Impact of Clenching on Range of Motion of Hip Joint and Lumbar Spine in Rugby Players

Mutsumi Takahashi*,1, Yogetsu Bando2, Takuya Fukui3, Masaaki Sugita4

1Department of Physiology, The Nippon Dental University School of Life Dentistry at Niigata, Japan

2Bando Dental Clinic, Ishikawa, Japan

3Department of Sport Science, Kanazawa Gakuin University of Sport Science, Ishikawa, Japan

4Faculty of Sport Science, Nippon Sport Science University, Tokyo, Japan

*Corresponding Author: Mutsumi Takahashi, Department of Physiology, The Nippon Dental University School of Life Dentistry at Niigata, Japan

Received: 26 December 2025; Accepted: 06 January 2026; Published: 09 January 2026

Article Information

Citation: Mutsumi Takahashi, Yogetsu Bando, Takuya Fukui, Masaaki Sugita. Impact of Clenching on Range of Motion of Hip Joint and Lumbar Spine in Rugby Players. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 9 (2026): 36-41.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

The purpose of this study was to clarify the influence of occlusion on the range of motion of the hip joint and lumbar spine in rugby players. Participants were 39 male rugby players. Cross-test was performed without any instructions regarding occlusion, and participants were divided into that clenched during measurement (occlusal group) and other (non-occlusal group). Next, spinal shape was measured in a static standing position and a standing forward bending position under the conditions of the mandibular rest position (RP) and clenching (CL), and the hip joint range of motion (HJM), lumbar range of motion (LM), and spinal range of motion (SM) were calculated. Differences in HJM, LM, and SM according to participant groups and occlusal conditions were analyzed. Additionally, the reduction rate in range of motion for each alignment due to clenching was calculated, and differences between participant groups and spinal alignment were analyzed. In HJM, LM, and SM, CL was significantly lower than RP in both groups. The reduction rate in HJM was higher in the occlusal group, and that in LM was higher in the non-occlusal group (P<0.01). The greatest reduction rate among spinal alignments was observed in HJM in the occlusal group and in LM in the non-occlusal group (P<0.01). This study suggested that rugby players who clench their teeth during shifting their center of gravity have excellent dynamic balance, and that tend to use their hip joints when flexing their trunk. However, other athletes tended to use their lumbar spine when flexing their trunk.

Keywords

<p>Spinal alignment; Hip joint range of motion; Lumbar range of motion; Spinal range of motion; Trunk flexion; Occlusion; Clenching; Rugby</p>

Article Details

Introduction

Balance ability can be divided into static balance, which involves adjusting posture to maintain the center of gravity within the base of support in a fixed location, and dynamic balance, which involves adjusting posture in an unstable environment where the base of support or center of gravity changes [1,2]. The center of gravity can be smoothly shifted through flexibility of the hip joint, flexibility of deep joint muscles such as the iliopsoas and obturator internus and externus, and spinal movement linked to the lumbar vertebrae. Hip joint movement consists of six movements—flexion, extension, adduction, abduction, internal rotation, and external rotation—and trunk flexion can be considered to be a range of motion of the hip joint that is primarily flexion. If the range of motion of the hip joint is limited, the pelvis tilts forward, causing the lumbar vertebrae to compensate for the movement. The ankle joints cannot be linked together when the center of gravity is shifted, placing excessive strain on the ankle and knee joints as well as the ligaments [3].

One device for measuring spinal alignment non-invasively is the spinal shape analyzer (Spinal Mouse). A feature of this device is that the measurement of the sacral tilt angle in a knee-extended position corresponds to the range of motion of the hip joint [4,5]. We previously investigated the effects of clenching on hip joint range of motion and dynamic balance, finding that there was a positive correlation between hip joint range of motion and dynamic balance and that spinal movement and dynamic balance were affected by clenching [3,5]. In other words, the greater the range of motion of the hip joint, the better the dynamic balance, and the range of motion of the hip joint is affected by the balance of occlusal contacts. Furthermore, in the cross-test used to assess dynamic balance, a questionnaire survey conducted after the measurement revealed that some participants utilized their occlusion (i.e., clenching) while moving their upper body, whereas others did not occlude at all. From this, it was inferred that the way spinal alignment is utilized may differ depending on the degree of occlusion when shifting the center of gravity. In addition, spinal alignment tends to be modified by environmental factors such as lifestyle and work posture [6,7]. Approximately 60% of athletes experience back pain due to sports, and this pain is prone to recurrence and chronicity [8]. Therefore, it is possible that athletes with a long competitive history may exhibit spinal alignment and mobility issues specific to their sport.

The purpose of this study was to clarify the influence of occlusion on the range of motion of the hip joint and lumbar spine in rugby players. The null hypothesis was that the range of motion of the hip joint and lumbar spine in rugby players is not affected by occlusion.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Participants were 39 male rugby players (mean age 19.4±1.1 years) with no subjective or objective morphological or functional abnormalities in the stomatognathic system. The average competitive experience was 9.7±3.1 years. Exclusion criteria were tooth defects other than in the wisdom teeth, ongoing dental treatment, presence of musculoskeletal pain or severe low back pain within the past 12 months, or a history of surgery in the lower limbs, spine, or pelvis [4,5].

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Nippon Dental University School of Life Dentistry at Niigata (ECNG-R-443). The details of the study were explained in full to all participants and proxies, and their informed consent was obtained.

Measurement of dynamic balance

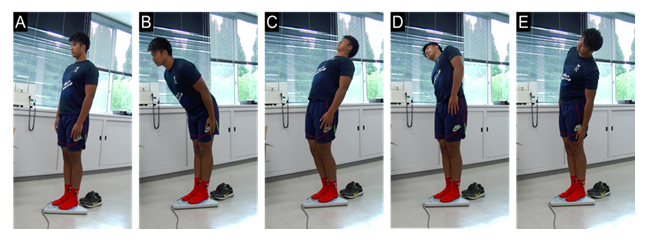

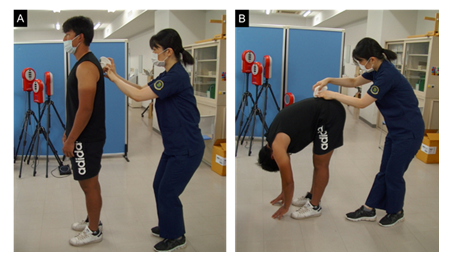

Dynamic balance was assessed by conducting a cross-test using a center-of-gravity sway meter (GRAVICORDER GS-7; Anima Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan). Participants stood upright with the center of the sole of each foot 5 cm apart on either side of the reference line on the measurement table while both upper limbs were placed in a natural standing position next to their sides. Participants were instructed to move their upper body from a stationary standing reference position over a 30-sec period (3-sec in each position) in the following order: forward, reference, backward, reference, left, reference, right, and back to reference again (Figure 1) [9]. They were instructed not to bend their upper body during this movement.

First, the cross-test was performed without any instructions regarding occlusion (Free condition). Based on the questionnaire completed after the measurement, participants who clenched their teeth at any point during the measurement were classified as the occlusal group, while those who did not clench their teeth were classified as the non-occlusal group. There were 20 patients in the occlusal group and 19 patients in the non-occlusal group. Next, a similar cross-test was conducted in the mandibular rest position, in which the teeth were not intentionally brought into contact (RP condition).

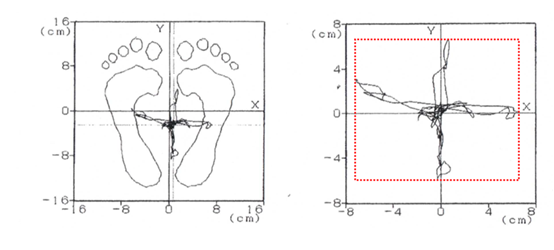

In the center-of-gravity trajectory diagram obtained by the measurement, the rectangular area obtained by multiplying the forward- and backward-movement distance of the center of foot pressure and the left- and right-movement distance was used as an index of dynamic balance (Figure 2).

Measurement of spinal alignment

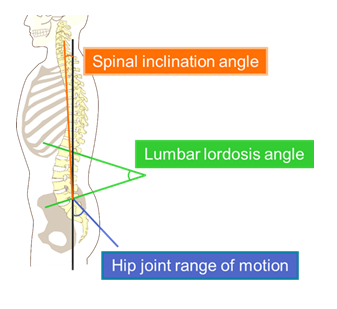

Spinal alignment was measured using a spinal shape analyzer (Spinal Mouse; Index Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) [4,10,11]. The baseline of the device was aligned with the seventh cervical vertebra and moved along the paravertebral line to the third sacral vertebra in order to measure the lumbar lordosis angle, sacral slope angle, and spinal inclination angle (Figure 3). Measurements were performed with the participant in a static standing position and a standing forward bending position (Figure 4). The lumbar range of motion (LM), hip joint range of motion (HJM), and spinal range of motion (SM) were calculated from the measurements of the two postures. The measurement conditions were the mandibular rest position (RP) and clenching in the intercuspal position (CL). One measurement was performed for about 5 sec and the subsequent rest interval was 1 min.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS 17.0 software (SPSS Japan Inc., Tokyo, Japan). Significance was set at P<0.05. The Shapiro–Wilk test was used to examine the normality of distribution and Levene’s test was used for homogeneity of variance.

For the rectangular areas in the occlusal and non-occlusal groups, normality and equal variance were guaranteed for each level of the RP and Free conditions, so a split-plot design was used to compare differences between participant groups or between occlusion conditions. Next, the range of motion for each spinal alignment in the occlusal and non-occlusal groups was compared based on participant group and occlusion condition. Analysis was performed using a split-plot design because normality and homoscedasticity were ensured for all levels. Regarding the significant factors, differences between participant groups were analyzed using Student’s t-test, and differences between occlusion conditions were analyzed using a paired t-test.

In addition, the rate of reduction in range of motion for each spinal alignment due to clenching was calculated, and differences between participant groups and spinal alignment were analyzed using a split-plot design. Because differences between participant group, spinal alignment, and interaction were all significant, participants or spinal alignment was selected for each level, and comparisons between levels were performed using Student’s t-test or one-way analysis of variance with the Bonferroni method.

Results

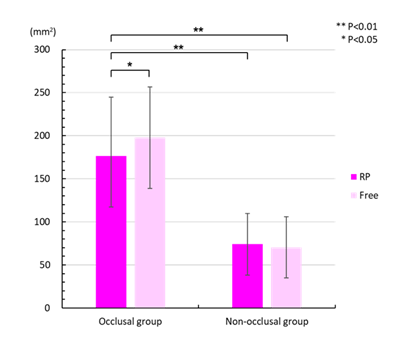

Figure 5 shows the difference in rectangular area between the occlusal and non-occlusal groups. In the RP and Free conditions, the rectangular area of the occlusal group was larger than that of the non-occlusal group (P<0.01). Differences due to occlusal conditions were observed only in the occlusal group, with higher values in the Free condition than in the RP condition (P<0.05).

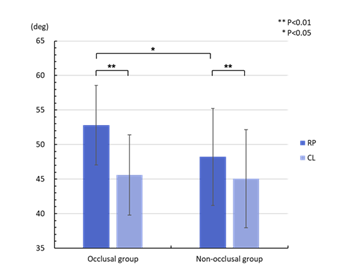

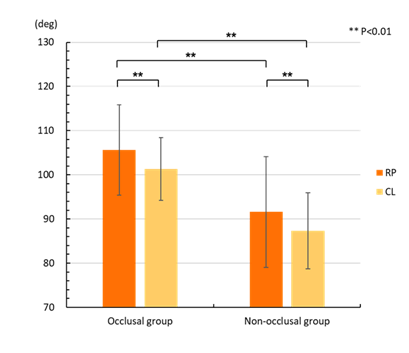

Figure 6 shows a comparison of HJM between the occlusal group and the non-occlusal group. In RP, the occlusal group showed significantly higher values than the non-occlusal group (P<0.05). Differences due to occlusal conditions were observed in both participant groups, with RP showing higher values compared with CL in both cases (P<0.01).

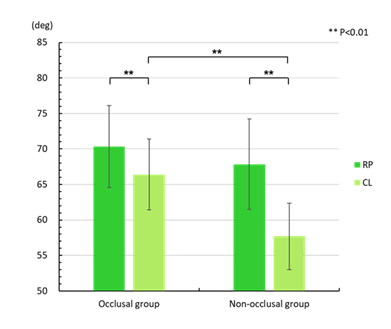

Figure 7 shows a comparison of LM between the occlusal group and the non-occlusal group. In CL, the occlusal group showed significantly higher values compared with the non-occlusal group (P<0.01). Differences due to occlusal conditions were observed in both participant groups, with RP showing higher values compared with CL in both cases (P<0.01).

Figure 8 shows a comparison of SM between the occlusal group and the non-occlusal group. In RP and CL, the occlusal group showed significantly higher values compared with the non-occlusal group (P<0.01). Differences due to occlusal conditions were observed in both participant groups, with RP showing higher values compared with CL in both cases (P<0.01).

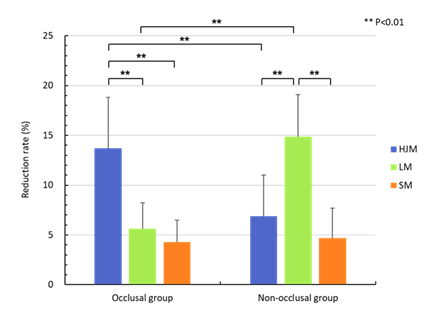

Figure 9 shows a comparison of the rate of reduction in range of motion for each spinal alignment due to clenching between the occlusal group and the non-occlusal group. The rate of reduction in HJM was significantly higher in the occlusal group, and that in LM was significantly higher in the non-occlusal group (P<0.01). In the occlusal group, the reduction rate in HJM was the greatest compared with the reduction rate in LM and SM (P<0.01). In the non-occlusal group, the rate of reduction in LM was the largest compared with the rates of reduction in HJM and SM (P<0.01).

Discussion

The results of this study revealed that clenching of the teeth reduced the range of motion of the hip joint and lumbar spine in rugby players. In addition, the rate of reduction in the range of motion for each spinal alignment due to clenching showed a different trend, depending on whether or not occlusion was utilized when moving the center of gravity. Therefore, the null hypothesis was rejected.

Because static and dynamic balance are affected by occlusal contact state (occlusal balance) [4,5,12-15], previous studies have investigated the influence of occlusion on balance ability by dividing participants into groups with stable occlusal balance and unstable occlusal balance and comparing them, or by investigating the effects of occlusal correction using oral appliances. However, in a previous study using the cross-test to assess dynamic balance [3], several participants with large upper body movements were found to clench their teeth to stabilize their trunks. For this reason, when assessing dynamic balance in the present study, participants were not given instructions regarding occlusion beforehand, and a questionnaire survey conducted after the measurement confirmed whether or not they had clenched their teeth during the measurement. We then investigated the tendency of spinal alignment by dividing the group that utilized clenching into the occlusal group and the group that did not into the non-occlusal group. In the cross-test, the center of gravity is moved forward, backward, left, and right without bending the upper body, so the movement of the ankle and hip joints tends to be more easily reflected in the measurements compared with the lumbar spine. In other words, if the distance traveled by the center of foot pressure is small, the movement will be primarily based on the ankle strategy, resulting in a small rectangular area; if the distance traveled by the center of foot pressure is large, the movement will be based on the hip strategy, resulting in a large rectangular area. The results of this study revealed that the rectangular area was larger in the occlusal group in both the RP and Free conditions. This suggests that the occlusal group may effectively utilize ankle and hip strategies when moving their upper body. Furthermore, the rectangular area of the occlusal group was larger in the Free condition, which involved clenching, than in the RP condition, suggesting that occlusion may have been utilized to stabilize the trunk when moving the upper body.

Regarding the effect of clenching on the range of motion of each spinal alignment, CL was lower compared with RP in the occlusal and non-occlusal groups in the HJM, LM, and SM groups. From this, it can be inferred that, as in previous research [3], this result reflects the fixation of the trunk due to clenching. Regarding differences between participant groups, HJM in the RP condition was greater in the occlusal group. As can be inferred from the rectangular area results, this is likely due to the efficient use of the hip strategy during trunk flexion. However, given that the LM under the CL condition was smaller in the non-occlusal group than in the occlusal group, it was inferred that the lumbar fixation effect of occlusion might be greater in the non-occlusal group. SM is a value that comprehensively reflects the range of motion of spinal alignment, and both RP and CL were higher in the occlusal group than in the non-occlusal group. This suggests that the occlusal group might have had a greater range of spinal motion compared with the non-occlusal group. Therefore, we examined the reduction rate to compare the effect of clenching on the range of motion for each spinal alignment.

When comparing the rate of reduction in range of motion for each spinal alignment due to clenching, no differences were observed between participant groups for SM. This indicates that the effect of clenching on spinal range of motion during trunk flexion is similar in the occlusal and non-occlusal groups. However, the rate of reduction in HJM was greater in the occlusal group, and the reduction rate of LM was greater in the non-occlusal group, indicating that the contribution of each spinal alignment to trunk flexion differs. In the occlusal group, the rate of decrease in HJM was greater than that in LM and SM, whereas in the non-occlusal group, the rate of decrease in LM was greater than that in HJM and SM. In other words, it was suggested that the occlusal group may have used the hip joints to stabilize the trunk through clenching, while the non-occlusal group may have used the lumbar spine. Generally, when the range of motion of the hip joint is small, the lumbar vertebrae are used to compensate, thereby enabling in a large range of motion. Actions that exert muscle strength while maintaining a low posture (i.e., scrumming) are unique to rugby, and during these actions, flexibility in hip flexion, external rotation, and internal rotation are important, as is the muscle strength to support this posture. In addition, by utilizing the linkage with the trunk through the extension and rotation of the thoracic spine, the forward pushing force can be efficiently transmitted to the opposing player. For rugby players, hip mobility and muscle strength are important to avoid excessive strain on the lumbar spine and reduce the risk of injury. This study revealed that clenching of the teeth in rugby players contributes to trunk stability and may also provide evidence of the importance of training to improve hip joint range of motion. In future research, it will be necessary to investigate the range of motion of the thoracic spine and the strength of the muscles around the hip joint as well as to examine the relationship with the range of motion of spinal alignment and trends depending on position.

Conclusion

This study investigated the influence of occlusion on the range of motion of the hip joint and lumbar spine in rugby players and revealed that players who clench their teeth when shifting their center of gravity have excellent dynamic balance, and that these players tend to use their hip joints when flexing their trunk. However, it was suggested that athletes who do not clench their teeth when shifting their center of gravity tend to use the lumbar spine when flexing their trunk.

Data Availability

The datasets collected and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by JSPS KAKENHI Grant Number JP23K10617 and the Nippon Dental University Intramural Research Fund (NDU Grants N-21004). We would like to express our sincere gratitude to Mr. Takeishi of GXA Co., Ltd. for his cooperation in carrying out this research.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article.

References

- Jonsson E, Henriksson M, Hirschfeld H. Does the functional reach test reflect stability limits in elderly people? J Rehabil Med 35 (2003): 26-30.

- Nagano K. Immediate and sustained effects of balance stabilization by the prone abdominal drawing-in maneuver. J Asi Reha Sci 6 (2023): 17-23.

- Takahashi M, Bando Y, Fukui T. Influence of hip joint range of motion on postural stability in trampoline gymnasts. Dent Res Oral Health (2024): 74-79.

- Takahashi M, Bando Y, Fukui T, et al. Effect of clenching on spinal alignment in normal adults. Int J Dent Oral Health 8 (2021): 386.

- Takahashi M, Bando Y, Kitaoka K, et al. Effect of wearing an oral appliance on range of motion of spine during trunk flexion. APE 13 (2023): 288-295.

- Frank S, Virginie L, Reid B, et al. Gravity line analysis in adult volunteers: age-related correlation with spinal parameters, pelvic parameters, and foot position. Spine 31 (2006): E959-967.

- Okuni I, Uchi M, Harada T. Sagittal-plane spinal curvature and center of foot pressure in healthy young adults. J Med Soc Toho 53 (2006): 254-260.

- Miyazaki K, Kasanami R, Munemoto M, et al. The incidence of low-back pain in university rugby players according to the position of the player. Jpn J Orthop Sports Med 26 (2007): 239-251.

- Fukuyama K, Maruyama H. Relationships between the cross test and other balance tests. Phys Ther Sci 25 (2010): 79-83.

- Mannion AF, Knecht K, Balaban G, et al. A new skin-surface device for measuring the curvature and global and segmental ranges of motion of the spine: reliability of measurements and comparison with data reviewed from the literature. Eur Spine J 13 (2004): 122-136.

- Post RB, Leferink VJM. Spinal mobility: sagittal range of motion measured with the Spinal Mouse, a new non-invasive device. Arch Othop Trauma Surg 124 (2004): 187-192.

- Bando Y, Takahashi M, Fukui T, et al. Relationship between occlusal state and posture control function of trampoline gymnasts. J Sports Dent 23 (2019): 14-20.

- Takahashi M, Bando Y, Kitaoka K, et al. Influence of occlusal state on posture control and physical fitness of elite athletes: Examination targeting female handball players. J Sports Dent 24 (2020): 18-25.

- Takahashi M, Bando Y, Fukui T, et al. Equalization of the occlusal state by wearing a mouthguard contributes to improving postural control function. Appl Sci 13 (2023): 4342.

- Takahashi M, Bando Y, Fukui T. Influence of voluntary clenching on spinal range of motion depends on occlusal contact state. APE 13 (2023): 234-243.

Impact Factor: * 6.2

Impact Factor: * 6.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.33%

Acceptance Rate: 76.33%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks