Severe Immune-Related Cutaneous Vasculitis Induced by Osimertinib

Benoit Calderon, Léa Vazquez*

Sainte Catherine Institut du Cancer Avignon-Provence, Avignon, France

*Corresponding Author: Léa Vazquez, Sainte Catherine Institut du Cancer Avignon-Provence, 250 chemin des baigne-pieds, 84918 Avignon Cedex 9, France

Received: 19 May 2022; Accepted: 14 June 2022; Published: 12 July 2022

Article Information

Citation: Benoit Calderon, Léa Vazquez. Severe Immune-Related Cutaneous Vasculitis Induced by Osimertinib. Archives of Clinical and Medical Case Reports 6 (2022): 524-527

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Osimertinib is a third-generation epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)- tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) which is the current standard of care for first-line treatment of advanced EGFR+ Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer (NSCLC). The most common Osimertinib-related adverse events (AEs) are hematologic toxicity, rash, dry skin, and paronychia which are usually tolerable and manageable. Serious AEs occur infrequently and the etiopathogenesis of some remains unclear. We present a case of grade 3 cutaneous vasculitis induced by osimertinib in a Caucasian woman that required immunosuppressive therapy.

Keywords

<p>Osimertinib; Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor; Immunosup pressive Therapy; Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

The 2018 National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) Clinical Practice Guideline for NSCLC recommend EGFR-TKIs as first-line treatment for unresectable, EGFR mutation-positive, advanced NSCLC [1]. Osimertinib, a third-generation EGFR-TKI that targets T790M mutation, showed a longer Progression-Free Survival (PFS) than first generation EGFR-TKIs (gefitinib or erlotinib) when it was administered as first-line treatment, regardless of T790M mutation status [2, 3]. Moreover, the incidence of adverse events of grade 3 or higher among patients who received Osimertinib was similar to that among patients who received gefitinib or erlotinib, despite longer treatment exposure [2, 3]. All generations of EGFR-TKIs have similar side-effects profiles, although the frequency and severity of AEs vary by the respective drugs. Indeed, EGFR plays an essential role in epithelial maintenance and, therefore, EGFR-TKIs might impair epithelial cell growth and migration and alter cytokine expression, leading to the recruitment of inflammatory cells and consequent tissue injury. Rash, paronychia, and diarrhoea were the most common AEs reported with first and second-generation EGFR [4].

Infrequently, serious AEs, mainly drug-induced lung injury, occur with EGFR-TKIs and even call for dose reduction, treatment discontinuation, or pharmacotherapeutic intervention and hospitalisation. Although some studies seemed to suggest that cutaneous reactions may predict treatment efficacy, cutaneous reactions have a profound influence on patients’ quality of life and adherence to the treatment, and can, therefore, represent a barrier to oncologic treatment [5, 6]. Due to the higher selectivity to the mutated receptor, Osimertinib is associated with less severe gastrointestinal and skin toxicity compared with first and second-generation EGFR TKIs [7]. Rarely, dermatologic serious AEs can occur such as necrolytic migratory erythema, toxic dermal epidermolysis, transient acanthotic dermatosis, anaphylaxis, or vasculitis [8-10]. Drug-induced vasculitis reactions are defined as inflammatory vasculitis in which a specific drug is established as the causal agent. While rashes are common with EGFR-TKIs, vasculitis is very different from other hypersensitivity reactions. Vasculitis is characterized by histological evidence of blood vessel inflammation, often defined by a perivascular lymphocytic infiltration, which can lead to the thinning or rupture of the blood vessel wall [11]. We present a case of Osimertinib-induced grade 3 cutaneous vasculitis in a Caucasian woman.

2. Case Presentation

We describe the case of an 86-year-old non-smoker European

woman referred to our institution for a 60mm-tumoral mass in the right upper lobe of the lung associated with enlarged mediastinal lymph nodes, and bone, hepatic and adrenal metastases, revealed by a thoracic computed tomography (CT). There was no family history of cancer. She was never-smoker, but she relates second-hand smoke exposure. Patient physical examination revealed lumbar pain, a unilateral and diffuse increase in vesicular breath sounds over the right lung tissue and an ECOG Performance Status of 1. Bronchoscopy confirmed the tumor in the right upper bronchus, and a biopsy revealed lung adenocarcinoma with EGFR exon 19 mutation. Brain CT reveals no cerebral metastases but Thoracic-Abdominal-Pelvic CT shows bone metastases with a fracture of 7th thoracic vertebrae. The diagnosis of lung adenocarcinoma T3N2M1c clinical stage IVb was confirmed. As a first step, pain management is initiated with analgesic radiation therapy (8Gy 1fraction) on 7th thoracic vertebrae and algology consultation for the follow-up.

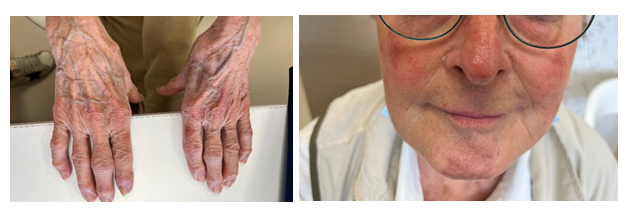

First-line treatment with Osimertinib (monotherapy 80mg/d) was initiated the day after radiation therapy. Nineteen days later, the patient is admitted in emergency for numerous skin lesions (necrotic purpura) suitable with cutaneous vasculitis (Figure 1a and 1b) with neither pain nor pruritus. Lesions are located on the nose, ears, face, tongue, palate, soles of the feet and hands, fingers of the feet and hands, knees, elbows, and shins. The lesions appeared successively for about a week. The patient reports chest pressure sensation and epistaxis, but no other signs of bleeding. At physical examination, blood pressure is normal, no fever, no bone, thoracic or abdominal pain at palpation, no dyspnoea, no abnormalities on neurologic examination. However, there is an important weight loss (>10%) and an asthenia which could be associated with systemic vasculitis.

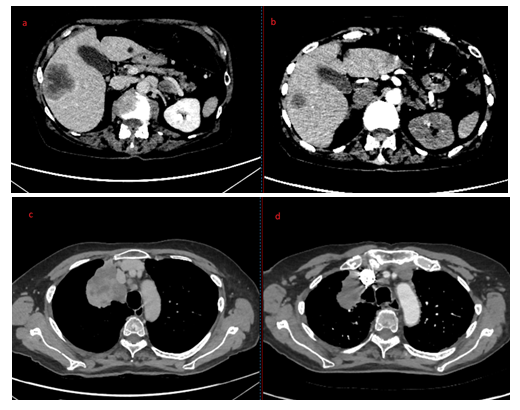

Laboratory tests revealed slight lymphocytopenia and thrombocytopenia. Renal and liver function were slightly disrupted as well as plasma ionogram. C-Reactive Protein was increased. The coagulation factors (fibrinogen, prothrombin, factor V, tissue thromboplastin) were normal except an increase of D-dimer (>12 000µg/L). (Table 1) Pulmonary embolism was excluded by normal CT pulmonary angiography. This examen revealed a good response to Osimertinib: from 60mm to 48mm for the lung mass, from 25mm to 14mm for the mediastinal lymph node, from 48mm to 23 mm for the hepatic metastasis, from 28mm to 16mm for adrenal metastasis, and no apparent bone lesion. No autoimmune disorders were found. Antinuclear antibody, antiphospholipid antibodies, cryoglobulin, proteinase-3, myeloperoxidase, antineutrophilic cytoplasmatic antibody were all negative. Serology tests (hepatitis B and C, herpes zoster, chicken pox, HIV, Epstein-Barr Virus) were also negative. IgA, IgM, IgG and C3 were not detected on direct immunofluorescence of skin biopsy. Osimertinib was discontinued and corticosteroids therapy was initiated (120mg/d for 6 days and 60mg/d) associated with cyclophosphamide (500mg every 2 weeks for 3 injections). After 8 days, the skin lesions regressed (Figure 2a and 2b) and after 33 days the skin lesions almost disappeared (Figure 3a and 3b).

Figure 1a and 1b: Hands (a) and face (b) skin lesions at the admission (19 days after Osimertinib initiation).

|

Abnormal parameters |

Normal Range |

Results |

|

Lymphocytes |

1070-3900 |

693/µL |

|

Platelets |

177-379 |

174 000/µL |

|

CRP |

0-5 |

69.6 mg/L |

|

Urea |

2.5-7.2 |

16.7 mmol/L |

|

Sodium |

136-145 |

133 mmol/L |

|

Potassium |

3.4-4.5 |

4.7 mmol/L |

|

GGT |

8-33 |

72 UI/I |

|

CPK |

29-68 |

15 U/I |

|

PT |

64-83 |

59g/L |

|

Albumin |

34-48 |

24.5g/L |

|

D-dimer |

<500 |

12 518 ng/mL |

Table 1: Laboratory tests.

Figure 2a and 2b: Hands (a) and face (b) skin lesions 8 days after Osimertinib discontinuation and immunosuppressive therapy initiation.

Figure 3a and 3b: Hands (a) and face (b) skin lesions 33 days after Osimertinib discontinuation and immunosuppressive therapy initiation.

3. Discussion

Osimertinib is a third-generation inhibitor of the intracellular tyrosine kinase domain of epidermal growth factor receptor, nowadays prescribed in first line treatment for lung carcinoma with EGFR mutation. The most common cutaneous AEs of Osimertinib, mostly grade 1-2, are rash or acne (58%), dry skin (36%) and paronychia (35%) [2]. Clinically, the cutaneous vasculitis also known as necrotizing vasculitis or leukocystoclastic vasculitis, is an unusual toxicity. EGFR-TKIs-induced cutaneous vasculitis can manifest as ecchymosis, petechia, and purpuric plaques. These lesions occurred in the first month of treatment [12]. To our knowledge, we report the second case of cutaneous vasculitis induced by Osimertinib [13], and the first one such early after treatment initiation. Nevertheless, few authors had already reported cutaneous vasculitis induced by first-generation EGFR-TKIs [14-17]. Most of cutaneous AEs induced by EGFR-TKIs can be attributed to the specific inhibition of EGFR but it is also possible that EGFR-TKIs exert a direct or indirect effect on the capillaries [18] or that these lesions originate from immunologic reactions induced by deposition of immunocomplexes [14]. In our case, the absence of IgA, IgM, IgG or C3 deposits in the vessel wall does not consolidate this hypothesis. The exact pathogenesis of cutaneous vasculitis induced by Osimertinib (or other generation of EGFR-TKIs) has not yet been clarified.

Treatment discontinuation and corticosteroids therapy have shown appropriate efficacy in the management of cutaneous vasculitis induced by EGFR-TKIs. On the advice of medical internist, we decided to add cyclophosphamide to corticosteroids in the management of our patient because of the severity of local (necrotic lesions) and general symptoms (weight loss, fatigue, high level of C-reactive protein). In absence of any high-quality data to guide management, more aggressive immunosuppressive drugs than corticosteroids could be considered [19]. As some studies suggest, cutaneous reactions may predict treatment efficacy. For the patient of this case report, the Osimertinib treatment duration was precisely 19 days. The CT pulmonary angiography carried out to exclude pulmonary embolism revealed a very good response to the treatment despite its short duration (Photo 4). Some international studies have found a correlation between clinically graded skin toxicity and patient-reported outcome, with longer PFS and OS. The development and the severity of skin lesion could be an important predictor for efficacy of EGFR-TKIs treatment [20-22]. While the results of the previous studies seem to correlate specifically skin rash with EGFR-TKIs efficacy (gefitinib or erlotinib), others skin toxicities could also be an efficient clinical marker for predicting the response of patients with NSCLC to EGFR-TKIs. In summary, cutaneous vasculitis is an uncommon complication of EGFR-TKIs. Grade 1-2 cutaneous vasculitis is reported in 0.3% of cases in the summary of product characteristics against 0% of cases for Grade 3. However, two cases have already been published. Clinicians need to be alert to this side effect for manage it effectively.

Figure 4a, 4b, 4c and 4d: Hepatic metastasis before (a) and after (b) Osimertinib treatment; Pulmonary mass before (c) and after (d) Osimertinib treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank all physicians who participate in data collection and we thank the patient for accepting the publication

Funding

None

References

- Ettinger DS, Aisner DL, Wood DE, et al. NCCN Guidelines Insights: Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer, Version 5.2018. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 16 (2018): 807-821.

- Soria JC, Ohe Y, Vansteenkiste J, et al. Osimertinib in Untreated EGFR-Mutated Advanced Non-Small-Cell Lung Cancer. N. Engl. J. Med 378 (2018): 113-125.

- Ramalingam SS, Vansteenkiste J, Planchard D, et al. Overall Survival with Osimertinib in Untreated, EGFR-Mutated Advanced NSCLC. N. Engl. J. Med 382 (2020): 41-50.

- Takeda M, Okamoto I, Nakagawa K. Pooled safety analysis of EGFR-TKI treatment for EGFR mutation positive non-small cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer 88 (2015): 74-79.

- Pastore S, Lulli D, Girolomoni G. Epidermal growth factor receptor signalling in keratinocyte biology: implications for skin toxicity of tyrosine kinase inhibitors. Arch Toxicol 88 (2014): 1189-203.

- Perez-Soler R. Rash as a surrogate marker for efficacy of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors in lung cancer. Clin Lung Cancer 8 (2006): S7-S14.

- Finlay MR, Anderton M, Ashton S, et al. Discovery of a potent and selective EGFR inhibitor (AZD9291) of both sensitizing and T790M resistance mutations that spares the wild type form of the receptor. J Med Chem 57 (2014): 8249-8267.

- Balagula Y, Garbe C, Myskowski PL, et al. Clinical presentation and management of dermatological toxicities of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. Int J Dermatol 50 (2011): 129-146.

- Hu JC, Sadeghi P, Pinter-Brown LC, et al. Cutaneous side effects of epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors: clinical presentation, pathogenesis, and management. J Am Acad Dermatol 56 (2007): 317-326.

- Reyes-Habito CM, Roh EK. Cutaneous reactions to chemotherapeutic drugsand targeted therapies for cancer Part II. Targeted therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol 71 (2014): 217.e1-217.

- Langford, C.A. Vasculitis.Journal of Allergy and ClinicalImmunology 111 (2003): S602-S612.

- Agero AL, Dusza SW, Benvenuto-Andrade C, et al. Dermatologic side effects associated with the epidermal growth factor receptor inhibitors. J Am Acad Dermatol 55 (2006): 657-670.

- Hamada K, Oishi K, Okita T, et al. Cutaneous Vasculitis Induced by Osimertinib. J Thorac Oncol 14 (2019): 2188-2189.

- Fernandez-Guarino M, Ryan AM, Perez-Garcia B, et al. Necrotizing vasculitis due to gefitinib (Iressa). Int J Dermatol 46 (2007): 890-891.

- Ko JH, Shih YC, Hui RC, et al. Necrotizing vasculitis triggered by gefitinib: an unusual clinical presentation. J Clin Oncol 29 (2011): e169-e170.

- Boeck S, Wollenberg A, Heinemann V. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis during treatment with the oral EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib. Ann Oncol 18 (2007): 1582-1583.

- Su BA, Shen ST, Chang LY, et al. Successful rechallenge with reduced dose of erlotinib in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma who developed erlotinib-associated leukocytoclastic vasculitis: a case report. Oncol Lett 3 (2012): 1280-1282.

- Kurokawa I, Endo K, Hirabayashi M. Purpuric drug eruption possibly due to gefinitib (Iressa). Int J Dermatol 44 (2005): 167-168.

- Chen KR, Carlson JA. Clinical approach to cutaneous vasculitis. Am J Clin Dermatol 9 (2008): 71-92.

- Ciardiello F, Tortora G. EGFR antagonists in cancer treatment. N Engl J Med 358 (2008): 1160-1174.

- Liu HB, Wu Y, Lv TF, et al. Skin rash could predict the response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitor and the prognosis for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 8 (2013): e55128.

- Wacker B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J, et al. Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studies. Clin Cancer Res 13 (2007): 3913-3921.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 75.63%

Acceptance Rate: 75.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks