britner reported longitudinal evidence approving that parental rejection tends everywhere to lead the development of a variety of mental health problems, such as depression and depressed affect, conduct problems and behavior problems and substance abuse.12 The results from other longitudinal studies indicated the presence of a reciprocal and bidirectional association between children’s behavioral problems and parental rejection.13In the regular clinical practice the researcher received quite a number of BPD cases in recent days, which even seems that the number of referral is at an increase. From the researcher’s clinical experience it has been found that most of the BPD patients complained about parental rejection in their childhood. But in Bangladesh, any study dealing with the possible relationship between perceived parental rejection and borderline personality disorder has yet not been reported. In that respect present study was attempted to examine whether there is any influence of parental rejection on BPD and, if so, which types of parental rejection are most closely associated with BPD?

Methodology & Materials

It was a cross sectional, descriptive study where 40 adult participants with a diagnosis of BPD were selected purposefully from outpatient psychiatric department of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib Medical University, Dhaka medical college, Sir Salimullah medical college, Prottoy medical clinic and National Institute of Mental Health of Bangladesh. The ages of the participants were 18 years to 46 years. Their educational qualifications were literate to post graduation and they were belonged to lower to upper socio-economic classes. Medically fit and patient sufferings from BPD were included in this study. BPD patients below 18 years old, medically ill, illiterate person, suffering from Bio polar disorder, schizophrenia and active drug users were excluded from this study. The participants were diagnosed case of BPD by psychiatrist following DSM-5 criteria. Firstly, the researcher applied the Structured Clinical Interview for Diagnosis-II (SCID-II) on study participants. It is a semi-structured interview for making DSM-IV Axis II: Personality Disorder diagnosis.14 SCID-II scale scores range from 0-9, with higher scores represented a greater number of symptoms present and consequently, more severe forms of BPD. Scores of 5 or above indicated a diagnosis of BPD. After applying SCID-II a demographic questionnaire was given to get the personal demographic information of the participants. Then Adult version of Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire for Father and Adult version of Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire for Mother had applied on BPD patients.15Sub-scale scores were also calculated according to the scoring manual of the PARQ and these were labeled PARQ-M/F Warmth, PARQ-M/F Hostility, PARQ-M/F Neglect and PARQ-M/F Undifferentiated Rejection, with the M/F signifying Mother and Father Forms respectively. Severity categories of the scale scores were also identified depending on total scores: 60 to 120 represent “parental love”; 121 to 139 represent “increasing rejection but not yet serious love-withdrawal (rejection)”; 140 to 149 represent “high rejection, but not more overall rejection than acceptance”; 150 and above represent “significantly more rejection than acceptance”. Before collecting data written permission had taken from the hospital and clinics as well as written consent had taken from the participants of this study. Before responding, the researcher had explained the whole process and the purpose of the study to the participants. They were assured that the data would be kept confidential and would be used only for research purpose. For doing all these things for research purpose, ethical issues were strictly maintained and ethical approval was taken first. Data were collected from April 2021 to January 2022. After completing all questionnaires on the participants, data were processed and analyzed using SPSS (Statistical Package for Social Sciences), version 24. The categorical data were presented as frequency and percentage and correlation analysis had used to see the relationship between the variables. Key variables in the study were scores from the SCID-II and total scores from the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire: Mother and Father Forms (labeled PARQ-M Total and PARQ-F Total respectively).

Result

Based on the scores of the PARQ, all participants of BPD have experienced parental rejection. Mean age of the participants was 28.2 (SD = 7.72).17.5% of participants were male and 82.5% were female. Result showed that 67.5% of participants faced rejection from both parents. The remaining 32.5% of participants experienced rejection from at least one parent (table 1).

Table 1: Number of Participants who Experienced Parental Rejection (n=40).

|

Frequency |

Percentage |

|

|

Rejection from one parent |

13 |

32.5 |

|

Rejection from both parents |

27 |

67.5 |

|

Total |

40 |

100 |

The severity of rejection faced was also high. On the PARQ-M, 87.5% of participants experienced parental rejection, from them 10% reported increasing rejection, 10% reported high rejection and 67.5% reported significantly more rejection. On the other hand, 10% of participants reported increasing rejection, 15% reported high rejection and 41.5% reported significantly more rejection on the PARQ-F, amounting to 66.5% of total participants (Table 2).

Table 2: Number of Participants Reporting the Different Severities of Parental Rejection (n=40).

|

Increasing Rejection |

High Rejection |

Significantly more Rejection |

Total |

|||||

|

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

n |

% |

|

|

PARQ-M |

4 |

10 |

4 |

10 |

27 |

67.5 |

35 |

87.5 |

|

PARQ-F |

4 |

10 |

6 |

15 |

16 |

41 |

26 |

66.5 |

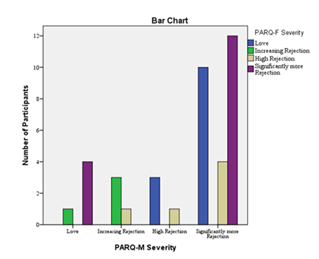

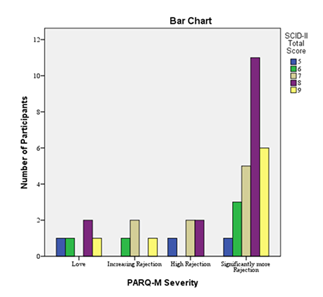

Notably, a number of participants scored in the parental love category on either PARQ-M or PARQ-F. However, all of the participants reported love from one parent faced rejection from the other parent. Data showed that 4 out of the 5 participants who scored in the parental love category on the PARQ-M scored in the highest rejection category on the PARQ-F. The remaining one scored in the increasing rejection category. Similarly, 10 out of the 13 participants who reported Parental Love on the PARQ-F experienced the highest level of rejection from their mothers. The other three faced high rejection.This relationship is visualized in figure 1. These results showed that persons diagnosed with BPD consistently faced parental rejection from at least one parent since none of the participants reported experiencing parental love from both parents. From figure 1, it could also be observed that a large number of participants 17, (43.5%) reported facing a combination of high rejection and significantly more rejection from both parents. Therefore, BPD patients often face high levels of rejection from both mother and father (Figure 1).

There was also a clear trend between BPD severity and severity of parental rejection. This trend was more visible for mother’s rejection. Participants who faced the highest levels of rejection had more severe BPD scores (figure 2).

Overall, BPD diagnosis was found to be related to parental rejection. BPD severity was more directly related to mother’s rejection than father’s rejection.Correlation analysis was performed between scale scores of PARQ-M and BPD scores. For the pair SCID-II and PARQ-M, the relationship appears to be linear with no significant outliers. Each variable was also normally distributed. Lastly, data from these instruments were meaningful when treated as interval data and have good psychometric properties. Since all the assumptions for parametric correlation were met, Pearson’s correlation coefficient was used here. Correlation was found to be significant and positive (r = .304, p = .028; table 3).

Table 3: Pearson correlation between SCID-II Total Score and PARQ-M (n=40).

|

PARQ-M Total |

||

|

SCID-II Totala |

Pearson Correlation |

.304* |

|

Sig. (1-tailed) |

0.028 |

|

|

N |

40 |

|

⋆. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed).

a. SCID score indicated BPD severity

For the pair PARQ-F Total and SCID-II Total, a linear relationship was not observed. Non-parametric correlation was used in this case since one of the key assumptions of parametric correlation was violated. Between non-parametric correlations, Kendall’s tau-b was preferred because it yields better results with small sample sizes and tied observations. Significant positive correlation was found between the two variables (τb = .210, p = .044; table 4).

Table 4: Kendall’s correlation between SCID-II Total Score and PARQ-F Total (n=40).

|

PARQ-F Total |

|||

|

Kendall's tau_b |

SCID-II Totala |

Correlation Coefficient |

.210* |

|

Sig. (1-tailed) |

0.044 |

||

⋆. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed).

a. SCID score indicates BPD severity

Relationships between SCID-II total scores and sub-scale of PARQ-M and F scores were non-linear for all sub-scales except the Hostility and undifferentiated Rejection sub-scales of the PARQ-M. The distributions of these two sub-scales also followed a normal distribution. This made it possible to use the Pearson correlation to explore their relationships with SCID-II total scores, which revealed significant positive correlations for both sub-scales of PARQ-M. The coefficients for Hostility/Aggression and Undifferentiated Rejection were 0.489 (p = .001) and 0.299 (p = .030) respectively (table 5).

Table 5: Pearson correlation between SCID-II Total and PARQ-M Hostility and PARQ-M Undifferentiated Rejection (n=40).

|

PARQ-M Hostility/ |

PARQ-M Undifferentiated Rejection |

||

|

Aggression |

|||

|

SCID-II Totala |

Pearson Correlation |

.489** |

.299* |

|

Sig. (1-tailed) |

0.001 |

0.03 |

|

|

N |

40 |

40 |

|

⋆. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (1-tailed).

⋆⋆. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (1-tailed).

a. SCID score indicates BPD severity

To determine the degree of influence of perceived parental rejection on BPD and to investigate whether parental rejection can predict BPD severity, the first regression model was constructed with PARQ-M Total scores as it was the only independent variable (since PARQ-F total did not fulfill the assumption of linearity) and SCID-II total scores was the dependent variable. This model did not yield a significant regression coefficient. Therefore, total scale scores could not reliably predict BPD severity. Next, models were attempted with sub-scale scores as predictors. The second model included PARQ-M Hostility (that indicates mother’s hostility) and PARQ-M Undifferentiated Rejection (that indicates mother’s undifferentiated rejection) using the enter method because among all the sub-scales, only these two were found to have significant correlations with SCID-II total score (which indicates BPD severities). As seen in Table 6, only PARQ-M Hostility has a significant coefficient (p < 0.01).

Table 6: Coefficients of Regression Analysis Model for PARQ-M Hostility and PARQ-M Undifferentiated Rejection with SCID-II Total Score

|

Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

||

|

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

||||

|

1 |

(Constant) |

5.488 |

0.691 |

7.947 |

0 |

|

|

PARQ-M Hostility |

0.091 |

0.029 |

0.812 |

3.153 |

0.003 |

|

|

PARQ-M Undifferentiated Rejection |

-0.065 |

0.044 |

-0.383 |

-1.49 |

0.145 |

|

|

a. Dependent Variable: SCID-II Total Score |

||||||

In this model, only PARQ-M Hostility yielded a significant regression coefficient (p < 0.01). PARQ-M Undifferentiated Rejection failed to yield a significant coefficient (p < 0.145; table 6). As a result, this model was also discarded.

The final regression model was constructed with PARQ-M Hostility (mother’s hostility) as the only independent variable and SCID-II Total Score (BPD) as the dependent variable yielded a significant coefficient (B = .055; p < 0.001). The regression equation can be written as follows: y = 5.225 + .055x, i.e., SCID-II Total Score (BPD) is increased by .055 units for unit increase in the Hostility sub-scale score of the PARQ-M (mother’s hostility). In terms of standardised coefficients, it can be stated that unit standard deviation increase in PARQ-M Hostility (mother’s hostility) causes the SCID-II Total Score (BPD) to increase by .489 standard deviation units (table 7).

Table 7: Coefficients of Regression Analysis Model for PARQ-M Hostility with SCID-II Total Score

|

Model |

Unstandardized Coefficients |

Standardized Coefficients |

t |

Sig. |

||

|

B |

Std. Error |

Beta |

||||

|

1 |

(Constant) |

5.225 |

0.678 |

7.704 |

0 |

|

|

PARQ-M Hostility |

0.055 |

0.016 |

0.489 |

3.458 |

0.001 |

|

|

a. Dependent Variable: SCID-II Total Score |

||||||

Therefore, mother’s hostility is a significant predictor of BPD severity. The R2 value (.239; table 8) indicates that 23.9% of the variance in BPD severity can be explained by mother’s hostility [F (1, 38) = 11.960; p < .001; table 9]. The R2 value was used instead of the adjusted R2 because the adjusted R2 tests multiple independent variables against the regression model. This was not necessary here because only one independent variable was used in the model.

Table 8: Summary of Regression Analysis Model for PARQ-M Hostility with SCID-II Total Score

|

Model |

R |

R Square |

Adjusted R Square |

Std. Error of the Estimate |

|

1 |

.489a |

0.239 |

0.219 |

1.04 |

|

a. Predictors: (Constant), PARQ-M Hostility |

||||

Table 9: ANOVA of Regression Model for PARQ-M Hostility with SCID-II Total Score

|

Model |

Sum of Squares |

df |

Mean Square |

F |

Sig. |

|

|

1 |

Regression |

12.927 |

1 |

12.927 |

11.96 |

.001b |

|

Residual |

41.073 |

38 |

1.081 |

|||

|

Total |

54 |

39 |

||||

|

a. Dependent Variable: SCID-II Total Score |

||||||

|

b. Predictors: (Constant), PARQ-M Hostility |

||||||

The ANOVA of regression model is considered statistically significant at 1% level [F (1, 38) = 11.960; p < .001; table 9].

Discussion

Present study revealed that all participants of BPD had experienced parental rejection. This study expressed that 87.5% of participants experienced maternal rejection and 66.5% of participants experienced paternal rejection. Rest of the participants who reported love from one parent faced high level of rejection from another parent. So overall, BPD features was found to be associated to parental rejection. This finding was alike to other findings. One Chinese study revealed that parental rejection, punishment, control and rearing pattern have contributed to development of BPD.16Other studies revealed the similar result, systematically reviewed 51 case-control and cohort studies examined psychosocial vulnerability factors for BPD that identified and classified five vulnerabilities factors for the etiology of BPD, two of which related to childhood trauma and “unfavorable” parenting (e.g. unfavorable parenting involved abuse and rejection from parents).17Mean age of the participants of present study was 28.2 (SD = 7.72). Previous researcher identified in their study that the mean age of the borderline group was younger (mean age 24.44 years), 18 which was close to the finding of this study. In this study it was found that 17.5% of participants were male and 82.5% were female that indicated BPD was more common in female than men in recent year. According to American Psychological Association, in both clinical and forensic populations significantly higher rates of BPD were constantly observed among females as compared to males 19 Present findings were supported by previous studies where BPD was significantly high in female than male.20,21 Other researchers found that women are overly represented in clinical settings including up to 75% of BPD diagnosis.21Result of the present study showed that 67.5% of participants faced rejection from both parents. The remaining 32.5% of participants experienced rejection from at least one parent. One study showed that before the age of 18 up to 84% of individual with BPD experienced neglect and emotional abuse from both parents.22Present study revealed that BPD severity was more directly related to mother’s rejection (r = .304, p = 028) than father’s rejection (τb = .210, p = .044). Similar result was found in a study which presented that adolescents with BPD features were raised by those mother who gave lack of warm and affection, more overprotection, and more rejection than healthy controls.23Another study showed that insecure attachment and lack of caring from one’s mother were associated with Borderline features.24But one research on “Perceived parental rejection, psychological maladjustment and borderline personality disorder”- indicated that people with BPD perceived more paternal rejection than maternal rejection, and scored significantly high on the psychological maladjustment.25 This findings opposed the present findings. It might be for the cultural difference. In our culture offspring usually expected warmth, affection and care more from mother than their father. They expected that mother would be more affectionate and accepted that father would be busy with their outside work and would not be much responsible to give care and warmth. That’s why mother’s rejection might impact more than father’s rejection to predict BPD. Present study found that there was a significant correlation between maternal hostility and severity of BPD. The coefficients for hostility/aggression of mother was 0.489 (p = .001). Therefore, it was revealed that mother’s hostility/aggression was a significant predictor of BPD severity. In a cross-sectional study, it was found that maternal hostility was associated with BPD symptoms in offspring age 15.26which was similar to the present study.

Conclusion

This study indicated that there was an association between parental rejection and BPD. The severity of BPD was positively correlated with maternal rejection than paternal rejection. There was also a strong relationship between maternal hostility and severity of BPD. It is known that to treat BPD is too difficult and outcome of treatment of BPD is not satisfactory. So, the researcher felt that interventions should be developed at preventative nature as BPD was more likely associated with parenting issues. Thus, the researcher assumed that using the findings of this research would be helpful to make aware the parents about the behavioral features which made the offspring vulnerable to develop BPD. Therefore, this research has suggested to do further research in a large scale so that mental health professional could create an appropriate parenting style for the child and could educate the parents that might contribute to prevent BPD.

Funding: No funding sources

Conflict of interest: This research is a part of Ph. D study (awarded on 8 May, 2023) of first author Dr. Shelina Fatema Binte Shahid from Department of Clinical Psychology, University of Dhaka.

Ethical approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee.

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical manual of mental disorder. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing (2013).

- Gunderson JG. Revising the borderline diagnosis for DSM-V: An alternative proposal. Journalof Personality Disorders 24 (2010): 694–708.

- Manning S. Loving Someone with Borderline Personality Disorder. The Guilford Press (2011).

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence, Correlates, Disability, and Comorbidity of DSM-IV Borderline Personality Disorder: Results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 69 (2008): 533-45.

- Zhong J, Leung F. Diagnosis of borderline personality disorder in China: Current status and future directions. Curr Psychiat Rep 11 (2009): 69-73.

- Xiao Z, Yan H, Wang Z. Trauma and dissociation in China. Am J Psychiat 163 (2006): 1388-91.

- Yang J, McCrae RR, Costa The cross-cultural generalizability of Axis-II constructs: an evaluation of two personality disorder assessment instruments in the People's Republic of China. J Pers Disord 14 (2000): 249-63.

- Palmer BA. Mayo Clinic, Rochester, © 1998-2015 Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. All rights reserved (2015).

- Paris J. Personality disorders over time. Precursors, course, and outcome. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing (2003).

- Rohner RP. The warmth dimension: Foundations of parental acceptance-rejection theory. Inc: Rohner Research. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage Publications (1986).

- Rohner RP, Khaleque A, Cournoyer DE. Parental acceptance-rejection theory, methods, evidence, and implications. In: Rohner RP, Khaleque A. editors. Handbook for the study of parental acceptance and rejection. Storrs, CT 06268, USA: Rohner Research Publications (2005):1-25.

- Rohner RP, Britner PA. Worldwide mental health correlates of parental acceptance rejection: Review of cross-cultural and intracultural evidence. Cross-Cultural Research 36 (2002): 16-47.

- Cohen P, Brook JS. The reciprocal influence of punishment and child behavior disorder. In: McCord J, editor. Coercion and punishment in long-term perspectives. New York: Cambridge University Press 64 (1995): 154-64.

- First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JB, Benjamin LS. Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II: Personality Disorders, (SCID-II). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press (1997).

- Jasmine UH, Uddin MK, Sultana S. Adaptation of the Parental Acceptance-Rejection Questionnaire and Personality Assessment Questionnaire in Bangla Language. Bangladesh Psychological Studies 17 (2007): 49-70.

- Jianjun H. Childhood experiences of parental rearing patterns reported by Chinese patients with borderline personality disorder. International Journal of Psychology 49 (2014): 38-45.

- Keinänen MT, Johnson JG, Richards ES, Courtney EA. A systematic review of the evidence-based psychosocial risk factors for understanding of borderline personality disorder. Psychoanalytic Psychotherapy 26 (2012): 65–91.

- Gupta S, Mattoo SK. Personality disorders: Prevalence and demography at a psychiatric outpatient in North India. Intern. J. Soc. Psychiatry (2012): 58146–152.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Text revision. Washington DC: Author (2000).

- Sansone RA, Sansone LA. Borderline personality and criminality. Psychiatry 6 (2009): 16–20.

- Skodol AE, Bender DS. Why women are diagnosed borderline more than men? Psychiatric Quarterly 74 (2003): 349–60.

- Zanarini MC, Yong L, Frankenburg FR, Hennen J, Reich DB, Marino MF, et al. Severity of reported childhood sexual abuse and its relationship to severity of borderline psychopathology and psychosocial impairment among borderline inpatients. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 190 (2002): 381–87.

- Ougrin D, Tranah T, Leigh E, Taylor L. Rosenbaum Asarnow J. Practitioner review: self-harm in adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 53 (2012): 337–50.

- Angela D, Nickell, Carol J, et al. Attachment, Parental Bonding and Borderline Personality Disorder Features in Young Adults. Journal of Personality Disorders 16 (2002): 148-59.

- Ronald P, Rohner, Sherri A, Brothers MA. Perceived Parental Rejection, Psychological Maladjustment, and Borderline Personality Disorder. Journal of Emotional Abuse 1 (2008): 81-95.

- Herr NR, Hammen C, Brennan PA. Maternal borderline personality disorder symptoms and adolescent psychosocial functioning. Journal of Personality Disorders 22 (2008): 451–65.

Impact Factor: * 6.2

Impact Factor: * 6.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.33%

Acceptance Rate: 76.33%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks