Multiligament Knee Injuries in Adolescents: Distinct Patterns Based on Energy Mechanisms and Polytrauma Status

Allan K Metz1, Collin DR Hunter1, Joseph Featherall1, Natalya McNamara1, Cody T McGrale1, Pat Greis1, Travis G Maak1, Stephen K Aoki1, Antonio Klasan2,3, Justin J Ernat1*

1Department of Orthopaedics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84108, USA

2AUVA UKH Steiermark, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Graz, Austria

3Johannes Kepler University Linz, Austria

*Corresponding Author: Justin J Ernat, Department of Orthopaedics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, Utah 84108, USA

Received: 07 September 2025; Accepted: 16 September 2025; Published: 09 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Allan K Metz, Collin DR Hunter, Joseph Featherall, Natalya McNamara, Cody T McGrale, Pat Greis, Travis G Maak, Stephen K Aoki, Antonio Klasan, Justin J Ernat. Multiligament Knee Injuries in Adolescents: Distinct Patterns Based on Energy Mechanisms and Polytrauma Status. Journal of Surgery and Research. 8 (2025): 534-541.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Purpose: Characterize differences in ligamentous injury patterns in adolescents with MLKIs by different mechanisms and polytrauma status, with the hypothesis that high-energy (HE) and polytrauma (PT) patients would have more severe injuries.

Materials and Methods: Demographics, clinical characteristics, radiographic findings, and intraoperative variables were obtained on surgical MLKIs in the adolescent population from a single tertiary-care institution between June 2008 through October 2022. HE versus lowenergy (LE) and PT versus non-polytrauma (NPT) mechanisms were stratified. Subgroup comparisons were made based on body mass index, age, sex, number/type of ligaments injured, and surgeries performed. Statistical analysis included t-test and Chi-square analyses.

Results: A total of 38 adolescent MLKI patients were included (mean age 16.0 ± 1.6 years, body mass index 24.6 ± 4.3 points, 65.8% male). There was an increased rate of posterior cruciate ligament (PCL; 77.8% vs 24.1%; P = 0.004), lateral collateral ligament (LCL; 77.8% vs 34.5%; P = 0.022), and medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL) (44.4% vs 10.3%; P = 0.021) injuries in HE vs. LE, respectively. PT compared to NPT cases also had higher rates of LCL (83.3% vs 37.5%; P = 0.038) and MPFL (50.0% vs 12.5%; P = 0.030) injuries. Mean number of ligaments injured (excluding MPFL) were increased in HE vs. LE (3.2 ± 0.7 vs 2.2 ± 0.7; P < 0.001) and PT vs. NPT (3.2 ± 0.8 vs 2.3 ± 0.8; P = 0.014) cases, respectively.

Conclusion: MLKIs resulting from HE mechanisms were associated with increased rates of PCL, LCL, and MPFL injuries, with PT patients having increased rates of LCL and MPFL injuries. HE and PT patients experienced a greater number of injured ligaments than LE and NPT patients. LCL injuries were associated with increased rates of injury in both groups and should be scrutinized in these patients during workup.

Level of Evidence: Level IV: Retrospective Case Series

Keywords

<p>Multiligament knee injury, MLKI, Adolescent, Sports medicine, Knee arthroscopy, Sports medicine</p>

Article Details

Introduction

Multiligament knee injuries (MLKIs) are rare but severe injuries to the knee joint that can present with diverse injury patterns resulting from various mechanisms. These mechanisms include high-energy (HE), low-energy (LE), and very-low energy mechanisms, but may also encompass polytrauma (PT) to non-polytrauma (NPT) settings and have an estimated prevalence of near 0.02% [1]. These injuries involve partial or complete disruption of at least two of the primary knee ligaments: the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), posterior cruciate ligament (PCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and lateral collateral ligament (LCL), and often lead to significant functional impairment and long-term sequelae such as early-onset arthritis, chronic pain, knee instability, neurovascular injury, and need for additional revision surgery [2-6]. The incidence of MLKIs is increasing in all settings regardless of mechanism and trauma-status, further highlighting the importance of increasing our understanding of these injuries [7-10].

MLKIs have been extensively documented in adults, whereas ligamentous injury patterns have been characterized in relation to mechanism severity, and patient reported outcomes have been documented over short- and long-term follow-up [11-15]. However, comparatively few studies have investigated MLKIs in adolescents, who may present with different biomechanical profiles and unique challenges, thereby necessitating distinct treatment considerations [15,16]. A single study of 20 adolescent patients by Godin et al. suggested generally favorable outcomes following treatment of these injuries [16]. Despite the severity of these injuries, existing data on ligamentous patterns in this population remain sparse and poorly understood, underscoring the need for further investigation to guide effective treatments.

The aim of this study is to describe the specific ligamentous injury patterns seen in adolescents with MLKIs, focusing on the mechanism of injury. By characterizing these patterns, we hope to improve understanding of MLKIs in this patient population, which can guide both surgical decision-making and treatment algorithms. Our hypothesis is that HE injury mechanisms and PT patients would have an overall increased number of ligaments injured in their MLKIs.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective review included adolescent patients who underwent surgical management for MLKIs at a tertiary care academic institution between April 2008 and October 2023. Patients were eligible if they 1) had at least two surgically treated ligamentous injuries involving the ACL, MCL, PCL, and/or LCL, 2) had a documented mechanisms of injury, 3) had available magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies, 4) had operative reports accessible, and 4) were of adolescent age (10-19 years) at the time of surgery as defined by the World Health Organization [17]. Exclusion criteria included 1) revision procedures for prior MLKI surgery, 2) cases managed nonoperatively or with arthroplasty, and 3) chronic injuries exceeding 1 year from the time of injury to surgical intervention. Operative and MRI reports were reviewed to confirm eligibility. MCL and LCL injuries were classified using a three-tier grading system: Grade 1 for mild sprains, Grade 2 for partial tears, and Grade 3 for complete tears with associated instability [18,19]. Ligament injury patterns were determined based on MRI and surgical findings and were classified based on anatomic description as well as total number of ligaments injured (ACL, PCL, MCL and LCL). We further subclassified ligament-injury patterns into ACL-based, PCL-based, and bicruciate-based patterns. Number of ligaments treated surgically was also recorded. Lastly, a note was made as to whether there was documented injury to the medial patellofemoral ligament (MPFL).

Patient demographic information (age, sex, body mass index (BMI)) was extracted from the electronic medical record (EMR; Epic Systems Corporation, Verona, WI). Additionally, vascular and peroneal nerve injuries were documented through clinical evaluation and physical exam findings collected from the EMR. All clinical and imaging data were entered into a secure REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture, Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN) database for longitudinal data management.

Injury mechanisms were categorized by their severity and associated systemic trauma into polytrauma (PT) versus non-polytrauma (NPT), and high-energy (HE) versus low-energy (LE) groups. PT MLKIs were defined by concomitant injuries to the head, spine, extremities, abdomen, or pelvis, whereas NPT MLKIs were limited to isolated knee injuries. HE MLKI mechanisms involved high-impact trauma such as motor vehicle collisions or falls from significant heights (>1.5 meters), while LE mechanisms encompassed less severe mechanisms such as sports-related injuries and ground-level falls [20].

Statistical Analysis

The compiled data were analyzed using SPSS version 27 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Comparative analyses were conducted between PT and NPT as well as HE and LE mechanisms for variables including age, sex, BMI, number of ligaments injured, specific ligament injury patterns, and treatment modalities (repair, reconstruction, or nonsurgical). Shapiro-Wilk testing was performed to assess data distribution normality. Continuous variables were compared using independent t-tests, while categorical variables were analyzed with chi-square tests. A significance threshold of p<0.05 was applied for all statistical comparisons.

Results

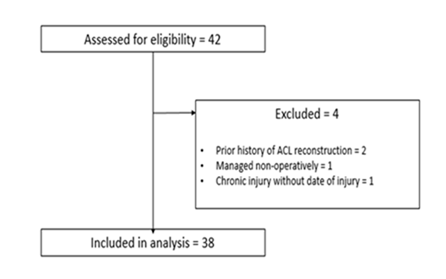

A total of 42 consecutive adolescent patients with multiligament knee injuries (MLKIs) were reviewed with 38 patients included in the study (Figure 1). The mean age was 16.0 years (SD = 1.6; range 12-19 years), with a mean BMI of 24.6 (SD = 4.3). Most of the patients were male (65.8%, 25/38) (Table 1). For high-energy (HE) versus low-energy (LE) MLKIs, there were 9 patients (24%) in the HE group and 29 patients (76%) in the LE group. The mean age was 16.5 years (SD = 1.4, range 15-19 years) in the HE group and 15.8 years (SD = 1.6; range 15-19 years) in the LE group (P = 0.305). The mean BMI was comparable between groups: 24.0 (SD = 3.5) for HE and 24.6 (SD = 4.6) for LE (P = 0.717). Males constituted 44.4% (4/9) of the HE group and 72.4% (21/29) of the LE group (P = 0.122). Mechanism of injury showed significant differences between groups (P < 0.001): MVCs were the predominant mechanism in the HE group, accounting for 33.3% (3/9), but none in the LE group. Sports injuries accounted for 86.2% (25/29) of LE cases, compared to 22.2% (2/9) in the HE group. Injuries classified as “other” mechanisms occurred in 44.5% (4/9) of HE cases and 13.8% (4/29) of LE cases (Table 2). For polytraumatic (PT) versus non-polytraumatic (NPT) MLKIs, 6 patients (16%) were classified as PT, while 32 patients (84%) were classified as NPT. The mean age in the PT group was 16.3 years (SD = 1.7; range 15-19 years), compared to 15.9 years (SD = 1.6; range 13-19 years) in the NPT group (P = 0.631). The mean BMI was 25.5 (SD = 2.9) for the PT group and 24.3 (SD = 4.6) for the NPT group (P = 0.531). Males comprised 50.0% (3/6) of the PT group and 68.8% (22/32) of the NPT group (P = 0.374). Mechanisms of injury differed significantly between our PT versus NPT groups (P < 0.001): MVCs accounted for 50.0% (3/6) of PT cases and 0% of NPT cases. Sports injuries were more frequent in the NPT group, accounting for 81.3% (26/32), compared to 16.7% (1/6) in the PT group. Injuries classified as “other” mechanisms represented 33.3% (2/6) of PT cases and 18.7% (6/32) of NPT cases (Table 3).

Flow diagram outlining the inclusion and exclusion criteria for study enrollment. Of 42 patients assessed, 4 were excluded due to prior ACL reconstruction (n=2), non-operative management (n=1), or chronic injury without a documented injury date (n=1). A total of 38 adolescent patients were included in the final analysis.

|

Total Patients |

38 |

|

|

Age, years |

16.0 ± 1.6 |

|

|

BMI |

24.6 ± 4.3 |

|

|

Sex, Male |

25 (65.8%) |

|

|

ACL Injury |

35 (92.1%) |

|

|

ACL Surgery |

34 (89.5%) |

|

|

PCL Injury |

14 (36.8%) |

|

|

PCL Surgery |

9 (23.7%) |

|

|

MCL Injury |

26 (68.4%) |

|

|

Grade 1 |

6 (15.8%) |

|

|

Grade 2 |

6 (15.8%) |

|

|

Grade 3 |

14 (36.8%) |

|

|

MCL Surgery |

22 (100.0%) |

|

|

LCL Injury |

17 (44.7%) |

|

|

Grade 1 |

2 (5.2%) |

|

|

Grade 2 |

2 (5.2%) |

|

|

Grade 3 |

13 (34.2%) |

|

|

LCL Surgery |

14 (36.8%) |

|

|

MPFL Injury |

7 (18.4%) |

|

|

MPFL Surgery |

2 (5.2%) |

|

|

MPFL Allograft |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

MPFL Repair |

2 (5.2%) |

|

|

Bicruciate injuries (ACL/PCL) |

5 (13%) |

|

|

ACL-based injuries |

29 (76%) |

|

|

PCL-based injuries |

4 (11%) |

|

|

Mean # ligaments injured excluding MPFL (STD) |

2.3 ± 0.8 |

|

|

Impaction Fracture |

10 (26%) |

|

|

Popliteal Artery Injury |

1 (3%) |

|

|

Peroneal Nerve Palsy |

8 (21%) |

*P-value calculated by chi-squared analysis

**Percent undergoing surgery calculated based on available number of injuries in each group

Demographic and injury characteristics of adolescent patients with multiligament knee injuries (MLKI) are summarized. Surgical percentages are calculated based on the number of patients with confirmed injuries to that ligament. Radiographic grading was performed for MCL and LCL injuries. Bicruciate injuries refer to concomitant ACL and PCL injuries. Mean number of ligaments injured excludes MPFL injuries.

Table 1: Demographics, injury, radiographic grading, and surgeries in adolescent MLKI patients.

|

Variables |

High Energy |

Low Energy |

p-value |

|

Total Patients |

9 |

29 |

|

|

Age, years |

16.5 ± 1.4 |

15.8 ± 1.6 |

0.305 |

|

BMI |

24.0 ± 3.5 |

24.6 ± 4.6 |

0.717 |

|

Sex |

|||

|

Male |

4 (44.4%) |

21 (72.4%) |

0.122 |

|

Mechanism: |

<0.001 |

||

|

MVC |

3 (33.3%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

Sports Injury |

2 (22.2%) |

25 (86.2%) |

|

|

Other |

4 (44.5%) |

4 (13.8%) |

*Age and BMI variables reported as mean (SD) or n (%).

** Students T- test used for continuous variable comparisons, Chi-squared analysis used for categorical comparisons

Table 2: Demographics of Adolescent High-Energy and Low-Energy MLKIs cohorts.

Injury and Surgical Intervention Frequencies and Patterns

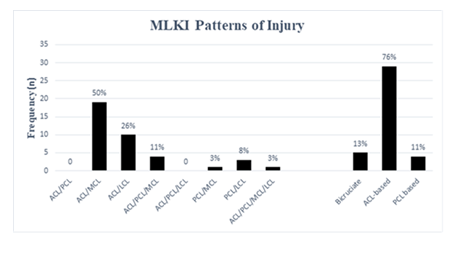

The most common ligamentous pattern involved in this cohort was ACL/MCL with 19 (50%), followed by ACL/LCL with 10 (26%), ACL/PCL/MCL with 4 (11%), PCL/LCL with 3 (8%), and both PCL/MCL and ACL/PCL/MCL/LCL had 1 (3%) each (Figure 2). There were no ACL/PCL or ACL/PCL/LCL injuries observed. ACL-based were the most common MLKIs accounting for 76% (29/38) followed by bicruciate with 13% (5/38) and PCL-based with 11% (4/38) (Figure 2). ACL injuries were observed in 92.1% (35/38) of cases, with surgical intervention performed in 89.5% (34/38). PCL injuries occurred in 36.8% (14/38) of patients, with 23.7% (9/38) undergoing surgical repair or reconstruction. MCL injuries were identified in 68.4% (26/38) of patients, distributed as follows: Grade 1 (15.8%, 6/38), Grade 2 (15.8%, 6/38), and Grade 3 (36.8%, 14/38). Surgical intervention for MCL injuries was performed in 100% (22/22) of cases. LCL injuries were present in 44.7% (17/38) of patients, categorized as Grade 1 (5.2%, 2/38), Grade 2 (5.2%, 2/38), and Grade 3 (34.2%, 13/38). LCL surgery was conducted in 36.8% (14/38) of cases. MPFL injuries occurred in 18.4% (7/38) of patients, with surgical repair performed in 5.2% (2/38), including no cases of MPFL allograft usage and 5.2% (2/38) undergoing MPFL repair (Table 3).

|

Variables |

Polytraumatic |

Non-Polytraumatic |

p-value |

|

Total Patients |

6 |

32 |

|

|

Age, years |

16.3 ± 1.7 |

15.9 ± 1.6 |

0.631 |

|

BMI |

25.5 ± 2.9 |

24.3 ± 4.6 |

0.531 |

|

Sex |

|||

|

Male |

3 (50.0%) |

22 (68.8%) |

0.374 |

|

Mechanism: |

<0.001 |

||

|

MVC |

3 (50.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

|

|

Sports injury |

1 (16.7%) |

26 (81.3%) |

|

|

Other |

2 (33.3%) |

6 (18.7%) |

Demographics and injury mechanisms are compared between polytraumatic and non-polytraumatic MLKI cohorts. Age and BMI are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical comparisons were made using Student’s t-test for continuous variables and chi-squared analysis for categorical variables.

Table 3: Demographics of Adolescent Polytraumatic and Non-polytraumatic MLKIs cohorts.

In HE versus LE MLKIs, ACL injuries were observed in 100.0% (9/9) of HE cases compared to 89.7% (26/29) of LE cases (P = 0.315). PCL injuries were significantly more common in HE cases (77.8%, 7/9) compared to LE cases (24.1%, 7/29) (P = 0.004). LCL injuries occurred more frequently in the HE cases (77.8%, 7/9) compared to LE cases (34.5%, 10/29) (P = 0.022). ACL-based MLKIs occurred at higher rates in LE mechanisms (83%, 24/29) compared to HE (56%, 5/9), while bicruciate MKLIs were more frequent in HE mechanisms (33%, 3/9) compared to those of LE (7%, 2/29) and PCL-based MLKIs were observed at similar rates across both HE (11%, 1/9) and LE (10%, 3/29) mechanisms, although these findings were not statistically significant (P = 0.115) (Table 5). Similarly, MPFL injuries were significantly more common in HE cases (44.4%, 4/9) compared to LE cases (10.3%, 3/29) (P = 0.021). The mean number of ligaments injured was significantly higher in HE cases (3.2 ± 0.7) compared to LE cases (2.2 ± 0.7) (P < 0.001) (Table 4).

|

Variables |

High Energy |

Low Energy |

p-value |

|

Total Patients |

9 |

29 |

|

|

ACL Injury |

9 (100%) |

26 (89.7%) |

0.315 |

|

ACL Surgery |

8 (88.9%) |

26 (100%) |

0.948 |

|

PCL Injury |

7 (77.8%) |

7 (24.1%) |

0.004 |

|

PCL Surgery |

4 (57.1%) |

5 (71.4%) |

0.094 |

|

MCL Injury |

6 (66.7%) |

20 (69.0%) |

0.897 |

|

Grade 1 |

2 (22.2%) |

4 (13.8%) |

0.544 |

|

Grade 2 |

1 (11.1%) |

5 (17.2%) |

0.650 |

|

Grade 3 |

3 (33.3%) |

11 (37.9%) |

0.803 |

|

MCL Surgery |

6 (100.0%) |

20 (100.0%) |

0.897 |

|

LCL Injury |

7 (77.8%) |

10 (34.5%) |

0.022 |

|

Grade 1 |

1 (11.1%) |

1 (3.4%) |

0.368 |

|

Grade 2 |

1 (11.1%) |

1 (3.4%) |

0.368 |

|

Grade 3 |

5 (55.6%) |

8 (27.6) |

0.122 |

|

LCL Surgery |

6 (85.7%) |

8 (80.0%) |

0.034 |

|

MPFL Injury |

4 (44.4%) |

3 (10.3%) |

0.021 |

|

MPFL Surgery |

1 (25.0%) |

1 (33.3%) |

0.529 |

|

MPFL Allograft |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

|

MPFL Repair |

1 (100.0%) |

1 (100.0%) |

- |

|

Bicruciate injuries (ACL/PCL) |

3 (33%) |

2 (7%) |

|

|

ACL-based injuries |

5 (56%) |

24 (83%) |

|

|

PCL-based injuries |

1 (11%) |

3 (10%) |

|

|

Mean # ligaments injured (STD) |

3.2 ± 0.7 |

2.2 ± 0.7 |

<0.001 |

|

Impaction Fracture |

4 (44.4%) |

5 (17.2%) |

0.094 |

Comparison of ligament injury patterns, severity grades, and surgical rates between high-energy and low-energy MLKI cohorts. P-values were calculated using chi-squared analysis unless otherwise indicated. Fisher’s Exact Test was used for bicruciate, ACL-based, and PCL-based injury comparisons due to small sample sizes. High-energy injuries were associated with significantly higher rates of PCL, LCL, and MPFL injuries, as well as a greater mean number of ligaments injured.

Table 4: Ligamentous mechanism, injury and radiographic grading, and surgeries: Adolescent High-Energy and Low-Energy MLKIs cohorts

In PT versus NPT MLKIs, ACL injuries were observed in 100.0% (6/6) of PT cases and 90.6% (29/32) of NPT cases (P = 0.435). PCL injuries were present in 66.7% (4/6) of PT cases compared to 31.3% (10/32) in NPT cases (P = 0.099), with surgical repair performed in 50.0% (2/4) of PT cases and 70.0% (7/10) of NPT cases (P = 0.545). LCL injuries were significantly more common in PT cases (83.3%, 5/6) compared to NPT cases (37.5%, 12/32) (P = 0.038). ACL-based MLKIs occurred at higher rates in NPT mechanisms (78%, 25/32) compared to PT (67%, 4/6), while bicruciate MKLIs were more frequent in PT mechanisms (33%, 2/6) compared to those of NPT (9%, 3/32) and PCL-based MLKIs were observed at similar rates across both HE (11%, 1/9) and LE (10%, 3/29) mechanisms, although these findings were not statistically significant (P = 0.367) (Table 5).MPFL injuries were present in 50.0% (3/6) of PT cases compared to 12.5% (4/32) of NPT cases (P = 0.030). The mean number of ligaments injured was significantly higher in PT cases (3.2 ± 0.8) compared to NPT cases (2.3 ± 0.8) (P = 0.014) (Table 5).

|

Polytrauma |

Non-polytrauma |

p-value |

|

|

Total Patients |

6 |

32 |

|

|

ACL Injury |

6 (100.0%) |

29 (90.6%) |

0.435 |

|

ACL Surgery |

6 (100.0%) |

28 (96.6%) |

0.360 |

|

PCL Injury |

4 (66.7%) |

10 (31.3%) |

0.099 |

|

PCL Surgery |

2 (50.0%) |

7 (70.0%) |

0.545 |

|

MCL Injury |

4 (66.7%) |

22 (68.8%) |

0.920 |

|

Grade 1 |

1 (16.7%) |

5 (15.6%) |

0.949 |

|

Grade 2 |

1 (16.7%) |

5 (15.6%) |

0.949 |

|

Grade 3 |

2 (33.3%) |

12 (37.5%) |

0.846 |

|

MCL Surgery |

3 (75.0%) |

22 (100.0%) |

0.374 |

|

LCL Injury |

5 (83.3%) |

12 (37.5%) |

0.038 |

|

Grade 1 |

1 (16.7%) |

1 (3.1%) |

0.173 |

|

Grade 2 |

1 (16.7%) |

1 (3.1%) |

0.173 |

|

Grade 3 |

3 (50%) |

10 (31.3%) |

0.374 |

|

LCL Surgery |

4 (80.0%) |

10 (83.3%) |

0.099 |

|

MPFL Injury |

3 (50.0%) |

4 (12.5%) |

0.030 |

|

MPFL Surgery |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (50.0%) |

0.529 |

|

MPFL Allograft |

0 (0.0%) |

0 (0.0%) |

- |

|

MPFL Repair |

0 (0.0%) |

2 (50.0%) |

- |

|

Bicruciate injuries (ACL/PCL) |

2 (33%) |

3 (9%) |

|

|

ACL-based injuries |

4 (67%) |

25 (78%) |

|

|

PCL-based injuries |

0 |

4 (13%) |

|

|

Mean # ligaments injured (STD) |

3.2 ± 0.8 |

2.3 ± 0.8 |

0.014 |

|

Impaction Fracture |

4 (66.7%) |

6 (18.8%) |

0.014 |

Ligament injury patterns, grading, and surgical rates are compared between polytraumatic and non-polytraumatic MLKI cohorts. Statistical analysis was performed using chi-squared tests, with Fisher’s Exact Test applied for comparisons involving bicruciate, ACL-based, and PCL-based injuries. Polytraumatic injuries were associated with significantly more MPFL injuries, a higher number of ligaments injured, and increased incidence of impaction fractures.

Table 5: Ligamentous mechanism, injury and radiographic grading, and surgeries: Adolescent Polytraumatic and Non-polytraumatic MLKIs cohorts.

Discussion

The findings of this study highlight several significant differences in injury patterns between HE and LE MLKIs, as well as between PT and NPT MLKIs in adolescent patients. Rates of LCL injuries were notably higher in both the HE and PT groups when compared to their respective LE and NPT counterparts. Similarly, PCL injuries were more frequently observed in the HE group compared to the LE group. The mean number of ligaments injured, including the ACL, PCL, MCL, and LCL, was significantly greater in both the HE and PT groups, emphasizing the increased severity and complexity of these injuries. Thus, our hypothesis was confirmed.

Our findings suggest that adolescent MLKIs, especially those involving HE or PT mechanisms, may exhibit unique injury characteristics compared to those in adults, with 50.0% of our patients sustaining an ACL and MCL injury, 26.3% sustaining an ACL and LCL injury, and 36.8% sustaining any kind of LCL injury with a mean number of ligaments injured of 2.3 ±0.8. A review by LaPrade et al of 194 adult patients with MLKI from sporting injuries had a mean age of 34.5 years demonstrated that the most common ligament combination was ACL and LCL at 39.2%, ACL and MCL at 25.8%, and 56.7% sustaining some combination of LCL injury [21]. A review by Nagaraj et al of 60 adult patients with a mean age of 31.2 years in majority HE injury mechanisms (MVC) demonstrated that 30.0% presented with an ACL and PCL injury, 36.7% presented with an ACL and MCL injury, and 11.7% presented with an ACL, MCL, and PCL injury, with LCL injuries in any combination being seen in only 10.1% and an overall mean number of ligaments injured of 2.2 [22]. These two studies demonstrate varying patterns of ligament injury in MLKIs with differences from our own, highlighting the heterogeneity across mechanism and age of patient sustaining a MLKI. The present study’s observed higher rates of LCL and PCL injuries in HE and PT mechanisms found in our study is a similar finding to those found in the adult population [13], further highlighting the importance of recognizing the severity and complexity of these cases. Impaction fractures were also more common in the PT group, suggesting that the presence of polytrauma may exacerbate bone-related injuries in addition to ligamentous damage.

The current state of literature regarding MLKIs in adolescent patients has focused on reported outcomes following surgery. A study by Sankar et al. investigating outcomes of twelve adolescent patients with ACL/MCL pattern MLKIs from sports injuries demonstrated 100% return to preinjury level of sport [23]. Godin et al. demonstrated improved outcomes of twenty adolescent patients between the ages of 14-19 years undergoing single-stage MLKI reconstructions with a total of five (25%) of their patients experiencing ACL/MCL tears but did not report mechanism of injury in these cases [16]. A case review of three patients by Badrinath et al. demonstrated good short-term outcomes, although had none of these patients had MCL involvement [24]. The relatively high rates of successful return to sport seen in previous adolescent studies, such as those by Sankar et al. and Godin et al., are encouraging. However, these studies largely represent MLKIs of lower complexity compared to the more severe injury patterns seen in our HE and PT cohorts. Future research should aim to further elucidate the long-term outcomes of these more complex cases, particularly in terms of functional recovery and quality of life.

This investigation is subject to several inherent limitations. First, this study is retrospective which poses various restraints pertaining to data availability and potential biases inherent in historical data collection. Second, although the sample size of this study is larger than others pertaining to adolescent MLKIs, it is not as large as the adult cohort studies. Another limitation pertains to the study population, which was exclusively sourced from a single hospital network. Although this could limit the generalizability of the findings, it is worth noting that the data were collected through the collaboration of four experienced orthopaedic sports surgeons within a tertiary academic center (a level 1 trauma facility) that receives referrals for MLKIs from over five neighboring states. This approach ensures a broad representation that likely reflects wider patient demographics and injury profiles. However, the retrospective nature and multiple surgeons does introduce a treatment bias pertaining to the timing, staging, graft selection, and repair/reconstruction/nonoperative treatment decisions that were made. Despite these limitations, we believe that the findings of this study add meaningful insights to the body of research on MLKI injuries. The study did not evaluate outcomes, which are an important aspect for the prognosis in this young cohort [2].

Conclusion

In conclusion, MLKIs resulting from HE mechanisms or occurring in PT patients were associated with increased rates of PCL, LCL, and MPFL injuries compared to those caused by LE mechanisms or in NPT patients. As anticipated, HE and PT patients experienced a greater number of injured ligaments than LE and NPT patients. Furthermore, LCL injuries were more common in both HE and PT groups, emphasizing the need for heightened vigilance in managing these injuries. These findings highlight the importance of understanding injury mechanisms and trauma severity in the clinical decision-making process for adolescent MLKIs, thereby informing tailored surgical and rehabilitation strategies for this population.

Availability of data and materials

The de-identified datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available in order to protect patient privacy, but they are available from the corresponding author,JE, upon reasonable request and with institutional approval.

References

- Rihn JA, Groff YJ, Harner CD, et al. The acutely dislocated knee: evaluation and management. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 12 (2004): 334-346.

- Klasan A, Maerz A, Putnis SE, et al. Outcomes after multiligament knee injury worsen over time: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc.

- Murray IR, Makaram NS, Geeslin AG, et al. Multiligament knee injury (MLKI): an expert consensus statement on nomenclature, diagnosis, treatment and rehabilitation. Br J Sports Med 58 (2024): 1385-1400.

- Ng JWG, Myint Y, Ali FM. Management of multiligament knee injuries. EFORT Open Rev 5 (2020): 145-155.

- Smith MP, Klott J, Hunter Pt, et al. Multiligamentous Knee Injuries: Acute Management, Associated Injuries, and Anticipated Return to Activity. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 30 (2022): 1108-1115.

- Vicenti G, Solarino G, Carrozzo M, et al. Major concern in the multiligament-injured knee treatment: A systematic review. Injury 50 (2019): S89-S94.

- Arom GA, Yeranosian MG, Petrigliano FA, et al. The changing demographics of knee dislocation: a retrospective database review. Clin Orthop Relat Res 472 (2014): 2609-2614.

- Kennedy JC. Complete Dislocation of the Knee Joint. J Bone Joint Surg Am 45 (1963): 889-904.

- Levy BA, Dajani KA, Whelan DB, et al. Decision making in the multiligament-injured knee: an evidence-based systematic review. Arthroscopy 25 (2009): 430-438.

- Louw QA, Manilall J, Grimmer KA. Epidemiology of knee injuries among adolescents: a systematic review. Br J Sports Med 42 (2008): 2-10.

- Dean RS, DePhillipo NN, Kahat DH, et al. Low-Energy Multiligament Knee Injuries Are Associated With Higher Postoperative Activity Scores Compared With High-Energy Multiligament Knee Injuries: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of the Literature. Am J Sports Med 49 (2021): 2248-2254.

- Everhart JS, Du A, Chalasani R, et al. Return to Work or Sport After Multiligament Knee Injury: A Systematic Review of 21 Studies and 524 Patients. Arthroscopy 34 (2018): 1708-1716.

- Hunter CDR, Featherall J, McNamara N, et al. High-energy and polytraumatic multiligament knee injuries more commonly involve the LCL and PCL versus low-energy or isolated injuries. Orthopaedic Journal of Sports Medicine (2025).

- Webster EK, Feller AJ. Exploring the High Reinjury Rate in Younger Patients Undergoing Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction. The American Journal of Sports Medicine 44 (2016): 2827-2832.

- Wiggins AJ, Grandhi RK, Schneider DK, et al. Risk of Secondary Injury in Younger Athletes After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Am J Sports Med 44 (2016): 1861-1876.

- Godin JA, Cinque ME, Pogorzelski J, et al. Multiligament Knee Injuries in Older Adolescents: A 2-Year Minimum Follow-up Study. Orthop J Sports Med 5 (2017): 2325967117727717.

- Sacks D. Age limits and adolescents. Paediatr Child Health 8 (2003): 577-578.

- Wijdicks CA, Griffith CJ, Johansen S, et al. Injuries to the medial collateral ligament and associated medial structures of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 92 (2010): 1266-1280.

- Yaras RJ, O'Neill N, Mabrouk A, et al. Lateral Collateral Ligament Knee Injury. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL) 2024.

- Moatshe G, Chahla J, LaPrade RF, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of multiligament knee injury: state of the art. Journal of ISAKOS 2 (2017): 152-161.

- LaPrade RF, Chahla J, DePhillipo NN, et al. Single-Stage Multiple-Ligament Knee Reconstructions for Sports-Related Injuries: Outcomes in 194 Patients. Am J Sports Med 47 (2019): 2563-2571.

- Nagaraj R, Shivanna S. Pattern of multiligament knee injuries and their outcomes in a single stage reconstruction: Experience at a tertiary orthopedic care centre. J Clin Orthop Trauma 15 (2021): 156-160.

- Sankar WN, Wells L, Sennett BJ, et al. Combined anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament injuries in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop 26 (2006): 733-736.

- Badrinath R, Carter CW. "Multiligamentous" Injuries of the Skeletally Immature Knee: A Case Series and Literature Review. J Am Acad Orthop Surg Glob Res Rev 2 (2018): e079.

Impact Factor: * 4.2

Impact Factor: * 4.2 Acceptance Rate: 72.62%

Acceptance Rate: 72.62%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks