Biomarkers and Diagnostic Criteria for Early Differentiation of Transfusion- Related Acute Lung Injury and Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload: A Systematic Review

Rana Ahmed1, Salis Aizaz Rasool2, Dhruba Dhar3, Istia Mumtahina Meem3, Shashwat Shetty1, Ahmad Abdurrahman Thaika4, Shahmeen Rasul5, Manahil Awan6, Shahzad Ahmad6*

1The Hillingdon Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, UK

2Dudley Group of NHS Foundation Trust, UK

3BGC Trust Medical College Hospital, Bangladesh

4Moseley Hall Hospital, UK

5Royal Free London NHS Foundation Trust, UK

6Liaquat National Hospital, Pakistan

*Corresponding Author: Shahzad Ahmad, Liaquat National Hospital, Pakistan

Received: 19 January 2026; Accepted: 27 January 2026; Published: 06 February 2026

Article Information

Citation: Rana Ahmed, Salis Aizaz Rasool, Dhruba Dhar, Istia Mumtahina Meem, Shashwat Shetty, Ahmad Abdurrahman Thaika, Shahmeen Rasul, Manahil Awan, Shahzad Ahmad. Biomarkers and Diagnostic Criteria for Early Differentiation of Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury and Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload: A Systematic Review. Journal of Surgery and Research. 9 (2026): 40-46.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Transfusion-related respiratory complications, including transfusionrelated acute lung injury (TRALI) and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), are major causes of morbidity and mortality in transfused patients. Differentiating these conditions is challenging due to overlapping clinical presentations but is critical for appropriate management. This systematic review synthesizes current evidence on biomarkers and diagnostic criteria to enable early and accurate differentiation of TRALI and TACO. A comprehensive literature search identified six studies examining cardiac biomarkers (BNP, NT-proBNP), endothelial injury markers (syndecan-1), and inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α). NTproBNP and syndecan-1 were consistently elevated in TACO, reflecting circulatory overload and glycocalyx disruption, whereas inflammatory cytokines were associated with TRALI, indicating immune-mediated capillary leak. Integrated approaches combining biomarkers with clinical assessment and imaging improved diagnostic accuracy, particularly in overlapping cases. Limitations include small sample sizes, single-center designs, and variability in biomarker thresholds. These findings support the use of a multimarker strategy to guide early differentiation, optimize targeted interventions, and reduce misclassification. Future research should focus on prospective validation of biomarker algorithms and their impact on patient outcomes.

Keywords

TRALI, TACO, Biomarkers, NT-proBNP, Syndecan-1, Cytokines

Article Details

Introduction

Transfusion-related respiratory complications represent a significant cause of transfusion-associated morbidity and mortality, particularly among critically ill and perioperative patients. Among these complications, transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) and transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO) are the two most clinically important entities, both presenting with acute respiratory distress shortly after blood transfusion. However, the underlying mechanisms, diagnostic criteria, and therapeutic approaches differ substantially, making timely differentiation essential for effective management and improved clinical outcomes. TRALI is defined as an acute non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema occurring within 6 hours of transfusion, characterized by hypoxemia (PaO2/FiO2 ≤ 300 mmHg or SpO2 < 90% on room air), bilateral pulmonary infiltrates on imaging, and absence of circulatory overload or left atrial hypertension [1]. It may occur in the absence of Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) risk factors (Type I TRALI) or in the presence of predisposing conditions without evidence of respiratory deterioration prior to transfusion (Type II TRALI) [2]. The pathophysiology is largely immune-mediated, involving donor-derived anti-HLA or anti-HNA antibodies, or non-immune two-hit inflammatory mechanisms leading to capillary leak and lung injury [3].

In contrast, TACO is characterized by hydrostatic (cardiogenic) pulmonary edema resulting from circulatory overload, typically occurring within 6-12 hours after transfusion [4]. Clinical diagnostic criteria include respiratory distress, positive fluid balance, elevated central venous or pulmonary capillary wedge pressures, radiographic pulmonary edema, and biochemical evidence of cardiac stress, most notably elevated brain natriuretic peptide (BNP) or N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP) [5]. TACO risk is increased in elderly patients and those with renal dysfunction, cardiac disease, or rapid/high-volume transfusion.Despite clear mechanistic differences, TRALI and TACO frequently overlap in clinical presentation, producing dyspnea, hypoxemia, and pulmonary infiltrates, often leading to misclassification [6]. This carries important clinical consequences: TRALI may require avoidance of further antibody-mediated exposure and escalation of ventilatory support, whereas TACO benefits from diuresis, fluid restriction, and cardiovascular optimization [7]. Diagnostic delays or inaccuracies can lead to increased ICU admissions, mechanical ventilation, prolonged hospitalization, and higher mortality.

The challenge of bedside differentiation has stimulated interest in biomarkers as adjunctive diagnostic tools. Biomarkers of endothelial injury and inflammation (e.g., IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α, RAGE, syndecan-1) have been proposed for TRALI, reflecting capillary leak and cytokine-driven injury, while biomarkers of cardiac volume overload (BNP, NT-proBNP) support the diagnosis of TACO [8]. Although several studies have evaluated biomarker performance individually or in combination, findings are variable and lack standardization across clinical settings. A comprehensive synthesis of their diagnostic accuracy, utility, and limitations is necessary to guide clinicians and support evidence-based practice.

The primary aim of this systematic review is to assess the current evidence on biomarkers and diagnostic criteria that enable early and accurate differentiation between TRALI and TACO. Specifically, this review evaluates the diagnostic performance and clinical utility of biochemical, clinical, radiographic, and hemodynamic markers reported in the literature. A secondary aim is to analyze the strengths and limitations of available diagnostic tools, identify gaps and inconsistencies in current diagnostic pathways, and propose an evidence-based framework to support bedside decision-making. Additionally, this review highlights implications for patient outcomes and outlines future research priorities relevant to transfusion medicine and critical care settings.

Methodology

Study design and Literature search

This systematic review was designed and conducted in accordance with the PRISMA 2020 guidelines [9]. A structured and comprehensive literature search was performed across PubMed/MEDLINE, Embase, Scopus, Web of Science, Google Scholar, and the Cochrane Library from 1 October 2025 to 2 December 2025. The search strategy incorporated a combination of controlled vocabulary terms (MeSH/Emtree) and free-text keywords related to “TRALI”, “TACO”, “transfusion-related acute lung injury”, “transfusion-associated circulatory overload”, “biomarkers”, “natriuretic peptides”, “BNP”, “NT-proBNP”, “inflammatory markers”, and “endothelial injury”. No initial language or publication status restrictions were applied; however, non-English full texts were excluded at screening if adequate translation resources were not available. The search strategy was supplemented by manual screening of reference lists from relevant articles and review papers to ensure completeness and capture additional eligible studies.

Eligibility criteria

The eligibility criteria for this systematic review were defined according to the PICO framework [10]. Population (P): human patients who developed pulmonary transfusion reactions following blood component transfusions; Intervention/Exposure (I): evaluation of biomarkers, clinical, radiological, or hemodynamic parameters to differentiate transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) from transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO); Comparator (C): either comparison between TRALI and TACO or assessment of diagnostic accuracy of biomarkers against established clinical criteria; Outcome (O): early and accurate differentiation between TRALI and TACO, including diagnostic performance, utility, and clinical applicability of biomarkers and diagnostic criteria. Studies were eligible if they involved adult or mixed adult-pediatric populations receiving any blood components, including red blood cells, plasma, platelets, or whole blood, and specifically evaluated TRALI, TACO, or both. Included studies reported extractable data on biomarkers (such as BNP, NT-proBNP, cytokines, or markers of endothelial injury), clinical or radiographic features, or hemodynamic measurements that could support differential diagnosis. Eligible study designs included prospective or retrospective cohort studies, case-control studies, cross-sectional studies, registry-based analyses, and narrative or systematic reviews that provided relevant diagnostic insights. Only peer-reviewed studies published in English were considered.Studies were excluded if they involved only animal or in vitro models, focused solely on other transfusion reactions without assessing TRALI or TACO, or lacked extractable biomarker or diagnostic data. Abstracts without full text, conference proceedings, editorials, commentaries, or non-English publications were also excluded. Duplicate publications were identified and only the most complete or recent version was retained. These criteria were designed to ensure inclusion of studies that directly inform the diagnostic differentiation of TRALI and TACO and support evidence-based recommendations for clinical practice.

Data extraction

Data extraction was performed independently and systematically using a predefined data collection framework. From each eligible study, we extracted information on study characteristics (author, year, country, study design, and setting), patient demographics, type of transfused blood components, diagnostic definitions applied for TRALI and TACO, and clinical, radiological, and hemodynamic criteria used for differentiation. Biomarker-related data included the type of biomarker investigated (e.g., BNP, NT-proBNP, cytokines, endothelial injury markers), timing of sample collection, analytical methods, and reported diagnostic performance metrics when available, including sensitivity, specificity, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), and proposed diagnostic thresholds. Additional data regarding outcomes, study limitations, and relevant contextual findings were also recorded to support qualitative synthesis. Any discrepancies in data extraction were resolved through discussion and consensus among the reviewers.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment was conducted to evaluate methodological rigor and potential sources of bias in the included studies. Observational cohort, case-control, and cross-sectional studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), which evaluates studies across three domains: selection of participants, comparability of study groups, and outcome assessment [11]. Narrative reviews contributing diagnostic or biomarker-related insights were evaluated using the Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (SANRA), which assesses six methodological criteria including justification of the article's importance, statement of aims, literature search quality, referencing, scientific reasoning, and appropriate presentation of data [12]. Studies were categorized as having low, moderate, or high risk of bias according to their respective scoring systems. Quality ratings were not used as exclusion criteria; instead, they informed the interpretation of findings and the strength of evidence presented in the final synthesis.

Result

Study selection process

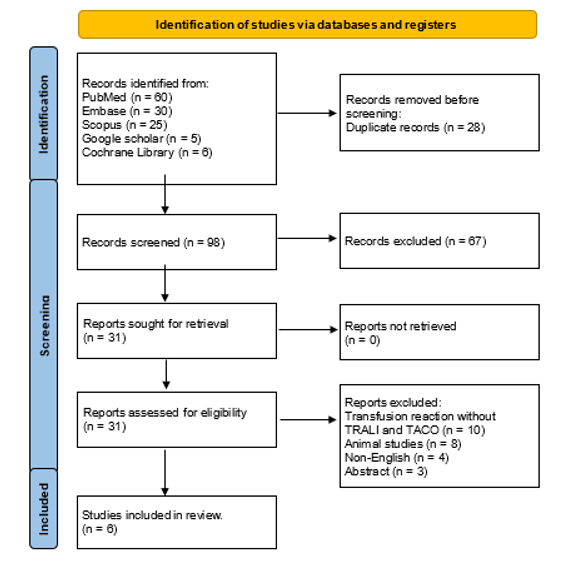

A total of 126 articles were identified through database searches (PubMed, Embase, Scopus, Google Scholar, and Cochrane Library). After removing 28 duplicates, 98 articles remained for title and abstract screening. Of these, 67 articles were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria, primarily due to non-relevance to TRALI or TACO, absence of biomarker or diagnostic data, or being reviews/editorials without extractable information. This left 31 full-text articles for detailed assessment. During full-text review, 25 studies were excluded for the following reasons: studies involving only animal or in vitro models (n=8), studies focused exclusively on other transfusion reactions without TRALI/TACO evaluation (n=10), non-English full texts (n=4), and abstracts or conference proceedings without complete data (n=3). Consequently, 6 studies met all eligibility criteria and were included in the final qualitative synthesis. The study selection process is summarized as PRISMA flow diagram in figure 1.

Characteristics of the Selected Studies

Table 1 shows six studies published between 2008 and 2023, comprising prospective observational cohorts, a retrospective cohort, and a narrative review, with a total of 567 patients across clinical studies. Li et al. assessed BNP and NT-proBNP within 24 hours post-transfusion in critically ill adults with TRALI (n=34), possible TRALI (n=31), and TACO (n=50), finding higher NT-proBNP in TACO but with overlapping values limiting standalone diagnostic use [13]. Tobian et al. (2008) reported markedly elevated pre- and post-transfusion NT-proBNP in TACO cases compared to transfused controls, supporting its diagnostic role in circulatory overload [14]. Bulle et al. (2023)prospectively measured NT-proBNP, syndecan-1, IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α in 64 critically ill adults receiving single-unit RBC transfusions, finding NT-proBNP and syndecan-1 significantly increased in TACO, while cytokines were less discriminatory [15]. Semple et al. (2019) provided a narrative review summarizing BNP, NT-proBNP, and inflammatory cytokines, emphasizing a combined approach of biomarkers, clinical features, and imaging to differentiate TRALI from TACO [16]. Roubinian et al. (2020), using the REDS-III retrospective cohort, demonstrated that NT-proBNP measured within 24 hours improved classification of TACO, TRALI, and overlap cases when combined with clinical predictors [17]. Looney et al. (2014) conducted a multicenter prospective study in patients with TRALI and possible TRALI, showing early IL-6 and IL-8 elevation correlated with greater disease severity, longer ICU stay, fewer ventilator-free days, and higher mortality [18]. Collectively, these studies indicate that NT-proBNP and syndecan-1 are reliable markers for TACO, whereas inflammatory cytokines reflect TRALI, highlighting the need for an integrated diagnostic approach combining biomarkers with clinical and radiographic assessment.

Table 1: Characteristics of the selected studies.

Legends

BNP = B-type natriuretic peptide

NT-proBNP = N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide

TRALI = Transfusion-related acute lung injury

TACO = Transfusion-associated circulatory overload

RBC = Red blood cells

IL = Interleukin

TNF-α = Tumor necrosis factor-alpha

ICU = Intensive care unit

N/A = Not applicable

Risk of Bias Assessment

Table 2 shows included studies were assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for cohort and case-control studies and SANRA for the narrative review. Li et al. and Tobian et al. scored 6/9 (moderate risk) due to single-center design, small sample size, and potential selection or classification bias [13,14]. Bulle et al. scored 6/9 (low-moderate risk) with strong internal validity from serial biomarker measurements but limited generalizability [15]. Semple et al. scored 9/12 (moderate risk) due to lack of systematic search and formal inclusion criteria [16]. Roubinian et al. scored 7/9 (low-moderate risk) with a large multicenter dataset but small TRALI subgroup [17]. Looney et al. scored 8/9 (low risk) owing to robust multicenter design, early biomarker measurement, and standardized outcomes [18].

|

Study |

Study Design |

Risk of Bias Tool |

Score |

Risk of Bias Rating |

Justification |

|

Li et al., 2009 [13] |

Prospective observational cohort |

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) |

6/9 |

Moderate risk of bias |

Well-defined cohorts and objective measurement of BNP and NT-proBNP; however, single-center design and overlap in biomarker values between TRALI and TACO groups may contribute to classification bias. |

|

Tobian et al., 2008 [14] |

Case-control |

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) |

6/9 |

Moderate risk of bias |

Clear case and control definitions with standardized NT-proBNP assays; limited sample size and retrospective identification of cases increase potential selection bias. |

|

Bulle et al., 2023 [15] |

Prospective cohort |

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) |

6/9 |

Low-moderate risk of bias |

Prospective design with serial biomarker measurements strengthens internal validity; generalizability limited by modest sample size and restriction to single-unit transfusions. |

|

Semple et al., 2019 [16] |

Narrative expert review |

SANRA (0-12) |

9/12 |

Moderate risk of bias |

Clearly stated clinical rationale and expert synthesis with strong pathophysiological grounding; however, absence of a systematic literature search, predefined inclusion criteria, and formal study selection process introduces potential selection and reporting bias. |

|

Roubinian et al., 2020 [17] |

Retrospective cohort (REDS-III) |

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) |

7/9 |

Low-moderate risk of bias |

Large multicenter dataset improves external validity; retrospective design and relatively small TRALI subgroup increase risk of residual confounding and misclassification. |

|

Looney et al., 2014 |

Multicenter prospective cohort |

Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) |

8/9 |

Low risk of bias |

Robust multicenter prospective design with standardized case adjudication, early biomarker measurement, and clearly defined clinical outcomes minimizes selection and measurement bias. |

Table 2: Risk of Bias Assessment.

Legends

NOS: Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (score range 0–9)

- • 0-3: High risk of bias

- • 4-6: Moderate risk of bias

- • 7-9: Low risk of bias

SANRA: Scale for the Assessment of Narrative Review Articles (score range 0-12)

- • 0-4: High risk of bias

- • 5-8: Moderate risk of bias

- • 9-12: Low risk of bias

TRALI: Transfusion-related acute lung injury

TACO: Transfusion-associated circulatory overload

Discussion

This systematic review provides a comprehensive synthesis of current evidence on biomarkers and diagnostic criteria for differentiating transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI) from transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO). Across studies, our analysis reveals distinct biomarker patterns that can support early and accurate diagnosis, addressing a critical gap in transfusion medicine.Cardiac biomarkers, particularly NT-proBNP and BNP, consistently emerged as reliable indicators of TACO. Li et al. (2009) demonstrated significantly higher NT-proBNP levels in TACO compared to TRALI or possible TRALI, although overlapping values limited standalone diagnostic use [13]. Tobian et al. (2008) similarly reported elevated pre- and post-transfusion NT-proBNP in TACO patients, supporting its role as an early marker of circulatory overload [14]. These studies highlight that NT-proBNP is highly sensitive for identifying volume overload but should be interpreted alongside clinical and radiographic findings.

Endothelial injury markers, notably syndecan-1, offer additional discriminatory value. Bulle et al. (2023) reported elevated syndecan-1 in TACO, reflecting glycocalyx disruption from fluid overload, and found that combining syndecan-1 with NT-proBNP improved differentiation from TRALI [15]. This underscores the utility of assessing endothelial injury in conjunction with cardiac biomarkers to enhance diagnostic precision.Inflammatory cytokines, including IL-6, IL-8, and TNF-α, were strongly associated with TRALI. Looney et al. (2014) demonstrated early cytokine elevation correlated with increased disease severity, longer ICU stay, fewer ventilator-free days, and higher mortality [18]. Bulle et al. (2023) also observed modest cytokine increases in TRALI but noted limited specificity for differentiation from TACO [15]. These findings reflect the immune-mediated, two-hit pathophysiology of TRALI, where cytokine-driven capillary leak contributes to pulmonary edema. Integrated biomarker approaches, as emphasized by Semple et al. (2019) and Roubinian et al. (2020), enhance diagnostic accuracy [16][17]. NT-proBNP and syndecan-1 reliably identify TACO, while inflammatory cytokines indicate TRALI, particularly when combined with clinical assessment, imaging, and hemodynamic measurements. Roubinian et al. demonstrated that including NT-proBNP in predictive models improved classification of overlapping cases, highlighting the importance of multimodal evaluation [17].

Our findings reinforce prior observations regarding the complementary roles of cardiac and inflammatory biomarkers in transfusion-related pulmonary complications. Unlike earlier studies that often focused on single markers or small cohorts, our review synthesizes observational and narrative evidence, providing a comprehensive framework for clinical application. The emphasis on combined biomarker assessment aligns with emerging consensus in transfusion medicine, advocating integrated diagnostic algorithms to reduce misclassification and guide management.

Several limitations merit consideration. Most studies were single-center or had small sample sizes, limiting generalizability. Variability in biomarker thresholds and timing of measurements complicates direct comparisons. Overlapping NT-proBNP values between TRALI and TACO cases may reduce specificity, particularly in patients with pre-existing cardiac or renal dysfunction. Pediatric populations and high-risk comorbid groups remain underrepresented, and narrative reviews included in the synthesis are inherently prone to selection and reporting bias.

These findings have immediate implications for clinical practice. An integrated diagnostic strategy combining NT-proBNP, syndecan-1, inflammatory cytokines, and clinical assessment can guide early differentiation of TACO and TRALI, enabling targeted interventions such as diuresis for TACO or supportive care for TRALI. Future research should focus on prospective, multicenter validation of biomarker thresholds, development of weighted diagnostic algorithms, and evaluation of their impact on patient-centered outcomes. Emerging biomarkers of endothelial and immune activation may further refine TRALI specificity and support personalized management strategies.We propose that a multimarker algorithm, incorporating NT-proBNP, syndecan-1, and cytokine profiles, could enhance early differentiation between TACO and TRALI. Additionally, serial biomarker measurements within the first 12-24 hours post-transfusion may provide dynamic insights into disease progression and facilitate identification of overlap syndromes, warranting early intervention

Conclusion

This systematic review demonstrates that NT-proBNP and BNP are reliable biomarkers for TACO, while inflammatory cytokines (IL-6, IL-8, TNF-α) indicate TRALI. Syndecan-1 enhances differentiation by reflecting endothelial injury. Integrated assessment combining biomarkers, clinical features, imaging, and hemodynamics improves early diagnostic accuracy. Early differentiation enables targeted interventions like diuresis for TACO and supportive care for TRALI, reducing morbidity and ICU stay. Limitations include variable biomarker thresholds, overlapping values, and small cohort sizes. Future research should validate multimarker algorithms and assess serial biomarker monitoring to optimize patient outcomes.

Registration

This systematic review was conducted in adherence to the PRISMA 2020 guidelines. No separate registry number was assigned.

Acknowledgements

The authors have no acknowledgements to declare.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of interest and source of funding

Each author, their immediate family, and any research foundation with which they are affiliated did not receive any financial payments or other benefits from any commercial entity related to the subject of this article.

References

- Kuriri FA. Transfusion-related acute lung injury (TRALI): Current understanding, challenges, and future directions. Saudi Med J 46 (2025): 865-877.

- Vlaar APJ, Kleinman S. An Update of the Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury (TRALI): A Proposed Modified Definition and Classification Scheme Definition. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus 36 (2020): 556-558.

- Cho MS, Modi P, Sharma S. Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury. [Updated 2023 Sep 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing (2025).

- Bosboom JJ, Klanderman RB, Migdady Y, et al. Transfusion-Associated Circulatory Overload: A Clinical Perspective. Transfus Med Rev 33 (2019): 69-77.

- Narick C, Triulzi DJ, Yazer MH. Transfusion-associated circulatory overload after plasma transfusion. Transfusion 52 (2012): 160-165.

- Leary H, Webert KE, Heddle NM. Investigation of Acute Transfusion Reactions. Practical Transfusion Medicine 27 (2022): 77-90.

- Yaroshetskiy, Andrey S, Zhigulin G. TRALI and TACO syndrome. Pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment: a review. Annals of Critical Care 12 (2024): 47-57.

- Lowack J, Vlaar AP, Klanderman RB, et al. Pulmonary transfusion reactions as an immunological spectrum disorder. Current Opinion in Immunology 98 (2026): 102689.

- Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 29 (2021): 372.

- Brown D. A Review of the PubMed PICO Tool: Using Evidence-Based Practice in Health Education. Health Promot Pract 21 (2020): 496-498.

- Lo CK, Mertz D, Loeb M. Newcastle-Ottawa Scale: comparing reviewers' to authors' assessments. BMC Med Res Methodol 14 (2014): 45.

- Baethge C, Goldbeck-Wood S, Mertens S. SANRA-a scale for the quality assessment of narrative review articles. Res Integr Peer Rev 26 (2019): 5.

- Li G, Daniels CE, Kojicic M, et al. The accuracy of natriuretic peptides (brain natriuretic peptide and N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic) in the differentiation between transfusion-related acute lung injury and transfusion-related circulatory overload in the critically ill. Transfusion 49 (2009): 13-20.

- Tobian AA, Sokoll LJ, Tisch DJ, et al. N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide is a useful diagnostic marker for transfusion-associated circulatory overload. Transfusion 48 (2008): 1143-1150.

- Bulle EB, Blanken B, Klanderman RB, et al. Exploring NT-proBNP, syndecan-1, and cytokines as biomarkers for transfusion-associated circulatory overload in a critically ill patient population receiving a single-unit red blood cell transfusion. Transfusion 63 (2023): 2052-2060.

- Semple JW, Rebetz J, Kapur R. Transfusion-associated circulatory overload and transfusion-related acute lung injury. Blood 133 (2019): 1840-1853.

- Roubinian NH, Chowdhury D, Hendrickson JE, et al. NHLBI Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-III (REDS-III). NT-proBNP levels in the identification and classification of pulmonary transfusion reactions. Transfusion 60 (2020): 2548-2556.

- Looney MR, Roubinian, N, Gajic O, et al. Prospective Study on the Clinical Course and Outcomes in Transfusion-Related Acute Lung Injury. Critical Care Medicine 42 (2014): 1676-1687.

Impact Factor: * 4.2

Impact Factor: * 4.2 Acceptance Rate: 72.62%

Acceptance Rate: 72.62%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks