Perceptions and Experiences of Rare Diseases among General Practitioners: An Exploratory Study in NI

Julie McMullan1, Ashleen L Crowe1, Taylor McClenaghan1, Helen McAneney1,2, Amy Jayne McKnight1*

1Centre for Public Health, School of Medicine Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Clinical Science Block A, Grosvenor Road, Belfast, BT12 6BA, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom

2Northern Ireland Rare Disease Partnership, 2 William Street, Newtownards, BT23 4AH, United Kingdom

*Corresponding Author: AJ McKnight, Centre for Public Health, School of Medicine Dentistry and Biomedical Sciences, Institute of Clinical Science Block A, Grosvenor Road, Belfast, BT12 6BA, Northern Ireland, United Kingdom.

Received: 06 March 2023; Accepted: 12 April 2023; Published: 09 June 2023

Article Information

Citation: Julie McMullan, Ashleen L Crowe, Taylor McClenaghan, Helen McAneney, Amy Jayne McKnight. Perceptions and Experiences of Rare Diseases among General Practitioners: An Exploratory Study in NI. Archives of Clinical and Medical Case Reports. 7 (2023): 248-256.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Objective: To gain an understanding of GP’s perception and experience of rare diseases.

Design: This is an exploratory study with GPs from Northern Ireland.

Setting: An online survey was hosted within Smart Survey, available for 6 weeks in early 2019, which queried: GPs career to date, interaction with rare disease patients, challenges faced, the exchange of information with patients, priorities for the future, support for such patients and finally training. The survey contained open-ended and closed-ended questions and both qualitative (narrative) and quantitative analyses were carried out.

Participants: Sixty-six GPs engaged with the survey with 15 completing the survey.

Results: Many frustrations were mentioned by GPs when caring for such patients including finding a diagnosis, lack of specialist services and lack of awareness of rare diseases. Seventy-nine percent of GPs responding did not feel adequately trained to care for patients with a rare disease, while 93% were interested in undertaking training to enable them to improve their care for rare disease patients.

Conclusions: More effective and convenient ‘rare disease’ focused training programs would help GPs manage patients with rare diseases. Enabling efficient, effective communication between GPs and individual medical specialists is of paramount importance to give GPs access to information on how to effectively manage patients living with a rare disease. Awareness should be raised for effective support mechanisms such as charities and support groups for rare disease patients.

Keywords

<p>General Practice; Rare Disease; Survey; Online; Qualitative</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

A rare disease is defined by the European Medicines Agency as a ‘life-threatening or chronically debilitating’ condition which affects no more than 5 per 10000 people in the EU [1]. In recent years rare diseases have been acknowledged as a major public health concern [2]. There are more than 10,000 known rare diseases, affecting around 350 million people worldwide, 3.5 million in the United Kingdom (UK) and 110,000 in Northern Ireland (NI) [3, 4]. Many of these diseases are unknown to the majority of healthcare professionals (HCPs) [5], and managing rare diseases in clinical practice is difficult due to their diversity, their complexity, and lack of dedicated rare disease training [6].

Due to the low prevalence and lack of expertise for many conditions, patients living with a rare disease are often compelled to become knowledgeable about their own disease. They become ‘expert patients’ alongside their carer(s) as they seek an empowering and collaborative approach with their clinicians [7-10]. This is a shift from the traditional patient-doctor relationship with each participant revising their role and expectations [10]. An accessible, proactive General Practitioner (GP) relationship may help reduce many of the negative aspects of living with a rare disease [11] as well as lowering medical costs and minimizing misuse of medical service (e.g. fewer diagnostic tests), by adopting a patient centered approach to care [12, 13].

Previous research indicates that those with a rare disease experience difficulties finding reliability, empathy, relevant knowledge, adequate communication, and understanding from the HCPs they encounter [9, 14-16]. GPs play an important role in healthcare delivery for people living with a rare disease and their families by increasing familiarity with the disease and the impact it is likely to have on the patient and their support network [2, 7, 17]. GPs are often the first point of contact for those presenting with symptoms and when diagnosed, rare disease patients will attend a GP between visits to specialist services. GPs may take an active role in developing and implementing appropriate care plans and case coordination for rare disease patients [18].

The Northern Ireland Rare Disease Implementation Plan (2015) [19] recognised that GPs need further training to facilitate effective diagnosis and intervention to treat people with rare diseases, and that protocols for those who have no diagnosis or are at potential risk of having a rare disease should be put in place. In the NI Rare Disease Action Plan 2022/2023 improved training for healthcare professionals and actions to improve diagnosis in NI were again stated [4]. The UK strategy for Rare Diseases [20] and UK framework for Rare Diseases [21] emphasized the need for improvement of the coordination of care, diagnosis, treatment and patient empowerment.

The exploratory approach undertaken in this study explored GPs perceptions and experiences of rare diseases within a GP population from NI.

2. Material and Methods

An exploration was conducted of the experience of GP’s interaction with patients living with a rare disease(s) across NI via an online survey. A primarily qualitative approach was chosen [22] for this study as the aim was to gain insight into the perceptions and experiences of GPs regarding rare diseases. ‘Qualitative research aims to understand the behaviour and beliefs, identify processes, and to understand the context of people’s experiences’ [22]. This paper has been written in accordance with the guidance for reporting qualitative research as outlined by O’Brien et al. (2014) [23]. A simple narrative analysis was conducted with the responses provided in the free text boxes. The closed questions of the survey were summarized by quantitative analysis.

Ethical approval was provided by the Faculty of Medicine, Life and Health Sciences, Queen’s University of Belfast (QUB), (reference 18.47v3). Results were collated anonymously and used to evaluate current knowledge of GPs and identify where additional resources are needed to better support them.

An online survey was hosted within Smart Survey (www.smartsurvey.co.uk) [24] [from mid-January 2019 for 6 weeks] with two sections and 26 questions (Supplementary file 1). The survey was constructed using an iterative approach with input from the Northern Ireland Rare Disease Partnership (NIRDP), the national charity for rare diseases in NI [25] and was uploaded to the Smart Survey platform [24] after being piloted with the NIRDP. The survey queried: GPs career to date, interaction with rare disease patients, challenges faced, the exchange of information with patients, priorities for the future, support for such patients and finally training. The survey was comprised of closed and open-ended questions and respondents had the option to save and complete the questions at a later date. The survey did not focus on a specific rare disease but asked generally about ‘rare diseases’ as a group of conditions.

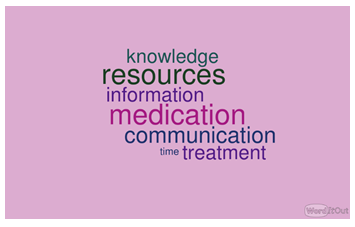

A web link to the survey and participant information leaflet were advertised via a variety of online platforms including the NIRDP website (www.nirdp.org.uk) [25]. The survey link was posted on Twitter on a recruitment notice on the NIRDP and QUB Twitter pages. It was also submitted for inclusion in a NI Royal College of General Practitioners newsletter, and QUB Commas (www.qub.ac.uk/sites/StaffGateway/RoundUp/) [26] newsfeed. To be eligible to participate, potential respondents had to be a GP currently working in NI. Smart Survey [24] was used to generate tables and charts to add demographic and statistical information to the study. Worditout.com [27] was used to create a word cloud (Figure 1) incorporating the views taken from question 12 of the survey. It illustrates the biggest challenges GPs face when caring for rare disease patients.

Figure 1: The biggest challenges GPs face when dealing with a rare disease patient.

3. Results

3.1 Respondent characteristics

Sixty-six GPs participated in the survey with 15 proceeding through questions in the survey and pressing the ‘submit’ button. There are 321 GP Practices in NI and a total 1932 GPs are registered on the performers list [28]. 1 in 17 people will be affected by a rare disease at some point in their lives. This amounts to more than 110,000 people across Northern Ireland [25]. The demographics of those who responded fully are displayed in Table 1. 73.3% of respondents were female, over half were from Northern Ireland (53.3%) and 46.2% had been working as a GP for 0-10 years at the time of the survey.

|

Characteristic |

Sub-groups |

% |

Frequency |

|

Gender |

Female Male |

73.3 26.7 |

11 4 |

|

Age range |

25-34 35-44 45-54 55+ |

26.7 33.3 13.3 26.7 |

4 5 2 4 |

|

Ethnicity |

British Northern Irish Irish Any other white British background |

26.7 53.3 13.3 6.7 |

4 8 1 2 |

|

Years working as a GP |

0-10 years 11-20 years 21-30 years 31+ years Prefer not to say |

46.2 23.1 7.7 23.1 - |

6 3 1 3 2 |

|

Number of GPs within their practice |

3 4 5 6 7 Prefer not to say |

21.4 28.6 28.6 14.3 7.1 - |

3 4 4 2 1 1 |

|

Location of the GP practice |

Urban Rural Prefer not to say |

57.1 42.9 - |

8 6 1 |

Table 1: Demographics of respondents (n=15).

3.2 GP interaction with rare disease patients

Ninety-three percent (n=13) of GPs had experience of rare disease patients in their career. When asked how often they encounter an individual with a rare disease, the responses were, 8% (n=1) ‘once a week’; 39% (n=5) ‘every month’, 31% (n=4) ‘every six months’ and 23% (n=3) said ‘every year’. Forty-six percent (n=6) of GPs surveyed said they occasionally/frequently encounter patients attending clinic with information about their rare disease / potential diagnosis / treatment options. When asked to briefly outline their interaction with rare disease patients various responses were given including, ‘Some know lots about their condition, some not so much. I have told patients I don’t know anything about their condition in the past’ and ‘As the GP my role frequently involves being central to the co-ordination of their care’. Sixty-seven percent (n=8) of GPs reported that they do not normally discuss genetics with rare disease patients. Sixty-nine percent (n=9) of GPs surveyed said they believe they can learn from rare disease patients. Specifically, they stated these patients provide ‘useful insights’, have remarkable ‘coping abilities and humanity’, unique ‘knowledge of diseases’ and they can learn from their diagnosis journey for future patients. Fifty-four percent (n=7) of GPs believe that the expectations a rare disease patient has of them is achievable. The remaining 46% (n=6) provided various reasons as to why they felt otherwise including: lack of resources, inadequate communication from secondary care, lack of understanding and confidence.

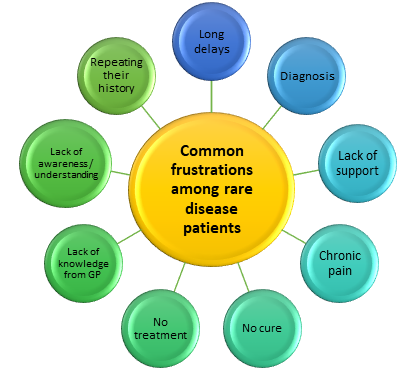

GPs described what they perceived to be the many common frustrations among rare disease patients (Figure 2) These included: long delays, accessing services, finding a diagnosis, getting practical support, lack of follow up, lack of access to specialist services, a benefits system that cannot deal with the patients with complex conditions, distances to clinics, poor transport services, frustration, chronic pain, feeling left behind due to lack of understanding of their condition, having to repeat their history to every doctor and lack of awareness of rare diseases.

Figure 2: The common frustrations among rare disease patients, as perceived by GPs.

3.3 Training

Seventy-one percent (n=10) of GPs said ‘rare disease’ was not included as a topic in their training to become a GP and none of them had undertaken any rare disease training since working as a GP. When asked if they felt they had been adequately trained to care for patients with a rare disease, 79% (n=11) of GPs stated ‘no’. Ninety three percent (n=13) of GPs surveyed in our study said they would be interested in undertaking training to enable them to improve their care for rare disease patients. Several suggestions were made as to how this training should be delivered including practice-based learning sessions, workshop, online module and face-to-face training.

3.4 Support

Fifty-seven percent (n=8) of GPs surveyed had never referred a patient to a rare disease charity. 64% (n=9) of GPs were unaware of the NIRDP, [25] the umbrella charity for rare diseases in NI. Eighty-six percent (n=12) of GPs felt there is not sufficient care/support available for those with a rare disease. When asked what more they feel could be done through charity/support groups, responses included: funding, support/specialist nurses, increased awareness and more online networking.

The word cloud (Figure 1) illustrates the biggest challenges GPs face when caring for rare disease patients. Many challenges were highlighted including: finding information, poor communication from secondary care, time constraints, lack of knowledge / resources, relying on the patient to be well informed about their condition, access to specialists and getting medication right. Despite very limited capacity, a GP stated that, ‘Frequently there are no easy answers so the best thing is to spend time with the patient listening to concerns and offering support’.

3.5 Information

When GPs were asked if they encourage rare disease patients to research their condition for themselves, 85% (n=11) said they do. Thirty-nine percent (n=5) stated that patients normally bring information about their rare disease to appointments. Forty-six percent (n=6) of GPs surveyed said they do not normally give rare disease patients any literature to take away. Those that do said they get literature from the Internet, ‘recognised websites’, web mentor and Patient UK [29]. ‘Recognised websites’ was not elaborated upon. One GP stated, ‘Normally the patient knows more than I do…’.

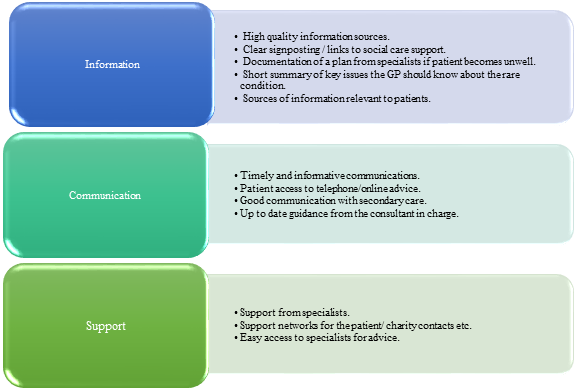

Figure 3 displays the top priorities that GPs suggested would help most in their interaction with patients and / or other HCPs about rare disease(s).

Figure 3: Top priorities that would help GPs most in their interactions with patients / other healthcare practitioners regarding rare disease(s).

3. Discussion

Our research identified the need for appropriate support to be developed to enable GPs to more effectively identify and care for those living with a rare disease. Training focusing on caring for rare disease patients was specifically mentioned by GPs with many never having received appropriate training as part of their vocational qualification. Although training on specific rare diseases is not a valid use of their time, it would be useful and possible that they have received more general training on low incidence conditions. There was a desire for GPs to know more and to gain confidence when making decisions for this patient group’s care. For many GPs the concept of genetics is currently viewed as an element of care beyond their remit; raising awareness through training would enable them to appreciate the responsibility their specialty has within Primary Care. Currently there is no Royal College of General Practitioners e learning which focuses on rare diseases. Given the role Genomics plays in many conditions seen in primary care every day, this is a much needed area for development to link GPs to relevant national information and support sources.

An awareness around the resources for rare disease patients available online would be beneficial for GPs. Having access to such resources would enable them to provide patients with reliable information and thereby avoid endless hours of trawling the internet or the risk of lead them down the wrong path. It was also suggested that the use of databases such as Orphanet [30], OMIM [31] and Gene Reviews [32] may aid the GP in directing the patient to the appropriate specialist or clinic to investigate further.

Through this study it was acknowledged that GPs share a unique relationship with rare disease patients and that both parties can learn much from one another. By appreciating the value each can bring the level of care can be greatly enriched.

Previous research has indicated that a lack of knowledge among GPs causes feelings of inadequacy when caring for rare disease patients [5]. It therefore seems crucial that training is considered as a priority to enable GPs to more confidently care for this unique group of patients. In agreement with the current study, GPs have previously reported their desire for additional training in this field [18, 33]. Knight and Senior (2006) [11] highlighted the lack of a defined role for the GP when dealing with patients with a rare disease and their families, as well as a lack of available support and resources for GPs. Although individually rare, collectively rare diseases affect a significant proportion of the general population [34]. This means, most physicians will face the diagnosis or treatment of a rare disease at some point in their professional lives [33]. Given this low level of interaction it is interesting that 93% of GPs surveys in our study would be interested in undergoing training in the field of rare diseases. A study conducted by Hariyan et al. (2020) found that increased training for HCP via workshops and lectures improved their rare disease knowledge [35]. Research conducted in Poland among medical students at a university reported that 95.4% of respondents perceived their knowledge about rare disease as insufficient or very poor and 92.2% did not feel prepared for caring for rare disease patients (36). Harivan et al. (2020) suggests it would be beneficial to commence rare disease specific training at an early stage in medical training. A lack of awareness of rare diseases among GPs has been highlighted in previous research [7, 37, 38].

A recent study by Byrne et al. (2020) reported that few GPs are aware of or have used Orphanet (a primary source of information on rare disease) [37]. Given that the current study found that GPs turn to the Internet as a source of information for rare disease, it is imperative they are aware of reliable sources to depend on and enhance their knowledge. The Internet has been shown to play a significant role to source clinical information [17, 38] however patients have reported that GPs frequently give incorrect information [17].

Domaradzki and Walkowiak (2019) concluded that many medical students feel it is the responsibility of geneticists and pediatricians to be specifically educated and trained in the field of rare disease [36]. Again, this highlights the need for early training interventions to raise awareness of the importance of understanding the needs of rare disease patients. Genomic medicine is being rolled out across all medical specialties in the UK and therefore rare diseases are no longer the domain of specialist genetic services. Smit et al. (2019) found that GPs believe that genomic risk may become a responsibility within primary care and they recommended a shared decision making approach to guide the testing process [39]. Many adults are living with a rare disease that is not diagnosed in childhood [40].

A study in Australia conducted a survey to investigate if the healthcare needs of rare disease patients are being met. Almost three quarters of those surveyed reported having received no or not enough information at the time of diagnosis [41]. This complements the current study where almost half of GPs said they do not give patients information to take away with many encouraging patients to research their condition for themselves. Similarly McMullan et al. (2020) found that rare disease groups expressed their desire for HCPs to interact with rare disease group’s information resources by joining consortiums, passing on relevant leaflets, as well as the usual channels [42].

Our survey found that 57% of GPs did not refer their patient to a rare disease charity and 64% were not familiar with the only national charity for rare diseases across NI, NIRDP. Previously Anderson et al. (2013) discovered that 87% (n=26) of patients wished to receive information on support groups, with only 43% (n=13) receiving this [43]. Creating awareness among GP communities in NI and worldwide of the charities and support groups available is key as rare disease patients find charities to provide continued support and may enable them to communicate with others who live with the same condition. The knowledge gap in rare diseases is compounded by the limited availability of information and official guidelines [44].

Our study highlighted the fact that GPs and rare disease patients share a unique relationship in which patients often take on the role as the expert. As stated previously, 69% of GPs surveyed believe they can learn from rare disease patients stating, ‘One gave me a short story written by a sufferer which was a real eye opener and very helpful’ and ‘They may have had difficulty in obtaining a diagnosis so hearing about how this came about is helpful for future pattern recognition’. The two parties complement one another as HCPs have valuable insight into how a rare disease is exhibited, what medications do and do not work, and the true burden of the disease [45]. HCPs may also identify areas for additional support, which the patient may be unaware of [46]. Further research would be of value focusing solely on GPs rather than the wide group of HCPs.

The literature shows how online databases such as Orphanet may be of use to GPs in order to provide a diagnosis for the rare disease patients [2, 17]. This may decrease the diagnostic delay frequently experienced and provide reliable information to GPs surrounding the diseases that they experience. Promoting awareness of the different online resources available may empower GPs to make an accurate diagnosis and provide support to their patients. One GP stated, ‘We are on a shared journey to know more’ when talking about meeting the expectations of rare disease patients.

This study has acknowledged the difficult role GPs find themselves in when caring for patients with a rare disease. Lack of training and reliable information make providing an adequate level of care extremely challenging. Through this study the need for better training has been identified with 93% of GPs surveyed stating their desire to know more and build upon their current knowledge. Incorporating this training at an early stage in GP training appears to be the most effective and highlights the importance of being aware of this patient group and their unique needs. Awareness of rare diseases in general should be raised among the GP population with a particular emphasis on the resources available to help them as HCPs but also to benefit patients by providing them with reliable sources of information and perhaps connecting them to others living with the same condition elsewhere in the world. The Royal College of General Practitioners in partnership with Health Education England Genomics Education Programme has developed the Genomics Toolkit [47]. This is used to support increasing understanding, raise awareness of Genomics Medicine and support primary care with increased knowledge of how Genomics can contribute to improving patient care in a ‘Genomics era’. Raising awareness of this resource would be helpful alongside developing national specific resources. Furthermore, the use of online databases for rare disease patients enhances the care provided and can help to reduce the diagnostic odyssey that many patients find they living in.

4. Strengths and Limitations of this Study

- The use of an online survey made this research more accessible for a wide audience to access remotely.

- This research could be a useful starting point for further complementary studies using focus groups and also directly involving patients.

- In this study, data were collected from a relatively small population group, which none-the-less was sufficient to confirm similar issues were consistently highlighted. The survey was anonymous so we did not follow-up with participants to explore why more started the survey than answered all of the questions.

- The survey was promoted via email and Twitter; using other methods of dissemination may have helped to generate more responses. To gather more in-depth responses in the future it would be interesting to build upon this research by working with the Royal College of General Practitioners to conduct interviews with GPs to gain a greater insight into their views which is difficult to gather via a survey with predefined questions.

- Many consistently reported problems were described by GPs when caring for patients with a rare disease, including finding a diagnosis, lack of specialist services and lack of awareness of rare diseases, leading to several solutions being proposed such as ‘rare disease’ focused training enabling more efficient, effective communication, and raising awareness of existing community support.

5. Conclusion

New insights have been added to the area of rare disease care and the need for training, support and more awareness have been highlighted. As echoed in previous research within our research team, this study recognizes the importance of listening to all voices within the rare disease community [42, 48]. The surveys provided insight into the interaction GPs have with rare disease patients in NI and have identified where more support is needed to enable GPs to carry out this challenging role.

There is a gap in the information and training available to GPs and this issue needs to be combatted to satisfy the aims of the Northern Ireland Rare Disease Implementation Plan 2015 and more recently the NI Rare Diseases Action Plan 2022/2023 [4, 19] and therefore a clear area to target would be accessible training. GPs require more effective and convenient training programs and a universal web-based resource would be favorable among the GP communities in NI who are searching for information online. Easing communication between GPs and hospital specialists is of paramount importance to give GPs access to the best information on how to treat their rare disease patients. Awareness should be generated to existing charities and support groups for rare disease patients as this eases the experience for the patient and removes pressure from the GP. A quick reference guide for rare disease was recently developed to help support rare disease management in general practice [17]. A better infrastructure should be introduced in order to allow smooth communication and to keep records of up to date information and care plans accessible to all involved in the patients care.

It is evident that GPs do their best to care for rare disease patients in what are often very difficult circumstances with no hope of effective treatment or cure, minimal (if any) local specialists to rely on, and sub-optimal training to equip them with tailored ways to effectively manage each rare disease.

This research could be a useful starting point for further complementary studies using focus groups and also directly involving patients. Using alternative methods to reach a wider audience and therefore a more representative sample could be considered in future research. For example, actively contacting GPs of rare disease patients through patient associations.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by an award from the NI Public Health Agency and the Medical Research Council – Northern Ireland Executive support of the Northern Ireland Genomic Medicine Centre though Belfast Health and Social Care Trust. AC is a recipient of a PhD studentship from the Department for the Economy NI.

Competing Interests Statement

The authors have no competing interests to declare. AJM is a former board member and HM an existing board member of the NIRDP. An abstract entitled ‘Perceptions and experiences of rare disease among the General Practitioner (GP) population in Northern Ireland’ was presented at BJGP conference in 2019; British Journal of General Practice 2019; 69 (suppl1): bjgp19X703637.

DOI: https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp19X703637

Author’s Contributions

AJM conceived of the project, designed the survey and drafted the manuscript. JM designed the survey, analyzed the data, and drafted the manuscript. TM collected the survey data and analyzed the data. AC and HM helped with data collection, and AC assisted with drafting the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Data Sharing Statement

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due as they contain potentially identifiable information but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Patient and Public Involvement Statement

The survey was constructed using an iterative approach with input from the Northern Ireland Rare Disease Partnership (NIRDP), the national charity for rare diseases in NI.

Supplementary File

Supplementary file 1

- Template survey

- Figure 1

- The biggest challenges GPs face when dealing with a rare disease patient

- Figure 2

- The common frustrations among rare disease patients

- Figure 3

- Top priorities that would help GPs most in their interactions with patients / other healthcare practitioners regarding rare disease(s).

References

- European Union. Regulation (EC) N°141/2000 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 16 December 1999 on orphan medicinal products (2000).

- Boffin N, Swinnen E, Wens J, et al. General Practice Care for Patients with Rare Diseases in Belgium. A Cross-Sectional Survey. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15 (2018).

- Fu MP, Merrill SM, Sharma M, et al. Rare diseases of epigenetic origin: Challenges and opportunities. Front Genet 14 (2023): 1113086.

- Northern Ireland Rare Diseases Action Plan 2022/23 (2022).

- Balbi B, Vallese D, Chavannes N, et al. General practitioners and rare lung diseases: a task force for the development of rare lung diseases educational material. Breathe (Sheff) 12 (2016): 341-348.

- Baque M, Colineaux H, Dreyfus I, et al. Why is it so difficult for GPs to effectively manage patients with rare skin diseases? Presse Med 48 (2019): e382-e388.

- Elliott E, Zurynsk Y. Rare diseases are a ‘common’ problem for clinicians. Focus 44 (2015): 630-633.

- Zurynski Y, Deverell M, Dalkeith T, et al. Australian children living with rare diseases: experiences of diagnosis and perceived consequences of diagnostic delays. Orphanet J Rare Dis 12 (2017): 68.

- Budych K, Helms TM, Schultz C. How do patients with rare diseases experience the medical encounter? Exploring role behavior and its impact on patient-physician interaction. Health Policy 105 (2012): 154-164.

- Evans WR, Rafi I. Rare diseases in general practice: recognising the zebras among the horses. Br J Gen Pract 66 (2016): 550-551.

- Knight A, Senior T. The common problem of rare disease in general practice. MJA 185 (2006): 82-83.

- Epstein RM, Franks P, Shields CG, et al. Patient-centered communication and diagnostic testing. Ann Fam Med 3 (2005): 415-421.

- Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ 323 (2001): 908-911.

- Jeppesen J, Rahbek J, Gredal O, et al. How Narrative Journalistic Stories Can Communicate the Individual's Challenges of Daily Living with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Patient 8 (2015): 41-49.

- Greulich T, Ottaviani S, Bals R, et al. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency - diagnostic testing and disease awareness in Germany and Italy. Respir Med 107 (2013): 1400-1408.

- Crowe AL, McKnight AJ, McAneney H. Communication Needs for Individuals with Rare Diseases within and Around the Healthcare System of Northern Ireland. Frontiers in Public Health 7 (2019).

- Crowe A, McAneney H, Morrison P, et al. A quick reference guide for rare disease: supporting rare disease management in general practice. British Journal of General Practice 70 (2020): 260-261.

- Engel P, Bagal S, Broback M, etal. Physician and patient perceptions regarding physician training in rare diseases: the need for stronger educational initiatives for physicians The Journal of Rare Disorders 1 (2015): 1-15.

- Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety: Providing High Quality Care for People Affected by Rare Diseases - The Northern Ireland Implementation Plan for Rare Diseases Department of Health Social Services and Public Safety (2015).

- The UK Strategy for Rare Diseases Department of Health (2013).

- The UK Rare Diseases Framework. GOV.UK (2021).

- Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research. 3rd Edition ed: London Sage (2008): 31.

- O'Brien B, Harris I, Beckham T, et al. Standards for reporting qualitative research: a synthesis of recommendations Academic Medicine 89 (2014): 1245-1251.

- Smart Survey [Available from: www.smartsurvey.co.uk (2021).

- Northern Ireland Rare Disease Partnership (2021).

- Queen's University Belfast Communication - Staff Roundup (2021).

- Worditout.com (2021).

- HSC website (2022).

- Patient UK website (2021).

- The portal for rare diseases and orphan drugs (2021).

- A comprehensive, authoritative compendium of human genes and genetic phenotypes (2021).

- A knowledge database of genetic disorders (2021).

- Ramalle-Gomara E, Dominguez-Garrido E, Gomez-Eguilaz M, et al. Education and information needs for physicians about rare diseases in Spain. Orphanet J Rare Dis 15 (2020): 18.

- E, Lippi. G. Rare diseases: the paradox of an emerging challenge. Annals of Translational Medicine 6 (2018): 329.

- Hariyan T, Kinash M, Kovalenko R, et al. Evaluation of awareness about primary immunodeficiencies among physicians before and after implementation of the educational program: A longitudinal study. PLoS One 15 (2020): e0233342.

- Domaradzki J, Walkowiak D. Medical students' knowledge and opinions about rare diseases: A case study from Poland. Intractable Rare Dis Res 8 (2019): 252-259.

- Byrne N, Turner J, Marron R, et al. The role of primary care in management of rare diseases in Ireland. Ir J Med Sci 189 (2020): 771-776.

- Cullen R. In search of evidence: family practitioners’ use of the Internet for clinical information. J Med Libr Assoc 90 (2002): 370-379.

- Smit AK NA, Keogh L, Best M, et al. GP attitudes to and expectations for providing personal genomic risk information to the public: a qualitative study. BJGP Open 20 (2019).

- Europe ERD. Living with a rare disease (2021).

- Molster C, Urwin D, Di Pietro L, et al. Survey of healthcare experiences of Australian adults living with rare diseases. Orphanet J Rare Dis 11 (2016): 30.

- McMullan J, Crowe A, Bailie C, et al. Improvements needed to support people living and working with a rare disease in Northern Ireland: current rare disease support perceived as inadequate. Orphanet J Rare Dis 15 (2020).

- Anderson M, Elliott E, Zurynski Y. Australian families living with rare disease:experiences of diagnosis, health services use and needs for psychosocial support. Orphanet J Rare Dis 8 (2013).

- Stoller JK. The Challenge of Rare Diseases. Chest 153 (2018): 1309-1314.

- Annemans L, Ayme S, Le Cam Y, et al. Recommendations from the European Working Group for Value Assessment and Funding Processes in Rare Diseases (ORPH-VAL). Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 12 (2017).

- Babac A, Frank M, Pauer F, et al. Telephone health services in the field of rare diseases: a qualitative interview study examining the needs of patients, relatives, and health care professionals in Germany. Bmc Health Services Research 18 (2018).

- Royal College of General Practitioners - Genomics Toolkit (2021).

- McMullan J, Crowe A, Downes K, et al. Carer reported experiences: Supporting someone with a rare disease. Health and Social Care in the Community (2021): 1-12.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 75.63%

Acceptance Rate: 75.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks