The Growing Value of Multicentre, Prospective, Real-world Data: Early- Outcomes of 1000 Patients with the Avalus Aortic Valve

Lennart Vanglabeke*1, Tom Verbelen*1, Jean-Christian Roussel2, Christian Lildal Carranza3, Lenard Conradi4, Koen Cathenis5, Giovanni Troise6, Julien Guihaire7, Juan Bustamante-Munguira8, Davide Pacini9, Paolo Centofanti10, Nicolas Doll11, Rafael Llorens12, Yanai Ben-Gal13, Francesco Musumeci14, Tine Philipsen15, Laurent de Kerchove16, Roberto Lorusso17, Alberto Giovanni Tripodi18, Alberto Canziani19, Antti Valtola20, Bart Meuris1

1Department of Cardiac Surgery, University Hospitals Leuven & Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, KU Leuven-University of Leuven, Leuven Belgium

2Department of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery, CHU Nantes, Nantes, France

3Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Rigshospitalet København Ø, Copenhagen, Denmark

4Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Universitäres Herz- und Gefäßzentrum Hamburg, Hamburg, Germany

5Department of Cardiac Surgery, AZ Maria Middelares Gent, Gent, Belgium

6Department of Cardiac Surgery, Fondazione Poliambulanza Brescia, Brescia, Italy

7Department of Cardiac Surgery and Transplantation, Hôpital Marie Lannelongue, Groupe Hospitalier Paris Saint-Joseph, Université Paris Saclay, France

8Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Hospital clinico de Valladolid, Valladolid, Spain

9Department of Cardiac Surgery, Osp. S.Orsola Malpighi-Bologna, Bologna, Italy

10Department of Cardiac Surgery, A. O. Ordine Mauriziano-Torino, Torino, Italy

11Department of Cardiac Surgery, Schüchtermann-Klinik, Bad Rothenfelde, Germany

12Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Hospital Rambla, Tenerife, Spain

13Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Tel Aviv Medical Center, Tel Aviv, Israel

14Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, San Camillo Hospital Roma, Roma, Italy

15Department of Cardiac Surgery, UZ Gent, Gent, Belgium

16Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, UCL St-Luc-Bruxelles, Bruxelles, Belgium

17Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, UMC Maastricht, Maastricht, the Netherlands & Cardiovascular Research Institute Maastricht (CARIM), Maastricht, the Netherlands

18Department of Cardiovascular Surgery, Villa Maria Cecilia-Cotignola, Cotignola, Italy

19Department of Cardiac Surgery, Policlinico San Donato S.P.A -San Donato Milanese, Milan, Italy

20Department of Cardiac Surgery, Kuopio University Hospital, Kuopio, Finland

*Corresponding Author: Lennart Vanglabeke, Department of Cardiac Surgery, University Hospitals Leuven & Department of Cardiovascular Sciences, KU Leuven-University of Leuven, Leuven Belgium.

Received: 30 October 2025; Accepted: 11 November 2025; Published: 05 January 2026

Article Information

Citation:

Lennart Vanglabeke, Tom Verbelen, Jean-Christian Roussel, Christian Lildal Carranza, Lenard Conradi, Koen Cathenis, Giovanni Troise, Julien Guihaire, Juan Bustamante-Munguira, Davide Pacini, Paolo Centofanti, Nicolas Doll, Rafael Llorens, Yanai Ben-Gal, Francesco Musumeci, Tine Philipsen, Laurent de Kerchove, Roberto Lorusso, Alberto Giovanni Tripodi, Alberto Canziani, Antti Valtola, Bart Meuris. The Growing Value of Multicentre, Prospective, Real-world Data: Early-Outcomes of 1000 Patients with the Avalus Aortic Valve. Journal of Surgery and Research. 9 (2026): 01-08.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: As cardiac surgery becomes increasingly complex, real-world data is essential to evaluate bioprosthetic valve performance beyond controlled trials. The Avalus Clinical confidencE (ACE) registry provides real-world insights into the safety and effectiveness of the Avalus valve across diverse patient populations.

Methods: The ACE registry is a prospective, multicentre, single-arm, observational study including 1000 patients undergoing surgical aortic valve replacement with the Avalus bioprosthesis in 26 European centres between 2021-2023. Exclusion criteria were age <18y and salvage surgery, which lead to a real-world study population undergoing aortic valve replacement, either isolated or combined with various other procedures. Primary endpoints included all-cause mortality and disabling stroke. Secondary endpoints assessed prosthetic valve function and major complications. Clinical status and echocardiographic performance were evaluated at discharge and at one-year follow-up.

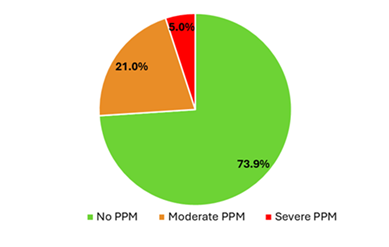

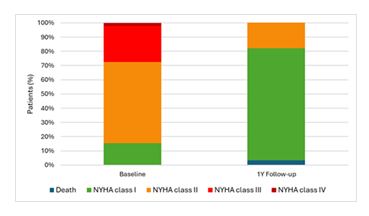

Results: In an all-comers population (mean age: 71.5±6.6years, mean EuroSCORE II: 3.4±5.8), early all-cause mortality was 1.7%. Median implanted valve size was 24mm, with 19.3% of valves being a 19 or 21mm prosthesis. Echocardiographic assessment at discharge showed a mean gradient of 11.6±5.3mmHg, with an effective orifice area of 1.98±0.61cm². Severe patient-prosthesis-mismatch (PPM) was observed in only 5.0% of patients, while 73.9% had no PPM. At one-year followup (n=703), overall mortality remained low at 3.3%, with continued stability in valve performance (mean gradient: 12.2±4.9mmHg). Functional improvement was significant, with 74% of patients improving to NYHA class I or II.

Conclusions: The ACE registry shows low stroke and mortality rates in a complex real-world population, with excellent hemodynamics and minimal PPM at one-year follow-up.

Keywords

<p>Avalus bioprosthetic valve, Surgical aortic valve replacement, Real-world data, Hemodynamic performance, Patient-prosthesis mismatch</p>

Article Details

Introduction

As cardiac surgery evolves, procedures are becoming more complex, with an increasing number of cases requiring the management of multiple conditions simultaneously [1,2]. Additionally, the rise of transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) as an alternative to traditional surgical aortic valve replacement (SAVR) has introduced new challenges and opportunities in the field [3,4]. In this changing landscape, the importance of real-world data is growing. Unlike controlled clinical trials, real-world data reflects the variability seen in everyday practice, capturing outcomes from diverse and often more complex patient populations [5].

In this context, further investigation into the performance of a new bioprosthesis, the Avalus valve (Medtronic Inc., Minneapolis, Minn), is essential. The Pericardial Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement (PERIGON) Pivotal Trial is investigating the safety and efficacy in a selected patient population of isolated AVR with the Avalus bioprosthesis, with or without coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG). To deepen our understanding of such a tissue valve in the real-world setting, the ACE registry was set up [6]. The ACE registry is a prospective, observational, single-arm, multi-centric study, and has reached a significant milestone by enrolling 1000 patients. This registry serves as an important source of real-world data, offering a comprehensive view of the Avalus valve’s performance across various patient profiles and clinical settings. Long-term follow-up is planned, with clinical and echocardiographic evaluations to assess durability over time.

Methods

Patients

Between January 2021 and December 2023, 1000 patients were enrolled in the ACE registry, in 26 centres across 9 countries. The cohort includes patients undergoing AVR using the Avalus valve, encompassing an "all-comers" population. The only exclusion criteria for the registry were patients under the age of 18y and those undergoing salvage surgery [7].

All participants provided written informed consent prior to registry inclusion, including consent for the anonymized processing of their data. The registry received approval from the institutional review board and ethics committee of the University Hospitals Leuven (S63824, 24/3/2020) as leading centre, and from the ethical committees from the other contributing centres. This registry is listed in the clinical trial database with registration number NCT05572710.

Study devices

The Avalus valve is a bioprosthetic heart valve primarily used for SAVR in patients with severe aortic stenosis or regurgitation, made from bovine pericardium tissue, treated with alpha-amino oleic acid as anti-calcification treatment8.

The Avalus valve comes with the typical range of sizes (19 to 29 mm in Europe), accommodating various patient anatomies and allowing for proper fit and function [8].

Study endpoints

Primary end-points: The primary endpoint of the study was defined as the composite of all-cause mortality and disabling stroke.

Secondary endpoints: The secondary endpoints included mortality, stroke, bleeding complications, major vascular complications, pacemaker implantation, prosthetic valve function, PPM, and the need for reintervention.

Mortality was assessed as all-cause mortality, both in-hospital and during follow-up, to determine overall post-procedure survival rates. The incidence of perioperative stroke was tracked, with both ischemic and haemorrhagic events included in this endpoint.

Bleeding complications were categorized according to the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 (VARC-2) classification system, distinguishing between minor, major, and life-threatening events [9]. These included intraoperative bleeding, the need for postoperative blood transfusions, and reoperations due to bleeding. Also, the need for new permanent pacemaker implantation was assessed.

Major vascular complications include thoracic aortic dissection; access site or access-related injuries resulting in death, significant transfusion (≥4units), unplanned intervention, or irreversible organ damage; and distal embolization (non-cerebral) requiring surgery, amputation, or causing irreversible organ damage.

Prosthetic valve performance was evaluated through echocardiographic measurements, including transvalvular gradients and effective orifice area (EOA), while monitoring for paravalvular leaks or structural valve deterioration. The focus here was on assessing hemodynamic performance and valve durability.

An additional endpoint was PPM classification according to VARC-3, which adjusts for obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m²). Severe PPM was defined as indexed EOA ≤0.65 cm²/m² in non-obese and ≤0.55 cm²/m² in obese patients. Moderate PPM was defined as 0.66–0.85 cm²/m² in non-obese and 0.56–0.70 cm²/m² in obese patients. No PPM was defined as indexed EOA >0.85 cm²/m² in non-obese and >0.70 cm²/m² in obese patients [10].

Finally, the need for reintervention was closely monitored. This included cases of prosthetic valve failure, endocarditis, or other complications necessitating repeat valve-related procedures.

Surgical risk factors

We assessed risk factors for cardiovascular surgery using the European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation II (EuroSCORE II) [11]. The EuroSCORE II measures patient risk at the time of cardiovascular surgery and is calculated by a logistic-regression equation. Scores range from 0 to 100%, with higher scores indicating greater risk.

Study oversight

The UZ Leuven group was responsible for the development of the study protocol and the electronic case report forms (eCRFs). They attest to the integrity of the study, ensuring the completeness and accuracy of the data.

Data management

Clinical outcomes and adverse events were evaluated per VARC-2 criteria. Data were collected at discharge and are being collected at one-year follow-up. All data were systematically recorded in a standardized eCRF and securely transferred to a centralized Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) database.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were expressed as numbers and percentages for categorical variables, and as means with standard deviations for continuous variables to convey central tendency and variability. Ranges (x—x) were provided where appropriate to illustrate the spread of the data. Missing variables in patients with available discharge or follow-up echocardiography were addressed using multiple imputation.

Results

Patients

Baseline characteristics are provided in table 1. The mean number of patients per hospital was 38 (1-146). The mean patient age was 71.5±6.6years (42-90), with 12.4% of patients under the age of 65, and 27.2% of patients aged >75y. Female patients comprised 23.5% of the cohort. Over half of the patients presented with at least moderate renal impairment, defined by a creatinine clearance ranging from 50 to 85mL/min, and 84.6% were classified as NYHA class II or higher. The mean EuroSCORE II was 3.4±5.3 (0.52-77.4).

The prevalence of insulin-treated diabetes, prior cardiac surgery, severe mobility impairment, chronic lung disease, endocarditis, critical preoperative state, extracardiac arteriopathy, recent myocardial infarction, and Canadian classification Cardiovascular Society (CCS) class 4 angina was low (Table 1).

Aortic stenosis was present in 84.0% of cases, with a mean aortic valve area of 0.93±0.6cm² and a mean aortic valve gradient of 42.0±20.2mmHg. Pure aortic insufficiency was present in 14.1% of cases. The mean left ventricular ejection fraction was 57.2±10.1%, and 73% of patients had mixed aortic valve disease, with 5.3% having a history of prior cardiac surgery.

|

Characteristic |

Patients (N=1000) |

|

Age (yr) |

71.5±6.6 |

|

Age range |

42—90 |

|

<65y (no.(%)) |

124 (12.4) |

|

>75y (no.(%)) |

272 (27.2) |

|

Female sex (no.(%)) |

233 (23.5) |

|

BMI (kg/m²) |

27.44±4.45 |

|

BSA (m²) |

1.95±0.21 |

|

Renal impairment (no.(%)) |

|

|

Normal |

467/994 (46.9) |

|

Moderate |

432/994 (43.5) |

|

Severe |

95/994 (9.6) |

|

NYHA class (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

I |

152/989 (15.4) |

|

II |

566/989 (57.2) |

|

III |

250/989 (25.3) |

|

IV |

21/989 (2.1) |

|

EuroSCORE II (%) |

3.4±5.3 |

|

Median |

1.88 (IQR 1.14–3.71) |

|

EuroSCORE II range |

0.52—77.4 |

|

Clinical history (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Diabetes: insulin treated |

62/997 (6.2) |

|

Previous cardiac surgery |

52/989 (5.3) |

|

Severe impairment of mobility |

22/982 (2.2) |

|

Chronic lung disease |

68/981 (6.9) |

|

Pulmonary hypertension |

|

|

Moderate |

198/979 (20.2) |

|

Severe |

26/979 (2.7) |

|

Endocarditis |

43/981 (4.4) |

|

Critical preop state |

12/992 (1.2) |

|

Extra-cardiac arteriopathy |

85/993 (8.6) |

|

Recent myocardial infarction |

28/991 (2.8) |

|

Rhythm (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Sinus rhythm |

820/993 (82.6) |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

138/993 (13.9) |

|

Pacemaker |

29/993 (2.9) |

|

CCS class 4 angina |

26/993 (2.6) |

|

Echocardiographic findings |

|

|

Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) |

57.2±10.1 |

|

Aortic valve area (cm²) |

0.93±0.6 |

|

Mean aortic valve gradient (mmHg) |

42.0±20.2 |

|

Peak aortic valve gradient (mmHg) |

63.2±30.6 |

|

Aortic regurgitation (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Mild |

331/988 (33.5) |

|

Moderate |

176/988 (17.8) |

|

Severe |

216/988 (21.8) |

BMI, Body Mass Index; BSA, Body Surface Area; CCS, Canadian classification Cardiovascular Society; EuroSCORE, European System for Cardiac Operative Risk Evaluation; IQR, Interquartile Range; NYHA, New York Heart Association.

Table 1: Baseline characteristics

Procedural characteristics

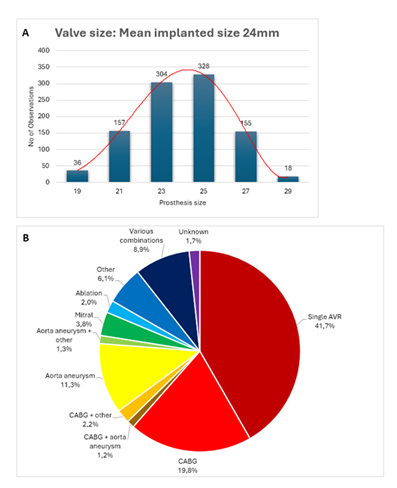

A detailed summary of all procedural characteristics is provided in table 2. Sizes 23 and 25 were the most common and sizes 19 and 29 the least used, as shown in figure 1A. Most procedures were elective, with only 11.0% performed on an urgent or emergent basis. 41.7% of the procedures involved isolated AVR, while the remainder included additional concomitant procedures: CABG (27.1%), mitral valve and/or tricuspid valve repair or replacement (11.8%), ascending aortic aneurysm repair (15.6%), ablation therapy (5.7%). Annulus enlargement was only performed in 0.3% of cases. Figure 1B illustrates the frequency distribution of the various surgical procedures performed.

Figure 1: A) The distribution of prosthesis sizes used in the study cohort, with a mean prosthesis size of 23.9mm and a standard deviation of 2.2mm. B) A pie chart illustrates the distribution of concomitant procedures performed with Avalus valve implantation; combinations occurring in <1% of cases were grouped as ‘various combinations.

For isolated AVR (n=417), median cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was 88.0min (IQR 73.0–105.0) and aortic cross-clamp time was 66.0min (IQR 55.0–80.0). For combined procedures (n=563), median CPB was 126.0min (IQR 104.0–159.0) and an aortic cross-clamp time of 97.0min (IQR 78.0–118.0). A second cross-clamp was required in 18 (1.8%) cases, due to paravalvular leakage, bleeding, or other intraoperative issues. Most procedures were performed via full sternotomy. In single AVR, 29.6% of cases were done using a minimally invasive approach (4.3% anterior thoracotomy, 25.3% mini sternotomy).

|

Characteristic |

Patients (N=1000) |

|

Prosthesis size (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

19 |

36/998 (3.6) |

|

21 |

157/998 (15.7) |

|

23 |

304/998 (30.5) |

|

25 |

328/998 (32.9) |

|

27 |

155/998 (15.5) |

|

29 |

18/998 (1.8) |

|

Urgency (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Elective |

879/997 (88.2) |

|

Urgent |

111/997 (11.0) |

|

Emergent |

7/997 (0.7) |

|

Native valve (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Unicuspid |

1/994 (0.1) |

|

Bicuspid |

256/994 (25.7) |

|

Tricuspid |

710/994 (71.4) |

|

Prosthetic |

27/994 (2.7) |

|

Single AVR (no./total no.(%)) |

417/1000 (41.7) |

|

Concomitant procedures (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

CABG |

271/1000 (27.1) |

|

Number of grafts |

1.77±0.9 |

|

Graft range |

0—5 |

|

Mitral valve repair/replacement |

83/1000 (8.3) |

|

Tricuspid valve repair/replacement |

35/1000 (3.5) |

|

Ascending aorta aneurysm |

156/1000 (15.6) |

|

Ablation treatment |

57/1000 (5.7) |

|

Other |

141/1000 (14.1) |

|

Aortic cross-clamp time (minutes) |

89.0±32.1 |

|

Isolated AVR |

66.0 (IQR 55.0–80.0) |

|

Combined procedures |

97.0 (IQR 78.0–118.0) |

|

Second clamp needed | no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Paravalvular leak |

4/999 (0.4) |

|

Bleeding |

5/999 (0.5) |

|

CPB time (minutes) |

117.2±45.2 |

|

Isolated AVR |

88.0 (IQR 73.0–105.0) |

|

Combined procedures |

126.0 (IQR 104.0–159.0) |

|

Access (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Full sternotomy |

829/996 (83.2) |

|

Mini sternotomy |

137/996 (13.8) |

|

Anterior thoracotomy |

19/996 (1.9) |

|

Use of automatic suturing device (no./total no.(%)) |

4/133 (3.0) |

AVR, Aortic Valve Replacement; CABG, Coronary Artery Bypass Graft; CPB, CardioPulmonary Bypass; IQR, Interquartile Range.

Table 2: Procedural characteristics.

End points at discharge

A complete summary of results at discharge is provided in table 3. At 30 days, the overall mortality was 1,7% (n=17). Stroke occurred in 2.4% of patients, with cerebrovascular accidents accounting for 1.62% and transient ischemic attacks for 0.78%. The majority of these events were ischemic in nature, with a smaller proportion being haemorrhagic. Peri-procedural myocardial infarction was observed in 0.4% of patients. A few patients (n=34) required early reoperation due to bleeding.

Renal function remained stable for most patients: less than 5% experienced stage 2 or 3 acute kidney injury [12]. A small number of patients (n=23) required dialysis. Additionally, 5.7% of patients needed prolonged ventilation, and less than 1% required extracorporeal membrane oxygenation or intra-aortic balloon pump support. The mean ICU and hospital stay was 3.1±5.9 and 10.7±9.6days, respectively.

Echocardiographic assessment showed a stable left ventricular ejection fraction post-procedure, with a significant improvement in effective orifice area (1.98±0.61cm²) and reductions in both mean and peak aortic valve gradients (72.6% and 67.4% decrease, respectively). Paravalvular regurgitation >1/4 was observed in only 0.1% of patients.

Most patients had no PPM (73.9%), while 21.0% had moderate PPM and 5.0% was categorized as severe PPM. After applying multiple imputation to address missing EOA data, the distribution shifted slightly, with 73% of patients showing no PPM, 22% with moderate PPM, and 5% with severe PPM (Figure 2). A significant proportion of patients were prescribed either anticoagulant therapy (28.4%) or antiplatelet therapy (44.8%), while 21.0% received a combination of both treatments.

|

Characteristic |

Patients (N=1000) |

|

Mortality (no./total no.(%)) |

17/1000 (1.7) |

|

Cardiac cause |

7/17 (41.2) |

|

Procedure-related |

1/17 (5.9) |

|

Sudden or unwitnessed death |

2/17 (11.8) |

|

Other |

7/17 (41.2) |

|

Stroke (no./total no.(%)) |

24/989 (2.4) |

|

TIA |

9/24 (37.5) |

|

Ischemic |

4/9 (44.4) |

|

Haemorrhagic |

0/9 (0.0) |

|

Undetermined |

3/9 (33.3) |

|

CVA |

15/24 (62.5) |

|

Ischemic |

10/15 (66.7) |

|

Haemorrhagic |

2/15 (13.3) |

|

Undetermined |

3/15 (20.0) |

|

Periprocedural myocardial infarction (no./total no.(%)) |

4/991 (0.4) |

|

Cardiac reoperation (no./total no.(%)) |

50/992 (5.0) |

|

Bleeding |

34/50 (78.0) |

|

Other |

16/50 (32.0) |

|

Bleeding (no./total no.(%)) |

87/986 (8.8) |

|

Minor bleeding |

32/87 (36.7) |

|

Major bleeding |

44/87 (50.6) |

|

Life-threatening |

14/87 (16.1) |

|

Postoperative pacemaker implantation (no./total no.(%)) |

38/985 (3.9) |

|

Acute kidney injury (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Stage 1 |

69/981 (7.0) |

|

Stage 2 |

23/981 (2.3) |

|

Stage 3 |

23/981 (2.3) |

|

Need for dialysis (no./total no.(%)) |

23/991 (2.3) |

|

Prolonged ventilation (no./total no.(%)) |

56/985 (5.7) |

|

Need for mechanical support (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

ECMO |

4/981 (0.4) |

|

IABP |

5/981 (0.5) |

|

ICU duration (days) |

3.1±5.9 |

|

Hospital duration (days) |

10.7±9.6 |

|

Echocardiographic findings |

|

|

Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) |

55.0±10.0 |

|

Aortic valve area (cm²) |

1.98±0.61 |

|

Mean aortic valve gradient (mmHg) |

11.6±5.3 |

|

Peak aortic valve gradient (mmHg) |

20.7±8.8 |

|

Aortic regurgitation (no./total no.(%)) |

63/952 (6.6) |

|

Intravalvular |

36/952 (3.7) |

|

Mild |

36/36 (100.0) |

|

Paravalvular |

26/952 (2.7) |

|

Mild |

25/26 (96.2) |

|

Moderate |

1/26 (3.8) |

|

PPM |

|

|

No PPM |

327/442 (73.9) |

|

Mild PPM |

93/442 (21.0) |

|

Severe PPM |

22/442 (5.0) |

|

Oral anticoagulants |

362/980 (36.9) |

|

Novel oral anticoagulants |

161/970 (16.6) |

|

Antiplatelet medication |

669/972 (68.8) |

|

Rhythm (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Sinus rhythm |

756/984 (76.8) |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

165/984 (16.8) |

|

Pacemaker |

49/984 (5.0) |

CVA, Cerebrovascular Accident; ECMO, ExtraCorporeal Membrane Oxygenation; IABP, Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump; PPM, Patient-Prosthesis-Mismatch; TIA, Transient Ischemic Attack.

Table 3: Status at discharge.

End points at follow up

A detailed summary of one-year follow-up results is provided in table 4.

During this follow-up period, twenty-three patients died, with four deaths attributed to cardiac causes. Although follow-up data are not yet complete, there was an improvement in NYHA classification, with the average moving from class II to class I and significant reductions in class II and III cases as seen in figure 3.

During follow-up, reoperations were required in 2.8% of patients, with nearly half involving the aortic valve. The reason for these early aortic valve-related re-interventions was endocarditis (n=5).

Echocardiographic assessments indicated a stable left ventricular ejection fraction. A slight decrease in the EOA was observed compared to discharge values (1.98±0.61cm²); however, the average EOA at follow-up (1.82±0.50cm²) remained well-preserved among the 703 patients who completed 1-year follow-up. Mean and peak aortic valve gradients have remained stable. The proportion of patients on anticoagulant and antiplatelet therapy decreased over the year.

|

Characteristic |

Patients (N=703) |

|

Mortality (no./total no.(%)) |

23/703 (3.3) |

|

Cardiac cause |

4/23 (17.4) |

|

Rhythm (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

Sinus rhythm |

540/654 (82.6) |

|

Atrial fibrillation |

76/654 (11.6) |

|

Pacemaker |

26/654 (4.0) |

|

NYHA class (no./total no.(%)) |

|

|

I |

513/650 (78.9) |

|

II |

120/650 (18.5) |

|

III |

13/650 (2.0) |

|

IV |

2/650 (0.03) |

|

Cardiac reoperation (no./total no.(%)) |

19/680 (2.8) |

|

Aortic valve |

7/680 (1.0) |

|

Non aortic valve |

12/680 (1.8) |

|

Endocarditis (no./total no.(%)) |

19/677 (2.8) |

|

Stroke (no./total no.(%)) |

11/677 (1.6) |

|

TIA |

3/11 (27.3) |

|

Ischemic |

0/3 (0.0) |

|

Haemorrhagic |

0/3 (0.0) |

|

Undetermined |

3/3 (100.0) |

|

CVA |

8/11 (72.7) |

|

Ischemic |

6/8 (75.0) |

|

Haemorrhagic |

1/8 (12.5) |

|

Undetermined |

1/8 (12.5) |

|

Pacemaker implantation (no./total no.(%)) |

20/674 (2.9) |

|

Rehospitalization for valve related symptoms (no./total no.(%)) |

23/674 (3.4) |

|

Echocardiographic findings |

|

|

Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) |

58.6±8.7 |

|

Aortic valve area (cm²) |

1.82±0.5 |

|

Mean aortic valve gradient (mmHg) |

12.2±4.9 |

|

Peak aortic valve gradient (mmHg) |

20.6±8.4 |

|

Aortic regurgitation (no./total no.(%)) |

38/606 (6.3) |

|

Intravalvular |

25/38 (65.8) |

|

Mild |

25/25 (100) |

|

Paravalvular |

13/38 (34.2) |

|

Mild |

13/13 (100) |

|

PPM |

|

|

No PPM |

172/265 (64.9) |

|

Mild PPM |

75/265 (28.3) |

|

Severe PPM |

18/265 (6.8) |

|

Oral anticoagulants |

108/669 (16.1) |

|

Novel oral anticoagulants |

181/670 (27.0) |

|

Antiplatelet medication |

382/667 (57.2) |

CVA, Cerebrovascular Accident; NYHA, New York Heart Association; PPM, Patient-Prosthesis-Mismatch; TIA, Transient Ischemic Attack.

Table 4: Status at 1 year follow-up.

Discussion

Summary of evidence

This multicentre, real-world, all-comers ACE registry is following 1000 patients submitted to AVR with a recent biological prosthesis in various clinical settings and highlights the immediate performance of the Avalus aortic valve in both routine and complex procedures. We observed low early mortality (1.7% at discharge; 3.3% at one year), representing a 50% reduction compared with median EuroSCORE II–predicted risk (3.4%). Valve-related adverse events, including stroke (1.6%) and reintervention (2.8%), were infrequent, underscoring the valve’s safety in routine and higher-risk contexts.

The Avalus valve displayed excellent hemodynamic performance, as evidenced by significant improvements in the EOA and low aortic transvalvular gradients. At discharge, the mean EOA increased to 1.98±0.61cm², doubling from baseline, with mean and peak aortic valve gradients decreasing significantly. At one year follow-up, these values remained stable with minimal changes in gradients, demonstrating stable short-term function. These findings validate the valve's ability to sustain effective blood flow, even over extended periods. In actual measured diameters, the Avalus exhibits the largest inner diameters among several commercially available aortic valve prostheses [13]. We see this reflected in exceptionally low incidences of PPM at discharge, 73.9% of patients exhibited no PPM, 21.0% moderate PPM, and only 5.0% severe PPM, rising modestly to 6.8% at one year, partly reflecting attrition of larger EOA valves during follow-up. Compared to literature, such rates of PPM are favourable: rates of moderate PPM are reported as high as 55-64%, and severe PPM up to 34% [14,15]. In the initial analysis of the PERIGON Pivotal Trial, the PPM rate was found to be very high, only 24.5% of patients were reported to have no PPM, compared to 73.9% in our analysis. However, a recent re-analysis of the PERIGON trial data by a different core lab identified 79.5% of patients with no PPM, aligning closely with our findings and corresponding well with observations from real-world studies [16,17]. We report here also a low PPM rate. Low PPM rates can beneficially influence early and late outcome [18,19].

One-year follow-up data from 703 patients revealed stable valve function and safety outcomes. Notably, anticoagulant and antiplatelet usage decreased at one year compared to discharge, reflecting improved patient status and reduced reliance on pharmacotherapy. Moreover, the ACE registry underscores the power of real-world data to complement randomized trials, capturing performance in high-risk or complex cases often excluded from RCTs.

These real-world findings are consistent with the results of the PERIGON pivotal trial, which reported 82.6% overall survival at seven years in 1132 Avalus recipients [20]. Interestingly, in PERIGON, mean transvalvular gradients were 13.1mmHg across the whole patient cohort at discharge. In our series, mean gradients seem to be lower at 11.6mmHg. Potentially, the increasing use and familiarity with the sizing procedure beneficially influenced valve sizing and hemodynamic outcome. Compared to PERIGON, our series really reflects real-world, all-comers use of the prosthesis.

The ACE registry underlines the role of real-world data in assessing the performance of a surgical valve. Unlike formal controlled trials, real-world data reflect diverse, complex patient populations. The registry confirms the valve's safety and hemodynamic performance, emphasizing how real-world evidence can complement controlled trials to prove the early effectiveness of bioprosthetic valves. Longer-term follow-up is planned to assess durability.

Limitations

While the study offers valuable insights, it has its limitations. The collected data is site-reported and relies on the accuracy and consistency of participating centres, without external validation by an independent core laboratory, introducing the potential for reporting bias. Furthermore, 70% of enrolled patients had completed one-year follow-up at the time of manuscript writing, restricting the conclusions drawn from the results. The lack of a comparator group hinders head-to-head comparisons of the Avalus valve’s performance against other bioprosthetic valves or surgical approaches. These limitations highlight the need for ongoing follow-up to confirm these findings and assess their comparative effectiveness.

Conclusions

The ACE registry’s early results reinforce the Avalus bioprosthesis as a safe and effective surgical valve in real world practice. With low mortality, stroke, and PPM rates, and stable hemodynamics at one year, the Avalus valve offers a reliable option for SAVR, particularly in patients seeking alternatives to lifelong anticoagulation or presenting with complex cardiac pathology. These findings, together with seven year durability demonstrated in PERIGON, underscore the Avalus valve’s role in contemporary AVR and warrant our initiated further long-term follow up to confirm durability.

Acknowledgements

Our department has support from a grant by Medtronic.

References

- Pierri MD, Capestro F, Zingaro C, et al. The changing face of cardiac surgery patients: an insight into a Mediterranean region. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 38 (2010): 407-413.

- Pettersson GB, Martino D, Blackstone EH, et al. Advising complex patients who require complex heart operations. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 145 (2013): 1159-1169.

- Sigala E, Kelesi M, Terentes-Printzios D, et al. Surgical Aortic Valve Replacement in Patients Aged 50 to 70 Years: Mechanical or Bioprosthetic Valve 90% A Systematic Review. Healthc 11 (2023): 1771.

- Yokoyama Y, Kuno T, Toyoda N, et al. Ross Procedure Versus Mechanical Versus Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve Replacement: A Network Meta-Analysis. J Am Heart Assoc 12 (2023): e8066.

- Franklin JM, Schneeweiss S. When and How Can Real World Data Analyses Substitute for Randomized Controlled Trials? Clin Pharmacol Ther 102 (2017): 924-933.

- Klautz RJM, Kappetein AP, Lange R, et al. Safety, effectiveness and haemodynamic performance of a new stented aortic valve bioprosthesis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 52 (2017): 425-431.

- Murray CR, Balsam LB. Commentary: Outliers-Salvage operations and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons risk model. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 159 (2020): 203-204.

- Avalus™ Bioprosthesis for Heart Valve Replacement. Medtronic (2024).

- Kappetein AP, Head SJ, Genereux P, et al. Updated standardized endpoint definitions for transcatheter aortic valve implantation: the Valve Academic Research Consortium-2 consensus document. Eur Heart J 33 (2012): 2403-2418.

- Dismorr M, Glaser N, Franco-Cereceda A, et al. Effect of Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch on Long-Term Clinical Outcomes After Bioprosthetic Aortic Valve Replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol 81 (2023): 964-975.

- Nashef SA, Roques F, Sharples LD, et al. EuroSCORE II. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 41 (2012): 734-745.

- AKI Definition. Kidney International Supplements 2 (2012): 19-36.

- Van Boxtel AGM, Mariani MA, Ebels T. All surgical supra-annular aortic valvar tissue prostheses are labelled too large. Interdiscip CardioVasc Thorac Surg 36 (2023): 12.

- Ternacle J, Théron A, Bernard A. Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch after Aortic Valve Replacement: Valve Size Matters? J Heart Valve Soc 1 (2024): 15.

- Clavel MA, Webb JG, Pibarot P, et al. Comparison of the Hemodynamic Performance of Percutaneous and Surgical Bioprostheses for the Treatment of Severe Aortic Stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 53 (2009): 1883-1891.

- Klautz RJM, Rao V, Reardon MJ, et al. Examining the typical hemodynamic performance of nearly 3000 modern surgical aortic bioprostheses. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 65 (2024).

- Bavaria JE, Desai ND, Cheung A, et al. The St Jude Medical Trifecta aortic pericardial valve: Results from a global, multicenter, prospective clinical study. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 147 (2014): 590-597.

- Moon MR, Pasque MK, Munfakh NA, et al. Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch After Aortic Valve Replacement: Impact of Age and Body Size on Late Survival. Ann Thorac Surg 81 (2006): 481-489.

- Blais C, Dumesnil JG, Baillot R, et al. Impact of Valve Prosthesis-Patient Mismatch on Short-Term Mortality After Aortic Valve Replacement. Circ 108 (2003): 983-988.

- Sabik JF, Rao V, Dagenais F, et al. Seven-year outcomes after surgical aortic valve replacement with a stented bovine pericardial bioprosthesis in over 1100 patients: a prospective multicentre analysis. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 67 (2024).

Impact Factor: * 4.2

Impact Factor: * 4.2 Acceptance Rate: 72.62%

Acceptance Rate: 72.62%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks