Congenital Common Bile Duct Agenesis: An Extremely Rare Anomaly - Two Case Reports and Review of Literature

Louis F Chai1, Alexander E Trebelev2, Gary S Xiao3*

1Department of Surgery, Rutgers Robert Wood Johnson Medical School, Robert Wood Johnson Place, New Brunswick, NJ 08901

2Quantum Imaging & Therapeutic Associates, 629 D Lowther Road Lewisberry, PA 17339

3Transplant and Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery, Tower Health Transplant Institute, Reading Hospital. 301 South Seventh Avenue, Suite 320, West Reading, PA 19611

*Corresponding author: Gary Xiao, MD, FACS. Transplant and Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery, Tower Health Transplant Institute, Reading Hospital, 301 South Seventh Avenue, Suite 320, West Reading, PA 19611, USA

Received: 09 July 2021; Accepted: 16 July 2021; Published: 06 February 2026

Article Information

Citation: Louis F Chai, Alexander E Trebelev, Gary S Xiao. Congenital Common Bile Duct Agenesis: An Extremely Rare Anomaly - Two Case Reports and Review of Literature. Journal of Surgery and Research. 9 (2026): 47-53.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Variations of the hepatico-pancreatic-biliary system are frequently vascular, but biliary duct deviations can occur.1 In the extra-hepatic biliary system, anomalies occur during foregut development and include accessory ducts, anomalous insertions, or agenesis. Though anomalies may be clinically silent, discovery usually occurs in symptomatic patients resulting in imaging or intraoperatively during exploration. The rarest of anomalies is common bile duct agenesis, resulting in formation of a cholecystohepatic duct, gallbladder interposition, or perhaps most appropriately, a hepaticocystic duct.2-3 We present here two cases discovered intraoperatively and an updated review on this anomaly.

Keywords

Hepaticocystic duct, Common bile duct agenesis, Extrahepatic biliary tree, Cholecystectomy

Article Details

1. Introduction

Biliary tree abnormalities and variations on the anatomy have been described in many forums, with studies showing incidences as low as 0.58% and as high as 47.2% of patients studied [1-4]. These variations are of particular importance during surgical interventions as ligation or excision of improperly identified structures around the area can cause significant morbidity and mortality when undiagnosed. These anomalies can occur anywhere along the biliary tree, but the least commonly seen is the agenesis of the common bile duct, resulting in the formation of a hepaticocystic duct. In this variation, the hepatic ducts, either individually or conjoined, directly enter in various locations of the gallbladder and the cystic duct directly flows into the duodenum [5]. This poses particular concern during cholecystectomies should the interposition be unnoticed, resulting in persistent proximal leakage of bile from the channels.

Case 1

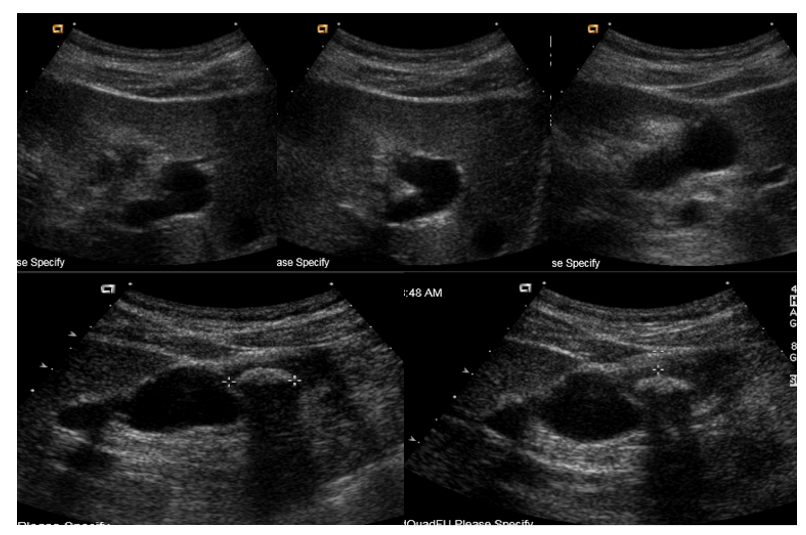

The patient is a 32-year-old Asian male who presented as an outpatient for evaluation of repeated epigastric and RUQ abdominal discomfort. The patient had no significant past medical or surgical history. Original imaging from several years prior showed a small stone in the gallbladder and he had been having intermittent abdominal pain for 2 years. Work-up of the symptoms at presentation included a RUQ ultrasound that revealed a 1.9cm calcified stone in the fundus of the gallbladder, causing localized wall thickening, and a 3mm channel that was believed to be the common bile duct. The remainder of the exam was insignificant for any other pathology in the visualized hepato-pancreatico-biliary system (Figure 1). The patient was scheduled for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy given the significant increase in size of the gallstone and with the diagnosis of symptomatic cholelithiasis. The patient initially underwent the conventional 4-port cholecystectomy without any complication. After careful dissection in the area of the gallbladder neck, Calot’s Triangle was exposed, the critical view of safety was obtained, and what was thought to be the cystic duct was identified. Clips were placed proximal to the gallbladder neck and further distal along the cystic duct. The cystic artery was similarly clipped and both isolated structures were divided between the clips. The gallbladder was then dissected off of the liver bed without any complication until transection of the tissues around the scarred and fibrosed fundus to completely remove the gallbladder revealed a bile leak from a 4 to 5mm duct-like structure in this area. Given the leak, a clip was temporarily placed on the structure and the gall bladder was removed to allow for further examination of the anatomy and to perform an intraoperative laparoscopic cholangiogram. The clips were removed from the remnant cystic duct stump and the cholangiogram catheter was placed into the cystic duct. When contrast was injected into the duct, it went directly into the duodenum. The cholangiogram was then repeated after withdrawing the catheter to be certain that the tip was not too deep within the common bile duct. The results were the same and no proximal reflux was seen into a common bile duct even after morphine was given to contract the sphincter of Oddi. At this time, with unclear anatomy, the procedure was converted from a laparoscopic to open case in order to properly explore the porta hepatis via a right subcostal Kocher incision. The portal vein and hepatic artery were identified with no visualized common bile duct. A biliary probe was used on the proximal and distal stumps from the transected ductal structures with the proximal stump reaching the left and right intrahepatic ducts and the distal duct tracing directly into the duodenum. A biliary catheter was then inserted into the proximal duct to perform an intra-operative cholangiogram, which showed a duct stump 5 millimeters below the bifurcation of the right and left intra-hepatic ducts and a normal intra-hepatic biliary tree. This indicated that the most likely anatomy was a hepaticocystic duct secondary to agenesis of the common bile duct. The distance between the proximal and distal stump measured approximately 3cm. A retrocolic, Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy was performed to repair the transected proximal hepatic duct. The patient remained stable throughout the entirety of the case and was managed on the surgical floor post-operatively. The patient recovered well, was able to tolerate a regular diet, and was discharged to home with normal liver function. On subsequent outpatient follow-up, the patient was fully recovered from the surgery and returned to his daily activities. He continues to be well four years post-operatively.

Case 2

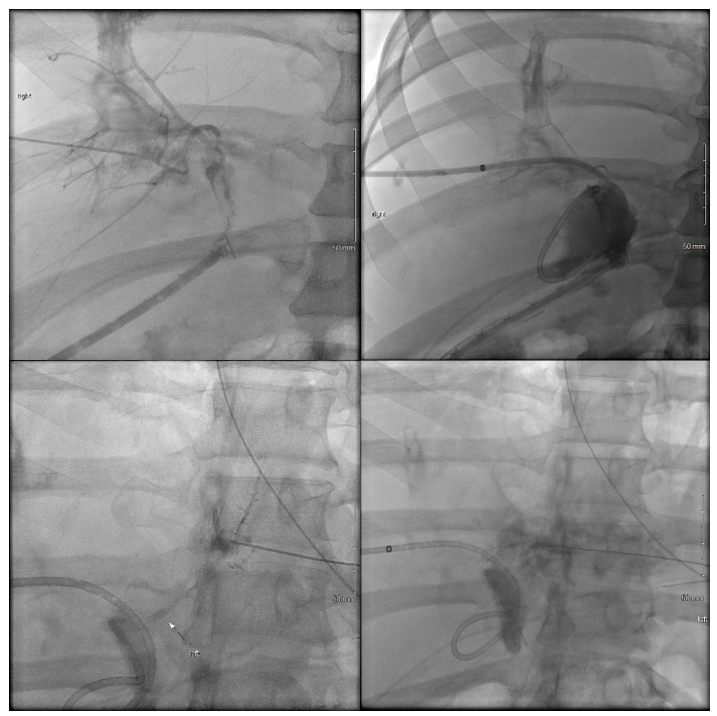

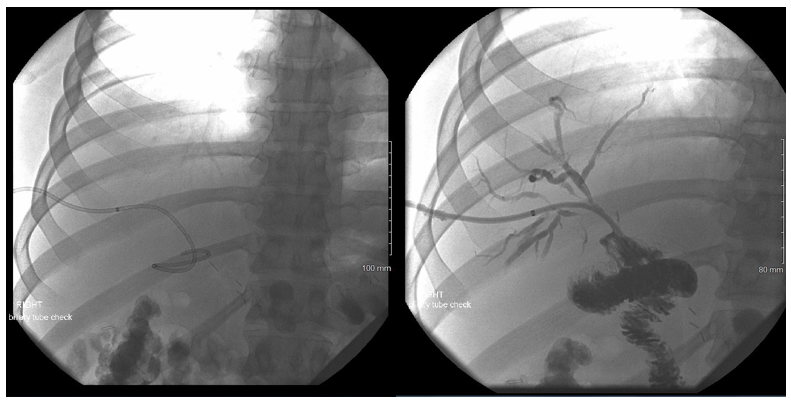

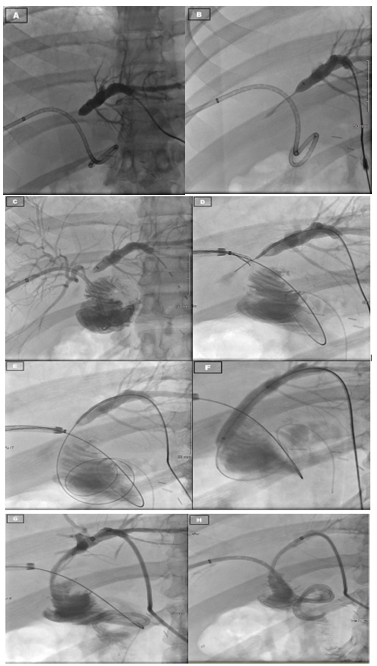

A 29-year-old male presented to an outside hospital for evaluation for abdominal pain and was diagnosed with acute cholecystitis. The patient was taken to the operating room nine days prior to presentation at our hospital for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Though the dissection was difficult, the case proceeded uneventfully and the patient was subsequently discharged post-operatively. The patient returned to the outside hospital on post-operative day 7 with high fevers and had a collection seen on ultrasonography, which was then identified as a bile duct leak on HIDA scan. An ERCP was performed at this time, but the biliary duct could not be cannulated due to an obstruction. The patient was brought back to the operating at this point for an exploratory laparotomy. After exploration, the surgeons identified a bile leak, but could not identify the proximal bile duct. Intra-operative cholangiogram was performed through the distal duct, which revealed flow into the duodenum, but the proximal duct could not be identified. Given the complexity of the anatomy and the case, the patient was transferred to us for further surgical management. On arrival, the intraoperative cholangiogram from the outside hospital was reviewed and a diagnosis of congenital agenesis of the common bile duct as suspected as flow through the ligated cystic duct went directly into the duodenum. At this time, Interventional Radiology (IR) was consulted to perform at PTC to review the biliary anatomy and create a road map for further repair. However, only the right hepatic system could be catheterized as the left hepatic duct was too small (Figure 2a). The cholangiogram through the right PTC showed a large bile leak, but no extra-hepatic ducts could be identified at all. Given these findings, the patient was then taken to the operating room for exploratory laparotomy. Upon examining the surgical site, the distal bile duct was significantly dilated to 9-10 millimeters in diameter. Proximally, the right PTC catheter placed by IR was emerging from the intra-hepatic right biliary system and further exploration did not reveal any intra-hepatic biliary ducts from the left or any extra-hepatic ducts. A complete portahepatis lymphadenectomy and dissection with skeletonized hepatic artery and portal vein was performed in an attempt to localize the left intra-hepatic duct and right extra-hepatic duct to no avail. It was suspected that the patient had variant anatomy with common bile duct agenesis with the left hepatic duct connecting to the right hepatic duct high in the liver parenchyma. Given this, continuity was restored to the biliary tree via a hepaticoportal enterotomy, or Kasai procedure. The tissue around the porta hepatis and the right PTC wrapped around an enterotomy in a two layer anastomosis. The patient was managed for the first three post-operative days in the intensive care unit before being transferred to the surgical floors where his recovery continued before ultimately being discharged. Subsequent follow-up appointments revealed adequate patency of the right-sided biliary catheters and ultimately, dilation of the left sided biliary system to permit cannulation and drainage into the intact hepaticoportal enterostomy (Figure 2b and 2c). Clinically, the patient remains stable and with unremarkable laboratory results 18 months from surgery.

Figure 2a: Initial cholangiography on presentation on 5/14/2017 for Case 2. From top left clockwise: cholangiography showing intact right hepatic duct system with distal extravasation of contrast at ligated common hepatic duct, insertion of percutaneous trans-hepatic catheter with flow into the jejunal limb, collapsed and inaccessible distal left hepatic duct system, and collapsed and inaccessible proximal left hepatic duct system.

Figure 2c: Follow up cholangiography several months after surgery for Case 2. Pictures as labeled: A - Dilated left hepatic duct system, B - catheter passing through severely stenotic region of left hepatic duct, unable to float into common hepatic duct, C - right hepatic duct cholangiogram with flow into jejunal limb, D - Removal of right PTC catheter over wire, insertion of left hepatic duct wire, snare of left hepatic duct wire through right hepatic duct, E - left hepatic duct wire dragged through common hepatic duct into duodenum via right hepatic duct snare, F - balloon dilation of stenotic area of left hepatic duct, G - insertion of PTC catheter into left hepatic duct, H - reinsertion of right PTC catheter.

2. Discussion

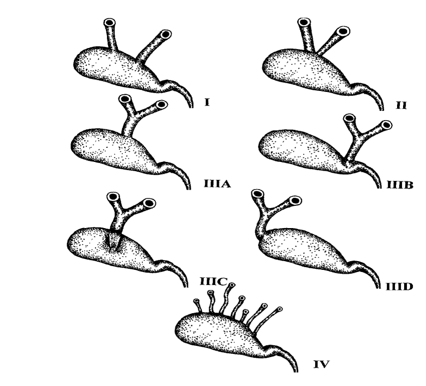

The biliary tree has embryological roots as the most caudal portion of the foregut and arises from what is known as the hepatic diverticulum. This divides into two parts, the liver and gallbladder, with the cells in between developing into the cystic and bile ducts to form the fully developed biliary tree that enters the duodenum [6]. The variations in anatomy arise during this stage of development and can arise in any of the involved structures. In terms of the hepaticocystic duct, it is believed that the aberrancy occurs secondary to delayed separation of the hepatic and cystic tissues, persistence of fetal communications, or failure of the cells of the common bile duct to proliferate or recannalize [1,5]. Thus, the gallbladder and cystic duct are interpositioned between the hepatic ducts and the duodenum as the only common channel for biliary outflow. With regards to biliary tree aberrancies, the hepaticocystic duct appears to be the rarest of all anomalies, which can include duplicated structures, anomalous insertions, and congenital agenesis. In a review of the literature, there have only been 25 reports of varying detail of this developmental abnormality in the world as far as we are aware (Table 1) [7-24]. Of these cases, multiple variants have been described with different insertions of the hepatic ducts into the gallbladder with the common link between all of them being the agenesis of the CBD and the solitary outflow of the entire biliary track being provided by the cystic duct into the duodenum [25-31]. This classification system was first described by Losanoff et al. and consists of four types (Figure 3). In Type I, each hepatic duct inserts into the gallbladder separately. Type II results in the joining of the hepatic ducts when they enter the gallbladder. Type III has multiple variants based on where the insertion of the common hepatic duct enters the gallbladder. Type IIIa inserts in the superior portion of the gallbladder wall, IIIb into the neck of the gallbladder, IIIc into the posterior wall of the gallbladder, and IIId into the gallbladder fundus. The type IV variant has multiple individual ducts draining the liver inserting into the wall of the gallbladder [3]. In our first patient, we observed the Type IIId variant of the hepaticocystic duct whereas the second did not appear to match any of Losanoff’s classifications. Presentation of extra-hepatic biliary tree abnormalities can be hard to diagnose and distinguish pre-operatively from normal anatomy. Often, pathology presents with symptoms of RUQ pain, jaundice, nausea, vomiting or fevers with laboratory findings of leukocytosis or elevated liver enzymes, all of which may be due to cholelithiasis, choledocholithiasis, cholangitis, or hepatic pathology [3,5,15,16,20-24]. Work-up may include RUQ ultrasounds, computed tomography (CT), magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or radioactive nucleotide studies such as the HIDA scan. Of these, abnormalities would most likely be discovered on HIDA as flow of the nucleotide is observed through the biliary tree, though CT or MRI may also reveal anatomic variations. However, workup is usually limited to RUQ ultrasound in the correct clinical setting for gallbladder disease before operative management may be indicated, which is what occurred in our two cases [17,19]. Thus, diagnoses of biliary tree aberrancies are generally not obtained until operative exploration or intraoperative cholangiogram for unclear anatomy [3,20,25]. Our first patient’s anatomy was initially noted when there was persistent bile leak noted from a duct near the fundus of the gallbladder and subsequent porta hepatis exploration and intraoperative cholangiogram. Imaging highlighting the proximal left and right hepatic duct and the transected cystic duct leading to the duodenum from Case 2 is shown in Figure 2a-2c. Consequences of an unrecognized biliary duct abnormality could be catastrophic, leading to significant morbidity and mortality. With anomalous hepatic ducts inserting at various locations on the gallbladder, ligation is essentially guaranteed while performing a cholecystectomy, especially if the surgeon is unaware of their presence [26]. While small caliber ducts may be ligated without any complications, accessory ducts with large lumens can cause significant leakage of bile, infection, or poor nutrient absorption. Severe consequences include formation of sub-phrenic abscesses, cirrhosis, external biliary fistulas, frank peritonitis, and even death [4,6,21,27]. When hepaticocystic ducts are diagnosed, various management strategies can be employed depending on when duct anatomy is discovered. When identified prior to removal of the gallbladder, a planned partial cholecystectomy could be performed with a choledochoplasty to preserve the biliary outflow into the duodenum through to remnant cystic duct [15,19-20,22]. If the cholecystectomy has already been completed, leaving behind a one or more proximal hepatic duct stumps and the distal cystic duct stump, primary anastomosis can be performed or a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy can be used to achieve adequate elimination of bile [5,15,19,21]. Primary anastomosis should only be attempted if is not a significant defect resulting from the cholecystectomy, if there will be anastamotic tension, or if there will not be high risk of biliary stricture [16,19,21]. The distance between our hepatic stump and cystic duct stump after cholecystectomy in Case 1 was approximately 3cm and had too large of a defect to perform a primary anastomosis. No discernible left hepatic duct could be found radiographically or on surgical exploration in Case 2. Thus, we opted for a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy to re-establish continuity to the biliary tree in Case 1 and a hepaticoporto enterostomy in Case 2 given the anatomical remnants post-cholecystectomy in each of the patients. The patients did not experience any complications from the surgeries and both remain well post-operatively.

|

Case Report |

Symptoms |

Variant |

Diagnosis |

Management |

|

Abeysuriya et. al. |

N/A |

IIIb |

Autopsy |

N/A |

|

Aristotle et. al. |

N/A |

IIIb |

Autopsy |

N/A |

|

Chiavola et. al. |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Crucknell HH. |

Unknown |

IIIa |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Elhamel A. |

RUQ pain, jaundice |

I |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Partial cholecystectomy, choledochoplasty |

|

Harada et al. |

Epigastric pain |

IIIb |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Partial cholecystectomy, choledochoplasty |

|

Hashmonai et al. |

Asymptomatic |

IIId |

Open exploration, post-operative cholangiogram |

Partial cholecystectomy, choledochoplasty |

|

Jackson et al. |

Epigastric pain, jaundice |

I |

Open exploration, post-operative cholangiogram |

Partial cholecystectomy, choledochoplasty |

|

Kaushik et al. |

Symptomatic cholelithiasis |

I or IIIb? (separate entrance into neck) |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Partial cholecystectomy |

|

Krishna et al. |

Epigastric pain |

IIIb |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

|

Losanoff et al. |

RUQ pain |

IIId |

Open exploration |

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

|

Markle GB |

RUQ pain, nausea, vomiting |

III? |

Open exploration |

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

|

Mittal et al. |

Abdominal pain |

IIIa or IIIc |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

|

Moosman et al. |

Unknown |

I |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Nikolov et al. |

Unknown |

I |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Nygren et al. |

Unknown |

IIIb |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Olsha et al. |

Unknown |

IIIa |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Rabinovitch et al. |

Abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, fevers |

I (variation - R. duct only into GB), separate into duodenum |

Open exploration |

Partial cholecystectomy, choledochoplasty |

|

Redkar et al. |

RUQ pain, jaundice |

IIIb |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy |

|

Schorlemmer et al. |

Jaundice |

IV |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Cholecystoduodenostomy |

|

Shah et al. |

Cholangitis |

IIIb |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Partial cholecystectomy, choledochoplasty |

|

Stokes et al. |

RUQ pain, jaundice |

IIIc |

Open exploration, intraoperative cholangiogram |

Biliary tree reconstruction via Y-tube |

|

Walia et al. |

Unknown |

I |

Unknown |

Unknown |

|

Williams et al. |

RUQ abdominal pain, jaundice |

I |

Open exploration |

Primary anastomosis and dilation |

|

Zimmerman et al. |

Unknown |

IIIa |

Unknown |

Primary anastomosis |

Table 1: Known reported cases of common bile duct agenesis and hepaticocystic ducts [1,2,5,7-24, 28-31].

3. Conclusion

Aberrancies of the biliary tree are uncommon findings, with a wide variety of incidences quoted by different reviews and case series. However, with cholecystectomies being one of the most common surgical procedures performed, these abnormalities have operative significance and correct identification is essential in preventing complications that are potentially fatal. Though conventional work-up with RUQ ultrasound may not identify such anatomical variations, proper exploration and identification of the critical view of safety intra-operatively during a cholecystectomy may prevent these complications. If there is doubt about the anatomy during the procedure, a cholangiogram should be performed to better delineate structures. This would allow for early identification before the gallbladder resection, potentially sparing the patient from a larger operation to create a Roux-en-Y hepaticojejunostomy for biliary continuity and could instead be managed with primary anastomosis or choledochoplasty after partial cholecystectomy. Though rare, when abberant anatomy is discovered, a hepaticocystic duct should be considered as an anatomical variation for proper diagnosis and management in biliary tree pathology perioperatively.

References

- Abeysuriya V, Salgado S, Deen KI, et. al. Hepaticocystic duct and a rare extra-hepatic “cruciate” arterial anastomosis: a case report. J Med Case Rep 2 (2008): 37.

- Aristotle S, Felicia C, Sakthivelavan S. An Unusual Variation of Extra Hepatic Biliary Ductal System: Hepaticocystic Duct. J Clin Diagn Res 5 (2011): 984-986.

- Losanoff JE, Jones JW, Richman BW, et al. Hepaticocystic duct: a rare anomaly of the extrahepatic biliary system. Clin Anat15 (2002): 314-315.

- Lamah M and Dickson GH. Congenital anatomical abnormalities of the extrahepatic biliary duct: a personal audit. Surg Radiol Anat 21 (1999): 325-327.

- Losanoff JE, Kjossev KT, Katrov E. Hepaticocystic duct - A case report. Surg Radiol Anat. 18 (1996): 339-341.

- Lamah M, Karanjia ND, Dickson GH. Anatomical variations of the extrahepatic biliary Tree: Review of the world literature. Clin Anat 14 (2001): 167-172.

- Walia HS, Abraham TK, Baraka A. Gall-bladder interposition: a rare anomaly of the extrahepatic ducts. Int Surg 71 (1986): 117-121.

- Olsha O, Steiner A, Rivkin LA et al. Congenital absence of the anatomic common bile duct. Case Report. Acta Chir Scand 153 (1987): 387-390.

- Nikolov K, Chobanov G, Belchev B, et al. A rare case of gallbladder interposition in the extrahepatic bile ducts. Khirurglia (Sofiia) 47 (1994): 52-53.

- Schorlemmer GR, Wild RE, Mandell V. Cholecystohepatic connections in a case of extrahepatic biliary Atresia. JAMA 252 (1984): 1319-1320.

- Moosman DA. The surgical significance of six anomalies of the biliary duct system. Surg Gynecol Obstet 131 (1970): 655-660.

- Zimmermann HG. Intercalate gallbladder in the ductus hepaticus-choledochus, a rare anomaly of bile duct. Chirurg 48 (1977): 73-76.

- Nygren EJ, Barnes WA. Atresia of the common hepatic duct with shunt via an accessory duct. Report of a case. AMA Arch Surg 68 (1954): 337-343.

- Chiavola E, Grio V, Pagani V. A rare congenital malformation of the bile ducts: presence of hepato-cholecystic ducts with agenesis of the common bile duct. Minerva Chir 43 (1988): 177-181.

- Harada N, Sugawara Y, Ishizawa T, et al. Resection of hepaticocystic duct which is a rare anomaly of the extrahepatic biliary system: a case report. J Med Case Rep 7 (2013): 279.

- Jackson JB and Kelly TR. Cholecystohepatic Ducts: Case Report. Ann Surg 159 (1964): 581-584.

- Kaushik R and Attri A. Hepaticocystic Duct: A Case Report. Internet J Surg 6 (2004): 1-5.

- Krishna RP and Behari A. Interposition of Gallbladder - a rare extrahepatic biliary anomaly. Indian J Surg 73 (2011): 453-454.

- Mittal T, Pulle MV, Dey A, et al. Congenital absence of the common bile duct: A rare anomaly of extrahepatic biliary tract. J Min Access Surg 12 (2016): 281-282.

- Rabinovitch J, Rabinovitch P, and Zisk HJ. Rare anomalies of the extrahepatic bile ducts. Ann Surg 144 (1956): 93-98.

- Redkar RG, Davenport M, Myers N, et. al. Association of oesophageal atresia and cholecystohepatic duct. Pediatr Surg Int 15 (1999): 21-23.

- Shah O. The missing common bile duct (hepaticocystic duct). Surgery 142 (2007): 424-425.

- Stokes TL and Old Jr. L. Cholecystohepatic duct. Am J Surg 135 (1978): 703-705.

- Williams C and Williams AM. Abnormalities of the Bile Ducts. Ann Surg 141 (1955): 598-605.

- Foster JH and Wayson EE. Surgical significance of aberrant bile ducts. Am J Surg 104 (1962): 14-19.

- Goor DA and Ebert PA. Anomalies of the biliary tree. Report of a repair of an accessory bile duct and review of the literature. Arch Surgery 104 (1972): 302-309.

- Neuhof H and Bloomfield S. The surgical significant of an anomalous cholecystohepatic duct. Ann Surg 122 (1945): 260-265.

- Hashmonai M and Kopelman D. An anomaly of the extrahepatic biliary system. Arch Surg 130 (1995): 673-675.

- Markle GB. Agenesis of the common bile duct. Arch Surg 116 (1982): 350-352.

- Elhamel A. A Rare Extrahepatic Biliary Anomaly. HPB Surgery 1 (1989): 353-358.

- Crucknell HH. Malformation of the gallbladder and hepatic ducts. Tran Path Soc Lond 22 (1871): 163-164.

Impact Factor: * 4.2

Impact Factor: * 4.2 Acceptance Rate: 72.62%

Acceptance Rate: 72.62%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks