Stoma Intubation, Isolation and Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Complex Stoma-Associated Wounds: New Technique and Case Series

Nick Browning1, Michael Okocha1,2,3*, Matthew Doe1,3, and Ann Lyons1

1Department of General Surgery, Southmead Hospital, Bristol, UK

2Institute of Continuing Education, University of Cambridge, UK

3Department of General Surgery, Royal United Hospital, Bath, UK.

*Corresponding Author: Michael Okocha, General Surgery Offices, Southmead Hospital, North Bristol NHS Trust, Southmead Way, BS10 5NB, United Kingdom.

Received: 28 December 2025; Accepted: 05 January 2025; Published: 06 February 2026

Article Information

Citation: Nick Browning, Michael Okocha, Matthew Doe, Ann Lyons. Stoma Intubation, Isolation and Negative Pressure Wound Therapy for Complex Stoma-Associated Wounds: New Technique and Case Series. 9 (2026): 34-39.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: The use of negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) in colorectal surgery has been demonstrated for treating perineal defects, enterocutaneous fistula and stoma dehiscence. Here we describe a technique for closure of complex stoma-associated wounds using a novel commercial intubation device alongside NPWT to protect the surrounding wound from the stoma effluent. Clinically the patients were managed by an MDT approach including specialist nurse practitioners, dieticians, colorectal nurses, stoma nurses and critical care. The device has previously described for use with enterocutaneous fistula. We present two cases that have been successfully treated with this technique.

Technique and Cases: The first case is of an 88 year-old women with a retracted loop ileostomy and the second a 48 year-old male with a retracted end colostomy. Both patients underwent significant emergency peristomal debridement and in both cases the commercial device was deployed to intubate the stoma. VAC foam and standard adhesive dressings were used to form a quality seal and the pressure set to 125mmHg. In both cases near complete healing was achieved to the point that standard stoma bags and management could be used.

Conclusion: This is the first description of the use of an isolation device in complex stoma associated wounds. We have found the Fistula Funnel to be safe in this context.

Keywords

VAC, Open abdomen, Wound management, Stoma, Technical note

Article Details

Introduction

Stoma formation is common in colorectal surgery - between January 2019 and January 2020, 218 stomas (ileostomies and colostomies) were formed in our Tertiary Colorectal Referral Centre. Routine stoma management is straightforward for the patient and clinician however 37 of our cases were defined as complex – In our experience we define this as cases requiring more than 4 daily stoma bag changes (high output), necessitates use of adjuncts (dehiscence) and an extended stoma-related stay of more than 10 days. Among the most challenging cases are stoma-associated wound complications. These can be devastating for the patient and present unique management challenges [1-3].

Complicated stomas are more prevalent in patients with obesity, those with diverticular or colorectal cancer aetiology, and in those requiring an emergency operation [4,5].

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been described for many years [6] and is supported in the UK for use on abdominal wounds by NICE [7]. Stomas with associated surrounding wounds share characteristics with matured, epithelised enterocutaneous fistula (ECF) and a recent review on NPWT specifically for use on ECF considered it safe with median closure rates of abdominal wounds of 64.6% [8]. Despite this, NPWT has been found to be less effective where fistula mucosa is visible or a clear tract exists – with poorer closure rates [9], suggesting the need for outlet intubation and isolation in these cases [10].

Outlet intubation and isolation involves temporary instrumentation the stoma outlet for drainage purposes and physical separation of the ECF or stoma from the surrounding wound. This enables drainage of effluent away from the wound dressing and separate to the NPWT system. Various temporary or makeshift methods of isolation have been described previously for ECF effluent management [11-13], with mixed results. Crucially in ECF the ultimate goal of conservative management is spontaneous closure, whereas the objective with stomas-associated wounds is a functioning, well-protected ostomy. Stoma-associated wounds therefore must have effective intubation and isolation and require a more robust, ideally purpose built solution for effluent management.

Commercial fistula intubation and isolation devices such as the FISTULA FUNNEL® (KCL) [14] and the FISTULA ADAPTER® (PPM Fistelapater, PHAMETRA PPM MEDICAL GmbH, Herne, Germany)15,16 have been used safely and effectively alongside NPWT on patients with ECF, but to date there has been no published description of use of a commercial fistula isolation device on a stoma complicated by wound dehiscence or breakdown.

We describe two cases from our unit, one ileostomy- and one colostomy-associated wound complications, where the FISTULA FUNNEL® was deployed successfully.

Technique

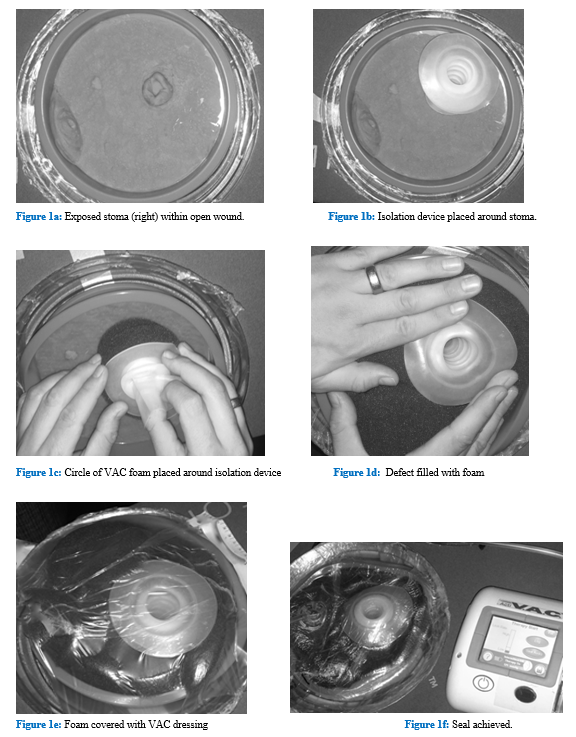

First, the stoma practitioner intubates the exposed stoma (Figure 1a) by placing the Fistula Funnel into the exposed enteral or colonic serosa (Figure 1b). Second, the stoma is isolated with a ring of non-adhesive dressing, in our case SILFLEX®. Third, foam is cut and placed around the isolation device (Figure 1c) and then the remaining defect is filled (Figure 1d). Finally, the defect is covered in transparent adhesive NPWT tape (Figure 1e) and a seal is achieved with 125 mmHg of continuous pressure (Figure 1f).

Case 1

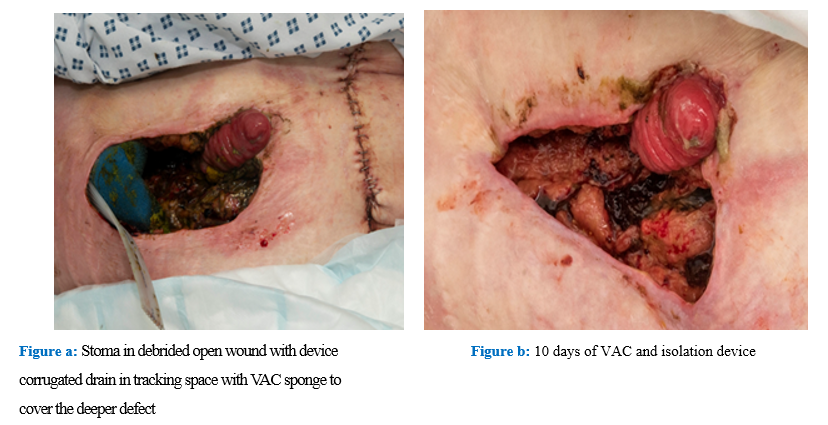

An 88-year-old woman with obesity, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and an open right hemicolectomy for bowel cancer 10 years previous was admitted with adhesional small bowel obstruction. After a failed trial of conservative management, she underwent laparotomy, division of adhesions and formation of loop ileostomy. She was extubated immediately post-operatively but persistently hypotensive despite appropriate fluid resusitation and required inotropic support. The ileostomy retracted with the afferent loop partly draining into the subcutaneous space, causing superficially spreading infection and later tissue breakdown. She thus underwent peristomal debridement. A large area lateral to the stoma was debrided and sheath exposed, further laterally into the right flank an abscess cavity was idenfied, drained and packed with NPWT foam and a corregated drain. Given her co-morbidity, frailty and high peri-operative risk, the decision was made against further operative interventions and therefore the intubation, isolation and NPWT conservative dressing technique was applied (Figure 2a). Dressing changes were performed every 36-48 hours with oral morphine sulphate analgesia administered prior to each change.

After 10 days of therapy, the defect was smaller and granulation tissue had started developing (Figure 2b). Most importantly we were able to successfully isolate enteral effluent away from the deeper wound avoiding contamination. There was extensive input from the dieticians and she was initially put on bowel rest with total parental nutrition (TPN) in order to reduce the stoma affluent.

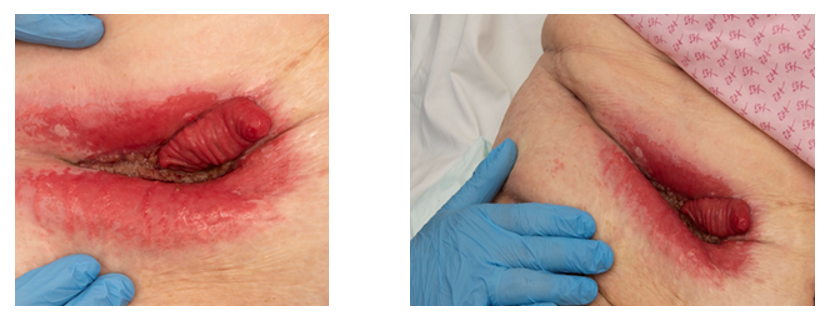

After one month of our technique the cavity had almost completely closed leaving only moderate irritation to the skin (Figure 3). From this point she was managed using simple stoma bags and a build-up base plate device. She was discharged home once safely able to self-manage the stoma.

Case 2

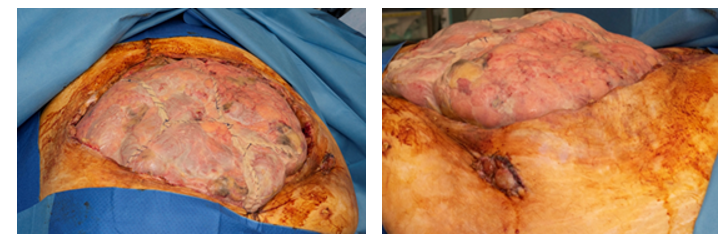

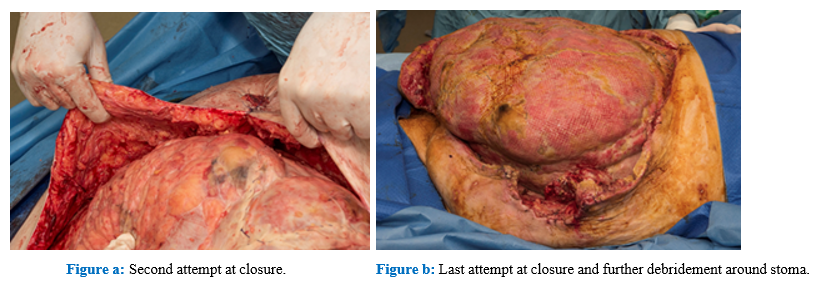

A 48-year-old male with obesity and hypertension underwent laparoscopic low anterior resection and primary anastomosis for rectal cancer. Post-operatively he developed an anastomotic leak and rapidly deteriorated, thus returning to theatre for emergency laparotomy, anastomotic take down and formation of end colostomy. The abdomen was left open with a temporary abdominal closure device. He was admitted to intensive care intubated and ventilated, where he required significant ionotropic support. On day 4 he returned to theatre - closure was not deemed possible, even with component separation and the patient instead underwent further debridement of necrotic tissue surrounding the retracted end colostomy and the abdomen left open this time with the cover of a patchwork of vicryl mesh (Figure 4). Further relook and consideration of closure were performed on day 7 (figure 5b), his stoma was initially sited well away from the wound edges, but after debridement was found to be in close proximity to the wound and significantly retracted.

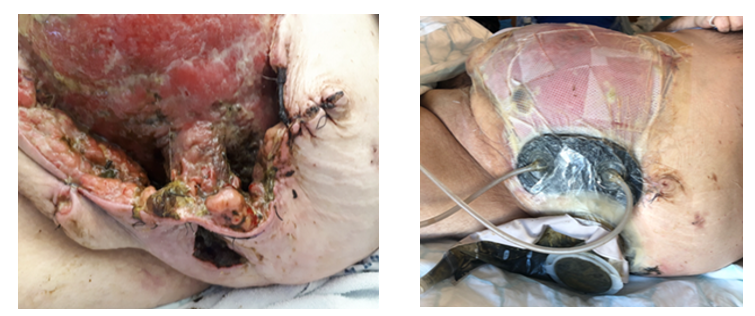

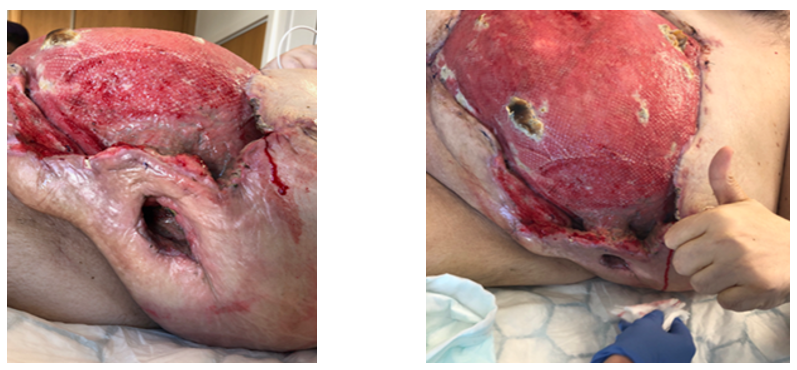

On day 10 we applied our intubation, isolation and NPWT technique with non-adhesive dressing to the abdominal wound. Once more dressing changes were performed every 36-48 hours and inhaled nitric oxide analgesia was administered. Laxatives were used to keep the stoma effluent loose enough to pass through the cut tapered end of the intubation device. Bedside dressing changes were performed every 36 hours (Figure 6). On day 17 granulation tissue began to form in the wound bed (Figure 7), and the stoma retraction was improving, with the lumen now identifiable. The gentleman was improving systemically and he was weaned off inotropic support.

Significant input was sought from the multidisciplinary team throughout admission. Intensivists oversaw the patient’s initial care. Dieticians facilitated initial TPN to enable bowel rest. Stoma and tissue viability nurses worked alongside the advanced nurse practitioner to facilitate timely and effective dressing changes. Plastic surgeons were heavily involved although by the final pre-discharge wound review on day 30 it was felt the wound was unsuitable for grafting thus conservative management would continue. The patient was transitioned onto oral morphine sulphate analgesia for dressing changed and then safely discharged on day 37 with ongoing community conventional dressings as the stoma. At this point the ostomy was surrounded by healthy skin and could be managed with a simple stoma bag (Figure 8).

Discussion

Management of ECF or stoma-associated wound complications is uniquely challenging for the clinical team and the patient [17]. These conditions are also a major resource burden, with extended length of stay and inflated associated costs for bed days and dressings [18].

NPWT is a recognised method of effective conservative management of ECF and stoma-associated wound complications alike. Generating effective NPWT with a quality seal and minimal effluent involvement is challenging with matured ECF or ostomy and thus intubation and isolation of the tract is recommended.

Prior to the introduction of commercial devices [14,16], makeshift low-cost intubation options have been utilised including a Jackson-Pratt drainage system [19], Malecot catheter [20], cuffed endotracheal tube [20] and foley catheter [22]. Various methods have also been deployed to isolate the stoma or enterocutaneous fistula - including stoma paste [11,12], Mepitel sling [3] and a sutured makeshift plastic silo [13].

We have found the use of commercial, purpose built intubation device FISTULA FUNNEL®, to be straightforward and time-sparing. Alongside isolation with non-adherant dressings and NPWT we have found this technique to provide impressive results in otherwise unmanageable ileostomy- or colostomy-associated wounds.

Conclusions

We would recommend the use of the FISTULA FUNNEL® devices alongside isolation and NPWT for management of stoma-associated complex wounds. There is a need for further work of the subject of peristomal wounds specifically as they posses unique characteristics and challenges, not all of which are shared with the management of ECF.

Author contributions

All authors contributed to this paper. N Browning created the technique. Material preparation, data collection and interpretation was performed by N Browning and M Okocha. The first draft of the manuscript was written by M Okocha and M Doe and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

No funding was granted or applied for in the preparation of this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Consent to publish

Patients signed informed consent regarding publishing their data and photographs.

Data statement

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

- Bilgin IA, Bas M, Demir S, et al. Management of Complicated Ostomy Dehiscence: A Case Study. J Wound, Ostomy Cont Nurs (2020).

- Zanella S, Di Leo A. Use of Vacuum-Assisted Closure in the Management of Colostomy. Surg Infect Case Reports 1 (2016): 165-168.

- Crick S, Roy A, MacKlin CP. Stoma dehiscence treated successfully with VAC dressing system. Tech Coloproctol 13 (2009): 181.

- Shabbir J, Britton DC. Stoma complications: a literature overview: Stoma complications. Colorectal Dis 12 (2010): 958-964.

- Cottam J, Richards K, Hasted A, et al. Results of a nationwide prospective audit of stoma complications within 3 weeks of surgery. Colorectal Dis 9 (2007): 834-838.

- Webb LX. New techniques in wound management: vacuum-assisted wound closure. J Am Acad Orthop Surg (2002).

- National institute for health and care Interventional procedure consultation document Transanal total mesorectal excision of the rectum 2 (2014): 1-8.

- Misky A, Hotouras A, Ribas Y, et al. A systematic literature review on the use of vacuum assisted closure for enterocutaneous fistula. Color Dis 18 (2016): 846-851.

- Gunn LA, Follmar KE, Wong MS, et al. Management of enterocutaneous fistulas using negative-pressure dressings. Ann Plast Surg (2006).

- Brindle CT, Blankenship J. Management of complex abdominal wounds with small bowel fistulae: Isolation techniques and exudate control to improve outcomes. J Wound, Ostomy Cont Nurs (2009).

- Timmons J, Russell F. The use of negative-pressure wound therapy to manage enteroatmospheric fistulae in two patients with large abdominal wounds. Int Wound J 11 (2014): 723-9.

- D’Hondt M, Devriendt D, Van Rooy F, et al. Treatment of small-bowel fistulae in the open abdomen with topical negative-pressure therapy. Am J Surg 202 (2011): e20-24.

- Subramaniam MH, Liscum KR, Hirshberg A. The Floating Stoma: A New Technique for Controlling Exposed Fistulae in Abdominal Trauma. J Trauma (2002).

- Heineman JT, Garcia LJ, Obst MA, et al. Collapsible Enteroatmospheric Fistula Isolation Device: A Novel, Simple Solution to a Complex Problem. J Am Coll Surg 221 (2015): e7-14.

- Jannasch O, Lippert H, Tautenhahn J. Ein neuer Adapter zur Versorgung von enteroatmosphärischen Fisteln beim offenen Abdomen. Zentralblatt fur Chir - Zeitschrift fur Allg Visz und Gefasschirurgie 136 (2011): 585-589.

- Wirth U, Renz BW, Andrade D, et al. Successful treatment of enteroatmospheric fistulas in combination with negative pressure wound therapy: Experience on 3 cases and literature review. Int Wound J 15 (2018): 722-730.

- Wainstein DE, Fernandez E, Gonzalez D, et al. Treatment of high-output enterocutaneous fistulas with a vacuum-compaction device. A ten-year experience. World J Surg 32 (2008): 430-435.

- Pedro GRT, Kenji I, Joseph D, et al. Enterocutaneous fistula complicating trauma laparotomy: A major resource burden. American Surgeon 75 (2009): 30-32.

- Stremitzer S, Dal Borgo A, Wild T, et al. Successful bridging treatment and healing of enteric fistulae by vacuum-assisted closure (VAC) therapy and targeted drainage in patients with open abdomen. Int J Colorectal Dis 26 (2011): 661-666.

- Ramsay PT, Mejia VA. Management of enteroatmospheric fistulae in the open abdomen. Am Surg. 2010;76(6):637–9.

- Zanella S, Di Leo A. Use of Vacuum-Assisted Closure in the Management of Colostomy. Surg Infect Case Reports 1 (2016): 165-168.

- Bobkiewicz A, Walczak D, Smoliński S, et al. Management of enteroatmospheric fistula with negative pressure wound therapy in open abdomen treatment: a multicentre observational study. Int Wound J 14 (2017): 255-264.

Impact Factor: * 4.2

Impact Factor: * 4.2 Acceptance Rate: 72.62%

Acceptance Rate: 72.62%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks