Novel Tetrazolo-Pyridazine-Based MACC1 Transcriptional Inhibitor Reduces NFκb Signaling Pathway as Key Antimetastatic Mechanism of Action

Paul Curtis Schöpe1, Mathias Dahlmann1,2, Dennis Kobelt1,2, Bjoern-O Gohlke3, Abdelrhman M Shoman1,4, Wolfgang Walther1, Robert Preissner3, Marc Nazaré5, Ulrike Stein1,2*

1 Experimental and Clinical Research Center, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and MaxDelbrück-Center for Molecular Medicine, Robert-Rössle-Str. 10, 13125 Berlin, Germany

2 German Cancer Consortium (DKTK Partnersite Berlin), Deutsches Krebsforschungszentrum (DKFZ), Im Neuenheimer Feld 280, 69120 Heidelberg, Germany

3 Institute of Physiology and Science-IT, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, Charitéplatz 1, 10117 Berlin, Germany

4 Molecular Pharmacology Research group, Department of Pharmacology, Toxicology and Clinical Pharmacy, Faculty of Pharmacy and Biotechnology, German University in Cairo, Cairo 11835, Egypt

5 Leibniz-Forschungsinstitut für Molekulare Pharmakologie, FMP, Robert-Rössle-Str. 10, 13125 Berlin, Germany

* Corresponding authors: Ulrike Stein, Experimental and Clinical Research Center, Charité – Universitätsmedizin Berlin, and MaxDelbrück-Center for Molecular Medicine, Robert-Rössle-Str. 10, 13125 Berlin, Germany.

Received: 13 November 2025; Accepted: 17 November 2025; Published: 30 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Paul Curtis Schöpe, Mathias Dahlmann, Dennis Kobelt, Bjoern-O Gohlke, Abdelrhman M Shoman, Wolfgang Walther, Robert Preissner, Marc Nazaré, Ulrike Stein. Novel Tetrazolo-Pyridazine- Based MACC1 Transcriptional Inhibitor Reduces Nfκb Signaling Pathway as Key Antimetastatic Mechanism of Action. Journal of Biotechnology and Biomedicine. 8 (2025): 356-369.

DOI: 10.26502/jbb.2642-91280203

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Targeted therapies for patients at high risk of metastasis are crucial to improving treatment outcomes and survival. Metastasis Associated in Colon Cancer 1 (MACC1) has emerged as a key molecule driving metastasis and serves as a prognostic and predictive biomarker for therapy response. Elevated MACC1 expression correlates with poor survival and resistance to standard chemotherapeutics. Recently, we identified a novel tetrazolo-pyridazine-based transcriptional inhibitor of the MACC1 gene through a high-throughput screen using the human MACC1 promoter linked to a luciferase reporter. While the initial phenotypic screening confirmed MACC1 inhibition, the molecular target and affected signaling pathways remained unknown, prompting further investigation. RNA sequencing revealed that treatment with Compound 22 attenuates TNF-α signaling via the NFκB pathway. Gene ontology analysis of differentially expressed genes indicated alterations in cell cycle regulation and intermediate filament-based processes, resulting in reduced proliferation and enhanced epithelial characteristics. Molecular analyses demonstrated decreased NFκB p65 and p50 activity, reduced nuclear translocation, and diminished activity on the MACC1 promoter. In silico predictions identified p105 as a potential protein target, and experimental validation showed that Compound 22 blocks TNF-α-induced phosphorylation of p105. Although additional studies are required to confirm direct binding to p105, our data suggest that this tetrazolo-pyridazine-based compound effectively suppresses NFκB signaling, leading to reduced MACC1 expression. Consequently, inhibition of this pathway and it subsequent targets such as MACC1 reduces the metastatic potential of cancer cells, highlighting a promising therapeutic strategy for metastasis prevention.

Keywords

<p>MACC1; Tetrazolo-pyridazine-based compounds; Mode of Action; Transcriptomics; Targeted therapy; Metastasis</p>

Article Details

Introduction

The most lethal attribute of cancer is still the spread of metastasis into peripheral organs, creating a high burden for patients [1]. Depending on the cancer entity, metastasis make up to 70-90% of cancer deaths [2]. Novel approaches to target metastasis inducing genes such as Metastasis Associated in Colon Cancer 1 (MACC1) are crucial to improve patient survival and cancer therapy outcome in metastatic patients. Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most lethal cancer entities in both sexes worldwide [3]. The development of metastasis represents a strong barrier in cancer therapy leading to lower survival rates and reduced therapy outcome of patients. According to the National Cancer Institute of the United States and their cancer statistic facts for CRC, the 5- year survival rate for localized CRC is 91.5% and drops to 74.6% for regional and 16.2% for distantly metastasized CRC [4]. These statistics highlight the need to further improve cancer therapies by developing novel targeted therapies for patients with the least favorable outcome due to up-regulation of key metastatic driver genes such as MACC1.

MACC1 is a tumor stage-independent prognostic biomarker for metastasis. Patients with a high expression of MACC1 in their primary tumor are highly likely to form metachronous metastasis or are already synchronously metastasized. Moreover, MACC1 promotes many of the cancer hallmarks, ultimately leading to an invasive phenotype and metastasis formation [5]. By now the value of MACC1 has been shown in a multitude of publications, meta-analysis and many different solid cancer entities [6]. This exemplifies the importance of developing novel intervention strategies targeting this metastatic gene. Through shRNA or knockout experiments, we showed that targeting MACC1 and lowering its expression levels reduces migratory properties in cells and metastasis formation in mice [7]. The discovery of tetrazolo-pyridazine-based compounds for MACC1 transcriptional inhibition was an important step to extend the tool box of novel targeted anti-metastatic therapies [8]. This compound was identified by executing a phenotype-based high-throughput screen (HTS). This HTS was conducted using HCT116 cells stably transfected with a reporter construct consisting of the human MACC1 promoter coupled to a luciferase reporter gene. By using this reporter construct, MACC1 transcriptional inhibitors can be found. However, this approach does not directly establish the mode of action (MoA) or protein target of the identified substance, leaving these aspects open for further investigation. Therefore, a detailed analysis of the molecular action of the substance is necessary to further optimize its action and increase the chance to predict off-target effects, ultimately aiding the successful implementation into clinical trials. In the discovery paper of Compound 22, a first hypothesis [8] on the MoA of Compound 22 was presented. Searching for other tetrazolo-pyridazine-harboring compounds revealed Ro106-9920 [9], a potent NFĸB inhibitor. It is known that MACC1 is a target gene of the NFĸB signaling pathway. Its gene expression can be elevated by TNF-α stimulation of the NFĸB signaling pathway [10]. The analysis of the regulation of the MACC1 gene expression showed, that Compound 22 blocks the induction of MACC1 by TNF-α. Furthermore, we predicted p65 and p50 transcription factor (TF) binding sites within the MACC1 promoter [8].

The aim of this study was to elucidate the molecular pathway by which Compound 22 leads to a reduction of the MACC1 gene expression.

We report our efforts to deconvolute the MoA of Compound 22 using RNA-sequencing to reveal gene expression changes under Compound 22 with subsequent analysis to establish an attenuated signaling pathway. Further, the molecular effects of Compound 22 on the attenuated signaling pathway were tested. A target prediction using the chemical scaffold of Compound 22 and subsequent integration of the differentially expressed gene (DEG) list revealed a member of the NFĸB signaling pathway as possible protein target which was investigated for the binding of Compound 22 through in silico and CETSA experiments.

In conclusion, we revealed that the NFĸB signaling pathway is attenuated by Compound 22 and the molecular as well as functional consequences of it. Moreover, a possible protein target was established through which Compound 22 facilitates its action.

Material and Methods

Cell lines and cultivation

Human CRC cell lines HCT116 and SW620 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. Both cell lines were cultivated in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc, Waltham, MA, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (vol/vol; FBS; Capricorn Scientific, Ebersdorfergrund, Germany) in a humidified incubator at 37°C with 5% CO2. The MycoAlert mycoplasma detection kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) was used regularly to test for mycoplasma contamination.

Compounds and treatments

Compound 22 was purchased from Enamine (Kyiv, Ukraine) and Ro106-9920 from Medchemexpress (Princeton, NJ, USA). All compounds were purchased as powder, to solubilize in DMSO with a stock concentration of 10 mM and aliquoted. Storage took place at -70°C. DMSO was used as a negative control in all experiments and the DMSO concentration was always adjusted to the compound concentration in all treatment setups. Lyophilized human TNF-α (Peprotech, Cranbury NJ, USA) was reconstituted according to the manufacturer’s recommendation in water using 0.1% BSA as a carrier protein.

Quantitative reverse transcription - polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR)

For the analysis of mRNA expression, cells were seeded into 24-well plates (1 × 105 cells/well; in 500 μL DMEM). Following a 24 h incubation period, the cell medium was aspirated, and 500 µL of compound solution was added to each well. After another 24 h incubation period, total RNA was extracted using the Universal RNA Kit (Roboklon, Berlin, Germany) and quantified using a Nanodrop (Peqlab, Erlangen, Germany). Next, 25 ng RNA were used to reverse transcribe into cDNA using the cDNA Synthesis Kit (Biozym, Hessisch Oldendorf, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s protocols in volumes of 10 µL. All cDNA was stored at 4°C for immediate or at -20°C for later use. After reverse transcription, cDNA was diluted 1:3 with water, qRT-PCR was performed using 2 µL of cDNA with the Blue S’Green qPCR Mix (Biozym). Amplification reaction occurred in a PCR 96-well TW-MT-plate using the LightCycler 480 II (Roche, Basel, Switzerland), according to the manufacturer’s recommendations in a volume of 10 µL. Data analyses were performed with the software of LightCycler 480 SW 1.5.1.62 (Roche). All samples were run in technical triplicates and the corresponding mean values were calculated. Each mean value of the cDNA was normalized to the respective mean value of the DMSO control.

|

Name |

Sequence Forward |

Sequence Reverse |

|

BCL3 |

GAACACCGAGTGCCAAGAAACC |

GCTAAGGCTGTTGTTTTCCACGG |

|

NFKBIA |

AGGAGTACGAGCAAATGG |

CAGGCAAGATGTAGAGGG |

|

Myc |

CCTGGTGCTCCATGAGGAGAC |

CAGACTCTGACCTTTTGCCAGG |

|

TNFAIP3 |

TCCTGCCTTGACCAGGACTTG |

CATTGTGCTCTCCAACACCTCT |

|

MACC1 |

TTC TTT TGA TTC CTC CGG TG |

ACTCTGATGGGCATGTGCTG |

|

NFKB1 |

GCAGCACTACTTCTTGACCACC |

TCTGCTCCTGAGCATTGACGTC |

|

RelA |

AAATGCCATGCAGAATGCCC |

TGTCACAGGTTCCTCAACTCT |

Table 1: qPCR primer for qPCR.

Western blotting (WB)

Cells were seeded into 6-well plates (5 × 105 cells/well; in 2 mL DMEM/well) for protein expression or phosphorylation analysis. Following a 24 h incubation period, the cell media were aspirated, and 2 mL of the prepared compound solution was added to each well. After the respective treatment durations, the cells were washed with PBS, detached via scraping and pelleted at 1000 × g for 5 min. Lysis of the cell pellet was followed by dissolving them in 50 µL of RIPA buffer (composed of 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40), supplemented with complete protease inhibitor tablets (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and for phosphorylated proteins phosphatase inhibitor tablets were added additionally (Roche). For protein extraction, samples were incubated on ice for 30 min, whilst vortexing the samples every 10 min. Lysates were centrifuged at 14,800 × g for 30 min at 4°C, after which the protein-containing supernatant was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube and stored at -20°C. The Pierce TM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) was used to determine the protein concentration to prepare SDS loading samples containing 10 or 20 ng of protein depending on the application. For whole cell lysates and the cytosolic fraction 10 ng and for the nuclear fraction 20 ng were used. The SDS loading samples contained 100 mM DTT, 1 × NuPage™ LDS sample buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), and PBS to a total volume of 20 μL. All samples were heated for 10 min at 95°C before being loaded into the SDS gels (acrylamide content: separation gel 15%, stacking gel 5%), stacked at 70 V for 30 min and separated at 120 V for 90 min. A broad range protein ladder (Spectra Multicolor, Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.) was used to indicate the molecular weight of the proteins. After conducting the SDS-PAGE, proteins were transferred with a methanol-activated PVDF membrane (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) via semi-dry electro blotting employing Bio-Rad’s blotting system (25 V and 1.3 A were applied for a duration of 7 min). After the blotting, PVDF membranes were blocked for 1 h with a TBS-T solution (10 mM Tris-HCl; pH 8, 0.1% Tween 20 and 150 mM NaCl) harboring 5% BSA. Membranes were cut into sections containing the respective protein bands and incubated separately with their respective antibody solutions (Table 2) overnight on a shaker at 4°C. The next day, membranes were washed 8 times for 5 min with TBS-T and then incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (for rabbit-based AB: mouse anti-rabbit IgG antibody 1:10,000 dilution (Promega, Madison, WI, USA), for the mouse-based AB: goat anti-mouse IgG antibody 1:20,000 dilution (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA)) for 1 h at room temperature. After the incubation, the membranes were washed 12 times, each for 5 min with TBS-T. Then the Western Bright ECL substrate (Biozym) was added to the membranes and incubated for at least 30 sec. Subsequently Xray films (Kisker Biotech, Steinfurt, Germany) were exposed to the membranes. All Western blots were repeated independently three times for each experiment and condition. Quantification was conducted using Image J version 1.54g.

|

Name |

Dilution |

Host |

Manufacturer |

|

Anti-human ß-actin |

1:20,000 |

Mouse |

Sigma-Aldrich |

|

Anti-human p105/p50 |

1:10,000 |

Rabbit |

Cell Signaling Technology |

|

Anti-human p-p105 |

1:10,000 |

Rabbit |

Cell Signaling Technology |

|

Anti-human p65 |

1:10,000 |

Rabbit |

Active motif |

|

Anti-human ß-tubulin |

1:10,000 |

Mouse |

BD Pharmingen |

|

Anti-human Histone 4 |

1:10,000 |

Rabbit |

Active motif |

|

Normal Rabbit IgG (ChIP) |

1:10,000 |

Rabbit |

Cell Signaling Technology |

|

Mouse anti-rabbit, HRP Conjugate (WB) |

1:10,000 |

Mouse |

Promega |

|

Goat anti-mouse |

1:20,000 |

Goat |

Invitrogen |

Table 2: Antibody dilutions for WB, all antibody dilutions were prepared in TBS-T supplemented with 5% of BSA.

RNA-sequencing

1 × 105 HCT116 cells/well were seeded into 24 well plates. After 24h incubation period, the cell media was aspirated and 0.5 mL cell media with 10 µM Compound 22 or DMSO as negative control was added to each well. Following 24 h of incubation period, the medium was aspirated and total RNA was extracted using the Universal RNA kit (Roboklon). The RNA concentration was measured using a Nanodrop (Peqlab). An aliquot of each sample was used for quality control using a qRT-PCR assay to determine the reduction in MACC1 gene expression. After confirmation of the MACC1 reduction, an aliquot of each sample was processed and sequenced at the Genomics facility of the Max Delbrück Center (MDC). An mRNA Truseq library prep was done and one SP Flowcell PE100 was used in a Novaseq 6000 machine (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) to sequence 60 million read per sample. FastQC was done and the raw data was handed over and analyzed independent of the Genomics facility of the MDC.

Analysis of RNA-sequencing data using internal galaxy server

The processing and analysis of the raw data received from the Genomics facility was conducted on the Galaxy server of the MDC and the European Galaxy server. The tutorial of the Galaxy Training webpage: Reference-based RNA-Seq data analysis was used [11-13]. In brief, for quality control the Flatten collection Galaxy version 1.0.0, FastQC Galaxy version 0.73 + galaxy 0 and MultiQC Galaxy version 1.9 + galaxy 1 were used. The trimming was conducted with Cutadapt Galaxy version 3.4 + galaxy 2. Mapping was done with RNA STAR Galaxy version 2.7.8a + galaxy 0 and the human reference genome release 44 (GrCh38.p14, regions: ALL) as a GFF3 file. Strandness was estimated using the RNA STAR output and RNA STAR was then further used to count reads per gene following the tutorial. For the analysis of the differential gene expression, DESeq2 Galaxy version 2.11.40.6 + galaxy 2 was used. The annotation of the DESeq2 results was conducted with the tool Annotate DESeq2/DEXSeq output tables Galaxy version 1.1.0. This resulted in a list of differentially expressed genes which was then further used for subsequent analysis such as the gene set enrichment analysis. The DEG list of Compound 22 vs DMSO used in this study is available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Gene Ontology analysis and Gene set enrichment analysis

Gene ontology analysis was conducted with genes of the differentially expressed gene list which had a log2(fold change) of at least 1 or -1. Upregulated and down regulated genes were inserted separately into the online tool GO Enrichment Analysis release 16.03.2025 of the Gene Ontology Resource (https://www.geneontology.org/) [14]. The gene set enrichment analysis was performed using the GSEA software version 4.3.3 from the broad institute (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/index.jsp). The differentially expressed gene list was adjusted to the GSEA input format and the hallmark gene set 15 was downloaded from the broad institute webpage. DMSO vs Compound 22 was run against the hallmark gene set using 1000 permutations, permutation type as “phenotype” and “No_Collapse” for remapping of gene symbols.

Kinase screen

A kinase screen was conducted at Eurofins (KinaseProfiler) using the Full Human Panel (10 µM ATP) kinase Profiler. Compound 22 was provided in a powdered form and 10 µM concentration was used for the screening which was conducted in duplicates. Staurosporine or specific inhibitors of the respective kinase was used as a positive control to define 0% kinase activity and DMSO was used as negative control to define 100% kinase activity. The assay works through radiometric labeling of phosphate of ATP and is a direct measurement of the catalytic activity of the kinases. The activity after treatment was displayed in % and was then converted by subtracting it from 100 to arrive at the % of inhibition for each kinase.

ELISA assays

The TransAM NF-ĸB Family Kit was purchased from Active Motif (Carlsbad, CA, USA) to evaluate the activity of p50 and p65 after treatment with Compound 22. On day 0, 0.5 × 106 cells were seeded into 6 well plates. After 24 h of incubation, the wells were treated with either DMSO as negative control or 10 µM of Compound 22 in duplicates for 1 h. After the incubation, 100 ng/mL TNF-α was added to one of the duplicates and incubated for 90 min. Cells were scraped of the plate, centrifuged at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 5 min and then the supernatant was removed. The cell pellet was resuspended and lysed in 50 µL of the complete lysis buffer provided by the kit and proteins were extracted by incubation on ice for 30 min, whilst vortexing every 10 min. Cell lysate was centrifuged at 14,800 × g for 30 min at 4°C and the supernatant was transferred to a new microcentrifuge tube. Extracted protein were either stored on ice for immediate readout or frozen at -70°C until the next day. The next day the protein concentration was measured using the Pierce TM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.). 80 µg protein were diluted into 40 µL of complete lysis buffer. The protocol of the manufacturer was followed and the read out was done using the Infinite plate reader (Infinite Series 2000, Tecan, Männedorf, Switzerland) according to the manufacturers protocol. Measurements were normalized to the DMSO control.

Chromatin Immunoprecipitation assay (ChIP)

For chromatin immunoprecipitation assay the EZ ChIP kit from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) was purchased. On day 0, 2.5 × 106 cells were seeded into 150 mm petri dishes (20 mL medium) and incubated for 2 days until a confluency of 80-90% was achieved. Then, the cells were pretreated with Compound 22 (10 µM) or DMSO as negative control for 3 h. After that 1 dish of each treatment was treated with 100 ng/mL TNF-α for 15 min. Following the incubation period, the cells were fixated with 1% formaldehyde and the protocol provided by the manufacturer was followed. Sonication took place on wet ice using a sonicator (Bandelin electronics, Berlin, Germany) at 50% power with 40 cycles for 25 pulses with 30 sec cooling time after every 5 pulses. Preclearing of the lysate was done using 60 µL of the agarose beads provided by the kit for 1 h at 4°C under rotation. Then the protein fixed to chromatin were incubated using 2 µg of rabbit IgG (BD Pharmingen, San Diego, CA, USA) or 4 µL of p65 antibody (Active Motif) or control antibodies of the kit overnight at 4°C under rotation. Capturing of the antibody-protein complexes was done using 50 µL of Dynabeads protein G (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4°C. Washing was conducted as described by the kit protocol. Elution took place according to the protocol provided by the dynabeads by the elution buffer consisting of 50 mM glycine at pH 2.5. Reversing of cross links and the extraction of DNA were completed as described in the assay protocol. To measure the DNA a qPCR was conducted as described in the assay protocol using RelA specific primers (Table 1).

Cellular fractionation experiments

To evaluate the spatial distribution of TFs p65 and p50 under Compound 22 treatment, the Nuclear Extract kit from Active Motif was purchased. On day 0, 2 × 106 cells were seeded into 100 mm petri dishes. After 24 h of incubation time, the cells were pretreated with 10 µM Compound 22 or the DMSO negative control for 3 h. After the incubation time one flask of each condition was treated with 100 ng/mL TNF-α for 15 min. The protocol of the manufacturer was followed. In brief, cells were washed once with PBS and phosphatase inhibitor. Using 3 mL of PBS and phosphatase inhibitor, the cells were scraped off the plate and transferred to a centrifuge tube and centrifuged at 200 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Supernatant was thrown away and cells were then resuspended in 1 mL of hypotonic buffer for 20 min. After adding detergent and vortexing at maximum setting for 15 sec, the cell lysate was centrifuged for 1 min at 14,000 × g. The supernatant (cytosol fraction) was transferred into new pre-chilled microcentrifuge tubes. The remaining nuclear pellet was washed 3 times with PBS and then resuspended in 50 µL complete lysis buffer and sonicated at 50% power for 2 pulses with 40 cycles and incubated on ice for 30 min on a rocking platform set at 150 rpm. Then the nuclear lysate was vortexed for 30 sec at the highest setting and centrifuged for 10 min at 14,000 × g. The supernatant (nuclear fraction) was then transferred to a pre-chilled microcentrifuge. Both, the cytosol and nuclear fraction were stored at -70°C until use for Western blotting (see section 2.4). Quantification was conducted with ImageJ version 1.54g.

Drug target prediction

To identify potential biological targets of small molecules, a target prediction approach was employed using logistic regression models trained on extended-connectivity fingerprints (specifically, 2048-bit Morgan fingerprints). These models capture the topological features of chemical compounds and provide a vectorized representation suitable for machine learning-based classification. To ensure the generalizability and robustness of the predictive models, their performance was assessed using stratified 10-fold cross-validation during the training phase.

For each compound-target pair, the prediction system outputs two key metrics: predicted probability and model accuracy. The predicted probability reflects the likelihood that a given compound interacts with a particular protein target, as estimated by the learned decision boundary of the logistic regression model. This value can be interpreted as the model’s degree of confidence in a true positive interaction.

Complementing this, the model accuracy provides a target-specific performance indicator, derived from cross-validation on the training set. It represents the overall fraction of correctly classified cases during model training and varies considerably between different targets, depending on the available data, class distribution, and chemical diversity. Therefore, this value serves as a crucial measure of the reliability and interpretability of individual predictions.

To avoid over-interpretation of unreliable predictions, predictions from models with a cross-validated accuracy below 0.7 were considered insufficiently robust and should be interpreted with caution or disregarded entirely in downstream analyses. This cut-off was chosen to ensure a minimum level of confidence in the underlying model’s generalization ability.

Together, the probability score and model accuracy enable a nuanced assessment of predicted compound-target interactions by combining quantitative confidence for individual predictions with an overall measure of model quality.

CETSA - cellular thermal shift assay

The protocol was adapted from Jafari et al. [16]. For this 3 × 107 were seeded into T75 flasks and immediately treated with 10 µM of Compound 22 or solvent control. After 1 h of incubation, the cells which attached to the flask were detached by scratching, centrifuged and washed once with PBS and centrifuged to pellet the cells. Then the cells were resuspended in 1 mL of PBS supplemented with proteinase inhibitor. 100 µL (3 × 106 cells) were distributed into 9 PCR tubes and heated for 3 min over a temperature gradient from 46-54°C (46.1, 47.1, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 52.9, 53.9°C) with subsequent cool down of 3 min at 25°C. The tubes were then immediately snap frozen using liquid nitrogen and stored at -70°C until the next days when the protocol was continued. The snap freezing was repeated 2 times to ensure proper cell lysis with thawing them by room temperature and short vortexing in between freezing. After completion of lysis, the cells were centrifuged for 10 min at 20,000 × g at 4°C to separate in soluble proteins and cell debris from the protein lysate. The lysate was then used to conduct an SDS-PAGE with subsequent Western blotting. The membranes were blocked for 60 min with 5% BSA dissolved in TBS-T buffer and then incubated over night with p105 and ß-actin antibody (concentrations are displayed in table 2). Washing, second incubation and exposure were done as described in 2.4. Western blot bands were quantified using ImageJ version 1.54g to reveal a potential thermal shift compared to the solvent and inactive analogue.

Molecular docking

A search in the Protein Data Bank (PDB) for the structure of the death domain in the human nuclear factor NF-κB p105 subunit yielded one crystal structure for p105 (p105 bound covalently to an inhibitor) and one solution NMR structure for the Death domain in human Nuclear factor NF-kappa-B p105 subunit. The solution NMR structure of the death domain (PDB ID: 2DBF) was selected for further evaluation. Small molecule preparation for docking was performed using Molecular Operating Environment (MOE) 2019. The preparation protocol included hydrogen addition, ionization state normalization, and generation of three-dimensional coordinates. Energy minimization was subsequently applied using the molecular preparation module in the MOE database to generate low-energy conformers. Molecular docking studies were conducted using the GOLD suite version 5.1 with the ChemPLP scoring function. The binding site was determined based on the death domain sequence and neighboring amino acid residues, with the putative binding site identified using the MOE Site Finder tool.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0.2 (GraphPad Software Inc, La Jolla, CA, USA). For comparison of the control group (DMSO) with multiple experimental groups, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Dunnett’s post-hoc-test or Tukey post-test was performed. Moreover, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was conducted for Gaussian distribution confirmation. P values below 0.05 were considered as statistically significant (level of significance * = p < 0.05, ** = p < 0.01, *** = p < 0.001)

Results

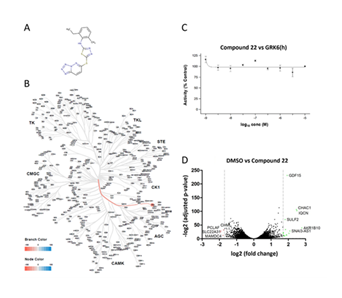

Kinase screen demonstrates Compound 22 is not a kinase inhibitor

As a first step in the deconvolution of the MoA of Compound 22, a kinase screen was conducted at Eurofins to evaluate whether Compound 22 is a kinase inhibitor. Its chemical structure is displayed in Figure 1A. Compound 22 was added at a concentration of 10 µM to recombinant proteins of 413 wildtype or mutated kinases (Table S1). The substrate ATP was radiometrically labeled to directly measure the catalytic activity of each kinase under compound treatment. Only a single Kinase called G protein-coupled receptor kinase 6 (GRK6) was inhibited by more than 30% (51%) by Compound 22 (Figure 1B). This was denoted as a partial hit (>50%). A full hit within the pipeline was categorized by an inhibition of at least 70% of the catalytic activity by Eurofins. An IC50 curve for GRK6 with increasing concentrations of Compound 22 was created. Here, it was shown that Compound 22 does not inhibit GRK6 as no reduction was seen even with increasing compound concentrations (Figure 1C). Therefore, it was concluded that Compound 22 does not inhibit kinases to facilitate its action. The whole data of the kinase screen is summarized in Table S1.

A) Chemical structure of Compound 22 with its tetrazolo-pyridazine moiety B) Dendrogram of all kinases inhibited by more than 50% by 10 µM of Compound 22. The only hit was GRK6. C) IC50 validation of the inhibition of Compound 22 on the GRK6 activity. D) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes after 24 h of 10 µM treatment with Compound 22. Red dots indicate genes changed for more than -1.7 log2(fold change) and green dots more than +1.7 log2(fold change). Grey dashed lines indicate the cut-off of ± 1.7 log2(fold change).

RNA-sequencing reveals altered NFkB pathway signature under Compound 22 treatment

The NFĸB signaling pathway was first proposed as possible attenuated pathway in the discovery publication of Compound 22 [6]. Since Compound 22 reduces the gene expression of MACC1, the next step in the deconvolution of the MoA of Compound 22 was a transcriptomics approach using RNA-sequencing. HCT116 cells were treated with 10 µM Compound 22 for 24 h or DMSO as negative control. As seen in in the volcano plot of Figure 1C, a limited number of genes was affected, resulting in a small list of strongly up- or down-regulated genes when a commonly used cut-off of ± 1.7 log2(fold change) was applied. MACC1 gene expression was reduced by

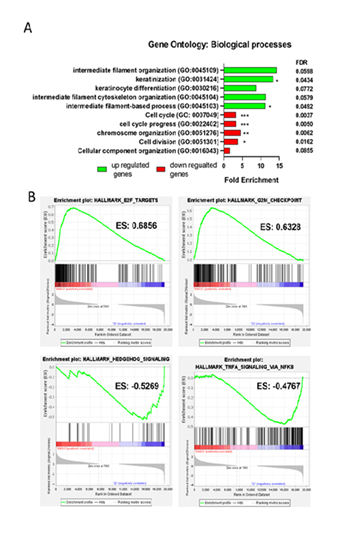

-0.486 log2(fold change) which reflects a degree of inhibition which was previously reported [6]. To gain insight into biological processes associated with the DEGs, a gene ontology (GO) analysis was performed. Because only a distinct subset of genes was strongly affected, the cut-off was set to ±1 log2(fold change). This resulted in 165 up- and 194 down-regulated genes which were analyzed separately for enrichment of biological processes. The top 5 biological processes for each regulation type are displayed in Figure 2A. Among the up-regulated genes, the most enriched biological process was intermediate filament organization and the only statistically significant processes were keratinization and intermediate filament-based process (FDR < 0.05). In contrast, down-regulated genes were significantly associated with cell cycle, cell cycle progress, chromosome organization and cell division (FDR < 0.01).

After analyzing the biological processes of the DEGs, a gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted with the hallmark of cancer gene set (Figure 2B). The two most positively enriched gene sets were E2F targets and G2M checkpoint (ES > 0.6). On the other hand, the most negatively enriched gene sets were Hedgehog signaling and TNFA signaling via NFKB (ES < -0.45). Due to the limited number of genes in the Hedgehog signaling gene set, TNFA signaling via NFKB was ruled out to have a stronger biological impact. Moreover, no connection in the literature was found between MACC1 and hedgehog signaling. However, it has been reported before that MACC1 is a target gene of TNF-α induced NFκB signaling 8. Therefore, this pathway was explored further for the MoA deconvolution of Compound 22.

HCT116 cells were treated with 10 µM Compound 22 or DMSO as negative control for 24 h.

A) Gene ontology analysis of biological processes of up- (green) and down-regulated (red) genes. B) Gene set enrichment analysis of differentially expressed genes. ES = enrichment score. Statistical significance was taken from FDR calculated by the GO enrichment tool (* = FDR < 0.05; ** = FDR < 0.01; *** = FDR < 0.001).

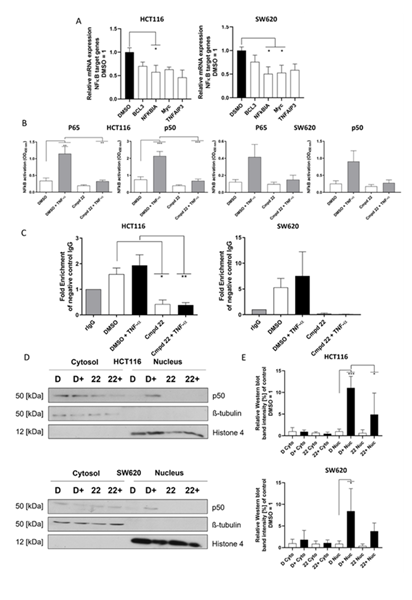

NFĸB target genes are reduced under Compound 22 treatment

To test whether Compound 22 affects NFĸB target genes, a selection of 4 genes which have been listed as NFĸB target genes on the Boston University web page [17] was made. They included B-cell lymphoma 3-encoded protein (BCL3), which is a coactivator for NFĸB p50 and p52 TFs. Further included are Nuclear factor of kappa light polypeptide gene enhancer in B-cells inhibitor alpha (NFKBIA) which is an inhibitor of Rel/NFĸB and MYC proto-oncogene (Myc) which is a proto-oncogene activated by the NFĸB pathway. As a last target gene, we chose Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha-induced protein 3 (TNFAIP3) which is a TNF-inducible zinc finger which gets activated by TNF-α. All target genes were reduced compared to the DMSO solvent control in HCT116 and SW620 cells (Figure 3A). However, most significantly lowered was NFKBIA in both cell lines and Myc in SW620 cells. These results demonstrate that Compound 22 markedly decreases the expression of NFĸB target genes.

A) qRT-PCR analysis of NFĸB target genes (BCL3, NFKBIA, Myc, TNFAIP3) and their expression levels compared to the DMSO negative control in HCT116 (left) and SW620 cells (right). B) ELISA based assay for the activity of NFĸB transcription factors p65 and p50 in HCT116 (left) and SW620 cells (right). Cmpd 22 = Compound 22. C) Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments with p65 as immunoprecipitated protein and subsequent qPCR analysis for RelA binding site on the MACC1 promoter in HCT116 (left) and SW620 cells (right), Cmpd 22 = Compound 22. D) Cellular fractionation experiments in HCT116 (top) and SW620 (bottom) cells for distribution of p50. D = DMSO, D+ = DMSO + TNF-α, 22 = Compound 22, 22+ = Compound 22 + TNF- α. E) Quantification of Western blots for cellular fractionation in HCT116 (top) and SW620 cells (bottom). Cyto = cytoplasma, Nuc = nucleus, D = DMSO, D+ = DMSO + TNF-α, 22 = Compound 22, 22+ = Compound 22 + TNF- α.Quantification was conducted with Image J, calculating the area under the curve to quantify the intensity of the Western blot bands shown in panel D, which were then normalized to the respective loading control (β-tubulin for cytoplasmic fraction and histone 4 for nuclear fraction) and DMSO control for each fraction separately. Statistical significance was calculated using ordinary one-way ANOVA with subsequent multiple comparison done with Dunnett’s post-test for A-B) and Tukey post-test for C-D) using GraphPad prism version 8.02 (* = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001).

p65 and p50 activity is blocked by Compound 22

After confirming the inhibitory effect of Compound 22 on target genes of the NFĸB signaling pathway, we explored the activity of the main TFs p65 and p50 with an ELISA-based NFĸB activation assay. HCT116 and SW620 cells were pretreated with 10 µM of Compound 22 for 1 h and then stimulated with 100 ng/mL TNF-α for 90 min. The whole cell lysate of the cells was then analyzed for the activation level of p65 and p50. In both cell lines a strong activation of TFs in the DMSO control can be seen upon TNF-α stimulation compared to the non-stimulated DMSO control (Figure 3B). Compound 22 pretreatment reduced this effect significantly and no increase of activity was seen after TNF-α stimulation in the HCT116 cell line and a strong reduction was seen in SW620 cells. The sole treatment with Compound 22 already reduced the activity of p65 and p50 compared to the non-stimulated DMSO control.

Moreover, a chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) experiment was conducted to see if this reduction of activity is translated to the MACC1 promoter. For this experiment the amount of MACC1 promoter which was pulled by a p65 antibody in the immunoprecipitation was measured with a qPCR. Primers which span the first predicted binding site for p65 on the MACC1 promoter were used [8]. HCT116 and SW620 cells were pretreated with 10 µM Compound 22 or DMSO as negative control for 3 h and the NFĸB signaling pathway was activated for 15 mins with 100 ng/mL of TNF-α. It was shown for both cell lines that the induction of the NFĸB signaling pathway by TNF-α increased the amount of MACC1 promoter captured in this assay, indicating an increased activity of p65 on the MACC1 promoter in the DMSO control stimulated with TNF-α (Figure 3C). The treatment of Compound 22 significantly inhibited this effect of NFĸB induction by TNF-α in the HCT116 cells and strongly reduced it in SW620 cells. The reduction of the activity was even below the DMSO non-stimulated control level. Here again, a reduction was visible when the cells were pretreated with only Compound 22 compared to the DMSO control without any induction of the NFĸB pathway. In conclusion, we demonstrate with two different approaches, that the activity of the main TFs p65 and p50 of the NFĸB signaling pathway is blocked under Compound 22 treatment.

Compound 22 blocks nuclear translocation of p50

To evaluate the effect of Compound 22 on the spatial distribution of NFĸB TFs, a cellular fractionation experiment was conducted to analyze the spatial distribution of p50. For this, a cellular fractionation of the cytosol and the nucleus was carried out. HCT116 and SW620 cells were treated with 10 µM Compound 22 or equal amount of the solvent (DMSO) as negative control for 3 h. Then the pathway was activated with 100 ng/mL of TNF-α for 15 min. Cells were lysed and the cellular fractions were separated. It can be seen in the Western blots in Figure 3D that the cytosol (ß-tubulin as marker) was successfully separated from the nuclear fraction (histone 4 as marker). The p50 activity was slightly reduced in HCT116 cells but not in SW620 cells in the cytosol fraction upon Compound 22 treatment. In contrast, in the nuclear fraction a more intense band for p50 can be seen upon TNF-α stimulation in the DMSO control but not if the cells were pretreated with Compound 22. Therefore, a clear reduction can be seen for the nuclear translocation of p50. This was further shown in the quantification of the Western blots (Figure 3E) which shows a significant reduction in the amount of p50 for the Compound 22 and TNF-α treated HCT116 cells compared to the DMSO negative control treated with TNF-α. Overall, pretreatment with Compound 22 reduces the nuclear translocation of p50 upon TNF-α stimulation.

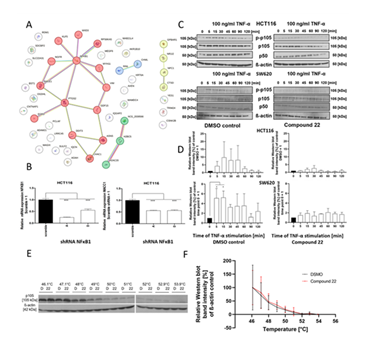

Target prediction reveals p105 as possible target of Compound 22

In collaboration with the Charité (group of R. Preissner), a prediction on possible protein targets of Compound 22 was conducted using logistic regression models which were trained on extended-connectivity fingerprints. A vectorized representation of the topological features of the chemical compound was used for machine learning-based classification. The prediction system output consists of the predicted probability and model accuracy. The latter served as a cut-off of 0.7 to ensure confidence in the predictions. A compelling hit was NFĸB p105 subunit, which is part of the non-canonical NFκB signaling pathway and presented a probability of 88.6% and a high model accuracy of 96% (Table S2).

This list of predicted proteins was integrated with the most highly regulated genes (± 1.5 log2(fold change)) of the DEG list which included 21 down-regulated and 28 up-regulated genes in the analysis. For possible connections between the proteins and genes, the string-db [18] was used. Surprisingly, 7 of the predicted proteins (CTSD, NR1I2, NPC1, TRIM24, YES1, CSNK2B and GPBAR1) did not show any connection to any genes analyzed (Figure 4A). The most prominent candidate was NFKB1, which was clustered together with 6 of the top regulated genes such as the most up-regulated gene NGFR. Of these connections, 5 had experimental data validating the connection. Moreover, KLF5 and PTGS2, which itself clustered with 4 of the integrated genes, showed a connection to NFKB1. Due to the greater number of possible connections with the highly regulated genes and a higher model accuracy of NFKB1 over PTGS2 (90%) and KLF5 (86%), the protein expressed by NFKB1 (p105) was further analyzed as possible protein target.

Knockdown studies using shRNA of NFKB1 were conducted in HCT116 cells. It was shown that the knockdown was successful, displayed by a reduced NFKB1 gene expression of shRNA A and D compared to the scramble control (Figure 4B). Furthermore, knockdown of NFKB1 also reduced the MACC1 gene expression significantly compared to the scramble negative control. This indicates that p105 and its gene NFKB1 can regulate the gene expression of MACC1 and are a possible protein target of Compound 22.

A) Connections of predicted protein targets (see Table S2) with the most up- and down-regulated genes (±1.5 log2(fold change)). In red, blue, green and yellow highlighted clusters calculated through k-mean clustering of the string-db tool. Depicted in red the cluster to which p105 (NFKB1) belongs and which has the only protein targets NFKB1, PTGS2 and KLF5 connected to the regulated genes. B) Knockdown experiment with shRNA for NFKB1 in HCT116 cells. On the left NFKB1 expression and on the right MACC1 expression after NFKB1 knockdown. C) Western blot analysis of p105 activation via TNF-α stimulation after 3 h pretreatment with DMSO negative control (left) or Compound 22 (right) of the NFĸB signaling pathway in HCT116 (top panel) and SW620 cells (bottom panel). ß -actin served as loading control. D) Quantification of the phosphorylation of Western blots normalized to total ß-actin and total p105. The 0 min time point was set to 1 (black). E) CETSA analysis for compound binding to p105 after DMSO or Compound 22 treatment of HCT116 cells via Western blot. D = DMSO, 22 = Compound 22. F) Quantification of the CETSA Western blot: in black the quantification of the DMSO negative control and red the quantification of Compound 22 treatment effects. Quantification of Western blots was conducted with Image J, calculating the area under the curve to quantify the intensity of the Western blot bands which were then normalized to the β-actin loading control and DMSO control for 46.1 °C which was set to 100%. Statistical significance was performed using ordinary one-way ANOVA with subsequent multiple comparison done with Dunnett’s post-test for B, D) using GraphPad prism version 8.02 (* = p < 0.05; ** = p < 0.01; *** = p < 0.001).

Phosphorylation of p105 is reduced under Compound 22 treatment

Next, it was tested whether Compound 22 changes the functionality of p105. To address this, HCT116 cells and SW620 cells were incubated for 3 h with 10 µM Compound 22 or DMSO solvent control and then stimulated with 100 ng/mL of TNF-α for 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 90 and 120 min. The phosphorylation status of p105 was then analyzed using Western blotting. It was shown that after 5 min of TNF-α stimulation a strong increase in the band intensity for phosphorylated p105 was visible in the DMSO solvent control samples for both cell lines (Figure 4C). This effect was visible for 45 min before the intensity of the phosphorylated p105 band was fading away over time. However, in the Compound 22 treated samples, the activation of phosphorylation failed and no visible difference can be seen between the non-activated (time point 0) and activated samples. The quantification confirmed that this effect is true even when normalized to the loading control β-actin and total p105 protein (Figure 4D). A change in phosphorylation status of p105 provides a first indication that p105 indeed is a target of Compound 22.

Molecular docking predicts binding of Compound 22 to death domain of p105

The reduction of phosphorylation of p105 by Compound 22 treatment led to the hypothesis that Compound 22 can bind close to the phosphorylation (SER 932) site which is structurally right behind the death domain of p105 and sterically hinder its phosphorylation. Therefore, we docked Compound 22 onto a published solution NMR structure of the death domain of p105 and determined its docking score (Figure 5A). Compound 22 displayed a docking score of 45.1. The molecular docking predicts binding of the tetrazolo-pyridazine part of Compound 22 to ALA 54, PRO 55 and SER 56, the sulfur bridge and the sulfur atom in the thiadiazole interact with TRP 33, the thiadiazole with ASN 32 and PRO 27, which also interacts with the distal phenolic ring (Figure 5B).

A) 3D visualization of predicted binding of Compound 22 to the death domain of p105, viewed from different angles. Yellow: p105 death domain; grey/blue: Compound 22. B) 2D visualization of predicted molecular interactions of Compound 22 with specific amino acid residues of the death domain of p105. The type of interaction is indicated by the color bar, light green: van der Waals, green: conventional hydrogen bond, purple: Pi-Sigma, Orange: Pi-Sulfur, pink: Pi-Alkyl. The protein database entry 2DBF was used to predict the interaction of Compound 22 with p105.

CETSA reveals minimal thermal shift of p105 under Compound 22 treatment

To further validate p105 as a possible target of Compound 22, a cellular thermal shift assay (CETSA) was conducted. For this, HCT116 cell suspension was incubated for 1 h with 10 µM Compound 22 or DMSO solvent control. Then cells were separated into qPCR tubes which were heated for 3 min at increasing temperature with around 1°C steps (46.1-53.9°C). Western blotting revealed the degree of degradation induced by the heat on p105. It can be seen that the DMSO treated sample is degrading slightly faster, displaying a minimal shift compared to the Compound 22 treated sample in the Western blot which is most apparent at 48°C (Figure 4E). Western blot quantification revealed a non-significant thermal shift between the DMSO solvent control and Compound 22 treated samples (Figure 4F). Further experimental evidence is needed to confidently render p105 a target protein of Compound 22.

Discussion

CRC and especially the metastatic spread of the disease still pose a great threat for health and lives of millions of people worldwide. To address this medical need, the development of anti-metastatic therapies is highly needed. Within the drug development pipeline, the exploration of the MoA of a novel compound is an important step, although not entirely essential. About 7 [19] -18% [20] of FDA approved drugs have only limited understanding of their target and MoA [21]. Not only does the understanding of the MoA contribute to further optimization of a substance to its target and better dosing through monitoring of its efficacy but further aids to understand affected pathways to ensure a high safety profile [22]. Drug candidates have a higher clinical success rate if the target and MoA is better understood, exemplified by a higher success rate of approval for kinase inhibitors compared to cytotoxic drugs in the oncology field [23].

In this study we have explored the MoA of a novel anti-metastatic compound named Compound 22, which targets the expression of MACC1, a well know key metastatic molecule [7, 8]. An early hypothesis on the attenuation of the NFĸB signaling pathway by Compound 22 was developed through a literature search. Here the compound Ro106-9920 was revealed which has been described as NFĸB inhibitor [9]. This compound bears the same tetrazolo-pyridazine ring structure as Compound 22 with an oxidized sulfur bridge.

Starting with a kinase profiler assay, we demonstrated that Compound 22 does not inhibit kinases to facilitate its action on the MACC1 gene expression. This was ruled out due to well-known features of common kinase inhibitors such as a low molecular effective concentration, which usually is within the nanomolar range [24] and the lack of inhibition on a variety of kinases presented in the assay, which is commonly seen for competitive kinase inhibitors [25]. Compound 22 failed to reach predefined thresholds (>50% inhibition = partial hit, >70% inhibition = full hit) in the initial screen and IC50 validation for the strongest kinase hit.

After this, RNA-seq was conducted to retrieve DEGs and get insight into the possible attenuated pathways. Subsequent analysis of the data set confirmed the first hypothesis of attenuated NFκB signaling via a GSEA, displaying a negative ES under Compound 22 treatment. It was shown before, that TNF-α can induce the expression of MACC1 [10], supporting the finding that an attenuated NFκB pathway reduces the MACC1 gene expression under Compound 22 treatment.

Moreover, it was shown that E2F targets and G2M checkpoint gene sets which both play a role in cell cycle progression [15] have a positive enrichment score. The genes which are part of the gene sets are enriched in the top of the gene set and indicate a higher activity under DMSO control conditions, essentially being down-regulated by Compound 22. Both gene sets have been shown to be the most consistently upregulated gene sets in a pan-cancer analysis [26] and therefore are commonly found to be dysregulated in cancer cell lines. A reduction of these gene sets may be of use to tackle the malignant phenotype presented by cancer cells. The GSEA findings correlated with the gene ontology analysis of negatively regulated genes being associated with cell cycle and cell cycle progression. This demonstrates that treatment of Compound 22 reduced cell cycle progression by inhibiting the G2M checkpoint and this leads to reduced proliferation which was displayed by a reduced wound healing capacity during the discovery of Compound 22 [8]. This action is attributed to MACC1 inhibition, but as shown here may be due to general cell cycle arrest as well. It has been shown that reducing Cyclin B1, a regulatory subunit of M-phase with specific siRNAs in different cancer cell lines such as MCF-7 leads to an arrest in G2/M phase which in turn leads to a reduced proliferation and increased apoptosis [27] exemplifying the usefulness of targeting the G2/M checkpoint. There is no direct link reported for MACC1 with the G2/M checkpoint. However, treating CRC cells with saffron stalls the cells at the G2/M checkpoint and this effect was more pronounced in MACC1 high expressing cells [28]. But it is not known whether MACC1 regulates the G2/M checkpoint or this is caused through secondary effects such as metabolic stress.

Next to the biological processes mediated by the down-regulated genes, the up-regulated genes under Compound 22 treatment indicate biological processes promoting mesenchymal to epithelial transition (MET) and a more epithelial phenotype. Metastasis formation typically involves epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT) [29], during which intermediate filaments (Ifs) such as keratins (epithelial cell type) and vimentins (mesenchymal cell type) are dysregulated [30]. This IF switch - from keratin down-regulation to vimentin up-regulation [31] is a hallmark of EMT and enhances motility, invasiveness [32], resistance to shear stress [33], and metastatic potential [34].

NFκB signaling promotes vimentin transcription and accelerates EMT [35, 36], while its inhibition reverses these effects [36, 37]. Accordingly, the most up-regulated genes are enriched in IF organization and keratin-related processes such as keratinization and keratinocyte differentiation. These processes reinforce epithelial characteristics. Keratinization, the terminal differentiation of keratinocytes [38], is also linked to EMT programs in cancer and wound healing where cancer cells adopt keratinocyte-like EMT programs to loosen cell-cell adhesion and increase migratory abilities [39], both regulated by transcription factors like Snail and Twist [40]. Reduced NFκB signaling enhances keratinization and epithelial identity [41], counteracting EMT and invasive behavior.

Overall, Compound 22 suppresses genes driving cell cycle progression and division, while up-regulating IF-based structural reorganization towards an epithelial-like state with reduced migration and metastatic potential. Additionally, lower NFκB activity decreases MACC1 expression, which correlates with reduced vimentin levels and EMT signaling [42]. Moreover, the same TF Snail which regulates EMT and keratinocytes wound healing has been shown to interact with MACC1 [43]. These findings of the genetic alterations witnessed upon Compound 22 treatment reveal that Compound 22 mitigates EMT, cell cycle progression and proliferation through NFκB pathway inhibition and MACC1 suppression. However, potential off target effects such as on wound healing in normal tissues of cancer patients should be further examined.

The molecular analysis on the NFκB signaling pathway after treatment with Compound 22 displayed a reduced activity of the main TFs p65 and p50 in the cytoplasm but further a reduced binding of p65 in the cell nucleus on the MACC1 promoter and a strong reduction of nuclear translocation of p50. We have linked the action of Compound 22 on the NFκB signaling pathway to the protein p105 which has reduced phosphorylation upon TNF-α stimulation of the cells under Compound 22 treatment. This protein was the most probable protein target from our in-silico prediction after matching it with the top regulated genes of the DEG list. Moreover, with a very high model accuracy of 96% and molecular docking predictions, the confidence for p105 being a protein target of Compound 22 was strengthened. The p105 protein is the precursor of p50 and, upon phosphorylation, can be processed into p50, which can then regulate gene transcription. Further, the c-terminal domain of p105 can bind NFκB subunits such as p65 and retain them in the cytoplasm and releases them upon activation. The p50 subunit, which is processed from p105 can bind p65, forming heterodimers that can regulate gene transcription [44]. Since no kinase has been shown to be inhibited by Compound 22 and IKKβ, which phosphorylates p105, was also not affected, the most plausible molecular action is the binding of Compound 22 to p105. We predicted through molecular docking, that Compound 22 is able to bind to the death domain of p105, which is located in close proximity to the phosphorylation site SER 932. We hypothesize that Compound 22 sterically hinders the phosphorylation through the binding to the death domain. It has been reported that the death domain is functionally crucial for the signal-induced phoshporylation of p105 [45]. The CETSA experiment showed a non-significant thermal shift, however not all protein-small molecule interactions spark a change in thermal stability of the protein and even when no strong changes are observed, ligands may still bind to the protein of interest [46]. In this regard, more evidence is needed to validate the interaction, ideally using an assay that measures the direct compound to target binding. However, a first hypothesis and possible protein target of Compound 22 was explored.

In conclusion, Compound 22 reduced the MACC1 gene expression by inhibiting the NFκB signaling pathway by possibly binding to p105 and thereby reducing its activity which decreases the activity and nuclear translocation of p65 and p50 TFs. This in turn reduces migratory, wound healing and metastasis forming capabilities and drives the cell into a more epithelial like state by the novel interventional combination of transcriptional inhibition of MACC1 and inhibition of the NFκB signaling.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: P.C.S., U.S.; methodology: P.C.S., M.D., D.K., B.G., A.M.S., W.W., R.P., M.Z., U.S.; validation: P.C.S., B.G., A.M.S.; formal analysis: P.C.S., B.G., A.M.S.; investigation: P.C.S., B.G., A.M.S.; resources: P.C.S., B.G., R.P., U.S.; data curation: P.C.S., B.G., A.M.S., R.P., U.S.; writing original draft preparation: P.C.S., U.S.; writing review and editing: P.C.S., W.W., U.S.; visualization: P.C.S., A.M.S.; supervision: D.K., W.W., R.P., M.Z., U.S.; project administration: R.P., U.S. ; funding acquisition: P.C.S., U.S.; advisory: M.D., D.K., W.W., M.Z., U.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Paul Curtis Schöpe was funded by the Berlin School of Integrative Oncology (BSIO) from 01/2021-12/2024 and further funded with a stipend by the Charité - Universitätsmedizin Berlin from 01/2025-12/2025. Moreover, this study was funded by the SPARK program of the Berlin Institute of Health (BIH) from 2021-2023.

Acknowledgments

We want to acknowledge and thank Dr. Marina Kolesnichenko for providing the primers for the NFĸB target genes. Moreover, we want to thank Luca Elschner and Janice Smith for their valuable technical support in the lab.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- Guan X. Cancer metastases: challenges and opportunities. Acta Pharm Sin B 5 (2015): 402-418.

- Dillekås H, Rogers MS, Straume O. Are 90% of deaths from cancer caused by metastases? Cancer Med 8 (2019): 5574-5576.

- Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, et al. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 74 (2024): 229-263.

- National Cancer Institute. Cancer Statistics: Colorectal Cancer. SEER Program (2025).

- Radhakrishnan H, Walther W, Zincke F, et al. MACC1—the first decade of a key metastasis molecule from gene discovery to clinical translation. Cancer Metastasis Rev 37 (2018): 805-820.

- Schöpe PC, Torke S, Kobelt D, et al. MACC1 revisited—an in-depth review of a master of metastasis. Biomark Res 12 (2024): 146.

- Stein U, Walther W, Arlt F, et al. MACC1, a newly identified key regulator of HGF-MET signaling, predicts colon cancer metastasis. Nat Med 15 (2009): 59-67.

- Yan S, Schöpe PC, Lewis J, et al. Discovery of tetrazolo-pyridazine-based small molecules as inhibitors of MACC1-driven cancer metastasis. Biomed Pharmacother 168 (2023): 115698.

- Swinney DC, Xu YZ, Scarafia LE, et al. A small molecule ubiquitination inhibitor blocks NF-kappa B-dependent cytokine expression in cells and rats. J Biol Chem 277 (2002): 23573-23581.

- Kobelt D, Zhang C, Clayton-Lucey IA, et al. Pro-inflammatory TNF-α and IFN-γ promote tumor growth and metastasis via induction of MACC1. Front Immunol 11 (2020): 980.

- Batut B, Freeberg M, Heydarian M, et al. Reference-based RNA-Seq data analysis (Galaxy Training Materials). Galaxy Project (2016).

- Hiltemann S, Rasche H, Gladman S, et al. Galaxy Training: A powerful framework for teaching. PLOS Comput Biol 19 (2023): e1010752.

- Batut B, Hiltemann S, Bagnacani A, et al. Community-driven data analysis training for biology. Cell Syst 6 (2018): 752-758.

- The Gene Ontology Consortium. The Gene Ontology Resource: 20 years and still GOing strong. Nucleic Acids Res 47 (2019): D330-D338.

- Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, et al. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst 1 (2015): 417-425.

- Jafari R, Almqvist H, Axelsson H, et al. The cellular thermal shift assay for evaluating drug target interactions in cells. Nat Protoc 9 (2014): 2100-2122.

- Boston University Biology. NF-kB Target Genes. Boston University (2025).

- Szklarczyk D, Kirsch R, Koutrouli M, et al. The STRING database in 2023: protein-protein association networks and functional enrichment analyses. Nucleic Acids Res 51 (2023): D638-D646.

- Drews J. Drug discovery: a historical perspective. Science 287 (2000): 1960-1964.

- Overington JP, Al-Lazikani B, Hopkins AL. How many drug targets are there? Nat Rev Drug Discov 5 (2006): 993-996.

- Moffat JG, Vincent F, Lee JA, et al. Opportunities and challenges in phenotypic drug discovery: an industry perspective. Nat Rev Drug Discov 16 (2017): 531-543.

- Mechanism matters. Nat Med 16 (2010): 347.

- Yamaguchi S, Kaneko M, Narukawa M. Approval success rates of drug candidates based on target, action, modality, and application. Clin Transl Sci 14 (2021): 1113-1122.

- Kooijman JJ, van Riel WE, Dylus J, et al. Comparative kinase and cancer cell panel profiling of kinase inhibitors approved for clinical use from 2018 to 2020. Front Oncol 12 (2022): 953013.

- Duong-Ly KC, Peterson JR. The human kinome and kinase inhibition. Curr Protoc Pharmacol Chapter 2 (2013): Unit2.9.

- Masood MBE, Shafique I, Rafique MI, et al. Integrated pan-cancer analysis revealed therapeutic targets in the ABC transporter protein family. PLoS One 20 (2025): e0308585.

- Yuan J, Yan R, Krämer A, et al. Cyclin B1 depletion inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in human tumor cells. Oncogene 23 (2004): 5843-5852.

- Güllü N, Kobelt D, Brim H, et al. Saffron crudes and compounds restrict MACC1-dependent cell proliferation and migration of colorectal cancer cells. Cells 9 (2020): 1829.

- Lu W, Kang Y. Epithelial-mesenchymal plasticity in cancer progression and metastasis. Dev Cell 49 (2019): 361-374.

- Mackinder MA, Evans CA, Chowdry J, et al. Alteration in composition of keratin intermediate filaments in a model of breast cancer progression. Cancer Biomark 12 (2012): 49-64.

- Yang J, Antin P, Berx G, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition: the story continues. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 21 (2020): 341-352.

- Mendez MG, Kojima S, Goldman RD. Vimentin induces changes in cell shape, motility, and adhesion during epithelial to mesenchymal transition. FASEB J 24 (2010): 1838-1851.

- Infante E, Etienne-Manneville S. Intermediate filaments: integration of cell mechanical properties during migration. Front Cell Dev Biol 10 (2022): 951816.

- Strouhalova K, Přechová M, Gandalovičová A, et al. Vimentin intermediate filaments as potential target for cancer treatment. Cancers (Basel) 12 (2020): 184.

- Li CW, Xia W, Huo L, et al. Epithelial-mesenchymal transition induced by TNF-α requires NF-κB-mediated transcriptional upregulation of Twist1. Cancer Res 72 (2012): 1290-1300.

- Oh A, Pardo M, Rodriguez A, et al. NF-κB signaling in neoplastic transition from epithelial to mesenchymal phenotype. Cell Commun Signal 21 (2023): 291.

- Nomura A, Majumder K, Giri B, et al. Inhibition of NF-kappa B pathway leads to deregulation of epithelial-mesenchymal transition in pancreatic cancer. Lab Invest 96 (2016): 1268-1278.

- Maranduca AM, Hurjui L, Branisteanu CD, et al. Skin—a vast organ with immunological function. Exp Ther Med 20 (2020): 18-23.

- Leopold PL, Vincent J, Wang H. A comparison of epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition and re-epithelialization. Semin Cancer Biol 22 (2012): 471-483.

- Haensel D, Dai X. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition in cutaneous wound healing. Dev Dyn 247 (2018): 473-480.

- Adams S, Pankow S, Werner S, et al. Regulation of NF-kappaB activity and keratinocyte differentiation by RIP4 protein. J Invest Dermatol 127 (2007): 538-544.

- Zhen T, Dai S, Li H, et al. MACC1 promotes carcinogenesis of colorectal cancer via β-catenin signaling pathway. Oncotarget 5 (2014): 3756-3769.

- Zhang X, Luo Y, Cen Y, et al. MACC1 promotes pancreatic cancer metastasis by interacting with the EMT regulator SNAI1. Cell Death Dis 13 (2022): 923.

- Guo Q, Jin Y, Chen X, et al. NF-κB in biology and targeted therapy: new insights and translational implications. Signal Transduct Target Ther 9 (2024): 53.

- Beinke S, Belich MP, Ley SC. The death domain of NF-kappa B1 p105 is essential for signal-induced p105 proteolysis. J Biol Chem 277 (2002): 24162-24168.

- Monteagudo-Cascales E, Cano-Muñoz M, Genova R, et al. Thermal shift assay to identify ligands for bacterial sensor proteins. FEMS Microbiol Rev 49 (2025): fuaf033.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 75.63%

Acceptance Rate: 75.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks