Liver Transplantation in Childhood-Disputable Indications for Retransplantation in the Adulthood

Marek Mamos1, Julia Hirchy-?ak1, Hanna Wi?niewska1, Patryk Modelewski1, Aleksandra Waszczyk1, Mi?osz Parczewski2, Marta Wawrzynowicz-Syczewska1*

1 Department of Infectious Diseases, Hepatology and Liver Transplantation, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland

2 Department of Infectious Diseases, Tropical and Acquired Immunodeficiency, Pomeranian Medical University, Szczecin, Poland

*Corresponding Author: Marta Wawrzynowicz-Syczewska, Department of Infectious Diseases, Hepatology and Liver Transplantation, Pomeranian Medical University, 71-445 Szczecin, Poland

Received: 26 October 2025; Accepted: 05 November 2025; Published: 28 November 2025

Article Information

Citation:

Marek Mamos, Julia Hirchy-Żak, Hanna Wiśniewska, Patryk Modelewski, Aleksandra Waszczyk, Miłosz Parczewski, Marta Wawrzynowicz-Syczewska. Liver Transplantation in Childhood-Disputable Indications for Retransplantation in the Adulthood. Archives of Clinical and Medical Case Reports. 9 (2025): 234-241.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: A 25-year retrospective analysis of pediatric liver transplantations after transition to the adulthood service was carried out with the special emphasis on patient’s survival, differences in survival related to age, gender, type of donation (deceased vs living), transplantation technique, type of biliary anastomosis and indications for retransplantation. A few controversial indications for retransplantation were discussed in more detail.

Material and methods: A group of 39 pediatric recipients were analyzed using current data and data provided by the national transplant registry. Survival was censored at 25 years of observation. Kaplan-Meyer cumulative mortality was calculated; statistical significance of survival was analysed using log-rank test.

Results: The probability of 25-year survival in the study group was 75%. A course without complications was recorded only in 12.8% of recipients. Neither sex, age at transplant, type of transplantation technique, type of biliary anastomosis nor the type of donation (deceased vs. living) influenced survival. Retransplantation was considered in 30% of pediatric recipients and performed in 12.8% of them.

Conclusions: Major indication for retransplantation was recurrent sclerosing cholangitis. Transplants were refused by noncompliant recipients who developed chronic rejection and graft loss. Vascular complications such as diffuse portal vein thrombosis make decisions for retransplantation the most difficult and controversial.

Keywords

<p>Pediatric liver transplantation; Living donor liver transplantation; Transition period; Noncompliance; portal vein thrombosis</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

Outcomes in pediatric liver transplants (PLT) are excellent and better than in adults. It is especially clear when historic overall mortality and graft survival is compared to the contemporary results, and these achievements were possible due to the development of surgical techniques and better immunosuppressive regimens [1]. According to the data from the largest pediatric liver transplant center in Pittsburgh, a 20-year overall survival reached 64.4% and the most significant factor affecting improvement was a change in basic immunosuppressive drug from cyclosporin to tacrolimus [2]. However, in the last several years the results did not improve significantly being hampered by the acute and chronic rejection, disease recurrence, kidney injury, infections and malignancies that are consequences of longer years lived and longer exposure to immunosuppressive medications. A center-specific 25-year retrospective analysis of pediatric liver transplant recipients transferred from childhood to the adulthood service was carried out with the special emphasis on patient’s survival, differences in survival related to age, gender, type of donation (deceased vs living), transplantation technique, type of biliary anastomosis and indications for retransplantation. A few controversial indications for retransplantation are discussed in more detail.

2. Materials and methods

A cross-sectional study was performed to evaluate pediatric liver transplant survivors who reached 18 years of age and transferred their care to the post-transplant center for adults. Altogether 39 pediatric LT recipients, transplanted in the Children Memorial Hospital in Warsaw, were admitted to our outpatient department since year 2000, when transplant program began in our hospital. Detailed information on PLT was obtained from the transplant registry provided by the Polish Transplant Coordinating Centre POLTRANSPLANT. A special attention was paid to the indications for retransplantation in adulthood with the particular emphasis on cases where these indications were controversial or debatable. Three such cases are presented in more detail. There were 24 males (61.5%) and 15 females (38.5%) in the analyzed group. The median age at LT was 96.4 months (4-218 months) with 16 children (41%) less than 6 years of age at transplant. The major indication for PLT was biliary atresia. Indications for liver transplantation are listed in Table 1.

Table 1: Basic characteristics of the study group, n=39.

|

Clinical characteristics |

Value |

|

Sex [n, %] |

|

|

Male |

24 (61.5) |

|

Female |

15 (38.5) |

|

Age at transplant [months, median and range] |

96.4 (4 – 218) |

|

Transplantation in younger recipients (< 6 years of age) [n, %] |

16 (41) |

|

Follow-up after transition [years, median and range] |

5.9 (0 – 25) |

|

Indications for transplantation [n, %] |

|

|

Biliary atresia |

19 (48.7) |

|

Acute liver failure |

6 (15.4) |

|

Autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis |

3 (7.7) |

|

Other (PFIC, hyperammonemia, viral cirrhosis, HCC) |

11 (28.2) |

|

Type of donation [n, %] |

|

|

DDLT |

26 (66.6) |

|

LDLT |

13 (34.4) |

|

Transplantation technique [n, %] |

|

|

Classic |

27 (69.2) |

|

Piggyback |

12 (30.8) |

|

Type of biliary anastomosis [n, %] |

|

|

End-to-end |

12 (30.8) |

|

hepaticojejunostomy |

27 (69.2) |

|

Overall survival [months, median and range] |

222.4 (16 – 378) |

Twenty-six patients (66.6%) received cadaveric graft and in 13 cases (33.3%) a living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) was performed. Split or reduced size adult livers were not used in the study group. In 27 (69.2%) cases LT was done classically whereas in 12 (30.8%) cases piggy-back techniques were performed. End-to-end bile duct anastomosis was performed in 12 recipients, and in 27 cases hepaticojejunostomy was done. All patients but three received tacrolimus as a basic immunosuppression. A number of acute cellular rejection (ACR) episodes during childhood were sought and a comparison of survival was calculated between those with 2 or less ACR and with more than two ACR episodes. Survival rate was compared between males and females, deceased donor recipients vs. living donor recipients, and between younger recipients (< 6 years of age) and older children.

2.1 Statistical analysis

Survival was calculated using initial timepoint defined as a date of OLTx. End of observation was defined as either death date, last recorded date of visit (cases lost to follow-up) or 28 February 2025 for the patients remaining under care (termination of data collection). Survival was censored at 25 years (300 months) of observation. Kaplan-Meyer cumulative mortality was calculated; statistical significance of survival data was analyzed using log-rank test. Cox proportional hazards models were used to assess the effect of analyzed parameter on the risk of death and to calculate the hazard ratios (HR). P-values of 0.05 were considered significant. Commercial software (Statistica 13.0 PL, Stat soft, Warsaw, Poland) was used for these statistical calculations.

3. Results

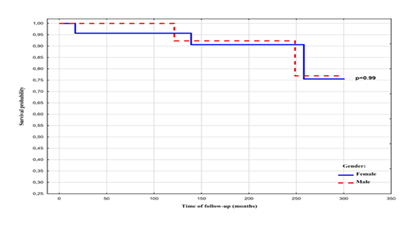

The median follow-up in the group of pediatric recipients in the outpatient department for adults was 5.9 years (0-25 years). Twenty patients (51.3%) from the study group are still under control and attend visits regularly. Six patients (15.4%) died and 13 (33.3%) are lost from follow-up, but according to the national registry they are still alive. Survival ranged from 16 to 378 months with the median survival of 222.4 months. Seven people stopped taking immunosuppressive medications among which 5 developed chronic rejection and liver insufficiency (4 patients died without retransplantation and 1 patient died after retransplantation again being non-compliant) and 2 patients developed operational immune tolerance. The “ideal” follow-up with no complications and comorbidities was noted only in 5 patients (12.8%). The probability of 25-year survival in the study group was 75%. There was no difference in survival for male and female patients at all time points (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Comparison of survival probability between males and females estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test.

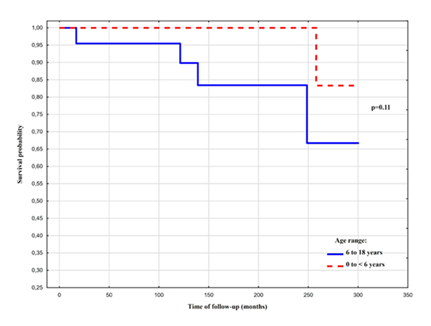

The survival of the recipients older than 6 years of age at transplantation did not differ significantly than those younger than 6 years of age (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Comparison of survival probability between younger and older recipients estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test.

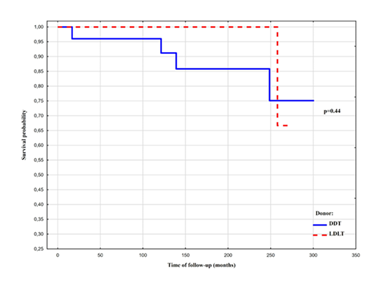

There was no difference in the overall survival between recipients of deceased grafts and living donor grafts (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Comparison of survival probability after deceased donor transplantation and living donor transplantation estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test

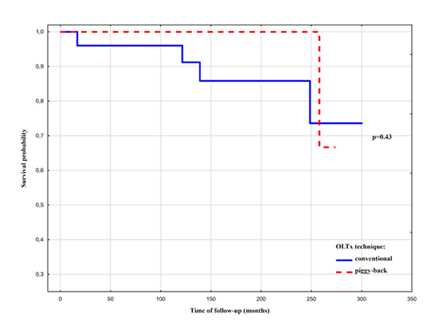

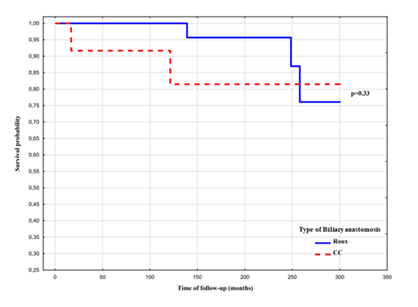

The surgical technique of transplantation (classical vs. piggyback) did not influence survival rate (Figure 4) neither the type of biliary anastomosis (duct-to-duct vs. hepaticojejunostomy) (Figure 5).

Figure 4: Comparison of survival probability after conventional vs. piggy-back transplantation estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test.

Figure 5: Comparison of survival probability in relations to the type of biliary anastomosis (Y-Roux vs. duct-to-duct) estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test.

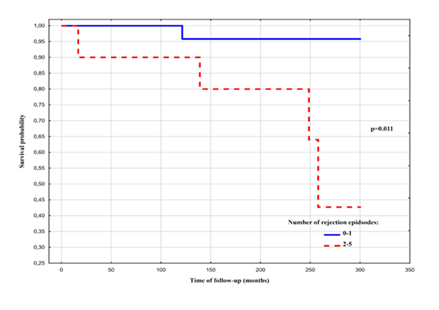

Survival rate was significantly lower in the recipients who experienced more than two episodes of the acute cellular rejection in childhood (Figure 6), HR: 8,86 (95% CI: 0,98- 80,08), p=0.05 (proportional hazard model).

Figure 6: Comparison of survival probability in relations to the number of rejection episodes (0-1 vs. 2-5) estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test

Similarly, survival was significantly worse in the emergency liver transplantation as compared to the elective surgery (Figure 7), HR: 9.05 (95% CI: 1.48-55.35), p=0.017 (proportional hazard model).

Figure 7: Comparison of survival probability after elective vs. urgent transplantation estimated by Kaplan-Meier analysis with log-rank test.

Retransplantation was considered in 12 patients (30.8%), and performed in 5, mostly due to recurrence of primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) with graft insufficiency. This data is shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Retransplantation in the study group, n=39.

|

Considered |

12 (30.8%) |

|

Performed |

5 (4 ASC, 1 chronic liver failure) (12.8%) |

|

Denied |

4 (10.2%) |

One retransplantation was offered to the non-compliant patient who delivered a baby and claimed not to take immunosuppressive medications to protect her child from the drug toxicity. A beneficial psychiatric consultation and seemingly good family support determined the decision about retransplantation that finally turned out to be wrong, and the patient eventually died due to immunosuppressive treatment termination and chronic rejection. Four retransplantations in non-compliant patients were refused due to poor cooperation with the patients and unfavorable psychiatric and psychological expertise. Four retransplantations due to PSC recurrence were successful in respect to good liver function, but two patients developed aggressive form of ulcer colitis in the post-transplant period requiring either biological treatment or colectomy. Four AIH/PSC patients are on the waitlist. In three cases retransplantation due to medical reasons is a controversial issue and sparks heated albeit inconclusive discussions in the transplant team. They are described below.

3.1 Case 1:

A female patient who requests for liver retransplantation, is currently at 25 years of age. She was transplanted due to biliary atresia when she was 7 years old. Transplantation was preceded by the Kasai portoenterostomy. It was a deceased donor transplantation with a classical technique. Hepaticojejunostomy was performed. The patient is fully compliant, attends visits regularly and always has had a good trough level of tacrolimus. The first episode of piercing abdominal pain took place at her 20 years of age. This pain is accompanied by the pain in chest, difficulty breathing, salivation and several watery, caustic stools. Attacks last several hours and end up with the debilitating pain and weakness in the lower limbs. After two days all symptoms are over and biochemical parameters fully normalize. During attacks parenchymal liver enzymes significantly increase (more than 10 times the upper limit of normal), always with AST predominance. There is no coagulopathy. Bilirubin and cholestatic parameters are usually within normal range; sometimes GGT increases twice or three times more than normal. She experiences several exhausting attacks per year. Intermittent porphyria was ruled out. Gastro- and colonoscopy did not show any abnormalities. Liver biopsy, performed two times two years apart soon after the attack, showed good liver architecture and normal appearance. MRCP picture was consistent with the stricture of hepaticojejunostomy, but it is debatable whether it is clinically significant taking into consideration that there are no signs and symptoms of cholestasis. Abdominal angiography showed no left hepatic artery branch and a significant disproportion of portal vein sizes between graft and recipient. The latter one was ballooned with no improvement in clinical condition. Provided these attacks are of ischemic nature, should the patient with fully functional liver be considered for retransplantation?

3.2 Case 2:

Another retransplantation is considered in the 22-year-old female, transplanted at her 4 months of age due to biliary atresia. It was a living donor liver transplantation (LDLT) of the left lateral segments of the liver. A piggy-back technique was used and hepaticojejunostomy was performed. The patient is on cyclosporin-based immunosuppression together with mycophenolate mofetil. She is fully compliant, attends visits regularly and always shows a good trough level of cyclosporin. As a child she experienced four episodes of the acute cellular rejection and CMV infection, treated successfully with valganciclovir. Since teenage years the patient shows massive and life-threatening bleedings from oesophageal varices and a small intestine. Portal vein thrombosis with cavernous remodeling was discovered. Liver biopsy showed proper liver structure and normal appearance. Fibrosis was excluded. Biochemical parameters are constantly within normal range with the exception of sideropenic anemia. Feasibility of retransplantation as well as indications are being discussed in case of otherwise healthy liver.

3.3 Case 3:

A third problematic pediatric recipient in which feasibility and indications for retransplantation are under debate is a 23-year-old female, transplanted at her 9 months of age due to biliary atresia. It was an LDLT with left lateral segments. Piggyback technique and hepaticojejunostomy were performed. As a child she experienced one episode of acute cellular rejection, successfully treated with steroid boluses. Since childhood she has kept on tacrolimus and a small dose of prednisolone. She is fully compliant, attends visits regularly and meets all recommendations. As a teenager she started to massively bleed from oesophageal varices and the small intestine. Portal vein thrombosis was discovered. Splenic artery embolization was performed with no improvement. She also had numerous argon therapy sessions due to bleeding episodes from stomach mucosa in the course of severe portal gastropathy. Liver function as well as liver enzymes are normal. Liver biopsy showed no fibrosis. In the computed angiography portal vein was not found. Superior mesenteric veins as well as splenic veins are obstructed. The portal flow to the liver takes place through a network of varices surrounding hepaticojejunostomy and the visceral surface of the graft. Arterial inflow through hepatic artery is normal. Interventional radiologists disqualified the patient from TIPSS procedure as impossible to perform. Feasibility as well as indications for retransplantation are heavily disputed similarly to the previous case.

4. Conclusion

Pediatric liver transplantation is no doubt a success story. Improvement in surgical techniques, better perioperative care and immunosuppression regimes have resulted in excellent long-term young recipient survival. Pediatric transplantation, however, brings a challenge of long-term patient outcomes including disease recurrence, development of surgical complications and psychosocial problems, therefore healthy recipients with no problems and comorbidities are in the vast minority. One of the risk factors for inferior results in PLT is adolescent non-adherence and difficulties in maintaining medications intake. The transition from childhood to adolescence is considered a particularly vulnerable time for young organ recipients resulting in disturbance of compliance. Rates of nonadherence among pediatric transplant recipients are as high as 50 to 65% and it places these patients at increased risk of graft loss [3,4]. Similar situations are observed in kidney recipients. About 35% of young adults lose a successfully functioning kidney transplant with 3 years of transfer from pediatric service to adult service [5]. Adolescence is a time of increasing independence, experimental attempts and rebellious behaviors influenced by peer groups rather than parents and physicians. Sudden transition from the safe and well-known environment into the large, busy and anonymous place for adults is a moment of considerable distress and anxiety. Better results are obtained when pediatric transplant centers are combined with the adult transplant service [6]. In our small series seven patients stopped taking immunosuppressive drugs and five of them lost their grafts. Thirteen patients gave up on specialist care or left the country without informing care providers about such decisions. Retransplantation offer for non-compliant recipients is a controversial issue.

Besides biopsychosocial problems, adolescents start to have long-term medical complications of transplantation performed in childhood. Complications following PLT can be divided into those related to the transplant itself and surgical issues, adverse events of immunosuppression, and the patient's overall health. These include episodes of rejection, infections (like CMV and EBV), development of malignancies (especially post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders), cardiovascular issues, renal impairment, and metabolic problems such as diabetes and hyperlipidemia. Additionally, complications like biliary strictures and portal vein thrombosis can occur. In our series only 5 (12.8%) patients do not show any health-related disturbances and have good quality life. Similar data were presented elsewhere [7]. The most important medical complications other than chronic graft rejection in non-compliant patients, observed in our study group, were the recurrence of AIH/PSC (also known as autoimmune sclerosing cholangitis, ASC) in four recipients and portal vein thrombosis (PVT). The latter one is observed in two LDLT patients. PTV remains a critical complication and poses a technical problem very often precluding successful retransplantation. The incidence of PVT varies from 2 to 10% in pediatric LDLT and ranges from 4% nowadays to 33% in older series in pediatric deceased donor LT [8]. PVT is classified according to Yerdel’s grading system [9] into four categories, where grade 1 means minimal or partial occlusion of PV with the lumen thrombosed in less than 50% and grade 4 means complete obstruction of PV together with proximal and distal superior mesenteric vein (SMV). In the setting of LDLT it is more difficult to obtain the appropriate vein grafts as compared to DDLT and PV reconstruction in case of thrombosis is especially problematic. In the abovementioned cases PVT can be classified as at least grade 3 with the complete occlusion of the PV lumen and partial or complete obstruction of SMV. In the past total PV thrombosis was considered an absolute contraindication for LT due to insufficient portal blood flow to the graft after anastomosis. One of the surgical treatment suggestions in our cases is combined liver-gut transplantation and the other proposal is a small intestine resection with the total parenteral nutrition to the end of the patient’s life. Both are quite challenging, broadly discussed with the other transplant teams, and the decision has not yet been made.

References

- Cuenca AG, Yeh H. Improving patient outcomes following pediatric liver transplant: current perspectives. Transplant Research and Risk management 11 (2019): 69-78.

- Jain A, Mazariegos G, Kashyap R, et al. Pediatric liver transplantation: a single center experience spanning 20 years. Transplantation 73 (2002): 941-947.

- Berquist RK, Berquist WE, Esquivel CO, et al. Adolescent non-adherence: prevalence and consequences in liver transplant recipients. Pediatr Transplant 10 (2006): 304-310.

- Fredericks EM. Nonadherence and the transition to adulthood. Liver Transpl 15 (2009): S63-9.

- Harden PN, Walsh G, Bandler N, et al. Bridging the gap: an integrated pediatric to adult clinical service for young adults with kidney failure. BMJ 344 (2012): e3718.

- Hung Y, Williams JE, Bababekov YJ, et al. Surgeon crossover between pediatric and adult centers is associated with decreased rate of loss to follow-up among adolescent renal transplantation recipients. Pediatr Transplant (2019).

- Lund LK, Grabhorn EF, Ruther D, et al. Long-term outcome of pediatric liver transplant recipients who have reached adulthood: a single-center experience. Transplantation 107 (2023): 1756-1763.

- Nacoti M, Rugeri GM, Colombo G, et al. Thrombosis prophylaxis in pediatric liver transplantation: a systemic review. World J Hepatol 10 (2018): 752-760.

- Yerdel MA, Gunson B, Mirza D et al. Portal vein thrombosis in adults undergoing liver transplantation: risk factors, screening, management, and outcome. Transplantation 69 (2000): 18-73.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 75.63%

Acceptance Rate: 75.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks