The Role of Immunohistochemistry in the Distinction of Invasive Plasmacytoid Urothelial Carcinoma from its Histologic Mimics

McKenney JK2, Sangoi AR3, Gokden N1*

1University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, Little Rock, AR, USA

2Department of Pathology, Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland, OH, USA

3El Camino Hospital, Mountain View, CA, USA

*Corresponding Author: Neriman Gokden, Department of Pathology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, 4301 West Markham slot # 517, Little Rock, AR 72205, USA.

Received: 27 February 2023; Accepted: 16 April 2023; Published: 26 April 2023

Article Information

Citation: McKenney JK, Sangoi AR, Gokden N. The Role of Immunohistochemistry in the Distinction of Invasive Plasmacytoid Urothelial Carcinoma from its Histologic Mimics. Archives of Clinical and Medical Case Reports. 7 (2023): 155-161.

View / Download Pdf Share at FacebookAbstract

Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma is a rare and aggressive variant of bladder cancer that is characterized by infiltrating neoplastic cells that closely resemble plasma cells. It may mimic plasmacytoma, lymphoma, and carcinomas such as lobular carcinoma of breast and poorly differentiated carcinomas of gastrointestinal tract secondarily involving the bladder. There is limited data regarding the comparative immunophenotypes of these morphologically similar tumors. The surgical pathology and consultation files at three institutions were searched for plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma, lobular breast carcinoma and diffuse or signet ring type gastrointestinal carcinoma from 1998 to 2010. H&E slides of 31 cases were reviewed to confirm diagnoses. A focused immunohistochemical panel including antibodies against E-Cadherin, P63, P53, CD138, MUM-1, estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), GCDFP-15, CA 125, cytokeratin 7 (CK 7), cytokeratin 20 (CK 20), S100p and GATA3 was performed. Percent immunoreactivity was scored semi-quantitatively. All plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas (n=11) showed immunoreactivity for CD138 and P53, but were negative for MUM-1, ER, PR, and GCDFP-15. E-Cadherin was completely lost in 25% of cases, and nuclear P63 was lost in 55% of cases. 99% had CK7 expression while 73% expressed CK20. GATA3 was expressed in 73% and S100p was expressed in 64% of cases. Lobular breast carcinomas (n=10) were immunoreactive for ER (100%), PR (60%), GCDFP-15 (90%), CK 7 (100%), P53 (60%), CD 138 (100%), CA 125 (20%), GATA3 (100%), S100p (40%), but were negative for MUM-1, P63, E-cad, and CK 20 in all cases. Diffuse/signet ring type gastrointestinal carcinomas (n=10) were immunoreactive for CD138 and E-cad, but negative for ER, PR and GCDFP-15 in all cases. Other variably positive markers in diffuse/signet ring type gastrointestinal carcinoma included P53 (90%), P63 (30%), CA125 (10%), CK 7 (60%), and CK 20 (80%), GATA3 (10%), S100p (50%). In summary, this study shows that the typical immunoprofile of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma is CD138 (+), CK7/20 (+), GATA3 (+), S100p (+) and MUM-1 (-), ER/PR/GCDFP-15 (-). The absence of MUM-1 staining in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma would be helpful in the distinction from plasma cells and lymphocytes. Diffuse/signet ring type gastrointestinal carcinoma has a variable immunoprofile which overlaps significantly with plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma. P63 and E-cad expression in a subset of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma and negative ER, PR and GCDFP-15 stains may be useful in the distinction from lobular breast carcinoma.

Keywords

<p>Carcinoma; Immunohistochemistry; Plasmacytoid; Plasmacytoma; Urothelial Carcinoma</p>

Article Details

1. Introduction

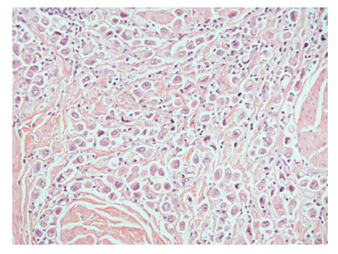

Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma is a rare variant of urothelial carcinoma that has acquired increasing importance since it may have prognostic and possibly therapeutic consequences for patients. The prognosis is uniformly poor with most patients having advanced stage of disease at presentation and metastatic disease [1-3]. Two different groups described plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma in 1991. The first case report was described by Sahin et al in 1991 in a patient presenting with multiple lytic bony metastases of the ribs and skull leading to a misdiagnosis of multiple myeloma on initial aspiration biopsy. A subsequent bladder biopsy confirmed a plasmacytoid carcinoma of urothelial origin [4]. The same year, Zuckerberg et al published a case series of 5 patients with plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma simulating malignant lymphoma [5]. Since its first description 20 years ago, there have been approximately 30 published manuscripts, most of them in the form of case reports [6-19] and small case series [20-30]. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma may be pure or admixed with other patterns of urothelial carcinoma. It is characterized by tumor cells closely resembling plasma cells forming sheets or single cells infiltrating the bladder wall in a mostly acellular or myxoid stroma (Figure 1A). The tumor cells are often discohesive and may closely mimic plasmacytoma, lymphomas, metastatic lobular carcinoma of the breast and/or metastatic poorly differentiated carcinomas from the gastrointestinal tract with diffuse/signet ring type histology. In some cases, plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma may even mimic a non-neoplastic inflammatory infiltrate. The examination of the surface urothelium for in situ carcinoma and/or high grade urothelial carcinoma is helpful for determining urothelial origin when present. The distinction of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma from its histologic mimics is particularly problematic in small biopsies; however, there is limited data on comparative immunophenotypes of these morphologically similar tumors.

Figure 1: Discohesive plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma cells infiltrating between muscularis propria muscle bundles in bladder.

2. Materials and Methods

The surgical pathology and consultation files at three institutions were searched for plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma, lobular breast carcinoma and diffuse or signet ring type gastrointestinal carcinoma from 1998 to 2010. All hematoxyline and eosin-stained sections of the 31 cases were reviewed by 2 investigators (N.G, J.K.M) and diagnoses for all cases were confirmed. A focused IHC panel using antibodies against E-Cadherin, P63, P53, CD138, MUM-1 (multiple myeloma oncogene 1), estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15), CA 125, cytokeratin 7 (CK 7), cytokeratin 20 (CK 20), S100p and GATA3 was performed on 4-micron thick formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded sections mounted on charged slides and baked at 60C for 20 minutes. Positive and negative control slides were run in parallel with all cases. Antibody sources and dilutions for the study are listed in Table 1. The following patterns of immunolabeling were noted as positive- MUM-1, P53, P63, ER, PR: nuclear; CD138, E-Cad, GCDFP-15, CA-125, CK7, CK20, S100P, GATA-3: membranous and/or cytoplasmic. Percent immunoreactivity in the neoplastic cells was semi quantitatively graded from 0 to 4+ (0: negative; 1+: 1-25%; 2+: 26-50%; 3+: 51-75%; 4+: 76-100%) and results for each group are listed in Table 2.

|

Antigen |

Clone |

Dilution |

Antigen retrieval |

Source |

|

MUM-1 |

MRQ-43 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

P53 |

Bp-53-11 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

CD138 |

B-A38 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

P63 |

BC4A4 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Biocare (Concord, CA) |

|

E-Cad |

36-M |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

ER |

SP1 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

PR |

1E2 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

GCDFP-15 |

EP1582Y |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

CA125 |

OC125 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

CK7 |

SP52 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

CK20 |

SP33 |

Prediluted |

EDTA HIER |

Ventana (Tuscan, AZ) |

|

S100P |

16/S100P |

1:25 |

Leica Bond Citrate |

BD Biosciences (San Diego, CA) |

|

GATA-3 |

HG3-35 |

1:10 |

Leica Bond EDTA HIER |

Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA) |

Table 1: Antibody sources and dilutions.

|

MUM-1 |

P53 |

CD138 |

P63 |

E-cad |

ER |

PR |

GCDFP15 |

CA125 |

CK 7 |

CK 20 |

S100p |

GATA3 |

|

|

PUC |

|||||||||||||

|

1 |

neg |

4+ |

3+ |

neg |

2+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

2+ |

4+ |

4+ |

neg |

3+ |

|

2 |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

neg |

3+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

3+ |

2+ |

|

3 |

neg |

4+ |

3+ |

neg |

2+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

1+ |

3+ |

neg |

3+ |

neg |

|

4 |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

neg |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

3+ |

3+ |

|

5 |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

2+ |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

2+ |

3+ |

|

6 |

neg |

1+ |

3+ |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

1+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

|

7 |

neg |

2+ |

4+ |

3+ |

3+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

|

8 |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

1+ |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

1+ |

2+ |

1+ |

2+ |

|

9 |

neg |

1+ |

3+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

2+ |

neg |

2+ |

|

10 |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

3+ |

3+ |

2+ |

|

11 |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

4+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

2+ |

4+ |

1+ |

1+ |

1+ |

|

PCDG15 |

|||||||||||||

|

1 |

neg |

3+ |

4+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

1+ |

3+ |

neg |

|

2 |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

1+ |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

|

3 |

neg |

2+ |

4+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

2+ |

2+ |

neg |

|

4 |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

2+ |

neg |

|

5 |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

|

6 |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

1+ |

neg |

|

7 |

neg |

4+ |

3+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

|

8 |

neg |

4+ |

1+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

|

9 |

neg |

4+ |

2+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

|

10 |

neg |

4+ |

1+ |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

1+ |

2+ |

|

LCB |

|||||||||||||

|

1 |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

neg |

4+ |

2+ |

4+ |

neg |

2+ |

3+ |

|

2 |

neg |

neg |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

1+ |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

|

3 |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

3+ |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

|

4 |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

2+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

|

5 |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

2+ |

3+ |

|

6 |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

neg |

2+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

2+ |

3+ |

|

7 |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

3+ |

3+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

|

8 |

neg |

1+ |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

3+ |

4+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

2+ |

3+ |

|

9 |

neg |

1+ |

1+ |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

4+ |

4+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

|

10 |

neg |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

3+ |

1+ |

neg |

4+ |

neg |

neg |

3+ |

Table 2: The semi quantitative scoring results of antibodies for each group. PUC: Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma, PDCGIS: Poorly differentiated carcinoma of gastrointestinal system, LCB: Lobular carcinoma of breast.

3. Results

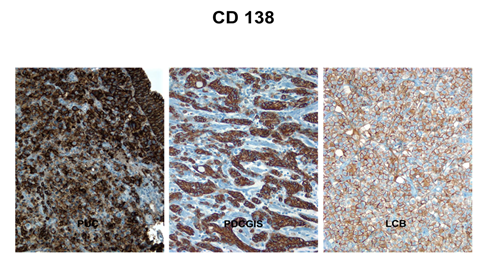

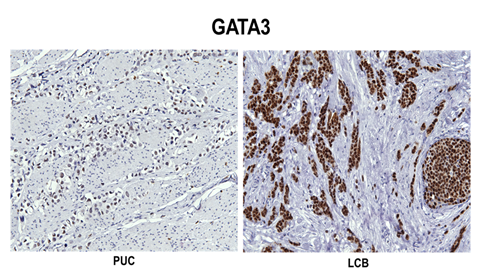

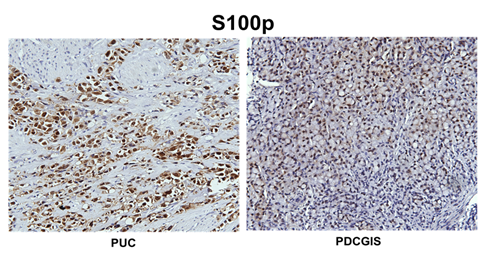

The percent positivity for each antibody in three groups is summarized in Table 3. CD138 and P53 showed the highest sensitivity for all plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas (n=11, 100%) (Figure 2A). CK 7, CK 20 and E-cad showed slightly less sensitivity for plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas (n=11) were negative for MUM-1, ER, PR, and GCDFP-15 in all cases. The majority of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas (75%) showed focal E-Cadherin expression (1+ to 3+) while it was completely lost in 25% of cases, and nuclear P63 was only expressed in 45% of cases. Ninety-nine % had CK7 expression while 73% expressed CK20. Seventy three percent had immunoreactivity with GATA3 (Figure 3A), while 64% of cases were labeled with S100p (Figure 4A). Lobular carcinomas of breast (n=10) were immunoreactive for ER (100%), PR (60%), GCDFP-15 (90%), CK 7 (100%), P53 (60%), CD 138 (100%, Figure 2C), CA 125 (20%), GATA3 (100%), S100p (40%), but negative for MUM-1, P63, E-cad, and CK 20 in all cases. Poorly differentiated carcinomas of gastrointestinal tract with a diffuse/signet ring morphology (n=10) were immunoreactive for CD138 and E-cad, but negative for ER, PR and GCDFP-15 in all cases. Other variably positive markers included P53 (90%), P63 (30%), CEA125 (10%), CK 7 (60%), and CK 20 (80%), GATA3 (10%), S100p (50%, Figure 4B).

Figure 2: CD138 is diffusely positive in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma (A) in diffuse or signet ring type gastric carcinoma (B) and in lobular breast carcinoma (C).

Figure 3: Diffuse nuclear GATA3 positivity in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma (A) and lobular breast carcinoma (B).

Figure 4: Diffuse staining with S100p in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma (A) and in diffuse or signet ring type gastric carcinoma (B).

Table 3: Immunohistochemical staining results for plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma (PUC), lobular breast carcinoma and diffuse/signet ring type carcinoma of gastrointestinal tract (D/SCGIT) (% cases positive).

4. Discussion

The plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma is one of the unusual variant patterns of urothelial carcinoma and its incidence is reported to be 1% in one large series [29-31]. It has been associated with poor outcomes when compared with pure urothelial cancer. It is usually diagnosed at an advanced pathologic stage with unfavorable clinical outcome despite multimodal therapy [1-3]. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma may have potential for an unusual pattern of disease spread similar to lobular breast carcinoma and diffuse/signet ring type carcinomas of gastrointestinal tract. We have published a series of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma with discontinuous intraperitoneal involvement and carcinomatous effusions warranting a careful intra-abdominal staging evaluation of the peritoneal surface, bowel wall, and omentum at the time of surgery [19]. The histologic distinction of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma from morphologically similar tumors in the urinary bladder and metastatic sites can be a major diagnostic problem, particularly in small biopsy samples. The histologic overlap with plasmacytoma, reactive plasma cells, lymphoma, lobular breast cancer, and signet ring carcinoma is considerable. In difficult cases, immunohistochemistry may be utilized to aid in these distinctions. Several studies have evaluated the immunoprofile of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma. A compounding factor in the immunophenotype of these tumors is that the majority of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma cases express CD138, a marker for plasma cell differentiation. In routine practice, it is crucial to get cytokeratin stain with CD138 in the context of the differential diagnosis of a carcinoma. The range of CD138 positivity is reported from 27% to 100% in series of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas published to date [17, 20, 21, 26, 28, 32]. MUM-1 has never been reported positive in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma [17, 28]. Our cases with 100% CD138 labeling and negative MUM-1 are keeping with the existing literature. The absence of MUM-1 staining and cytokeratin labeling in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma would be helpful in the distinction from multiple myeloma and chronic inflammation. There is only one paper on ER/PR/GCDFP-15 expression in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas. In their series by Borhan et al., plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas lacked expression of ER but PR was seen in 13.3% and GCDFP-15 was present in 24.4% of cases. GATA 3 was staining in 82.2% of their cases while uroplakin II was completely negative [40]. All plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma cases in our series showed no staining in tumor cells with ER/PR and GCDFP-15. Given the published lack of uroplakin staining breast carcinomas, a panel of stains should include uroplakin II to exclude metastatic lobular breast carcinoma to the bladder. The majority of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma cases express CK7 and CK20. In published series, CK 7 expression ranges from 70% to 100% while CK20 expression ranges from 31% to 100% [20, 21, 25, 28, 32, 33]. Our results (CK 7: 99% sensitivity, CK20: 73% sensitivity) are keeping with the existing literature. The urothelial-lineage-associated markers such as S100p and GATA3 have rarely been comprehensively evaluated in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma. S100p has been shown to mediate tumor growth, metastasis and invasion in multiple tumors including pancreas, colorectal, stomach, and breast carcinomas [34-38]. Liu et al reported 86% sensitivity for S100p in bladder carcinomas [37] while Higgins et al detected high levels of S100p and GATA3 protein expression in urothelial carcinomas and both antibodies helped to distinguish urothelial carcinomas from other genitourinary neoplasms in their study [38]. Only study specifically looked for S100p and GATA3 staining in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas is in an abstract form by Ananaiah et al, and their 11 cases showed staining with GATA3 and S100p in all cases (100%) [32]. In our group, the sensitivity of GATA3 and S100p is relatively lower 73% and 64%, respectively. The specificity of GATA3 for plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma is much lower in our series. Ten cases of lobular breast carcinoma showed extensive staining with GATA3 (100%) while S100p was marking only 50% of cases. Our 10 cases of poorly differentiated gastrointestinal system carcinomas exhibited 10% positivity with GATA3 and 50% positivity with S100p (2 pancreatic adenocarcinomas, 2 colorectal adenocarcinomas, 1 gastric adenocarcinoma).While GATA3 may help when we need to make differential diagnosis between plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma and diffuse/signet ring type carcinomas of gastrointestinal tract but it may not help to distinguish plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma from lobular breast carcinoma. Additionally S100p has a low specificity for plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma in our cases. Therefore it is less helpful to distinguish plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma from lobular breast carcinoma and diffuse/signet ring type carcinoma of gastrointestinal tract. The other markers supportive of urothelial differentiation, p63 and 34BE-12 has only been investigated in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas by Paner et al [32]. Our cases have similar sensitivity with p63 (45%) when compared to 50% in their study. We also stained our cases with p53 and found 100% sensitivity for plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas which is consistent with the published series [28]. However, lobular breast carcinomas (60%) and diffuse/signet ring type carcinoma of gastrointestinal tract (90%) exhibited high levels of P53 expression as well in our series. CA125 has not been previously studied in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinomas and 45% our cases showed positive staining with CA125. It is less likely to be helpful in the distinction because 20% of lobular carcinoma of breast and 10% of diffuse/signet ring type carcinoma of gastrointestinal tract were positive with CA125 in our series. The loss of E-cadherin expression has been reported to be a possible marker for plasmacytoid and signet ring cell differentiation in urothelial carcinomas and it can explain their discohesive pattern of growth and aggressive behavior [17,25,39]. No E-cad expression is seen in all cases in several series [25,26,32,33,39,40,41] but study by Keck et al [17] had 13% and another by Perrino et al. [18] showed 43% of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma cases exhibited E-cad in their study group. In our series 25% of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma cases lost E-cad expression while 75% showed focal positivity (1+ to 3+). In this study, the typical immunoprofile of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma is CD138 (+), CK7/20 (+), GATA3 (+), S100p (+), and MUM-1(-), ER/PR/GCDFP-15 (-). The absence of MUM-1 staining in plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma would be helpful in the distinction from plasma cells and lymphocytes. For the distinction of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma and lobular breast cancer, p63, CK20 and E-cad had lower sensitivity (45%, 73%, and 75%, respectively), but were highly specific for plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma. In addition, ER and GCDFP-15 had both high sensitivity and specificity for lobular breast carcinoma (100% and 90%), respectively. P63 and E-cad expression in a subset of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma and ER, PR and GCDFP-15 negativity is useful in distinction from lobular breast carcinoma. In our series, plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma has a variable immunoprofile that overlaps significantly with diffuse/signet ring type gastrointestinal carcinoma. None of the tested markers were 100% specific in the distinction between plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma from diffuse/signet ring type gastrointestinal carcinoma. Urothelial-lineage marker GATA3 should be used with caution in the distinction because 10% of gastrointestinal cancers expressed GATA3 in our study. In summary, for any given tumor that creates diagnostic difficulty in the distinction between plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma and potential histologic mimics, it is important to carefully choose an immunopanel with consideration of the many expected immunophenotypic overlaps and to render a diagnosis only after close clinical and imaging correlation.

References

- Soylu, A, Aydin NE, Yilmaz U, et al. Urothelial carcinoma featuring lipid cell and plasmacytoid morphology with poor prognostic outcome. Urology 65 (2005): 797.

- Kawashima A, Ujike T, Nin M, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a case report. Nihon Hinyokika Gakkai Zasshi 100 (2009): 590-594.

- Keck B, Giedl J, Kunath F, et al. Clinical course of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the upper urinary tract: A case report. Urol Int 89 (2012): 120-122.

- Sahin, AA, Myhre M, Ro JY, et al. Plasmacytoid transitional cell carcinoma. Report of a case with initial presentation mimicking multiple myeloma. Acta Cytol 35 (1991): 277-280.

- Zuckerberg LR, Harris NL, Young RH. Carcinomas of the urinary bladder simulating malignant lymphoma. A report of five cases. Am J Surg Pathol 15 (1991): 569-576.

- Kohno T, Kitamura M, Akai H, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Int J Urol 13 (2006): 485-486.

- Philippou P, Kariotis I, Volanis D, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a rare malignancy. Urol Int 86 (2011): 370-372.

- Tanaka A, Ohori M, Hashimoto T, et al. A case of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: rapid progression after transurethral resection. Hinyokika Kiyo 58 (2012): 101-103.

- Sakuma T, Maurin C, Ujike T, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder with prostate cancer: report of two cases. Prog Urol 21 (2011): 891-894.

- Keck B, Stoehr R, Wach S, et al. Plasmacytoid and micropapillary urothelial carcinoma: rare forms of urothelial carcinoma. Urologe A 50 (2011): 217-220.

- Demirovic A, Marusic Z, Lenicek T, et al. CD138-positive plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of urinary bladder with focal micropapillary features. Tumori 96 (2010): 358-360.

- Aldousari S, Sircar K, Kassouf W. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a case report. Cases J 28 (2009): 6647.

- Shimada K, Nakamura M, Ishida E, et al. Urothelial carcinoma with plasmacytoid variants producing both human chorionic gonadotropin and carbohydrate antigen 19-9. Urology 68 (2006): 891.e7-10.

- Mitsogiannis IC, Ioannou MG, Sinani CD, et al. Plasmacytoid transitional cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Urology 66 (2005): 194.

- Rahman K, Menon S, Patil A, et al. A rare case of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of bladder: diagnostic dilemmas and clinical implications. Indian J Urol 27 (2011): 144-146.

- Molek KR, Seili-Bekafigo I, Stemberger C, et al. Diagn Cytopathol 30 (2012): 1002.

- Keck B, Stoehr R, Wach S, et al. The plasmacytoid carcinoma of the bladder-rare variant of aggressive urothelial carcinoma. Int. J Cancer 129 (2011): 346-354.

- Perino Carmen M, Eble J, Kao C, et al. Plasmacytoid/diffuse urothelial carcinoma: a single-institution immunohistochemical and molecular study of 69 patients. Hum Pathol 90 (2019): 27-36.

- Ricardo-Gonzalez RR, Nguyen M, Gokden N, et al. Plasmacytoid carcinoma of the urinary bladder: A urothelial carcinoma variant with predilection for intraperitoneal spread. J of Urol 187 (2012): 852-855.

- Nigwekar P, Tamboli P, Amin MB, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma: detailed analysis of morphology with clinicopathologic correlation in 17 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 33 (2009): 417-24.

- Lopez-beltran A, requena MJ, Montironi R, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder. Hum Pathol 40 (2009): 1023-1028.

- Ro JY, Shen SS, Lee HI, et al. Plasmacytoid transitional cell carcinoma of urinary bladder: a clinicopathologic study of 9 cases. Am J Surg Pathol 32 (2008): 752-757.

- Gaafar A, Garmenda M, de Miquel E, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. A study of 7 cases. Actas Urol Esp 32 (2008): 806-810.

- Mai KT, Park PC, Yazdi HM, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: report of seven new cases. Eur Urol 50 (2006): 1111-1114.

- Fritsche HM, Burger M, Denzinger S, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: histological and clinical features of 5 cases. J Urol 180 (2008): 1923-1927.

- Keck B, Stohr R, Goebell PJ, et al. Plasmacytoid carcinoma. Five case reports of a rare variant of urothelial carcinoma. Pathologie 29 (2008): 379-382.

- Perez-Montiel D, Wakely PE, Hes O, et al. High grade urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis: clinicopathologic study of 108 cases with emphasis on unusual morphologic variants. Mod Pathol 19 (2006): 494-503.

- Raspollini MR, Sardi I, Giunti L, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder: clinicopathologic, immunohistochemical, ultrastructural, and molecular analysis of a case series. Hum Pathol 42 (2011): 1149-1158.

- Shah RB, Montgomery JS, Montie JE, et al. Variant (divergent) histologic differentiation in urothelial carcinoma is under-recognized in community practice: impact of mandatory central pathology review at a large referral hospital. Urol Oncol 31 (2013): 1650-1655.

- Chalasani V, Chin JL, Izawa JI. Histologic variants of urothelial cancer and nonurothelial histology in bladder cancer. Can Urol Assoc J 3 (2009): S193-8.

- Nigwekar P, Amin MB. The many faces of urothelial carcinoma. An update with an emphasis on recently described variants. Adv Anat Pathol 15 (2008): 218-233.

- Paner GP, Annaiah C, Gulmann C, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of novel and traditional markers associated with urothelial differentiation in a spectrum of variants of urothelial carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Human Pathol 45 (2014): 1473-1482.

- Sato K, Veda Y, Kawamura K, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a case report and immunohistochemical study. Pathol Res Pract 205 (2009): 189-194.

- Jiang H, Hu H, Tong X, et al. Calcium-binding protein S100P and cancer: mechanisms and clinical relevance. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 138 (2012): 1-9.

- Liu H, Shi J, Anandan V, et al. Reevaluation and identification of the best immunohistochemical panel (pVHL, maspin, S100p, IMP-3) for ductal adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Arch Pathol Lab Med 136 (2012): 601-609.

- Wang Q, Zhang YN, Lin GL, et al. S100P, a potential novel prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Oncol Rep 28 (2012): 303-310.

- Liu H, Shi J, Wilkerson ML, et al. Immunohistochemical evaluation of GATA3 expression in tumors and normal tissues: a useful immunomarker for breast and urothelial carcinomas. Am J Clin Pathol 138 (2012): 57-64.

- Higgins JP, Kaygusuz G, Wang L, et al. Placental S100 (S100p) and GATA3: markers for transitional epithelium and urothelial carcinoma discovered by complementary DNA microarray. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007; 31(2007): 673-680.

- Lim MG, Adsay NV, Grignon DJ, et al. E-cadherin expression in plasmacytoid, signet ring cell and micropapillary variants of urothelial carcinoma: comparison with usual-type high grade urothelial carcinoma. Mod Pathol 24 (2011): 241-247.

- Wang Z, Lu T, Du L, et al. Plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma of the bladder: a clinical pathological study and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 5 (2012): 60-68.

- Borhan WM, Cimino-Mathews AM, Montgomery EA, et al. Immunohistochemical differentiation of plasmacytoid urothelial carcinoma from secondary carcinoma involvement of the bladder. Am J Surg Pathol 41 (2017): 1570-1575.

Impact Factor: * 5.3

Impact Factor: * 5.3 Acceptance Rate: 75.63%

Acceptance Rate: 75.63%  Time to first decision: 10.4 days

Time to first decision: 10.4 days  Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks

Time from article received to acceptance: 2-3 weeks