Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Malaria and Anemia Among Pregnant Women Accessing Antenatal Care at the Limbe Regional hospital, Southwest Region of Cameroon

Bejolefack Neola Asongafac1, Nicoline Fri Tanih2, Seraphine Mojoko Eko1, Takamo Peter2,3, Walters Ndaka1, Anna Njunda Londoh2, Abdel Jelil Njouendou*,1

1Department of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon.

2Department of Medical Laboratory science, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon.

3Department of Public Health and Hygiene, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon.

* Corresponding Author: Abdel Jelil Njouendou, PhD Head of service for teaching and research; Senior Lecturer, Department of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon

Received: 7 December 2025; Accepted: 12 December 2025; Published: 22 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Bejolefack Neola Asongafac, Nicoline Fri Tanih, Seraphine Mojoko Eko, Takamo Peter, Walters Ndaka, Anna Njunda Londoh, Abdel Jelil Njouendou. Prevalence and Associated Risk Factors of Malaria and Anemia Among Pregnant Women Accessing Antenatal Care at the Limbe Regional hospital, Southwest Region of Cameroon. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 8 (2025): 1185-1192.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Malaria remains a major global health problem, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, with high morbidity and mortality among pregnant women and children. Vulnerable groups are also exposed to anemia, one of the most common hematological complications of pregnancy.

Objective: This study sought to determine the prevalence and risk factors of malaria and anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care at the Limbe Regional Hospital, Southwest Region of Cameroon.

Methods: A hospital-based cross-sectional study was conducted among 129 pregnant women. Data were collected using an interviewer-administered questionnaire. Microscopy was used to detect malaria parasites, while hemoglobin concentration was measured with an automated hematology analyzer. Descriptive and multivariate logistic regression analyses were applied to identify predictors.

Results: The mean age of participants was 29.4±5.4 years. Malaria and anemia prevalences were 37.21% (95% CI: 28.87–45.55) and 30.23% (95% CI: 22.31–38.16), respectively. Rural residence significantly predicted malaria (aOR=7.769, 95% CI: 3.653–19.481, p=0.001). History of miscarriage increased anemia risk (aOR=3.343, 95% CI:1.112–10.045, p=0.032). Non-use of insecticide-treated nets and low ANC attendance were also associated with higher odds of anemia.

Conclusion: The high burden of malaria and anemia highlights the need for improved ITN access, preventive treatment in rural settings, and early, frequent ANC visits.

Keywords

<p>Malaria; Anaemia; Pregnancy</p>

Article Details

Introduction

Malaria remains a global health problem, especially in sub-Saharan African countries, where it remains endemic. The infection is caused by the plasmodium parasite, primarily the Plasmodium falciparum, through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquitoes [1]. In 2020, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported an estimated 241 million malaria cases and 627,000 deaths worldwide, highlighting the urgent need for effective control and prevention measures [2]. Among the populations at risk, pregnant women are particularly vulnerable to malaria infections due to physiological and immunological changes that occur during pregnancy. These changes can increase susceptibility to malaria, reduce the efficacy of the immune response, and exacerbate the severity of the disease [3]. As a result, malaria during pregnancy poses significant risks to both maternal and fetal health, contributing to high rates of morbidity and mortality in endemic regions [4]. Maternal morbidity associated with malaria includes a range of complications such as severe anemia, which arises from the destruction of red blood cells by the parasite. This can lead to fatigue, weakness, and increased susceptibility to other infections, further compromising maternal health. The burden of maternal morbidity due to malaria underscores the importance of effective prevention and treatment strategies [5]. Placental malaria, characterized by the sequestration of malaria-infected erythrocytes in the placenta, is a particularly severe form of the disease during pregnancy [6]. This condition impairs the transfer of nutrients and oxygen from the mother to the fetus, leading to adverse pregnancy outcomes. Placental malaria is associated with increased risks of preterm birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth, which are major contributors to neonatal morbidity and mortality. Understanding the mechanisms of placental malaria is crucial for developing targeted interventions to mitigate its impact [7]. Preventive strategies for malaria in pregnancy have shown significant promise in reducing the incidence and severity of the disease. Intermittent preventive treatment in pregnancy (IPTp) with sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine (SP) is recommended by the WHO in areas of moderate to high malaria transmission [8]. This involves administering therapeutic doses of sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine at scheduled antenatal visits, which have been shown to reduce maternal malaria episodes, anemia, and adverse pregnancy outcomes [9]. The use of insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) represents another preventive measure, providing a physical barrier against mosquito bites and reducing malaria transmission. The use of ITNs has been associated with substantial reductions in malaria incidence and mortality [10]. This study sought to determine the prevalence and risk factors of malaria and anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care at the Regional Hospital, Limbe, South-West Region of Cameroon.

Materials and Methods

Study design and settings

This study was a hospital based cross sectional study conducted from April to June 2025, at Limbe Regional Hospital (LRH) located in the South West Region of Cameroon. The Limbe Health District (LHD) located in the coastal region of Cameroon is between mount Cameroon to the North and the Atlantic Ocean to the South; and is made up of eight health areas which include: Bota, Mabeta, Idenau, Bojongo, Sea port, Moliwe, Batoke and Zone ∥. Heavy annual rain falls, added to intensive irrigation of this area and surroundings provides suitable breeding sites for malaria vectors, justifying its endemicity.

Study population and sampling

Pregnant women within the age range of 18 to 45 years who attended the antenatal care at LRH within the study period were consecutively enrolled to the study. The sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula.

For a z-value of 1.96, the standard normal variate at 95% confidence level, error margin of 5% (e), and a prevalence of 7.7% [11], a minimum sample size of 109 participants was required, however, up to 129 women were selected.

Ethical consideration

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea. An administrative authorization was obtained from the Regional Delegation of Public Health, South-West Region (Ref: 329/MPH/SWR/RDPH/RHL/DO/05/2025). Written consent was obtained from every participant before enrollment. Participants were informed about the benefits of the study and could withdraw at any point in time.

Laboratory methods

Microscopy for malaria diagnosis

Microscopy was used to determine the presence of malaria parasites, identify species, and estimate parasite density. Blood samples (4 to 5 mL) were collected in EDTA tubes. Thick blood films were made and air dried. Thereafter, the slides were stained with Giemsa 1:10 (for 10-15 minutes) and washed under running tap water and air-dried. A drop of immersion oil was placed on each slide, which was then read under a light microscope with a 100X objective. At least 200 microscopic fields were examined for the presence of parasites. The slides were counter-examined by skilled medical laboratory scientists. The malaria parasitemia was calculated using the formula: Number of parasites x 8000/Number of leucocytes counted. Hemoglobin concentrations (in g/dL) were determined as part of a complete blood count using the automated hematology analyzer (URIT 1000 PLUS).

Hemoglobin estimation

An automated haematology analyser (URIT 1000 PLUS) was used to measure haemoglobin concentration as part of a full blood count. Blood samples were mixed for three to five minutes before analysis. The haemoglobin (Hb) thresholds for diagnosing anaemia and severe anaemia were defined as Hb < 11.0 g/dL and Hb < 7.0 g/dL respectively [11].

Data collection

Data were collected using a questionnaire built using Epi info (Version 7.2.5.0) and exported to a printable format. The questionnaire was made of three sections: to collect data on the socio- demographic characteristics, obstetrics, Malaria and anemia related factors.

Data management and analysis

The Data obtained from the study participants were coded to ensure confidentiality and cleaned using Microsoft Excel 2016. The data was analyzed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 26.0 for windows. Categorical variables were presented using descriptive statistics. Logistic regression analysis was used to determine predictors of anemia in pregnancy. Odds ratio (OR) estimates and confidence interval (95% CI) with p values <0.05 were considered to be statistically significant.

Results

Socio-demographic characteristics of the study participants

A total of 129 pregnant women were recruited for this study. Their mean age was 29.4±5.4 years (Table 1), and most of them (n= 70, 54.3%), were within the age group of 26-29 years. Regarding level of education, less than half of the participants 53 (41.1%) had a secondary level of education. Majority, 98 (76%) were self–employed and 77 (59.7%) lived in Urban areas.

Table 1: Socio-demographic characteristics of pregnant women.

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency (N=129) |

Percentage % |

|

Age range (years) |

18-25 |

37 |

28.7 |

|

26-29 |

70 |

54.3 |

|

|

30-39 |

14 |

10.8 |

|

|

≥40 |

8 |

6.2 |

|

|

Level of education |

No formal education |

17 |

13.2 |

|

Primary |

30 |

23.3 |

|

|

Secondary |

53 |

41.1 |

|

|

Tertiary |

29 |

22.5 |

|

|

Occupation |

Employed |

5 |

3.9 |

|

Self-employed |

98 |

76 |

|

|

Unemployed |

26 |

20.2 |

|

|

Residence |

Rural |

52 |

40.3 |

|

Urban |

77 |

59.7 |

Obstetric factors of the study participants

Table 2 shows the obstetric characteristics of the participants. Almost half of the participants, 63 (48.8%), had a party from 1 to 2. Less than half of them, 54 (41.9%) had 2 to 3 previous pregnancies. More than half of the participants, 90 (69.8%), had no history of miscarriage or stillbirth. A greater proportion of the pregnant women, 85 (65.9%) were in their second trimester. The mean hemoglobin (Hb) concentration was 10.91 ± 1.31 g/dL.

Table 2: Obstetric factors of the study participants.

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency (N=129 |

Percentage % |

|

Parity |

01-02 |

63 |

48.8 |

|

03-04 |

32 |

24.8 |

|

|

≥5 |

34 |

26.4 |

|

|

Gravidity |

1 |

37 |

28.7 |

|

02-Mar |

54 |

41.9 |

|

|

≥4 |

38 |

29.5 |

|

|

Miscarriage or stillbirth |

No |

90 |

69.8 |

|

Yes |

39 |

30.2 |

|

|

Current trimester |

First |

44 |

34.1 |

|

Second |

85 |

65.9 |

|

|

Hematological parameter |

Hb (g/dL) |

10.91±1.31 |

|

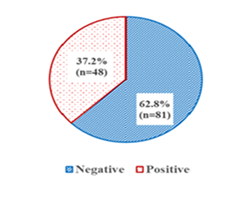

Prevalence of malaria and anaemia amongst pregnant women

Out of the 129 pregnant women that were sampled for this study, 48 had malaria parasitemia resulting in a malaria prevalence of 37.21% (95%CI: 28.87;45.55) (Figure 1). In the same line, the prevalence of anaemia (n=39 cases) was found to be 30.23% (95%CI: 22.31;38.16).

Distribution of Study Variables Related to Malaria and Anemia in Pregnancy

Most of the participants (85; 65.9 %) reported not to have been using insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and 55 (42.6%) have been living in high mosquito breeding areas. Regarding exposure to mosquitoes, 46 (35.7%) indicated that sometimes they could see mosquitoes in their vicinities. A majority of the participants (113; 87.6%) ate iron rich foods showing positive nutritional behaviour. In general, antenatal care attendance was good, 82;63.6% had been attending regularly. Meanwhile, 7% had never received antenatal care. It is particularly interesting that 73 (56.6%) of the participants did not take any precautions to prevent mosquito bites (Table 3).

Table 3: Distribution of Study Variables Related to Malaria and Anemia in Pregnancy.

|

Variable |

Category |

Frequency |

Percentage (%) |

|

Use of insecticide treated nets |

No |

85 |

65.9 |

|

Yes |

44 |

34.1 |

|

|

Live in high mosquito breeding area |

No |

74 |

57.4 |

|

Yes |

55 |

42.6 |

|

|

Mosquitoes around home |

No |

48 |

37.2 |

|

Sometimes |

46 |

35.7 |

|

|

Yes |

35 |

27.1 |

|

|

Consumption of iron rich foods |

No |

16 |

12.4 |

|

Yes |

113 |

87.6 |

|

|

ANC visit |

Never |

9 |

7 |

|

Occasionally |

38 |

29.5 |

|

|

Regularly |

82 |

63.6 |

|

|

Take measures to avoid mosquito bites |

No |

73 |

56.6 |

|

Yes |

56 |

43.4 |

Factors associated with malaria in pregnancy

Chi-square analysis identified several factors significantly associated with malaria (Table 4). Educational level, and history of miscarriage/stillbirth showed a strong association with malaria (p< 0.05). Table 5 shows a logistic regression model to identify the factors associated with malaria in pregnancy. After adjusting for confounders, the location of participant’s residence was found to be a significant predictor, with those living in the rural areas having higher odds of being positive for malaria than those in the urban areas (aOR = 7.769, 95% CI: 3.653-19.481, p=0.001).

Table 4: Factors associated with malaria prevalence (bivariate analysis).

|

Malaria |

|||||

|

Variable |

Categories |

Negative (%) |

Positive (%) |

χ² |

p-value |

|

Level Education |

No formal education |

3 (17.6) |

14 (82.4) |

25.227 |

<0.001 |

|

Primary |

27 (90.0) |

3 (10.0) |

|||

|

Secondary |

31 (58.5) |

22 (41.5) |

|||

|

Tertiary |

20 (69.0) |

9 (31.0) |

|||

|

Residence |

Rural |

5(9.6) |

47(90.4) |

105.433 |

<0.001 |

|

Urban |

76(98.7) |

1(1.3) |

|||

|

Miscarriage/Stillbirth |

No |

51 (56.7) |

39 (43.3) |

4.779 |

0.029 |

|

Yes |

30 (76.9) |

9 (23.1) |

|||

|

Insecticide-Treated Net use |

No |

53 (62.4) |

32 (37.6) |

0.021 |

0.886 |

|

Yes |

28 (63.6) |

16 (36.4) |

|||

|

Live in high mosquito breeding area |

No |

48 (64.9) |

26 (35.1) |

0.322 |

0.572 |

|

Yes |

33 (60.0) |

22 (40.0) |

|||

|

Mosquito Presence |

No |

29 (60.4) |

19 (39.6) |

2.776 |

0.253 |

|

Sometimes |

33 (71.7) |

13 (28.3) |

|||

|

Yes |

19 (54.3) |

16 (45.7) |

|||

|

ANC Attendance |

Never |

6 (66.7) |

3 (33.3) |

0.897 |

0.639 |

|

Occasionally |

26 (68.4) |

12 (31.6) |

|||

|

Regularly |

49 (59.8) |

33 (40.2) |

|||

|

Iron-Rich Food Consumption |

No |

11 (68.8) |

5 (31.3) |

0.278 |

0.598 |

|

Yes |

70 (61.9) |

43 (38.1) |

|||

Table 5: Predictors of malaria prevalence (multiivariate analysis).

|

95%CI |

|||||

|

Variable |

Category |

aOR |

Lower |

Upper |

p-value |

|

Insecticide treated use |

No |

1.607 |

0.282 |

9.15 |

0.593 |

|

Yes |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

Live in high mosquito breeding area |

No |

0.618 |

0.187 |

5.533 |

0.983 |

|

Yes |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

Residence |

Rural |

7.769 |

3.653 |

19.481 |

0.001 |

|

Urban |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

|

Factors associated with anemia in pregnancy

Chi-square analysis identified several factors significantly associated with anemia (Table 6). Educational level, residence, history of miscarriage/stillbirth and number of ANC visits showed a strong association with anemia (p<0.05). Table 7 shows a logistic regression model to identify the factors associated with anemia in pregnancy. After adjusting for confounders pregnant women with a history of miscarriage had higher odds of anemia when compared to those without (aOR=3.343, 95% CI:1.112-10.045, p=0.032). It was found that non-use of insecticide-treated nets was linked to 2.5 times the odds of anemia compared to those who use them (aOR=2.496, 95% CI:1.065-5.846, p=0.035). Those who rarely attended ANC also had 3.6 higher odds of being anemic relative to those who attended regularly (aOR=3.56, 95%CI:1.095-11.575, p=0.035).

Table 6: Factors associated with anaemia (bivariate analysis).

|

Anemia |

|||||

|

Variable |

Categories |

Absent (%) |

Present (%) |

χ² |

p-value |

|

Education Level |

No formal education |

9 (52.9) |

8 (47.1) |

9.413 |

0.024 |

|

Primary |

25 (83.3) |

5 (16.7) |

|||

|

Secondary |

32 (60.4) |

21 (39.6) |

|||

|

Tertiary |

24 (82.8) |

5 (17.2) |

|||

|

Occupation |

Employed |

4 (80.0) |

1 (20.0) |

1.211 |

0.546 |

|

Self-employed |

70 (71.4) |

28 (28.6) |

|||

|

Unemployed |

16 (61.5) |

10 (38.5) |

|||

|

Residence |

Rural |

34 (65.4) |

18 (34.6) |

0.793 |

0.373 |

|

Urban |

56 (72.7) |

21 (27.3) |

|||

|

Parity |

≥5 |

26 (76.5) |

8 (23.5) |

1.027 |

0.598 |

|

03-04 |

22 (68.8) |

10 (31.3) |

|||

|

01-02 |

42 (66.7) |

21 (33.3) |

|||

|

Gravidity |

≥4 |

27 (71.1) |

11 (28.9) |

0.606 |

0.739 |

|

02-Mar |

39 (72.2) |

15 (27.8) |

|||

|

1 |

24 (64.9) |

13 (35.1) |

|||

|

Miscarriage/Stillbirth |

No |

56 (62.2) |

34 (37.8) |

8.035 |

0.005 |

|

Yes |

34 (87.2) |

5 (12.8) |

|||

|

Trimester |

First |

29 (65.9) |

15 (34.1) |

0.471 |

0.492 |

|

Second |

61 (71.8) |

24 (28.2) |

|||

|

Insecticide-Treated Net use |

No |

65 (76.5) |

20 (23.5) |

5.309 |

0.021 |

|

Yes |

25 (56.8) |

19 (43.2) |

|||

|

Live in high mosquito breeding area |

No |

47 (63.5) |

27 (36.5) |

||

|

Yes |

43 (78.2) |

12 (21.8) |

|||

|

Mosquito Presence |

No |

33 (68.8) |

15 (31.3) |

1.378 |

0.502 |

|

Sometimes |

30 (65.2) |

16 (34.8) |

|||

|

Yes |

27 (77.1) |

8 (22.9) |

|||

|

Iron-Rich Food Consumption |

No |

10 (62.5) |

6 (37.5) |

0.457 |

0.499 |

|

Yes |

80 (70.8) |

33 (29.2) |

|||

|

ANC Attendance |

Never |

4 (44.4) |

5 (55.6) |

||

|

Occasionally |

34 (89.5) |

4 (10.5) |

|||

|

Regularly |

52 (63.4) |

30 (36.6) |

|||

|

Malaria prevalence |

Negative |

59 (72.8) |

22 (27.2) |

||

|

Positive |

31 (64.6) |

17 (34.4) |

|||

Table 7: Predictors of anaemia in pregnancy (multivariate analysis).

|

95%CI |

|||||

|

Variable |

Category |

aOR |

Lower |

Upper |

p-value |

|

Miscarriage or stillbirth |

Yes |

3.343 |

1.112 |

10.045 |

0.032 |

|

No |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

Insecticide treated net use |

No |

2.496 |

1.065 |

5.846 |

0.035 |

|

Yes |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

Live in high mosquito breeding area |

No |

0.458 |

0.19 |

1.103 |

0.082 |

|

Yes |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

|

|

ANC visit |

Never |

1.41 |

0.921 |

1.728 |

0.224 |

|

Occasionally |

3.56 |

1.095 |

11.575 |

0.035 |

|

|

Regularly |

1 |

. |

. |

. |

|

Discussion

This study had a malaria prevalence of 37.2% among 129 pregnant women receiving antenatal care (ANC) at Limbe Regional Hospital in the South West region of Cameroon. This is a higher prevalence compared to other findings that have been reported in other studies in Cameroon and the sub-Saharan Africa region at large. An example is a study that was done at the Bamenda Regional Hospital, where the prevalence of malaria in pregnant women attending ANC was found to be 18.4% [13]. In a similar study in Douala, Cameroon, a prevalence of 3.5 % and 4.3 % was recorded with rapid diagnostic tests and microscopy, respectively [14]. The difference in the prevalence could be explained by environmental conditions of the Limbe area, which include protection of its coastline and dense vegetation, which can favor the breeding and spreading of mosquitos more than Douala [15]. In comparison, other studies in other countries of sub-Saharan Africa reported the prevalence of malaria during pregnancy to vary. As an example, the prevalence in a multicenters study in Ghana was estimated at 8.9% [16], and a prevalence of 12.9% was determined in a study in Kenya with asymptomatic pregnant women [17]. The finding of higher prevalence in Limbe indicates the necessity of specific malaria control measures in this area, especially due to the life-threatening effects of malaria during pregnancy. According to the study, malaria was a predictable illness based on place of residence where the pregnant women in rural residence had higher chances of malaria infection than those in urban areas. This result can be compared to other studies conducted in Cameroon and other areas with malarial occurrences. In a study conducted in Bamenda, in Cameroon, living in rural places predisposed people to malaria with an odds ratio of 4.93 [13]. Likewise, in a study in Mali, the risk of malaria in pregnancy was associated with residing in the rural location as opposed to the urban setting raising the risk by 2.49 times [18]. Compared to other regions (urban areas), rural communities face a shortage of medical services, lack the use of preventive tools, such as insect-repellent nets (ITNs), and environmental factors that promote mosquito growth [19]. These are probably the reasons why the burden of malaria is high in the rural areas. History of miscarriage/ still birth, non-use of ITNs, and irregular ANC visits were identified as predictors of anemia in pregnancy. Risk of anemia has increased in persons with miscarriage or still-birth. This was in line with a study conducted in Ethiopia were obstetric complications such as history of miscarriage was linked to the risk of having anemia because of chronic blood loss and nutritional deficiency [20]. Failure to use ITNs indicated a 2.5-fold higher likelihood of anemia, and this finding is in line with past studies that implicate malaria infection as a reason for anemia during pregnancy. A research conducted in the Buea Health District in Cameroon also indicated that malaria contributed immensely to anemia, whereby 95.6% of the anemic expectant women had been diagnosed with malaria [21]. The use of ITNs limits the spread of malaria because it prevents the act of mosquito bites hence the chances of developing malaria-related anemia through the process of hemolysis and the decreased production of red blood cells [21]. This protective effect of the ITNs gives an indication that, more distribution and awareness of the regular usage of ITNs should be done among the antenatal women in the rural areas. Irregular ANC visits was also found to be linked to greater likelihood of anemia and this can be attributed to the fact that ANC visit presented an opportunity of early detection and treatment of anemia and malaria. This was not surprising, as holistic health training offered during ANC improves the overall health of expectant mothers. A study in Ghana stressed that the early and frequent Ante-Natal Care increased the detection and resolution of anemia, which decreased its prevalence and manifestations [16]. Strategies to encourage early initiation and regular ANC clinic attendance are especially important as the proportions of care that ANC covers in Cameroon are not optimal in all areas. ANC uptake can be alleviated using mobile clinics and community-based health education programs especially in rural settlements where transportation to healthcare facilities is a problem. The administration of community based IPTp will also help cover individuals who cannot access ANC facilities in the community.

Conclusion

The prevalences of malaria and anaemia among pregnant women accessing antenatal care at the Limbe Regional Hospital in the South West Region of Cameroon were found to be high (37.2%, and 30.2% respectively) illustrating a major area of public health concern in this region. Living in rural areas was identified as the main risk factor of malaria, which implies that interventions should focus on addressing the environmental and access-related obstacles in the rural community. Also, history of miscarriage/still birth, not using insecticide-treated nets (ITNs), and irregular antenatal care (ANC) visits were significantly related to anemia. These results underline the importance of the consistent ITN use and regular ANC visits in the prevention of anemia, especially in women with a history of obstetric complications. Social-public health interventions should aim to increase access to ITNs and implement intermittent preventive treatment in rural settings, and to encourage early and frequent ANC follow-up to minimize the malaria and anemia burden in pregnancy.

Acknowledgement

The authors are grateful to the administration of the Limbe regional Hospital and mainly the ANC unit for allocating a workspace to the investigators for data collection. We also thank the pregnant women who visited the unit during the period of data collection.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Funding

Expenditure covered in this study was supported by the investigator’s own fund. No external source of funding was secured for the study.

Authors’ contribution

BNA: Study protocol, conducted data collection, laboratory analysis, manuscript drafting

NFT: supervised data collection and slide reading, manuscript drafting

SME: supervised data collection and haemoglobin analysis, manuscript drafting

TP: design data collection tools, create the database, conduct data analysis, manuscript drafting

WN: conducted data collection, laboratory analysis, manuscript drafting

ANL: reviewed the study protocol, and proofread the manuscript, manuscript drafting

AJN: contributed to the study design, supervised data collection and analysis, revised the manuscript

All authors read and approved the final version of manuscript.

References

- Uneke CJ. Impact of placental Plasmodium falciparum malaria on pregnancy and perinatal outcome in sub-Saharan Africa: II: effects of placental malaria on perinatal outcome; malaria and HIV. The Yale journal of biology and medicine 80 (2008): 95.

- Gontie GB, Wolde HF, Baraki AG. Prevalence and associated factors of malaria among pregnant women in Sherkole district, Benishangul Gumuz regional state, West Ethiopia. BMC Infectious Diseases 20 (2020): 573.

- Obeagu EI, Agreen FC. Anaemia among pregnant women: A review of African pregnant teenagers. J Pub. Health Nutri 6 (2023): 138

- Obeagu EI, Ezimah AC, Obeagu GU. Erythropoietin in the anaemias of pregnancy: a review. Int J Curr Res Chem Pharm Sci 3 (2016): 10-18.

- Obeagu EI, Adepoju OJ, Okafor CJ, et al. Assessment of Haematological Changes in Pregnant Women of Ido, Ondo State, Nigeria. J Res Med Dent Sci 9 (2021): 145-148.

- Obeagu EI, Obeagu GU. Sickle cell anaemia in pregnancy: a review. International Research in Medical and Health Sciences 6 (2023): 10-13.

- Jakheng SP, Obeagu EI. Seroprevalence of human immunodeficiency virus based on demographic and risk factors among pregnant women attending clinics in Zaria Metropolis, Nigeria. J Pub Health Nutri 5 (2022): 137.

- Marshall JS, Warrington R, Watson W, et al. An introduction to immunology and immunopathology. Allergy, Asthma & Clinical Immunology 14 (2018): 49.

- Obeagu EI, Ibeh NC, Nwobodo HA, et al. Haematological indices of malaria patients coinfected with HIV in Umuahia. Int. J. Curr. Res. Med. Sci 3 (2017): 100-104.

- Feeney ME. The immune response to malaria in utero. Immunological reviews 293 (2020): 216-229.

- Suryanarayana R, Chandrappa M, Santhuram AN, et al. Prospective study on prevalence of anemia of pregnant women and its outcome: A community based study. Journal of family medicine and primary care 6 (2017): 739.

- Ahadzie-Soglie A, Addai-Mensah O, Abaka-Yawson A, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of malaria and anaemia and the impact of preventive methods among pregnant women: A case study at the Akatsi South District in Ghana. PLoS One 17 (2022): e0271211.

- Mukala J, Mogere D, Kirira P, et al. Knowledge, attitude and practices on intermittent preventive treatment in pregnant women with malaria: a mixed method facility-based study in Western Kenya. Pan African Medical Journal 48 (2024).

- Kuete T, Essome H, Moche LB, et al. Prevalence, Associated Factors and Treatment Outcomes of Laboratory-confirmed Pregnancy Malaria at Antenatal Care in Three Healthcare Facilities of Douala, Cameroon. International Journal of Tropical Disease & Health 45 (2024): 105-116.

- Kimbi HK, Sumbele IU, Nweboh M, et al. Malaria and haematologic parameters of pupils at different altitudes along the slope of Mount Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Malaria journal 12 (2013): 193.

- Fondjo LA, Addai-Mensah O, Annani-Akollor ME, et al. A multicenter study of the prevalence and risk factors of malaria and anemia among pregnant women at first antenatal care visit in Ghana. PloS one 15 (2020): e0238077.

- Nyamu GW, Kihara JH, Oyugi EO, et al. Prevalence and risk factors associated with asymptomatic Plasmodium falciparum infection and anemia among pregnant women at the first antenatal care visit: a hospital based cross-sectional study in Kwale County, Kenya. PloS one 15 (2020): e0239578.

- Dicko A, Mantel C, Thera MA, et al. Risk factors for malaria infection and anemia for pregnant women in the Sahel area of Bandiagara, Mali. Acta Tropica 89 (2003): 17-23.

- Kimbi HK, Sumbele IU, Nweboh M, et al. Malaria and haematologic parameters of pupils at different altitudes along the slope of Mount Cameroon: a cross-sectional study. Malaria journal 12 (2013): 193.

- Gudeta TA, Regassa TM, Belay AS. Magnitude and factors associated with anemia among pregnant women attending antenatal care in Bench Maji, Keffa and Sheka zones of public hospitals, Southwest, Ethiopia, 2018: A cross-sectional study. PloS one 14 (2019): e0225148.

- Jugha VT, Anchang-Kimbi JK, Anchang JA, et al. Dietary diversity and its contribution in the etiology of maternal anemia in conflict hit Mount Cameroon area: a cross-sectional study. Frontiers in Nutrition 7 (2021): 625178.

Impact Factor: * 6.2

Impact Factor: * 6.2 Acceptance Rate: 76.33%

Acceptance Rate: 76.33%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks